Abstract

Pur-alpha is a ubiquitous multifunctional protein that is strongly conserved throughout evolution, binds to both DNA and RNA and functions in the initiation of DNA replication, control of transcription and mRNA translation. In addition, it binds to several cellular regulatory proteins including the retinoblastoma protein, E2F-1, Sp1, YB-1, cyclin T1/Cdk9 and cyclin A/Cdk2. These observations and functional studies provide evidence that Purα is a major player in the regulation of the cell cycle and oncogenic transformation. Purα also binds to viral proteins such as the large T-antigen of JC virus (JCV) and the Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and plays a role in the cross-communication of these viruses in the opportunistic polyomavirus JC (JCV) brain infection, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). The creation of transgenic mice with inactivation of the PURA gene that encodes Purα has revealed that Purα is critical for postnatal brain development and has unraveled an essential role of Purα in the transport of specific mRNAs to the dendrites and the establishment of the postsynaptic compartment in the developing neurons. Finally, the availability of cell cultures from the PURA knockout mice has allowed studies that have unraveled a role for Purα in DNA repair.

Keywords: Purα, cell cycle, DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, JC virus, mRNA transport

Introduction

In this review, we will consider four important aspects of the protein, Purα. Firstly, we will consider its role in the regulation of transcription, the cell cycle and in oncogenic transformation. Secondly, we will describe how Purα is involved in the interplay between the viruses HIV-1 and JCV, and hence in the pathogenesis of AIDS-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Thirdly, we will examine what has been learned about the importance of Purα in brain development through the use of transgenic mice where the gene encoding Purα has been deleted. This has revealed a critical role for Purα in transporting specific mRNAs to the postsynaptic dendritic compartment of neurons, which is discussed in the fourth section. Finally, a function for Purα in DNA repair is discussed, which has been revealed using fibroblast cultures derived from the PURA knockout mice.

Purα: A Key Cellular Protein that Functions to Regulate Transcription and the Cell Cycle and is Involved in Oncogenic Transformation

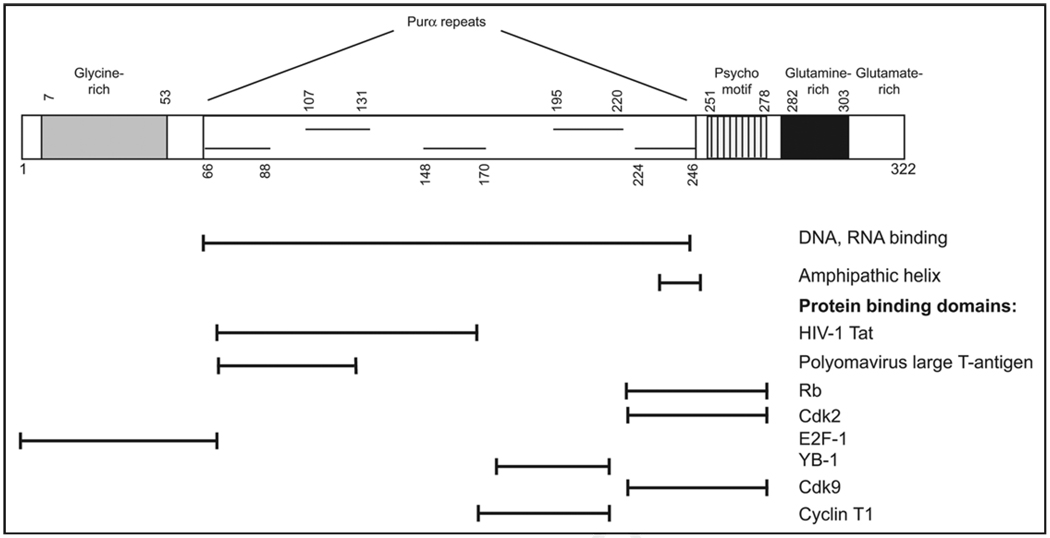

Purα is a ubiquitous nucleic acid-binding protein that was originally purified from mouse brain based on its ability to bind to a DNA sequence derived from the promoter of the mouse myelin basic protein gene.1,2 Human Purα was characterized by its ability to bind to a DNA sequence present upstream of the human c-Myc gene, its cDNA was cloned from HeLa cells and sequenced.3,4 The sequence of mouse Purα5 is almost identical to human Purα4 with only 2 out of 322 amino acid residues differing. Purα has a modular structure with a central DNA-binding domain containing 3 class I repeats and 2 class II repeats (Fig. 1). Other notable structural features include an N-terminal glycine-rich domain, a “psycho” domain,5 and C-terminal glutamine-rich and glutamate-rich domains. The DNA-binding domain of Purα is strongly conserved throughout evolution.

Figure 1.

Structure of Purα. A schematic representation of the structure of the Purα protein showing its modular structure is shown. The N-terminus contains a glycine-rich domain that contains a stretch of 18 glycine residues interrupted only by a single serine. The central DNA-binding domain containing 3 class I repeats and 2 class II repeats. The “psycho” domain has homology to polyomavirus large-T antigen from SV40, JCV or BKV and other proteins.5 Also shown are the C-terminal glutamine-rich and glutamate-rich domains. The regions of Purα that are involved in interacting with other proteins have been experimentally determined in a number of cases: HIV-1 Tat,12 T-antigen,45 pRb,38 Cdk2,6 E2F-1,40 YB-1,42 Cdk9,14 and Cyclin T1.14

Purα is a member of the Pur family of proteins along with Purβ4 and Purγ for which there exist two isoforms that arise from the usage of alternative polyadenylation sites,6 and it is expressed in virtually every metazoan tissue.7 Purα is a multifunctional protein that can bind to both DNA and RNA and functions in the initiation of DNA replication, control of transcription and mRNA translation.7,8 Purα associates with DNA sequences that are close to viral and cellular origins of replication. Since initiation of transcription and replication requires unwinding of duplex DNA, this is consistent with Purα being a single-stranded nucleic acid-binding protein that possesses DNA helix-destabilizing activity.9 In vitro studies of the unwinding ability of Purα have shown that it can bind to both linearized or supercoiled plasmid DNAs, which gives rise to a series of regularly spaced bands observed by agarose gel electrophoresis. These bands are likely due to Purα-mediated step-wise unwinding of DNA since Purα increases the sensitivity of the DNA to potassium permanganate which is specific for unwound regions and also creates binding sites for the phage T4 ss-DNA binding protein, gp32.10

A role in transcriptional activation for Purα is supported by reports that it can function as a transcriptional activator for several genes including the early and late promoters of polyomavirus, JC,11,12 the HIV-1 LTR,13 and the promoters of the cellular genes encoding TNFα,14 myelin basic protein,1,2,15,16 β2-integrin,17 placental lactogen,18 CD11c beta-2 integrin,19 TGFβ-1,20 the neuron-specific FE65 protein21 and PDGF-A.22 A recent proteomic analysis showed that Purα binds to an intronic enhancer in the myelin proteolipid Plp1 protein gene, which is responsible for a surge of Plp1 production during the active myelination period of CNS development.23

Conversely, it has also been reported that in the case of various other genes, Purα has a negative effect on transcription, i.e., that it acts as a repressor of gene expression. Interestingly, Purα negatively regulates transcription of the promoter of its own gene, i.e., auto-regulation. 24 Purα also negatively regulates the expression of other cellular genes including α-actin,25–28 amyloid-β protein precursor,29 CD43,30,31 α-myosin,32 fas,33 gata2,34 and somatostatin.35

Purα binds to both single-stranded and double-stranded DNA and its preferred recognition sequence is composed of repeats of (GGN). Interaction of Purα with its recognition sequence results in the formation of multimeric complexes and is modulated by the binding and interaction of other transcription factors.7,8,36 For example, Purα association with the YB1 transcription factor and histone H1.2 at the promoter for the p53 target gene Bax is required for repression of p53-induced transcription.36 Purα is also able to collaborate with the transcription factors Purβ and Sp3 to negatively regulate β-myosin heavy chain gene expression in skeletal muscle.37

Several lines of evidence suggest that Purα is a major player in the regulation of the cell cycle and oncogenic transformation. Purα binds to several cellular regulatory proteins including the retinoblastoma protein,38 E2F-1,39–41 Sp1,15 YB-1,42 cyclin T1/Cdk9,14 and cyclin A/Cdk2.43,44 Purα also binds to the large T-antigen of JCV45 and to the Tat protein of HIV-1.12 The intracellular level of Purα varies during the cell cycle, declining at the onset of S-phase and peaking during mitosis.43 This cyclical variation of cellular Purα levels may be regulated by an element within the Purα promoter, which is involved in mediating antagonistic effects of Purα and E2F-1 on Purα gene expression.41 When microinjected into NIH-3T3 cells, Purα causes cell cycle arrest at either the G1/S or G2/M check-points46 and when expressed in Ras-transformed NIH-3T3 cells, Purα inhibits their ability to grow in soft agar.47 Ectopic overexpression of Purα suppresses the growth of several transformed and tumor cells including glioblastomas.48 The growth-inhibitory effects of Purα are consistent with gene expression profiling in chronic myeloid leukemia patients where downregulation of Purα expression was observed.49 Furthermore, deletions of Purα have been reported in myelodysplastic syndrome, a condition that can progress to acute myelogenous leukemia consistent with a role for Purα as a tumor suppressor.50 In the case of prostate cancer, Purα loss may also be associated with cancer progression.51 It has been reported that Purα is a repressor of the promoter for the androgen receptor and its loss is a determinant of androgen receptor overexpression and hence androgen-independent progression of prostate cancer.52

Thus Purα is an important transcription factor and regulator of the cell cycle that interacts with key cellular control proteins and exerts a critical role in the regulation of cell proliferation.

Role of Tat and Purα in JCV Transactivation: Importance in the Pathogenesis of PML in HIV/AIDS

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS) caused by the human polyomavirus JC (JCV). PML is characterized by multiple regions of demyelination, which are developed upon lytic infection of oligodendrocytes, the myelin-producing cells of the CNS, by JCV. Destruction of oligodendrocytes leads to brain lesions and death.53–55 JCV is ubiquitous among the general population with greater than 80% of adults exhibiting JCV-specific antibodies. Infection is thought to take place during early childhood and is usually subclinical. However, only individuals with severely impaired immunity, mainly AIDS patients, develop PML.

AIDS has been estimated to be the underlying cause of immunosuppression in from 55% to more than 85% of cases of PML.56,57 Indeed, PML is considered as an AIDS-defining illness.58 The occurrence of PML was very rare until the advent of the AIDS pandemic but now it is much more prevalent and affects ~5% of HIV-infected persons.59 JCV is one of the few opportunistic infections that continue to occur with some frequency in patients with AIDS despite the widespread use of HAART.59,60 The incidence of PML complicating HIV/AIDS is higher than that of any other immunosuppressive disorder relative to their frequencies. There are a number of reasons why this may be the case. Firstly, the degree and duration of cellular immunosuppression in HIV/AIDS may be greater in AIDS compared to other immunosuppressive disorders.56,59 JCV-specific CD4 T-cell responses are impaired in HIV-infected patients with active PML compared to PML survivors on effective and prolonged antiretroviral therapy.61 Secondly, HIV/AIDS may erode the blood brain barrier62 and facilitate the entry of B-lymphocytes infected with JCV into the brain.63 Indeed, very recent findings suggest a role for B-lymphocytes in rearrangement of the JCV genome that may be involved in PML pathogenesis.64,65 Finally there exists a specific molecular mechanism whereby HIV-1 promotes JCV gene expression and participates in the pathogenesis of PML. This is the cross-communication between HIV-1 and JCV through the HIV-1 encoded regulatory protein Tat and the mechanism whereby this occurs involves Purα.

Tat has the ability to bind to and enhance the transcription of the JCV promoter in glial cells through a strong stimulation of the basal activity of the JCV late promoter.66 This stimulation by Tat was synergistic with the stimulation caused by JCV T-antigen.67 Activation of the JCV late transcription was found to occur through a Tat-responsive transcriptional control element and to be mediated by association of Tat with Purα.12,68 As well as transactivating JCV transcription, Tat also stimulates viral DNA replication.69 It is established that Tat can be released from HIV-1-infected cells and taken up again by neighboring cells.70,71 Thus the reactivation of JCV by HIV-1 need not require the coinfection of glial cells with both viruses. Indeed it has been shown that internalization of exogenous Tat by oligodendroglioma cells is followed by colocalization with endogenous Purα and stimulation of DNA replication initiated at the JC virus origin.72

Studies of the mechanism of Tat action on the JCV late promoter demonstrated that Tat protein mediates activation of a Tat-responsive transcriptional control element by associating with Purα.12 The high affinity Tat/Purα complex binds to a Tat-responsive JCV element, upTAR, which consists of the canonical PURα binding element GGAGGCGGAGGC. Tat and Purα act synergistically to activate JCV late gene expression by a factor of more than 100-fold.12 In addition, it has demonstrated that HIV-1 Tat stimulates transcription of the transforming growth factor, TGFβ-1, gene in glial cells and that this also involves the action of Purα on the TGFβ-1 promoter.20

Purα also binds the HIV-1 TAR RNA element and activates HIV-1 transcription, suggesting a role for RNA binding in the action of this protein.13 The interaction between Tat and Purα is mediated by RNA and involves specific regions of both the Tat and Purα proteins.73,74 Activation of the HIV-1 LTR by Tat requires several cellular proteins including cyclin T1 and its partner, cdk9, which associate with the TAR sequence within the LTR, forming a complex that enhances the activity of RNA polymerase II. However, Tat also causes the transcriptional activation of the TNFα promoter which has no TAR sequence and this also shows cooperativity of Purα with cyclin T1 and cdk9 suggesting that Purα has a role in assembling Tat, cyclin T1, and cdk9 around the promoter region of TAR-negative genes such as TNFα.14

In addition to HIV-1 Tat, it was recently found that Purα interacts with another HIV-1 accessory protein, Rev.75 Rev-mediated RNA transport is a mechanism that allows the export from the nucleus of unspliced HIV-1 genomic RNA and requires the Rev-responsive element (RRE) that lies within the viral Env gene. Purα was found to interact with Rev to enhance the cytoplasmic delivery of unspliced viral RNA. When Purα protein was depleted using an RNA interference approach, the level of Rev-dependent viral RNA expression was reduced. This effect was mediated through Purα interaction with Rev protein and binding of Purα with the RRE itself.75 In addition to HIV-1 viral RNA, Purα has been found to be involved in the transport of cellular RNAs and this is discussed below.

Function of Purα in Postnatal Brain Development: Lessons from the PURA−/− Transgenic Mouse

The generation of transgenic mice with inactivation of the PURA gene that encodes Purα has revealed that Purα has an essential role in postnatal brain development.55 Mice with targeted disruption of the PURA gene in both alleles (PURA−/−) appear normal at birth, but at two weeks of age, they develop neurological problems and they die by four weeks. There are much fewer cells in the brain cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum of PURA−/− mice than in PURA+/+ controls and immunohistochemical analysis of the MCM7 marker for DNA replication revealed a lack of proliferation of the precursor cells that are found in this region. This implicates Purα in the regulation of developmentally timed DNA replication in specific cell types in the brain. Moreover, the brains of the PURA−/− mice also exhibited pathological development of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, which exhibited reduced immunolabeling for the cell type-specific markers glial fibrillary acidic protein and myelin respectively. Interestingly at postnatal day 5 in PURA+/+ mice, which is a critical time for cerebellar development, Purα and Cdk5 were present at high levels n the cell bodies and the dendrites of Purkinje cells, while both were absent in the dendrites of PURA−/− mice. There was also a pronounced reduction in synapse formation in the hippocampus and the levels of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated neurofilaments in the dendrites of the Purkinje cell layer were also reduced.55 Further studies indicated that the PURA−/− mice showed changes in Purkinje cell dendritic localization of two proteins, Staufen and Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP), which are thought to function in the transport of specific mRNAs to the dendrites.76 A role for Purα in the transport of specific mRNAs is discussed in the next section. Finally, the availability of primary cultures of mouse embryo fibroblasts from the PURA−/− mice provide a cell system in which to analyze the role of Purα in many basic cellular processes as described below.

Function of Purα in the Regulation of mRNA Transport and Translation

As described above, Purα is an RNA-binding protein. For example, association of Purα with 7SL RNA is involved in the developmental stage regulation of the myelin basic protein gene promoter in mouse brain.77 The phenotype of the PURA−/− described in the previous section involves defective brain development and this is likely due, at least in part, to Purα having an essential role in the transport of specific mRNAs to the dendrites in the developing brain. In the neurons of the brain, a specialized protein synthetic apparatus is thought to function in the local compartments of dendrites, especially near synaptic junctions and that this allows rapid adjustments of the postsynaptic protein repertoire. Thus, selected mRNAs have been identified in these compartments. A specific RNA polymerase III-directed transcript has also been identified in dendrites known as BC1 RNA, which is a noncoding, 152-nucleotide-long, single-gene transcript, expressed almost exclusively in the nervous system and functions as part of a high molecular weight ribonucleoprotein in specific direction of mRNAs to the postsynaptic compartments of neurons.78 Neural BC1 RNA is distributed in neuronal dendrites as RNA:protein complexes (BC1 RNPs) containing the proteins, Purα and its isoform Purβ, which link BC1 RNA to microtubules.79 The binding site is located within the 5' proximal region of BC1 RNA, which contains the putative dendrite-targeting RNA motifs rich in G/U residues, suggesting that Purα and Purβ are involved in the BC1 RNA transport along dendritic microtubules. Also found in the dendritic polyribosomal particles are the proteins, Staufen, FMRP, myosin Va, and other proteins of unknown function.80 Coimmunoprecipitation of these proteins by antibody to Purα is abolished by RNase treatment indicating hat mRNP assembly occurs in an RNA-dependent manner. Furthermore, these mRNPs appear to be equipped with a kinesin motor and may form the molecular machinery mediating transport of polyribosomes along microtubules and actin filaments, as well as localized translation within the dendritic compartment.80 Consistent with a role for Purα in this process, PURA−/− mice exhibit disruption of Purkinje cell dendritic localization of Staufen and FMRP in the developing mouse cerebellum.76 Furthermore, immunohistochemistry of PURA−/− mouse brain sections of both the cerebellum and the hippocampus with antibody against microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), which is considered a dendritic marker, revealed very little labeling for MAP2 indicating the importance of Purα in the development of dendrites. Similarly, in primary cultures of rat hippocampal neurons, Purα colocalizes with MAP2 but not Ankyrin G, an axonal marker.76 The simultaneous presence of different proteins on a single RNA species can be investigated using the technique of double RNA immunoprecipitation, which has been used to demonstrate that Purα and Staufen and FMRP are present at the same time on mouse brain BC1 RNA, MAP2 mRNA and MAP1B mRNAs but not on Ankyrin G mRNA.76

In addition to Staufen and FMRP, other proteins are likely important for Purα function in the regulation of mRNA transport and translation. Zeng et al.81 reported the characterization of novel Purα-binding proteins in mouse brain. Using an overlay assay with GST-Purα as a ligand, three Purα-binding proteins of 35, 38 and 40 kDa were detected that could be competed with ssDNA containing a Purα binding motif and were as abundantly expressed in the brain as Puralpha. Further studies identified an additional two novel Purα-binding proteins (30 and 32 kDa), which showed spatiotemporal translocation with Purα from nuclei to cytoplasm during neuronal development.82 Using fusion protein of GST and the C-terminus of the conventional kinesin KIF5 (kinesin binds to cargo via its tail domain) to create affinity columns, Kanai et al.83 isolated a large (~1000S) RNase-sensitive granule from mouse brain as a binding partner of KIF5. This granule contained many proteins including hnRNP-U, Purα, Purβ, PSF, DDX1, DDX3, SYNCRIP, TLS, NonO, HSPC117, ALY, CGI-99, Staufen, three FMRPs and EF-1α. Co-immunoprecipitation in the presence of RNase demonstrated that Purα, and Purβ, PSF and NonO, and DDX1 and CGI-99 showed strong interactions with each other. Immunofluorescence studies revealed that eight of these proteins (Purβ, DDX3, SYNCRIP, Staufen, FMRPs and EF-1α) showed somatodendritic patterns colocalizing to the Purα-containing granules in the dendrites, while hnRNP-U, PSF, TLS, NonO and ALY were observed only in the nucleus. RNA interference studies demonstrated an essential role for Purα, hnRNP-U, PSF and Staufen in granule transport.83 Another novel protein component of Purα-containing mRNA-protein particles was recently identified, designated C9orf10 protein and characterized.84 Also recently described is the interaction of the retinoic acid receptor-α (RARα) with Purα and other RNA-binding proteins by tandem affinity purification. Confocal microscopy confirmed localization of neuronal RARα in dendritic RNA granules with Purα alpha and FMRP. This suggests a mechanism for rapid stimulation of dendritic growth and translation by retinoic acid.85

What is the known of the mechanism whereby Purα binds to its RNA targets? Sequence similarities exist between RNA species known to be functional targets that bind Purα. Purα binds to the rat brain BC1 RNA,86 mouse brain 7SL RNA77 and the HIV-1 RNA TAR element.13 These non-coding RNAs each possess a conserved, potential stem-and-loop structure. Evidence from electrophoretic mobility shift assays suggests that this region is the binding site for Purα.76

Role of Purα in DNA Repair

The generation of transgenic mice in which the PURA gene has been activated has allowed the culture of Purα knockout mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) to be cultured and to be used to analyze the functions of Purα. We have used such cells to analyze the role of Purα in the cellular response to replication-associated DNA repair of double-strand breaks (DSBs). Purα-negative MEFs are hypersensitive to the DNA replication inhibitor, hydroxyurea, which induces excessive DSBs and causes a delay in the resumption of cell cycle progression after hydroxyurea treatment.87 The effect of Purα on cell cycle progression after DNA damage was confirmed in human HeLa cells using RNA interference with a Purα siRNA.87 This hypersensitivity to hydroxyurea treatment suggests that Purα may act as a caretaker protein that is involved in the repair of DSBs induced by stalled replication forks.

Further study of Purα and DSB repair revealed a remarkable inverse correlation between Purα expression and expression of the DSB repair protein Rad51.88 Rad51 plays a critical role in repairing DSBs by promoting homologous recombination-directed (HRR) DNA repair. Purα expression is gradually increased in brain tissue during development, reaching a peak stage at postnatal day 15.89 In this brain tissue, we found that Purα expression was dramatically increased at postnatal day 15, whereas Rad51 was reduced. Furthermore, Rad51 expression was increased in PURA+/− and PURA−/− MEFs, while introduction of ectopically expressed Purα reduced the level of Rad51 in PURA−/− MEFs. These results suggest that either Purα downregulates Rad51 expression or promotes Rad51 degradation.88 Another protein that can regulate Rad51 and HRR is the HIV-1 Tat protein, which upregulates the level of expression of Rad51 and increased repair of DNA DSBs by HRR in Tat-producing cells.90 As described above, HIV-1 Tat interacts physically and functionally with Purα. Co-expression studies with HIV-1 Tat and Purα indicated that HIV-1 Tat stimulated HRR DNA repair of DNA DSBs and the nuclear appearance of Rad51 foci, whereas Purα suppressed HRR DNA repair, Rad51 expression and Rad51 foci formation.88

In another study of Purα and DNA repair, cisplatin was used to inflict DNA damage.91 Cisplatin is a potent antitumor agent and exerts its effect via its interaction with DNA to produce cross-linked DNA adducts. Cells deficient in Purα exhibited an enhanced sensitivity to cisplatin as determined by assays for cell viability and clonogenicity. This was observed not only for the Purα-negative MEFs but also for a variety of human tumor cell types, including glioblastoma cells, that had been rendered depleted for Purα protein by an RNA interference approach employing treatment with an siRNA directed against Purα. MEFs that were negative for Purα also showed enhanced H2AX phosphorylation following treatment with cisplatin. Repair of a transfected cisplatin-treated reporter plasmid was also impaired in a reactivation assay using Purα-negative MEFs and the ability of nuclear extracts derived from Purα-negative MEFs to perform non-homologous end-joining DSB DNA repair in vitro was also ablated.91 Taken together, these findings indicate that Purα is both protective against DNA damage and also assists in DNA repair after DNA damage has occurred. It is thus possible that Purα downregulation may be a new therapeutic modality for cisplatin-resistant tumors.

Conclusions

The high degree of evolutionary conservation of Purα, its wide-spread expression in tissues of metazoans and its ability to bind to a broad range of nucleic acids and to different cellular proteins that have important regulatory functions, all indicate that Purα is a key player with multiple roles in cellular regulation. The ability of Purα to negatively regulate the cell cycle and cell proliferation and thus act as a tumor suppressor make it a possible therapeutic target for cancer therapy. On the other hand, Purα has a protective effect against cisplatin-induced DNA damage and enhances subsequent DNA repair, hence downregulation of Purα may be a new treatment avenue for cisplatin-resistant tumors. Given the importance of Purα in cell regulation, it is perhaps surprising that homozygous PURA knockout mice survive birth but only later succumb due to deficits in post-natal brain development. Perhaps, the other members of the Pur family of proteins, Purβ and Purγ can compensate for the lack of Purα in some of its cellular functions. In any event, the results from the PURA knockout mice highlight the importance of Purα in the post-synaptic dendrite as described above. This might have significance for certain neurodegenerative diseases. For example, fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) involves CGG trinucleotide repeats in the 5'-untranslated region (5' UTR) of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene and is marked by a pronounced dropout of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum and ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in both neurons and astrocytes throughout the brain. CGG repeats in RNA are binding sites for Purα and evidence from a Drosophila model has implicated sequestration of Purα by the FMR1 mRNA leading to neuronal cell death in the pathogenesis of this disease.92 Thus, overexpression of Purα suppressed rCGG-mediated neurodegeneration in a dose-dependent manner in the Drosophila model of FXTAS. Moreover, Purα was found to be present within the inclusion bodies induced by rCGG repeats in both Drosophila and FXTAS patients.92 In other studies, proteomic approaches have revealed that phosphorylated Purα is induced by normal exercise in the in the rat hippocampus93 while PURA was found to be one of eight validated genes showing differential expression in a comparison of 12,000 genes in Brodmann’s Area 46 (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) in bipolar I disorder and control samples.94 Thus, changes in Purα may be involved in the regulation of synaptic plasticity under both normal and pathological conditions and Purα may represent a potential target for neuropharmacological manipulation of synaptic plasticity.

Acknowledgements

We thank past and present members of the Center for Neurovirology for their insightful discussion and sharing of ideas and reagents. We also wish to thank C. Schriver for editorial assistance. This work was supported by grants awarded by the NIH to K.K.

References

- 1.Haas S, Gordon J, Khalili K. A developmentally regulated DNA-binding protein from mouse brain stimulates myelin basic protein gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3103–3112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas S, Thatikunta P, Steplewski A, Johnson EM, Khalili K, Amini S. A 39-kD DNA-binding protein from mouse brain stimulates transcription of myelin basic protein gene in oligodendrocytic cells. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1171–1179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergemann AD, Johnson EM. The HeLa Pur factor binds single-stranded DNA at a specific element conserved in gene flanking regions and origins of DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1257–1265. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergemann AD, Ma ZW, Johnson EM. Sequence of cDNA comprising the human pur gene and sequence-specific single-stranded-DNA-binding properties of the encoded protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5673–5682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma ZW, Bergemann AD, Johnson EM. Conservation in human and mouse Puralpha of a motif common to several proteins involved in initiation of DNA replication. Gene. 1994;149:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu H, Johnson EM. Distinct proteins encoded by alternative transcripts of the PURγ gene, located contrapodal to WRN on chromosome 8, determined by differential termination/polyadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2417–2426. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson EM. The Pur protein family: clues to function from recent studies on cancer and AIDS. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2093–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallia GL, Johnson EM, Khalili K. Puralpha: a multifunctional single-stranded DNA- and RNA-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3197–3205. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.17.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darbinian N, Gallia GL, Khalili K. Helix-destabilizing properties of the human single-stranded DNA- and RNA-binding protein Puralpha. J Cell Biochem. 2001a;80:589–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wortman MJ, Johnson EM, Bergemann AD. Mechanism of DNA binding and localized strand separation by Puralpha and comparison with Pur family member, Purbeta. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1743:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen NN, Khalili K. Transcriptional regulation of human JC polyomavirus promoters by cellular proteins YB-1 and Puralpha in glial cells. J Virol. 1995;69:5843–5848. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5843-5848.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krachmarov CP, Chepenik LG, Barr-Vagell S, Khalili K, Johnson EM. Activation of the JC virus Tat-responsive transcriptional control element by association of the Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus 1 with cellular protein Puralpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14112–14117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chepenik LG, Tretiakova AP, Krachmarov CP, Johnson EM, Khalili K. The single-stranded DNA binding protein, Pur-alpha, binds HIV-1 TAR RNA and activates HIV-1 transcription. Gene. 1998;210:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darbinian N, Sawaya BE, Khalili K, Jaffe N, Wortman B, Giordano A, et al. Functional interaction between cyclin T1/cdk9 and Puralpha determines the level of TNFalpha promoter activation by Tat in glial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2001c;121:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tretiakova A, Steplewski A, Johnson EM, Khalili K, Amini S. Regulation of myelin basic protein gene transcription by Sp1 and Puralpha: evidence for association of Sp1 and Puralpha in brain. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:160–168. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199910)181:1<160::AID-JCP17>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei Q, Miskimins WK, Miskimins R. Stage-specific expression of myelin basic protein in oligodendrocytes involves Nkx2.2-mediated repression that is relieved by the Sp1 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16284–16294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong T, Scully M, Shelley CS, Colgan SP. Identification of Puralpha as a new hypoxia response factor responsible for coordinated induction of the beta2 integrin family. J Immunol. 2007;179:1934–1941. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limesand SW, Jeckel KM, Anthony RV. Puralpha, a single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid binding protein, augments placental lactogen gene transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:447–457. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelley CS, Teodoridis JM, Park H, Farokhzad OC, Bottinger EP, Arnaout MA. During differentiation of the monocytic cell line U937, Puralpha mediates induction of the CD11c beta2 integrin gene promoter. J Immunol. 2002;168:3887–3893. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thatikunta P, Sawaya BE, Denisova L, Cole C, Yusibova G, Johnson EM, et al. Identification of a cellular protein that binds to Tat-responsive element of TGFbeta-1 promoter in glial cells. J Cell Biochem. 1997;67:466–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zambrano N, De Renzis S, Minopoli G, Faraonio R, Donini V, Scaloni A, et al. DNA-binding protein Puralpha and transcription factor YY1 function as transcription activators of the neuron-specific FE65 gene promoter. Biochem J. 1997;328:293–300. doi: 10.1042/bj3280293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Pedigo N, Shenoy S, Khalili K, Kaetzel DM. Puralpha activates PDGF-A gene transcription via interactions with a G-rich, single-stranded region of the promoter. Gene. 2005;348:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobretsova A, Johnson JW, Jones RC, Edmondson RD, Wight PA. Proteomic analysis of nuclear factors binding to an intronic enhancer in the myelin proteolipid protein gene. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1979–1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muralidharan V, Sweet T, Nadraga Y, Amini S, Khalili K. Regulation of Puralpha gene transcription: evidence for autoregulation of Puralpha promoter. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186:406–413. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2000)9999:999<000::AID-JCP1039>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlini LE, Getz MJ, Strauch AR, Kelm RJ., Jr Cryptic MCAT enhancer regulation in fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. Suppression of TEF-1 mediated activation by the single-stranded DNA-binding proteins, Puralpha, Purbeta and MSY1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8682–8692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knapp AM, Ramsey JE, Wang SX, Godburn KE, Strauch AR, Kelm RJ., Jr Nucleoprotein interactions governing cell type-dependent repression of the mouse smooth muscle alpha-actin promoter by single-stranded DNA-binding proteins Puralpha and Purbeta. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7907–7918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian SV, Polikandriotis JA, Kelm RJ, Jr, David JJ, Orosz CG, Strauch AR. Induction of vascular smooth muscle alpha-actin gene transcription in transforming growth factor beta1-activated myofibroblasts mediated by dynamic interplay between the Pur repressor proteins and Sp1/Smad coactivators. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4532–4543. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang A, David JJ, Subramanian SV, Liu X, Fuerst MD, Zhao X, et al. Serum response factor neutralizes Puralpha- and Purbeta-mediated repression of the fetal vascular smooth muscle alpha-actin gene in stressed adult cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:702–714. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00173.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darbinian N, Cui J, Basile A, Valle LD, Otte J, Miklossy J, et al. Negative Regulation of AbetaPP Gene Expression by Pur-alpha. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:71–82. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Da Silva N, Bharti A, Shelley CS. hnRNP-K and Pur(alpha) act together to repress the transcriptional activity of the CD43 gene promoter. Blood. 2002;100:3536–3544. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.10.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shelley CS, Da Silva N, Teodoridis JM. During U937 monocytic differentiation repression of the CD43 gene promoter is mediated by the single-stranded DNA binding protein Puralpha. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:159–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta M, Sueblinvong V, Raman J, Jeevanandam V, Gupta MP. Single-stranded DNA-binding proteins PURalpha and PURbeta bind to a purine-rich negative regulatory element of the alpha-myosin heavy chain gene and control transcriptional and translational regulation of the gene expression. Implications in the repression of alpha-myosin heavy chain during heart failure. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44935–44948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lasham A, Lindridge E, Rudert F, Onrust R, Watson J. Regulation of the human fas promoter by YB-1, Puralpha and AP-1 transcription factors. Gene. 2000;252:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penberthy WT, Zhao C, Zhang Y, Jessen JR, Yang Z, Bricaud O, et al. Puralpha and Sp8 as opposing regulators of neural gata2 expression. Dev Biol. 2004;275:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadakata T, Kuo C, Ichikawa H, Nishikawa E, Niu SY, Kumamaru E, et al. Puralpha, a single-stranded DNA binding protein, suppresses the enhancer activity of cAMP response element (CRE) Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;77:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim K, Choi J, Heo K, Kim H, Levens D, Kohno K, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel H1.2 complex that acts as a repressor of p53-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9113–9126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708205200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji J, Tsika GL, Rindt H, Schreiber KL, McCarthy JJ, Kelm RJ, Jr, et al. Puralpha and Purbeta collaborate with Sp3 to negatively regulate beta-myosin heavy chain gene expression during skeletal muscle inactivity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1531–1543. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00629-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson EM, Chen PL, Krachmarov CP, Barr SM, Kanovsky M, Ma ZW. Association of human Puralpha with the retinoblastoma protein, Rb, regulates binding to the single-stranded DNA Puralpha recognition element. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24352–24360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darbinian N, Gallia GL, Kundu M, Shcherbik N, Tretiakova A, Giordano A, et al. Association of Puralpha and E2F-1 suppresses transcriptional activity of E2F-1. Oncogene. 1999;18:6398–6402. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darbinian N, White MK, Gallia GL, Amini S, Rappaport J, Khalili K. Interaction between the Pur-alpha and E2F-1 transcription factors. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2585–2594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darbinian N, White MK, Khalili K. Regulation of the Pur-alpha promoter by E2F-1. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1052–1063. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safak M, Gallia GL, Khalili K. Reciprocal interaction between two cellular proteins, Puralpha and YB-1, modulates transcriptional activity of JCVCY in glial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2712–2723. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Itoh H, Wortman MJ, Kanovsky M, Uson RR, Gordon RE, Alfano N, et al. Alterations in Pur(alpha) levels and intracellular localization in the CV-1 cell cycle. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:651–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu H, Barr SM, Chu C, Kohtz DS, Kinoshita Y, Johnson EM. Functional interaction of Puralpha with the Cdk2 moiety of cyclin A/Cdk2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:851–857. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gallia GL, Safak M, Khalili K. Interaction of the single-stranded DNA-binding protein Puralpha with the human polyomavirus JC virus early protein T-antigen. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32662–32669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stacey DW, Hitomi M, Kanovsky M, Gan L, Johnson EM. Cell cycle arrest and morphological alterations following microinjection of NIH3T3 cells with Purα. Oncogene. 1999;18:4254–4261. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barr SM, Johnson EM. Ras-indcued colony formation and anchorage-independent growth inhibited by elevated expression of Purα in NIH3T3 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81:621–638. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Darbinian N, Gallia GL, King J, Del Valle L, Johnson EM, Khalili K. Growth inhibition of glioblastoma cells by human Pur(alpha) J Cell Physiol. 2001b;189:334–340. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruchova H, Borovanova T, Klamova H, Brdicka R. Gene expression profiling in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with hydroxyurea. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:1289–1295. doi: 10.1080/10428190290026358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lezon-Geyda K, Najfeld V, Johnson EM. Deletions of PURA, at 5q31, and PURB, at 7p13, in myelodysplastic syndrome and progression to acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 2001;15:954–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inoue T, Leman ES, Yeater DB, Getzenberg RH. The potential role of purine-rich element binding protein (PUR) alpha as a novel treatment target for hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Prostate. 2008;68:1048–1056. doi: 10.1002/pros.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang LG, Johnson EM, Kinoshita Y, Babb JS, Buckley MT, Liebes LF, et al. Androgen receptor overexpression in prostate cancer linked to Puralpha loss from a novel repressor complex. Cancer Res. 2008a;68:2678–2688. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berger JR. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:461–469. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khalili K, Gordon J, White MK. The polyomavirus, JCV, and its involvement in human disease. In: Ahsan N, editor. Polyomaviruses and Human Diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. Vol. 577. Georgetown TX: Landes Bioscience; 2006. pp. 274–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khalili K, Safak M, Del Valle L, White MK. JC virus molecular biology and the human demyelinating disease, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. In: Shoshkes Reiss C, editor. Neurotropic virus infections. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 190–211. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berger JR, Chauhan A, Galey D, Nath A. Epidemiological evidence and molecular basis of interactions between HIV and JC virus. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:329–338. doi: 10.1080/13550280152537193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Major EO, Amemiya K, Tornatore CS, Houff SA, Berger JR. Pathogenesis and molecular biology of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC virus-induced demyelinating disease of the human brain. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:49–73. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berger JR, Kaszovitz B, Post MJ, Dickinson G. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. A review of the literature with a report of sixteen cases. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:78–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-1-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berger JR. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome: explaining the high incidence and disproportionate frequency of the illness relative to other immunosuppressive conditions. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:38–41. doi: 10.1080/13550280390195261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berger JR, Concha M. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: The evolution of a disease once considered rare. J Neurovirol. 1995;1:5–18. doi: 10.3109/13550289509111006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gasnault J, Kahraman M, de Goer de Herve MG, Durali D, Delfraissy JF, Taoufik Y. Critical role of JC virus-specific CD4 T-cell responses in preventing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. AIDS. 2003;17:1443–1449. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Power C, Kong PA, Crawford TO, Wesselingh S, Glass JD, McArthur JC, et al. Cerebral white matter changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome dementia: alterations of the blood-brain barrier. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:339–350. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gallia GL, Houff SA, Major EO, Khalili K. Review: JC virus infection of lymphocytes—revisited. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1603–1609. doi: 10.1086/514161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Houff SA, Berger JR. The bone marrow, B cells and JC virus. J Neurovirol. 2008;16:1–3. doi: 10.1080/13550280802348222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marzocchetti A, Wuthrich C, Tan CS, Tompkins T, Bernal-Cano F, Bhargava P, et al. Rearrangement of the JC virus regulatory region sequence in the bone marrow of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J NeuroVirol. 2008;14:455–458. doi: 10.1080/13550280802356837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tada H, Rappaport J, Lashgari M, Amini S, Wong-Staal F, Khalili K. Trans-activation of the JC virus late promoter by the tat protein of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus in glial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3479–3483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chowdhury M, Taylor JP, Tada H, Rappaport J, Wong-Staal F, Amini S, et al. Regulation of the human neurotropic virus promoter by JCV-T antigen and HIV-1 tat protein. Oncogene. 1990;5:1737–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chowdhury M, Kundu M, Khalili K. GA/GC-rich sequence confers Tat responsiveness to human neurotropic virus promoter, JCVL, in cells derived from central nervous system. Oncogene. 1993;8:887–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Daniel DC, Wortman MJ, Schiller RJ, Liu H, Gan L, Mellen JS, et al. Coordinate effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protein Tat and cellular protein Puralpha on DNA replication initiated at the JC virus origin. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1543–1553. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-7-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ensoli B, Buonaguro L, Barillari G, Fiorelli V, Gendelman R, Morgan RA, et al. Release, uptake, and effects of extracellular human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein on cell growth and viral transactivation. J Virol. 1993;67:277–287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.277-287.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frankel AD, Pabo CO. Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1988;55:1189–1193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Daniel DC, Kinoshita Y, Khan MA, Del Valle L, Khalili K, Rappaport J, et al. Internalization of exogenous human immunodeficiency virus-1 protein, Tat, by KG-1 oligodendroglioma cells followed by stimulation of DNA replication initiated at the JC virus origin. DNA Cell Biol. 2004;23:858–867. doi: 10.1089/dna.2004.23.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gallia GL, Darbinian N, Tretiakova A, Ansari SA, Rappaport J, Brady J, et al. Association of HIV-1 Tat with the cellular protein, Puralpha, is mediated by RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11572–11577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wortman MJ, Krachmarov CP, Kim JH, Gordon RG, Chepenik LG, Brady JN, et al. Interaction of HIV-1 Tat with Puralpha in nuclei of human glial cells: characterization of RNA-mediated protein-protein binding. J Cell Biochem. 2000;77:65–74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000401)77:1<65::aid-jcb7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaminski R, Darbinian N, Sawaya BE, Slonina D, Amini S, Johnson EM, et al. Puralpha as a cellular co-factor of Rev/RRE-mediated expression of HIV-1 intron-containing mRNA. J Cell Biochem. 2008a;103:1231–1245. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson EM, Kinoshita Y, Weinreb DB, Wortman MJ, Simon R, Khalili K, et al. Role of Puralpha in targeting mRNA to sites of translation in hippocampal neuronal dendrites. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:929–943. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tretiakova A, Gallia GL, Shcherbik N, Jameson B, Johnson EM, Amini S, et al. Association of Puralpha with RNAs homologous to 7 SL determines its binding ability to the myelin basic protein promoter DNA sequence. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22241–22247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tiedge H, Fremeau RT, Jr, Weinstock PH, Arancio O, Brosius J. Dendritic location of neural BC1 RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2093–2097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ohashi S, Kobayashi S, Omori A, Ohara S, Omae A, Muramatsu T, et al. The single-stranded DNA- and RNA-binding proteins puralpha and purbeta link BC1 RNA to microtubules through binding to the dendrite-targeting RNA motifs. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1781–1790. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ohashi S, Koike K, Omori A, Ichinose S, Ohara S, Kobayashi S, et al. Identification of mRNA/protein (mRNP) complexes containing Puralpha, mStaufen, fragile X protein and myosin Va and their association with rough endoplasmic reticulum equipped with a kinesin motor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37804–37810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zeng LH, Fujimoto T, Kumamaru E, Irie Y, Miki N, Kuo CH. Characterization of novel Puralpha-binding proteins in mouse brain. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zeng LH, Okamura K, Tanaka H, Miki N, Kuo CH. Concomitant translocation of Puralpha with its binding proteins (PurBPs) from nuclei to cytoplasm during neuronal development. Neurosci Res. 2005;51:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kanai Y, Dohmae N, Hirokawa N. Kinesin transports RNA: isolation and characterization of an RNA-transporting granule. Neuron. 2004;43:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kobayashi Y, Suzuki K, Kobayashi H, Ohashi S, Koike K, Macchi P, et al. C9orf10 protein, a novel protein component of Puralpha-containing mRNA-protein particles (Puralpha-mRNPs): characterization of developmental and regional expressions in the mouse brain. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:723–731. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.950733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen N, Onisko B, Napoli JL. The nuclear transcription factor RARalpha associates with neuronal RNA granules and suppresses translation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20841–20847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802314200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kobayashi S, Agui K, Kamo S, Li Y, Anzai K. Neural BC1 RNA associates with puralpha, a single-stranded DNA and RNA binding protein, which is involved in the transcription of the BC1 RNA gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:341–347. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang H, Wang M, Reiss K, Darbinian-Sarkissian N, Johnson EM, Iliakis G, et al. Evidence for the involvement of Puralpha in response to DNA replication stress. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:596–602. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.4.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang H, White MK, Kaminski R, Darbinian N, Amini S, Johnson EM, et al. Role of Puralpha in the modulation of homologous recombination-directed DNA repair by HIV-1 Tat. Anticancer Res. 2008b;28:1441–1447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Khalili K, Del Valle L, Muralidharan V, Gault WJ, Darbinian N, Otte J, et al. Puralpha is essential for postnatal brain development and developmentally coupled cellular proliferation as revealed by genetic inactivation in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6857–6875. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6857-6875.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chipitsyna G, Slonina D, Siddiqui K, Peruzzi F, Skorski T, Reiss K, et al. HIV-1 Tat increases cell survival in response to cisplatin by stimulating Rad51 gene expression. Oncogene. 2004;23:2664–2671. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaminski R, Darbinyan A, Merabova N, Deshmane SL, White MK, Khalili K. Protective role of Puralpha to cisplatin. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008b;7:1926–1935. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.12.6938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jin P, Duan R, Qurashi A, Qin Y, Tian D, Rosser TC, et al. Puralpha binds to rCGG repeats and modulates repeat-mediated neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome. Neuron. 2007;55:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ding Q, Vaynman S, Souda P, Whitelegge JP, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise affects energy metabolism and neural plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus as revealed by proteomic analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1265–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nakatani N, Hattori E, Ohnishi T, Dean B, Iwayama Y, Matsumoto I, et al. Genome-wide expression analysis detects eight genes with robust alterations specific to bipolar I disorder: relevance to neuronal network perturbation. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1949–1962. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]