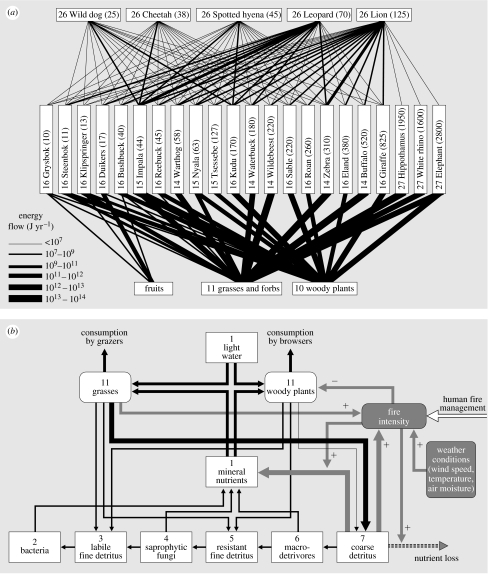

Figure 6.

The general framework for studying ecological networks (figures 1 and 2), as applied to the savannah ecosystem of Kruger National Park, South Africa. (a) The subweb of consumer–resource interactions that involves larger mammalian herbivores and their predators. The interaction topology and weights (presented here as annual energy flow, in J yr−1) for the herbivore–predator interactions is from the data presented by Owen-Smith & Mills (2008a), where feeding rates based on meat were converted to energy flows, using a conversion of 1 kg meat=23 600 J (Karasov & Martinez del Rio 2007). The energy flow (J d−1) between all plants and each herbivore population was first calculated allometrically as N×7940 W0.646 (Demment & van Soest 1985), where W is the body mass of the herbivore (g) and N is the population density, as reported by Owen-Smith & Mills (2008a). Then, this total energy flow per herbivore species was partitioned over its three main food item classes according to the proportional diets given by Gagnon & Chew (2000). (b) The interaction web for the same ecosystem based on physical and chemical interactions, detritus-based consumer–resource interactions, and interactions between organisms and abiotic (non-resource) conditions. The key process here is the role of fire, short-cutting nutrients away from the horizontal decomposition pathway (figure 2), making nutrients partly directly available to plants through burning off energy and carbon, while partly stimulating nutrient losses through ash run-off and gaseous losses. Also, fire kills (especially young) trees, while grasses are much more resistant to fire (Bond & Vanwilgen 1996). The higher coarse detritus production by grasses compared with trees increases the fuel loads, which promotes fires, benefiting grasses in competition with trees for light and water. On the other hand, if trees manage to outshade grasses during long fire intervals, then the fuel load is highly reduced, and fires become permanently suppressed. Also, high grazer densities can deplete grass biomass, which suppresses fires, and can lead to tree invasion (Dublin 1995; Sinclair 1995). This makes the outcome of the tree–grass interaction in grazed tropical systems at intermediate rainfall in the presence of fire highly unpredictable (Bond 2005), but very diverse in large herbivores (Olff et al. 2002). Quantitative interaction weights were not available for the interaction web shown in (b). Numbers inside each box indicate the trophic functional group (figure 2). See figure 1 for the interpretation of the different types of arrow.