Abstract

Context:

Employment opportunities for athletic trainers (ATs) in the high school setting have increased greatly in the past few years and will most likely continue to increase. Understanding what attracts individuals to become ATs and work in the high school setting is a complex process.

Objective:

(1) To examine attractors to the athletic training profession and the high school setting, (2) to determine what, if any, differences exist between attractors to the profession and those to the high school setting, and (3) to identify whether differences in attractors can be attributed to sex, time of decision, or job status.

Design:

For this descriptive study, we designed the survey using the existing socialization literature. A pilot study was conducted and distributed by e-mail.

Setting:

Survey e-mailed to participants.

Patients or Other Participants:

High school ATs (n = 124) in South Carolina.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Overall mean scores for attractors to athletic training and to the high school setting were calculated. Overall mean scores were compared with individual attractor mean scores to determine the most influential attractors. Effect sizes were used to determine differences in sex, time of decision, and job status.

Results:

Of the total population of South Carolina high school ATs, 92 (74%) returned surveys. High school ATs in South Carolina had similar demographics with regard to age, sex, and race. Attractors to athletic training and to the high school setting were similar and included statements consistent with the continuation, service, and interpersonal themes identified in the existing socialization literature. We noted differences, however, between early and late deciders and between full-time and part-time ATs.

Conclusions:

The findings surrounding attractors to athletic training and the high school setting contribute to the existing socialization literature and help in our understanding of how and why individuals choose to become ATs and to work in the high school setting.

Keywords: socialization, occupational choice, attractors, secondary school athletic trainers

Key Points

For the survey participants, the most influential attractors to the athletic training profession were consistent with the continuation, service, and interpersonal themes.

Working with athletes, adults, and children, along with becoming a health care professional and teaching young people, are previously unidentified attractors to an athletic training career or the high school setting.

Part-time athletic trainers may view the high school setting differently than full-time athletic trainers do, depending on their career goals.

Late deciders were more likely than early deciders to become athletic trainers in preparation for another health care profession.

Women were more likely than men to be attracted to athletic training to become health care professionals, to spend additional time with family, and to consider the high school setting less demanding than other settings.

The number of employment opportunities for secondary school athletic trainers (ATs) has increased substantially in the past several years and will more than likely continue to grow in the future.1,2 Although no empirical evidence exists to explain this growth, it makes sense that advances in educational reform and increased awareness of the value of ATs by school districts and the general public could explain the past and future growth in the high school setting.1

As the number of ATs in the secondary school setting increases, so do the number of high school- and college-aged students who are being exposed to the athletic training profession in the high school setting. High school ATs are developing sports medicine curricula for high school students, and college students are gaining exposure to the high school setting through their clinical education. Now more than ever, ATs in these settings play a key role in the development and future of our profession, because they have the ability to influence students' perceptions of the profession and, ultimately, their career decisions.3 A clearer understanding of what attracts individuals to athletic training in general and to the high school setting in particular can help to provide insight into why so many individuals choose to be ATs in the high school setting.

Historically, career choice has been studied using a socialization framework.4 Only recently has socialization into the athletic training profession gained attention.3,5–17 Issues surrounding career choice,5 educational preparation,13 student retention,14 burnout,15,17 and role strain16 are among the most recent topics related to the socialization of athletic training students and current professionals. Findings in these areas are contributing to a greater understanding of how and why people choose to become ATs and the various obstacles students and professionals must overcome.

The process of socialization, often referred to as occupational socialization, has commonly been studied using a multistage approach. Researchers typically characterize socialization in 3 phases: anticipatory,4 professional,18 and organizational18 socialization. These 3 phases do not contain distinct transition points or definitive times at which all individuals move from one stage to another.

The first phase of occupational socialization, and the focus of our study, is anticipatory socialization. Anticipatory socialization, or recruitment, refers to the “process by which an individual adopts the values of a group to which he aspires but does not belong.”4(p265) The process of anticipatory socialization is complex, varies among individuals, and is influenced by a number of personal, situational, and societal factors.19 This is an important phase, because it is a time when individuals learn about and develop perceptions regarding the athletic training profession. It is also a time during which people can learn about and become attracted to a specific athletic training setting. For example, a high school student may become attracted to athletic training and develop perceptions about being a high school AT while taking a sports medicine class in high school or working with a high school AT. In contrast, a person who does not have an AT at his or her high school may learn about and become attracted to the high school setting only after completing clinical rotations in an athletic training education program.

Two important components of an individual's decision to choose a career include attractors (the many characteristics of a profession that compel the interest of recruits) and facilitators (the individuals and events that influence recruits' career decisions).20 A full understanding of attractors and facilitators is important for a variety of reasons. Understanding what attracts an individual to a profession helps to determine how an occupation “attempts to announce itself to potential recruits.”18(p6) A recruit's views of a profession ultimately describe the amount of prestige associated with the profession, self-image, and how he or she acts as a professional.19,21 Finally, a better understanding of what compels an individual to become an AT and the reasons for entering a specific work setting can assist in directing student recruitment efforts and can enhance the education of future professionals.

The works of Mensch et al8 and Mensch and Mitchell3 have provided much insight into how ATs are introduced to and either choose to become ATs or decide against a career in athletic training. Pitney9 examined how high school ATs are socialized into and learn to engage in the role of a high school AT. Mensch et al7 also explored the high school setting, focusing on the interactions between coaches and ATs. Still, the manner in which ATs are socialized into the profession, and particularly into the high school setting, is complex and many unknowns remain. No authors have examined specifically what attracts individuals to enter athletic training and which factors influence the decision to choose a specific athletic training setting (eg, high school, collegiate, or professional sport). Given the previously mentioned significance of understanding attractors and the recent attention to the high school setting, our study fills an important void in the existing athletic training socialization literature by providing an in-depth examination of the many factors that compel individuals to become ATs and to work in the high school setting. Specifically, our purposes were (1) to examine attractors to the athletic training profession and to the high school setting, (2) to determine what, if any, differences existed between attractors to athletic training in general and to the high school setting, and (3) to identify whether differences in attractors could be attributed to sex, time of decision (early versus late deciders), or job status (full-time versus part-time high school ATs).

METHODS

Participants

Telephone contact was made with a representative at each of the 270 public and private high schools in South Carolina to determine how many high school ATs were employed in the state. The resulting population and the target population for this study included 138 ATs located at 130 schools.

Instrument Design

No questionnaire existed that exclusively examined anticipatory socialization in athletic training. As a result, we constructed an original questionnaire for this descriptive study. The primary goal of the instrument was to examine attractors to the athletic training profession and the high school setting. The survey design included 3 steps: (1) review of literature, (2) content expert review, and (3) pilot study.

First, we developed a list of the major attractor themes from the socialization literature in medicine,22–25 teaching,20 physical education,18,19,26–32 physical therapy,33 and athletic training.3,8 From this, we completed an in-depth examination of the Dodds et al28 instrument. Dodds et al28 examined anticipatory socialization in various sport-related occupations, including athletic training. With permission, we adapted their Physical Education Majors Background Survey28 and specifically, the manner in which they examined attractors, to meet the particular needs of this study.

Next, 3 content experts examined the survey. The experts included individuals with more than 45 years of combined experience in higher education, including research backgrounds in the areas of physical education and athletic training socialization as well as extensive experience with research methods. The content experts examined the survey for overall content and clarity. They provided feedback regarding the extent to which the survey items were clear (to reduce the possibility that items could have different interpretations or meanings) and were appropriate for the intended population. Questions were edited according to their feedback and the major attractor themes for athletic training and the high school setting were developed.

The final step in the instrument design was completion of a pilot study, including 7 ATs (3 men, 4 women). Because high school AT job descriptions can vary greatly, the 7 ATs were purposefully selected to represent common high school AT profiles. This was done to ensure that the attractor statements and other closed-ended questions were appropriate for all types of high school ATs. Three individuals were currently employed as high school ATs. They included (1) a full-time high school AT with no teaching responsibilities, (2) a full-time high school AT and teacher who taught 3 classes at her high school, and (3) a clinic AT who provided athletic training services to a local high school. The remaining 4 had previous experience as high school ATs. They included a former graduate student who provided athletic training services to a high school in fulfillment of his graduate assistantship and former ATs who worked in hospitals or clinics (or both) and were outsourced to 1 or more high schools. Pilot study participants completed the survey via e-mail attachment and were asked to provide suggestions for improvement regarding clarity of instructions and questions. They also were asked to identify whether or not they had difficulty providing answers to any of the questions and whether the list of attractor statements represented their complete responses. Based on the results of the pilot study, 2 attractor statements for the high school setting were added to the survey: “Because the high school setting is less demanding than other settings” and “Because it is part of my job responsibilities.”

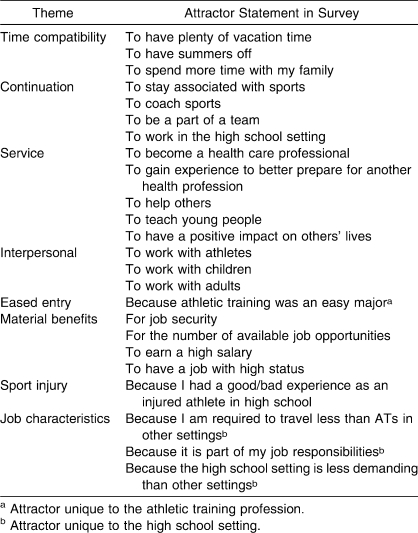

The final AT survey asked participants to provide demographic and background information and to indicate what attracted them to become an AT and to enter the high school setting. Attractor statements totaled 21 for the athletic training profession and 23 for the high school setting (Table 1). Demographic and background questions included age, sex, race, age at which career decision was made, and route to certification (grandfather clause, apprenticeship or internship route, or curriculum route). Participants also were asked to provide specific information about their jobs to determine job status (full-time or part-time high school AT).

Table 1.

Attractors to the Athletic Training Profession and to the High School Setting

Previous researchers in medicine,23–25 teaching,20 and physical education27–29,31,32 suggested that differences in attractors could be attributed to differences in sex and time of decision (early versus late decider). As a result, we also examined those variables, plus an additional variable (job status). Early and late deciders and full-time and part-time job status were operationally defined before the analyses were completed. An early decider25 was defined as any individual who made the decision to become an AT before or during high school and was 18 years of age or younger. A late decider25 was defined as any individual who decided at age 20 or older to pursue athletic training. Those individuals who were in college and between the ages of 18 and 20 years were neither early nor late deciders. Full-time status and part-time status were operationally defined in the following manner. An AT was considered full time if he or she provided coverage to only 1 high school and had no additional responsibilities in a hospital or clinic or as a graduate assistant. Full-time ATs included those individuals who taught classes or were administrators at their schools. Part-time ATs included individuals who provided coverage to more than 1 high school or to 1 high school but on an “as-needed” basis or had responsibilities in a hospital or clinic or as a graduate assistant.

Data Analysis

All attractor statements were examined using a 4-point Likert scale (no influence, little influence, moderate influence, major influence) to determine the extent to which each item influenced a participant's decision to become an AT and to work in the high school setting. For this descriptive study, the primary data analysis included calculating mean scores for each of the 21 attractors to the athletic training profession and for the 23 attractors to the high school setting. An overall mean for attractors to the athletic training profession and to the high school setting was calculated also. The overall attractor mean (mean2) was compared with individual attractor means (mean1), and the difference (D) was calculated to determine the most influential attractors to the athletic training profession and the high school setting.

Effect sizes (ESs) are a useful way to examine the meaningfulness or the difference between 2 means34 and were calculated to determine the degree to which sex, time of decision (early versus late decider), and job status (full time versus part time) influenced patterns in attractors. The following formula was used: ES = (mean1 − mean2)/sp, where the pooled

According to Thomas et al,34 an ES of 0.8 or greater is large, 0.5 is moderate, and 0.2 or less is small. For the purposes of this descriptive study, ESs equal to or greater than 0.5 (moderate) were investigated and discussed.

RESULTS

A total of 138 high school ATs in South Carolina were identified as potential participants for this study. Initial consent was obtained via telephone from 124 of the 138 ATs. Several attempts were made to contact the remaining 14 ATs but were unsuccessful. The survey was distributed to each of the 124 ATs by e-mail attachment. Participants completed the survey and e-mailed it back as an attachment. Individuals who had difficulty returning the survey via e-mail printed the survey, completed it by hand, and returned it by mail. Follow-up correspondence was sent to those who did not respond within 7 to 10 days. Of the 124 surveys sent, a total of 93 were returned. One was eliminated because the vast majority of that survey was incomplete. The remaining 92 surveys contributed to the response rate, which was 74%. This response rate represented 67% (92/138) of the total population of high school ATs in South Carolina.

The results are organized in the following sections and include participants' backgrounds, attractors to the athletic training profession, and attractors to the high school setting. Results surrounding attractors to the athletic training profession and the high school setting include an examination of differences found in job status, sex, and time of decision.

Participants' Backgrounds

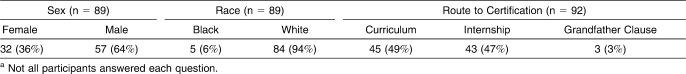

Participants were asked to report their age, sex, race, and the route by which they became eligible for the Board of Certification examination. One participant did not report age. The remaining participants' (n = 91) ages ranged from 22 to 60 years old (mean = 32.9 ± 8.89 years). Sex, race, and route to certification are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Survey Participants' Sex, Race, and Route to Certificationa

Attractors to the Athletic Training Profession

Attractors were rated using a 4-point Likert scale (no influence, little influence, moderate influence, and major influence). Eight attractors to the athletic training profession had mean scores higher than the overall attractor mean (mean = 2.27): to help others (mean = 3.74, difference = 1.47), to work with athletes (mean = 3.73, difference = 1.46), to stay associated with sports (mean = 3.60, difference = 1.33), to have a positive impact on others' lives (mean = 3.48, difference = 1.21), to become a health care professional (mean = 3.22, difference = 0.95), to teach young people (mean = 2.78, difference = 0.51), to be a part of a team (mean = 2.60, difference = 0.33), and to work with children (mean = 2.30, difference = 0.03).

In summary, the most influential attractors to the athletic training profession were consistent with the following themes: continuation (to stay associated with sports and to be a part of a team), service (to help others, to become a health care professional, to have a positive impact on others' lives, and to teach young people), and interpersonal (to work with athletes and to work with children).

Differences in Job Status

Full-time ATs totaled 52 (57%) and part-time ATs, 40 (43%). The part-time ATs included individuals who worked at a clinic (n = 13), hospital (n = 9), or as a graduate assistant (n = 10) and those who worked only in the high school setting but split their time among multiple schools or provided limited coverage to 1 high school (n = 8).

Only 1 attractor, to work in the high school setting, had a moderate ES (0.60), indicating that full-time ATs were more likely to be attracted to a career in athletic training to work in the high school setting. The remaining attractors had ESs below 0.5 and did not indicate meaningful differences between full-time and part-time ATs.

Differences in Sex

Females were more likely to be attracted to a career in athletic training to become a health care professional (ES = 0.65) and to spend more time with family (ES = 0.52). The remaining attractors had ESs below 0.5 and did not indicate meaningful differences between female and male ATs.

Differences in Time of Decision

Participants in this study became interested in athletic training between the ages of 12 and 33 years (mean = 17.72 ± 3.65 years) and made the definite decision to become an athletic trainer between the ages of 15 and 37 years (mean = 19.65 ± 3.52 years). Early deciders totaled 31 and late deciders, 34; the remaining 27 participants were neither early nor late deciders. Females accounted for 45% of early deciders (n = 14) and males, 55% (n = 17). However, only 32% of late deciders were women (n = 11), and 68% were men (n = 23).

Late deciders were more likely to be attracted to a career in athletic training to gain experience to better prepare for another health care profession (ES = 0.68). The remaining attractors had ESs below 0.5 and did not indicate meaningful differences between early and late decider ATs.

Attractors to the High School Setting

Ten attractors to the high school setting had mean scores higher than the overall attractor mean (mean = 2.15): to help others (mean = 3.42, difference = 1.27), to have a positive impact on others' lives (mean = 3.39, difference = 1.24), to work with athletes (mean = 3.36, difference = 1.21), to stay associated with sports (mean = 2.99, difference = 0.84), to become a health care professional (mean = 2.95, difference = 0.80), to teach young people (mean = 2.84, difference = 0.69), because it is part of my job responsibilities (mean = 2.74, difference = 0.59), to work in the high school setting (mean = 2.52, difference = 0.37), to be a part of a team (mean = 2.38, difference = 0.23), and to work with children (mean = 2.23, difference = 0.08).

Differences in Job Status

Full-time ATs were more likely to be attracted to be a high school AT for 10 reasons: to stay associated with sports (ES = 0.57), to be a part of a team (ES = 0.51), to work in the high school setting (ES = 0.83), to help others (ES = 0.53), to teach young people (ES = 0.62), to have a positive impact on others' lives (ES = 0.54), to work with athletes (ES = 0.64), to work with children (ES = 0.57), for job security (ES = 0.58), and to have a job with high status (ES = 0.52). In contrast, part-time ATs were more likely to be at high schools as part of their job responsibilities (ES = −1.06). The remaining attractors had ESs below 0.5 and did not indicate meaningful differences between full-time and part-time ATs.

Differences in Sex

Female ATs were more likely to be high school ATs because the high school setting is less demanding (ES = 0.67). The remaining attractors had ESs below 0.5 and did not indicate meaningful differences between male and female ATs.

Differences in Time of Decision

Late deciders were more likely to be high school ATs to coach sports (ES = 0.52). The remaining attractors had ESs below 0.5 and did not indicate meaningful differences between early and late decider ATs.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of our study was (1) to examine attractors to the athletic training profession and to the high school setting, (2) to determine what, if any, differences existed between athletic training in general and the high school setting in particular, and (3) to identify whether differences in attractors could be attributed to sex, time of decision, or job status. Examining attractors to the athletic training profession and the high school setting yielded numerous findings. The significance of the results and their relation to existing socialization and other pertinent literature will be discussed in the following section.

Backgrounds of High School ATs

The findings of our study as they relate to attractors to athletic training and to the high school setting should be interpreted with an understanding for the participants' demographics. High school ATs in South Carolina had similar backgrounds in regard to age, race, and sex. Most participants were between the ages of 22 and 39 years (77%), white (94%), and men (64%). These findings are consistent with the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) membership statistics for race but not for sex. In fact, according to the NATA,2 male and female ATs are represented equally (50% men, 50% women) in the overall AT population. With regard to race, the only other population represented in this study was black (6%). This value appears to be slightly higher than the 2% seen in the overall NATA membership2 but is consistent with the fact that blacks and other minorities are underrepresented in the athletic training profession.

It is interesting that ATs in the current study represented almost equally the internship (50%) and curriculum (49%) routes to certification. This finding is likely to change in 5 to 10 years, because the internship route to certification was abolished in 2004.

Attractors to the Profession and to the High School Setting

We examined a variety of attractors in this study and identified 3 themes, consistent with Lortie's20 early work on socialization, as attractors to both the athletic training profession and to the high school setting. These three themes were interpersonal, service, and continuation concerns. The first 2 suggest that ATs were attracted to athletic training and to the high school setting because they enjoy working with athletes and children (interpersonal) and view the profession as an opportunity to become a health care professional, to help others, to have a positive impact on others' lives, and to teach young people (service). The last theme, continuation, is the idea that an individual is attracted to the athletic training profession to be a part of a team and to remain associated with sports.

Similar to the findings of Mensch and Mitchell,3 participants in the current study were attracted to a career in athletic training because they enjoyed helping others, wanted to remain associated with sports, and desired to be a part of a team. However, the remaining attractors—to work with athletes, to work with adults, to work with children, to become a health care professional, and to teach young people—had not been identified previously in the literature as attractors to a career in athletic training or to the high school setting and, therefore, are new findings in the athletic training literature.

Schrader35 argued that ATs are in an identity crisis. He described “two distinct and conflicting ideas about who we are/should be as a profession”35(p17): the AT health care provider and the AT team member. Just as participants in Mensch and Mitchell's3 study aligned with the team member model, ATs in the current study were attracted to the athletic training profession and to the high school setting to remain associated with sports and to be a part of a team. However, our participants were attracted to athletic training and to the high school setting to help people and to become health care professionals, suggesting that they also strongly aligned with the health care model. Thus, our results differ from the findings of Mensch and Mitchell3 and suggest that the health care professional and team member models do exist. This is an important finding, which raises the question of how high school ATs in the current study navigated the challenges surrounding the conflicting health care provider and team member views. The literature in physical education18 and Pitney's10 work in athletic training suggest a variety of factors that could influence how individuals act in their professional roles, including relationships with institutions and previous educational or work experiences.

The desire to teach young people as an attractor to become an AT initially may be somewhat surprising, considering that teaching and athletic training are different professions. However, athletic training education programs traditionally have been and commonly still are housed in departments with physical education. Subsequently, schools have offered dual degrees in athletic training and physical education teaching. In fact, from the 1950s until approximately 1980, athletic training students were required to fulfill the requirements for a secondary-level teaching certification as part of their degree program.36 The ATs in our study were not only attracted to athletic training and to the high school setting to teach, but 40 of 52 (77%) of the full-time ATs reported that they did teach at their high schools. Two additional full-time ATs reported being teaching or instructional aides.

Comparing the findings of the current study with those of other sport-related and health care professions yields many similarities. Interpersonal, service, and continuation themes have been well supported in the physical education teaching and coaching literature.19,26–31,37 As discussed previously, the basis for our study was derived largely from the literature in physical education. This is because physical education, like athletic training, is a sport-related occupation and because the current literature is lacking in describing attractors in other health care professions similar to athletic training (namely, physical therapy). In fact, no authors have exclusively examined attractors to physical therapy, and only 2 groups33,38 have discussed results related to attractors. Students indicated that they became interested in a career in physical therapy due to their previous involvement in sport33 and their desire to help others.33,38 As Lortie20(p25) stated, “Occupations compete, consciously or not, for members, and there is a largely silent struggle between occupations as individuals choose among alternative lines of work.” With so many occupations to choose from and similar characteristics among the many available professions, our findings suggest a need to understand why individuals ultimately commit to a career in athletic training. In turn, we can better understand how the athletic training profession is viewed in comparison with other sport-related and health care occupations.

Differences in Job Status and Time of Decision

Lortie20 suggested that the wide decision range, or the various ages at which individuals make career decisions, helps to broaden the numbers and backgrounds of future professionals. Examining findings specific to job status and time of decision yielded several important points. First, in contrast to early deciders, late deciders were more likely to be ATs to gain experience as preparation for another health profession. Second, full-time ATs were more likely to be high school ATs for continuation (ie, to stay associated with sports, to be a part of a team), service (ie, to help others, to have a positive impact on others' lives, to teach young people), and interpersonal reasons (eg, to work with athletes and children). Full-time ATs were also more likely to be high school ATs for an additional reason: material benefits (eg, job security and a job with high status). Material benefits, as first identified by Lortie,20 have been influential for recruits from several professions, including athletic training.27,28 In contrast to full-time ATs, part-time ATs in the current study (ie, clinic or hospital ATs and graduate assistants) were more likely to be high school ATs because it was part of their job responsibilities.

These findings suggest the notion of a career contingency.18 The fact that late deciders were more likely to become ATs to better prepare them for another allied health profession suggests their primary motive for choosing athletic training may not have been to become a member of the athletic training profession. Rather, what they desired (to enter another allied health profession, such as physical therapy, nursing, or medicine) may be dependent, or contingent, upon their willingness to complete an undergraduate program that fulfills the prerequisites for further schooling. As a result, late deciders may view their roles as future members of the athletic training profession differently than early deciders do.

Furthermore, the fact that part-time individuals were high school ATs due to their job responsibilities suggests their primary motive may or may not have been to work in the high school setting. For some, the dual position may have been attractive. In other instances, what part-time ATs want to do (eg, be a clinic or hospital AT or earn a graduate degree) may depend upon their willingness to work in the high school setting. As a result, part-time ATs may view the high school setting and, subsequently, their other roles (eg, clinic or hospital AT or graduate assistant) differently than full-time ATs do. Coaches and administrators may view part-time high school ATs differently from those who are full time. As Mensch et al7 stated, when coaches have a lack of exposure to part-time ATs, both parties are at an immediate disadvantage. Coaches are unaware of the many services ATs can provide and, therefore, are unable to fully capitalize on ATs' knowledge and skills. Part-time ATs are not as visible as full-time ATs and thus are unable to establish clear lines of communication with coaches and administrators.7 As a result, the extent to which quality health care is delivered to patients may vary. Future research is needed in this area to better understand how differences in job status translate to practice (the extent to which quality health care is delivered) and the perceptions of ATs developed by coaches, patients, administrators, and the general public.

Differences in Sex

We noted 3 sex differences in the current study. First, women were more likely than men to be attracted to athletic training to become health care professionals. This finding is best explained by understanding the previously discussed service theme and the sex distribution of other health professions similar to athletic training, specifically occupational and physical therapy. According to the US Department of Labor,39 the occupational and physical therapy professions are largely composed of women: 86% and 68%, respectively. Thus, it was not surprising that women in the current study more frequently reported the desire to become ATs for the opportunity to provide a health care service to society.

Another sex difference was that women were more attracted to careers in athletic training to spend additional time with family. This was not expected to be an attractor to the profession of athletic training, because ATs typically work during nontraditional hours and often have extensive travel requirements on weekends and during holidays. However, this finding is significant in suggesting that at some point in their career decision-making process, women in the current study developed the perception that athletic training is a profession that allows for spending time with family. How, why, and under what circumstances this perception was developed was not examined but should be addressed by future researchers to provide greater context to the process of career decision making.

The additional finding related to sex differences is that women were more attracted to the high school setting because it was less demanding than other settings. The context in which women viewed the high school setting as less demanding is unknown, and without additional supporting data, it is impossible to provide a concrete rationale for this finding. High school ATs' job descriptions and requirements vary according to a number of confounding variables, including the school district in which the athletic trainer is employed, the number of ATs at each high school, the size of the high school, and the number of sports teams at the high school, to name a few. However, when compared with other athletic training employment settings, it could be argued that the high school setting requires less extensive travel than the professional sport setting, for example.

IMPLICATIONS

Although several implications can be drawn from the results of this study, the extent to which these implications can be generalized to the entire athletic training population is limited. We examined only high school ATs in the state of South Carolina. This included individuals who were full-time ATs as well as those who worked in a sports medicine clinic or hospital during the morning and early afternoon hours and then provided part-time athletic training services to a high school. These ATs were chosen purposefully for their proximity to the researchers and because they represented a range of profiles of professionals working in high school settings. As a result, this descriptive study includes a nonrandom sample. The ability to generalize the results and implications of the findings to other states and other settings, such as colleges or universities, is limited. Readers should consider how our findings may relate to their specific locations, settings, and conditions.

Examining attractors is one way to help explain the perceptions individuals have developed regarding athletic training and the high school setting. As the athletic training profession in general and in the high school setting in particular continues to grow, individuals' exposure to high school ATs cannot be underestimated. It is during the high school years that young people are often first exposed to ATs and develop perceptions about the demands and specific tasks of both the profession in general and the high school setting in particular. High school ATs must assist young individuals in developing accurate perceptions through sports medicine classes and by allowing students to become involved in their everyday operations. Without accurate perceptions, individuals are likely to be unsatisfied, change jobs, or leave the profession entirely.

Attractors also help us to better understand the reasons people choose to enter a particular setting. Without knowledge of an athletic training employment setting, a student will be unable to develop perceptions for the setting and, therefore, will be unable to make well-informed career decisions. Athletic training education program faculty and staff need to understand the complexity of the career decision-making process when deciding where and when students complete clinical experiences and the extent to which students are exposed to a variety of employment settings during their preprofessional years. For example, students who were not exposed to an AT in high school must gain exposure to the high school setting, either as part of their educational program requirements or during a volunteer, internship, or assistantship opportunity outside the didactic and clinical program.

FUTURE RESEARCH

The intention of our descriptive study was to examine attractors for athletic training and for the high school setting. The findings contribute to the existing socialization literature and enhance our understanding of the larger process of socialization into athletic training. Of additional importance was the creation of a framework on which future studies can be modeled and that contributes to a greater understanding of how and why individuals become ATs and choose to work in the high school setting.

The high school setting is only one athletic training employment setting among many. Further investigation is needed to examine what, if any, patterns exist among attractors for other settings (eg, college and professional sport) within the overall AT population. Are ATs in other settings attracted to athletic training, and with regard to their setting, for the same or different reasons than participants in this study? If differences are noted within and among the various employment settings, identifying the implications of these differences is important for how we function as a profession and how we are viewed by the public in general and specifically by other allied health professionals.

Based on the differences noted between full-time and part-time ATs, early and late deciders, and male and female ATs, further research is needed to examine how differences translate into individuals' actions. In other words, do high school ATs possess custodial (resistant to change) or innovative orientations toward the high school setting? From this information, the implications for these actions can be determined. The extent to which orientations remain the same or change throughout occupational socialization is also important and should be examined.18

Footnotes

Alison Gardiner-Shires, PhD, ATC, contributed to conception and design; acquisition and analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the article. James Mensch, PhD, ATC, contributed to conception and design; analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunt V. Eye on the high school setting. NATA News. December 2004. pp. 13–15.

- 2.National Athletic Trainers' Association. Membership statistics. http://www.nata.org/members1/documents/MembStats/2006eoy.htm. Accessed June 1, 2007.

- 3.Mensch J, Mitchell M. Attractors to and barriers to a career in athletic training: exploring the perceptions of potential recruits [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl):S21. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merton R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure. Rev ed. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1957. pp. 264–266. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fergusson D.S, Doherty-Restrepo J.L, Odai M.L, Tripp B.L, Cleary M.A. High school experiences influence selection of athletic training as a career [abstract] J Athl Train. 2007;42(suppl):S70–S71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klossner J.T. The role of legitimation in the professional socialization of second-year athletic training students in a CAAHEP-accredited program [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl):S21. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mensch J, Crews C, Mitchell M. Competing perspectives during organizational socialization on the role of certified athletic trainers in high school settings. J Athl Train. 2005;40(4):333–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mensch J, Rodger M, Mitchell M. Exploring the subjective warrants of potential athletic training recruits [abstract] J Athl Train. 2004;39(suppl):S12–S13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitney W.A. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in high school settings: a grounded theory investigation. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitney W.A. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitney W.A, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens S.W, Perrin D.H, Schmitz R.J, Henning J.M. Clinical experience's role in professional socialization as perceived by entry-level athletic trainers [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl):S22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klossner J.C. The influence of meaningful experiential learning on the professional socialization of second-year athletic training students: a theoretical model [abstract] J Athl Train. 2007;42(suppl):S69–S70. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodge T.M, Mitchell M.F, Mensch J.M. Student retention in athletic training education programs [abstract] J Athl Train. 2007;42(suppl):S71. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riter T.S, Kaiser D.A, Hopkins J.T, Pennington T.R, Chamberlain R, Eggett D. Presence of burnout in undergraduate athletic training students [abstract] J Athl Train. 2007;42(suppl):S71–S72. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charles-Liscombe R.S, Perrin D.H. Academic role orientation and incongruency increases athletic training educators' role strain [abstract] J Athl Train. 2007;42(suppl):S72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter J.M, Van Lunen B.L, Walker S, Ismaeli Z, Onate J.A. An assessment of burnout in undergraduate athletic training education program directors [abstract] J Athl Train. 2007;42(suppl):S72. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawson H.A. Toward a model of teacher socialization in physical education: the subjective warrant, recruitment, and teacher education (part 1) J Teach Phys Educ. 1983;2(3):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewar A.M, Lawson H.A. The subjective warrant and recruitment into physical education. Quest. 1984;36(1):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lortie D.C. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1975. pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Western J.S, Anderson D.S. Education and professional socialization. J Sociol. 1968;4(2):91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merton R.K, Reader G.G, Kendall P.L, editors. The Student Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957. pp. 3–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helfrich M.L. Paths into professional school: a research note. Work Occup. 1975;2(2):169–181. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogoff N. The decision to study medicine. In: Merton R.K, Reader G.G, Kendall P.L, editors. The Student Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957. pp. 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thielens W., Jr . Some comparisons of entrants to medical and law school. In: Merton R.K, Reader G.G, Kendall P.L, editors. The Student Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957. pp. 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Templin T.J, Woodford R, Mulling C. On becoming a physical educator: occupational choice and the anticipatory socialization process. Quest. 1982;34(2):119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belka D.E, Lawson H.A, Lipnickey S.C. An exploratory study of undergraduate recruitment into several major programs at one university. J Teach Phys Educ. 1991;10(3):286–306. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodds P, Placek J.H, Doolittle S.A, Pinkham K.M, Ratliffe T.A, Portman P.A. Teacher/coach recruits: background profiles, occupational decision factors, and comparisons with recruits into other physical education occupations. J Teach Phys Educ. 1992;11(2):161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchinson G.E, Buschner C.A. Delayed-entry undergraduates in physical education teacher education: examining life experiences and career choice. J Teach Phys Educ. 1996;15(2):205–223. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pooley J.C. The Professional Socialization of Physical Education Students in the United States and England [dissertation] Madison: University of Wisconsin; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sage G.H. Becoming a high school coach: from playing sports to coaching. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1989;60(1):81–92. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1989.10607417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hutchinson G.E. Prospective teachers' perspectives on teaching physical education: an interview study on the recruitment phase of teacher socialization. J Teach Phys Educ. 1993;12(4):344–354. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore V, Beitman L, Rajan S, et al. Comparison of recruitment, selection, and retention factors: students from under-represented and predominately represented backgrounds seeking careers in physical therapy. J Phys Ther Educ. 2003;17(2):56–66. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas J.R, Nelson J.K, Silverman S.J, editors. Research Methods in Physical Activity. 5th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2005. pp. 115–116. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrader J. We have found the enemy, and it is us. NATA News. April 2005. pp. 16–17.

- 36.Delforge G.D, Behnke R.S. The history and evolution of athletic training education in the United States. J Athl Train. 1999;34(1):53–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Placek J.H, Dodds P, Doolittle S.A, Portman P.A, Ratliffe T.A, Pinkham K.M. Teaching recruits' physical education backgrounds and beliefs about purposes for their subject matter. J Teach Phys Educ. 1995;14(3):246–261. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown-West A.P. Influencers of career choice among allied health students. J Appl Health. 1991;20(3):181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Department of Labor. Employment by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. http://www.bls.gov/cps/#tables. Accessed March 1, 2008.