Abstract

Objective

To create and implement improvisational exercises to improve first-year pharmacy students' communication skills.

Design

Twelve 1-hour improvisational sessions were developed and added to an existing/established patient communication course to improve 3 basic skills: listening, observing and responding. Standardized patient examinations were used to evaluate student communication skills, and course evaluations and reflective journaling were used to evaluate students' perceptions of the improvisational exercises.

Assessment

The improvisational exercises markedly improved the students' performance in several aspects of standardized patient examination. Additionally, course evaluations and student comments reflected their perception that the improvisational exercises significantly improved their communication skills.

Summary

Improvisational exercises are an effective way to teach communication skills to pharmacy students.

Keywords: communication, improvisation

INTRODUCTION

The same basic exercises used by improvisational actors to hone their craft have been used to develop professional training programs for students and employees to promote creativity, improve presentation skills, expand team-building skills, and increase comfort with speaking in front of others.1 These exercises are also useful in teaching basic communication skills. Improvisational actors rely heavily on their fellow actors expanding on each others' ideas as they create a scene on stage. They listen carefully while observing body language, paying attention not only to the words but also to the emotional context and subtle inflections. They must do all this while focusing completely on the moment, without anticipating or directing the action and dialog that unfold. Because improvisational training exercises intrinsically focus on the skills of listening, observing, and responding, these exercises can be useful in other training settings, such as pharmacy.

Strong communication skills are essential for the practicing pharmacist. Whether interacting with patients or other health care professionals, pharmacists must communicate effectively to ensure patient safety and optimal health outcomes. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education has recognized the need to teach communication skills to pharmacy students by placing it as an “area of emphasis” in their Standards 2007 (standards 13.3, 17.1, 17.3, 25.7, and 26.3).2 Some colleges and schools of pharmacy offer dedicated courses on communication skills, while others integrate these skills into a variety of courses.3,4 Over 90% of pharmacy schools use role playing and approximately 80% use standardized patients or role playing to assess student competence.3-5 There are few reports in the medical literature that address the use of improvisational skills to improve provider-patient or provider-provider communication skills.6,7 Ballon et al used a combination of improvisational techniques and role playing to simulate the experiences of patients with mental illness.6 Hoffman et al used improvisation techniques to improve first-year medical students' communication skills.7 Neither study evaluated the effectiveness of improvisation in improving specific communication abilities.

While communication skills are emphasized in the admissions process at The University of Arizona College of Pharmacy, we further develop our students' skills beginning with the first semester of the curriculum with an Interviewing and Counseling Skills course. Since fall 2001, the course has undergone several major changes in response to student performance on course examinations. Course testing is done primarily through 2 standardized patient examinations (SPEs) with an instructor serving as the simulated patient. If students do not score better than 75% on the standardized patient examination, they must repeat it until they exceed 75%. During the examinations, students are required to demonstrate minimum competencies with specific interviewing and counseling techniques. In addition, the students must demonstrate the ability to adapt these techniques to real world situations. The instructor, acting as the simulated patient, presents physical symptoms and emotional responses requiring the students to effectively navigate the conversation using a number of skills to capture all of the necessary information and properly address the pateint's emotional state.

By fall 2004, the last of the planned changes were completed. While the changes over the previous 2 years had markedly improved the students' technical performance of the skills (fewer than 5% initially scored less than 75% on their SPE), a majority of students still struggled with how to quickly recognize cues that would tell them when to address the patient's emotional state and new physical symptoms. Students were so focused on the techniques and the gathering of information that they missed the cues given by the standardized patient. In almost all cases, the instructor had to resort to additional or even exaggerated cues before students recognized the need to switch techniques. The instructors decided to introduce improvisational exercises in the course to improve the students' ability to recognize cues and ultimately their performance during the standardized patient examinations as well as in actual practice. This paper describes how improvisation exercises were incorporated into the Interviewing and Counseling Skills course at The University of Arizona College of Pharmacy.

DESIGN

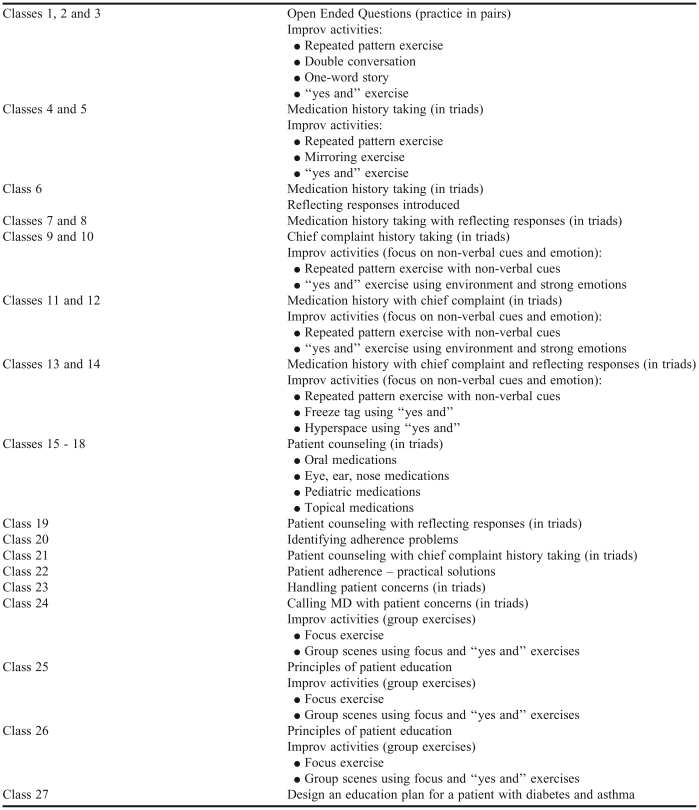

Approximately 90 first-year pharmacy students are enrolled in the Interviewing and Counseling Skills course, which meets for two 2-hour class sessions each week for 16 weeks in the fall semester. The course outline is included in Table 1. Content for the course (Table 1) includes topics such as conducting a complete medication history; conducting a chief complaint history; dealing with upset patients using reflective responses; counseling patients on prescription medications; teaching primary patient education and adherence support skills; communicating with other health professionals; and answering patient questions. The term “chief complaint history” is applied to those skills necessary to evaluate a complaint or symptom presented by the patient during the process of a complete medical history (eg, symptoms of a medication side effect, underlying illnesses, or a new acute problem). The term “reflective response” is used to describe the appropriate process and response for a patient demonstrating an emotional reaction. The course work for each topic consists primarily of a 15-minute lecture on a specific communication skill and practice sessions in groups of 3 (triads) with scripted role playing in which participants apply single or multiple communications skills. In the triads, 1 student plays the pharmacist; another the patient; and the third the evaluator, who provides feedback to the student playing the pharmacist. The roles are rotated among the 3 students during multiple scenarios in each session.

Table 1.

PhPr 804: Interviewing and Counseling Skills Course Outline

With the addition of the improvisational exercises, our goal was to supplement our current course material so students would:

(1) Develop additional expertise in the “art” of basic communication skills such as listening, observing, and responding.

(2) Improve their ability to think on their feet and develop creative ideas quickly.

(3) Understand the importance of emotion and relation (status) in communication.

(4) Become more comfortable communicating in front of large groups.

(5) Recognize the basic dynamics of group communication.

(6) Learn to stay “in the moment,” focusing on the patient or fellow healthcare provider during an encounter, and quickly recognize cues that indicate a need to change communication techniques/approaches, while avoiding the temptation to anticipate.

In fall 2005, 12 hours of improvisation exercises were added to the course content. Prior to each class session that included improvisation, 1 of the authors who had considerable experience and training in improvisational theater spent 5 to 10 minutes training the other course instructors in how to lead the exercises. The training included a brief description of the exercise and its purpose, as well as tips on teaching the skills.

During the semester, the improvisation sessions were used to supplement the existing course content. The students were first given an introduction to the basic principles of improvisation. While they were also advised that many of the exercises would challenge their comfort level, the students were encouraged to approach the exercises with enthusiasm. The goal of the exercises was to focus on the “art” of communication, such as listening, observing, and responding, rather than on specific technical communication skills. During the first year, the improvisation exercises were conducted in six 2-hour sessions, mostly at the beginning of the course. The following year, based on evaluations by the 4 course instructors plus student feedback, the improvisation training was switched to twelve 1-hour sessions integrated more evenly throughout the course. In fall 2007, based on student requests, improvisation training sessions were moved from the first hour of class to the second hour.

On the first day of class, a 20-minute lecture was given before the first improvisation session. The lecture reviewed the rationale behind the exercises and included personal reflections from the instructor with improvisation training. During each subsequent improvisation session, students were divided into 3 or 4 groups of 20-30 students (1 group for each course instructor). The improvisation exercises started with simple skill development and increased in complexity over the semester, which allowed students to incorporate these new skills into the role-play sessions that teach the basic course material. (A complete list of the improvisational activities included in the course is presented in Table 1).

Improvisation Exercises

Repeated Pattern Exercise

The first activity was a repeated pattern exercise, which teaches students listening skills. This activity, led by the instructor assigned to each group, introduced the concepts of focused listening and responding. Group members stood in a circle facing each other. A group member made eye contact with a second group member and called that person's name. This second group member made eye contact with a third group member and called that person's name. The third group member did the same to a fourth group member. The exercise continued until the last group member made eye contact with the first group member (who started the exercise) and called that person's name. At that point, the pattern had been established, and was repeated until the group could demonstrate that they had confidently established the pattern (4 to 5 times).

A second pattern was then started using the names of cities (birth cities, for example, but a city name could be used only once). A different group member initiated the pattern by making eye contact with someone else in the circle (someone different than the person whose name they called previously), then calling the name of a city. The second person did the same with a third person, and so on until the second pattern was established (repeated 4 to 5 times).

Once both patterns were established, they were then initiated simultaneously. The goal was for the group to maintain both patterns. If the group was able to perform both patterns simultaneously, a third pattern could be started using, for example, the name of a type of animal. Each student was responsible for remembering only 2 or 3 simple things. However, the tendency was to focus on the whole pattern and not one's own individual portion of the pattern. Once the students began to block out all the “noise” not related to their 2 or 3 words, they could maintain the patterns. The students learned that to succeed in this exercise, they had to listen for their cues, respond accordingly, and ignore everything else.

Each improvisation session began with the repeated pattern exercise. This helped to focus the group before moving on to more complex exercises. Another benefit to this exercise was that it served as an “ice-breaker” for first-year students by mixing up the groups and compelling the students to interact with their classmates and learn their names.

The reasons for the repeated pattern exercise were multiple. One of the most important goals was to teach students to listen while blocking out distractions. Blocking out distractions and listening carefully is a key skill set that is critical in most pharmacy practice settings. The exercise also taught students to resist the urge to anticipate what a patient or colleague is going to say. Because the pharmacy work environment is often hectic, noisy, and filled with distractions, pharmacists run the risk of hearing what they expect to hear; they may hear an initial comment from a patient and anticipate the follow-up, which can lead to inaccurate conclusions. The purpose of this exercise was to teach students to listen carefully and stay in the moment without thinking ahead.

Advancing a Conversation

Another key improvisation skill practiced throughout most of the exercises was the ability to advance a conversation without asking questions. This was done by using the “yes and…” exercise. Two students stood in front of the class and were told their relationship to one another, their environment, and a topic to discuss. This information was provided either by the instructor or other students. One of the 2 students initiated the conversation by making a simple statement. The second person had to agree with the statement and add to the thought. They did this by starting their statement with the words “Yes and…” The goal was to continue to move the conversation forward and speak for a specified period of time. They could not use questions or deny a statement by saying “no.” Using the word “no” or asking a question created barriers and halted communication. For example:

Student 1 (mother): You're home late. It's 3 in the morning.

Student 2 (son): Yes, and I was at a huge party all night long. You're up late, too.

Student 1: Yes, and I was also at a party. I just got home myself. I am surprised that I beat you home.

Student 2: Yes, and I am surprised you beat me home, too. You are usually out until at least sunrise.

Short Scenarios

The “Yes and…” technique was used to conduct a series of other exercises that involved performing short scenarios. These exercises varied and were designed to teach several concepts. The scenarios stressed the importance of status and emotion in every conversation. For example, to emphasize the importance of status, a student played the role of a king while another student played the role of a servant. Just as the servant was more interested in pleasing the king, patients may try to please their pharmacist by giving answers they think a pharmacist wants to hear. Pharmacists must recognize that behavior when it happens. Emotion also plays a critical role in communication. Someone who is happy will act differently than someone who is sad. To communicate effectively, pharmacists must recognize those emotions. The students were also challenged to play more complicated emotions. Characters were not always either happy or sad; they could be frightened, apprehensive, or feeling some other emotion. The students were required to act in numerous different ways (eg, with apprehension) to act out a variety of emotions so they would be more likely to recognize these emotions and the behaviors associated with them in a patient.

As described in the “Yes and…” exercise, 2 to 3 students would stand in front of the group. The instructor described their assigned relationship, environment, and topic. Then, 1 of the students only was instructed to mimic an emotion (but the others were not told what the emotion was). The goal of the exercise was for the others to recognize and name the emotion. The instructors made sure the students played their roles and that they moved the conversation forward with affirmative or positive statements. The students were not required to say the words “yes and” before each line of dialog, although doing so sometimes helped. The instructor listened to make sure students did not use questions or deny statements by saying “no.”

Group Communication Exercises

The last 4 improvisation sessions focused on the dynamics of group communication. During group communication exercises, the idea of maintaining a single focus was introduced. For group communication to function effectively, only 1 person could speak at a time and while that person was speaking, they were said to have the “focus.” They could be given the focus directly by someone else in the group or they could take the focus. When some else had the focus, all others needed to stop speaking and listen.

This concept was first introduced in a non-verbal exercise. Groups of 10 to 25 students wandered around in a given space. When the course instructor said “Freeze,” the group stopped moving. One person then initiated movement and walked around and through the others. That person had the focus. They could give the focus to another person at any time by making eye contact and freezing in place. The person they gave the focus to then moved around the group until they gave the focus to someone else (nonverbally, through eye contact). The goal was for one and only one student to be moving at all times, with seamless transitions from one student to the next.

Once the group mastered giving the focus to one another, the exercise continued, but this time with someone taking the focus from the person who was moving. To do this, the person wishing to take the focus had to first make eye contact and then begin moving decisively without hesitation. The person who had the focus had to recognize the initiation of movement by the other group member and give up the focus by immediately freezing in place. This emphasized the importance of taking the focus strongly when desired and giving it up when it is taken by another.

Evaluation

Both quantitative (standardized patient examination scoring) and qualitative (student and instructor feedback) data were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the improvisation training. Since the major problem noted in the 2004 standardized patient examinations was failure on the part of the students to recognize initial cues for reflective responses or for taking a chief complaint history during medication history and prescription counseling scenarios, student performance in these areas was chosen as the primary evaluative criteria for the effectiveness of adding the improvisation exercises. Student evaluations and students' reflective journals were also used to analyze the success and effectiveness of the innovation.

ASSESSMENT

Following initial improvements in the Interviewing and Counseling course, the average scores for the first (medication history) standardized patient examination rose from 120 (out of a maximum possible score of 150) in 2002 to 134 in 2004. Almost all of the lost points in 2004 could be attributed to students' failure to initially recognize cues from the standardized patient to either use a reflective response or to use chief complaint history taking. After the implementation of the improvisation exercises, average standardized patient examination scores were 141 in 2005, 143 in 2006, and 144 in 2007. The number of perfect scores (150 points) on the first (medication history) standardized patient examination rose from 1 in 2002 to 5 in 2004, and even further to 21 in 2005, 24 in 2006, and 24 in 2007.

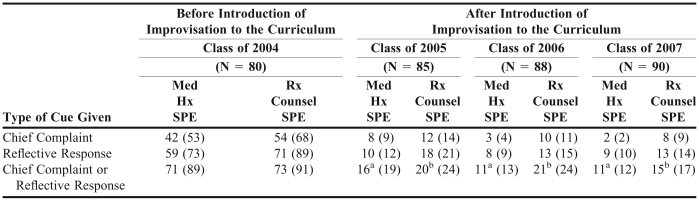

Most of the changes in scores since 2004 reflected not losing the 5 points for failing to recognize initial cues and second cues, or not losing 15 points for failing to provide any reflective responses or conduct chief complaint histories. Table 2 shows the marked improvement over time, manifest as a reduction in the number of students who failed to recognize initial cues. Analysis was conducted comparing each of the 3 years after the improvisation sessions were introduced (2005, 2006, and 2007) and the year prior to their introduction (2004), for students who failed either the chief complaint history taking cue or the reflecting response cue. Significant differences between each of the post-improvisation years (2005, 2006, and 2007) compared to the pre-improvisation year (2004) were found using chi-square tests (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences among the post-improvisation years (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Pharmacy Students Who Failed to Recognize Initial Cues During Standardized Patient Examinations Before and After Introduction of Improvisation Exercises to the Curriculum, No. (%)

Abbreviations: Med = medical; Hx = history; SPE = standardized patient examination; Rx = prescription; Counsel = counseling

ap < 0.001 compared to 2004

bp < 0.001 compared to 2004

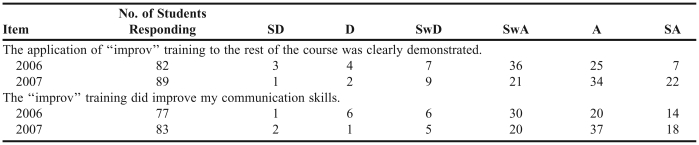

To analyze student course evaluations, responses were grouped as either “disagree” or “agree.” In both 2006 and 2007, a large proportion of students agreed that the application of the training to the rest of the course was clearly demonstrated. Results of chi-square tests comparing the proportion of students agreeing with this statement did not significantly differ from year to year (p = 0.514) (Table 3). A 6-point response scale was used to assess the students' perceptions of how the improvisation skills affected their overall communication skills. Results are also listed in Table 3. As with the previous analysis, responses were made dichotomous: “disagree” or “agree.” In 2006, 83% either somewhat agreed, agreed, or strongly agreed with the statement: “The ‘improv’ training did improve my communication skills.” In 2007, that number increased to 90%. The proportion of students who agreed that their communication skills improved due to training showed no difference from one year to the next (p = 0.175). A review of the students' reflective journal revealed that the majority of students reported positive experiences, although a small percentage were uncomfortable and struggled with the exercises.

Table 3.

Pharmacy Students' Responses to Selected Items From a Questionnaire

Abbreviations: SD = strongly disagree; D = disagree; SwD = somewhat disagree; SwA = somewhat agree; A = agree; SA = strongly agree.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, our use of improvisational exercises to improve pharmacy students' communication skills is the first within the academic pharmacy community. The hope was that the exercises would teach students the “art” of communication. Specifically, we wanted to improve the students' ability to think on their feet, show them the effect that emotion and relationship have on conversation, increase their comfort level with speaking in front of large groups, and teach them to stay in the moment. The improvisational exercises more than met the expectations of the instructors.

Prior to the implementation of the innovation, students performed extremely well using standardized open-ended questions to interview patients. However, this style of questioning puts the entire burden of continuing the conversation on the patient. Some patients may be uncomfortable responding to questions particularly if the pharmacist has not established a rapport with patient. Additionally, patients who may be distracted by other physical symptoms or emotions might not respond to the questions being asked. We believe the improvisation exercises gave the student the skill sets they needed to advance and navigate the conversation when needed.

The “yes and” exercises and short scenarios were successful in training students to think on their feet and develop creative ideas quickly. The students were informed of their relationship to one another, their location (environment), and a topic. Without preparation, they were asked to create a conversation. This forced them to work together, listen carefully for ideas, and then develop those ideas over a 3- to 5-minute scene. By design, these exercises challenged the comfort level of many of the students but prepared them for the challenges they will face in stressful practice settings where they will have to solve multiple complex problems.

The group communication exercises helped the students recognize the importance of give and take in small group settings. While group communication skills can transfer to patient care (eg, in small education classes or while speaking with families), the skills are also related to other settings during the course. For example, group communication is an essential leadership skill because leaders must recognize when it is appropriate to speak and when it is appropriate to be quiet and listen. Meetings are often unproductive when people speak out of turn, but the exercise can help students recognize when they might have “the focus” in a meeting and when they might not. Students can use this skill in many situations, including study groups, discussion sessions, and professional meetings.

As indicated by the course evaluations and reflective journals, efforts to demonstrate the transferability of the improvisational skills have had a positive impact on how students perceive the utility of the improvisation exercises in improving other course skills and overall communication skills. Most of the student comments pointed to the ability of the improvisation skills to help them quickly recognize nonverbal and verbal indications to temporarily stop interviewing or counseling and shift to another skill. There was also an indication of improved ability to deal with unexpected situations and an increased level of comfort in performing and speaking in front of groups. For a small percentage of students, the improvisational exercises challenged their comfort level a little too much. However, the instructors noted that even students who struggled with the exercises had significant improvements in their SPE scores, performing just as well as the students who were more comfortable with the exercises.

The success has been so positive that we strongly encourage other colleges and schools of pharmacy to consider implementing this innovation. The exercises used are introductory improvisational exercises and instructors will find support and training widely available. Live training is available in a number of cities nationwide.1 Additionally, descriptions and examples of improvisation exercises are also available through a number of different Web sites.8-11

Support and expert advice may also be available through university theater arts programs, high school drama groups, and/or local drama groups or comedy troupes. With all of the available resources, teaching innovation should be easily transferrable and easy to implement in any pharmacy school.

SUMMARY

The addition of 12 hours of improvisation exercises to an existing professional communications course markedly improved pharmacy student performance and scores on many aspects of the standardized patient examinations. Course evaluations and reflective journals indicated that students felt that the improvisation sessions had a positive impact on their overall communication skills. Given all the available resources, using improvisation training to improve pharmacy students' communication skills should be considered and could be readily implemented in other colleges of pharmacy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Training Centers. The Second City. Available at: http://www.secondcity.com/?id=training-education. Accessed January 28, 2009.

- 2.Accreditation Standards and Guidelines, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp Accessed January 28, 2009.

- 3.Billow JA. The status of undergraduate instruction in communication skills in U.S. Colleges of Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1990;54:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beardsley RS. Communication skills development in Colleges of Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65:307–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimberlin CL. Communicating with patients: skills assessment in US Colleges of Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70:1–9. doi: 10.5688/aj700367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballon BC, Silver I, Fidler D. Headspace theater: an innovative method for experimental learning of psychiatric symptomatology using modified role-playing and improvisational theater techniques. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31:380–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.5.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman A, Utley B, Ciccarone D. Improving medical student Communications skills through improvisational theatre. Med Educ. 2008;42:537–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Improv: Slow Motion Samurai Exercise, Expert Village. Available at: http://www.expertvillage.com/video/123385_improv-slow-motion-samurai-exercise.htm. Accessed on January 28, 2009.

- 9.Improv and Acting Articles and Tips, Pan Theater. Available at: http://www.pantheater.com/Articles/ImprovArticlesHP.htm. Accessed on January 28, 2009.

- 10.Welcome to learnimprov.com. Available at: http://www.learnimprov.com/. Accessed on January 28, 2009.

- 11.Improv Games, Improv Encyclopedia. Available at: http://improvencyclopedia.org/games/index.html. Accessed on January 28, 2009.