Abstract

Development of the nervous system requires that timely withdrawal from the cell cycle be coupled with initiation of differentiation. Ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the N-Myc oncoprotein in neural stem/progenitor cells is thought to trigger the arrest of proliferation and begin differentiation. Here we report that the HECT-domain ubiquitin ligase Huwe1 ubiquitinates the N-Myc oncoprotein through Lys 48-mediated linkages and targets it for destruction by the proteasome. This process is physiologically implemented by embryonic stem (ES) cells differentiating along the neuronal lineage and in the mouse brain during development. Genetic and RNA interference-mediated inactivation of the Huwe1 gene impedes N-Myc degradation, prevents exit from the cell cycle by opposing the expression of Cdk inhibitors and blocks differentiation through persistent inhibition of early and late markers of neuronal differentiation. Silencing of N-myc in cells lacking Huwe1 restores neural differentiation of ES cells and rescues cell-cycle exit and differentiation of the mouse cortex, demonstrating that Huwe1 restrains proliferation and enables neuronal differentiation by mediating the degradation of N-Myc. These findings indicate that Huwe1 links destruction of N-Myc to the quiescent state that complements differentiation in the neural tissue.

N-Myc, a member of the Myc family of transcription factors that includes c-Myc and L-Myc, is normally expressed in the developing nervous system and other selected tissues1,2. Under normal conditions, N-Myc expression predominates in neural stem cells and neuroectodermal progenitors where c-Myc is undetectable1. Recent results from mice carrying targeted deletion of the N-myc gene in these cellular compartments established that N-myc expression in the developing nervous system is essential for the correct timing of cell-cycle exit and differentiation. In the absence of N-myc, precocious differentiation and premature withdrawal from the cell cycle of neural stem cells and cortical progenitors is associated with upregulation of Cdk inhibitors and reduced expression of the Myc target gene cyclin D2 (ref. 3).

One of the most important mechanisms by which N-Myc is regulated is at the level of protein stability, the turnover being accelerated by differentiation-promoting signals but significantly reduced in stem cells and cycling neural progenitors4–6. It has long been recognized that N-Myc is a short-lived protein targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation by the proteasome7–10. When linked through Lys 48 of ubiquitin, polyubiquitin chains function as signals for recognition by the proteasome that cleaves the ubiquitinated substrate. The accuracy of the system is conferred by the E3 ubiquitin ligase, which retains high specificity for the substrate11,12.

Here we identify the HECT-domain ubiquitin ligase Huwe1 as the destabilizing enzyme that targets N-Myc for proteasomal-mediated degradation in the neural tissue. This event is necessary for differentiation and cell-cycle withdrawal of stem cells and neural progenitors in vitro and in vivo.

RESULTS

Identification of Huwe1 as a partner of N-Myc in neural cells

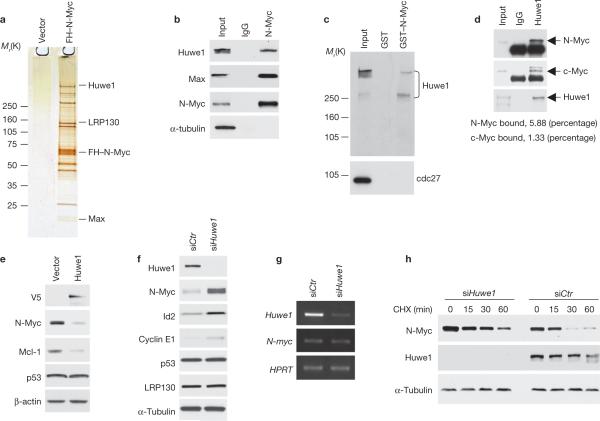

To identify the natural protein partners of N-Myc in neural cells, we expressed a Flag–HA epitope-tagged N-Myc (FH–N-Myc) in the human neuroblastoma cell line IMR32. We analysed proteins that co-purify with FH–N-Myc by LC/MS/MS after sequential Flag–HA immunoprecipitation and peptide elution13 and discovered that N-Myc complexes contain Huwe1 (Fig. 1a). Huwe1 (also known as Ureb1, Lasu1, Mule, ARF–BP1 or HECTH9) is a recently identified ubiquitin ligase, which belongs to the HECT (homologue of E6AP) family of E3 enzymes and is thought to target the ubiquitination and consequent degradation of Mcl1 and p53 (refs 14, 15). Huwe1 has also been reported to ligate c-Myc to a ubiquitin chain that may not target c-Myc for degradation by the proteasome16. N-Myc and Huwe1 interacted physically in independent immunoprecipitation experiments of Flag–N-Myc followed by western blotting for Huwe1, in which the protein was detected by two different affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1a and data not shown). We also showed that endogenous N-Myc binds to endogenous Huwe1 in IMR32 neuroblastoma cells (Fig. 1b). Using purified GST–N-Myc in a pull-down assay, we confirmed that N-Myc interacts specifically with Huwe1 in vitro (Fig. 1c). Next, we compared the affinity of the interaction between N-Myc or c-Myc and Huwe1. By quantitative analysis of Huwe1–N-Myc and Huwe1–c-Myc complexes in U2OS cells engineered to express exogenous N-Myc, we found that a 4-fold higher fraction of N-Myc than c-Myc was bound to Huwe1 in the cells (Fig. 1d). To determine whether Huwe1 affects the steady-state levels of N-Myc, we elevated or decreased Huwe1 in IMR32 and observed the effects, if any, on the accumulation of N-Myc. Expression of either full-length Huwe1 or an amino-terminal Huwe1 deletion mutant that retains the WWE, UBE and HECT domains (Huwe1–C) caused a marked reduction in the steady-state levels of endogenous N-Myc (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Information, Fig. S1b). However, expression of the N-terminal Huwe1 fragment (Huwe1–N), which lacks the key ubiquitin conjugation domain, did not decrease N-Myc (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1b). We also analysed whether, in neural cells, Huwe1 affects the accumulation of other putative substrates, namely p53, Mcl1 and c-Myc. Ectopic expression of Huwe1 reduced Mcl-1, an anti-apoptotic protein, but did not affect p53 (Fig. 1e), whereas c-Myc is not expressed either in the IMR32 neuroblastoma cells nor in neuroectodermal tissues1,2. RNA interference (siRNA)-mediated depletion of Huwe1 in IMR32 cells caused a marked accumulation of N-Myc and its targets Id2 (refs 17–20) and cyclin E1 (refs 21–23) without detectable changes in N-myc mRNA levels (Fig. 1f, g). Neither LRP130 protein (another N-Myc interactor) nor p53 were affected (Fig. 1f). Using cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, we determined the half-life of N-Myc after Huwe1 silencing. Compared with controls, cells treated with Huwe1 siRNA showed stabilization of the N-Myc protein half-life (Fig. 1h).

Figure 1.

Huwe1 binds N-Myc in vivo and controls N-Myc stability. (a) Identification of Huwe1 in N-Myc complexes from human neuroblastoma cells. Silver staining of affinity purified FH–N-Myc complexes from IMR32 cells. Specific N-Myc-interacting proteins were identified by mass spectrometry and are indicated. (b) Lysates from IMR32 cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-N-Myc antibody or normal mouse IgG (IgG). Western blotting was performed using anti-Huwe1, anti-Max and anti-N-Myc antibodies. α-tubulin is shown as a negative control for binding. Input is 1/100th of total extracts. (c) Lysates from IMR32 cells were mixed with GST or GST–N-Myc fusion proteins. Bound proteins were analysed by western blotting for Huwe1 or cdc27. Input is 1/50. Molecular markers are indicated on the left. (d) Lysates of U2OS cells stably expressing N-Myc were immunoprecipitated with antibodies directed against Huwe1 or rabbit IgG (IgG). Immunoprecipitates were resolved on SDS–PAGE and analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Input is 1/250. The percentage of cellular N-Myc and c-Myc associated with Huwe1 is indicated. (e) IMR32 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the V5-tagged full-length Huwe1 or the empty vector. The levels of endogenous N-Myc, p53 and Mcl-1 were examined by immunoblotting. The V5 antibody was used to detect exogenously expressed Huwe1. (f) IMR32 cells were transfected with control (siCTR) or Huwe1 (siHuwe1) siRNA. Lysates were analysed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. (g) Parallel samples were analysed for gene expression by semi-quantitative RT–PCR. (h) IMR32 cells were transfected with control (siCTR) or Huwe1 (siHuwe1) siRNA and treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times. α-tubulin is shown as a control for loading. Full scans of immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S9.

Huwe1 ubiquitinates N-Myc and primes it for proteasomal-mediated degradation

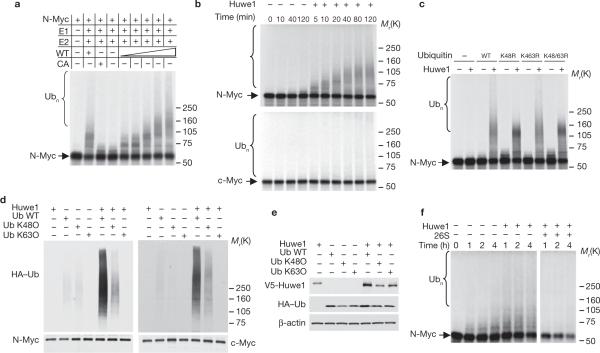

To determine whether Huwe1 is directly responsible for polyubiquitination of N-Myc, we purified a recombinant full-length Huwe1 protein produced from a baculovirus-based expression system (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1c). In the presence of E1, E2 (UbcH5) and an ATP-regenerating system, purified recombinant Huwe1 attached polyubiquitin chains to 35S-labelled, in vitro translated N-Myc in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 2a, b, top panel). Mutation of the critical Cys 4341 to Ala in the HECT domain of Huwe1 (Huwe1–CA) eliminated all ubiquitin ligase activity towards N-Myc (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, we found that although c-Myc is ubiquitinated by Huwe1 in this in vitro assay, the efficiency of ubiquitin chain-linkage on c-Myc by Huwe1 was noticeably lower than on N-Myc (Fig. 2b, lower panel). This finding indicates that N-Myc is a better substrate of Huwe1 than c-Myc. Next, we determined the mechanism by which Huwe1 links ubiquitin to N-Myc. We performed the in vitro ubiquitination reaction for N-Myc using purified Huwe1 and wild-type ubiquitin or ubiquitin molecules carrying point mutations in Lys 48 or Lys 63, two well established sites of isopeptide linkage (K48R, K63R, or K48R;K63R). When K48R ubiquitin was added to the in vitro reaction, the abundance of the slowest migrating bands decreased. This effect is due to capping of polyubiquitin chains by the mutant ubiquitin. In fact, K48R ubiquitin competes with the ubiquitin present in the wheatgerm lysate (used to translate N-Myc in vitro) and terminates the polyubiquitin chains. Although the K48R;K63R mutant produced the same effect, addition of K63R ubiquitin had no effect on the formation of polyubiquitin chains (Fig. 2c). Moreover, we compared the mechanism underlying ubiquitin linkage of N-Myc and c-Myc by Huwe1 in vivo. These assays were performed in U2OS cells expressing N-Myc and c-Myc. They demonstrated that ectopic expression of Huwe1 led to polyubiquitin linkage of either N-Myc or c-Myc through HA–ubiquitin wild-type and mutant in all Lys except Lys 48 (K48O) but not Lys 63 (K63O) (Fig. 2d, e). Together, these data indicate that the polyubiquitin chains attached by Huwe1 on N-Myc are linked through Lys 48, consistent with the recently established notion that HECT-domain ubiquitin ligases form homogeneous but not heterogeneous Lys chains24. In agreement with the role of Lys 48-linked ubiquitin chains as preferred recognition targets by the 26S proteasome25,26, we found that addition of purified 26S proteasome particles to the ubiquitination reaction mixture caused degradation of the polyubiquitinated N-Myc species (Fig. 2f).

Figure 2.

Huwe1 ubiquitinates and directs N-Myc degradation by the proteasome. (a) In vitro-translated, 35S-labelled N-Myc was incubated with increasing concentrations of wild-type Huwe1 (WT) or Huwe1–CA (CA) in the absence or presence of ubiquitin and the E2 protein UbcH5, as indicated, for 60 min at 37 °C. (b) In vitro-translated, 35S-labelled-N-Myc (upper panel) or c-Myc (lower panel) were incubated in the presence or in the absence of Huwe1 for the indicated times and the abundance of 35S-labelled Myc proteins was detected by fluorography. (c) Huwe1 catalyses the assembly of Lys 48-linked polyubiquitin chains on N-Myc in vitro. Ubiquitination of N-Myc by Huwe1 was carried out in the presence of either wild-type ubiquitin or the indicated ubiquitin mutants for 60 min at 37 °C. 35S-labelled N-Myc was detected by fluorography. (d) In vivo ubiquitination of Myc proteins by Huwe1. U2OS cells stably transfected with the retroviral expression plasmid pLZRS–N-Myc were cotransfected with empty vector or V5–Huwe1 and wild-type HA–ubiquitin (WT) or the mutants Lys 48 only (K48O) or Lys 63 only (K63O). After treatment with MG132 (5 μM) for 3 h, lysates were prepared in denaturing buffer and identical aliquots were immunoprecipitated with antibodies directed against N-Myc (left panel) or c-Myc (right panel). An anti-HA antibody was used to detect ubiquitin conjugates. Note that the efficiency of K48O-mediated ubiquitination is underestimated, compared with ubiquitination by WT ubiquitin, as a consequence of reduced expression of V5-Huwe1. (e) Total extracts from the experiment in d were analysed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody to detect ubiquitin monomers and an anti-V5 antibody to detect V5-tagged Huwe1 full-length. β-actin is a control for loading. (f) Ubiquitination of N-Myc by Huwe1 was carried out in the absence or presence of 26S proteasome particles, for the indicated times at 37 °C. 35S-labelled N-Myc was detected by fluorography of SDS–PAGE electrophoresed reactions. The bracket marks bands corresponding to polyubiquitinated N-Myc. Full scans of immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S9.

The Huwe1–N-Myc pathway controls neural differentiation of mouse ES cells

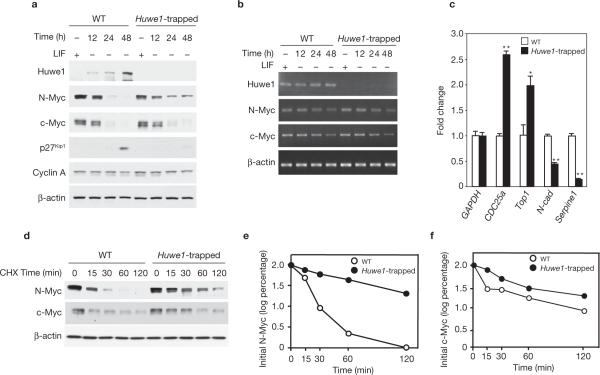

The expression of N-myc is highly enriched in mouse ES cells and must be downregulated to achieve neuronal differentiation and enable the post-mitotic state27–29. To determine whether Huwe1 is implicated in this process, we first used gene trapping for constitutive genetic inactivation of the Huwe1 locus in mouse ES cells. The RRE249 and HMA095 ES clones have been derived from the parental E14Tg2a.IV cells by insertion of the gene-trap vector containing β-geo into introns 4 and 74 of the Huwe1 gene, respectively (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2). Genomic PCR followed by DNA sequencing, as well as RT–PCR and western blot experiments from the two ES clones, confirmed that both insertions abolish the splicing of the Huwe1 exons that code for the essential HECT domain (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2b, c and data not shown). Functional analysis of the Huwe1–N-Myc pathway in RRE249 ES cells is shown in Figs 3–4; similar results have been obtained in the HMA095 clone. The leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) is essential for maintaining mouse ES cells in a self-renewing and undifferentiated state that closely resembles the pluripotent cells of the inner cell mass30. Following LIF withdrawal, ES cells rapidly lose their self-renewal and pluripotent capacity, undergo differentiation along multiple lineages, enter a quiescent state and eliminate N-Myc. Removal of LIF caused a clear increase in Huwe1 expression and elevation in the level of the Cdk inhibitor p27Kip1, a cell-cycle regulator whose expression in neural progenitors requires collapse of N-Myc3,31. Remarkably, LIF removal from Huwe1-null ES cells failed to cause downregulation of N-Myc and upregulation of p27Kip1 (Fig. 3a). In Huwe1-null cells we observed only minimal elevation of c-Myc (Figs 3a, 4a). Huwe1 mRNA levels remained unchanged throughout the course of the experiment, whereas that of N-myc and c-myc mRNA gradually decreased in a manner that was indistinguishable in wild-type and Huwe1-null ES cells (Fig. 3b). Thus, the observed protein changes in Huwe1-null ES cells were not secondary to changes in the corresponding mRNAs. Moreover, Huwe1-null ES cells deprived of LIF showed elevated expression of CDC25A32 and Top1 (refs 33, 34), and decreased expression of N-cadherin35 and Serpine1 (refs 33, 36), which are induced and repressed Myc target genes, respectively (Fig. 3c). Consistent with the notion that N-Myc is a more efficient substrate than c-Myc, we found that knockout of Huwe1 in ES cells stabilized N-Myc more efficiently than c-Myc (Fig. 3d–f).

Figure 3.

Genetic inactivation of Huwe1 impairs N-Myc degradation. (a) Wild-type and Huwe1-trapped ES cells were plated in the presence of LIF and 18 h later deprived of LIF for the indicated times. Lysates were analysed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (b) Parallel cultures were analysed for expression of Huwe1, N-myc, c-myc and β-actin by semi-quantitative RT–PCR. (c) Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT–PCR) analysis of the mRNA of selected Myc target genes in wild-type and Huwe1-trapped ES cells. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3; *P < 0.01 **P < 0.001 Student's t-test). (d) Wild-type and Huwe1-trapped ES cells were treated with CHX for the indicated times 24 h after LIF deprivation. Lysates were analysed by western blotting using anti-N-Myc and anti-c-Myc antibodies. β-actin is shown as a control for loading. (e) Quantification of N-Myc from the experiment in d. (f) Quantification of c-Myc from the experiment in d. Full scans of immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S9.

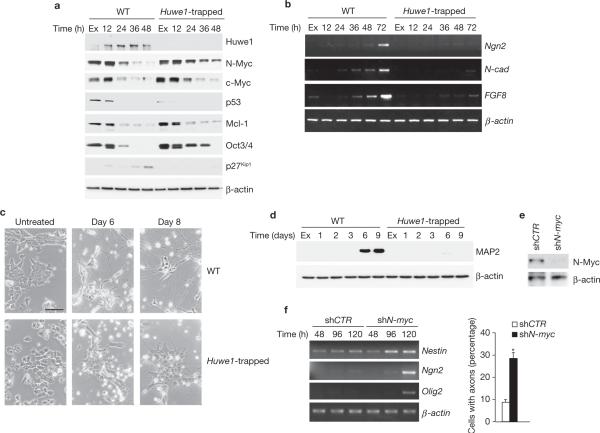

Figure 4.

Blockade of neuronal differentiation by genetic inactivation of Huwe1 is rescued by silencing of N-myc. (a) Wild-type and Huwe1-trapped ES cells were plated in differentiation medium and collected at the indicated times. Lysates were analysed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (b) Cells treated as in a were examined for gene expression by semi-quantitative RT–PCR. (c) Cells cultured for 4 days in differentiation medium were trypsinized and re-plated in the same medium on poly-d-lysine- and laminin-coated dishes. Bright-field images were taken 2 (day 6) and 4 (day 8) days after re-plating. Scale bar is 40 μm. (d) Cultures treated as in c were collected at the indicated times and analysed by immunoblotting using the neuronal marker MAP2. (e) Cells transduced with lentivirus expressing shRNA against N-myc or control lentivirus were analysed by western blotting using antibodies directed against N-Myc. β-actin is shown as a control for loading. (f) Cells treated as in e were plated in differentiation medium, collected at the indicated times and examined for gene expression by semi-quantitative RT–PCR (left panel). The number of cells showing axonal projections was scored. At least 1,500 cells were counted from 36 randomly chosen fields (right panel). Results are mean ± s.e.m. (*P = 4.7 × 10−8, Student's t-test, n = 3). Full scans of immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S9.

The differentiation pathways induced in ES cells after LIF removal are heterogeneous and poorly controlled. In contrast, ES cells plated on gelatin-coated tissue culture dishes in a serum-free medium supporting neural differentiation (N2-B27) commit synchronously along the neural fate and undergo terminal neuronal differentiation37. Under these conditions, N-Myc rapidly decreased and became undetectable 48 h after neuronal induction. Complete loss of the stem-cell markers Oct3/4 occurred within 24−36 h and was associated with elevation of Huwe1 and p27Kip1 (Fig. 4a). In contrast, in Huwe1 knockout cells the stability of N-Myc was increased, N-Myc levels were preserved, downregulation of Oct3/4 was delayed and p27Kip1 was not induced. Consistent with these findings, Mcl1 and c-Myc were slightly upregulated but p53 was not increased in Huwe1-null ES cells (Fig. 4a). Because elimination of N-Myc is required for neuronal differentiation38–40, we asked whether persistent levels of N-Myc, caused by loss of Huwe1, impair neuronal differentiation of ES cells. Three early markers of neuronal differentiation (Neurogenin2 (Ngn2), N-cadherin (N-cad) and FGF8, ref 41–43) were induced in wild-type ES cells by 72 h of growth in the neural culture system but remained undetectable in Huwe1-null ES cells (Fig. 4b). Failure to induce Neurogenin2, N-cadherin and FGF8 was associated with the absence of morphological signs of neuronal differentiation in Huwe1-null cultures (less than 10% of cells displayed neurite extension) following re-plating on poly-d-lysine in neural medium. In contrast, 90% of wild-type ES cells extended long neurites and reached a highly organized and networked neuronal differentiation (Fig. 4c). Accordingly, the expression of MAP2, a marker of mature neurons, was induced in wild-type ES cells but remained undetectable in the absence of Huwe1 (Fig. 4d). Next, we sought to determine whether N-Myc is the functionally critical degradation substrate of Huwe1 in ES cells primed to differentiate along the neuronal lineage. To do this, we suppressed expression of N-myc in Huwe1-null cells to determine whether this manipulation would restore differentiation. Indeed, lentivirus-mediated silencing of N-Myc rescued neuronal differentiation and expression of neuronal markers in Huwe1-knockout ES cells (Fig. 4e, f). Thus, the aberrant accumulation of N-Myc in the absence of Huwe1 is the crucial event that prevents neuronal differentiation of ES cells.

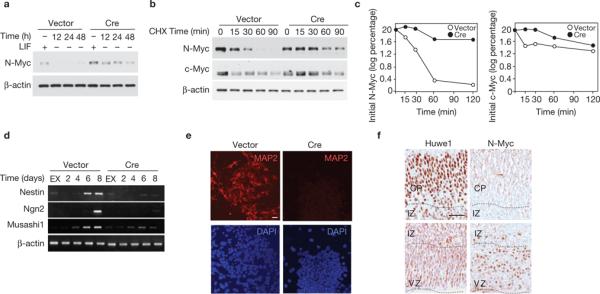

To extend our analysis of Huwe1-null ES cells to a conditional knockout system, we generated a floxed allele of murine Huwe1 with LoxP sites flanking exons 80 and 82, which encode the HECT domain. Cre-mediated recombination of the only Huwe1flox allele in male Huwe1flox/y ES cells produced a Huwe1ΔHECT allele, which lacks the HECT domain (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3). Cre-mediated inactivation of Huwe1 severely impaired the ability of ES cells to downregulate N-Myc following LIF withdrawal (Fig. 5a). Accordingly, N-Myc turnover was reduced more than 5-fold in Huwe1ΔHECT ES cells grown in the absence of LIF, compared with Huwe1flox (N-Myc half-life in Huwe1flox: 15 min; Huwe1ΔHECT: 86 min). Again, Huwe1 inactivation had a smaller effect on the stability of c-Myc (Fig. 5b, c). Consistent with the findings in ES cells carrying a trapped Huwe1 allele, conditional inactivation of Huwe1 impaired induction of neuronal markers and prevented neuronal differentiation under experimental conditions in which those effects were readily observed in Huwe1flox ES cells (Fig. 5d, e). Conversely, neuronal differentiation was unaffected in wild-type ES cells expressing the Cre recombinase, indicating that expression of Cre does not impair neuronal differentiation of ES cells (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4). We also examined whether elimination of N-Myc in Huwe1-expressing cells also operates in the nervous system in vivo. Immunohistochemistry for Huwe1 and N-Myc in the mouse cortex at embryonic day 15.5 (E15.5) showed high levels of N-Myc in neural progenitors located in the germinal layers of the telencephalon but low levels of Huwe1. Conversely, N-Myc was absent in the differentiated neurons of the cortical plate. The expression of Huwe1 showed a marked increasing gradient as neuronal differentiation proceeded such that the cortical plate contained the highest levels of Huwe1, compared with other mouse tissues at this stage of development (Fig. 5f; Supplementary Information, Fig. S5a and data not shown).

Figure 5.

Conditional knockout of Huwe1 impairs neuronal differentiation in ES cells. (a) ES cells carrying a targeted Huwe1 allele (Huwe1Flox) were infected with retroviral vectors encoding GFP (Vector) or Cre–IRES–GFP (Cre). Cells were deprived of LIF for the indicated times and lysates were analysed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (b) Vector-and Cre-infected Huwe1Flox ES cells were treated with CHX for the indicated times 24 h after LIF deprivation. Lysates were analysed by immunoblotting. (c) Quantification of N-Myc (left panel) and c-Myc (right panel) from vector- (empty circles) and Cre- (filled circles) infected cells. (d) Analysis of gene expression by semi-quantitative RT–PCR of embryoid bodies derived from vector- and Cre-transduced Huwe1Flox ES cells at different times. (e) Embryoid bodies derived from Vector- and Cretransduced Huwe1Flox ES cells were allowed to adhere after being cultured in suspension for 8 days. After 48 h embryoid bodies were analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy for MAP2. Samples were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar is 20 μm. (f) Expression of Huwe1 was induced in differentiated neural cells. Adjacent sections of paraffin embedded E15.5 mouse embryos were processed for immunohistochemistry using anti-Huwe1 or anti-N-Myc antibodies. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin. CP, cortical plate; IZ, intermediate zone; VZ, ventricular zone. Scale bar is 40 μm. Full scans of immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S9.

The Huwe1–N-Myc pathway controls proliferation and differentiation in the developing brain

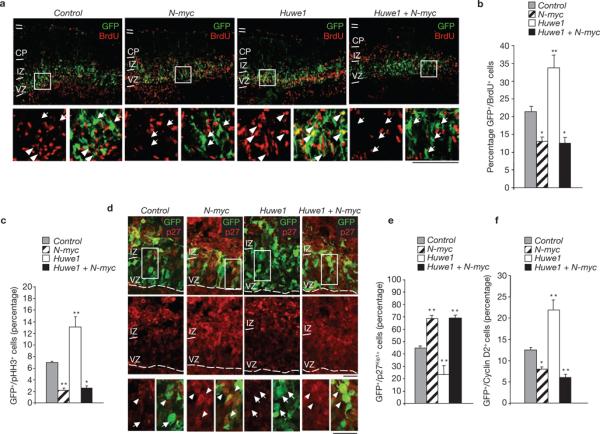

To determine whether Huwe1 directs cell-cycle arrest and neuronal differentiation in the developing brain by restraining the accumulation of N-Myc, we silenced Huwe1 and N-myc by ex vivo electroporation of the cortical germinal layers at mid-gestation, followed by organotypic slice culture44,45. Successfully electroporated cells were monitored by co-expression of GFP. Electroporation of specific siRNA oligonucleotides efficiently silenced the expression of Huwe1 and N-myc, and knockdown of Huwe1 elevated N-Myc (Supplementary Information, Fig. S5). To analyse proliferation, cortices from E14.5 mouse embryos were electroporated with control siRNAs or siRNAs targeting N-myc, Huwe1 and N-myc–Huwe1 and then cultivated in the presence of BrdU. Consistent with the effects of N-myc knockout in the nervous system3, silencing of N-myc caused a notable decrease in cycling cells, as measured by quantitative immunostaining for BrdU (Fig. 6a, b) and phospho-histone H3 (pHH3, Fig. 6c; Supplementary Information, Fig. S6). Knockdown of Huwe1 produced the opposite effect, namely an increase in the fraction of proliferating cells, indicating that Huwe1 promotes cell-cycle exit of cortical progenitors. Consistent with the finding that Huwe1 operates as an upstream, negative regulator of N-Myc, concurrent silencing of Huwe1 and N-myc abolished the phenotypic consequences of Huwe1 inactivation and led to a proliferation defect that was indistinguishable from that observed in N-myc-knockdown cortices (Fig. 6a–c; Supplementary Information, Fig. S6). Neither N-myc nor Huwe1 manipulation caused detectable changes in the fraction of apoptotic cells, as determined by quantitative immunostaining for caspase-3 and p53 (Supplementary Information, Fig. S7a–d). Targeted deletion of N-myc in neural stem cells leads to derepression of p27Kip1 and loss of the N-Myc target gene cyclin D2, two events considered crucial for the premature cell-cycle exit phenotype observed in N-myc-null brains3. To determine whether the Huwe1–N-Myc pathway also converges on p27Kip1 and cyclin D2, we monitored expression of p27Kip1 and cyclin D2 in cortices with silenced N-myc and Huwe1. As expected, p27Kip1 was elevated and cyclin D2 decreased in N-myc knockdown cells, whereas p27Kip1 was decreased and cyclin D2 upregulated in Huwe1-silenced cortices. p27Kip1 remained elevated and cyclin D2 repressed in cells with combined silencing of N-myc and Huwe1 (Fig. 6d–f; Supplementary Information, Fig. S8).

Figure 6.

The Huwe1–N-Myc pathway in the developing brain. (a) Ex vivo electroporation of control, N-myc, Huwe1 and N-myc + Huwe1 siRNA into E13.5 mouse cortices followed by organotypic slice culture for 1.5 days. Cortical slices were double-labelled with BrdU (red) and GFP (green) to identify transfected cells. Scale bars are 100 μm. (b) Quantification of GFP-positive/BrdU-positive cells. (c) Quantification of GFP-positive/pHH3-positive cells. (d) Cortical slices were double-labelled with p27Kip1 (red) and GFP (green). Scale bars are 50 μm. (e) Quantification of GFP-positive/p27Kip1-positive cells. (f) Quantification of GFP-positive/Cyclin D2-positive cells. Results shown are mean ± s.e.m. of three sections from one experiment (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student's t-test). Arrowheads indicate GFP-positive/Cy3-positive cells; arrows indicate GFP-positive/Cy3-negative cells. IZ, intermediate zone; VZ, ventricular zone.

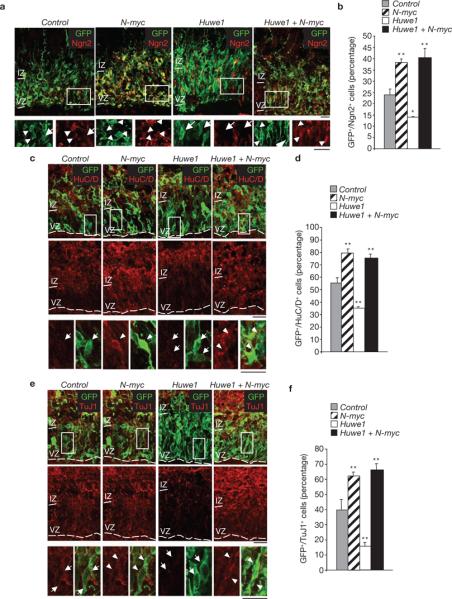

Ectopic expression of p27Kip1 in the developing brain triggers premature differentiation by stabilizing Neurogenin2 (Ngn2) and consequent activation of neuronal differentiation markers44. Perturbation of the Huwe1–N-Myc pathway led to profound changes in the expression of Ngn2 and consequently in the differentiation status of the electroporated cortices. Ngn2 is increased in the absence of N-Myc and the same effect was observed when N-myc and Huwe1 were concurrently silenced. However, the simple knockdown of Huwe1 was associated with marked depletion of Ngn2 from Huwe1-null cells (Fig. 7a, b). Finally, we analysed the expression of early (HuC/D, Fig. 7c) and late (TuJ1, Fig. 7e) markers of neuronal differentiation. HuC/D and TuJ1 were mostly absent in the control ventricular and subventricular areas, whereas they were readily detected in the intermediate zone and cortical plate. However, a large fraction of HuC/D- and TuJ1-positive cells were detected in the ventricular/subventricular areas of N-myc-silenced cortices, a result which is consistent with the notion that N-Myc prevents premature differentiation of cortical progenitors. In contrast, Huwe1-null cortices showed a disproportionately reduced number of HuC/D- and TuJ1-positive cells, even in the intermediate zone and cortical plate, indicating that loss of Huwe1 induces a differentiation defect. Again, concurrent knockdown of N-myc and Huwe1 overcame the effects caused by Huwe1 depletion and led to a precocious differentiation phenotype that was identical to the isolated silencing of N-myc (Fig. 7c–f). Therefore, we conclude that Huwe1 is essential for initiation of cell-cycle exit and differentiation in vivo and these events are mediated by the elimination of N-Myc from cortical progenitors.

Figure 7.

Silencing of Huwe1 blocks differentiation of neural progenitors in vivo. (a) Ex vivo electroporation of control, N-myc, Huwe1 and Huwe1 + N-myc siRNA into E13.5 mouse cortices followed by organotypic slice culture for 1.5 days. Cortical slices were double-labelled with Neurogenin2 (Ngn2, red) and GFP (green) to identify transfected cells. (b) Quantification of GFP-positive/Ngn2-positive cells. (c) Cortical slices were double-labelled with the early neuronal marker HuC/D (red) and GFP (green). (d) Quantification of GFP-positive/HuC/D-positive cells. (e) Cortical slices were double-labelled with the mature neuronal marker Tuj1 (red) and GFP (green). (f) Quantification of GFP-positive/Tuj1-positive cells. Results shown in b, d and f are mean ± s.e.m. of four sections for Ngn2, three sections for HuC/D and three sections for TuJ1 from one experiment; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student's t-test). Arrowheads indicate GFP-positive/Cy3-positive cells; arrows indicate GFP-positive/Cy3-negative cells. Scale bars are 50 μm. IZ, intermediate zone; VZ, ventricular zone.

DISCUSSION

In this study we examined the biological role of Huwe1, a HECT-domain E3 ubiquitin ligase whose properties and function in vivo were unclear. We demonstrated the existence of a Huwe1–N-Myc pathway, in which Huwe1 operates on a linear pathway epistatic to N-Myc to allow neuronal differentiation and cell-cycle arrest of stem cells and cortical progenitors. We discovered that the phenotypic and molecular changes resulting from Huwe1 knockdown are fully reversed when expression of the N-myc gene is also silenced. Through experiments conducted in ES cells and neural progenitors in vivo, we showed that the mechanistic explanation for the above findings is the ability of Huwe1 to bind to N-Myc and prime it for Lys 48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal-mediated degradation.

The Lys 48-mediated mechanism of ubiquitin linkage on N-Myc by Huwe1 and its recognition by the 26S proteasome for destruction is consistent with in vitro and in vivo observations in neuroblastoma cells, differentiating ES cells and developing brain where silencing of Huwe1 expression invariably results in N-Myc accumulation and an extended half-life. Although a previous study found that c-Myc is also a substrate of Huwe1-mediated ubiquitination, it suggested that the polyubiquitin chains are mostly linked through Lys 63 and do not target degradation of c-Myc by the proteasome16. However, in this study, Huwe1 seemed to assemble different types of polyubiquitin chains (Lys 11, Lys 48, Lys 63). Here, we have conducted a detailed functional comparison of N-Myc and c-Myc as Huwe1 substrates. This analysis led to three conclusions. First, N-Myc and c-Myc are both ubiquitinated in vivo by Huwe1 through Lys 48-mediated linkages (Fig. 2d, e). Second, ubiquitination of N-Myc by Huwe1 is markedly more efficient than ubiquitination of c-Myc under identical experimental conditions (Fig. 2b). This effect is probably the consequence of a more efficient interaction of Huwe1 with N-Myc than with c-Myc (Fig. 1d). Third, constitutive and conditional genetic knockout of Huwe1 in ES cells results in the stabilization of endogenous N-Myc and c-Myc, albeit with markedly different rates (N-Myc stabilization is at least 3-fold more pronounced than c-Myc, Figs 3d–f, 5b, c).

The rather poor efficiency by which c-Myc binds, is ubiquitinated and degraded by Huwe1 may be one of the reasons for the failure to observe stabilization of c-Myc in cells where residual Huwe1 expression may still be present after RNA-interference-mediated silencing16. Furthermore, in the previous study, the ubiquitination assays were performed using a truncated version of Huwe1 that lacks the first 2472 amino acids16, whereas we have used full-length Huwe1 for all our experiments. Finally, the observation that Huwe1 assembles only Lys 48-mediated linkages on its substrates is consistent with that of a recent report in which a combination of ubiquitin mutagenesis and mass spectrometry experiments revealed that HECT-domain E3 ligases can only form homogeneous ubiquitin chains (Lys 48 or Lys 63; ref. 24).

The most striking effect that emerged from inactivation of Huwe1 in ES cells and developing brain is the impaired differentiation along the neuronal lineage. We suggest that the activity of Huwe1 as negative regulator of N-Myc provides a mechanistic explanation for this observation. Support for this idea comes from the sharp gradient of Huwe1 expression in the developing central nervous system, whereby Huwe1 is markedly upregulated as neuronal differentiation proceeds. Accordingly, the cortical plate, which contains only post-mitotic and differentiated neurons that are invariably N-Myc-negative, is the area in the mouse embryo with the highest expression of Huwe1 at mid-gestation. Furthermore, the conclusion that Huwe1 operates on a linear pathway epistatic to N-Myc is firmly supported by the notion that concurrent silencing of Huwe1 and N-myc not only rescues the differentiation defect of Huwe1-null neurons but actually converts it into a premature cell-cycle exit/differentiation phenotype that is indistinguishable from that produced by single knockdown of N-myc. As well as protecting post-mitotic neurons from re-expression of N-Myc, thus preventing cell-cycle re-entry and loss of the differentiated state, the high levels of Huwe1 expression in the cortical plate may also be necessary to target other substrates possibly implicated in specialized neuronal activities. Consistent with this hypothesis is a recent screening in Caenorhabditis elegans, from which Huwe1 emerged as an essential gene for synaptogenesis46. However, Huwe1 substrates regulating synaptogenesis have not been found. Regardless of the full scope of Huwe1 substrates in differentiated neurons, our findings indicate that N-Myc is the crucial substrate in differentiating neural progenitors and identify the Huwe1–N-Myc pathway as a key modulator of differentiation and quiescence in the neural tissue.

METHODS

Cell culture

IMR32, SK-N-SH and U2OS cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). U2OS cells stably expressing N-Myc were generated by transfecting cells with the retroviral vector pLZRS–IRES–GFP or pLZRS–IRES–GFP–N-Myc and selected in 2 μg ml−1 of puromycin. Cell transfection was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). siRNAs were Huwe1 Smart Pool (Dharmacon). LaminA/C and firefly luciferase Smart Pools (Dharmacon) were used as negative controls. Retroviral infection was performed as described previously19. E14Tg2a-derived 46C ES cells (sox1–GFP knock-in ES cells) were a gift from Austin Smith37. RRE249 and HMA095 cells, also derived from E14Tg2a ES cells were obtained from BayGenomics. Undifferentiated mouse ES cells were maintained on gelatin-coated dishes in Glasgow minimal essential medium (GMEM, Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) and 1,000 U ml−1 of LIF (Chemicon). For neural differentiation, undifferentiated ES cells were dissociated and plated onto poly-d-lysine- and laminin-coated tissue culture plastic at a density of 3 × 104 cells/cm2 in N2B27 medium. The medium was replaced every 2 days. N2/B27 is a 1:1 mixture of DMEM-F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with modified N2 (25 μg ml−1 insulin, 100 μg ml−1 apo-transferrin, 6 ng ml−1 progesterone, 16 μg ml−1 putrescine, 30 nM sodium selenite, 50 μg ml−1 bovine serum albumin fraction V and neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen). Embryoid bodies were obtained by plating ES cells onto ultra-low-attachment 6-well plates (Invitrogen) at 2 × 105 cells ml−1 in medium for ES cell culture without LIF. The medium was changed every other day. Retinoic acid (1 μM) was added from day 4 to day 8 (ref. 47).

For lentiviral transduction, Huwe1-trapped ES cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 per well in 6-well plates and infected with control or lentivirus containing a short hairpin (sh) RNA sequence targeting N-myc (SHGLYC–TRCN0000020696, Sigma). Cells were treated according to the differentiation protocol described above, under adherent conditions 3 days after infection.

Biochemical methods

Extract preparation, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as described previously13.

Ex vivo electroporation, cell counting and statistics

Ex vivo electroporation was performed as described previously44. Embryonic mouse heads were isolated from E14.5 pregnant mice. Endotoxin-free GFP plasmid (1 μg μl−1), siRNA (10 μM, N-myc, Huwe1 and Control Smart Pool, Dharmacon) and fast green (Sigma) as an indicator were injected into lateral ventricles using a Femtojet microinjector (Eppendorf). The head was then electroporated using platinum electrodes (Nepagene) and an ECM 830 electroporator (BTX) with the following parameters: 50 V, pulse duration 50 ms, pulse interval 1 s, and 5 pulses. Electroporated cerebral hemispheres were dissected and sectioned coronally into 300-μm-thick slices using a vibratome (VT1000S, Leica). The slices were cultured for 1.5 or 3 days in neurobasal medium containing 1% N2, 1% B27, 2 mM l-glutamine and penicillin–streptomycin/1% fungizone/5 μg ml−1 ciprofloxacine. For BrdU immunostaining, slices were labelled with 10 μM BrdU for 2 h before fixation. Slices were fixed in ice cold 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 2 h. After overnight incubation in PBS containing 20% sucrose, slices were embedded in OCT and kept at −80 °C. Cryostat sections were stained according to standard protocols using FITC and Cy3–conjugated secondary antibodies. In all experiments slices from two independent experiments were processed for each experimental condition. For each sample at least 3 adjacent sections were analysed by confocal microscopy and ×40 magnified fields zoomed ×1.5 were acquired. Experiments were repeated twice with similar results. Cells that were positive for GFP and Cy3 were scored. Results are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test between control and experimental condition, or one-way ANOVA (ANOVA-1) followed by a Dunnett's post hoc test for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism software, version 3.03).

RT–PCR

Total RNA was prepared with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT–PCR) was performed using a 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) and iTaqTM SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences for mouse genes are available in the Supplementary Information.

In vitro ubiquitination assay

Baculoviral expression and purification of full-length wild-type Huwe1 and Cys 4341 to Ala mutant Huwe1 (Huwe1–CA) were described previously14. Ubiquitination and degradation assays were performed as previously described13,48. Briefly, N-Myc and c-Myc ubiquitination was performed in a volume of 10 μl containing 2 μl of a 5× stock of a reaction mix (0.25 M Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 50 mM phosphocreatine and 17.5 U ml−1 creatine phosphokinase, 0.1−2 μl of recombinant wild-type Huwe1 or 2 μl Huwe1–CA, 1.5 ng μl−1 E1 (Boston Biochem), 10 ng μl−1 UbcH5, 2.5 μg μl−1 ubiquitin (Sigma), 1 μl 35S-methionine-labelled in vitro transcribed/translated N-Myc and c-Myc as substrate. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h or the indicated times and analysed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. Where indicated, wild-type ubiquitin was substituted with ubiquitin mutants (K48R, K63R or K48/63R). Degradation assays were performed in the presence or absence of 20 nM purified 26S proteasomes. After incubation at 37 °C for various times, reactions were stopped by the addition of sample buffer and subjected to SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography.

In vivo ubiquitination assay

U2OS cells stably transfected with pLZRS–IRES– GFP–N-Myc were cotransfected with pCDNA-V5 vector or pCDNA-V5–Huwe1 plus wild-type pCMV–HA–Ubiquitin, pCMV–HA–Ubiquitin–Lys 48 only (K48O) or pCMV–HA–Ubiquitin–Lys 63 only (K63O). Thirty-six hours after transfection, cells were treated with 5 μm MG132 for 3 h and then lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer containing 0.5% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycolate and 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Identical aliquots of cell lysates (2 mg) were used in immunoprecipitation assays with anti-N-Myc (Calbiochem) or anti-c-Myc (Santa Cruz) monoclonal antibodies. Immunocomplexes were resolved on 4−12% gradient gels and immunoblotting was performed using an anti-HA antibody (Roche). Total lysates (20 μg) were used for immunoblotting to evaluate the expression of V5-Huwe1 and HA–ubiquitins.

Generation of conditionally mutant Huwe1 ES cells

The Huwe1 conditional allele (Huwe1flox) was created by inserting an Frt-flanked pGKNeoR cassette into intron 82 and loxP sites into intron 79 and 82. Exons 80−82 encode most of the HECT domain of Huwe1. Cre-mediated recombination results in the removal of 197 amino acids. After homologous recombination in AB2.2 ES cells (gift from Allan Bradley, Wellcome Trust, Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK), an expression vector of Cre recombinase was transiently transfected to delete the pGKNeoR cassette and exons 80−82 of Huwe1. The conditional floxed allele was genotyped using primers flanking the 5′ and 3′ loxP sites. The floxed allele produced a 4.6 kb genomic PCR product, the wild-type allele produced a 2.8 kb product and the floxed, recombined allele produced a 0.55 kb PCR product. RT–PCR using primers in exons 81 and 83 confirmed successful deletion of exons 80−82 in ES cells infected with Cre–IRES–GFP retrovirus but not in cells infected with GFP retrovirus.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Nicholas Sherman for mass spectrometry analyses, Simon Wing for anti-Huwe1 (Lasu1) antibodies, Xiaodong Wang for the pFastBac-1–Mule1, Wei Gu for V5-Huwe1–N and V5–Huwe1–C expression vectors, Richard Baer for pCMV–HA–ubiquitin expression plasmids and George DeMartino for the purified 26S proteasome. We are indebted to Austin Smith for 46C ES cells and for advice on neural differentiation in adherent culture, and to Allan Bradley for AB2.2 ES cells. We thank Yong-Seok Ho for preparation of recombinant Huwe1 proteins and technical support. This work was supported by grants from the NIH to A.L., A.I. and M.P. and an Emerald Foundation grant to D.G. D.G. is supported by a fellowship from Provincia di Benevento, Italy. J.H. is funded by the Australian NHMRC (ID:310616) and work in the F.G. laboratory is funded in part by an institutional grant from the Medical Research Council (UK).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.L. conducted the initial purification of the N-Myc complexes; A.L., X.Z. and R.J. performed most of the experiments; D.G. performed the experiments shown in Fig. 2f under the supervision of M.P.; X.Z. and J.I.-T.H. performed the ex vivo electroporation experiments under the supervision of F. G.; M.P. provided reagents and suggestions; A.L. and A.I. coordinated the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Stanton BR, Perkins AS, Tessarollo L, Sassoon DA, Parada LF. Loss of N-Myc function results in embryonic lethality and failure of the epithelial component of the embryo to develop. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2235–2247. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanton BR, Parada LF. The N-Myc proto-oncogene: developmental expression and in vivo site-directed mutagenesis. Brain Pathol. 1992;2:71–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knoepfler PS, Cheng PF, Eisenman RN. N-Myc is essential during neurogenesis for the rapid expansion of progenitor cell populations and the inhibition of neuronal differentiation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2699–2712. doi: 10.1101/gad.1021202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenney AM, Cole MD, Rowitch DH. N-Myc upregulation by sonic hedgehog signaling promotes proliferation in developing cerebellar granule neuron precursors. Development. 2003;130:15–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenney AM, Widlund HR, Rowitch DH. Hedgehog and PI-3 kinase signaling converge on N-Myc1 to promote cell cycle progression in cerebellar neuronal precursors. Development. 2004;131:217–228. doi: 10.1242/dev.00891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seeger RC, et al. Expression of N-Myc by neuroblastomas with one or multiple copies of the oncogene. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1988;271:41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonvini P, Nguyen P, Trepel J, Neckers LM. In vivo degradation of N-Myc in neuroblastoma cells is mediated by the 26S proteasome. Oncogene. 1998;16:1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciechanover A, et al. Degradation of nuclear oncoproteins by the ubiquitin system in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:139–143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciechanover A, DiGiuseppe JA, Schwartz AL, Brodeur GM. Degradation of MYCN oncoprotein by the ubiquitin system. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1991;366:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross-Mesilaty S, et al. Basal and human papillomavirus E6 oncoprotein-induced degradation of Myc proteins by the ubiquitin pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8058–8063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheffner M, Nuber U, Huibregtse JM. Protein ubiquitination involving an E1-E2-E3 enzyme ubiquitin thioester cascade. Nature. 1995;373:81–83. doi: 10.1038/373081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lasorella A, et al. Degradation of Id2 by the anaphase-promoting complex couples cell cycle exit and axonal growth. Nature. 2006;442:471–474. doi: 10.1038/nature04895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong Q, Gao W, Du F, Wang X. Mule/ARF–BP1, a BH3-only E3 ubiquitin ligase, catalyzes the polyubiquitination of Mcl-1 and regulates apoptosis. Cell. 2005;121:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen D, et al. ARF–BP1/Mule is a critical mediator of the ARF tumor suppressor. Cell. 2005;121:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adhikary S, et al. The ubiquitin ligase HectH9 regulates transcriptional activation by Myc and is essential for tumor cell proliferation. Cell. 2005;123:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotta CV, et al. The helix-loop-helix protein Id2 is expressed differentially and induced by Myc in T-cell lymphomas. Cancer. 2008;112:552–561. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galvin KE, Ye H, Wetmore C. Differential gene induction by genetic and ligand-mediated activation of the Sonic hedgehog pathway in neural stem cells. Dev. Biol. 2007;308:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasorella A, Noseda M, Beyna M, Yokota Y, Iavarone A. Id2 is a retinoblastoma protein target and mediates signalling by Myc oncoproteins. Nature. 2000;407:592–598. doi: 10.1038/35036504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zippo A, De Robertis A, Serafini R, Oliviero S. PIM1-dependent phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 is required for Myc-dependent transcriptional activation and oncogenic transformation. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:932–944. doi: 10.1038/ncb1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deb-Basu D, Karlsson A, Li Q, Dang CV, Felsher DW. MYC can enforce cell cycle transit from G1 to S and G2 to S, but not mitotic cellular division, independent of p27-mediated inihibition of cyclin E/CDK2. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1348–1355. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.12.2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen-Durr P, et al. Differential modulation of cyclin gene expression by MYC. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:3685–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connell BC, et al. A large scale genetic analysis of c-Myc-regulated gene expression patterns. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:12563–12573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HT, et al. Certain pairs of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) and ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) synthesize nondegradable forked ubiquitin chains containing all possible isopeptide linkages. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:17375–17386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chau V, et al. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short-lived protein. Science. 1989;243:1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thrower JS, Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M, Pickart CM. Recognition of the polyubiquitin proteolytic signal. EMBO J. 2000;19:94–102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortunel NO, et al. Comment on “ ‘Stemness’: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells” and “a stem cell molecular signature”. Science. 2003;302:393. doi: 10.1126/science.1086384. author reply 393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivanova NB, et al. A stem cell molecular signature. Science. 2002;298:601–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramalho-Santos M, Yoon S, Matsuzaki Y, Mulligan RC, Melton DA. “Stemness”: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells. Science. 2002;298:597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1072530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith AG. Embryo-derived stem cells: of mice and men. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;17:435–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zindy F, et al. N-Myc and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p18Ink4c and p27Kip1 coordinately regulate cerebellar development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11579–11583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604727103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galaktionov K, Chen X, Beach D. Cdc25 cell-cycle phosphatase as a target of c-Myc. Nature. 1996;382:511–517. doi: 10.1038/382511a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez PC, et al. Genomic targets of the human c-Myc protein. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1115–1129. doi: 10.1101/gad.1067003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Hagan RC, et al. Gene-target recognition among members of the Myc superfamily and implications for oncogenesis. Nature Genet. 2000;24:113–119. doi: 10.1038/72761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson A, et al. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menssen A, Hermeking H. Characterization of the c-MYC-regulated transcriptome by SAGE: identification and analysis of c-MYC target genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6274–6279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082005599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying QL, Stavridis M, Griffiths D, Li M, Smith A. Conversion of embryonic stem cells into neuroectodermal precursors in adherent monoculture. Nature Biotechnol. 2003;21:183–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernard O, Drago J, Sheng H. L-Myc and N-Myc influence lineage determination in the central nervous system. Neuron. 1992;9:1217–1224. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90079-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bogenmann E, Torres M, Matsushima H. Constitutive N-Myc gene expression inhibits trkA mediated neuronal differentiation. Oncogene. 1995;10:1915–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peverali FA, et al. Retinoic acid-induced growth arrest and differentiation of neuroblastoma cells are counteracted by N-Myc and enhanced by max overexpressions. Oncogene. 1996;12:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belachew S, et al. Postnatal NG2 proteoglycan-expressing progenitor cells are intrinsically multipotent and generate functional neurons. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:169–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teng J, et al. The KIF3 motor transports N-cadherin and organizes the developing neuroepithelium. Nature Cell Biol. 2005;7:474–482. doi: 10.1038/ncb1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C, et al. Cell aggregation-induced FGF8 elevation is essential for P19 cell neural differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:3075–3084. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen L, et al. p27kip1 independently promotes neuronal differentiation and migration in the cerebral cortex. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1511–1524. doi: 10.1101/gad.377106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hand R, et al. Phosphorylation of Neurogenin2 specifies the migration properties and the dendritic morphology of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex. Neuron. 2005;48:45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sieburth D, et al. Systematic analysis of genes required for synapse structure and function. Nature. 2005;436:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nature03809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bain G, Kitchens D, Yao M, Huettner JE, Gottlieb DI. Embryonic stem cells express neuronal properties in vitro. Dev Biol. 1995;168:342–357. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bloom J, Amador V, Bartolini F, DeMartino G, Pagano M. Proteasome-mediated degradation of p21 via N-terminal ubiquitinylation. Cell. 2003;115:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.