Abstract

Previous work in our laboratory has shown that food deprivation and food presentation produce different patterns of neuronal activity (as measured by c-Fos immunoreactivity) in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of rats. Since the amygdala has been implicated in both motivational and reinforcement processes and has neuronal connections to both the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens, it was of interest to assess amygdaloid c-Fos immunoreactivity during similar manipulations of food deprivation and presentation. In the current study, c-Fos counts in both basolateral and central amygdalar nuclei were observed to increase in rats 12 and 36-h food deprived (relative to 0-h controls) – an effect reversed by the presentation of either a small or large meal (2.5 or 20g of food). In another experiment, rats working on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement exhibited elevated break-points as a function of food deprivation, a result consistent with the view that the feeding manipulations increased the subjects’ level of motivation. In contrast, food deprivation reduced the spontaneous locomotor activity of rats, presumably as a result of an inherent energy-conservation strategy when no food is readily available. These data suggest that the state of food deprivation is associated with: a.) enhanced behavioral output only when food is attainable (increased goal-directed behavior, but decreased spontaneous activity), and b.) increased synaptic engagement in neuronal circuits involved in affective valuation and related decision-making (increased c-Fos counts in the amygdala).

Keywords: basolateral amygdala, central amygdala, behavioral economics, food motivation, food reinforcement

Introduction

Motivational states exert a profound effect on decision-making and the execution of behavioral strategies. Defined as any state that energizes and directs behavior, motivation highlights a particular goal amongst the alternatives available at a given moment, and prompts the organism to dynamically adjust its behavior in the service of that goal [13, 14]. Of particular interest are motivational states resulting from a physiological deficit, such as dwindling reserves of energy or nutrients, as these represent a universal problem for animals and are therefore important factors in decision-making.

The mammalian forebrain contains a distributed network of structures that subserves the behavioral and decision-making functions to which motivational states are relevant. This circuitry includes the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and amygdala [19, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 46, 47]. Previous work in our laboratory suggests that mPFC tracks changes in motivational state (operationalized as period of food deprivation), while NAcc responds to the presentation of a reinforcing food stimulus, though in a fashion modulated by motivational state [28]. The current study explores the role of the amygdala, as it projects to both mPFC and NAcc [2, 3, 20, 21] and functions to asses the affective/motivational valence of stimuli [9, 32, 41], thus guiding the organism’s decision to output effort [19]. In order to examine the amygdala’s response to the motivational state caused by food deprivation, three experiments were devised utilizing manipulations of hunger and feeding. Using c-Fos immunoreactivity as a marker of synaptic engagement [28, 40], two amygdalar subregions, the basolateral (BLA) and central nuclei (CeA), were assessed after either 0, 12, or 36-h of food deprivation alone, after these three deprivation periods followed by a small meal, or after the same periods of deprivation followed by unrestricted feeding.

The above-mentioned structures govern the complex calculations involved in decision making and the organization of behavior, and, as they are differentially responsive to food deprivation, are capable of using motivational state as a factor in the generation of behavioral strategies. To relate our neurological findings in the mPFC, NAcc and amygdala to decision making processes known to be affected by these very brain areas, two experiments were designed to examine the effects of motivational state on behavioral output in two different contexts. One assessed the effect of varying periods of food deprivation (0, 12, or 36-h) on spontaneous locomotion, and the other examined the influence of the same deprivation periods on operant performance on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Although other research has tested food-deprived rats in similar behavioral assays [5, 22, 37], the authors are aware of no other reports in which the acute periods of food deprivation employed here (0, 12, and 36-h) were systematically tested in two contexts: one in which no food was available, and one in which the animal was allowed to exert effort for the return of differing magnitudes of food reinforcer. Thus, these experiments will allow us to assess the impact that the presence or absence of reinforcement has on the behavior of a motivated animal.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects were 102 male Sprague-Dawley rats obtained from Charles Rivers Laboratories (Hollister, CA) weighing between 310 and 350 grams at the beginning of each experiment. Animals were gentled through daily handling on each of 5 days prior to the initiation of testing. The rats were individually housed in hanging plastic tubs located in the Psychology Department vivarium in a temperature controlled room (22°C) maintained on a 12:12 light-dark cycle (lights on at 0700h). Subjects had ad libitum access to food prior to food deprivation and ad libitum access to water in their home cages throughout the experiment. All procedures were executed in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were reviewed and approved by the UCSB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

Locomotor Activity Chambers

Locomotor activity was measured in 12 identical Plexiglas chambers (20cm W × 40cm L × 20cm H; Kinder Scientific, San Diego). Each enclosure was equipped with 15 infrared emitter-detector pairs evenly spaced along its long axis and 7 along its narrow axis; each located 8cm from the floor of the chamber. Beam breaks were used to chart locomotor activity in two dimensions and were recorded by a desktop computer running custom software (Kinder Scientific).

Operant Chambers

Lever press training and progressive ratio testing occurred in 8 standard operant conditioning chambers (29 cm W × 25 cm L × 30 cm H; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Each chamber was equipped with one non-retractable (inactive) and one retractable (active) lever, both positioned 7.0cm above the floor of the chamber. Between the two levers and situated 2.0cm above the floor was a pellet trough connected to a food dispenser located on the chamber’s exterior. Each chamber was equipped with a 2.8 W house light. Equipment control and data collection were achieved via a desktop computer running Med Associates software (MED-PC for Windows).

Locomotor Activity

The effects of three periods of prior food deprivation (either 0, 12, or 36-h) on locomotor activity and c-Fos immunoreactivity were assessed in animals given no food, a small meal (2.5g of sweetened 45mg pellets; BioServ, Frenchtown, NJ), or enough food to allow for unrestricted feeding (20g of the same pellets). Separate groups of animals were used for each experiment (3 deprivation conditions, 8 animals per condition -- thus, n=24 subjects per experiment). Prior to the initiation of food deprivation and 48h before locomotor testing, all subjects were allowed to habituate to the locomotor activity chambers for 1-h. Animals were then assigned to one of the three food deprivation conditions and food was removed from the home cages at the appropriate period of time prior to testing. At 0900h on test day, all subjects were placed in the locomotor chambers after 0, 11, or 35-h of food deprivation (depending on condition) and one hour of locomotor data were collected (baseline). At the end of this period either no food, 2.5 or 20g of food pellets were administered directly into the locomotor chambers by the experimenter, after which another hour of locomotor activity data were collected (test). At the end of this period, animals were sacrificed (see Perfusion below). Any leftover food was collected and weighed by the experimenter.

Perfusion and c-Fos Immunocytochemistry

As described previously [10, 29], animals were removed from the locomotor chambers, deeply anesthetized (intraperitoneal injection of 40 to 50 mg of sodium pentobarbital), and then transcardially perfused with 60 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 120 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Sections of 40 µm of brain tissue were cut on a Leica CM1800 cryostat and immediately mounted on 1.5% gelatin-coated slides. The amygdala (2.12 mm posterior to Bregma; Fig 1) was identified using the Paxinos and Watson [29] atlas as a guide. Sections mounted on slides were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 0.05M, pH 7.6 at room temperature) between the different treatments and stained using the ABC method. Sections were treated with 0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma #X-100 St. Louis, MO) and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma D-5879); incubated for 1 h in 20% normal goat serum (NGS; Sigma G6767)+1% bovine serum albumin (BSA-Fract V; Fisher Scientific, Los-Angeles, CA, BP1605-100) to block nonspecific binding, and then incubated for 24 h in the c-Fos primary antibody—1:1000 c-Fos (polyclonal rabbit anti-c-Fos Santa-Cruz Biotech, Santa-Cruz, CA)+0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma X-100)+1% NGS (Sigma G6767). Sections were incubated for 1 h in the secondary antibody Anti Rabbit IgG (Elite-Anti Rabbit Vector Kit, Vector labs PK6101, Burlingame, CA), and for 30 min in the avidin–biotin–horseradish-peroxidase complex (Elite-Anti Rabbit Vector Kit, Vector labs PK6101). Staining was visualized using the chromogen DAB (Sigma D-5637)+0.01% H2O2 (Fisher H325-500). Sections then were dehydrated and coverslipped. To control for variation in the immunohistochemical reaction, tissue from the different treatment groups was reacted together.

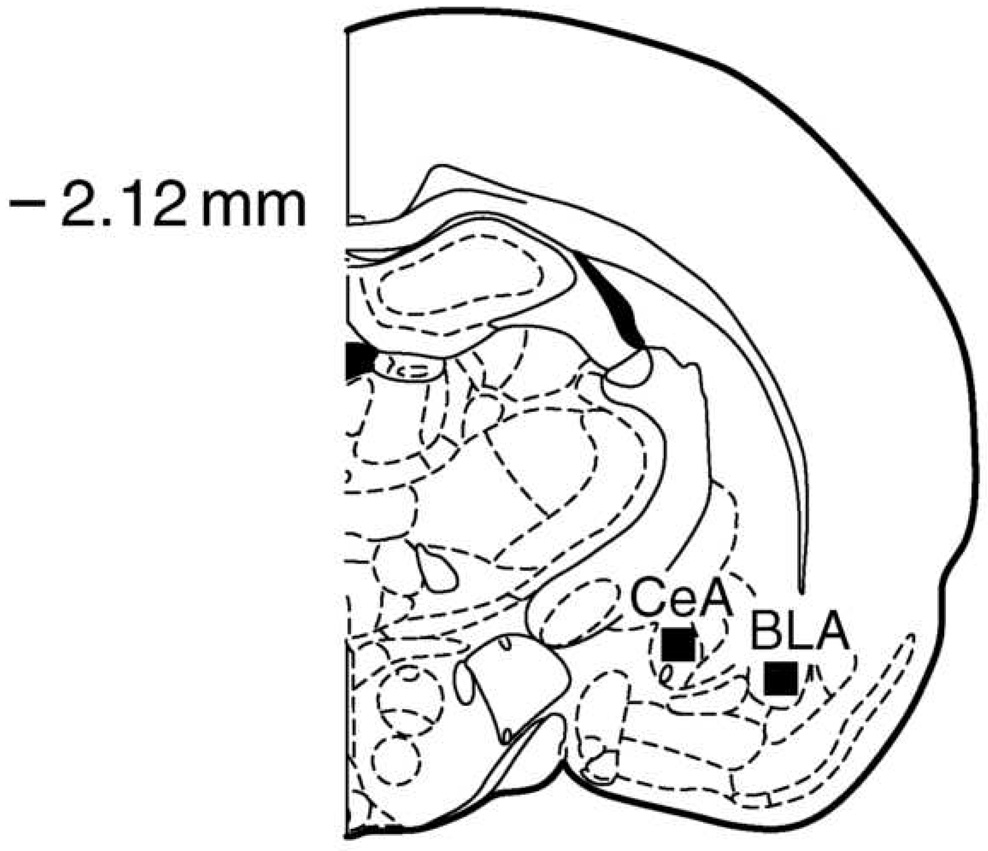

Figure 1.

Representation of the basolateral (BLA) and central (CeA) amygdalar nuclei from which c-Fos counts were obtained. −2.12 represents the millimeters posterior to Bregma. Redrawn from Paxinos and Watson [29].

c-Fos Counts

c-Fos-positive cell counts were recorded by visual inspection under 40× magnification of the histological slides. Cells were counted from two adjacent sections for each rat and restricted to twice an area defined by a 0.25×0.25-mm grid. Counts were made by two trained raters, both of whom were blind to the experimental condition of the subjects. The mean counts for the two raters were used for data analysis.

Progressive Ratio Procedure

Three additional groups of rats (n=10/group) were used to examine the effects of the above periods of food deprivation (0, 12, or 36-h) on operant responding under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement. For operant conditioning, all animals were placed on a restricted diet that reduced their body weight to 85% of free feeding levels. Then, during daily one-hour sessions, subjects were trained to lever press for 45mg food pellets on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement. Animals were considered to be performing to criterion when they earned >100 reinforcers over three consecutive training sessions. Once this occurred, the training phase of the experiment was ended and rats again received ad libitum access to food for at least 5 days, during which all animals regained their free-feeding weight. Subjects were then randomly assigned to one of the three deprivation conditions, and accordingly food was removed from the home cages at the appropriate point prior to testing, which was initiated at 0900h. After 0, 12, or 36-h of deprivation, subjects were placed in the operant chambers and allowed to lever press on a PR schedule of reinforcement. At the close of the session (the duration of which was determined by the animals, see below), subjects were returned immediately to the home cage and ad libitum access to food was restored. Animals were given a 72-h period to regain their pre-deprivation weight before another identical deprivation period was initiated in the same fashion, followed by a second PR test. Both PR sessions utilized the following formula to determine the ascending ratio requirements: 5e(reinforcer number * .20) −5, rounded to the nearest integer [36], which resulted in the following series of responses required to earn each successive reinforcement: 1, 2, 4, 9, 12 … 50, 62, 77, 95, 118 … etc. Animals had 30-mins to finish each individual response ratio and thereby earn food reinforcement; failure to complete a response ratio in the allotted 30-min ended the session. The number of ratios completed prior to session’s end was recorded as the subjects’ ‘break point’. The two sessions differed only in the magnitude of reinforcer for which animals were allowed to work. In one, subjects received a single 45mg sweetened pellet at the completion of each ratio, and in the other they received six of the same pellets. The order of the one and six pellet PR sessions was counterbalanced across subjects. Thus, we manipulated one between-subjects factor (food deprivation), with each subject undergoing two identical periods of either 0, 12, or 36-h of deprivation prior to each PR session, and one within-subjects factor (reinforcer magnitude), with all subjects receiving, in a counterbalanced order, a one and a six-pellet PR test.

Results

Amygdala c-Fos Immunoreactivity

Figure 2 depicts c-Fos counts in the basolateral amygdala (BLA; left panels) and central amygdala (CeA; right panels) after manipulations of food deprivation and feeding. Six separate one-way ANOVAs were performed, one corresponding to each of the six panels of the figure. For BLA (no meal condition), one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for Group [F(2,19)=6.40, p<.01] with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests revealing a significant difference between 12 and 0-h conditions (p<.05), 36 and 0-h conditions (p<.05), but not 12 and 36-h conditions. Thus, food deprivation elevated c-Fos immunoreactivity in the BLA.

Figure 2.

The effects of food deprivation on c-Fos immunoreactivity in the basolateral (left column) and central (right column) amygdalar nuclei. The top, middle, and bottom panels respectively depict the mean (+SEM) c-Fos counts in unfed animals, animals given a small (2.5g) meal, and animals given a large (20g) meal (i.e. unrestricted feeding); * indicates a significant difference compared to 0-h controls (p<.05).

For CeA (no meal condition), food deprived rats exhibited significantly elevated c-Fos levels at 36-h of deprivation relative to 0-h, but not at12-h of deprivation. Oneway ANOVA produced a significant main effect for Group [F(2,19)=5.28, p<.05] with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc comparisons confirming a significant difference only between animals in the 0 and 36-h deprivation groups (p<.05).

For subjects receiving either a small meal (2.5g sweetened pellets; Fig 2, panel B) or large meal (20g of the same pellets; Fig 2, panel C), separate one-way ANOVA’s revealed no differences in c-Fos immunoreactivity between the three deprivation groups. Thus, the BLA and CeA were responsive to food deprivation per se. However, once food was presented, those group differences in c-Fos counts were no longer present.

Locomotor Activity

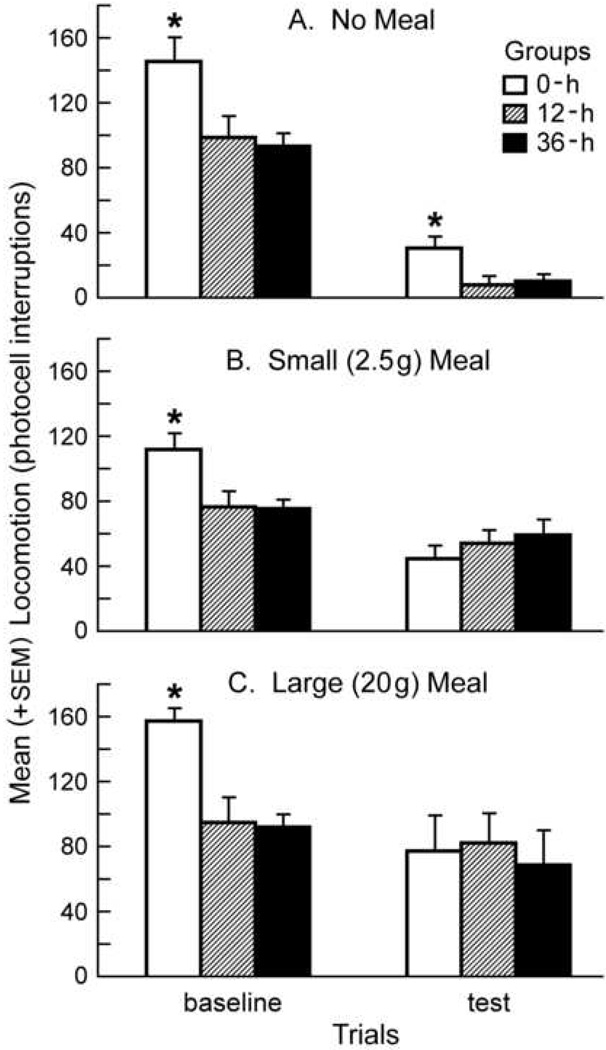

Figure 3 depicts locomotor data from the same subjects used to obtain the c-Fos data described above. Separate two-way mixed-design ANOVA’s were performed on the data depicted in each of the three of the panels, each with a between-subjects factor of Group (0, 12, or 36-h of food deprivation) and a within-subjects factor of Trial (pre-feeding baseline vs. post-feeding test hours).

Figure 3.

The effects of feeding on the mean (+SEM) locomotor activity of animals having different levels of food deprivation. The left column represents the pre-feeding hour (baseline) and the right column represents activity during a second hour (test) at the beginning of which animals were presented no food (panel A), a small meal (2.5g, panel B), or a large meal (20g, panel C). In each panel, * represents significant differences between 0-h deprived and both 12 and 36-h animals with baseline or test sessions.

For animals receiving no meal (Fig 3A), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for Group [F(2,21)=5.642, p<.05], as well as a significant main effect for Trial [F(1,21)=105.491, p<.01]. No significant Group × Trial interaction was found. Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests on Group data collapsed across Trial confirmed that subjects 0-h deprived produced significantly elevated locomotor counts relative to subjects from either the 12-h (p<.05) or 36-h (p<.05) deprivation groups. Thus, food deprivation produced an overall decrease in locomotion relative to non-deprived controls.

For animals receiving a small meal (Fig 3B), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant Group × Trial interaction [F(2,20)=7.288, p<.01], as well as a significant main effect for Trial [F(1,20)=36.031, p<.01]. No significant main effect for Group was found. Subsequent simple effects analysis performed on the baseline hour of the locomotor trial [F(2,20)=4.577, p<.05] revealed a significant difference between groups during this period. Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests confirmed that subjects from the 0-h deprivation group had significantly increased locomotor counts relative to subjects from both 12 and 36-h groups (p<.05 in both cases) during this hour of testing. Simple effects analysis performed on the test hour of the locomotor trial revealed no differences between groups during this period. Thus, prior to the presentation of a small meal, food deprived subjects were less active than non-deprived controls. Feeding produced statistically identical levels of locomotion between groups.

For animals receiving unrestricted feeding (Fig 3C), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant Group × Trial [F(2,21)=3.494, p<.05] interaction, as well as a significant main effect for Trial [F(1,21)=12.253, p<.01]. No significant main effect for Group was found. Simple effects analysis performed on the baseline hour of locomotor testing [F(2,21)=10.361, p<.01] revealed a significant difference between groups. Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests confirmed increased locomotion by animals from the 0-h group relative to those from the 12-h (p<.05) and 36-h (p<.05) deprivation groups. Simple effects analysis of the test hour of the locomotor trial revealed no significant group effects during this period. Thus, as in the small meal experiment, food deprived animals were less active during the baseline hour; unrestricted feeding produced similar locomotor counts in all groups.

Feeding

Leftover food from the small (2.5g) and large (20g) meal experiments was collected and weighed—this weight was subtracted from that of the total applied to each chamber to obtain amount consumed by each animal. No discernable leftovers were found in the small meal experiment. For the large meal experiment, one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect for group [F(2, 18)=20.985, p<0.001], and subsequent Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis confirmed a significant difference between animals 36-h deprived (mean ± S.E.M. consumed: 10.5 ± 0.51 g) and those 0-h (4.7 ± 1.0 g, p<.05) and 12-h deprived (5.7 ± 0.92g, p<.05).

Progressive Ratio

Figure 4 depicts the effects of manipulations of food deprivation and reinforcer magnitude on rats lever-pressing for food under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement. The data were tabulated in terms of break points (i.e., the number of ratios successfully completed prior to the end of the test session). A mixed design two-way ANOVA with a between-subjects factor of Group (0, 12, or 36-h of food deprivation) and a within-subjects factor of Reinforcer Magnitude (1 or 6 pellets) was computed on these data. This analysis revealed a significant main effects for both Reinforcer Magnitude [F(1,33)=5.124, p<.05], and for Group [F(2,33)=75.847, p<.01]. Subsequent Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests performed on the between-subjects measure of Group (period of prior deprivation) showed that rats from the 36-h deprived group produced higher break points than rats 0-h deprived (p<.01) and 12-h deprived (p<.05), and that rats 12-h deprived produced higher breakpoints than rats 0-h deprived (p<.01). A significant Group × Reinforcer Magnitude interaction was also obtained [F(2,33)=3.894, p<.05]. For repeated measures, correlated two-tailed T-tests confirmed that this interaction was driven by a significant difference between reinforcer magnitude only in the 12-h group (p<.05), where animals working for 6 pellets achieved higher break points than those working for 1 pellet. In summary, break points increase with the prior period of food deprivation; this was true for both 1 and 6-pellet conditions. Within deprivation conditions, increased reinforcer magnitude produced greater break points only in the 12-h group.

Figure 4.

Mean (+SEM) break points for food-deprived animals allowed to lever press on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Groups differed by level of food deprivation (0, 12, or 36-h) and each group was tested twice – once for reinforcement consisting of 1-pellet and once for 6-pellets. There was a statistically significant increase in break point as a function of level of food deprivation and reinforcer magnitude. Within groups, 6-pellets produced higher break points only in the 12-h case.

Discussion

The motivational state caused by both 12 and 36-h of food deprivation elevates c-Fos immunoreactivity in two amygdalar subregions, the basolateral (BLA) and central (CeA) nuclei. Presentation of either 2.5 or 20g of food produced comparable c-Fos counts in animals 0, 12 and 36-h deprived. Further, these same deprivation periods produced directionally opposite effects on spontaneous and goal-directed behavior, elevating break points in a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement (presumably reflecting an increase in motivational state) and reducing spontaneous locomotion (presumably as an energy-saving strategy in a non-food associated environment).

An organism’s assessment of the value or biological relevance of a goal-object is a critical element in decision-making and behavioral organization [7, 17, 34, 38, 39]. It has long been observed that food-reinforced behavior is energized by the motivational state associated with food deprivation [22]. A behavioral-economic conceptualization of valuation suggests that costs of effort, time, and energy incurred in the pursuit of a reinforcer are reflective of that reinforcer’s value to the organism [6, 18, 23]. Thus, hungrier animals emit more effort in the pursuit of food because they more highly value that food. The value or benefit with which an individual organism assesses an additional unit of a commodity (such as a given quantity of food and the caloric energy it yields) computed as the inverse of the amount of that commodity already consumed by the organism (i.e. energy balance, which diminishes with weight loss [11, 12]) is known as ‘marginal utility’ [26, 44, 45]. Thus, as caloric intake declines and energy balance decreases, the subjective value or utility of a given source of energy, like food, should increase. Conversely, food should seem less valuable to an animal with a more positive energy balance. The current results are interpreted within this conceptual framework.

We note that the current report utilized a high incentive sweetened pellet reinforcer, rather than standard lab chow, to ensure that our control (non-deprived) animals would consume the food. Though the sensory qualities of a sweetened food may boost its reinforcing efficacy, it is important to note that reliable differences between deprivation conditions were observed. Indeed, it is the amplitude of these differences that are most informative vis-à-vis the effects of motivational state on reinforcement process and their brain substrates.

A wide body of evidence, derived from across mammalian taxa, implicates dopamine terminal regions such as mPFC, NAcc and amygdala in the valuation of reinforcing stimuli [17, 24, 34, 38, 39, 42, 44]. If the marginal utility of a food reinforcer changes with food deprivation, then it stands to reason that these changes are instantiated in the neural substrates of valuation. The present report speaks to this point exactly. Both 12 and 36-h of food deprivation were sufficient to increase levels of synaptic engagement in amygdalar subregions BLA and CeA (though, for CeA, not to a statistically significant degree in the 12-h case). Thus, the activity of amygdala seems responsive to the state of food deprivation per se`, a pattern mirrored by results from pre- and infralimbic mPFC reported in our previous paper [29]. The finding that deprivation alone engages these regions is highly informative, as neural responsivity to the state of deprivation per se` represents a necessary first step in the assessment of the marginal utility of a food reinforcer.

Patterns of amygdalar c-Fos immunoreactivity changed when animals were presented with food. Both consumption of a small meal (2.5g sweetened pellets) and unrestricted feeding (20g of the same food) eliminated the between group differences in BLA and CeA c-Fos counts. That is, the amygdalar regions sampled were differentially responsive to the state of deprivation itself, while producing the same response to feeding, regardless of how large the meal or how long the prior period of deprivation. Hunger possesses an affective component that can be regarded as aversive [16]. As the stimulus (food) that ameliorates this affective state also reversed the relative increases in Fos counts observed in hungry animals, it seems reasonable to postulate that these regions responded to the negative/aversive aspects of food deprivation in the experiments reported here. This further suggests that consumption-related changes in deprivation-induced amygdalar activity may represent a substrate by which food, at least in part, functions as a negative reinforcer to hungry animals by altering aversion-related neuronal activity. This formulation is commensurate with the well established role of the amygdala in negative affect [1, 27].

Data presented in the current report, combined with those from a previous paper by us [29], suggest a multi-component neural system responsive to different elements of motivational state and reinforcer presentation. The amygdalar subnuclei sampled here, as well as the sub-compartments of mPFC reported on previously, are activated by food deprivation. After a small meal, mPFC was more active in animals 36-h deprived relative to animals from 0 and 12-h conditions, while BLA and CeA showed comparable levels of activity across deprivation conditions after consumption of either a small or large meal. These responses differed from those observed in NAcc, which were unaffected by manipulations of deprivation alone, but were engaged by presentation of a reinforcing food stimulus in a manner modulated by the duration of the prior deprivation period [29].

Thus, while amygdala and mPFC encode aspects of motivational state and changes therein, NAcc appears to respond primarily to the object towards which a given motivational state directs behavior, and in a fashion that reflects the magnitude of that motivational state. Together, these data, describing structures responsive to manipulations of food deprivation and reinforcer magnitude, suggest that this circuitry has the computational capacity to calculate changes in the value of a reinforcing stimulus as a function of current resources (‘marginal utility’). Given the responsivity of this system to relevant external stimuli [15, 25, 31, 35, 46], as well as its involvement in decision-making and the implementation of behavioral strategies [4, 8, 19, 42, 43], it seems further capable of translating an assessment of value into behavior. Though the exertion of effort can be guided by valuation, it is possible that the substrates determining value and the rigorous ouput of behavior are dissociable. Indeed, the assertion that information about value is passed to distinct brain centers tasked with motor control is in no way incommensurate with the ideas presented here.

To assay these concepts on a behavioral level, two experiments were conducted to assess the effect of motivational state on the output of goal-directed and spontaneous locomotion. Though previous assays using a comparable PR methodology have examined the effects of food restriction on food seeking [22], no previous study has systematically compared periods of food deprivation against variations in reinforcer magnitude in the manner of the current report. Food deprivation was found to boost the expression of motivated behavior in rats working for food on a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement. Though animals that underwent no food deprivation prior to PR testing still completed an average of 7(± 0.5) ratios in the pursuit of a sweetened pellet reinforcer, prior deprivation significantly elevated break points, or number of ratios successfully completed by session’s end. That is, animals 12-h deprived had higher break points than animals 0-h deprived, and animals 36-h deprived had higher break points than those 12-h deprived. As suggested above, an organism’s willingness to incur costs in the pursuit of a reinforcer is tied that organism’s assessment of its value. Thus, the willingness of food-deprived animals to proceed into higher ratios likely reflected a motivationally enhanced valuation of the reinforcer pursued (increased marginal utility).

Though the present interpretation comes from a behavioral economic and decision-making perspective, traditional views of motivational state suggest that it prompts a non-specific variety of behavioral activation [5, 37]. Put simply, motivational states are associated with elevated levels of arousal [37] and, as such, have been thought to produce a general increase in behavior relative to non-motivated animals. Thus, in keeping with this classical framework, one might predict that food deprivation would increase the output of spontaneous locomotion, as it did goal-directed behavior. However, it was found that while food-deprivation enhanced behavioral output in a PR paradigm, it decreased activity in the locomotor apparatus. It would seem that the capacity of motivational state to energize behavior is dependent on the type of behavior and the context in which it occurs. Indeed, in early reports on the activating effects of food deprivation on spontaneous locomotion the animals were tested in the same environment in which they were fed [5, 37]. In a small environment to which subjects had been previously habituated and which had no prior association with food, hungry animals reduced their overall level of activity presumably because these behaviors, which must necessarily come at some cost of energy, yielded nothing of value to the animal. Thus, while the motivational state related to food deprivation boosts the marginal utility of a food reinforcer, thus exciting the effortful output of behavior necessary to obtain it, it functions in a directionally opposite fashion when no reinforcer is available.

In summary, a behavioral-economic perspective seems commensurate with both our neurological and behavioral results. The neural substrates of valuation, all of which are responsive to cues external to the organism [15, 25, 31, 35, 46], were differentially engaged by manipulations of motivational state and subsequent presentation of a food reinforcer. Thus, it seems reasonable to conclude that these patterns of activity will interact differentially with information about the reinforcement structure of the immediate environment, producing contextually specific patterns of behavior. Marginal utility, which here refers to the enhanced value of food as a function of diminishing energy balance, therefore provides a unifying explanatory framework for the current results.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Laura Matthews and Gayane Demirchyan for their assistance in various aspects of experimental procedure. This work was supported by PHS grant DA-05041 awarded to AE.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Fear and the human amygdala. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5879–5891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn S, Phillips AG. Independent modulation of basal and feeding-evoked dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex by the central and basolateral amygdalar nuclei in the rat. Neurosci. 2003:295–305. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn S, Phillips AG. Modulation by central and basolateral amygdalar nuclei of dopaminergic correlates of feeding to satiety in rat nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10958–10965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10958.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albertin SV, Mulder AB, Tabuchi E, Zugaro MB, Wiener SI. Lesions of the medial shell of the nucleus accumbens impair rats in finding larger rewards, but spare reward-seeking behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2000;117(1–2):173–183. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartoshuk AK. Motivation. In: Kling JW, Riggs LA, editors. Experimental Psychology. New York: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, Inc.; p. 793. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum WM, Rachlin HC. Choice as time allocation. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969;12(6):861–874. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Lee GP. Different contributions of the human amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to decision-making. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5473–5481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05473.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H. Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. Brain. 2000;123:2189–2202. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belova MA, Paton JJ, Morrison SE, Salzman CD. Expectation modulates neural responses to pleasant and aversive stimuli in primate amygdala. Neuron. 2007;55:970–984. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Shahar O, Ahmed SH, Koob GF, Ettenberg A. The transition from controlled to compulsive drug use is associated with a loss of sensitization. Brain Res. 2004;995:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berthoud HR. Homeostatic and non-homeostatic pathways involved in the control of food intake and energy balance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(Suppl 5):197S–200S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berthoud HR, Morrison C. The brain, appetite, and obesity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:55–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bindra D. A unfied interpretation of emotion and motivation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1969;159:1071–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb12998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bindra D. A motivational view of learning, performance, and behavior modification. Psychol Rev. 1974;81:199–213. doi: 10.1037/h0036330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carelli RM. The nucleus accumbens and reward: neurophysiological investigations in behaving animals. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2002;1:281–296. doi: 10.1177/1534582302238338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson JN, Herrick KF, Baird JL, Glick SD. Selective enhancement of dopamine utilization in the rat prefrontal cortex by food deprivation. Brain Res. 1987;400:200–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen MX, Ranganath C. Behavioral and neural predictors of upcoming decisions. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2005;5:117–126. doi: 10.3758/cabn.5.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeGrandpre RJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Layng MP, Badger G. Unit price as a useful metric in analyzing effects of reinforcer magnitude. J Exp Anal Behav. 1993;60:641–666. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.60-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Floresco SB, Ghods-Sharifi S. Amygdala-prefrontal cortical circuitry regulates effort-based decision making. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:251–260. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Floresco SB, Blaha CD, Yang CR, Phillips AG. Dopamine D1 and NMDA reseptors mediate potentiation of basolateral amygdala-evoked firing of nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6370–6376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06370.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goto Y, O’Donnell P. Timing-dependent limbic-motor synaptic integration in the nucleus accumbens. PNAS. 2002;99:13189–13193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202303199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science. 1961;134:943–944. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev. 2008;115:186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kable JW, Glimcher PW. The neural correlates of subjective value during intertemporal choice. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1625–1633. doi: 10.1038/nn2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kargo WJ, Szatmary B, Nitz DA. Adaptation of prefrontal cortical firing patterns and their fidelity to changes in action-reward contingencies. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3548–3559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3604-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreps DM. A Course in Microeconomic Theory. Princeton, NJ: University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeDoux J. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neuorsci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan JI, Curran T. Stimulus-transcription coupling in the nervous system: involvement of the inducible proto-oncogenes fos and jun. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:421–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moscarello JM, Ben-Shahar O, Ettenberg A. Dynamic interaction between medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens as a function of both motivational state and reinforcer magnitude: a c-Fos immunocytochemistry study. Brain Res. 2007;1169:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2nd Edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters YM, O'Donnell P, Carelli RM. Prefrontal cortical cell firing during maintenance, extinction, and reinstatement of goal-directed behavior for natural reward. Synapse. 2005 May;56:74–83. doi: 10.1002/syn.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paton JJ, Belova MA, Morrison SE, Salzman CD. The primate amygdala represents the positive and negative value of visual stimuli during learning. Nature. 2006;439:865–870. doi: 10.1038/nature04490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips AG, Ahn S, Howland JG. Amygdalar control of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system: parallel pathways to motivated behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips PEM, Walton ME, Jhou TC. Calculating utility: preclinical evidene for cost-benefit analysis by mesolimbic dopamine. Psychopharm. 2006;191:483–495. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pratt WE, Mizumori SJY. Characteristics of basolateral amygdala neuronal firing on a spatial memory task involving differential reward. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:554–570. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.3.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richter CP. Animal behavior and internal drives. Quart Rev Bio. 1927;2:307–343. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salamone JD, Correa M. Motivational views of reinforcement: implications for understanding the behavioral functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine. Behav Brain Res. 2002;137:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar A, Mingote SM. Effort-related functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine and associated forebrain circuits. Psychopharm. 2007;191:461–482. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheng M, Greenberg ME. The regulation and function of c-fos and other immediate early genes in the nervous system. Neuron. 1990:477–485. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90106-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoenbaum G, Chiba AA, Gallagher M. Orbitofrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala encode expected outcomes during learning. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:155–159. doi: 10.1038/407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz W. Behavioral theories and the neurophysiology of reward. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:87–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sokolowski JD, Salamone JD. The role of accumbens dopamine in lever pressing and response allocation: effects of 6-OHDA injected into core and dorsomedial shell. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:557–566. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tobler PN, O'Doherty JP, Dolan RJ, Schultz W. Reward value coding distinct from risk attitude-related uncertainty coding in human reward systems. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1621–1632. doi: 10.1152/jn.00745.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Von Neumann J, Morgenstern O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton, NJ: University Press; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uwano T, Nishijo H, Ono T, Tamura R. Neuronal responsiveness to various sensory stimuli, and associative learning in the rat amygdala. Neuroscience. 1995;68:339–361. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wise RA. Dopamine, learning, and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:1–12. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]