Abstract

Purpose

Treatment of Legg–Calvé-Perthes disease in older children with greater involvement of the femoral head remains uncertain. Innominate, femoral or combined innominate and femoral osteotomies are generally performed to better contain and provide more coverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum with the objective of achieving a more spherical head and a congruent joint. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the radiographic outcomes of simultaneous femoral and pelvic osteotomies.

Methods

We reviewed the radiographic changes of 20 patients with Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease with a disease onset of over eight years of age who had undergone combined femoral and Salter innominate osteotomies. The hips in these 17 males and 3 females comprised 11 lateral pillar (LP) group B, 7 B/C, and 2 C. The patients were evaluated with a mean follow-up of five years and five months using the Stulberg radiographic assessment.

Results

Among those 20 hips, six became Stulberg II (SII), nine SIII, and five SIV. From the 11 LPB hips, five became SII, four SIII, and two SIV. The seven LPB/C turned out to be SII in one case, SIII in four, and SIV in two hips. One of the two LPC hips became SIII and the other one SIV. The three female patients had one LPB, one LPB/C, and one LPC hip, and surgery resulted in SIII hips in all three cases. Eight of these 20 cases were older than 11 years of age at the time of surgery, and all had fair or poor hips.

Conclusions

Simultaneous femoral and Salter innominate osteotomies in older children with a higher LP grouping can marginally improve the radiographic outcome in comparison with the natural history in LPB/C and LPC cases by converting a number of poor results to fair results.

Keywords: Legg–Perthes disease, Osteotomy, Pelvic bones, Femur, Surgery

Introduction

The objective of treatment in Legg–Calvé–Perthes (LCP) disease is to achieve a congruent mobile joint [1–7]. Surgical procedures to contain the femoral head in the acetabulum are generally considered the best form of treatment [1–11]. In children with more severe involvement (Herring types B and C), many surgeons prefer an osteotomy after six years of age [8–13].

There are several possibilities for the treatment of LCP disease in the older age group (more than ten years of age): varus femoral osteotomies, different pelvic osteotomies (Salter, Chiari, triple), and a combination of pelvic and femoral osteotomies (Salter with femoral shortening).

There is controversy over which type of osteotomy is most effective. Femoral varus osteotomy, with or without derotation, provides good containment in the early fragmentation stage and achieves spherical congruity when the head is centered in the acetabulum and remodeling potential is still present [9, 12, 13]. Containment with congruency between head and acetabulum in abduction and internal rotation should be confirmed before doing the osteotomy. This has been performed even after ten years of age [14]. The varus angle usually decreases with growth [15]. There is, however, the possibility of persisting varus and leg-length discrepancy and weakness in hip abductor power with a resultant limp [13, 16–18].

Pelvic osteotomy redirects the acetabulum, does not lead to shortening of the leg, but may increase pressure on the femoral head [10, 11, 19]. The commonly used Salter pelvic osteotomy can be combined with femoral varus osteotomy in cases of severe femoral head deformity that are not containable by pelvic or femoral osteotomy alone. It is used in older patients with laterally extruded, deformed, and larger femoral heads, and in those cases in which femoral or pelvic osteotomy alone would be predicted to fail to achieve adequate containment [20, 21]. We are reporting our experience with such a group of patients.

Materials and methods

We reviewed children with Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease that had been treated by simultaneous femoral and innominate osteotomies at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada, from 1988 to 2001. During this period, the plan for all of the >9-year-old patients in lateral pillar (LP) classes B, B/C, or C, at fragmentation stage, who showed signs of lateral subluxation of the femoral head or joint stiffness (<20° abduction and <10° internal rotation), was combined osteotomy.

Salter innominate osteotomy with threaded pin fixation was our preferred procedure on the pelvic side of the joint. The femoral osteotomy was varisation with the angle determined according to the best-fit position of the hip in abduction X-ray view. The osteotomy was fixed by a blade plate, and neck-shaft angles were never reduced to less than 105°.

Twenty patients (17 males, 3 females) had been treated with this regimen and they had all reached skeletal maturity at follow-up. All cases had lateral subluxation at the time of surgery, and the hip stiffness had been resolved before attempting the osteotomies. In fact, 13 patients underwent prior adductor release and three weeks of Petrie cast, and one received adductor tenotomy on the operating table before starting the osteotomy. The patients’ medical records were reviewed, all patients were assessed and the original radiographs evaluated using the modified LP classification [22]. The final follow-up radiographs was assessed by the Stulberg classification [7]. With an average follow-up of five years and five months (range, three years and seven months to eight years and six months), the radiographic changes were documented and the correlation of the original LP grouping with the final Stulberg class was sought and analyzed.

Results

The mean age of the 20 patients who received combined surgery was ten years (range, 8–13 years) at diagnosis and ten years and seven months (range, 9–13 years) at surgery.

Twenty hips—12 right, 8 left—that had combined osteotomy consisted of 11 LPB, 7 LPB/C, and 2 LPC cases (Table 1). Among those 20 hips, six had become Stulberg II (SII), nine SIII, and five SIV. No SI or SV hip was found in the follow-ups.

Table 1.

Outcomes (Stulberg scores) in each lateral pillar group LPB, B/C, and C

| SI | SII | SIII | SIV | SV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPB | 0 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| LPB/C | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| LPC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 0 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 20 |

LP, lateral pillar categories; SI, SII, SIII, SIV, SV, Stulberg classifications I, II, III, IV, V

The LP grouping had the following outcomes: in the 11 LPB hips, five became SII, four SIII, and two SIV (Fig. 1). The seven LPB/C turned out to be SII in one case, SIII in four, and SIV in two hips (Fig. 2). There were two LPC hips that converted to one SIII and one SIV in follow-up (Table 1). About half of the LPB hips and one out of seven LPB/C cases resulted in good hips (SI and SII), while the nine fair results (SIII hips) were mostly distributed among the LPB/C and LPC hips (Fig. 3). The main complication among this group was joint stiffness, observed in one case (SIV), who was treated by adductor tenotomy, arthrotomy and joint release. The rest of the cases had no stiffness or any other complication.

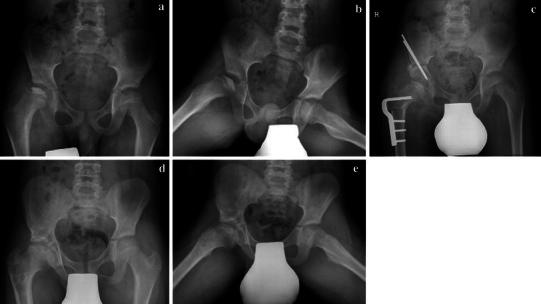

Fig. 1.

a, b Preoperative radiographs of a nine-year-old boy with group LPB left hip Legg–Calvé–Perthes. c After combined pelvic and femoral osteotomies. d, e Radiographs six years after surgery, showing a Stulberg II hip

Fig. 2.

a Preoperative radiographs of an 11-year-old boy, LPB/C left hip. b After combined osteotomy. c After four-year follow-up, with Stulberg III outcome

Fig. 3.

a, b Preoperative radiographs of a 9.5-year-old boy, LPB/C right hip. c After combined osteotomy. d, e After 4.5-year follow-up, with Stulberg III outcome

The three female patients had one LPB, one LPB/C and one LPC hip, and surgery resulted in SIII hips in all three cases. Increasing age resulted in worse Stulberg class. Those with surgery at 11 years of age and over (eight cases), or who were ten years of age or over at diagnosis (six cases), all became SIII or SIV at follow-up (Table 2).

Table 2.

The details for the 20 patients

| Patient | Age of diagnosis | Age at surgery | LP group | Follow-up/years + months | Stulberg class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 + 10 | 10 + 6 | C | 5 + 0 | IV |

| 2 | 9 + 7 | 9 + 10 | B | 6 + 6 | II |

| 3 | 13 + 0 | 13 + 1 | B | 4 + 8 | IV |

| 4 | 12 + 1 | 12 + 6 | B/C | 8 + 6 | III |

| 5 | 9 + 11 | 10 + 7 | B/C | 3 + 7 | III |

| 6 | 8 + 11 | 9 + 8 | B/C | 4 + 0 | III |

| 7 | 9 + 2 | 9 + 3 | B/C | 4 + 5 | II |

| 8 | 8 + 10 | 9 + 0 | B | 7 + 9 | III |

| 9 | 8 + 9 | 11 + 1 | B/C | 4 + 11 | III |

| 10 | 11 + 9 | 12 + 0 | B | 5 + 7 | IV |

| 11 | 12 + 2 | 12 + 3 | B | 5 + 6 | III |

| 12 | 10 + 10 | 11 + 3 | B | 4 + 2 | III |

| 13 | 9 + 11 | 11 + 2 | B/C | 4 + 6 | IV |

| 14 | 9 + 2 | 9 + 7 | B | 4 + 6 | II |

| 15 | 9 + 10 | 10 + 7 | B | 4 + 0 | II |

| 16 | 9 + 5 | 9 + 8 | B | 5 + 7 | III |

| 17 | 10 + 5 | 11 + 2 | C | 6 + 5 | III |

| 18 | 9 + 8 | 9 + 9 | B/C | 6 + 3 | IV |

| 19 | 8 + 0 | 9 + 0 | B | 6 + 0 | II |

| 20 | 8 + 6 | 9 + 0 | B | 5 + 10 | II |

Discussion

Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease in older children with a greater degree of head involvement and joint stiffness presents a therapeutic dilemma. The extent of head involvement and the age of disease onset are important prognosticators of final outcome [8]. Literature reports on nonsurgical treatment of children over nine years of age have been generally poor: Kamhi and MacEwen [2] had 91% poor results with noncontainment methods but 92% poor and fair results with containment bracing. Kelly et al. [3] and Ingman et al. [23] have reported poor results with noncontainment treatment in older children (54 and 87.5%). Kim et al. [24], using a new brace for treatment of Legg–Calvé–Perthes in 20 hips, had five cases over nine years of age who had LPA and LPB hips. There were still 40% poor results.

The multicenter study of Herring [25] in “over 8-year-old” children and with no surgery revealed 33% SI or SII, 37% SIII, 30% SIV–V. They pointed out that “children over the age of 9 years at the onset of the disease fared less well in response to various therapeutic approaches, and are the most difficult group to manage” [25]. In our study, with a smaller group and older patients, the number of poor results was less than for their nonsurgically treated patients.

The use of osteotomy as a containment method, in particular for higher LP classes, is well accepted by many surgeons [8–10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 20, 21, 25–29]. Femoral osteotomies, Salter innominate, Chiari, and triple pelvic osteotomies, and combination of pelvic and femoral osteotomies are the different containment surgical procedures used for older children with Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease.

We have no good explanation for the findings of Friedlander and Weiner [30]—40.5% good, 46% fair and 13.5% poor after varus femoral osteotomy in “over 9-year-old” patients—which were better results than ours. However, Noonan et al. [14], for a similar age group, had a higher incidence of poor results with varus osteotomy compared to our results with combined osteotomy (45% versus 25%).

Pelvic osteotomy, which redirects the acetabulum and provides improvement of femoral head coverage, has a shorter period of convalescence, and corrects the shortening caused by the disease, has been advocated [10, 26–28]. In studies comparing innominate and femoral osteotomies, Sponseller et al. [17] found no difference in children less than age 10 and poor results in those with onset over age 10 with either surgery, while Moberg et al. [29] observed the same clinical and radiographic results in femoral and innominate osteotomy groups but better coverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum in the innominate group. Ishida et al. [27] reported 17% good results on Salter innominate osteotomy in Catterall groups 3 and 4 on children older than seven years.

In Herring’s multicenter study [25], femoral or innominate osteotomy resulted in 50% SI–II, 32% SIII, and 18% SIV–V. Combined osteotomies were not one of the treatment options in that study. They concluded that LPB or LPB/C groups of patients benefited from osteotomy—pelvic or femoral, and surgery had no value in LPC cases.

Their osteotomy group, however, had more “good” Stulberg ratings than our combined pelvic and femoral osteotomies (50% versus 30%). Our combined osteotomy, however, changed the otherwise “poor” hips into “fair” hips. This might indicate that combined osteotomy improves the natural history in older patients (older than nine years) by changing a number of poor results into fair results. However, the findings in this older age group, reveal a trend toward better results with combined osteotomy, but not a statistically significant one. Combined surgery has been widely used to negate the increased intra-articular pressure elevation of innominate osteotomy and the shortening complication of femoral osteotomy when each is used alone [20, 21, 31, 32]. Olney and Asher [21] used it for nine cases of Catterall group III or IV in patients who had average age of eight years at disease onset. They reported four good, four fair, and one poor result using the Lloyd–Roberts grading [9]. They concluded that older patients who would otherwise require a neck-shaft varus angle of 110° or less for containment in the acetabulum were candidates for such a surgery. Crutcher and Staheli [32], in a report of cases of combined surgery, had 12 fair and two good results using the same evaluation system. Their radiological Stulberg evaluation, however, showed seven SII, six SIII, and one SIV hips. Their patients were 4–10 years old at diagnosis and eight years and four months at surgery. We had six SII, nine SIII, and five SIV hips. Our cases had fewer good hips compared to Crutcher and Staheli [32]. However, their cases were younger, with only five patients aged over nine years and none over 11 years at surgery. We had a slightly older population (10 years at diagnosis and 10.7 years at surgery), and used the more detailed and stringent modifications of LP classifications (adding group LPB/C) [22].

Triple pelvic osteotomy has also been used in older children to gain more acetabular rotation. However, the long-term results are not yet available [33, 34].

Lateral pillar grouping seems to be the more commonly accepted classification scheme for prognosis and decision-making for treatment, and it has good inter- and intraobserver reliability [22, 35]. Other attempts to find more reliable prognostic classifications, including determining a proximal growth plate index or formulating scores by combining clinical and radiologic factors, are also used [36, 37].

When the effect of age and degree of head involvement is evaluated, some improvement is observed in our study group over the results of Herring et al. [25], but only for B/C and C hips. Our LPB/C cases in comparison with their nonsurgical cases showed fewer poor hips, and we also obtained more “good” results in comparison with their surgical cases. The LPC cases again showed fewer poor results and more fair results in comparison with both their nonsurgical and surgical cases. The LPB hips, however, were similar to their nonoperated hips, and there were fewer “good” hips when compared with their osteotomy cases.

Conclusions

Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease in an >9-year-old child does not have a good outcome in obtaining a congruent hip. Combined pelvic and femoral osteotomies can improve the radiographic class of Stulberg grouping at skeletal maturity. However, this still does not still produce a congruent hip of SI or SII, but it does convert a poor result into a fair result. Therefore, the unsatisfactory outcome of a stiff hip for a higher Herring grouping in patients over nine years of age remains an unsolved problem.

References

- 1.Catteral A. The natural history of Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53:37–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamhi E, MacEwen GD. Treatment of Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:651–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly FB, Jr, Canale ST, Jones RR. Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. Long-term evaluation of non-containment treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez AG, Weinstein SL, Dietz FR. The weight-bearing abduction brace for the treatment of Legg–Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meehan PL, Angel D, Nelson JM. The Scottish rite abduction orthosis for the treatment of Legg–Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perpich M, McBeath A, Kruse D. Long-term follow-up of Perthes disease treated with spica cast. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3:160–165. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stulberg SD, Cooperman DR, Wallensten R. The natural history of Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:1095–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herring JA. Current concept review. The treatment of Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. A critical review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:448–458. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199403000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd-Roberts GC, Catteral A, Salaman PB. A controlled study of the indications for and the results of femoral osteotomy in Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:31–36. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B1.1270493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salter RB. Legg–Perthes disease. Part V. Treatment by innominate osteotomy. Instr Course Lect. 1973;22:309–316. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salter RB. Legg–Perthes disease: the scientific basis for the methods of treatment and their indications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;150:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Axer A, Gershuni DH, Hendel D, Mirovski Y. Indications for femoral osteotomy in Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;150:78–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canario AT, Williams L, Weintroub S, Catteral A, Lloyd-Roberts GC. A controlled study of the results of femoral osteotomy in severe Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62:438–440. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.62B4.7430219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noonan KJ, Price CT, Kupiszewski SJ, Pyevich M. Result of femoral varus osteotomy in children older than 9 years of age with Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirovski Y, Axer A, Hendel D. Residual shortening after osteotomy for Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:184–188. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B2.6707053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahiko K, Tadashi H, Hisashi I. Femoral varus osteotomy in Legg–Calve–Perthes disease: points at operation to prevent residual problems. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sponseller PD, Desai SS, Millis MB. Comparison of femoral and innominate osteotomies for the treatment of Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:1131–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moseley CF. The biomechanics of the pediatric hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 1980;11(1):3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rab GT. Biomechanical aspects of Salter osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;132:82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig WA, Kramer WG. Combined iliac and femoral osteotomies in Legg–Calve–Perthes syndrome. Presented at the forty-first annual meeting of The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Dallas, 17–22 January 1974. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:1299–1316. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olney BW, Asher MA. Combined innominate and femoral osteotomy for the treatment of severe Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5:645–651. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herring JA, Kim HT, Browne R. Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. Part I: classification of radiographs with use of the modified lateral pillar and Stulberg classifications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2103–2120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingman AM, Paterson DC, Sutherland AD. A comparison between innominate osteotomy and hip spica in the treatment of Legg–Perthes’ disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim WC, Hosokawa M, Kawamoto K, Chang K et al. (2006) Outcomes of new pogo-stick brace for Legg–Calve–Perthes’ disease. J Pediatr Orthop B 15:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Herring JA, Kim HT, Browne R. Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. Part II: prospective multicenter study of the effect of treatment on outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2121–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barer M. Role of innominate osteotomy in the treatment of children with Legg–Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;135:82–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishida A, Kuvajima SS, Filho JL, Milano C. Salter innominate osteotomy in the treatment of severe Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. Clinical and radiographic results in 32 patients (37 hips) at skeletal maturity. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:257–264. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson HJ, Jr, Putter H, Sigmond MB, et al. Innominate osteotomy in Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:426–435. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moberg A, Hansson G, Kaniklides C. Results after femoral and innominate osteotomy in Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;334:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedlander JK, Weiner D. Radiographic results of proximal varus osteotomy in Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:566–571. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asher M, Olney B. Management of severe Legg–Calve–Perthes disease with one-stage innominate and femoral osteotomy. Orthop Trans. 1984;8:457. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crutcher JP, Staheli LT. Combined osteotomy as a salvage procedure for severe Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:151–156. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar D, Bache CE, O’Hara JN. Interlocking triple pelvic osteotomy in severe Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:464–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poul J, Vejrostová M. Rotational acetabular osteotomy in the treatment of Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2001;68:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambandam SN, Gul A, Shankar R, Goni V. Reliability of radiological classifications used in Legg–Calve–Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:267–270. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamegaya M, Saisu T, Miura Y, Moriya H. A proposed prognostic formula for Perthes’ disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;440:205–208. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000180601.23357.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Domzalski ME, Inan M, Guille JT, Glutting J, Kumar J. The proximal femoral growth plate in Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;458:150–158. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180380ef2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]