Abstract

Live-vaccine delivery systems expressing two model antigens from Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, F2P97 (Adh) and NrdF, were constructed using Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA (STM-1), and immunogenicity in mice was evaluated. Recombinant plasmid-based expression (PBE) and chromosomally based expression (CBE) systems were constructed. The PBE system was formed by cloning both antigen genes into pJLA507 to create an operon downstream of temperature-inducible promoters. Constitutive CBE was achieved using a promoter-trapping technique whereby the promoterless operon was stably integrated into the chromosome of STM-1, and the expression of antigens was assessed. The chromosomal position of the operon was mapped in four clones. Inducible CBE was obtained by using the in vivo-induced sspA promoter and recombining the expression construct into aroD. Dual expression of the antigens was detected in all systems, with PBE producing much larger quantities of both antigens. The stability of antigen expression after in vivo passage was 100% for all CBE strains recovered. PBE and CBE strains were selected for comparison in a vaccination trial. The vaccine strains were delivered orally into mice, and significant systemic immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG responses against both antigens were detected among all CBE groups. No significant immune response was detected using PBE strains. Expression of recombinant antigens in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA from chromosomally located strong promoters without the use of antibiotic resistance markers is a reliable and effective method of inducing a significant immune response.

The use of live, attenuated bacteria as vaccine delivery systems for heterologous antigens has been extensively studied. In particular, attenuated Salmonella strains have been modified to express a wide range of antigens from bacterial, parasitic, and viral sources (reviewed in references 20, 29, and 41). After oral administration, Salmonella can penetrate the Peyer's patches via M cells and colonize the mesenteric lymph nodes, which contain various antigen-presenting cells (reviewed in reference 5). This can generate a range of immune responses, including systemic and mucosal responses at local and distal sites. Other advantages of using attenuated Salmonella include the ease of oral administration, which bypasses the need for needle administration; increased antigen presentation due to the use of a live-vector delivery system, the induction of both Th1 and Th2 immune responses; and the wide range of attenuated Salmonella and recombinant vectors available to researchers (19, 20, 51).

However, there are a number of issues to overcome. Most methods for the expression of heterologous antigens in Salmonella use plasmids to express the antigenic proteins. This can have several drawbacks. The stable maintenance of the expression plasmid in vivo can be difficult to achieve. Tightly regulated promoters are often used to increase plasmid stability, and several in vivo-inducible promoters have delivered promising results. Oral delivery of aroAD-attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium expressing the C fragment of tetanus toxin from nirBp was able to protect mice from lethal tetanus challenge (6). Other in vivo-inducible promoters, such as pagCp, sspAp, and ssaGp, have also been used in aroAD-attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium to generate tetanus toxoid-specific and heat-labile toxin B immune responses in mice (12, 35, 48).

Instability may arise through the extra metabolic burden associated with a high-copy-number plasmid, leading to the selection of variants that have lost the plasmid during growth. In vitro, plasmids can be maintained through the use of antibiotic resistance markers; however, this is not feasible under field conditions, with emerging antibiotic resistance a global health issue. In order for these vaccines to be used in a commercial human or veterinary setting, the antibiotic resistance genes must be removed, although a selection mechanism for the maintenance of plasmids during vaccine production would still be required (48). One method for nonantibiotic maintenance of plasmid vectors is the use of the asd vector/Δasd host lethality system, in which the attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium has an obligatory requirement for diaminopimelic acid that is complemented by the vector (39). Non-antibiotic resistance markers have also been developed, including bar, which encodes resistance to the herbicide dl-phosphinothricin (38); merA, which provides resistance to organomercurial compounds (21); and arsAB, which express arsenite resistance proteins (9). Plasmid-based expression (PBE) systems can express antigens at high levels; however, high levels of expression of some antigens can have a growth-inhibitory effect (10, 51) and thus can reduce the efficacy of the live delivery system.

To overcome some of the problems associated with PBE systems, heterologous antigen expression cassettes have been integrated into the Salmonella chromosome (25, 47). The chromosomally integrated constructs have been examined as vaccines in several studies and were shown to elicit a protective immune response, although generally the level of antigen expression is much lower than in plasmid-based systems (20).

In this study, we used two Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae antigens, F2P97 (hereafter referred to as Adh) and ribonucleotide reductase (NrdF), in a screen to identify novel promoters useful for antigen expression in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium from single-copy chromosomal constructs. M. hyopneumoniae is a pathogen of swine that colonizes the ciliated epithelial cells of the respiratory tract and causes significant economic losses (11). Adh and NrdF have both been previously studied in vaccination experiments when expressed from plasmid-based systems in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA (7, 8, 15, 16, 17). Oral vaccination with NrdF-expressing S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA has resulted in significant immunoglobulin A (IgA) responses in murine lungs (16), increased murine splenocyte NrdF-specific gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production (7), and primed the porcine respiratory tract for an NrdF-specific secretory IgA response (17). Adh-stimulated splenocytes from mice orally vaccinated with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA expressing Adh showed increased IFN-γ production (8). The constructs generated in this study, which expressed both antigens in tandem, were used to orally vaccinate mice, and the immune responses were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of bacterial strains and isolation of genomic and plasmid DNA.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. M. hyopneumoniae was grown in Friis medium as previously described (18). Escherichia coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with antibiotics, where appropriate, at 37°C. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; rifampin (rifampicin), 100 μg/ml; and streptomycin, 100 μg/ml. Growth curve analysis with minimal medium supplemented with aromix was performed as previously described (33).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain/plasmid | Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | endA1 recA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) relA1 supE44 Δ(lac-proAB) [F′ traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15] | 52 |

| M15(pREP4) | Derivative of E. coli K-12; contains kanamycin-resistant pREP4, ensuring the production of high levels of lac repressor protein | Qiagen |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | ||

| STM-1 | aroA-attenuated strain | 1 |

| JA08 | Laboratory-passaged STM-1 strain; streptomycin sensitive, rifampin resistant | 48 |

| STM-AN1 | Chromosomal insertion of the nrdF-adh operon into dps of STM-1 | This study |

| STM-AN2 | Chromosomal insertion of the nrdF-adh operon into glgP of STM-1 | This study |

| STM-AN3 | Chromosomal insertion of the nrdF-adh operon into orf1 of STM-1 | This study |

| STM-AN4 | Chromosomal insertion of the nrdF-adh operon into traI of STM-1 | This study |

| STM-sspA | Chromosomal insertion of the nrdF-adh operon with sspAp into aroD of JA08 | This study |

| M. hyopneumoniae J | Laboratory-passaged nonvirulent strain | 44 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJLA506 | Ampicillin-resistant expression vector containing PLPR promoters and atpE ribosome binding sites | 45 |

| pJLA507 | pJLA506 with an XhoI-NcoI-EcoRI polylinker inserted into the EcoRI site | This study |

| pJLA507-A | pJLA507 with M. hyopneumoniae adh gene cloned between NdeI and SalI sites | This study |

| pJLA507-N | pJLA507 with M. hyopneumoniae nrdF gene cloned between NdeI and SalI sites | This study |

| pJLA507-AN | pJLA507-N with M. hyopneumoniae adh gene cloned into SalI site | This study |

| pUC18-NotI | Identical to pUC18 but with NotI-EcoRI-SalI-HindIII-NotI as multiple-cloning site | 24 |

| pUC18-AN | pUC18-NotI with promoterless nrdF-adh operon cloned into NotI | This study |

| pUT/Ars | Apr; Tn5-based delivery plasmid with arsA and arsB | 24 |

| pArs-AN | pUT/Ars with promoterless nrdF-adh operon cloned into NotI site | This study |

| pKKsspATetC | sspA promoter cloned into pKK233-2 | 48 |

| pKKsspA-AN | pKKsspA with nrdF-adh operon cloned between NcoI/HindIII sites | This study |

| pCVDaroDins | pCVD442 with 5′ and 3′ sections of S. enterica aroD | 48 |

| pCVD-AN | pCVDaroDins with sspAp-nrdF-adh-rrnBt cassette cloned into SphI and SacI | This study |

| pF2P97 | His-tagged F2P97 expression vector based on pQE9 | 27 |

| pKF1 | His-tagged NrdF expression vector based on pQE9 | 16 |

Plasmid DNA was isolated using the Wizard Plus SV Miniprep kit (Promega, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Isolation of genomic DNA was achieved using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For protein expression, His6-tagged Adh (27) and NrdF (16) expression vectors were used. E. coli cultures were grown to an optical density at 560 nm (OD560) of 0.8 at 37°C, induced with isopropyl thiogalactopyranoside at a final concentration of 1 mM, and grown for a further 4 h. The cells were pelleted at 5,000 × g for 10 min, and the recombinant protein was purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen) as specified in the manufacturer's instructions.

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

Restriction enzyme digestions and DNA ligations were performed according to standard procedures (43). To construct pJLA507-AN, nrdF was PCR amplified from M. hyopneumoniae strain J DNA using the primers 5′-GGCATATGGATCTATTATATAAACTAATT-3′ and 5′-GGGTCGACTTAAAACTCCCAATCTTCATG-3′. This PCR product encompassed the DNA encoding the 11-kDa carboxy terminus of NrdF. The adh gene was PCR amplified from M. hyopneumoniae strain J DNA using the primers 5′-GGCATATGAAATTAGACGATAATCTTCAG-3′ and 5′-GGGTCGACTTAAGGATCACCGGATTTTGAA-3′. This PCR product encompassed the DNA encoding an approximately 36-kDa segment of P97 incorporating both C-terminal repeat regions and is referred to as Adh. The PCR products and pJLA507 were digested with NdeI and SalI, ligated, and transformed into E. coli JM109. Potential clones were screened using digoxigenin (Dig)-labeled probes in a colony hybridization screening procedure according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, Australia). Plasmid pJLA507-A was then digested with XhoI and SalI to release the adh gene, which was then subcloned into the SalI site of pJLA507-N to yield pJLA507-AN. To construct pARS-AN, pJLA507-AN was digested with EcoRI and HindIII to release the nrdF-adh operon, which was then subcloned into pUC18NotI to create pUC18NotI-AN. Plasmid pUC18NotI-AN was digested with NotI, and the nrdF-adh operon was cloned into the NotI site of pUT/Ars (24) to form pARS-AN and subsequently transformed into E. coli CC118 λpir (Fig. 1).

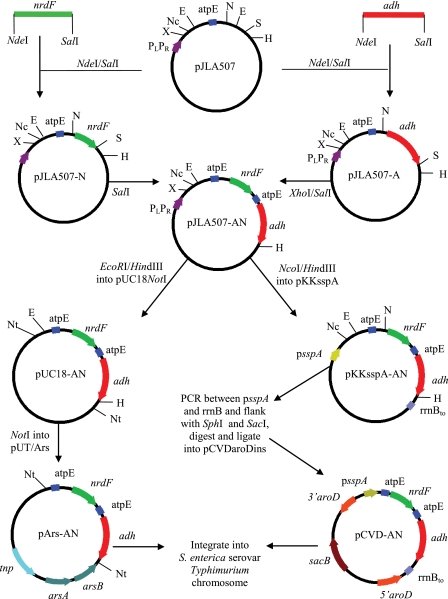

FIG. 1.

Cloning schematic for the production of PBE and CBE constructs. E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; N, NdeI; Nc, NcoI; Nt, NotI; S, SalI; X, XhoI; atpE, atpE ribosome binding site; rrnBto, E. coli rRNA terminator; tnp, transposase. The diagram is not to scale.

Construction of the sspA chromosomal expression strain began with digesting pJLA507-AN with NcoI and HindIII and then subcloning the promoterless nrdF-adh operon into the NcoI and HindIII sites of pKKsspATetC to form pKKsspA-AN. The region from sspAp to the rrnB terminator sequence (including the nrdF-adh operon) was PCR amplified using primers 5′-GTCGAAAGCTTGTCGACTTAAGGA-3′ and 5′-GACTCCCATGGATCTATTATATAAACT-3′. pCVDaroDins was digested with SphI and SacI, and the PCR product was ligated into these sites to form pCVD-AN.

PCR amplification of the nrdF-adh operon for screening purposes was performed using 5′-GGCATATGGATCTATTATATAAACTAATT-3′ and 5′-GGGTCGACTTAAGGATCACCGGATTTTGAA-3′.

Conjugation and arsenic resistance screening.

pARS-AN was transformed into E. coli SM10 λpir. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium STM-1 was mated with SM10 λpir(pARS-AN) overnight on LB agar at 37°C. Prior to being plated onto selective arsenite [As(III)] medium, the mating mixture was subjected to phosphate starvation. This was achieved by growing the mating mixture for 24 h with shaking at 37°C in 200 ml of minimal phosphate buffer (50 mM MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid], 50 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 0.8 mM CaCl2, 0.3 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 g/liter sodium citrate, 1 g/liter [NH4]2SO4, 36 μM FeSO4). As(III)-resistant colonies were then selected on LB agar plates supplemented with streptomycin, 100 μM 2,2′ bipyridyl, and 2 mM As(III) for 96 h at 37°C. To discriminate between genuine transposition events and illegitimate recombination events, arsenite-resistant colonies were screened for the loss of the ampicillin resistance marker by examining sensitivity to ampicillin.

Conjugation of pCVD-AN into S. enterica serovar Typhimurium JA08 (a rifampin-resistant, streptomycin-sensitive derivative of STM-1) was performed as previously described (48). Selection for double crossovers using lacZ color selection was performed as previously described (48). The double crossovers were confirmed via PCR, and the double-crossover strain was designated STM-sspA.

Colony immunoblotting screening for antigen expression.

Colony immunoblotting was performed essentially as previously described (43). The colonies to be screened were picked and patched onto the appropriate agar plates and grown overnight at 37°C. The colonies were lifted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose was exposed to chloroform vapor for 15 min in an airtight glass container. The colonies were lysed overnight at room temperature with gentle agitation in lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 μg/ml DNase I, 40 μg/ml lysozyme). The nitrocellulose membranes were then washed twice for 30 min each time in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (8 g/liter NaCl, 0.2 g/liter KCl, 1.15 g/liter Na2HPO4, 0.2 g/liter KH2PO4) and blocked with PBS-5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. The primary antibody was diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-1% skim milk and applied to the membranes for 2 to 4 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. The membranes were then washed three times in PBS for 10 min per wash, and the appropriate secondary antibody was diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-1% skim milk. The membrane was incubated with the secondary-antibody solution for 2 h at room temperature with gentle agitation, followed by three 10-min washes in PBS. The membrane was equilibrated in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) for 2 min and developed in diaminobenzidene developing solution (50 mg diaminobenzidine, 50 ml Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 30 μl H2O2) until sufficient color was obtained. The reaction was then stopped by immersing the membrane in distilled H2O.

Inverse PCR and Southern hybridization analyses.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes (Fermentas, Australia), followed by heat inactivation according to the manufacturer's instructions. Chromosomal DNA was then religated overnight in a final volume of 100 μl as described previously. Inverse PCR was then performed using the primer sequences 5′-TCAATTAGTTTATATAATAGATCC-3′ and 5′-TTAGTCAATTATCGGCTCG-3′, which were outward-facing sequences based on the adh and nrdF genes, respectively. The PCR products were DNA sequenced as previously described (37).

Southern transfer was performed as previously described (43). Dig-labeled nrdF PCR products were used as probes, and Southern hybridization analysis was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, Australia).

Induction of PBE strains and expression stability.

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium STM-1 strains harboring the pJLA507 series of constructs were grown in a 10-ml LB starter culture overnight at 37°C. The entire starter culture was used to inoculate a 50-ml LB culture, and the OD560 was adjusted to 0.4 with LB. The strains were grown for 1 h at 37°C. Induction was achieved by culturing the strains at 42°C. Growth curves in minimal medium supplemented with aromix were performed as previously described (33).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels were run as described by Sambrook et al. (43) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. For Western blot analysis, SDS-PAGE gels were electrophoresed but not stained. The samples were normalized by culture amount and visual analysis on Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE so that equivalent amounts were loaded in each lane. Western transfer and membrane blotting were performed as previously described (15). The membrane was then developed in diaminobenzidene developing solution (50 mg diaminobenzidine, 50 ml Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 30 μl H2O2) until sufficient color was obtained. The reaction was then stopped by immersing the membranes in distilled H2O. Alternatively, membranes were developed using a SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate kit (Pierce, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For pooled sera, the highest-responding mouse in each chromosomally based expression (CBE)-immunized group (as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] IgG response against Adh) was selected. Equal volumes of sera from these mice were then pooled, diluted 1:50, and used in Western blot analysis.

Animal immunization procedures.

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were caged separately according to treatment groups (10 mice per group). For live oral vaccinations, CBE cultures were grown to an OD560 of 1.0 and pelleted at 5,000 × g for 10 min. PBE cultures were induced at 42°C for 4 h and pelleted at 5,000 × g for 10 min. All oral vaccination strains were then resuspended in ice-cold PBS with 5% sucrose to an OD corresponding to 1 × 109 viable cells per 100 μl. The mice were deprived of drinking water for 3 h prior to oral immunization. After 3 h, the mice were orally immunized with a single 100-μl dose containing 1 × 109 viable cells delivered behind the incisors using a pipette tip. For intraperitoneal immunization, 50 μg of purified Adh or NrdF was diluted to a total volume of 50 μl in PBS and then mixed with an equal volume of Freund's incomplete adjuvant. The mice were then immunized with a 100-μl dose.

A total of three immunizations were performed for both the oral and intraperitoneal groups, each given 2 weeks apart. Two weeks after the final immunization, five mice in each group were euthanized with CO2 and exsanguinated by severing the brachial artery (day 42). Sera were collected and stored at −20°C. Lung wash samples were taken using 500 μl PBS containing 2 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and stored at −20°C. The remaining five mice in each group were given an intranasal antigen challenge 2 weeks later (day 56) consisting of 5 μg of Adh and 5 μg of NrdF in PBS (total volume, 10 μl). These mice were exsanguinated as described above 2 weeks after antigen challenge (day 70).

The generation of rabbit polyclonal NrdF and Adh antisera was performed as previously described (31).

To determine the in vivo stability of the STM-1 strains, five mice per group were orally inoculated with 1 × 109 CFU as described above. Ten days after inoculation, the mice were exsanguinated as described above and the spleens were removed. The spleens were homogenized in 5 ml ice-cold PBS and plated onto LB-rifampin (STM-sspA) or LB-streptomycin (all other strains). The total CFU were calculated, and 50 colonies (10 colonies per mouse) were randomly selected for further analysis. Southern blotting was performed as described above using a Dig-labeled nrdF probe to detect the presence of the operon. Western blotting was performed as described above with rabbit polyclonal Adh antisera.

ELISA protocols and statistical analysis.

ELISA was performed as previously described (16), and the results were analyzed using Softmax Pro 4.0 software (Molecular Devices, Australia). For whole-cell ELISA, STM-1 was streaked onto an agar plate and grown overnight at 37°C. A single colony was then used to inoculate 10 ml of LB and was grown in a 37°C shaking incubator until an OD600 of 1 was reached. The cells were pelleted at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was then resuspended in 10 ml of PBS-10% methanol. The cells were dispensed into 1-ml aliquots and stored at −20°C until they were required. The cells were thawed on ice, and 96-well ELISA plates (Interpath, Australia) were then coated with 50 μl of cells per well. The 96-well plates were centrifuged at 420 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The solution in the wells was removed, and the plates allowed to air dry. The plates were then blocked, incubated, and developed as described above.

Statistical significance was determined using a Student t test by comparison of each trial group to the PBS-negative control group. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Construction of PBE strains.

The goal of this study was to identify promoters useful for antigen expression in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. We devised a genetic screen using two M. hyopneumoniae antigens, Adh (F2P97) and NrdF. The adh gene encodes a domain containing both repeat regions of P97 (27). P97 is a proteolytically processed adhesin protein capable of binding swine cilia (11, 53). NrdF has been extensively studied as a putative vaccine candidate, and previous vaccination studies have demonstrated that NrdF can invoke Th1 and Th2 immune responses and improve the average daily weight gain of swine challenged with M. hyopneumoniae (7, 16, 17).

The cloning scheme of the PBE constructs is outlined in Fig. 1. NrdF and adh antigens were PCR amplified from M. hyopneumoniae chromosomal DNA and flanked with NdeI and SalI restriction sites, which facilitated cloning into pJLA507 to produce pJLA507-A (containing adh) and pJLA507-N (containing nrdF). The pJLA507-A vector was digested with XhoI/SalI, and adh was subcloned into the SalI site of pJLA507-N to produce pJLA507-AN. Plasmid pJLA507-AN is capable of expressing both antigens as individual proteins from the temperature-inducible PLPR promoter (45).

Construction of CBE strains.

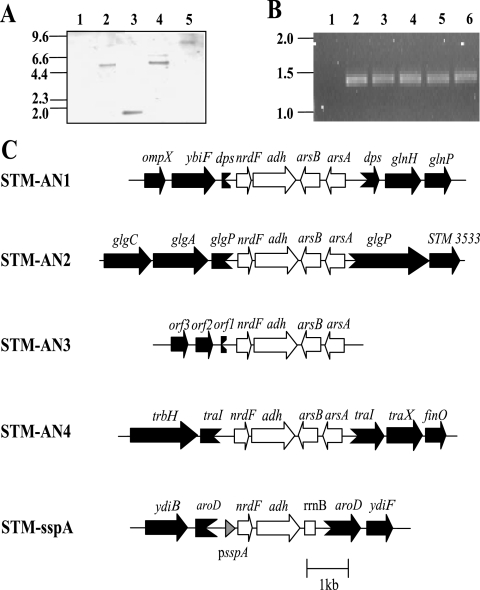

In order to attain antigen expression from single-copy non-antibiotic-resistant chromosomal constructs in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, CBE systems were engineered. Initially the promoterless nrdF-adh operon from pJLA507-AN was subcloned into pUC18Not, which flanked the nrdF-adh operon with NotI sites. Plasmid pUC18NotI-AN was digested with NotI, and the nrdF-adh operon was subcloned into pUT/Ars to produce pARS-AN (Fig. 1). Plasmid pARS-AN was then transformed into SM10 λpir, and a promoter-trapping experiment was performed whereby SM10 λpir(pARS-AN) was mated with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium STM-1. A total of 1,200 arsenite-resistant, ampicillin-sensitive STM-1 transconjugants were screened for the expression of Adh via colony immunoblotting (results not shown), and four highly expressing transconjugants were selected for further characterization. The presence of the nrdF-adh operon in the chromosomes of arsenite-resistant, Adh-expressing STM-1 colonies was confirmed using PCR and Southern hybridization analyses (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Chromosomal locations of antigen gene constructs. (A) Southern hybridization analysis of HindIII-digested chromosomal DNA from STM-1 vaccine strains using a Dig-labeled nrdF probe. Lanes: 1, STM-1; 2, STM-AN1; 3, STM-AN2; 4, STM-AN3; 5, STM-AN4. Molecular size markers in kb are indicated on the left. (B) PCR of the nrdF-adh operon from the chromosomes of STM-1 vaccine strains. Lanes: 1, STM-1; 2, STM-AN1; 3, STM-AN2; 4, STM-AN3; 5, STM-AN4; 6, STM-sspA. Molecular size markers in kb are indicated on the left. (C) Chromosomal locations of the nrdF-adh operon within STM-1 vaccine strains as determined using inverse PCR. Gene names are indicated. adh, M. hyopneumoniae F2P97; aroD, 3-dehydroquinase; arsA, arsenite-translocating ATPase; arsB, arsenite efflux membrane protein; dps, stress response DNA binding protein; finO, FinP binding protein; glgA, glycogen synthase; glgC, glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase; glgP, glycogen phosphorylase; glnH, high-affinity glutamine transport protein; glnP, glutamine transport permease protein; nrdF, M. hyopneumoniae ribonucleotide reductase; ompX, outer membrane protein X; orf, hypothetical open reading frame; psspA, promoter for stringent starvation protein A; rrnB, E. coli rRNA terminator; STM3533, putative transcriptional regulator; traI, OriT nickase/helicase; traX, pilin subunit acetylation; trbH, conjugative-transfer protein; ybiF, putative permease; ydiB, quinate/shikimate dehydrogenase; ydiF, putative acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA)/acetoacetyl-CoA transferase beta subunit. The scale in kb is indicated.

To construct the sspA chromosomal expression strain, pJLA507-AN was digested with NcoI and HindIII, and the promoterless nrdF-adh operon was subcloned into the NcoI and HindIII sites of pKKsspA to form pKKsspA-AN. The region from psspA to rrnBt, including the nrdF-adh operon, was PCR amplified and flanked with SphI and SacI sites. pCVDaroDins was digested with SphI and SacI, and the PCR product was cloned between these sites to form pCVD-AN (Fig. 1). pCVD-AN was transformed into E. coli S17.1 λpir and mated with STM-1 JA08. Double crossovers were selected using lacZ color screening, putative double crossovers were confirmed via PCR (Fig. 2), and a selected strain was designated STM-sspA.

Characterization of STM-1 expression strains.

Inverse PCR was performed to examine the insertion point of the nrdF-adh operon in the chromosome of STM-1 to determine which promoters were driving antigen expression. Once inverse-PCR products were generated, DNA sequence analysis was used to determine the point of insertion (Fig. 2). Briefly, expression of NrdF and Adh in STM-AN1 was under the control of the dps promoter. The dps gene encodes a DNA binding protein, which provides starvation-induced resistance to hydrogen peroxide (22). In STM-AN2, the nrdF-adh operon has been inserted into the glycogen metabolism operon, namely, the glycogen phosphorylase gene, glgP (2). In STM-AN4, the nrdF-adh operon has been inserted into a gene required for conjugal transfer, traI.

DNA sequence analysis of the inverse-PCR product obtained for STM-AN3 revealed that the construct had been inserted into a novel DNA sequence that showed no homology to any known Salmonella genome sequence. In order to confirm the existence of this novel sequence in STM-1, PCR primers were designed based on the sequence, and a PCR product was amplified from the genome of the original parental strain, STM-1 (data not shown). The PCR product was sequenced and was a 100% match to the original inverse-PCR product from STM-AN3 (data not shown). The sequence was assessed for putative open reading frames. A putative open reading frame (orf1) was found, and a Blastx search was performed. The sequence was 100% homologous to a hypothetical protein from Ralstonia solanacearum (accession number AL646052.1) (42). Analysis of other putative open reading frames (orf2 and orf3) revealed significant amino acid matches (99% and 100%, respectively) to other hypothetical Ralstonia pickettii proteins.

Expression profiles of PBE and CBE strains.

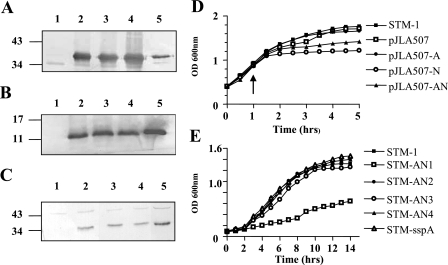

A comparison of the expression profiles of the recombinant constructs was performed. The expression of NrdF and Adh from STM-1(pJLA507-AN) is presented in Fig. 3. SDS-PAGE revealed a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 36 kDa evident 1 h postinduction (data not shown). Western blot analysis showed that the protein reacted with polyclonal Adh antiserum. Expression of the 11-kDa C terminus of NrdF was not apparent using SDS-PAGE (data not shown). However, Western blotting with polyclonal NrdF antiserum detected the expression of an 11-kDa band, confirming the expression of NrdF in STM-1(pJLA507-AN).

FIG. 3.

Growth curve and Western blot analyses of expression from STM-1(pJLA507-AN) and CBE strains. (A and B) Western blot of whole-cell lysates of STM-1(pJLA507-AN) using rabbit polyclonal Adh antisera (A) and rabbit polyclonal NrdF antisera (B). Lane 1, STM-1(pJLA507-AN) preinduction; lane 2, STM-1(pJLA507-AN) 1 h postinduction; lane 3, STM-1(pJLA507-AN) 2 h postinduction; lane 4, STM-1(pJLA507-AN) 4 h postinduction; lane 5, purified His-tagged Adh (200 ng) (A) or purified His-tagged NrdF (5 to 10 μg) (B). (C) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates of CBE strains using rabbit polyclonal Adh antisera. Lane 1, STM-1; lane 2, STM-AN1; lane 3, STM-AN2; lane 4, STM-AN3; lane 5, STM-AN4. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown on the left. (D) Growth curve analysis of PBE strains performed in LB. The strains were grown at 37°C for 1 h prior to induction at 42°C, indicated by the arrow. (E) Growth curves of CBE strains performed in minimal medium supplemented with aromix.

The expression profiles of the CBE strains are also displayed in Fig. 3. Neither Adh nor NrdF expression could be visualized using SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue (data not shown). Western blot analysis with polyclonal Adh antisera revealed the presence of a 36-kDa band corresponding to the correct mass of Adh in all CBE strains, with the exception of STM-sspA (data not shown). NrdF expression was faintly detected in the majority of the CBE strains, indicating that expression of NrdF was occurring but that the level of expression was at the very limit of detection (data not shown).

In vitro growth and stability of expression.

Growth curves of the CBE and PBE strains were performed to determine what effect the genetic manipulations had on the various strains' abilities to replicate in vitro (Fig. 3). The PBE strains were grown at mid-log phase for 1 h before induction at 42°C. Shortly after induction, two of the PBE strains, STM-1(pJLA507-N) and STM-1(pJLA507-AN), had static levels of growth. Both of the strains express NrdF, suggesting that the production of NrdF had a growth-inhibitory effect on STM-1. CFU counts were conducted, which confirmed that the overexpression of NrdF had a bacteriostatic effect on STM-1(pJLA507-N) and STM-1(pJLA507-AN) (data not shown).

Growth curves of the CBE strains were performed in minimal medium supplemented with aromix to ensure that the insertion of the nrdF-adh operon into the chromosome of STM-1 did not further attenuate the strains. Analysis of growth revealed that one strain, STM-AN1, replicated at a much lower rate than the other strains (Fig. 3). This indicated that the insertion of the nrdF-adh operon into the dps gene attenuated the growth of this strain in minimal medium, making it unsuitable for subsequent vaccination trial experiments.

The stability of antigen expression from the various PBE and CBE strains in vivo was examined. Mice were orally inoculated with 1 × 109 CFU, and the spleens were harvested 10 days postinoculation. Fifty colonies (10 per mouse) were randomly selected for each strain and analyzed by Southern blotting for the presence of the operon and by Western blotting for heterologous antigen expression (Table 2). Colonies were not detected in the spleens for any of the PBE strains or STM-AN2. The nrdF-adh operons in colonies that were detected for all other CBE strains showed 100% stability, and all colonies examined were capable of heterologous antigen expression.

TABLE 2.

Stability of the nrdF-adh operon and heterologous antigen expression in various S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA vaccine strains following 10 days of in vivo passage in mice

| Strain | Mouse no. | Total no. of CFU recovereda | Operon presence | Antigen expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STM-AN2 | 1 | 0 | NDb | ND |

| 2 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 3 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 4 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 5 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| STM-AN3 | 1 | 216 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| 2 | 102 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 3 | 36 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 4 | 421 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 5 | 712 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| STM-AN4 | 1 | 37 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| 2 | 65 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 3 | 65 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 4 | 167 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 5 | 16 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| STM-sspA | 1 | 25 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| 2 | 40 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 3 | 11 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 4 | 54 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| 5 | 15 | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| STM(pJLA507) | 1 | 0 | ND | ND |

| 2 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 3 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 4 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 5 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| STM(pJLA507-A) | 1 | 0 | ND | ND |

| 2 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 3 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 4 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 5 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| STM(pJLA507-AN) | 1 | 0 | ND | ND |

| 2 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 3 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 4 | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 5 | 0 | ND | ND |

In vivo stability determined by orally inoculating groups of five mice with 1 × 109 CFU of a single strain. Ten days after inoculation, the spleens were removed. S. enetrica serovar Typhimurium aroA was selected by plating homogenized spleens onto Rif LB agar (STM-sspA) or Sm LB agar (all other strains). Colonies were confirmed as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium by streaking them onto MacConkey agar. Ten colonies per mouse were randomly selected for further analysis.

ND, no data.

Immune responses of mice following oral vaccination.

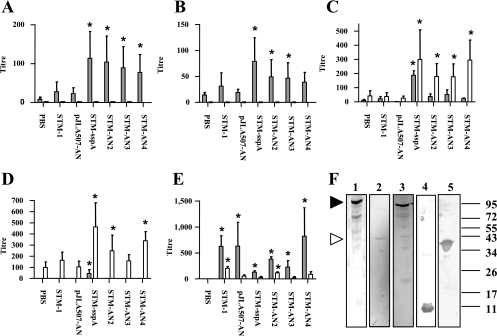

Mouse oral vaccination trials were conducted using the PBE and CBE strains. Mice were given either three oral immunizations with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains or three intraperitoneal vaccinations with purified Adh or NrdF. Fourteen days after the final vaccination, five mice in each group were sacrificed (day 42). As M. hyopneumoniae is not capable of infecting mice, immune recall was tested using purified recombinant antigens. Two weeks later, the remaining five mice were intranasally challenged with purified Adh and NrdF. Serum and lung wash responses were determined using ELISA (Fig. 4). Statistically significant (P < 0.05) serum IgM responses against Adh, NrdF, and STM-1 whole cells were detected for all CBE and purified intraperitoneal antigen mice at day 42, but not day 70. No IgM response against Adh or NrdF was detected among PBE mice, although there was an IgM STM-1 whole-cell response at day 42 (data not shown). Serum IgG responses against NrdF and Adh are shown in Fig. 4. At day 42, only the purified-intraperitoneal-antigen- and STM-sspA-vaccinated mice had significant IgG responses (P < 0.05) against Adh and NrdF. After intranasal challenge (day 70), all of the CBE and intraperitoneally vaccinated mice displayed significant serum IgG responses (P < 0.05) against both antigens, indicating that a systemic response had been induced. A serum IgG response against Adh or NrdF could not be detected at any time point for the PBE mice, although an IgG response against STM-1 whole cells was detected. The lung wash samples from the mice were analyzed for the presence of NrdF- and Adh-specific IgA and IgG; however, no significant response was detected at any time point (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Murine serum immunoglobulin responses against purified Adh, NrdF, and whole-cell STM-1 as determined by ELISA and Western blotting. Day 42 responses (shaded bars) and day 70 responses (white bars) are shown. The y axis represents reciprocal titer values. Standard errors are indicated. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) determined by comparison to the PBS group is indicated by asterisks. (A) Serum IgM responses against purified Adh. (B) Serum IgM responses against purified NrdF. (C) Serum IgG responses against purified Adh. (D) Serum IgG responses against purified NrdF. (E) Serum IgG responses against whole-cell STM-1. (F) Western blot analysis of pooled CBE orally immunized-mouse sera (day 42; diluted 1:50) and intraperitoneally immunized-mouse sera (day 42) against M. hyopneumoniae (strain J) whole-cell lysate and purified antigen. Lane 1, CBE orally immunized-mouse sera against M. hyopneumoniae whole-cell lysate; lane 2, NrdF intraperitoneally immunized-mouse sera against M. hyopneumoniae whole-cell lysate; lane 3, Adh intraperitoneally immunized-mouse sera against M. hyopneumoniae whole-cell lysate; lane 4, CBE orally immunized-mouse sera against purified NrdF; lane 5, CBE orally immunized-mouse sera against purified Adh. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown on the right. The filled arrowhead indicates the molecular mass of intact adhesin protein, and the unfilled arrowhead indicates the molecular mass of intact NrdF protein.

Pooled sera from orally immunized mice prior to intranasal challenge (day 42) were used in a Western blot against M. hyopneumoniae (strain J) whole-cell lysate, purified Adh, and purified NrdF (Fig. 4). The antiserum recognized a protein of approximately 95 kDa in the M. hyopneumoniae whole-cell lysate, which corresponds to the mature adhesin protein (27, 50). The antiserum also recognized the adhesin cleavage products, displaying the characteristic ladder pattern previously observed (28, 50, 53). This antiserum recognized a protein corresponding in mass to full-length NrdF (42 kDa) in the M. hyopneumoniae whole-cell lysates (15). The antiserum recognized both of the purified antigens, indicating that oral immunization of mice with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium is capable of eliciting specific serum IgG responses against both of the antigens.

DISCUSSION

Oral vaccination of recombinant, attenuated live bacterial expression systems is a promising method for heterologous antigen delivery. In this study, CBE of M. hyopneumoniae antigens in aroA-attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium elicited significant systemic immune responses. This approach to vaccine design has a number of advantages that allow it to be used for commercial applications. They include the use of non-antibiotic resistance markers, a stable expression system, low cost of production, and easy administration.

The PBE system used in this study failed to elicit any significant antigen-specific immune responses. Induction of expression in the PBE system was performed at 42°C so that the PBE strains would be loaded with overexpressed antigens upon administration. This is in contrast to the CBE strains, which expressed NrdF and Adh in vitro at much lower levels. Nonetheless, the CBE strains did elicit significant systemic (IgG and IgM) responses in vivo. Lowering the level of heterologous antigen expression may reduce the physiological stress on the host Salmonella strain, thus increasing the level of colonization and immune response (46). Colonies were not detected after 10 days of passage in vivo for any of the PBE strains examined. Expression of the antigens and the extra metabolic burden associated with maintaining the plasmid in vivo appear to have severely impacted the abilities of these strains to survive in the murine spleen, which also may have contributed to the lack of an antigen-specific immune response. Dunstan et al. (13) examined the abilities of aroA- and aroD-attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium harboring a range of tetanus toxin fragment C-expressing plasmids to survive in various murine organs after a single inoculation. The authors found colonies in the spleen up to 20 days postinoculation for all vectors examined, although they used an inoculum 10-fold greater than those examined here. This, along with the choice of plasmid vector, may have contributed to these contrasting results.

Overexpression of NrdF in the PBE strains had a bacteriostatic effect on S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, which most likely would have had a negative impact on its ability to invade and replicate in vivo. Such a bacteriostatic effect has been shown during the expression of a Mycoplasma arthritidis superantigen (10), which decreased the viability of the host E. coli cells. Therefore the results presented in this study suggest that the ability of live, aroA-attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium-based vaccines to replicate and express stably in vivo is more important than the level of antigen expression at immunization in generating systemic immune responses.

Characterization of STM-AN1 revealed the presence of the nrdF-adh operon within the dps gene. dps encodes a DNA binding protein that provides starvation-induced resistance to hydrogen peroxide, and expression is upregulated when Salmonella comes under oxidative stress during invasion of macrophages (22, 30). In E. coli, dps transcription is regulated in a sigma S- and IHF-dependent manner, and the IHF protein has been shown to bind upstream of the dps promoter (3). In this study, insertion of the nrdF-adh operon into dps further attenuated STM-AN1 in minimal medium supplemented with aromix. Given this result and the importance of dps during macrophage invasion, STM-AN1 was not used in the vaccine trial.

The nrdF-adh operon in STM-AN2 was inserted into glgP. This was the only CBE strain for which colonies could not be detected in the murine spleen 10 days after in vivo passage. Previous infection studies in chickens with a glycogen mutant S. enterica serovar Typhimurium had shown that glycogen metabolism has a minor role in colonization and pathogenesis but a more significant role in survival (36); this observation agrees with our findings. In this experiment, dual attenuation of aroA and glgP reduced the ability of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium to survive in vivo. Control of the glycogen metabolism pathway is thought to be allosterically regulated by ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (40). In E. coli, the binding of CsrA to glgCAP transcripts promotes glgCAP mRNA degradation, which inhibits glycogen metabolism (4). Transcriptional regulation of the operon in E. coli also appears to be controlled by RpoS (23). Recent microarray data suggest the glgP transcript was downregulated during Salmonella intracellular infection of murine macrophages, although it was below the significant threshold value (14). Despite this observation and the reduced ability of STM-AN2 to survive in the spleen, it was still able to elicit an antigen-specific IgG response.

The position of the nrdF-adh operon in STM-AN3 was able to be identified; however, the sequence did not match any known Salmonella sequence. The putative open reading frame (orf1) driving expression of the antigens had 100% amino acid homology to a hypothetical protein from the plant pathogen R. solanacearum (42) and a 99% match to a hypothetical protein from the human pathogen R. pickettii. Analysis of the translated sequence using the Pfam and Expasy databases revealed no matches with known proteins. As this sequence has not previously been reported in Salmonella, and given the strain's ability to survive in vivo, it is unlikely to be critical for pathogenesis.

STM-AN4, which contains the nrdF-adh operon inserted within the conjugal-transfer gene traI, displayed significant IgG titers after intranasal challenge. traI encodes OriT nickase/helicase (34) and catalyzes the unwinding of the DNA duplex while also acting as a sequence-specific DNA transesterase that provides the site/strand-specific nick required to initiate DNA transfer (32). Microarray analysis performed on the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium transcriptome during intracellular infection of murine macrophages did not examine traI transcript levels; however, the conjugal-transfer genes on either side (trbH and traX) both displayed significantly elevated transcript levels (14), suggesting that traI may also be upregulated during in vivo infection.

The importance of in vivo expression is further highlighted by the fact that STM1-sspA, which is upregulated in vivo (48), produced the only statistically significant CBE-generated response at day 42 against either Adh or NrdF. The expression of sspA in E. coli is induced during stationary phase while the bacterium is undergoing starvation for either carbon, amino acids, nitrogen, or phosphate (49). It has been previously demonstrated that S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA, expressing tetanus toxoid under the control of either single-copy (chromosomal) or multicopy (plasmid) sspAp, can generate significant immune responses in mice (48). The use of in vivo-inducible promoters for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium expression of heterologous antigens appears to be a promising approach, with the use of other promoters, such as ssaGp and pagCp, increasing the immunogenicity of heterologous antigens in murine models in comparison to native constitutive promoters (13, 35).

The strains capable of surviving for 10 days in vivo all displayed 100% stability of the nrdF-adh operon. Husseiny and Hensel (26) reported that integration of a heterologous antigen into purD of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium was stable after 9 days in vivo; however, they did not report whether the colonies were still capable of expression. All recovered colonies examined in this experiment were capable of heterologous antigen expression, demonstrating that the integrated operon was highly stable.

Previous studies were conducted using attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA to express single NrdF (7, 16, 17) or Adh (8) antigens. Fagan et al. (16) orally immunized mice with aroA-attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 expressing NrdF from pHSG398. This construct elicited NrdF-specific serum IgA and secretory IgA but failed to produce a significant serum IgG response. Chen et al. (7) expressed NrdF using plasmid-based prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression vectors in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA CS332, and they failed to elicit a humoral immune response in orally vaccinated mice. However, the splenocytes from the mice produced a significant level of IFN-γ when stimulated with NrdF, indicating the induction of a cell-mediated immune response (7). The varying results from this work and the previous trials indicate the importance of the choice of expression system and Salmonella strain for immunization purposes.

This study has demonstrated the ability of native Salmonella promoters to stably express heterologous, single-copy antigens from the chromosome and to generate systemic immune responses via the oral immunization route. The main advantages of this technique are that it can be used to generate immune responses against bacteriostatic antigens and can do so without the use of antibiotic resistance markers. The integration of the heterologous expression operon into the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium chromosome via a promoter-trapping technique allows many novel promoters and attenuation sites to be simultaneously assessed. This technique also allows the production of stable, cheap, easily administered vaccines that may be used in a commercial setting.

Acknowledgments

The work presented here was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award (Industry) to Jake Matic, an Australian Research Council Linkage grant, and Bioproperties, Melbourne, Australia.

Editor: F. C. Fang

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderton, M. R., K. J. Fahey, and P. J. Coloe. 1991. Humoral responses and salmonellosis protection in chickens given a vitamin-dependent Salmonella typhimurium mutant. Avian Dis. 35435-442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso-Casajus, N., D. Dauvillee, A. M. Viale, F. J. Munoz, E. Baroja-Fernandez, M. T. Moran-Zorzano, G. Eydallin, S. Ball, and J. Pozueta-Romero. 2006. Glycogen phosphorylase, the product of the glgP gene, catalyzes glycogen breakdown by removing glucose units from the nonreducing ends in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1885266-5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altuvia, S., M. Almirón, G. Huisman, R. Kolter, and G. Storz. 1994. The dps promoter is activated by OxyR during growth and by IHF and sigma S in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 13265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker, C. S., I. Morozov, K. Suzuki, T. Romeo, and P. Babitzke. 2002. CsrA regulates glycogen biosynthesis by preventing translation of glgC in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 441599-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brayden, D. J., M. A. Jepson, and A. W. Baird. 2005. Keynote review: intestinal Peyer's patch M cells and oral vaccine targeting. Drug Discov. Today 101145-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatfield, S. N., I. G. Charles, A. J. Makoff, M. D. Oxer, G. Dougan, D. Pickard, D. Slater, and N. F. Fairweather. 1992. Use of the nirB promoter to direct the stable expression of heterologous antigens in Salmonella oral vaccine strains: development of a single-dose oral tetanus vaccine. Biotechnology 10888-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, A. Y., S. R. Fry, J. Forbes-Faulkner, G. E. Daggard, and T. K. Mukkur. 2006. Comparative immunogenicity of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae NrdF encoded in different expression systems delivered orally via attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA in mice. Vet. Microbiol. 114252-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, A. Y., S. R. Fry, J. Forbes-Faulkner, G. Daggard, and T. K. Mukkur. 2006. Evaluation of the immunogenicity of the P97R1 adhesin of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae as a mucosal vaccine in mice. J. Med. Microbiol. 55923-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, C. M., H. L. Mobley, and B. P. Rosen. 1985. Separate resistances to arsenate and arsenite (antimonate) encoded by the arsenical resistance operon of R factor R773. J. Bacteriol. 161758-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diedershagen, M., S. Overbeck, S. Arlt, B. Plümäkers, M. Lintges, and L. Rink. 2007. Mycoplasma arthritidis-derived superantigen (MAM) displays DNase activity. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 49266-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djordjevic, S. P., S. J. Cordwell, M. A. Djordjevic, J. Wilton, and F. C. Minion. 2004. Proteolytic processing of the Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae cilium adhesin. Infect. Immun. 722791-2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunstan, S. J., C. P. Simmons, and R. A. Strugnell. 1999. Use of in vivo-regulated promoters to deliver antigens from attenuated Salmonella enterica var. Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 675133-5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunstan, S. J., C. P. Simmons, and R. A. Strugnell. 2003. In vitro and in vivo stability of recombinant plasmids in a vaccine strain of Salmonella enterica var. Typhimurium. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 37111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson, S., S. Lucchini, A. Thompson, M. Rhen, and J. C. Hinton. 2003. Unravelling the biology of macrophage infection by gene expression profiling of intracellular Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 47103-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagan, P. K., S. P. Djordjevic, G. J. Eamens, J. Chin, and M. J. Walker. 1996. Molecular characterization of a ribonucleotide reductase (nrdF) gene fragment of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and assessment of the recombinant product as an experimental vaccine for enzootic pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 641060-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagan, P. K., S. P. Djordjevic, J. Chin, G. J. Eamens, and M. J. Walker. 1997. Oral immunization of mice with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium aroA expressing a recombinant Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae antigen (NrdF). Infect. Immun. 652502-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagan, P. K., M. J. Walker, J. Chin, G. J. Eamens, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2001. Oral immunization of swine with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium aroA SL3261 expressing a recombinant antigen of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (NrdF) primes the immune system for a NrdF specific secretory IgA response in the lungs. Microb. Pathog. 30101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friis, N. F. 1975. Mycoplasms of the swine—a review. Nord. Vet. Med. 27329-336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gahan, M. E., D. E. Webster, S. L. Wesselingh, and R. A. Strugnell. 2007. Impact of plasmid stability on oral DNA delivery by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Vaccine 251476-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garmory, H. S., S. E. Leary, K. F. Griffin, E. D. Williamson, K. A. Brown, and R. W. Titball. 2003. The use of live attenuated bacteria as a delivery system for heterologous antigens. J. Drug Target. 11471-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin, H. G., T. J. Foster, S. Silver, and T. K. Misra. 1987. Cloning and DNA sequence of the mercuric- and organomercurial-resistance determinants of plasmid pDU1358. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 843112-3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halsey, T. A., A. Vazquez-Torres, D. J. Gravdahl, F. C. Fang, and S. J. Libby. 2004. The ferritin-like Dps protein is required for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium oxidative stress resistance and virulence. Infect. Immun. 721155-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hengge-Aronis, R., and D. Fischer. 1992. Identification and molecular analysis of glgS, a novel growth-phase-regulated and rpoS-dependent gene involved in glycogen synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 61877-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1726557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hone, D., S. Attridge, L. van den Bosch, and J. Hackett. 1988. A chromosomal integration system for stabilization of heterologous genes in Salmonella based vaccine strains. Microb. Pathog. 5407-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husseiny, M. I., and M. Hensel. 2005. Rapid method for the construction of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine carrier strains. Infect. Immun. 731598-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins, C., J. L. Wilton, F. C. Minion, L. Falconer, M. J. Walker, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2006. Two domains within the Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae cilium adhesin bind heparin. Infect. Immun. 74481-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King, K. W., D. H. Faulds, E. L. Rosey, and R. J. Yancey, Jr. 1997. Characterization of the gene encoding Mhp1 from Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and examination of Mhp1's vaccine potential. Vaccine 1525-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon, Y. M., M. M. Cox, and L. N. Calhoun. 2007. Salmonella-based vaccines for infectious diseases. Exp. Rev. Vaccines 6147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall, D. G., A. Haque, R. Fowler, G. Del Guidice, C. J. Dorman, G. Dougan, and F. Bowe. 2000. Use of the stationary phase inducible promoters, spv and dps, to drive heterologous antigen expression in Salmonella vaccine strains. Vaccine 181298-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matic, J. N., J. L. Wilton, R. J. Towers, A. L. Scarman, F. C. Minion, M. J. Walker, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2003. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae contains a novel lipoyl domain arrangement. Gene 31999-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matson, S. W., J. K. Sampson, and D. R. Byrd. 2001. F plasmid conjugative DNA transfer: the TraI helicase activity is essential for DNA strand transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2762372-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McArthur, J. D., N. P. West, J. N. Cole, H. Jungnitz, C. A. Guzmán, J. Chin, P. R. Lehrbach, S. P. Djordjevic, and M. J. Walker. 2003. An aromatic amino acid auxotrophic mutant of Bordetella bronchiseptica is attenuated and immunogenic in a mouse model of infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2217-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClelland, M., K. E. Sanderson, J. Spieth, S. W. Clifton, P. Latreille, L. Courtney, S. Porwollik, J. Ali, M. Dante, F. Du, S. Hou, D. Layman, S. Leonard, C. Nguyen, K. Scott, A. Holmes, N. Grewal, E. Mulvaney, E. Ryan, H. Sun, L. Florea, W. Miller, T. Stoneking, M. Nhan, R. Waterston, and R. K. Wilson. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKelvie, N. D., R. Stratford, T. Wu, T. Bellaby, E. Aldred, N. J. Hughes, S. N. Chatfield, D. Pickard, C. Hale, G. Dougan, and S. A. Khan. 2004. Expression of heterologous antigens in Salmonella typhimurium vaccine vectors using the in vivo-inducible, SPI-2 promoter, ssaG. Vaccine 223243-3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMeechan, A., M. A. Lovell, T. A. Cogan, K. L. Marston, T. J. Humphrey, and P. A. Barrow. 2005. Glycogen production by different Salmonella enterica serotypes: contribution of functional glgC to virulence, intestinal colonization and environmental survival. Microbiology 1513969-3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMillan, D. J., M. Mau, and M. J. Walker. 1998. Characterisation of the urease gene cluster in Bordetella bronchiseptica. Gene 208243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNeill, H. V., K. A. Sinha, C. E. Hormaeche, J. J. Lee, and C. M. Khan. 2000. Development of a nonantibiotic dominant marker for positively selecting expression plasmids in multivalent Salmonella vaccines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 661216-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakayama, K., S. M. Kelly, and R. Curtiss III. 1988. Construction of an Asd+ expression cloning vector: stable maintenance and high level expression of cloned genes in a Salmonella vaccine strain. BioTechnology 6693-697. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preiss, J. 1984. Bacterial glycogen synthesis and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 38419-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roland, K. L., S. A. Tinge, K. P. Killeen, and S. K. Kochi. 2005. Recent advances in the development of live, attenuated bacterial vectors. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 762-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salanoubat, M., S. Genin, F. Artiguenave, J. Gouzy, S. Mangenot, M. Arlat, A. Billault, P. Brottier, J. C. Camus, L. Cattolico, M. Chandler, N. Choisne, C. Claudel-Renard, S. Cunnac, N. Demange, C. Gaspin, M. Lavie, A. Moisan, C. Robert, W. Saurin, T. Schiex, P. Siguier, P. Thébault, M. Whalen, P. Wincker, M. Levy, J. Weissenbach, and C. A. Boucher. 2002. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Nature 415497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 44.Scarman, A. L., J. C. Chin, G. J. Eamens, S. F. Delaney, and S. P. Djordjevic. 1997. Identification of novel species-specific antigens of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae by preparative SDS-PAGE ELISA profiling. Microbiology 143663-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schauder, B., H. Blocker, R. Frank, and J. E. McCarthy. 1987. Inducible expression vectors incorporating the Escherichia coli atpE translational initiation region. Gene 52279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spreng, S., G. Dietrich, and G. Weidinger. 2006. Rational design of Salmonella-based vaccination strategies. Methods 38133-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strugnell, R. A., D. Maskell, N. Fairweather, D. Pickard, A. Cockayne, C. Penn, and G. Dougan. 1990. Stable expression of foreign antigens from the chromosome of Salmonella typhimurium vaccine strains. Gene 8857-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terry, T. D., J. E. Downes, S. J. Dowideit, A. N. Mabbett, and M. P. Jennings. 2005. Investigation of ansB and sspA derived promoters for multi- and single-copy antigen expression in attenuated Salmonella enterica var. Typhimurium. Vaccine 234521-4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams, M. D., T. X. Ouyang, and M. C. Flickinger. 1994. Starvation-induced expression of SspA and SspB: the effects of a null mutation in sspA on Escherichia coli protein synthesis and survival during growth and prolonged starvation. Mol. Microbiol. 111029-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilton, J. L., A. L. Scarman, M. J. Walker, and S. P. Djordjevic. 1998. Reiterated repeat region variability in the ciliary adhesin gene of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Microbiology 1441931-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu, F., and J. B. Ulmer. 2003. Attenuated Salmonella and Shigella as carriers for DNA vaccines. J. Drug Target. 11481-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang, Q., T. F. Young, and R. F. Ross. 1995. Identification and characterization of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae adhesin. Infect. Immun. 631013-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]