Abstract

An uncontrolled trial reported that sodium thiosulfate reduces formation of calcium kidney stones in humans, but this has not been established in a controlled human study or animal model. Using the genetic hypercalciuric rat, an animal model of calcium phosphate stone formation, we studied the effect of sodium thiosulfate on urine chemistries and stone formation. We fed genetic hypercalciuric rats normal food with or without sodium thiosulfate for 18 wk and measured urine chemistries, supersaturation, and the upper limit of metastability of urine. Eleven of 12 untreated rats formed stones compared with only three of 12 thiosulfate-treated rats (P < 0.002). Urine calcium and phosphorus were higher and urine citrate and volume were lower in the thiosulfate-treated rats, changes that would increase calcium phosphate supersaturation. Thiosulfate treatment lowered urine pH, which would lower calcium phosphate supersaturation. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in calcium phosphate supersaturation or upper limit of metastability between thiosulfate-treated and control rats. In vitro, thiosulfate only minimally affected ionized calcium, suggesting a mechanism of action other than calcium chelation. In summary, sodium thiosulfate reduces calcium phosphate stone formation in the genetic hypercalciuric rat. Controlled trials testing the efficacy and safety of sodium thiosulfate for recurrent kidney stones in humans are needed.

Nephrolithiasis is one of the most common disorders of the urinary tract, affecting approximately 12% of men and 6% of women during their lifetimes in industrialized countries.1 Approximately 80% of kidney stones are composed primarily of calcium salts. Despite the high prevalence of kidney stone disease, there has been little progress in developing new therapies to prevent stone formation, especially in patients who have formed a kidney stone and who are at significantly increased risk for forming additional stones. The lack of progress in identifying new therapies for nephrolithiasis has been disappointing to the many patients who experience recurrent stone formation.

Sodium thiosulfate (STS), Na2S2O3, is a compound with a long history of medicinal use.2,3 Currently, it is used for treatment of cyanide toxicity and as a neutralizing agent to reduce the toxicity of cisplatin chemotherapy.4–6 The effectiveness of STS in these diseases lies in its antioxidant activity and the availability of a sulfur group for donation. In 1985, Yatzidis7 reported on using STS as treatment for recurrent calcium nephrolithiasis. In a 4-yr study of 34 patients, he reported an 80% reduction in stone rates, compared with the patients’ own pretreatment stone formation rate. Unfortunately, no follow-up, prospective, controlled trials have been performed to determine the effectiveness of STS in preventing recurrent stone formation; however, anecdotal reports of successful treatment of calciphylaxis with STS in patients with end-stage kidney disease have stimulated interest in this compound as a potential therapy for disorders of calcium deposition, including stone disease.8–16 The mechanism by which STS affects calcium deposition is not known.

Before pursuing new studies in humans, we chose first to study this drug in the genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming (GHS) rats because 40 to 50% of humans with kidney stones will have hypercalciuria, making it the most common metabolic abnormality. The GHS rat colony has been bred for hypercalciuria and now excretes approximately 8 to 10 times more urine calcium than similarly fed control rats.17 The pathophysiology of the hypercalciuria seems similar to that in humans in that it involves intestinal hyperabsorption,18,19 reduced renal tubular reabsorption,20 and increased bone mineral lability.21,22 Virtually all of the GHS rats form kidney stones, whereas control rats have no evidence of stone formation.23 On a standard rat diet, the kidney stones formed contain only calcium and phosphate.24 Here we report the results of a controlled trial to determine whether STS reduces stone formation in an animal model of spontaneous calcium phosphate stone formation.

RESULTS

Urine Chemistries

Our goal was to obtain a urine thiosulfate concentration of approximately 4 mmol/L, similar to that attained in the patients treated by Yatzidis.7 Average urine thiosulfate concentrations in the STS-treated rats at weeks 6, 12, and 18, respectively, were 4.15 ± 0.32, 3.51 ± 0.30, and 3.91 ± 0.34 mmol/L (mean ± SEM). Thiosulfate excretion was 0.14 ± 0.01, 0.11 ± 0.01, and 0.12 ± 0.01 mmol/d for weeks 6, 12, and 18, respectively. Rats in the control group, which had no added thiosulfate, had urine concentrations of thiosulfate below the level of detection of the assay.

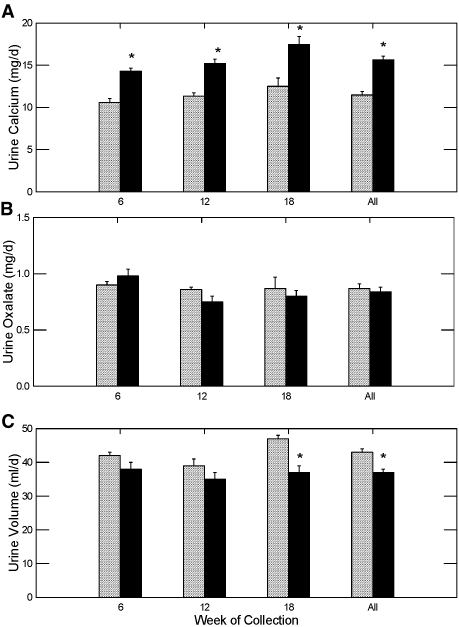

Urine calcium was significantly higher in the STS group compared with the control group during all three urine collections, whereas there was no change in urine oxalate (Figure 1, A and B, respectively). Urine volume was lower in the STS treated rats compared with the control group during the last collection period and when all urine volume measurements were combined (Figure 1C). No change in stool consistency was noted during the study to explain the difference in urine volume, but a formal quantification of stool volume was not performed.

Figure 1.

Urine calcium and oxalate excretion and urine volume (mean ± SEM) in GHS rats fed a standard diet with (▪) or without STS (  ) added. *Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.001.

) added. *Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.001.

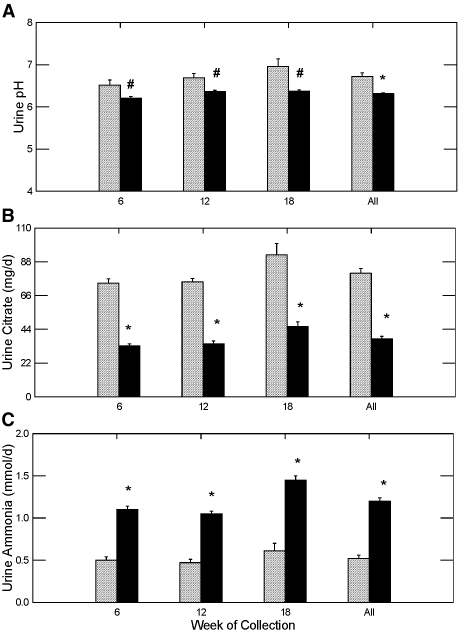

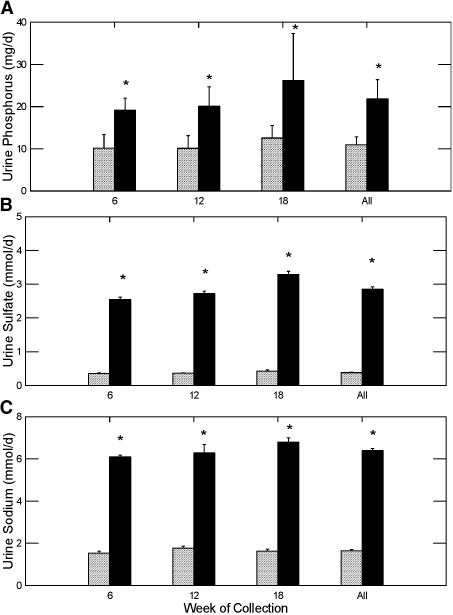

Urine pH was significantly lower in GHS rats treated with STS compared with the control group, whereas urine citrate was significantly lower than the control in all three urine collections (Figure 2, A and B, respectively). This was accompanied by an increase in ammonium excretion (Figure 2C) and phosphorus excretion (Figure 3A), which strongly suggests that net acid production was significantly higher in the rats being treated with STS; however, urinary bicarbonate, needed to calculate formally net acid excretion, was not measured. Sulfate excretion was markedly elevated in the STS-treated rats, suggesting considerable metabolism of thiosulfate to sulfate (Figure 3B), likely the source of the acid load in the STS-treated rats. Urine sodium was elevated in the rats treated with STS as a result of the sodium in this compound (Figure 3C). Both the acid and sodium loads likely contributed to the increase in urine calcium (Figure 1A).

Figure 2.

Urine pH and urine citrate and ammonia excretion in GHS rats fed a standard diet with (▪) or without STS (  ) added. *Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.001; #different from control in the same time period, P < 0.05.

) added. *Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.001; #different from control in the same time period, P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Urine phosphorus, sulfate, and sodium excretion in GHS rats fed a standard diet with (▪) or without STS (  ) added. *Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.001.

) added. *Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.001.

Urine Supersaturation and Upper Limit of Metastability

We performed a direct measurement of supersaturation (SS), instead of calculating a value, because the iterative computer program Equil 2 commonly used to estimate urine saturation does not include thiosulfate as an ionic species.25 Results from the last collection period are not reported for SS and upper limit of metastability (ULM) because spontaneous crystallization of calcium salts occurred in many of the thymol-preserved urine samples during transport for unknown reasons. The crystallization occurred in urine from both control and STS-treated rats.

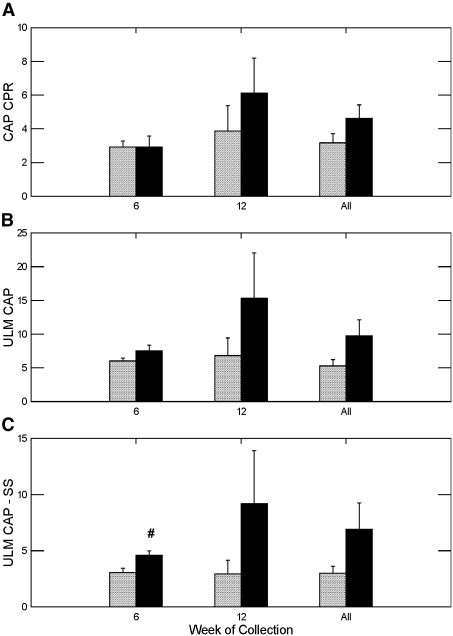

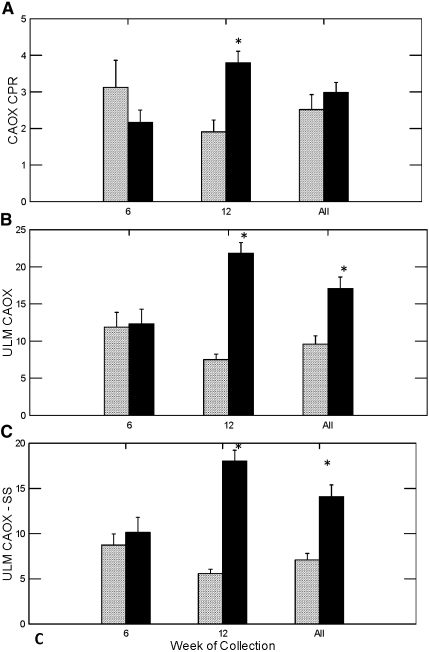

Calcium phosphate (CaP) SS, as determined by the concentration product ratio (CPR), did not differ in week 6 but was numerically higher among the STS groups in week 12 and all weeks combined than among the control group for the same periods; however, the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 4A). Calcium oxalate (CaOx) CPR did not differ in week 6 but was significantly higher in the STS-treated rats in week 12. The combined data did not show any significant difference in CaOx CPR (Figure 5A).

Figure 4.

Urine CaP concentration product ratio, ULM and the difference of ULM and SS. #Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Urine CaOx CPR, ULM, and the difference of ULM and SS. *Different from control in the same time period, P < 0.001.

The ULM is a measure of the ability of urine to resist crystallization, such that an increase in ULM can offset an elevated SS and prevent stone formation. Rats treated with STS showed a trend toward higher CaP CPR at the end point of the ULM experiment than did control rats in weeks 6, 12, and all weeks combined (Figure 4B), although the difference did not reach statistical significance. To judge the net effect of STS on crystallization, we calculated the difference between the urine CaP ULM and SS. The greater the difference between the ULM and SS, the lower the risk for crystallization. The difference between CaP ULM and SS was significantly higher in the STS-treated rats in week 6 but was not different in week 12 or both weeks combined (Figure 4C). For CaOx, the ULM did not differ in week 6 but was significantly higher in the STS-treated rats in week 12 and all weeks combined (Figure 5B). The difference between CaOx ULM and SS was significantly higher in week 12 and all weeks combined.

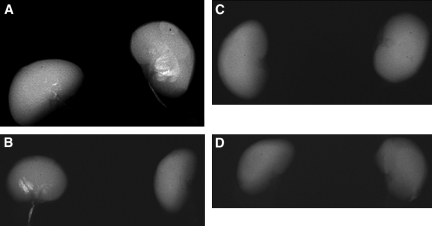

Stone Formation

Radiologic examination of kidneys dissected from the GHS rats revealed 11 of 12 rats in the control group and only three of 12 rats in the STS group (P < 0.002) formed kidney stones. (Figures 5 and 6, left). When each kidney was assessed separately, 15 of 24 kidneys in the control group and three of 24 kidneys in the STS group developed kidney stones (P < 0.001; Figure 6, right). In addition, the number and size of the stones were much less in the STS-treated rats than in the control group. There were no significant differences in urine chemistries between the STS-treated rats that formed stones and those that did not form stones.

Figure 6.

(A through D) Representative x-rays of the kidneys from four rats, two (A and B) in the control group with no STS therapy and two (C and D) that were treated with STS. Three of the four kidneys in the control group contain kidney stones; no stones are seen in the rats treated with STS.

Effect of Anions on Ionized Calcium

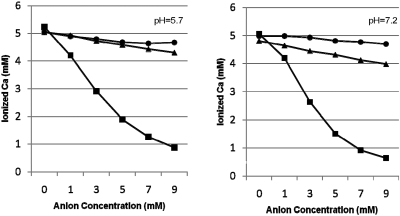

Ionized calcium decreased modestly as the concentration of sulfate and thiosulfate increased up to 9 mM at both pH 5.7 and 7.2 (Figure 7). Sulfate lowered ionized calcium slightly more than did thiosulfate at both pH levels. In contrast, citrate, which is known to be an effective calcium-complexing agent, was significantly more effective in lowering ionized calcium than either sulfate or thiosulfate.

Figure 7.

Effect of anions on ionized calcium. Citrate (▪) at increasing concentration lowers ionized calcium to a much greater extent than either sulfate (▴) or thiosulfate (•) in acetate buffer at pH 5.7 (left) or HEPES buffer at pH 7.2 (right).

DISCUSSION

We chose to investigate the efficacy of STS to prevent stone formation in the GHS rat for a number of reasons. First, the dietary and environmental factors of these rats housed in metabolic cages for the entire study can be completely controlled. Second, the rats form stones over the course of months, which allowed us to use stone formation as a primary end point; prospective, controlled pharmacologic trials to prevent stones in humans generally require 3 yr of follow-up.26–30 Third, the GHS rats are a model of spontaneous CaP stone formation. Because there has been considerable focus on the role of CaP plaque as the initial nidus of stone formation in humans31 and the apparent efficacy of STS in treating calciphylaxis,8–16 which is also a CaP mineralization disease, we believed an animal model of CaP stone disease would provide significant insights into the effect of STS on cap crystallization. We found that STS significantly reduced kidney stone formation in the GHS rats.

The initial report of STS in the treatment of calcium kidney stones was by Yatzidis in 1985.7 Thirty-four patients with recurrent calcium nephrolithiasis were treated with STS at a dosage of 10 mmol orally twice per day for an average of 4 yr. The number of CaOx versus CaP stone formers in the study was not reported. The author reported a reduction in stone rate from 0.98 to 0.11 stones per patient per year with the drug compared with the pretreatment control period. The patients were not chosen on the basis of any metabolic subtype, but, as expected, 18 of the 34 patients had hypercalciuria. No changes in serum or urine calcium, phosphorus, or magnesium were noted during treatment with STS compared with baseline. Urinary thiosulfate excretion averaged 4.2 mmol/d during therapy; thus, 21% of the oral dose was excreted via the kidney. Unfortunately, urine oxalate, citrate, uric acid, and pH were not reported, so a complete assessment of urine risk factors was not possible. The only other report of STS therapy in kidney stone disease was a case report in 1994 of a patient with renal tubular acidosis and nephrocalcinosis, which improved with oral STS therapy.32 No other studies either supporting or refuting the effectiveness of this therapy in kidney stone disease have been published.

The mechanism by which thiosulfate reduces pathologic crystallization is not known. Yatzidis suggested that thiosulfate complexed calcium, because calcium thiosulfate is much more soluble than either CaOx or calcium phosphate; however, the solubility of a salt does not indicate the ability of a one molecule to complex another. Our measurements of the effect of thiosulfate on ionized calcium suggest that thiosulfate is not a significant calcium-complexing agent (Figure 7). At dosages achieved in urine, the effect is minimal and easily dwarfed by that of citrate at 1 to 3 mM, concentrations typically found in human urine.33 The urine data presented in this article also do not support a significant role for thiosulfate complexation of calcium. The increased urine calcium and phosphate and decreased urine citrate excretion are offset by a decrease in urine pH, making it hard to predict the effect of thiosulfate on urine saturation. If STS prevented stones by complexing calcium, then we would have expected a lower CaP CPR value in the treated animals, which we did not find. The CaP ULM was slightly higher in the STS-treated rats, and the CaP ULM to SS difference was significantly higher in week 6 and but not in week 12 in the STS-treated rats. Interestingly, there was a significant increase in the CaOx ULM and the ULM to SS difference, suggesting an inhibition of CaOx crystallization; however, the GHS rats were fed in a manner that would cause CaP stones to form. Whether STS therapy will increase CaOx ULM and prevent CaOx stone formation in the setting of hyperoxaluria will need to be tested in a separate experiment. In total, these findings may indicate some direct inhibitory effect on crystallization by thiosulfate, the elevated urine sulfate, or some other metabolic effect of thiosulfate. Perhaps proteins released from acid-induced bone dissolution affected CaP crystallization. Thiosulfate is also a powerful reducing agent, which provides another potential mechanism, although not specifically tested here. Whatever the mechanism of action, STS clearly reduced stone formation in this well-controlled experimental model.

Although the rat model showed significant reduction in stone rates, we do need to recognize potential differences between rats and humans in interpreting results. A much higher dosage of STS was required to obtain the desired level of urine thiosulfate because only 6% of the thiosulfate administered to the rats was excreted in the urine as compared with 21% for humans. The higher dosage led to a significant sodium and acid load with the predictable outcome of worsening the urine calcium excretion in the rats. Yatzidis in his study reported that urine calcium was stable throughout the experiment, but the sodium load was much lower adjusting for the size difference between humans and the GHS rats.7 Yatzidis did not report urine pH, citrate, or ammonium, so we cannot tell whether an acidosis was induced in the humans. Two case studies of STS in calciphylaxis reported patients’ developing a mild metabolic acidosis during therapy10,15; other case reports make no mention of acid-base abnormalities. It is unlikely that the acidosis was responsible for preventing stone formation by lowering urine pH, because a previous study34 of the effect of acid loading in GHS rats did not show a reduction in CaP stone formation despite consistently lowering urine pH below 5.6, significantly lower than the urine pH attained in this study.

STS has a long history of medicinal use in disorders other than nephrolithiasis.2,3 Currently, the major clinical uses of STS are for treatment of cyanide toxicity and to reduce the toxicity of cisplatin chemotherapy.4–6 There has been a surge of interest in the use of STS to treat calciphylaxis in patients with end-stage kidney disease. There are multiple case reports showing improvement in pain, healing of skin ulcers, and radiographic evidence of resolution of metastatic calcification.8–16 In these reports, STS was given intravenously, orally, and even intraperitoneally. There has also been a case report of successful treatment of gadolinium-induced nephrogenic systemic fibrosis using STS.35

The Food and Drug Administration recognizes STS as a GRAS compound (generally recognized as safe). In all human studies of STS, only minimal adverse effects have been reported. For treatment of cyanide toxicity in adults, 12.5 g (79 mmol) of STS is infused without adverse effect; in fact, up to 25 g has been infused without toxicity in humans.4 In studies of long-term use in end-stage kidney disease, no significant adverse events have been reported. When used orally in the kidney stone population, Yatzidis reported the only adverse effect to be foul-smelling stools but noted no patient stopped the medication as a result of adverse effects.7 One potential concern is the acid load we found during STS treatment in the GHS rats. If humans also have a significant increase in acid production with STS therapy, then there is a risk for bone demineralization during long-term therapy. This is particularly worrisome in hypercalciuric stone formers, who have an increased risk for fracture and reduced bone mineral density. In addition, patients with CaP stones and distal renal tubular acidosis may be particularly unsuited for STS therapy, because they would not be able to excrete the acid load and could develop a significant metabolic acidosis.

Overall, our results support the hypothesis that STS is an effective therapy to prevent CaP kidney stones. That STS seems to be safe and well tolerated makes this an interesting therapeutic alternative. The mechanism of action may involve an increase in the cap ULM to SS difference, but it seems to be other than that of simple calcium complexation. Typical urine risk factors would not be adequate to assess the efficacy of STS therapy, so other markers would need to be identified to guide treatment if it is to be used in humans. Further studies in humans are needed to define the metabolic effects and safety of long-term STS ingestion and to test the hypothesis that STS would reduce stone formation.

CONCISE METHODS

All rats were housed in metabolic cages at University of Rochester Vivarium, according to federal standards (OLAW Assurance No. A1807-01 and University of Rochester PHS Assurance No. A-3292-01). Rats were seen frequently by veterinary staff of this Association for Assessment of Laboratory Animal Care-approved facility.

Twenty-four GHS rats, approximately 190 g each, were equally divided into two groups; both groups were fed 13 g of standard rat chow (1.2% calcium, 0.65% phosphate) for the first 12 wk and 15 g for the last 6 wk (dietary needs increase as a result of growth) and kept in metabolic cages for the duration of the study. The STS treatment group had 500 mg/d STS pentahydrate added to their chow, which was increased to 580 mg/d STS after week 12. At 6, 12, and 18 wk, four consecutive 24-h urine samples were collected. Two collections (first and third) were in 0.5-ml concentrated HCl for the measurements of calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, ammonia, creatinine, potassium, sodium, oxalate, and citrate. Two collections (second and fourth) were in the presence of thymol for the measurements of pH, sulfate, thiosulfate, and the ULM and SS experiments (run on urine samples from day 2 only). The data from days 1 and 2 and days 3 and 4, respectively, were combined to provide two complete sets of 24-h calculations.

All urine samples were collected by technicians at University of Rochester and sent to Litholink via overnight Federal Express after days 2 and 4 of each set of urine collections. After the 18th week, each rat was killed; the kidneys, ureters, and bladder were dissected en block; and x-rays of the urinary system were performed. Calcifications were counted in each kidney by D.A.B., who was blinded to the treatment status of the rats.

Urine Chemistries

Calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, ammonia, and creatinine were measured spectrophotometrically using the Beckman CX5 Pro autoanalyzer (Beckman Instruments, Brea, CA). Potassium and sodium were measured by ion-specific electrodes on the Beckman CX5. Urine pH was measured using a glass electrode.

Thiosulfate, oxalate, citrate, and sulfate were measured by ion chromatography using a Dionex ICS 2000 system (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Samples were loaded into a 25-μl loop using an autosampler and injected onto an AG-11 guard column and AS-11 analytical column in series, with KOH as the mobile phase. Ion peaks were detected using a conductivity meter with the eluent background conductivity suppressed using an anion self-regenerating suppressor. Sulfate and thiosulfate were measured in the unacidified urine specimens because thiosulfate is stable in urine at ambient pH but decays in acidified urine samples.

Urine SS

Urine specimens had gentamicin (0.02 mg/ml) added to prevent bacterial growth. Thirty milligrams of brushite (CaP) or CaOx crystals, for determination of CaP and CaOx saturation, respectively, was added to a 5-ml aliquot of urine, which had been warmed to 37°C. Specimens were continuously stirred, and the pH of each sample was measured at 24 and 48 h and maintained at the original pH by addition of either HCl or KOH as needed; the change in volume from added acid or base was <1%. The urine samples were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min; the supernatant was collected and spun through a 0.2-μm filter tube at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. One milliliter of filtrate was acidified with 50 μl of 4 N HCl, and the final calcium and phosphorus concentrations were measured for CaP saturation or calcium and oxalate concentration measured for CaOx saturation.

The CaP CPR was calculated as the molar product of [calcium × phosphorus] at the baseline divided by the [calcium × phosphorus] at the end of incubation.36,37 The CaOx CPR was determined in the same manner except oxalate replaces phosphorus in the calculation. A value of 1 is the saturation point of the urine, whereas >1 indicates that the urine is supersaturated and <1 that the urine is undersaturated.

Upper Limit of Metastability

The ULM defines the level of SS required for crystallization of a salt. It is quantified by increasing the calcium concentration (for CaP ULM) or oxalate concentration (for CaOx ULM) of a urine sample until precipitation occurs, identified as an increase in turbidity of the urine sample. Urine samples collected in thymol were used for the ULM measurements, and gentamicin was added to 5-ml aliquots of each urine sample (final concentration of 0.02 mg/ml) to prevent bacterial growth during the experiment. The pH was then adjusted to 6.4 for cap ULM measurement, which ensures crystallization of cap when calcium is added to the urine. For CaOx ULM, the urine samples were adjusted to pH 5.7. Urine samples were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min and warmed for 30 min at 37°C in an incubator. Two milliliters of the urine sample was placed in a cuvette of a Beckman DU 650 Spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments). The analytical absorbance was set to 620 nm, and the background was set to 250 nm. The spectrophotometer is equipped with a water bath set at 37°C and cuvette stirring capabilities. Every 3 min, 5 μl of CaCl2 for CaP ULM or sodium oxalate for CaOx ULM was added to the cuvette. When the OD reading increased 0.1 U from the baseline, crystallization had occurred and the final ligand concentration, either calcium or oxalate, required to induce crystallization was calculated.

Effect of Anions on Ionized Calcium

To determine the effect of STS on ionized calcium levels, we compared equimolar concentrations of STS, sodium sulfate, and sodium citrate. Ionized calcium was measured using a calcium electrode (Thermo Electron Corp., Beverly, MA) in combination with a silver/silver chloride reference electrode. The electrode was calibrated using CaCl2 standards of 1 and 10 mM in 150 mM of NaCl to maintain constant ionic strength. The study was performed at pH 5.7 in 5 mM of sodium acetate and 150 mM of NaCl buffer and at pH 7.2 in 5 mM of HEPES and 150 mM NaCl buffer. The electrode was calibrated in the same buffer used in the solutions to be tested. Each anion was studied at concentrations varying from 1 to 9 mM. All ionized calcium measurements were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SYSTAT 12 Software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Comparison between control and STS groups was done using t tests with Bonferroni correction used for multiple comparisons. Kidney stone formation rates were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

DISCLOSURES

J.R.A. is an employee of Litholink Corp. and consultant for Oxthera Corp. and Altus Pharmaceuticals; S.E.D. and C.L. are employees of Litholink Corp.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants R43 DK075194 (J.R.A.), RO1 AR 46289 (D.A.B.), and RO1 DK 75462 (D.A.B.) from the National Institutes of Health.

This work was presented in abstract form at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology; November 2, 2007.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, Nyberg LM, Curhan GC: Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976–1994. Kidney Int 63: 1817–1823, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litwins J, Boyd LJ, Greenwald L: The action of sodium thiosulfate on the blood. Exp Med Surg 1: 252–258, 1943 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theis FV, Freeland MR: Thromboangiitis obliterans. Surgery 11: 101–117, 1942 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskin SI, Horowitz AM, Nealley EW: The antidotal action of sodium nitrite and sodium thiosulfate against cyanide poisoning. J Clin Pharmacol 32: 368–375, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howell SB, Pfeifle CL, Wung WE, Olshen RA, Lucas WE, Yon JL, Green M: Intraperitoneal cisplatin with systemic thiosulfate protection. Ann Intern Med 97: 845–851, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfeifle CE, Howell SB, Felthouse RD, Woliver TB, Andrews PA, Markman M, Murphy MP: High-dose cisplatin with sodium thiosulfate protection. J Clin Oncol 3: 237–244, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yatzidis H: Successful sodium thiosulphate treatment for recurrent calcium urolithiasis. Clin Nephrol 23: 63–67, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araya CE, Fennell RS, Neiberger RE, Dharnidharka VR: Sodium thiosulfate treatment for calcific uremic arteriolopathy in children and young adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1161–1166, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mataic D, Bastani B: Intraperitoneal sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Ren Fail 28: 361–363, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brucculeri M, Cheigh J, Bauer G, Serur D: Long-term intravenous sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of a patient with calciphylaxis. Semin Dial 18: 431–434, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yatzidis H, Agroyannis B: Sodium thiosulfate treatment of soft-tissue calcifications in patients with end stage renal disease. Perit Dial Bull 7: 250–252, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerra G, Shah RC, Ross EA: Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: Case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 1260–1262, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadakis JT, Patrikarea A, Digenis GE, Stamatelou K, Ntaountaki I, Athanasopoulos V, Tamvakis N: Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of tumoral calcifications in a hemodialysis patient without hyperparathyroidism. Nephron 72: 308–312, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landau D, Krymko H, Shalev H, Agronovich S: Transient severe metastatic calcification in acute renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 22: 607–611, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA: Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 1104–1108, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meissner M, Bauer R, Beier C, Betz C, Wolter M, Kaufmann R, Gille J: Sodium thiosulphate as a promising therapeutic option to treat calciphylaxis. Dermatology 212: 373–376, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bushinsky DA, Frick KK, Nehrke K: Genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 403–418, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XQ, Tembe V, Horwitz GM, Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ: Increased intestinal vitamin D receptor in genetic hypercalciuric rats: A cause of intestinal calcium hyperabsorption. J Clin Invest 91: 661–667, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bushinsky DA, Favus MJ: Mechanism of hypercalciuria in genetic hypercalciuric rats: Inherited defect in intestinal calcium transport. J Clin Invest 82: 1585–1591, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuruoka S, Bushinsky DA, Schwartz GJ: Defective renal calcium reabsorption in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 51: 1540–1547, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bushinsky D, Neumann K, Asplin JR, Krieger N: Alendronate decreases urine calcium and supersaturation in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 55: 234–243, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krieger NS, Stathopoulos VM, Bushinsky DA: Increased sensitivity to 1,25(OH)2D3 in bone from genetic hypercalciuric rats. Am J Physiol 271: C130–C135, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bushinsky DA, Grynpas MD, Nilsson EL, Nakagawa Y, Coe FL: Stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric rats. Kidney Int 48: 1705–1713, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bushinsky DA, Parker WR, Asplin JR: Calcium phosphate supersaturation regulates stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. Kidney Int 57: 550–560, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Werness PG, Brown CM, Smith LH, Finlayson B: EQUIL 2: A basic computer program for the calculation of urinary saturation. J Urol 134: 1242–1244, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ettinger B, Pak CY, Citron JT, Thomas C, Adams-Huet B, Vangessel A: Potassium-magnesium citrate is an effective prophylaxis against recurrent calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J Urol 158: 2069–2073, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ettinger B, Citron JT, Livermore B, Dolman LI: Chlorthalidone reduces calcium oxalate calculous recurrence but magnesium hydroxide does not. J Urol 139: 679–684, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laerum E, Larsen S: Thiazide prophylaxis of urolithiasis: A double- blind study in general practice. Acta Med Scand 215: 383–389, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barcelo P, Wuhl O, Servitge E, Roussaud A, Pak C: Randomized double-blind study of potassium citrate in idiopathic hypocitraturic calcium nephrolithiasis. J Urol 150: 1761–1764, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borghi L, Meschi T, Guerra A, Novarini A: Randomized prospective study of a nonthiazide diuretic, indapamide, in preventing calcium stone recurrences. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 22[Suppl 6]: S78–S86, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, Parks JH, Bledsoe SB, Shao Y, Sommer AJ, Paterson RF, Kuo RL, Grynpas M: Randall's plaque of patients with nephrolithiasis begins in basement membranes of thin loops of Henle. J Clin Invest 111: 607–616, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agroyannis BJ, Koutsikos DK, Tzanatos HA, Konstadinidou IK: Sodium thiosulphate in the treatment of renal tubular acidosis I with nephrocalcinosis. Scand J Urol Nephrol 28: 107–108, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curhan GC, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ: Twenty-four-hour urine chemistries and the risk of kidney stones among women and men. Kidney Int 59: 2290–2298, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bushinsky DA, Grynpas MD, Asplin JR: Effect of acidosis on urine supersaturation and stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric stone forming rats. Kidney Int 59: 1415–1423, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yerram P, Saab G, Karuparthi PR, Hayden MR, Khanna R: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: A mysterious disease in patients with renal failure—Role of gadolinium-based contrast media in causation and the beneficial effect of intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 258–263, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pak CY, Chu S: A simple technique for the determination of urinary state of saturation with respect to brushite. Invest Urol 11: 211–215, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pak CY: Physicochemical basis for formation of renal stones of calcium phosphate origin: Calculation of the degree of saturation of urine with respect to brushite. J Clin Invest 48: 1914–1922, 1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]