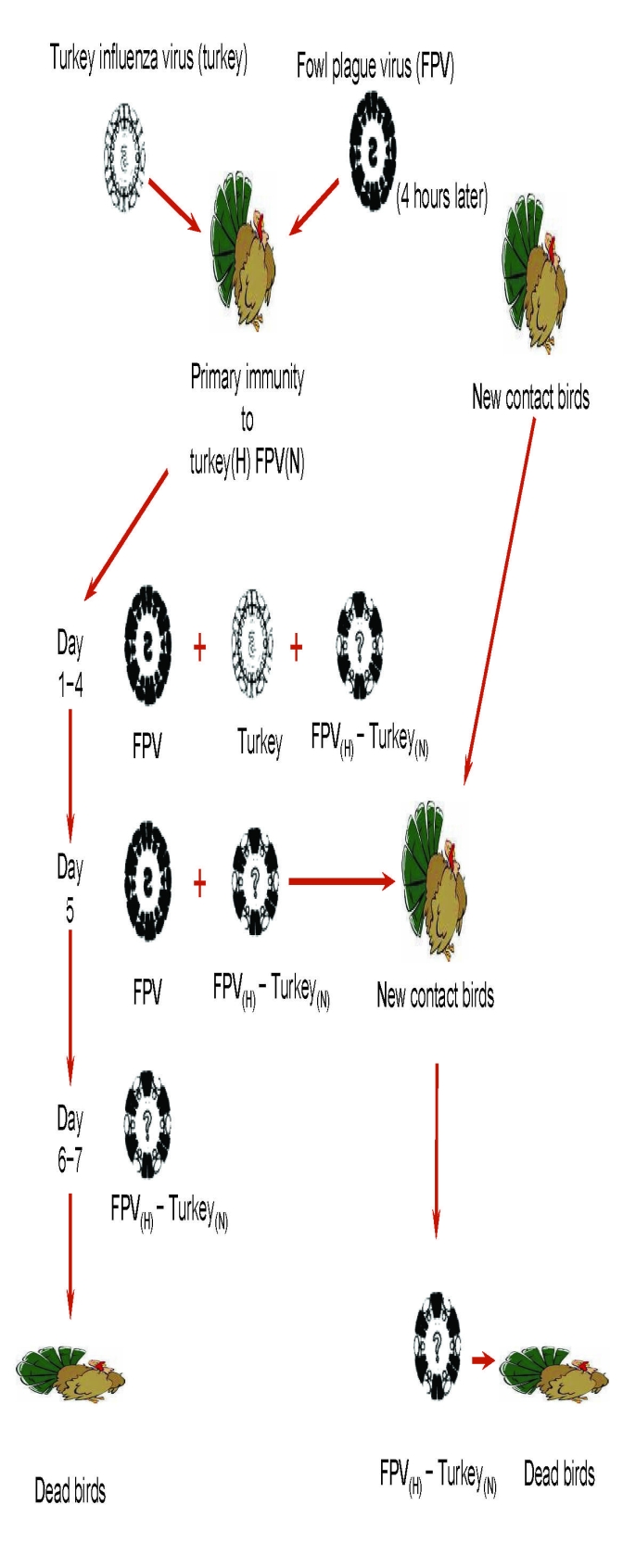

Figure.

Genetic reassortment and genesis of a new pandemic influenza virus. This study was designed to determine whether the selection and transmission of a new reassortant influenza A virus could occur under experimental conditions in vivo that mimic what might occur in nature. Reassortment between 2 antigenically distinct influenza A viruses was studied in turkeys that had been previously immunized to induce low levels of antibodies to the hemagglutinin (H) of a nonlethal turkey influenza virus (Turkey), and to the neuraminidase (N) of a fowl plague virus (FPV), an avian virus that is highly pathogenic for chickens. Twenty-eight days after immunization, the immunized turkeys were sequentially infected, first with the Turkey virus and 4 h later with FPV. During the first few days, both parent viruses were isolated from the infected turkeys, but by day 4 a reassortant virus containing the FPV hemagglutinin and the Turkey neuraminidase (FPV(H)–Turkey(N)) was also isolated; within 2 days it became the dominant virus. All infected turkeys died, and only the FPV(H)–Turkey(N) reassortant virus could be recovered. In a separate experiment, similarly immunized turkeys were again sequentially infected, but on day 5 a group of nonimmunized or selectively immunized turkeys (Turkey(H) FPV(N)) were placed in the same room. All contact birds soon died of fulminant infection caused by the FPV(H)–Turkey(N) reassortant virus. These experiments demonstrated that under conditions of selective primary immunity, a new virus could be generated through genetic reassortment in vivo and that this reassortant virus could be readily transmitted to contacts. The reassortant virus caused uniformly fatal disease in primary infected and contact birds. Thus, under the conditions of these experiments, genetic reassortment gave rise to a new influenza virus that led to a total population collapse. Adapted from Webster and Campbell (9).