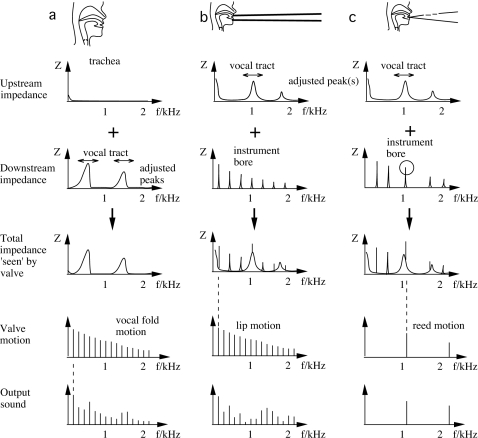

Figure 2. Schematic figures show idealizations of the duct-valve interactions in the voice (a), a lip valve instrument (b), and a reed instrument (c).

The upstream and downstream impedances add to give the total impedance Z. (a) Illustrates the source-filter theory: the vocal fold motion is assumed independent of Z, but tract resonances transmit certain harmonics more efficiently into the sound field at the open mouth. The vocal tract impedance spectrum has a different form when seen from the glottis (a) and from the lips (b) and (c). In (b) and (c) the mouth is closed so it will be difficult to change low frequency impedance peaks significantly by altering the mouth geometry. An impedance peak may be changed over a range near 1 kHz, which alters the total impedance (instrument+tract) over the same range. The timbre effect, as used by didjeridu players, is shown in (b) where vocal tract impedance peaks inhibit output sound. For a high pitched instrument, such as a saxophone played in the altissimo range (c), a vocal tract resonance may help determine the playing range by selecting which of the sharp peaks in the impedance spectrum of the instrument bore will determine the playing regime.