The Certificate in Community Preparedness and Disaster Management (hereafter called CCPDM) is a 12-credit online graduate-level certificate offered by the Department of Health Policy and Management at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Gillings School of Global Public Health in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The CCPDM was developed to provide community leaders in public health, health services, and emergency management with the opportunity to enhance their knowledge of management systems used to prepare for and respond to natural and manmade disasters, including terrorism. Program planners also hoped to provide an impetus for the professionalization of the disaster management field, as well as an opportunity for networking among professionals from the diverse fields involved in disaster management.

The CCPDM is one of eight graduate certificate programs currently offered by the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health.1 The Association of Schools of Public Health website catalogs 51 certificate programs from 20 accredited schools of public health (SPHs) that cover a broad range of topics, including six related to public health preparedness, emergency management, and disaster response.2 Fifteen of these certificate programs are offered via distance learning, and all but one provide course credit toward a graduate degree at the sponsoring university. Available certificate programs require an average of 15 credit hours for completion (range: 8–25). The demand for certificate programs has been fueled by rapid growth in the fields of public health preparedness and disaster management since 2001, and certificate programs have become a way for schools to bring public health and other professionals into academic programs without requiring them to commit to full-time enrollment or relocate.

Cohorts begin the CCPDM each year in July and January and proceed through four courses sequentially, completing the certificate program in approximately 12 months. All coursework is completed online through the Edufolio™ course management system, which includes e-mail capabilities, streaming audio lectures, file sharing, asynchronous discussion forums, and synchronous audio chat sessions. Students are invited to campus for orientation and graduation programs. Credits earned during the certificate program may be transferred to a master of public health (MPH) program.

The four courses include the following:

Community and Public Health Security: Disasters, Terrorism, and Emergency Medical Services (includes topics such as the incident command system; local, state, and national structures for responding to disasters; and the health-care system's response to disasters);

Community and Public Health Disasters: Issues for Action in Business Continuity (includes topics such as biological and chemical agents, radiological threats, food and water safety, and the public health impact of hurricanes);

Emergency Management I: Analytic Methods (includes topics such as forensic epidemiology, risk communication, surveillance systems, program evaluation, and cost-benefit analysis); and

Emergency Management II: Planning and Implementation (includes topics such as the roles of the military and volunteer organizations in disaster response, evacuation, issues in recovery, and mitigation).

Courses are taught by UNC faculty and staff as well as public health practitioners from the North Carolina Division of Public Health.

Certificate programs have become a popular way for SPHs to reach their audience for continuing education. However, little has been published evaluating their impact on either the individuals completing the programs or the organizations that employ them. This article presents evaluation data from the CCPDM.

METHODS

We developed two surveys to measure participant satisfaction with the CCPDM and to measure the success of course developers in meeting goals related to improving participants' perceived ability to perform their roles and administer complex systems during a disaster. The surveys were identical to surveys that had been pilot-tested with other certificate programs at UNC.

We collected all evaluation data from past participants via an e-mail that provided a link to an online survey hosted at SurveyMonkey.com. We sent an initial e-mail and two reminder e-mails. The initial survey collected baseline data from participants directly post-graduation to evaluate participants' immediate satisfaction with the program. The initial survey also contained questions to measure participants' attitudes toward each course, skills gained from the program, and perceived strengths and weaknesses of the program. We also solicited suggestions for improvements.

Six months after graduation, we sent participants an e-mail asking them to complete a six-month follow-up survey, also hosted at SurveyMonkey.com. This survey aimed to evaluate longer-term effects of participation in the CCPDM on individuals, their careers, and their organizations. This survey addressed three hypotheses: (1) that participants used skills from the certificate program to perform tasks in their jobs, (2) that participants received promotions or other recognition at their jobs for completing the certificate program, and (3) that participants' organizations experienced benefits when participants shared course materials with staff who had not enrolled in the certificate program.

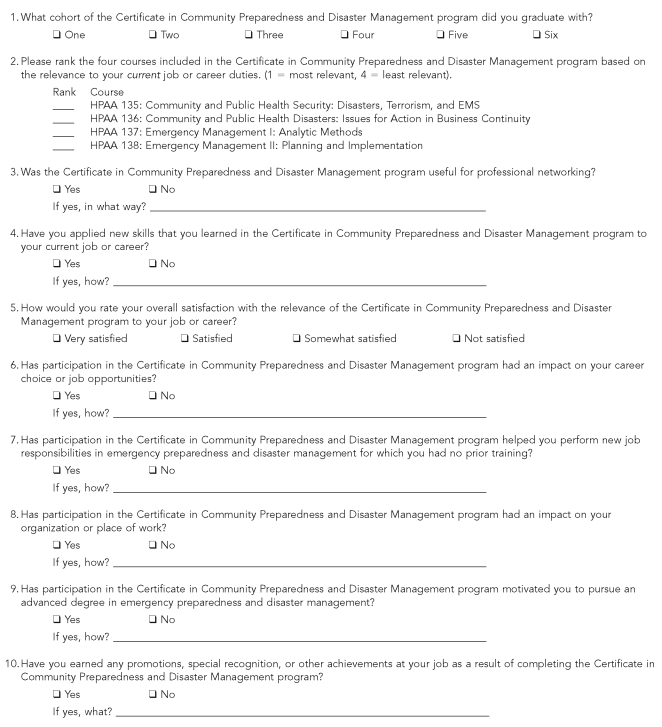

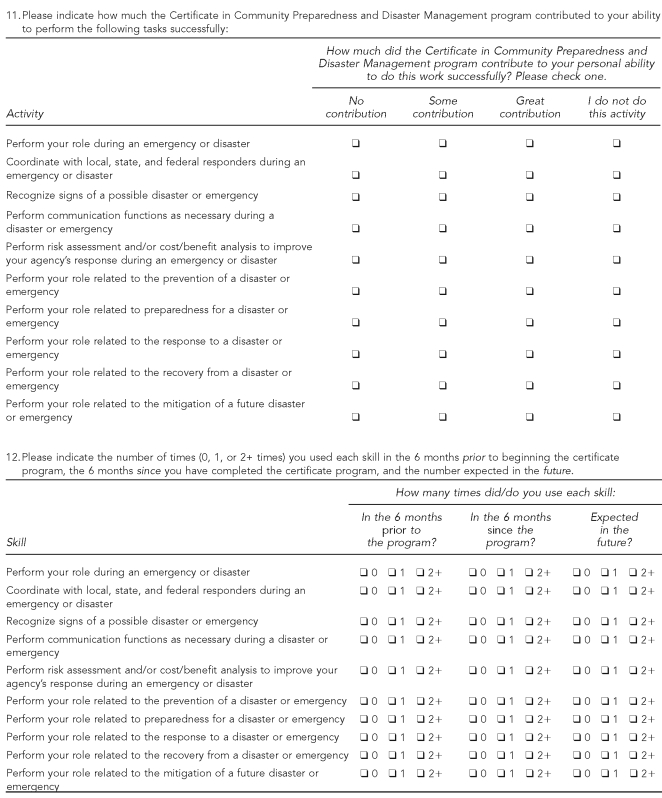

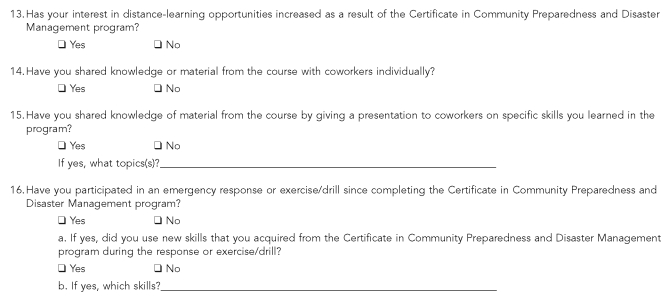

To test these hypotheses, the six-month follow-up survey included questions that addressed perceived relevance of coursework to their current job responsibilities, perceived changes in confidence in performing disaster management tasks, self-reported use of CCPDM skills in a professional capacity (e.g., during emergency responses as well as part of exercises and drills), and attitudes toward sharing the information gained during the certificate program with their colleagues. We also collected data on any promotions or recognitions received for certificate completion, plans for future graduate-level study in disaster management, and dissemination of course materials to others through both informal and formal channels. The complete six-month follow-up survey is shown in the Figure.

Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 completed only the six-month follow-up survey, which was administered six months after Cohort 3 completed the program and 18 and 12 months after Cohorts 1 and 2 completed the program, respectively. Cohorts 4–6 completed the initial survey upon program completion and the follow-up survey six months later.

The Institutional Review Board of UNC at Chapel Hill approved this project.

RESULTS

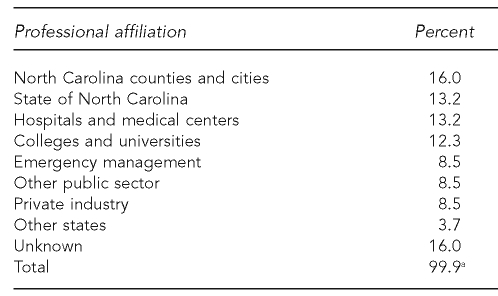

As shown in the Table, the CCPDM draws participants from varied professional affiliations. More than 40% of participants (n=106) in Cohorts 1–6 worked in state, county, or city government, including 16% who were affiliated with North Carolina county and city government agencies and 13% who represented North Carolina state government. Another 13% were affiliated with hospitals and medical centers, while 9% were affiliated with emergency management. The CCPDM enrolls students from a wide geographical area, with 17 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Japan, and Canada represented among the participants.

Disaster management is a diverse field, with professionals from a number of subject matter areas. This certificate program provides students with the opportunity to network with leaders and colleagues from across the spectrum of the disaster management community. The six-month follow-up survey of Cohorts 1–6 had a response rate of 34% (36/106). Respondents and nonrespondents were similar in terms of their professional affiliations, although no other demographic data were available for comparison. In the six-month follow-up survey, 53% of respondents (n=36) indicated that the program improved their ability to coordinate with local, state, and federal responders during an emergency. A majority of participants (83%) agreed that the certificate program was useful in professional networking. One-half of those who completed the six-month follow-up survey indicated that the certificate program influenced their job choices following completion of the program.

Participants also documented changes in their roles within their own organizations following certificate completion. All certificate program graduates who completed the six-month follow-up survey indicated that they had used skills from the CCPDM in their jobs. One-half of the graduates received promotions or special recognition at their jobs as a result of completing the certificate.

Respondents also indicated that they believed their CCPDM work benefited their organizations, beyond their own individual improvements. Two-thirds of certificate program graduates who responded to the follow-up survey indicated an effect from their participation on their organization or workplace. One positive effect may have been sharing the information from the program: all 36 respondents shared materials from the courses with coworkers, and 43% of respondents gave formal presentations to coworkers based on materials from the certificate program.

The professionalization of the disaster management field is another goal of the program. More than 44% of those who completed the survey said they were interested in seeking an advanced degree in emergency preparedness or disaster management. In addition, participation in a distance-learning program made 100% of respondents more willing to pursue other distance-learning opportunities, broadening their options for seeking future training and degree programs.

An additional goal of the CCPDM is to improve participants' ability to administer systems and complex programs during a disaster. Respondents felt that the program helped them better understand their roles during all stages of emergency management and disaster response, with the greatest number reporting improvements related to disaster preparedness (75%). Sixty-four percent indicated that the program improved their ability to perform roles related to responding to a disaster or emergency, while 53% indicated a self-assessed improvement in the ability to perform roles related to the recovery from and mitigation of a disaster or emergency.

Because disasters or other events requiring disaster response cannot be anticipated, exercises and drills are often used to evaluate the knowledge and skills of those trained in disaster management. For most respondents, reported improvements were tested at their jobs through participation in exercises and drills. More than 90% of CCPDM graduates had participated in an emergency response or an exercise or drill -during the six months following program completion. Two-thirds indicated that they used skills acquired in the program during the response or drill.

DISCUSSION

Approximately 40% of respondents to the six-month follow-up survey indicated an interest in seeking an advanced degree in emergency preparedness or disaster management. This is consistent with information from other certificate programs in which approximately one-third to one-half of participants completing a certificate program indicated an interest in pursuing an advanced degree. For example, of students who completed the eight-credit Maternal and Child Health Certificate offered by the Boston University School of Public Health, 32% have enrolled in master's-level programs in public health or related disciplines.3 Sixty-four percent of graduates of the Certificate Program in Core Public Health Concepts at UNC indicated their intention to pursue an MPH degree after completing the certificate,4 while 31% of graduates of the UNC Certificate Program in Field Epidemiology indicated their intention to pursue a graduate degree after certificate completion.5 However, we were not able to determine which respondents already had a graduate degree when they enrolled in these certificate programs.

Support from employers, particularly financial support for tuition assistance or salary increases following certificate completion, may be important in participants' interest in enrolling in certificate programs. But because many participants use certificate education as a means of entering a new field or changing jobs, the incentives for employer support are mixed. For example, 50% of the students who completed the Boston University Certificate changed jobs or changed job descriptions to include expanded responsibilities and authority in their current job.3 For the employer, the former outcome is not an incentive to offer financial support. In our evaluation, one-half of those who completed the six-month follow-up survey indicated that the CCPDM influenced their job choices following the program.

One way for employers to benefit from this type of program is to encourage certificate program participants to share what they have learned with other employees. In our survey, 100% of respondents indicated that they shared materials from their courses with coworkers on an individual basis, but fewer than half indicated that their employers provided opportunities for graduates to share what they had learned through group presentations to coworkers. For employers to benefit from employee participation in these programs, they may have to provide potential students with tuition assistance, incentives to stay in the current position or organization following program completion, and formal opportunities to share knowledge with coworkers.

The opportunity for professional networking with both fellow students and instructors was important for students and may have implications for students' future professional development opportunities, both inside and outside their current organizations. Further exploration of the extent of student networking, network maintenance after program completion, and the tangible benefits gained through the networks may offer insight into the lasting benefits of the professional networking engendered by the program.

Because participation in drills and exercises is a key way to assess and measure competency in disaster management, a formal drill or exercise could serve as a capstone experience for students and provide an additional evaluation opportunity for measuring improvements in students' skills during all stages of emergency management and disaster response. Observation and evaluation of drills and exercises held at the students' own organizations after certificate completion could also be used to demonstrate individual and organizational improvements.

Limitations

This evaluation had several limitations. The response rate for the survey was low (34%, n=36); therefore, caution should be exercised when drawing conclusions based on the responses of so few participants. Although these results may illustrate challenges for workplaces and questions about the impact of certificate program education, these findings cannot be generalized to other programs. Future attempts at program evaluation should consider providing additional reminders or incentives to improve response rates.

CONCLUSION

The CCPDM appears to influence individuals' networking, willingness to train via distance learning, and application of new skills to their professional responsibilities. It is less clear what influence the certificate program is having on the organizations where participants work.

To meet the certificate program's ultimate goal—improving the systems used to prepare for and respond to natural and manmade disasters, including terrorism—this gap between individual and organizational change will have to be closed. This should be possible over time, as more CCPDM graduates enter graduate degree programs, participate in disaster responses, and build strength in their organizations through using and sharing their skills related to disaster management.

While many SPHs are now offering graduate certificate programs, it is unclear what effect this training will have on organizations and individuals in the public health and disaster management workforce. Future research on these programs should evaluate their impact on both individuals and organizations more systematically. For example, materials such as tabletop exercises and disaster response plans could be analyzed systematically, before and after a number of employees have completed such programs, to evaluate whether such training improves the quality of these products for organizations. Such evaluation would require developing a clear rubric for such products and might require adjusting course content to make sure students receive information about such preparedness activities.

At present, certificate programs meet an identified need for retraining those who cannot commit to full-time enrollment, on-campus studies, or relocation to an SPH, and also provide schools with a new market for continuing education products. However, this mutually beneficial arrangement should be questioned if it does not result in real improvements in individual and organizational performance in response to disasters and emergencies.

Figure.

Certificate in Community Preparedness and Disaster Management: six months post-completion evaluation instrument

Table.

Professional affiliations of participants in the Community Preparedness and Disaster Management Certificate Program at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health (n=106)

aThe total percent does not add up to 100 because of rounding errors.

Footnotes

This article was supported by Cooperative Agreement #U90/CCU424255 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health. Certificate programs. [cited 2008 Sep 12]. Available from: URL: http://www.sph.unc.edu/general/certificate_programs.html.

- 2.Association of Schools of Public Health. Search for a member school: results. [cited 2008 Sep 12]. Available from: URL: http://www.asph.org/document.cfm?page=773.

- 3.Bernstein J, Paine LL, Smith J, Galblum A. The MCH Certificate Program: a new path to graduate education in public health. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5:53–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1011349902582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis MV, Fernandez CP, Porter J, McMullin K. UNC certificate program in core public health concepts: lessons learned. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12:288–95. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200605000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald PD, Alexander LK, Ward A, Davis MV. Filling the gap: providing formal training for epidemiologists through a graduate-level online certificate in field epidemiology. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:669–75. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]