Abstract

Background

Foreign objects in the gastrointestinal tract are usually the result of accidental swallowing. Yet foreign object ingestion is often seen in prisoners who mainly desire to leave prison. We report here on a series of 33 Korean prisoners with foreign object ingestion and they were treated endoscopically or surgically.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of 33 Korean prisoners (52 episodes) who were admitted due to ingestion of foreign objects between January 1998 and June 2004 to Konyang University Hospital and Gyeongsang National University Hospital.

Results

All the patients were male with a mean age of 35 years. The most common duration from ingestion to the visit to the ER was within 24 hours (25/52 episodes). Most of the foreign objects were located in the esophagus (42.3%) and stomach (42.3%). The number of foreign objects was one in 28 episodes, two in 12 episodes and three or more in twelve episodes. The most common foreign objects were metal wires (26/52 episodes). The mean size of the foreign objects was 11.9 centimeters long. Successful endoscopic treatment was performed in most patients (46/52 episodes, 88.5%). The remaining six cases were treated surgically.

Conclusions

The foreign objects in prisoners were a variety of unusual things because of the prison environment, and endoscopy is a mainstay of treatment for foreign object removal in Korean prisoners.

Keywords: Foreign object, Prisoner

INTRODUCTION

Foreign objects in the gastrointestinal tract are usually produced by accidental swallowing, but these objects rarely produce symptoms. Although most foreign objects are passed spontaneously, 10~20% of these patients need treatment1), and approximately 1% will require surgery2). Foreign objects greater than 2 cm in diameter or 5 cm in length are at risk for impaction3). Lymphadenopathy, viral hepatitis, foreign body insertion into the gastrointestinal tract, dental caries and pulmonary tuberculosis are known to be the principal nonpsychiatric and nonobstetrical diagnoses of prison inmates4). Foreign object ingestion is often seen in prisoners who are usually attempting to temporarily escape justice5). There have been several reports regarding foreign objects in prisoners6-10). We report here on a series of 33 Korean prisoners who ingested foreign objects and these patients were managed via endoscopy or surgery. This is the first report for foreign objects in Korean prisoners.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the medical records and endoscopic findings of 33 prisoners (52 episodes) who were admitted due to ingestion of foreign objects between January 1998 and June 2004 to either Konyang University Hospital or Gyeongsang National University Hospital. We investigated the time interval between foreign object ingestion and the visit to the ER, the locations, kinds and sizes of foreign objects, the methods of foreign object removal, complications of endoscopic management and the combined disorders of the prisoners. All the patients were evaluated within 48 hours of admission or at the initial presentation of foreign object ingestion and these patients were followed until elimination or removal of the foreign objects.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patients

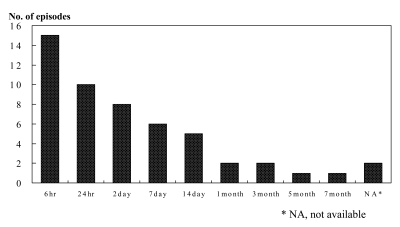

There were 52 episodes of foreign object ingestions among 33 prisoners. Twelve prisoners ingested foreign object more than once. The mean number of times of ingestion was 1.6 episodes per prisoner. The most frequent ingestion was four times each in two prisoners, respectively. All the patients were male, and their mean age was 35 years with a range of 25~50 years. The most common time interval from ingestion to visiting the ER was within 24 hours (25/52 episodes) (Figure 1). One prisoner did not visit the ER until seven months after ingestion of two metal wires. The foreign bodies were found in the ileum on surgery. Information about criminal charges was not available for all the patients.

Figure 1.

The Time Duration from Ingestion to Visit to ER. The most common time interval is within 6 hours.

Characteristics of the Foreign Objects

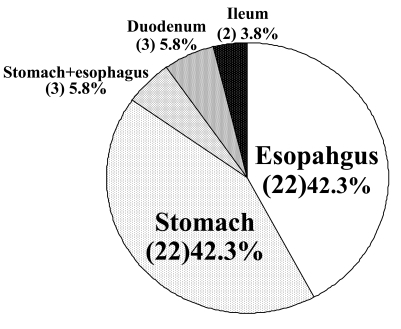

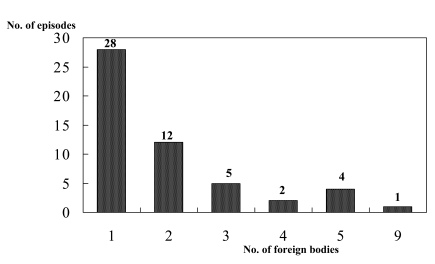

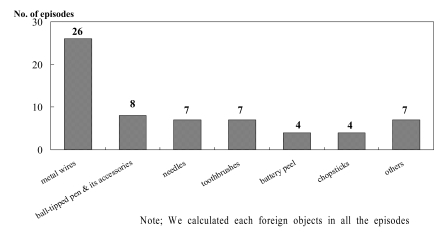

Most of the foreign objects were located in the esophagus (42.3%) and stomach (42.3%) (Figure 2). The number of foreign bodies was one in 28 episodes, two in 12 episodes, three in five episodes, four in two episodes, five in four episodes and even nine twisted wires in one episode (Figure 3). The common foreign objects included metal wires (26/52 episodes), ball-tipped pens and their accessories (8/52), toothbrushes (7/52), needles (7/52) and so on (Figure 4). The mean size of the foreign objects was 11.9 centimeters long (4~20). The most common size was between 10 and 15 centimeters in 38.5% of the episodes (20 episodes). The largest foreign object was a wire with a length of 25 centimeters.

Figure 2.

The Site of Foreign Objects Found. The most common site of foreign bodies found are the esophagus and the stomach.

Figure 3.

The Number of Foreign Objects. Over the half of the episodes, the number of foreign body is one.

Figure 4.

The Kind of Foreign Objects. The most common foreign body is the metal wires.

Management of Foreign Objects

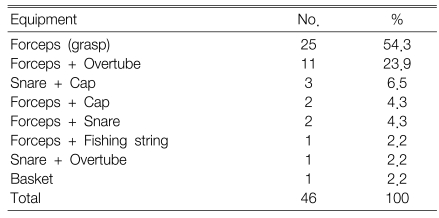

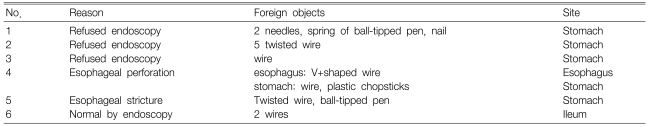

Successful endoscopic treatment was performed in most patients (46/52 episodes, 88.5%). The devices for removing the foreign objects were grasping forceps (rat.tooth or alligator tooth forceps) in 25/46 episodes (54.3%), grasping forceps combined with an overtube in 11 episodes (23.9%) and a snare with banding cap in three episodes (6.5%) (Table 1). The remaining six patients were treated surgically; three patients refused endoscopic treatment, one patient had esophageal stricture, one patient had esophageal perforation due to a V-shaped metal wire and the last prisoner underwent endoscopy, but we could not find a foreign object in the endoscopic field (Table 2).

Table 1.

The devices used for removal of foreign objects

Table 2.

Analysis of the surgically managed cases

Complications and Combined Disorders

The overall complication rate was 11.5% (6/52 episodes) and combined disorders were found in 21.2% (7/33 cases) of the patients. Complications after endoscopic removal were esophageal lacerations (four cases), esophageal perforation (one case) and acute hemorrhagic gastritis (one case). The combined disorders included personality disorders for five prisoners, schizophrenia for one patient and seizure disorder for one patient. The last prisoner was a 50 year-old male who had ingested a 4.5 centimeter.long needle during a seizure attack.

DISCUSSION

The majority of foreign object ingestions occur in the pediatric population with a peak incidence between six months and six years of age. In adults, true foreign object ingestion more commonly occurs among those patients with psychiatric disorders, mental retardation or impairment caused by alcohol, and those seeking some secondary gain with access to a medical facility11). Among prison inmates, deliberate foreign object ingestion is usually done to obtain an advantage that occurs secondary to the stated or real illness and it is not done with a suicidal intent. The most common secondary gains are temporary release from jail for treatment in a hospital or, in drug addicts, gaining access to narcotic analgesia. In our study, all the patients except one prisoner intentionally ingested foreign objects, and they achieved their secondary gains. Some reports have suggested that deliberate ingestion of foreign objects by prisoners appears to indicate severe psychiatric impairment and it is associated with particularly violent, impulsive behavior10). All the patients with foreign body ingestion should be consulted to a psychiatric physician. Yet in most cases, however, this is not always possible because of the patients' refusal.

In the general population, the most common ingested foreign bodies are coins in children12) and impacted meat or other types of food bolus in adults2). But for prison inmates in foreign countries, the common foreign objects are razor blades, metallic stars, toothbrushes, radio antennae and so on6-10, 13-15).

The common foreign objects in Korean prisoners were wires, ball.tipped pens and their accessories, needles and toothbrushes. Wires can be obtained from the metal protector of electronic fans in the prison or from the workplace. These ingested objects are different from those of other countries because of the different prison environment in Korea. Also, the prisoners ingested unusual things for secondary gains.

The rate of hospitalization for specifically treating foreign body ingestion in the gastrointestinal tract was 23 times greater for male prisoners than for male non.prisoners and 260 times greater for female prisoners than for female non.prisoners4).

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was a useful and effective method for making the diagnosis and treatment of foreign objects in prisoners, as well as for the general population in most cases. Grasping forceps were the most commonly used devices for the removal of foreign object. We used various devices for removing the foreign objects ingested by prisoners. Prevention of ingestion may be the best approach for treatment. Rada and James16) reported success with using behavioral modification and refraining from discussing incidents to reduce the frequency of similar actions among prisoners. Some efforts to improve the prison environment may also be necessary.

In summary, the foreign objects in prisoners were a variety of unusual things because of the prison environment and the secondary gains of the prisoners. Upper endoscopy was a useful and effective method for making the diagnosis and treating foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract in most cases.

References

- 1.Davidoff E, Towne JB. Ingested foreign bodies. N Y State J Med. 1975;75:1003–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telford JJ. Management of ingested foreign bodies. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:599–601. doi: 10.1155/2005/516195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krupp LB, Gelberg EA, Worsmer GP. Prisoners as medical patients. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:859–860. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.7.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady PG. Esophageal foreign bodies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:691–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT. Gastrointestinal "crosses": an indication for surgery. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:310–314. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaho KE, Merigian KS, Winbery SL, Park LJ, Cockrell M. Foreign body ingestions in the emergency department: case reports and review of treatment. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(97)00229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT, Losanoff HE. Oesophageal "crosses": a sinister foreign body. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14:54–55. doi: 10.1136/emj.14.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vassilev BN, Kazaandziev PK, Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT, Yordanov DE. Esophageal 'stars': a sinister foreign body ingestion. South Med J. 1997;90:211–214. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karp JG, Whiteman L, Convit A. Intentional ingestion of foreign objects by male prison inmates. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1991;42:533–535. doi: 10.1176/ps.42.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Faigel DO, Goldstein JL, Johanson JF, Mallery JS, Raddawi HM, Vargo JJ, 2nd, Waring JP, Fanelli RD, Wheeler-Harbough J. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:802–806. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng W, Tam PK. Foreign-body ingestion in children: experience with 1265 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1472–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaio E, Marioni G, Bruzon-Delgado J, Marchese-Ragona R, Staffieri A. Esophageal foreign body in a prison inmate: genuine suicide attempt or pursuit of illness for secondary gain? J Otolaryngol. 2005;34:220–222. doi: 10.2310/7070.2005.04042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW. Razor blade "ingestion": look behind the film. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:194–195. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200308000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner BC. Ingestion of foreign objects. Lancet. 2001;357:1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rada RT, James W. Urethral insertion of foreign bodies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:423–429. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290040033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]