Abstract

Background/Aims

We assessed twelve cases of suspected chronic pesticide intoxication, with medically unexplained physical symptoms.

Methods

Complete blood cell count (CBC), blood chemistry, routine urinalysis, chest X-ray, ECG, gastrofiberscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, neuroselective sensory nerve conduction threshold, and psychological assessment were performed on 12 farmers who believe themselves to have suffered from chronic pesticide intoxication.

Results

No specific abnormalities were observed on CBC, routine urinalysis, chest X-ray, ECG, gastroscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, or peripheral nerve conduction velocity test. They persistently manifested helplessness, depression, and anxiety. The results of both psychological assessment and general physical examination revealed the following clinical features: depression (8 cases), multiple chemical hypersensitivity syndrome (2 cases), alcoholism (1 case), and religious preoccupation (1 case).

Conclusion

In those living in the western rural area of South Korea, depression is a prominent ongoing presentation in pesticide-exposed farmers, in addition to unexplainable physical symptoms.

Keywords: Medically unexplained physical symptoms, Depression, Chronic pesticide intoxication, Farmers

INTRODUCTION

"Chronic pesticide poisoning" has often been marked as an etiology for vague symptoms of the neuromuscular system, and such vague phenomena make it difficult to differentiate pesticide poisoning from other etiologies, such as senile change and/or degenerative change. The symptoms seem to progress slowly, making it difficult to trace a particular process or progression of the symptoms1, 2). It is difficult to determine when the symptoms first started, and what factors caused and exacerbated them. Such unclear history leads doctors to hypothesize or surmise unlikely diagnoses.

"Chronic pesticide poisoning" refers to a constellation of symptoms possibly triggered by repeated exposure to agricultural chemicals over time. The current understanding and protocol for diagnosing of this kind of poisoning are ill.defined, sometimes resulting in hesitancy in parsing farmers into a clear cut category.

Farmers who seek medical attention for their symptoms are at times diagnosed with Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms (MUPS)3-5) or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome(CFS)6, 7). MUPS and CFS refer to disorders characterized primarily by debilitating fatigue, but accompanied by several other physical, constitutional, and neuropsychological complaints8). These diagnoses are commonly accompanied by, or even preceded by, neuropsychological complaints, somatic preoccupation, and/or depression8). Such patients are not provided with a well-defined scientific therapy or recommended a treatment for their symptoms.

However, the vague nature of the patients' complaints means they could be suffering from a wide range of other diagnoses. Therefore, close attention should be focused on these farmers, whose symptoms, at face value, lack a clear explanation.

This study summarizes the clinical features of the farmers who have visited the Institute of Pesticide Intoxication of Soonchunhyang University Hospital with MUPS, and who have been concerned about the possibility of chronic pesticide intoxication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

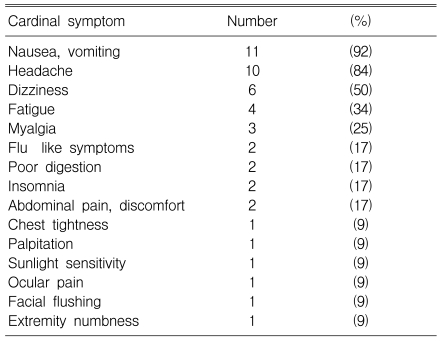

The target group was 12 patients in total (9 males, 3 females); ages ranged from 50 to 68 years (averaged 60.0±6.2 years); and academic background ranged from 0 to 12 years (averaged 7.6±3.6 years). All subjects visited the Institute during 2005-2006 from Chungnam and the neighboring province in the western rural area of South Korea, to see if their symptoms could be interpreted in the context of chronic pesticide intoxication. Patients were principally from the western rural section of the province because the Institute is easily accessible from that area. The farmers complained of various symptoms: nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache, fatigue, myalgia, and worries about chronic pesticide intoxication (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardinal symptoms of the subjects

In order to observe the clinical characteristics of potential chronic pesticide intoxication, we screened and selected the subjects looking for subjects that met the following criteria: history of applying a variety of insecticides and/or herbicides for more than 10 years, with regular use of organophosphate and carbamate compounds, on an area of at least 1 acre, approximately 5 times a year, with each spraying session lasting 2 to 3 hours. The latest pesticide exposure was less than a year. Any patient diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, chronic liver disease, cancer or psychiatric disease was excluded, because the multivariate systemic symptoms of these diseases might be difficult to differentiate from those of pesticide exposure. An intensive interview followed, specifically aimed at learning more about the subjects' farming history, the farm size they tended, their farming style (either manual or automatic), and their methods of pesticide application. Then, their height, weight, blood pressure, and temperature were measured. Personal disease history screening was performed on all the applicable subjects, and their physical characteristics were examined.

Blood samples were collected after overnight fasting. Routine urinalysis, blood chemistry (including blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, fasting glucose level, cholesterol, triglyceride, and serum electrolytes), chest X-ray, ECG, gastrofibroscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, and neuroselective sensory nerve conduction threshold were obtained in all cases. Neuroselective sensory nerve conduction threshold was evaluated in both the left and right middle fingers with an electro.diagnostic device by determining the current perception threshold (CPT) levels9, 10). Three independent CPT measures were obtained from each test site by using sinusoidal electrical stimuli at three different frequencies. These measures selectively quantify the functioning of three major subpopulations of sensory nerve fibers providing innervation to the test sites: large myelinated fibers (2000-Hz stimulation; cutaneous touch, pressure), small myelinated fibers (250-Hz stimulation; mechanoreceptive, pressure, temperature, fast pain), and small unmyelinated C.fibers (5-Hz stimulation; polymodal nociceptive, temperature, slow pain, postganglionic sympathetic). Patients with positive results were selected, and each consulted with a specialist such as an ophthalmologist or otolaryngologist, for headache, and a neurologist for dizziness or other neurological symptoms. The specialists performed additional tests related to their field, such as brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), before the diagnosis of MUPS was made (Figure 1).

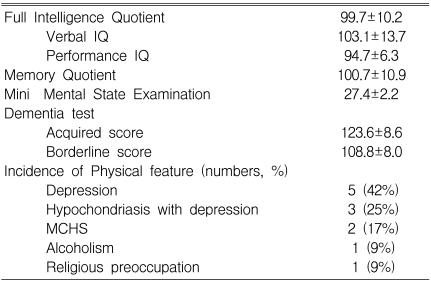

Psychological assessment and evaluation were performed by the specialists using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (K-WAIS)11), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)12), Bender Gestalt test13), projection-drawing tests14), Rey-Kim memory test15), Rorschach test16), Thematic Apperception Test17), and a Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)18). Criteria for diagnosis of multiple chemical hypersensitivity syndrome (MCHS) depended on the recommendations set by the American Academy of Environmental Medicine19).

RESULTS

The mean levels of hemoglobin (14.8±1.4 g/dL), hematocrit (43.9±4.4%), BUN (15.5±5.9 mg/dL), creatinine (0.97±0.10 mg/dL), fasting blood glucose (95.3±15.1 mg/dL), total cholesterol (180.9±34.7 mg/dL), triglyceride (164.5±21.8 mg/dL), alanine transaminase (33.1±6.9 unit/L), and aspartate transaminase (27.9±9.4 unit/L) were all in the normal range. The cholinesterase (7170.8±123.2 unit) and pseudocholinesterase levels (9774.3±122.1 unit) were also in normal range in all the cases.

No specific abnormalities were observed in routine urinalysis, chest X-ray, ECG, gastroscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, or peripheral nerve conduction velocity test. Cardinal symptoms and the final diagnosis of each subject are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Each subject's intelligence was in the general average range (FIQ 90~109). The psychological profile of the subjects was marked by the following traits: They were born and raised in the farming area and they lacked the cultural and educational benefit society provided; their oversensitivity about the smell of the agricultural chemicals led them into hypochondriacal somatic over-concern, leading to complaints of dizziness and nausea. Their ongoing mood was marked with helplessness, depression, and tendency toward anxiety.

Table 2.

Results of psychological assessment in the subjects

Psychological assessment and general physical examination found other clinical features to be depression (5 cases), hypochondriasis with depression (3 cases), MCHS (2 cases), alcoholism (1 case), and religious preoccupation (1 case) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

If considered as an epidemiological study, our observations could have an innate limitation. The number of the subjects was too small for proper statistical analysis to be undertaken and conclusion drawn from these cases. Moreover, there were no control groups available. Perhaps many other patients with depression, which might be related to chronic pesticide exposure, could have been treated in the psychological department.

The current study is rather a clinical observation than an epidemiological study. An interesting clinical trend demonstrated in this study was that the patients themselves hypothesized that they suffered from chronic pesticide intoxication. They, of their free will, chose to consult the Institute of Pesticide Poisoning instead of any other section or medical department.

In spite of the intensive diagnostic approaches to investigating their complaints, however, no obvious clinical evidence suggest that they had MUPS. MUPS is characterized by physical symptoms that prompt the sufferer to seek health care, but remain unsolved even after an appropriate medical evaluation. The prevalence and characteristics of MUPS may differ from society to society according to the influence of economical, cultural, and environmental background. Clinical literature20-26) has shown that MUPS and MCH are strongly and consistently associated with psychological distress and that they decrease quality of life and lead to depression and hypochondriasis.

However, when it comes to the pesticide.exposed farmers, it is impossible to know fully if their psychological characteristics are the result of chronic pesticide intoxication. There have been many reports suggesting that chronic pesticide exposure may cause both psychiatric and neurobehavioral symptoms1, 2). We did not diagnose the patients as victims of chronic pesticide intoxication while they continued to suspect that they were. Again, objective evidence is not enough to support their claim of being victims of such kind. Series of tests did not show that any of the symptoms could be attributed to chronic intoxication with farming chemicals. Evidence suggesting the association between the symptoms and chemical intoxication was lacking in these patients.

Recently, Beseler et al.27) reported that pesticide poisoning may contribute to the risk of depression. Psychoanalysis in our study suggested that the farmers had undergone significant distress due to stressful situations associated with farming. Even though they knew that chronic exposure to the chemicals was detrimental to their health, they had to carry on farming, bearing the risk of chronic chemical exposure. Such feelings of desperation and uneasiness may have exacerbated their day-to-day symptoms of headache, weakness, and poor digestion that ordinary people may have been able to avoid. The common psychological background in these cases was depression (8 of 12 patients). We could not pinpoint the actual causes of the depression, but the psychological status of farmers with MUPS could have been derived from the environmental situation described above.

Further research on the effects of long.term, low.level exposure to pesticides in farmers will be necessary to define the characteristics of MUPS, the psychological features, and neurobehavioral effects.

In conclusion, depression is a frequent feature of MUPS which implies that the farmers are under the influence of chronic pesticide exposure in the western rural area of South Korea.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the National Institute of Agricultural Science and Technology, Korea (grant of 2006-2007)

References

- 1.Roldan-Tapi L, Leyva A, Laynez F, Santed FS. Chronic neuropsychological sequelae of cholinesterase inhibitors in the absence of structural brain damage: two cases of acute poisoning. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:762–766. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moser VC, Phillips PM, McDaniel KL, Marshall RS, Hunter DL, Padilla S. . Toxicol Sci. 2005;86:375–386. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leiknes KA, Finset A, Moum T, Sandanger I. Methodological issues concerning lifetime medically unexplained and medically explained symptoms of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview: a prospective 11-year follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salmon P, Humphris GM, Ring A, Davies JC, Dowrick CF. Why do primary care physicians propose medical care to patients with medically unexplained symptoms?: a new method of sequence analysis to test theories of patient pressure. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:570–577. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000227690.95757.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen LA, Woolfolk RL, Escobar JI, Gara MA, Hamer RM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for somatization disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1512–1518. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.14.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengard B, Pedersen NL. Chronic widespread pain and its comorbidities: a population. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1649–1654. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyland ME, Sodergren SC, Lewith GT. Chronic fatigue syndrome: the role of positivity to illness in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. J Health Psychol. 2006;11:731–741. doi: 10.1177/1359105306066628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson RD, Engel CC., Jr Evaluation and management of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Neurologist. 2004;10:18–30. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000106921.76055.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurozawa Y, Nasu Y. Current perception thresholds in vibration-induced neuropathy. Arch Environ Health. 2001;56:254–256. doi: 10.1080/00039890109604450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takekuma K, Ando F, Niino N, Shimokata H. Age and gender differences in skin sensory threshold assessed by current perception in community-dwelling Japanese. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(1 supple):S33–S38. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.1sup_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iverson GL, Mendrek A, Adams RL. The persistent belief that VIQ-PIQ splits suggest lateralized brain damage. Appl Neuropsychol. 2004;11:85–90. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1102_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West SK, Friedman D, Munoz B, Roche KB, Park W, Deremeik J, Massof R, Frick KD, Broman A, McGill W, Gilbert D, German P. A randomized trial of visual impairment interventions for nursing home residents: study design, baseline characteristics and visual loss. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10:193–209. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.3.193.15081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy J, Rabinowitz D, Habib M, Goldman H, Miley D, Stefanyshyn HY, Freeman S, Murray T, Clauselle R. Bender Gestalt Recall as a measure of short-term visual memory in children and adolescents with psychotic and other severe disorders. Percept Mot Skills. 2002;95:1233–1238. doi: 10.2466/pms.2002.95.3f.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hecht H. Regularities of the physical world and the absence of their internalization. Behav Brain Sci. 2001;24:608–617. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x01000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Min SK, Moon IW, Ko RW, Shin HS. Effects of transdermal nicotine on attention and memory in healthy elderly non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2001;159:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s002130100899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The status of the Rorschach in clinical and forensic practice: an official statement by the Board of Trustees of the Society for Personality Assessment. J Pers Assess. 2005;85:219–237. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8502_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hibbard S, Mitchell D, Porcerelli J. Internal consistency of the object relations and social cognition scales for the Thematic Apperception Test. J Pers Assess. 2001;77:408–419. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinsoneault TB. Detecting random, partially random, and nonrandom Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-Adolescent protocols. Psychol Assess. 2005;17:476–480. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Academy of Allergy and Immunology. Idiopathic environmental intolerances. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spinhoven P, Verschuur M. Predictors of fatigue in rescue workers and residents in the aftermath of an aviation disaster: a longitudinal study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:605–612. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000222367.88642.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kisely S, Simon G. An international study comparing the effect of medically explained and unexplained somatic symptoms on psychosocial outcome. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamberg L. New mind/body tactics target medically unexplained physical symptoms and fears. JAMA. 2005;294:2152–2154. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.17.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caress SM, Steinemann AC. A national population study of the prevalence of multiple chemical sensitivity. Arch Environ Health. 2004;59:300–305. doi: 10.3200/aeoh.58.6.300-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullen MR. The worker with multiple chemical sensitivities: an overview. Occup Med. 1987;2:655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailer J, Witthoft M, Paul C, Bayerl C, Rist F. Evidence for overlap between idiopathic environmental intolerance and somatoform disorders. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:921–929. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000174170.66109.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giardino ND, Lehrer PM. Behavioral conditioning and idiopathic environmental intolerance. Occup Med. 2000;15:519–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beseler C, Stallones L, Hoppin JA, Alavanja MC, Blair A, Keefe T, Kamel F. Depression and pesticide exposures in female spouses of licensed pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study cohort. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:1005–1013. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000235938.70212.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]