Abstract

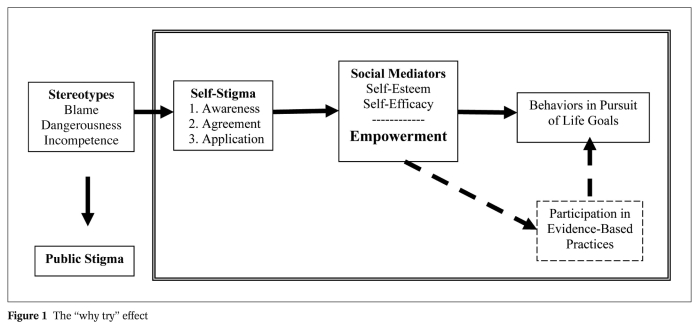

Many individuals with mental illnesses are troubled by self-stigma and the subsequent processes that accompany this stigma: low self-esteem and self-efficacy. “Why try” is the overarching phenomenon of interest here, encompassing self-stigma, mediating processes, and their effect on goal-related behavior. In this paper, the literature that explains “why try” is reviewed, with special focus on social psychological models. Self-stigma comprises three steps: awareness of the stereotype, agreement with it, and applying it to one’s self. As a result of these processes, people suffer reduced self-esteem and self-efficacy. People are dissuaded from pursuing the kind of opportunities that are fundamental to achieving life goals because of diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy. People may also avoid accessing and using evidence-based practices that help achieve these goals. The effects of self-stigma and the “why try” effect can be diminished by services that promote consumer empowerment.

Keywords: Self-stigma, mental illness, public stigma, self-esteem, self-efficacy, empowerment

Social inclusion, recovery, and community reintegration have been interchangeably touted as the main principles of the mental health system in the new millennium 1, 2,3, 4. Common to these ideas is accomplishing self-determined goals that enhance one’s sense of well being. These kinds of goals are defined in the here and now, and are framed in terms of real interests of all adults, those with as well as without disabilities. Relevant domains include: vocation, housing, education, health and wellness, relationships and recreation, and faith-based aspirations. Functional limitations due to one’s disability negatively impact the ability to fully achieve goals in these domains. Participation in evidence-based practices supports the achievement of life goals. Stigma seems to perniciously affect goal attainment and undermines positive effects of evidence-based practices.

How does stigma affect personal life goals? Stigma and its effects are distinguished into two forms, public and self-stigma. Consistent with a social psychological model, public stigma has been described in terms of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Social psychologists view stereotypes as knowledge structures that are learned by most members of one social group about people in different groups 5. Stereotypes about mental illness include blame, dangerousness, and incompetence 6. The fact that most people have knowledge of a set of stereotypes does not imply that they agree with them 5, 7. People who are prejudiced endorse these pejorative stereotypes (“That’s right; all persons with mental illness are violent!”) and generate negative emotional reactions as a result (“They all scare me!”) 8, 9. Prejudice leads to discrimination, the behavioral reaction 10. Discrimination that comes from public stigma emerges in three ways: loss of opportunities (e.g., not being hired or leased an apartment), coercion (an authority makes decisions because the person is believed to be unable to do so), and segregation (what was previously moving people to state hospitals has now manifested itself as mental illness ghettos, especially pronounced in many urban settings) 11. This chain of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination is public stigma, the way in which the general public conceives of and reacts to people with serious mental illness. This is to be distinguished from self-stigma and the “why try” effect which is at the heart of this paper.

THE “WHY TRY” MODEL

The “why try” effect includes three components: self-stigma that results from stereotypes; mediators such as self-esteem and self-efficacy; and life goal achievement, or lack thereof. An important program of research has framed self-stigma and parts of the “why try” effect as modified labeling theory 12, 13. People who internalize stereotypes about mental illness experience a loss of self-esteem and self-efficacy 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. People labeled with mental illness who live in a culture with prevailing stereotypes about mental illness may anticipate and internalize attitudes that reflect devaluation and discrimination. Devaluation is described as awareness that the public does not accept the person with mental illness. A subsequent body of research has sought to expand modified labeling theory 19, 20, 21. Self-devaluation is more fully described by what are called the “three A’s” of self-stigma: awareness, agreement, and application.

To experience self-stigma, the person must be aware of the stereotypes that describe a stigmatized group (e.g., people with mental illness are to blame for their disorder) and agree with them (that’s right, people with mental illness are actually to blame for their disorder). These two factors are not sufficient to represent self-stigma, however. The third A is application. The person must apply stereotypes to one’s self (I am mentally ill so I must be to blame for my disorder) 21. This perspective represents self-stigma as a hierarchical relationship; a person with mental illness must first be aware of corresponding stereotypes before agreeing with them and applying self-stigma to one’s self. Note that the definition of self-stigma presented in Figure 1 is limited to perceptual-cognitive processes. As Goffman 22 argued, stigma is fundamentally a cue that elicits subsequent prejudice and discrimination.

Figure 1.

SELF-ESTEEM AND SELF-EFFICACY

Consistent with modified labeling theory, the demoralization that results from self-stigma leads to reduced self-esteem. In turn, the mediating role of self-esteem on several proxies of goal attainment has been tested and confirmed in four studies 23, 24, 25, 26; goal attainment proxies include symptom reduction and quality of life. Measures of contingent self-worth were positively associated with financial and academic problems 25. Rosenfield and Neese-Todd 25 also showed that specific domains of quality of life – satisfaction with work, housing, health, and finance – were associated with self-stigma as well as self-esteem. Self-stigma and self-esteem have also been associated with actual help-seeking behavior, an important focus of research because of its implications 26.

The “why try” effect further develops modified labeling theory by including another important mediator, which is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a cognitive construct that represents a person’s confidence in successfully acting on specific situations 27. Low self-efficacy has been shown to be associated with the failure to pursue work or independent living opportunities at which people with mental illness might otherwise succeed 12, 13, 18, 20, 25, 28, 29. Consider findings from two studies as examples. In the first, Carpinello et al 30 showed that people with mental illness with low degrees of confidence in managing various circumstances related to their mental illness were found to be unsuccessful in discrete attempts to realize corresponding goals. Second, a path between stigma, efficacy, and goal attainment was implied in a study of people with serious psychiatric disabilities 29. Results showed that a measure of self-stigma was associated with self-efficacy, which then corresponded with low quality of life, the goal proxy.

Modified labeling theory outlines the behavioral consequence of devaluation; namely the person may avoid situations where he/she is going to feel publicly disrespected because of self-stigma and low self-esteem. Behavioral consequences in the “why try” model exceed notions such as social avoidance. People who agree with stigma and apply it to themselves may feel unworthy or unable to tackle the exigencies of specific life goals. One might think that beliefs like these arise because the person indeed lacks basic social and instrumental skills to accomplish a specific aspiration. Alternatively, lack of confidence may reflect doubts thrown up by agreeing with specific stereotypes and defining one’s self in terms of those stereotypes. “Why should I even try to get a job? Someone like me − someone who is incompetent because of mental illness − could not successfully accomplish work demands”.

Self-stigma effects on one’s sense of self-esteem also yield “why try” responses. A person who has internalized stereotypes like “the mentally ill have no worth because they have nothing to offer and are only drains on society” will struggle to maintain a positive self-concept. Self-worth here is more than the kind of negative self-statements that are observed in people with depressive symptoms. It is directly linked to applying a derogatory stereotype to one’s self. “Why should I even try to live independently? Someone like me is just not worth the investment to be successful”.

Unclear is whether these constructs − self-esteem and self-efficacy − overlap considerably as evaluative components of self-stigma or are independent in their effects. Findings from one study supported the latter, namely that self-esteem and self-efficacy were independently associated with satisfaction in financial goals 15. It is conceivable that a person can feel efficacious in a particular situation that has no effect on self-esteem. A person may be confident in getting to work each day but feel this is not an especially important part of work; as a result these efficacy effects will have little impact on self-esteem 27.

EMPOWERMENT

To this point, the model of self-stigma and social psychological constructs describes negative processes that arise from self-stigma. Personal empowerment is a parallel positive phenomenon conceived as a mediator between self-stigma and behaviors related to goal attainment. Results of an exploratory factor analysis of 261 responses yielded five factors that describe the construct 31, 32, 33. Four of these factors delineate the content of the idea: power and powerlessness; community activism; righteous anger about discrimination; and optimism and control over the future. A fifth factor – good self-esteem and self-efficacy – shows empowerment to anchor one end of a self-stigma continuum, with self-esteem and self-efficacy at the other. This evinces a fundamental paradox that explains the two ends of the continuum 34. Some people internalize the stigmatized message and suffer diminished self-esteem and lowered self-efficacy. Others seem to be energized by the same stereotypes and become empowered in reaction to them 31, 35. People with this sense of power are more confident about the pursuit of individual goals. They also play a more active role in treatment, crafting interventions that meet their perceptions of strengths, weaknesses, and needs.

What evidence is there that empowerment is the obverse of self-stigma? Several studies have examined correlations between empowerment and other psychosocial measures including self-esteem, self-efficacy, and measures of hope and recovery. Rogers et al 31 found empowerment to be associated with high self-esteem, quality of life, social support and satisfaction with mutual-help programs. Another study 35 found a link between self- and community orientations to empowerment and intact self-esteem. Self-orientation was in addition related to social support and quality of life. In a Swedish study, empowerment was associated with quality of life, intact social networks and high social functioning 36. Empowerment was further related to most aspects of recovery from serious mental illness 37, 38 and inversely correlated with self-esteem decrement due to self-stigma and social withdrawal after controlling for depression 20.

Two factors seem to explain why some people respond to stigma with low self-esteem while others react with righteous indignation 34. People who view the stereotype that corresponds with self-stigma as legitimate suffer greater harm to self-esteem and self-efficacy. Those who do not agree with stereotypes are likely to be indifferent or righteously angry in place of self-stigma. Group identity also affects reactions to stigma. One might think that persons who identify with or otherwise belong to stigmatized groups may internalize the negativity aimed at that group and hence have worse effects to self-stigma. Research shows, however, that persons who develop a positive identity by interacting with members of their ingroup can develop more positive self-perceptions 39, 40. They are less likely to experience diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy as a result.

GOAL ATTAINMENT AND EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES

Up to now, Figure 1 frames goal attainment rather simplistically as a direct outcome of either diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy, or enhanced empowerment. Absent from this model has been the concomitant impact of services that, based on sufficient research, are expected to facilitate many goals. Self-stigma, however, is also likely to impact evidence-based practices. Research from a variety of mental health disciplines have defined evidence-based priorities, including psychiatry 41, 42, social work 43, and psychology 44. Interventions for adults with mental illness that have survived rigorous reviews include medication use, assertive community treatment (which helps people with psychiatric disabilities live independently) 45, supported employment and education (provide the person with basic resources and support so he or she might obtain/retain work or achieve educational goals) 46, and family psychoeducation and support (help family members develop methods that diminish stressful interactions among relatives) 47. Evidence-based practices also include integrated treatment for dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance abuse 48, 49.

How might stigma mediate with the ideas laid out in Figure 1? “Why try” once again elaborates on modified labeling theory by outlining the effects of low self-esteem and self-efficacy on service participation 26. “Why should I try vocational rehabilitation? I am unable to participate in this kind of service”. “Why should I pursue education? Someone like me is not worthy of such a goal”. Similarly, empowerment enhances service utilization and goal attainment. People who determine their own goals and self-select from life opportunities as a result are likely to be more energized and hopeful about their treatment and personal aspirations. Collaborative and self-directed services support empowerment and advance goal attainment 50.

ADDRESSING THE “WHY TRY” EFFECT BY CHALLENGING SELF-STIGMA

Advocates have long recognized the pernicious effects of stigma and have begun to develop strategies meant to counter them. Researchers have then partnered with advocates to evaluate the impact of specific strategies. The “why try” model outlined herein may also be a useful heuristic for identifying and subsequently evaluating self-stigma modification approaches.

Empowerment is an especially relevant and important mechanism for change, because it prescribes what “might be done” to influence goals, rather than “what should not be done” to achieve these goals. This kind of affirmative approach to behavior change is typically more successful than a dysfunction-focus to change 27. The goal here is not to take away stigma, but instead to foster empowerment which enhances the pursuit of life goals and the participation in evidence-based practices related to these goals. Research has begun to examine strategies and interventions that facilitate empowerment in this fashion 51, 52. Some examples are discussed here.

Consumer operated services

Empowerment is endorsed as central to consumer operated services, with its relationship to these services being complex and recursive. Two ingredients of consumer operated services have obvious relevance to empowerment and the “why try” effect. The peer principle represents relationships among members without any sense of hierarchy. As peers, no one is viewed as subordinate and all are encouraged to participate in the consumer operated service in ways that best meet their needs and interests. Related to this perspective is the helper principle. Individuals as helpers are aides, sharing with peers the strategies and resources that they have found useful in addressing life goals blocked by the mental illness. These kinds of experiences enhance the person’s self-efficacy; the person is reminded that he or she is competent in many important social situations because of life experience. The helper principle also augments self-esteem; the person has successful experiences which enhance his or her sense of worth in the community.

Consumer operated services typically assume one of three forms 53. The first is drop-in centers 54, 55. These kinds of programs offer venues where people with mental illness can come and go without the threats and demands of more traditional outpatient services. A second type of consumer operated services is peer support and mentoring services 56, 57. One such example is GROW, which has developed a 12-step written program that guides members through various “stages on the way to recovery”. The third type of consumer operated services is educational programs which seek to teach participants the basic social and coping skills needed for personal success 58. These kinds of programs often have a special focus on advocacy, the skills people need to affect their individual services plan as well as the profile of services in their community 59. Overall, research has shown that the frequency of different kinds of consumer operated services across the US has exploded, with one recent national survey identifying 7467 individual examples 60.

Group identity

As suggested earlier in the paper, another way to influence self-stigma and the “why try” effect is through group identity. People engage in activities that directly implicate their group identity in everyday life, e.g. participate in treatment, mutual-help groups, or mental health advocacy activities. A recent study 21 found a positive correlation between group identification and self-efficacy in people with mental illness. The same study failed to show such a correlation with self-esteem. These are complex relationships, however. In another study 61, group identification did not predict self-esteem or empowerment after controlling for depression, but group identification was negatively related to self-esteem.

Data from other social psychological research support the idea that group identification can be a two-edged sword, in this case, for members of stigmatized ethnic minorities 62. In one study 63, women who received negative feedback on a speech from a male evaluator were subsequently told that the evaluator was either sexist or non-sexist. Women with low gender-identification showed higher self-esteem in the sexist condition, because they could attribute negative feedback to the sexism of their evaluator. However, this did not help highly gender-identified women who showed low self-esteem in both conditions. Therefore, when social identity is a core aspect of one’s self-concept, individuals seem to become more vulnerable to stigmatizing threats related to this group identity. In a second study 63, Latin American students were randomly exposed to a text describing pervasive prejudice against their ingroup, or to a control article. In the control group, baseline ethnic group identification was positively related to self-esteem. However, in the group experiencing the stigmatizing threat, group identification was associated with depressed affect and low self-esteem.

Different reasons could explain these apparent contradictions. If people identify with their ingroup and at the same time hold it in high regard, group identification is likely to be associated with high self-esteem. If, on the contrary, an individual holds a negative view of his/her ingroup, strong group identification may lead to lower self-esteem. These positive and negative views may reflect perceived legitimacy 61. In terms of reducing self-stigma and empowerment among persons with mental illness, it is therefore important to acknowledge the risks of identifying with a negatively evaluated ingroup. Instead, the goal should be to build a positive group identity. Only the latter is likely to help individuals overcome self-stigma.

Coming out

Many people with serious psychiatric disorders opt to avoid self-stigma, thereby diminishing the “why try” effect, by keeping their experience with mental illness and corresponding treatment a secret. Choosing to participate in consumer operated services presumes a personal decision about coming out into the public with one’s mental illness 64. This may be a narrow decision only letting the handful of people in the consumer operated service know of one’s background. Conversely, it may be one small step in being totally out, where the person with serious mental illness broadcasts his/her experiences. Note that coming out may not only include disclosure about one’s personal experiences with mental illness, but also about encounters with the treatment system. Knowing that someone takes a “pill for mental illness” can be as stigmatizing as awareness that the person is occasionally depressed.

The costs and benefits of coming out vary based on personal goals and decisions. Hence, only persons faced by these decisions are able to consider the costs, benefits, and implications. Prominent disadvantages to coming out include disapproval from co-workers, neighbors, fellow church goers, and others when they become aware of the person’s psychiatric background. In turn, this disapproval leads to social avoidance. Benefits include the sense of well-being that occurs when the person no longer feels he or she must stay in the closet. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list; people are likely to identify additional consequences when individually considering the costs and benefits.

Coming out is not a black or white decision based on the assumption that the person is either out or not. Actually, coming out decisions can be addressed by an array of options. In an ethnographic study of 146 people with mental illness, Herman 64 identified several specific ways in which people might disclose. Based on other qualitative research with mental health advocates 65, 66, her work summarized four levels of disclosure.

At the most extreme level, people may stay in the closet through social avoidance. This means keeping away from situations where people may find out about one’s mental illness. Instead, they only associate with other persons who have mental illness. A second group may choose not to avoid social situations but instead to keep their experiences a secret from key agents. When using selective disclosure, people differentiate a group of others with whom private information is disclosed versus a group from whom this information is kept secret. People with mental illness may tell peers at work of their disabilities but choose to not make disclosures like these to neighbors.

While there may be benefits of selective disclosure such as an increase in supportive peers, it is still a secret that could represent a source of shame 20. People who choose indiscriminant disclosure abandon the secrecy altogether. They choose to disregard any of the negative consequences of people finding out about their mental illness. Hence, they make no active efforts to try to conceal their mental health history and experiences. Broadcasting one’s experience means purpose-fully and strategically educating people about mental illness. The goal here is to seek out people to share past history and current experiences with mental illness. Broadcasting has additional benefits compared to indiscriminant disclosure. Namely, it fosters a sense of power over the experience of mental illness and stigma.

CONCLUSIONS

“Why try” is a complex construct which has been defined here in terms of four interacting processes. It begins as the personal reaction to the stereotypes of mental illness; people who in some way internalize these attitudes. The depth of self-stigma depends on whether people are aware of and agree with these attitudes and then apply the stereotypes to themselves. Such personal applications undermine the person’s sense of self-esteem and self-efficacy. These kinds of decrements fail to promote the person’s pursuits of behaviors related to life goals. As a result, people with mental illness decide not to engage in opportunities that would hasten work, housing, and other personal aspirations. “Why try” is also useful for understanding how unwillingness to obtain mental health services affects life opportunities.

Alternatively, reactions to stigma may evoke personal empowerment, the self-assurance that these stereotypes are not going to prevent the pursuit of individually-defined goals. Generally, these models of self-stigma are fruitful for understanding change strategies meant to decrease stigma’s impact. More specifically, principles of empowerment suggest changes to the person and the mental health system which attack self-stigma and promote goal attainment. These include consumer operated services that encourage the development of personal identity with peers with mental illness. They also include explicit decisions about coming out.

Acknowledgements

Nicolas Rüsch was supported by a Marie Curie Outgoing International Fellowship of the European Union.

References

- 1.President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Washington: US Government Printing Office; Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America . 2003

- 2.United States Surgeon General. Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. 1999

- 3.United States Department of Labor. Washington: US Department of Labor; Rehabilitation act amendments (PL 105-220) 1998

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Washington: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; SAMHSA action plan: mental health systems transformation. 2006

- 5.Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Ann Rev Psychol. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrigan PW, Kleinlein P. The impact of mental illness stigma. In: Corrigan PW, editor. On the stigma of mental illness: practical strategies for research and social change. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:529–539. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devine PG. Prejudice and out-group perception. In: Tesser A, editor. Advanced social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 467–524. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilton JL, von Hippel W. Stereotypes. Ann Rev Psychol. 1996;47:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, editors. The handbook of social psychology, Vol. 2 (4th ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrigan PW. On the stigma of mental illness: practical strategies for research and social change. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Soc Rev. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link BG. Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. Am Soc Rev. 1982;47:202–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J. The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. Am J Soc. 1987;92:1461–1500. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markowitz FE. The effects of stigma on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of persons with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39:335–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121(Suppl. 18):31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenfield S. Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. Am Soc Rev. 1997;62:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2006;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rüsch N, Hölzer A, Hermann C. Self-stigma in women with borderline personality disorder and women with social phobia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:766–773. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000239898.48701.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Larson JE. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz FE. Modeling processes in recovery from mental illness: relationships between symptoms, life satisfaction, and self-concept. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:64–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owens TJ. Two dimensions of self-esteem: reciprocal effects of positive self-worth and self-deprecation on adolescent problems. Am Soc Rev. 1994;59:391–407. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenfield S, Neese-Todd S. Why model programs work: factors predicting the subjective quality of life of the chronic mentally ill. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. 1993;44:76–78. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. The anatomy of stages of change. Am J Health Prom. 1997;12:8–10. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gecas V. The social psychology of self-efficacy. Ann Rev Soc. 1989;15:291–316. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M. Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carpinello SE, Knight E, Markowitz FE. The development of the Mental Health Confidence Scale: a measure of self-efficacy in individuals diagnosed with mental disorders. Psychiatr Rehab J. 2000;23:236–243. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML. A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1042–1047. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corrigan PW. Empowerment and serious mental illness: treatment partnerships and community opportunities. Psychiatr Quart. 2002;73:217–228. doi: 10.1023/a:1016040805432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson G, Lord J, Ochocka J. Empowerment and mental health in community: narratives of psychiatric consumer/survivors. J Comm App Soc Psychol. 2001;11:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corrigan PW, Faber D, Rashid F. The construct validity of empowerment among consumers of mental health services. Schizophr Res. 1999;38:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansson L, Björkman T. Empowerment in people with a mental illness: reliability and validity of the Swedish version of an empowerment scale. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corrigan PW, Salzer M, Ralph RO. Examining the factor structure of the recovery assessment scale. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:1035–1041. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corrigan PW, Giffort D, Rashid F. Recovery as a psychological construct. Commun Ment Health J. 1999;35:231–239. doi: 10.1023/a:1018741302682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter JR, Washington RE, Rashid F. Minority identity and self-esteem. Ann Rev Soc. 1993;19:139–161. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frable DES, Wortman C, Joseph J. Predicting self-esteem, well-being, and distress in a cohort of gay men: the importance of cultural stigma, personal visibility, community networks, and positive identity. J Personal. 1997;65:599–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Psychiatric Association. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; Practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: Compendium 2006. 2006

- 42.Corrigan PW, Mueser KT, Bond GR, editors. Principles and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation: an empirical approach. New York: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibbs L, Gambrill E. Evidence-based practice: counterarguments to objections. Res Soc Work Pract. 2002;12:452–476. [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol. 2006;61:271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Salyers MP, Tsemberis S. ACT and recovery: integrating evidence-based practice and recovery orientation on assertive community treatment teams. Commun Ment Health J. 2007;43:619–641. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE. Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:313–322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:903–910. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A. Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:469–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drake RE, Mueser KT, Mueser KT, Brunette MF. Management of persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: program implications. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:131–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Commun Ment Health J. 2006;42:87–105. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corrigan PW. Am Rehab. Autumn; 2004. Guidelines for enhancing personal empowerment of people with psychiatric disabilities; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corrigan PW, Garman AN. Considerations for research on consumer empowerment and psychosocial interventions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:347–352. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, editors. On our own, together: peer programs for people with mental illness. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schell B. Mental Health Client Action Network (MHCAN), Santa Cruz, California. In: Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, editors. On our own, together: peer programs for people with mental illness. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elkanich JM. Portland Coalition for the Psychiatrically Labeled. In: Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, editors. On our own, together: peer programs for people with mental illness. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. pp. 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keck L, Mussey C. GROW In Illinois. In: Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, editors. On our own, together: peer programs for people with mental illness. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitecraft J, Scott J, Rogers J. The Friends Connection, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In: Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, editors. On our own, together: peer programs for people with mental illness. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. pp. 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hix L. BRIDGES in Tennessee: Building recovery of individual dreams and goals through education and support. In: Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, editors. On our own, together: peer programs for people with mental illness. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sangster Y. Advocacy Unlimited, Inc., Connecticut. In: Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, editors. On our own, together: peer programs for people with mental illness. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. pp. 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldstrom ID, Campbell J, Rogers JA. National estimates for mental health mutual support groups, self-help organizations, and consumer-operated services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, Special Issue: Depression in Primary Care. 2006;33:92–103. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-0019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rüsch N, Lieb K, Bohus M. Self-stigma, empowerment, and perceived legitimacy of discrimination among women with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:399–402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Major B. New perspectives on stigma and psychological well-being. In: Levin S, van Laar C, editors. Stigma and group inequality: social psychological perspectives. Philadelphia: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCoy SK, Major B. Group identification moderates emotional responses to perceived prejudice. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29:1005–1017. doi: 10.1177/0146167203253466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herman NJ. Return to sender: reintegrative stigma-management strategies of ex-psychiatric patients. J Contemp Ethnography. 1993;22:295–330. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Corrigan PW, Lundin R, editors. Don’t call me nuts! Coping with the stigma of mental illness. Chicago: Recovery Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corrigan PW, Matthews AK. Stigma and disclosure: implications for coming out of the closet. J Ment Health. 2003;12:235–248. [Google Scholar]