Summary

Although primary tumours of the parapharyngeal space are rare and account for only 0.5% of head and neck neoplasms, they represent a formidable challenge to the surgeon both in the assessment of the preoperative condition and the appropriate surgical approach. This study is a retrospective review of the clinical records of 12 patients (8 male, 4 female, mean age 49 years), treated for parapharyngeal space tumours by the same surgical team from 1992 to 1998 and observed at follow-up for at least 10 years. Of these, 8 (66.6%) were benign and 4 (33.4%) malignant. Magnetic resonance imaging and fine-needle aspiration biopsy were performed as the preoperative evaluation in 8/12 cases. The positive predictive value of our fine-needle aspiration biopsy was 75% for benign tumours (3/4) and 100% (4/4) for malignant tumours. Different surgical approaches were used: transcervical-transmandibular in 5 cases (41.6%); transparotid-transcervical in 4 patients (33.4%); transoral in 2 patients (16.6%) with a small pleomorphic adenoma of the deep lobe of parotid, and in the last case (8.4%), transcervical surgery was performed for papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis. Post-operative complications occurred in 3/12 patients: two developed Horner’s syndrome and one patient presented a temporary marginal mandibular of facial nerve dysfunction. Post-operative radiotherapy was performed in 3/4 patients on account of malignancy. Each patient underwent a follow-up protocol of clinical controls and ultrasonography every 6 months, computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging once a year for 10 years. Eleven patients (91.4%) were still disease free after 10-year follow-up. One patient with a recurrent parotid gland adenocarcinoma died of distant metastasis 4 years after parapharyngeal space surgery. These 12 parapharyngeal space tumours were treated with use of one of the various surgical approaches described in relation to the histopathological diagnosis (benign or malignant), to the side (prestyloid or poststyloid) and to the size (±4 cm) of the neoplasia and, moreover, were observed at long-term follow-up. Results of personal experience in the treatment of the tumours of the parapharyngeal space confirm the necessity to follow a careful preoperative diagnostic outline that must be taken advantage of the study for imaging (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging) and of cytology, in order to plan surgical treatment with a safe approach and that reduces complications, aesthetic-functional damages and risk of recurrence.

Keywords: Parapharyngeal space, Parapharyngeal tumour, Parotid, Pleomorphic adenoma, Surgical approach, Mandibulotomy

Riassunto

Sebbene i tumori primitivi dello spazio parafaringeo (TSP) siano rari, rappresentando solo lo 0,5% delle neoplasie cervico-facciali, essi costituiscono una vera sfida per il chirurgo, sia per le difficoltà della stadiazione preoperatoria che per la scelta del corretto approccio chirurgico. Lo studio è una analisi retrospettiva di 12 pazienti (8 maschi e 4 femmine, età media 49 anni), trattati per tumori dello spazio parafaringeo da parte dello stesso team chirurgico dal 1992 al 1998 e seguiti nel follow-up per almeno 10 anni. Otto (66,6%) erano tumori benigni e 4 (33,4%) maligni. La valutazione preoperatoria basata su Risonanza Magnetica e citologia agoaspirativa è stato attuato in 8/12 casi. Il valore preditivo dell’agoaspirato è stato dell’87,5 globalmente, del 75% per i tumori benigni (3/4) e del 100% (4/4) per quelli maligni. Gli approcci chirurgici utilizzati sono stati i seguenti: transcervicale-transmandibolare in 5 casi (41,6%); transparotideo-transcervicale in 4 pazienti (33,4%) affetti da tumori prestiloidei inferiori a 4 cm del lobo profondo della parotide; transorale in 2 pazienti (16,6%) con un piccolo adenoma pleomorfo del lobo profondo della parotide; in un solo caso di metastasi da carcinoma papillifero della tiroide è stato praticato un approccio transcervicale. Le complicanze postoperatorie si sono manifestate in 3/12 pazienti: 2 casi di sindrome di Horner ed un caso di deficit del ramo marginalis del facciale. La radioterapia post-operatoria è stata effettuata in 3 dei 4 pazienti affetti da neoplasia maligna. Il protocollo del follow-up prevedeva per ogni paziente uno studio ecografico ogni 6 mesi e uno studio con Tomografia Computerizzata o Risonanza Magnetica una volta l’anno per 10 anni. Undici pazienti (91,4%) sono risultati vivi liberi da malattia a 10 anni dal trattamento. Un paziente affetto da adenocarcinoma recidivo della parotide è deceduto per metastasi a distanza di 4 anni dopo la chirurgia. La scelta dei diversi approcci chirurgici è stata effettuata in base alla diagnosi istopatologica di natura, alla sede (pre o post stiloidea) ed alle dimensioni (±4 cm) della neoplasia. I risultati della nostra esperienza nel trattamento dei tumori dello spazio parafaringeo confermano la necessità di seguire una accurata strategia preoperatoria per poter pianificare il trattamento chirurgico più appropriato a garantire l’asportazione radicale della neoplasia, riducendo nel contempo le complicanze, i deficit estetico funzionali ed il rischio di recidive.

Introduction

Although primary tumours of the parapharyngeal space (PPS) are rare and account for only 0.5% of head and neck neoplasms, the anatomy of the PPS makes clinical examination very difficult 1. Therefore, any neoplasms which form in this area present a formidable challenge to the surgeon both in the assessment of the preoperative condition and the appropriate surgical approach.

The PPS is an inverted pyramid-like area which starts at the base of the skull with the apex reaching the greater cornu of the hyoid bone. The boundaries of the space are: the temporal bone above, the vertebrae and prevertebral muscles behind, the buccopharyngeal fascia (which covers the pharyngobasilar plane and the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle) medially and laterally both the condyle of the mandible and the medial pterygoid muscle. This space is divided into the prestyloid and poststyloid compartment by thick layers of fascia extending from the styloid process to the tensor–vascular–styloid fascia which is comprised by the tensor veli palatine muscle, its fascia, the stylopharyngeal and the styloglossus muscles 2 3.

Tumours which develop in these spaces may originate from any of the structures normally occupying these compartments. The retromandibular portion of the parotid gland and its lymph nodes and adipose tissue are found in the prestyloid space, while the internal carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, the IX, X, XI and XII cranial nerves, the sympathetic chain and the lymph nodes of the oral cavity, oropharynx, paranasal sinuses and the thyroid gland are in the poststyloid area.

The PPS pathologies most commonly found are primary tumours (both benign and malignant), metastatic lymph nodes and involvement from lymphoproliferative diseases and adjacent site tumours which extend into this space 1 4. In the prestyloid space, salivary gland neoplasms (especially parotid gland pleomorphic adenomas) are the most common, while neurogenic tumours (e.g. schwannomas and neurofibromas) are those most commonly affecting the poststyloid. Of these tumours, only 20% are malignant and 50% originate either in the deep lobe of the parotid gland or the minor salivary glands 5. Other less common neoplasms include: neurogenic tumours (13%), vascular tumours (paragangliomas), chordomas, lypomas, lymphomas, chemodectomas, rhabdomyomas, chondrosarcomas, desmoid tumours, ameloblastomas, amyloid tumours, ectomesenchymomas, fibrosarcomas and plasmocytomas.

PPS tumours usually display very few symptoms: sometimes a neck mass is present but usually intraorally they appear as a smooth submucosal mass displacing the lateral pharyngeal wall, tonsils and soft palate antero-medially.

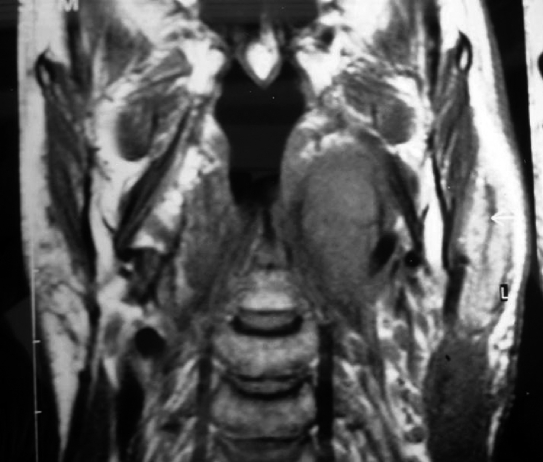

Imaging studies are used to predict the origin, location and the size of parapharyngeal tumours. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1A) with gadolinium, is better than a computed tomography (CT) scan and is the examination of choice. Angiography is recommended for all enhancing lesions or vascularised masses, particularly if imaging shows a widening of the carotid bifurcation.

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is accurate in 90-95% of cases. It is performed transorally, transcervically or guided by CT or ultrasound (US) and can predict the nature of the lesion which will assist surgeon-patient planning 6 7.

The surgical removal of these tumours is the best treatment. Surgical resection techniques described in the literature 5 8–10 are classified as transoral, transcervical, transparotid–transcervical, transcervical–transmandibular or infratemporal and the correct choice between them depends upon the accurate information on mass size and location, its relationship with the surrounding vessels and nerves and its nature 11.

Personal experience is presented in the diagnosis and treatment of PPS tumours, disease evaluation and control, post-operative complications and the need for mandibulectomy associated with a transcervical approach for tumour removal, after 10 years or more follow-up.

Patients and methods

This study is a retrospective review of the clinical records of 12 patients treated for PPS tumours from 1992 to 1998 by the same surgical team (directed by Francesco Marzetti) at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery of Regina Elena National Cancer Institute of Rome, Italy and followed up for at least 10 years.

The study population comprised 8 males and 4 females with a mean age of 49 (range 23–74 years) affected by parapharyngeal mass tumours.

The preoperative protocol was based on: a) imaging study to establish site, size and anatomical relationships. CT was performed in 4 cases, MRI in 7 and both in one case; b) FNAC US or CT guided, performed to determine the nature of the mass. Of these 12 patients, 8 underwent the procedure, while 2 patients refused and in 2 cases of recurrent pleomorphic adenoma it was deemed unnecessary.

The surgical approach, in these 12 PPS tumours, was: transoral in 2 patients with pleomorphic adenoma of 3 cm which caused a swelling in the tonsil region; transparotid-transcervical in 4 cases with benign tumours of the prestyloid space and < 4 cm in size; transmandibular in 5 cases with malignant tumour or neoplasm > 4 cm in size. In one case of papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis, 4 cm in size and with limited cranial extension, a transcervical approach was performed.

All patients were observed at annual follow-up for at least 10 years, with a physical examination and imaging evaluation (US, CT or MRI). The clinical and pathological characteristics of patients are shown in Tables I and II.

Table I. Preoperative data of the 12 patients studied.

| N. | Sex/Age (yrs) | Year of treatment | Histopathology | Site | Size (cm) | Imaging | FNAC |

| 1 | M/23 | 1992 | Pleomorphic adenoma | Prestyloid | 3 | CT | Yes |

| 2 | F/53 | 1994 | Pleomorphic adenoma | Prestyloid | 3 | CT | Yes |

| 3 | F/44 | 1995 | Pleomorphic adenoma | Prestyloid | 4 | MRI | No |

| 4 | M/28 | 1996 | Pleomorphic adenoma | Prestyloid | 10 | CT | Yes |

| 5 | M/50 | 1996 | Pleomorphic adenoma | Prestyloid | 4 | CT | Yes |

| 6 | M/39 | 1997 | Recurrent adenocarcinoma | Prestyloid | 5 | CT/MRI | Yes |

| 7 | M/74 | 1997 | Pleomorphic adenoma | Prestyloid | 4 | MRI | No |

| 8 | M/59 | 1997 | SCC metastasis | Retrostyloid | 3 | MRI | Yes |

| 9 | F/37 | 1997 | Rec. pleomorphic adenoma | Prestyloid | 4 | MRI | No |

| 10 | F/66 | 1997 | Rec. pleomorphic adenoma | Retrostyloid | 6 | MRI | No |

| 11 | M/47 | 1998 | SCC | Prestyloid | 3 | MRI | Yes |

| 12 | M/66 | 1998 | Met. thyroid papillary ca. | Retrostyloid | 4 | MRI | Yes |

Table II. Surgical approach, complications and follow-up of the 12 patients.

| N. | Surgical approach | Complications | Follow-up (yrs) | Result |

| 1 | Transoral | No | 16 | Alive NED |

| 2 | Transoral | No | 14 | Alive NED |

| 3 | Transparotid-transcervical | No | 13 | Alive NED |

| 4 | Transcervical transmandibular with double osteotomy | Temporary marginal mandibular dysfunction | 12 | Alive NED |

| 5 | Transparotid-transcervical | No | 12 | Alive NED |

| 6 | Transcervical transmandibular with "swing" approach | No | 4 | Died of disease |

| 7 | Transparotid-transcervical | No | 10 | Died NED |

| 8 | Transcervical transmandibular with double osteotomy | Horner’s syndrome | 11 | Alive NED |

| 9 | Transparotid-transcervical | No | 11 | Alive NED |

| 10 | Transcervical transmandibular with double osteotomy | No | 11 | Alive NED |

| 11 | Transcervical transmandibular with "swing" approach | Horner’s syndrome | 10 | Alive NED |

| 12 | Transcervical | No | 10 | Alive NED |

Results

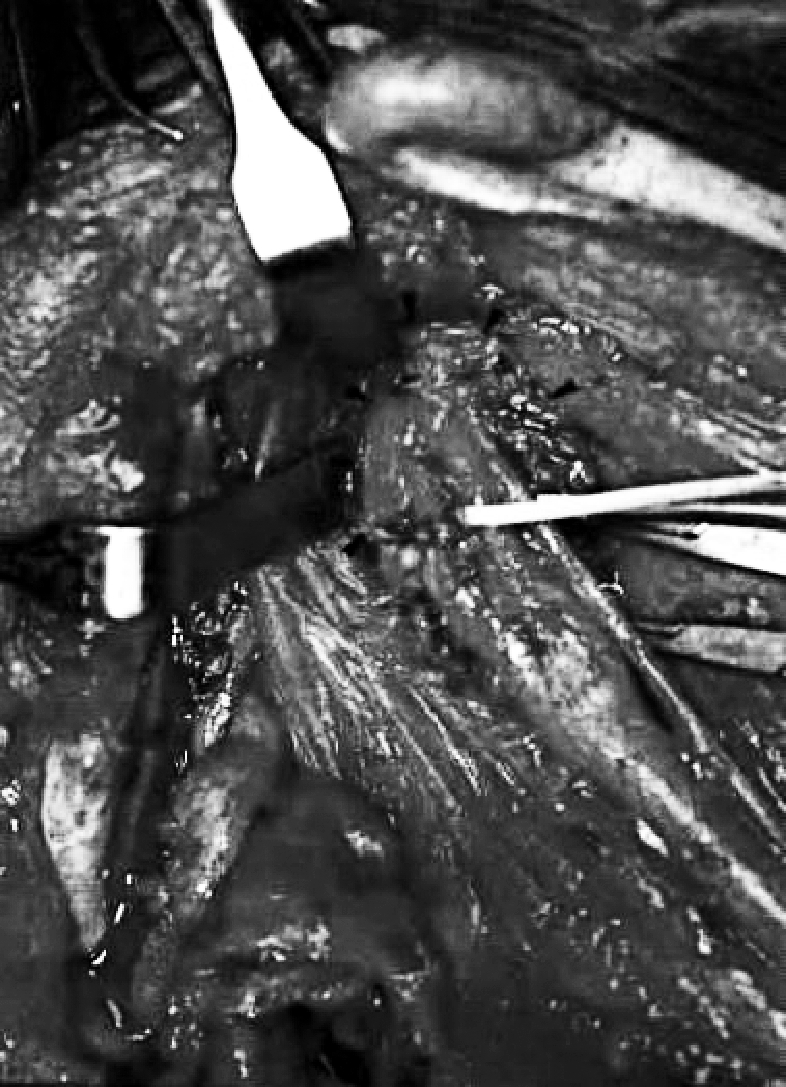

Of these PPS tumours, 8 were benign (66.6%) and 4 malignant (33.4%). The histological diagnosis was pleomorphic adenoma of the deep lobe of the parotid gland in 8 cases of which 2 were recurrent. The other 4 cases were: recurrent parotid adenocarcinoma (T3N1), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) metastasis from an occult primary tumour (TXN1) (Fig. 1), a tonsil region SCC (T2N0) extending into PPS and one late metastasis of a papillary thyroid carcinoma (T0N1) in a patient who had been submitted to thyroidectomy 30 years previously.

Fig. 1.

Patient n. 8. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) metastasis from occult primary tumour. A: Coronal MR showing tumour in parapharyngeal poststyloid space and its size. B: View of parapharyngeal poststyloid space occupied by metastasis that lies under internal carotid artery, after transcervical-transmandibular with double osteotomy approach.

In this study, 8/12 patients (66.6%) underwent FNAC (Table I) and the cytohistopathological comparison confirmed 7/8 (87.5%) of these diagnoses (one patient had a “non-diagnostic” result). The positive predictive value of the FNACs was 75% for benign tumours (3/4 were pleomorphic adenomas) and 100% for malignant tumours.

A transcervical-transmandibular approach was taken in 5 cases (41.6%): 3 underwent a double mandibular osteotomy without labial incision9 and the other 2 the “swing” mandibular technique 8. In 2 of these patients, histopathology revealed a deep parotid lobe pleomorphic adenoma (one was recurrent) and the other patient a SCC metastasis of an occult primary tumour. In the 2 cases treated with the “swing” mandibular technique, a recurrent parotid adenocarcinoma and a tonsil region SCC, extending into the PPS, were histologically diagnosed and required tracheotomy.

Four patients (33.4%) underwent transparotid-transcervical surgery for a pleomorphic adenoma (one was recurrent) of the deep lobe of the parotid gland in the prestyloid space, 4 cm in size.

In 2 patients (16.6%), a pleomorphic adenoma of the deep lobe of the parotid gland of 3 cm which caused a fullness in the tonsil region was removed with transoral surgery.

In the last case (8.4%), transcervical surgery was performed for a papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis. Post-operative complications occurred in 3/12 patients (25%). Two developed Horner’s syndrome due to sympathetic chain damage during resection. One patient had a temporary marginal mandibular of the facial nerve dysfunction, which healed spontaneously 6 months later.

Post-operative radiotherapy was carried out in 3/4 patients with malignancies. Disease status was evaluated in all patients in order to determine the best therapeutic approach. Eleven patients (91.6%) were still disease-free after a 10-year follow-up. The patient with a recurrent parotid gland adenocarcinoma (treated with surgery and radiotherapy) died of distant metastases 4 years after PPS surgery (Table II).

Discussion

PPS tumours usually present very few symptoms and are often associated with dysphagia, dyspnoea, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, cranial nerve deficits, Horner’s syndrome, pain, hoarseness, dysarthria and trismus. Sometimes, a neck mass is present but it is often discovered only during a routine physical examination. Intraorally, they commonly appear as a smooth submucosal mass displacing the lateral pharyngeal wall, tonsil and soft palate antero-medially and it is often misdiagnosed as an infection or a tonsil tumour. In addition, the space itself is clinically inaccessible since it is surrounded by the mastication muscles, the mandible, and parotid glands which makes physical examination of the tumour difficult. In these cases, a bimanual evaluation is the most effective clinical examination although tumours of < 2.5 cm are undetectable 12.

Imaging studies are used to predict the origin, side and the size of parapharyngeal tumours. MRI with gadolinium, is better than a CT scan and is the examination of choice. It can reliably distinguish a deep lobe parotid tumour from a primary parapharyngeal tumour of neurovascular origins or of extra-parotid minor salivary glands, from evidence, in T2 weighted slices, of the fatty layer between the tumour and the pharyngeal wall. In our patients, MRI (Fig. 1A) was performed in 8/12 cases and CT in the remaining 4. The lesion was detected in all cases. The mean tumour size was 4.6 cm (range 3–10 cm). Both CT and MRI were used only in one case to exclude mandibular infiltration in the event of recurrent parotid adenocarcinoma. Of these 12 PPS tumours, 9 were neoplasms in the prestyloid space. In actual fact, 8 tumours in this group originated from the parotid gland, whereas one of these 8 cases was a tonsil region SCC extending into the prestyloid space.

Angiography is recommended for all enhancing lesions or vascularised masses, particularly if imaging reveals a widening of the carotid bifurcation. This feature was not observed in any of the present cases.

US- or CT-guided FNAC is usually performed to determine the nature of the mass. According to data in the literature, FNAC is accurate in 90-95% of cases. It is performed transorally, transcervically or guided by CT or US and can predict the nature of the lesion which will assist surgeon-patient planning 13. In our study, 8/12 patients (66.6%) underwent FNAC (Table I) and the cyto-histopathological comparison confirmed 7/8 (87.5%) of these diagnoses (one patient had a “non-diagnostic” result). The positive predictive value of our FNACs was 75% for benign tumours (3/4 were pleomorphic adenomas) and 100% for malignant tumours and, therefore, proved to be a valid tool in our pre-surgery protocol.

An accurate diagnosis is essential for planning the best surgical approach to safely and radically remove PPS tumours.

Tumours which involve the PPS are primary neoplasms, metastatic cancer and lesions which overlap from neighbouring areas and are reported in the literature as 80% benign and 20% malignant 5. In our study, 66.6% were benign and 33.4% malignant.

A transcervical-transparotid approach, not only identifies and preserves the facial nerve, but also the external and internal carotid arteries, the internal jugular vein, the cranial nerves IX, X, XI, XII and the sympathetic nervous system chain. Most deep lobe tumours can be removed with this approach and it is particularly effective for small tumours. A superficial parotidectomy must be performed beforehand to identify and thus carefully preserve the facial nerve. A retractor will expose the PPS and create sufficient space to perform the digital dissection of deep lobe tumours by gently dividing the soft tissue and fibrous adhesions. However, extreme caution must be used during dissection, since rough handling may cause the tumour to rupture and spill into the surgical field, resulting in a high risk of local recurrence; furthermore absolute haemostasis must be secured prior to closure. This approach cannot be used when the mass is > 4 cm, where tumour adhesion is dense or in patients who have previously undergone attempts to biopsy or remove it or when an infiltrating malignancy is suspected.

In our study, this approach was used in the removal of 3 primary and one recurrent pleomorphic adenomas. The mean tumour size was 4 cm; facial nerve function was preserved in all cases and no other complications occurred.

The transcervical approach was used on a papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis. This approach is usually used for lesions of < 4 cm, not originating in the parotid gland, and with limited cranial extension.

A transoral approach was adopted in 2 patients with a small pleomorphic adenoma of the deep lobe of parotid, which medially displaced the tonsillar region. This approach, however, can only be used for benign prestyloid space tumours of < 3 cm. However, the transoral approach is considered to be unsafe since it is correlated with many post-operative complications such as haemorrhage, fistulas, dehiscence and nerve damage and, for these same reasons, the combined transoral-transcervical approach should also be avoided 5.

Anatomically, the mandible represents a significant obstacle to successful PPS surgery and many solutions have been suggested to overcome this problem. These can be divided into two distinct groups: a) retraction of the mandible in a protruded position, or b) different mandibulotomy techniques 5 7–9. A midline mandibulotomy or a parasymphysis osteotomy, anterior to the mental nerve, with a labiotomy and an intraoral incision along the floor of the mouth, could be combined with a transcervical or transcervical-transparotid approach, since it would enlarge PPS exposure. However, this procedure would also require a tracheotomy and a nasogastric feeding tube.

In the mandibular “swing” approach, the mandible is retracted laterally to expose the PPS as much as possible, and to preserve the mental nerve 8. The disadvantages of this approach are cutting of the lower lip and the subdislocation of the temporal-mandibular articulation. The “swing” approach must be used for malignant or invasive tumours with mucosal involvement of the pharyngeal wall or invasion of the skull base or the pterygomaxillary fossa. This approach was used in 2 of our malignant cases, namely, the recurrent adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland and the SCC of the tonsillar region with extensive PPS involvement.

The transcervical-transmandibular approach with double osteotomy of the parasymphysis and the condyle of the mandible 9 was used in 3 cases. This combination, again, improves exposure of the PPS while avoiding morbidity associated with labiotomy, midline mandibulotomy and the intraoral incision. Moreover, application of a rigid mini-plate fixation, for osteosynthesis with respect to dental occlusion allowed us to avoid an intermaxillary block. This approach provides good control of tumour extension towards the skull base, the pterygomaxillary fossa and the large neck vessels (Fig. 1B). At the same time, it also avoids labiotomy and dysfunction-like anaesthesia of the hemi-mental and low hemi-labial region, caused by the severing of the mental nerve.

In our experience, 4 cm is the limit for radical tumour excision with the transcervical approach without mandibulotomy. For a safe and radical resection of tumours > 4 cm the “swing” approach or the transmandibular with a double osteotomy is required.

In all these different approaches used in our cases, postoperative complications were very low. One patient had a temporary marginal mandibular of the facial nerve dysfunction for 6 months with a spontaneous resolution, while Horner’s syndrome was described in 2/12 cases.

We recommend post-operative radiotherapy for patients with high-grade malignancies or where wide surgical margins cannot be achieved, as suggested in the literature 6 7.

The 12 patients in the present study were followed-up for at least 10 years, since late recurrences of parotid tumours can occur even after 10 years 14–16. Each patient underwent a follow-up protocol of clinical controls and US every 6 months, CT and/or MRI once a year.

Our systematic clinical-therapeutic protocol to the diagnosis and the surgical procedures are in agreement with other studies reported in the literature 1 17, where PPS tumours have been treated with the use of one of the various surgical approaches described in relation to the histopathological diagnosis (benign or malignant), to the side (prestyloid or poststyloid) and to the size (±4 cm) of the neoplasia and, moreover, with a long-term follow-up.

Therefore, the results of our experience, in the treatment of the tumours of the PPS, confirm the need to follow a careful preoperative diagnostic procedure that must take advantage of imaging studies (CT, MRI) and of cytology (FNAC), in order to plan surgical treatment with a safe approach and that reduces complications, aesthetic-functional damage as well as risk of recurrence.

References

- 1.Khafif A, Segev Y, Kaplan DM, Gil Z, Fliss DM. Surgical management of parapharyngeal space tumors: a 10-year review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;132:401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attia A, El-Shafiey M, El-Shazly S, Shouman T, Zaky I. Management of parapharyngeal space tumors at the National Cancer Institute, Egypt. J Egypt Natl Canc Ins 2004;16:34-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lombardi D, Nicolai P, Antonelli AR, Maroldi R, Farina D, Shaha AR. Parapharyngeal lymph node metastasis: an unusual presentation of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck 2004;26:190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ducci M, Bozza F, Pezzuto RW, Palma L. Papillary thyroid carcinoma metastatic to the parapharyngeal space. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2001;20:439-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen KD. Tumors and surgery of the parapharyngeal space. Laryngoscope 1994;104:1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carew JF, Spiro RH, Singh B, Shah JP. Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;5:539-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonetti JP, Marzo SJ, Petruzzelli GJ, Herr B. Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;133:319-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiro RH, Gerold FP, Strong EW. Mandibular “swing” approach for oral and oropharyngeal tumors. Head Neck Surg 1981;3:371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seward GR. Tumors of the parapharyngeal space. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1989;34:111-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teng MS, Gender EM, Buchbinder D, Urken ML. Subcutaneous mandibulotomy: a new surgical access for large tumors of the parapharyngeal space. Laryngoscope 2003;113:1893-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad F, Waqar-uddin, Khan MY, Khawar A, Bangush W, Aslam J. Management of parapharyngeal space tumours. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2006;16:7-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrau RL, Myers EN, Johnson JT. Management of tumors arising in the parapharyngeal space. Laryngoscope 1990;100:583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrag TY, Lin FR, Koch WM, Califano JA, Cummings CW, Farinola MA, et al. The role of pre-operative CT-guided FNAB for parapharyngeal space tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;136:411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahab R, Heliwell T, Jones AS. How we do it: a series of 114 primary pharyngeal space neoplasms. Clin Otolaryngol 2005;30:364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malone JP, Agrawal A, Schuller DE. Safety and efficacy of transcervical resection of parapharyngeal space neoplasm. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2001;110:1093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luna-Ortiz K, Navarrette-Aleman JE, Granados-Garcìa M, Herrera-Gòmez A. Primary parapharyngeal space tumors in a Mexican cancer center. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;132:587-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SM, Burkey BB, Netterville JL. Surgical management of parapharyngeal space masses. Head Neck 2005;27:669-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]