Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a new component of the brain renin-angiotensin system, has been suggested to participate in the central regulation of blood pressure (BP). To clarify the relationship between ACE2 and other brain renin-angiotensin system components, we hypothesized that central angiotensin II type 1 receptors reduce ACE2 expression/activity in hypertensive mice, thereby impairing baroreflex function and promoting hypertension. To test this hypothesis, chronically hypertensive mice (RA) with elevated angiotensin II levels were treated with losartan (angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker) or PD123319 (angiotensin II type 2 antagonist; 10 mg/kg per day, SC) for 2 weeks. Baseline spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity and brain ACE2 activity were dramatically decreased in RA compared with nontransgenic mice, whereas peripheral ACE2 activity/expression remained unaffected. Losartan, but not PD123319, increased central ACE2 activity, spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity, and normalized BP in RA mice. To confirm the critical role of central ACE2 in BP regulation, we generated a triple-transgenic model with brain ACE2 overexpression on a hypertensive RA background. Triple-transgenic–model mice exhibit lower BP and blunted water intake versus RA, suggesting lower brain angiotensin II levels. Moreover, the impaired spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity, parasympathetic tone, and increased sympathetic drive, observed in RA, were normalized in triple-transgenic–model mice. These data suggest that angiotensin II type 1 receptors inhibit ACE2 activity in RA mice brain, thus contributing to the maintenance of hypertension. In addition, overexpression of ACE2 in the brain reduces hypertension by improving arterial baroreflex and autonomic function. Together, our data suggest that angiotensin II type 1 receptor–mediated ACE2 inhibition impairs baroreflex function and support a critical role for ACE2 in the central regulation of BP and the development of hypertension.

Keywords: angiotensin, baroreflex, blood pressure, transgenic mice, nervous system

It is well established that tissue renin-angiotensin systems (RASs) play an important role in the regulation of blood pressure (BP), and hyperactivity of these systems results in the development and maintenance of hypertension.1 Angiotensin (Ang) II, the major actor of the RAS, acts via 2 receptor subtypes: Ang II type 1 (AT1R) and type 2 (AT2R) receptors. Activation of AT1R leads to elevated BP through vasoconstriction, increased cardiac output, aldosterone release, and sodium reabsorption. In addition to these peripheral effects, AT1R also mediates the central effects of Ang II, including vasopressin release, water and salt intakes, and increased sympathetic drive, contributing to the development of high BP. However, Ang II binding to the AT2R is thought to counteract the AT1R-mediated effects.2,3 In the brain, AT2R overexpression has been reported to decrease nocturnal BP and norepinephrine excretion partially by reducing sympathetic outflow.4 Ang-converting enzyme (ACE) 2, a homologue of ACE, is a newly identified component of the RAS.5 The key role of this carboxypeptidase is to cleave Ang II into the vasodilatory peptide Ang-(1–7),6 which, in turn, binds the Mas receptor7 to exert opposite properties to Ang II.

The arterial baroreceptor reflex is the most important autonomic reflex providing beat-to-beat short-term regulation of BP. Arterial baroreceptors located in large arteries sense BP and relay the information to the central nervous system (CNS), where a network of brain stem nuclei adjust sympathetic and parasympathetic activity to modulate vascular resistance and heart rate (HR).8 Interaction of Ang II with brain stem AT1R has been shown to reduce baroreflex sensitivity,9 thus contributing to the development of hypertension. Although AT2Rs have been identified in brain stem nuclei involved in BP regulation,10 their participation in the modulation of baroreflex function remains obscure. On the other hand, Ang-(1–7) has been shown to stimulate the bradycardic component of the baroreflex11 via interaction with Mas.12

We previously showed the presence of ACE2 in the mouse brain, including in regions involved in the central regulation of cardiovascular function.13 Recently, Diz et al14 reported that pharmacological inhibition of ACE2 in the dorsal brain stem resulted in the reduction of the reflex bradycardia in anesthetized rats, suggesting the importance of this enzyme in the central regulation of BP. Although ACE2 has been shown to be regulated by AT1R in the periphery,15 there are no data available regarding such interaction in the CNS. In addition, most of the studies assessing the effects of Ang-(1–7) on baroreflex function have been performed in anesthetized rats. Therefore, we first investigated the relation between central AT1R and ACE2 in conscious unrestrained hypertensive mice. We hypothesized that AT1Rs in the brain of chronically hypertensive mice reduce ACE2 activity, thus impairing baroreflex function and contributing to the maintenance of hypertension. Our study shows that central ACE2 activity is reduced in chronically hypertensive mice and is associated with impaired baroreflex sensitivity. In addition, using a triple-transgenic mouse model, we show that ACE2 overexpression in the CNS restores baroreflex function and contributes to the reduction of hypertension. Our results establish the importance of central ACE2 in the preservation of baroreflex function and its potential in the prevention of hypertension, thus confirming ACE2 as a potential target for the treatment of hypertension.

Materials and Methods

An expanded Materials and Methods section is available in the online data supplement (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Transgenic Mice and Animal Husbandry

Experiments were performed in adult (10 to 12 weeks of age; 25 to 30 g) transgenic and chronically hypertensive mice (RA).16 In additional experiments, these mice were bred with syn-hACE2 transgenic mice with CNS-targeted ACE2 overexpression,17 to generate a triple-transgenic model (SARA) with chronic overexpression of Ang II and brain hACE2. Transgenic mice were kindly provided by (hRen and hAGT) or generated in collaboration with (syn-hACE2) Dr Curt D. Sigmund at the University of Iowa. All mice were bred into a C57BL/6J genetic background beyond 7 generations. Animals were fed standard mouse chow and water ad libitum. All of the procedures were approved by the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Animal Care and Use Committee and are in agreement with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Physiological Recordings

Baseline BP was measured in RA, SARA, and nontransgenic (NT) mice for 3 to 6 days using radiotelemetry, as described.18

RA and NT mice were then randomly divided into 3 groups (n=12 per group); infused SC with the AT1R antagonist losartan (10 mg/kg per day), AT2R antagonist PD123319 (10 mg/kg per day), or vehicle (0.9% saline) for 2 weeks; and then tissues were collected for the following assays. Spontaneous baroreceptor reflex sensitivity (SBRS), reflecting the baroreflex control of HR, was calculated using the sequence method as described.19,20

Autonomic function was assessed using a pharmacological method involving IP injection of propranolol (β-blocker, 4 mg/kg), atropine (muscarinic receptor blocker, 1 mg/kg) and chlorisondamine (ganglionic blocker, 10 mg/kg).21 Changes in HR (ΔHR) were calculated after administration of these blockers. Water intake was recorded daily as described.22

ACE2 Activity Assay

ACE2 activity was measured in brain and kidney removed from each group (n=4/per group), as described previously.23 Data (arbitrary fluorescence units [AFUs]) are presented as amounts of fluorogenic peptide substrate VI converted to product per minute and are normalized for total protein.

Western Blot

Mouse brain and kidneys were collected (n=4/per group) and processed using a standard Western blot protocol against rabbit-antimouse (m)ACE2, rabbit antihuman (h)ACE2, and rabbit polyclonal AT1R antibodies. Specific bands were detected by chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified by laser densitometry.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means±SEMs. Data were analyzed, when appropriate, by Student t test, repeated-measures ANOVA, or 1-way ANOVA (after Bartlett test of homogeneity of variance) followed by Tukey-Kramer correction for multiple comparisons between means. Statistical comparisons were performed using Prism5 (GraphPad Software). Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

Losartan Normalizes BP and Baroreflex Sensitivity in RA Mice

It was reported previously that RA mice have chronically elevated plasma Ang II levels and hypertension16 and that acute blockade of brain AT1R resulted in a dramatic decrease of BP,24 suggesting a major role for the brain RAS in this model. To determine whether AT1Rs are mediating the chronic hypertensive effects of Ang II in these mice, selective AT1R and AT2R antagonists, losartan and PD1233219, respectively, or vehicle, were infused SC in conscious RA mice for 2 weeks and compared with NT littermates. Typical BP recordings showing the BP level in the various groups after 2-week infusion are presented on Figure 1A, and daily BP is plotted on Figure 1B. Consistent with previously reported data,16,24 baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP) was significantly elevated in RA compared with NT mice (150±4 versus 104±1 mmHg; P<0.001; Figure 1B). Chronic infusion of losartan (2 weeks) caused a dramatic decrease in MAP in RA mice (ΔMAP: −43±6 mm Hg; P<0.05 versus baseline; Figure 1B), and normalized BP as early as 2 days after the beginning of infusion. Losartan also decreased MAP in NT, although the reduction was less pronounced than in RA mice (−9±5 mm Hg; P<0.05; Figure 1B). PD123319 infusion did not affect MAP in NT (ΔMAP: −0.3±2.7 mm Hg; P>0.05) or RA (ΔMAP: −0.6±3.5 mm Hg; P>0.05) compared with baseline (Figure 1B). Similarly, saline infusion did not change MAP in any group (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Losartan normalizes BP and SBRS in RA mice. A, Typical BP recording traces in conscious NT and RA mice. B, Baseline MAP was significantly higher in RA vs NT mice (n=12; ***P<0.001); chronic infusion of the selective AT1R antagonist losartan (10 mg/kg per day SC) normalized MAP in RA (n=12; ‡P<0.001 vs RA+saline) and slightly decreased MAP in NT mice (n=12; †P<0.05 vs NT+saline). The AT2R antagonist PD123319 (10 mg/kg per day SC) did not affect MAP in any strain (n=12; P>0.05 vs saline). C, Baseline SBRS was significantly lower in RA vs NT mice (n=12; ***P<0.001). Chronic infusion of losartan restored SBRS only in RA mice (‡P<0.001 vs RA+saline), whereas AT2R blockade did not affect SBRS in NT or RA mice.

The cardiac baroreceptor reflex is one of the major central regulatory mechanisms for BP, and we reported previously that SBRS is impaired in RA mice.25 To assess the involvement of central Ang II receptors, we determined SBRS after chronic infusion in mice. SBRS was significantly reduced in RA mice compared with NT littermates (0.80±0.06 versus 2.04±0.15 ms/mm Hg; P<0.001; Figure 1C), and both up and down sequences were affected (Figure S1). Saline and PD123319 did not alter SBRS in any group (Figure 1C). Although losartan infusion did not modify SBRS in NT mice (2.51±0.53 ms/mmHg; P>0.05 versus NT baseline; Figure 1C), it fully restored the baroreflex gain in transgenic littermates (1.69±0.31 ms/mm Hg; P<0.001 versus RA baseline; Figure 1C), increasing SBRS for both up and down sequences (Figure S1).

To determine whether BP dysregulation (ie, impaired SBRS and high BP) in RA mice is associated with upregulation of brain AT1R, immunostaining and Western blot analysis were performed for this receptor in both NT and RA mice brains. Representative AT1R immunostaining pictures of nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS) and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) for NT and RA mice are shown in Figure S2A. Quantification of immunoreactivity (relative density units [RDU]) shows that AT1R density is not different (P>0.05) in the NTS (1.05±0.01 versus 1.00±0.01 RDU) and RVLM (1.02±0.01 versus 1.00±0.01 RDU) of RA compared with NT mice, respectively (Figure S2B and S2C). Similarly, Western blotting shows a lack of difference in AT1R protein expression (P>0.05) in the dorsal (1.05±0.2 versus 1.0±0.10 RDU) and ventral (1.19±0.22 versus 1.0±0.10 RDU) medulla between RA and NT mice, respectively (Figure S2D and S2E), suggesting that BP dysregulation is not associated with AT1R upregulation in RA mice.

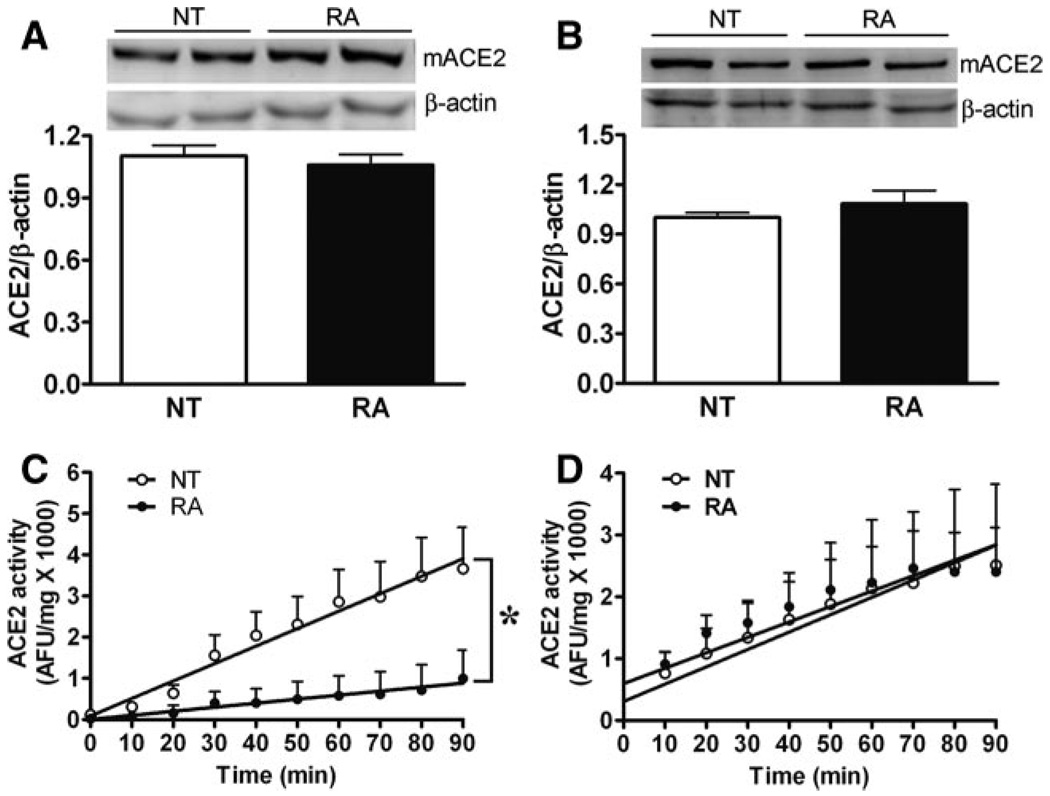

Decreased ACE2 Activity in the Brain of RA Mice

We previously identified ACE2 in RA mouse brain, and the enzyme expression has been reported to be decreased in hypertensive rats.26 To determine whether ACE2 is impaired in this hypertensive model, we measured ACE2 protein expression and activity in the brain and kidneys of RA and NT mice. Western blots show that ACE2 protein expression was not significantly different (P>0.05) in the brain (0.97±0.05 versus 1±0.02 RDU; Figure 2A) or kidney (1.01±0.08 versus 1±0.03 RDU; Figure 2B) of RA compared with NT mice, respectively. To further ascertain this observation, we also measured ACE2 activity in these tissues. Interestingly, we observed that ACE2 activity was significantly lower in the brain of RA compared with NT mice (16.6±7 versus 48.7±7 AFU/mg per minute; P<0.05; Figure 2C), whereas it was not altered in the kidney between these groups (28.1±9.5 versus 25.0±5.1 AFU/mg per minute; P>0.05; Figure 2D). These data suggest a possible relationship between impaired central ACE2 activity and hypertension.

Figure 2.

ACE2 expression and activity in RA mice. Western blotting showed no changes in mACE2 protein expression in the brain (A) or kidney (B) of RA vs NT mice (n=4; P>0.05). ACE2 activity was significantly decreased in the brain of RA (C) (n=4; *P<0.05) but not altered in the kidney (D; n=4; P>0.05) when compared with NT littermates.

Losartan Restores Brain ACE2 Activity in RA Mice

To address the participation of central Ang II receptors in the reduction of ACE2 activity in RA mice, we further investigated how ACE2 expression and activity were affected by ATR antagonists in the brain of these hypertensive mice. Western blot analysis shows that ACE2 protein expression in the brain of RA mice was not modified (P>0.05) by losartan or PD123319 treatments (Figure 3A). However, ACE2 activity was significantly increased after losartan infusion (26.4±1.8 versus 13.3±3.2 AFU/mg per minute; P<0.05; Figure 3B) and restored to the same level observed in NT mice brain (Figure 2C). PD123319 treatment did not affect brain ACE2 activity in these mice (Figure 3B). Furthermore ACE2 activity in the brain of NT mice was not modified by losartan (34.1±0.1 AFU/mg per minute) or PD123319 (27.8±0.2 AFU/mg per minute) infusion compared with saline infusion (33.4±0.2 AFU/mg per minute). These data suggest that AT1Rs exert an inhibitory influence over central ACE2 activity in RA mice.

Figure 3.

Effects of ATR blockade on ACE2 protein expression and activity in the brain of RA mice. A, Typical Western blot and quantified data showing that protein expression of mACE2 in the brain of RA mice was not affected by losartan or PD123319 (10 mg/kg per day sc, 14 days; n=4; P>0.05 vs RA). B, ACE2 activity in the brain of RA mice was significantly increased after AT1R blockade (n=4; *P<0.05 vs RA) but not altered by the AT2R antagonist PD123319 (n=4; P>0.05 vs RA).

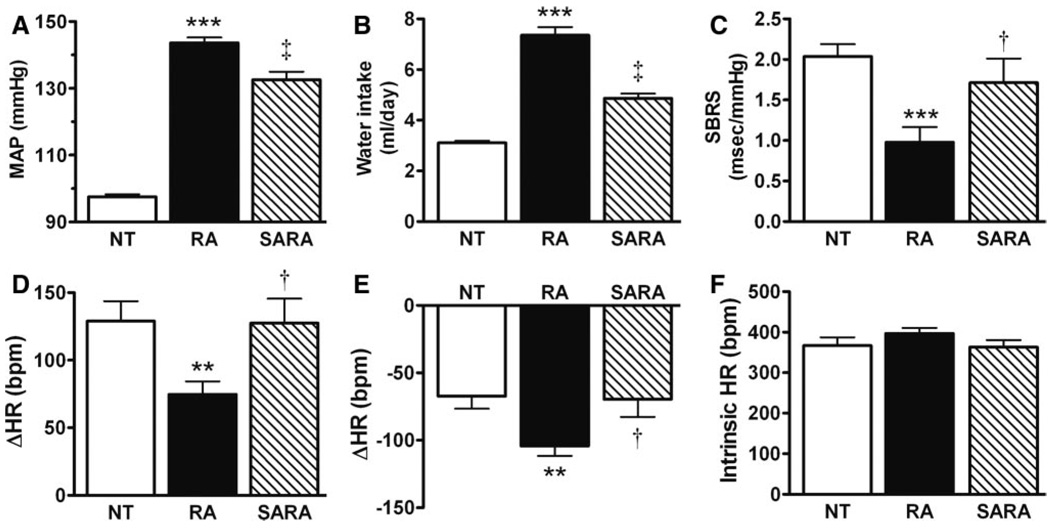

Central Overexpression of ACE2 Decreases BP in Hypertensive Mice

To test the hypothesis that ACE2 overexpression may reduce BP in chronically hypertensive mice, we monitored BP in triple-transgenic SARA mice in a conscious freely moving state for 6 days. The SARA mouse is a triple-transgenic model with widespread overexpression of renin and angiotensinogen and ACE2 selectively in the brain (an expanded Results section describing this model is available in the online data supplement). As observed previously, MAP is significantly higher in RA (144±2 mmHg; P<0.001) compared with NT (97±0.8 mm Hg) mice. Interestingly, MAP is significantly lower in SARA (133±2 mmHg; P<0.01) compared with the chronically hypertensive mice (Figure 4A), suggesting that ACE2 overexpression in the CNS can modulate the central regulation of BP. To confirm the ability of ACE2 expression to counter chronic Ang II-mediated responses, the drinking behavior was assessed among the various strains. A dramatic increase in daily water intake was observed in RA (7.4±0.3 mL; P<0.001) compared with NT (3.1 ±0.1 mL) mice, as a result of elevated Ang II levels in this model. As observed above for BP, overexpression of ACE2 in the brain blunted the enhanced water intake in hypertensive mice (SARA: 4.9±0.2 mL; P<0.01 versus RA; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

ACE2 overexpression attenuates Ang II-mediated responses in SARA mice. The dramatic BP (A) and water intake (B) increases observed in RA (n=12; ***P<0.001 vs NT) were significantly attenuated in SARA mice (n=12; ‡P<0.01 vs RA). Moreover, the impaired SBRS (C), reduced parasympathetic tone (D), and enhanced sympathetic drive (E) observed in RA (n=12; ***P<0.001 and **P<0.01 vs NT) were fully normalized by ACE2 overexpression in the brain (n=12; †P<0.05 vs RA). Intrinsic heart rate (F) shows no difference between genotypes (n=12; P>0.05).

To address whether the MAP reduction in SARA mice is supported by modification in the central mechanisms regulating BP, baroreflex and autonomic function were investigated in this triple-transgenic mouse. Surprisingly, the impaired SBRS observed in RA mice (0.98±0.19 ms/mmHg) was restored by overexpression of ACE2 in the brain (SARA 1.71±0.30 ms/mm Hg; P<0.05 versus RA; Figure 4C) to the level observed in NT mice (2.04±0.15 ms/mmHg).

In addition, the decreased parasympathetic (ΔHR: +75±10 bpm; Figure 4D) and increased sympathetic (ΔHR: − 104±7 bpm; Figure 4E) tones observed in RA compared with NT mice (+129±15 and −67±9 bpm, respectively; P<0.01) were totally restored in SARA mice (atropine: +128±18; propranolol: −70±13 bpm; Figure 4D and 4E; P<0.05 versus RA). Baseline HR was not different among the 3 strains (NT: 529±10 bpm; RA: 540±10 bpm; and SARA: 532±14 bpm). After ganglionic blockade, MAP was dramatically decreased in all of the groups (NT: 69±2; RA: 83±5; and SARA: 71±3 mm Hg) but remained higher in RA mice, whereas it was not different between SARA and NT mice. There was no difference in intrinsic HR among the different genotypes (Figure 4F). Taken together, these data suggest that overexpression of ACE2 in the brain prevents the Ang II-mediated impairments of baroreflex and autonomic function observed in chronically hypertensive mice.

Discussion

ACE2 is a carboxypeptidase capable of transforming Ang II into the vasodilator peptide Ang-(1–7), thus it is in a position to modulate RAS overactivity. Previous studies have shown that AT1R blockade increases cardiac ACE2 expression and activity.15 However, the role of brain ACE2 in the central regulation of BP and the consequences of its interaction with other RAS components are unknown. The present study demonstrates that brain ACE2 activity is inhibited by AT1R in chronically hypertensive mice and is associated with impaired baroreflex function. Using genetic complementation, we show that ACE2 overexpression in the CNS normalizes baroreflex and autonomic function, thus contributing to the reduction of hypertension.

The baroreflex is a key mechanism that permits the fine tuning of the autonomic nervous system activity to the heart, kidney, and vessels to maintain BP homeostasis. Central and circulating Ang II levels are known to inhibit baroreflex sensitivity, and these effects are mediated by AT1R located in the NTS and RVLM.27 Hypertensive models, such as spontaneously hypertensive rats and transgenic rats carrying mouse Ren-2d renin gene [TGR(mRen2)], exhibit high brain Ang II levels and increased AT1R expression,28,29 and enhanced AT1R stimulation in the NTS and RVLM results in blunted baroreflex sensitivity.27,30 Unlike these hypertensive models, RA mice do not appear to have upregulation of AT1R in the brain. However, the fact that circulating Ang II can lead to an increase in brain Ang II levels31 and the presence of both hAGT and hRen transgenes in the CNS24 suggest that Ang II is elevated in the brain. Our data show that there is no difference in brain stem AT1R expression between RA and controls, suggesting that impaired SBRS and BP dysregulation are not associated with AT1R upregulation in RA mice but more likely attributed to high Ang II levels16 that would lead to increased stimulation of these receptors. Hence, the involvement of AT1R was confirmed by the restoration of baroreflex sensitivity in RA mice after losartan infusion. Although AT2Rs have been identified in brain stem nuclei involved in BP regulation, such as the locus coeruleus, lateral septum, and the medial amygdala,10 and there is evidence that AT2Rs contribute to baroreflex regulation,32 our data show that these receptors do not participate in the baroreflex function and BP regulation in RA mice.

ACE2 is thought to be a putative candidate gene for hypertension.26 Accumulating evidence shows downregulation of ACE2 in both the heart and kidney of several hypertensive animal models and patients with hypertension,33 suggesting the involvement of peripheral ACE2 in BP regulation. However, very few studies have investigated the interaction of central ACE2 expression/activity and BP regulation. It has been shown that ACE2 expression was reduced by 40% in the RVLM of spontaneously hypertensive rats compared to normotensive Wistar-Kyoto rats,34 but the link between reduced ACE2 expression and impaired baroreflex sensitivity has not been investigated. There is evidence of interactions between AT1R and ACE2 in peripheral organs. In animals treated with AT1R blockers, ACE2 expression and/or activity was increased in the heart, kidney, thoracic aorta, and carotid artery.33 Unlike other hypertensive models,26,35 RA mice do not exhibit decreased ACE2 expression or activity in kidneys (and heart; data not shown). Interestingly, whereas ACE2 expression was not altered in the brain of these mice, the activity of the enzyme was significantly reduced. Accordingly, one could imagine that downregulation of ACE2 might depend on the level of AT1R in the brain. Although this is speculative, we recently demonstrated a similar relationship between these 2 RAS components, where ACE2 overexpression in the subfornical organ resulted in downregulation of AT1R in this region,36 suggesting that the carboxypeptidase can affect AT1R transcription and/or internalization.

Impaired central ACE2 activity is concomitant with reduced baroreflex gain and hypertension in RA mice, suggesting a role for ACE2 in the maintenance of baroreflex function, necessary to preserve BP homeostasis. These observations are consistent with a recent study showing that pharmacological inhibition of ACE2 activity by MLN4760 in the NTS attenuates the reflex bradycardia in normotensive and anesthetized rats.14 Moreover, data from our laboratory show that ACE2 knockout mice have impaired baroreflex and autonomic function, supporting the idea that ACE2 is critical to maintain a normal baroreflex function.33 We furthered these observations by showing not only that AT1R (but not AT2R) blockade restores baroreflex sensitivity but also that genetic complementation, leading to ACE2 overexpression in the brain, normalizes baroreflex function in conscious and chronically hypertensive mice. Altogether, our data suggest that impaired baroreflex sensitivity is secondary to the inhibition of ACE2 activity by AT1R. However, although this effect can be reversed by losartan, it remains a possibility that AT1Rs are not directly mediating ACE2 inhibition. It is conceivable that it might indirectly alter neurotransmitters levels, which would eventually have a feedback effect on ACE2 activity. Furthermore, although losartan did not affect ACE2 activity at the periphery, it is possible that peripheral AT1R blockade may have contributed to the restoration of baroreflex sensitivity.

The major role of ACE2 consists of cleaving Ang II into Ang-(1–7).6 Accordingly, inhibition of brain ACE2 activity in RA mice could reduce Ang II degradation and Ang-(1–7) production, thus promoting AT1R-mediated baroreflex dysfunction and hypertension. Recently, we showed that, although the reduction of Ang II is significant, the formation of Ang-(1–7) is the major pathway involved in BP regulation, after chronic ACE2 overexpression in the mouse brain.17 However, whereas central administration of Ang-(1–7) has been shown to increase cardiac baroreflex sensitivity,11 it is not known whether binding of the Ang-(1–7) receptor leads to activation of its own signaling cascades or to inhibition of the AT1R downstream signaling.

Using virus-mediated gene targeting, our laboratory and others have recently provided evidence of a role for brain ACE2 in the central regulation of BP. Yamazato et al34 showed that lentivirus-mediated ACE2 overexpression targeted to the RVLM resulted in the reduction of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Using an adenovirus coding for ACE2, we showed that ACE2 overexpression in the subfornical organ prevented the Ang II–mediated pressor and drinking responses.36 Although these studies provide the first evidence for the beneficial effects of ACE2 overexpression in the CNS, long-term and high-level expression is needed to dissect the mechanism(s) of action and the regulation of this enzyme in the brain. Transgenic models have the advantage of providing stable and chronic expression of target genes. By using SARA mice, a triple-transgenic model with overexpression of ACE2, renin, and angiotensinogen in the brain, we confirmed that impaired brain ACE2 activity results in baroreflex dysfunction and BP dysregulation in hypertensive mice. Interestingly, ACE2 overexpression in the brain did not fully reduce BP in this model, although it normalized baroreflex and autonomic function. Although RA mice present high Ang II levels throughout their body, the resulting hypertension has been shown to exhibit a strong neurogenic component that could temporarily be reduced by acute blockade of brain AT1R.24 Therefore, although central ACE2 overexpression could modulate baroreflex and autonomic function, it is unlikely to correct the peripheral mechanisms affected by chronic exposure to high Ang II levels. In addition, although the drinking response was attenuated in SARA mice, indicating less Ang II in the brain, the residual enhanced water intake suggests that Ang II levels are not normalized in this model.

Perspectives

The discovery of ACE2 has allowed a filling of the gap between Ang II and Ang-(1–7). We now show evidence of the following: (1) AT1Rs inhibit ACE2 activity but not expression in the brain of hypertensive mice; (2) AT2Rs do not modulate central ACE2 expression and/or activity; (3) brain ACE2 plays a critical role in the baroreflex function homeostasis and, consequently, in the prevention of hypertension; and (4) the beneficial effects of AT1R blockade on BP regulation and baroreflex function are mediated, at least partially, by an increase in ACE2 activity. Essentially, we have established the importance of central ACE2 in the preservation of baroreflex and autonomic function and its potential in the reduction of hypertension, thus confirming ACE2 as a potential target for the treatment of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants NS052479, RR018766, and HL093178.

Footnotes

Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at http://www.lww.com/reprints

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Paul M, Poyan Mehr A, Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin-angiotensin systems. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Bohlen und Halbach O, Albrecht D. The CNS renin-angiotensin system. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:599–616. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey RM, Padia SH. Angiotensin AT2 receptors: control of renal sodium excretion and blood pressure. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao L, Wang W, Wang W, Li H, Sumners C, Zucker IH. Effects of angiotensin type 2 receptor overexpression in the rostral ventrolateral medulla on blood pressure and urine excretion in normal Rats. Hypertension. 2008;51:521–527. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazartigues E, Feng Y, Lavoie JL. The two fACEs of the tissue renin-angiotensin systems: implication in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:1231–1245. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, Godbout K, Parsons T, Baronas E, Hsieh F, Acton S, Patane M, Nichols A, Tummino P. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14838–14843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos RAS, Silva ACS, Maric C, Silva DMR, Machado RP, de Buhr I, Heringer-Walther S, Pinheiro SV, Lopes MT, Bader M, Mendes EP, Lemos VS, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Schultheiss HP, Speth R, Walther T. Angiotensin-(1–7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapleau MW, Abboud FM. Neuro-cardiovascular regulation: from molecules to man. Introduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:xiii–xxii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao L, Wang W, Li YL, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Sympathoexcitation by central Ang II: roles for AT1 receptor upregulation and NAD(P)H oxidase in the RVLM. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2271–H2279. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00949.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenkei Z, Palkovits M, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. Expression of angiotensin type-1 (AT1) and type-2 (AT2) receptor mRNAs in the adult rat brain: a functional neuroanatomical review. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1997;18:383–439. doi: 10.1006/frne.1997.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campagnole-Santos MJ, Heringer SB, Batista EN, Khosla MC, Santos RA. Differential baroreceptor reflex modulation by centrally infused angiotensin peptides. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:R89–R94. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.1.R89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakima A, Averill DB, Gallagher PE, Kasper SO, Tommasi EN, Ferrario CM, Diz DI. Impaired heart rate baroreflex in older rats: role of endogenous angiotensin-(1–7) at the nucleus tractus solitarii. Hypertension. 2005;46:333–340. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000178157.70142.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doobay MF, Talman LS, Obr TD, Tian X, Davisson RL, Lazartigues E. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with over-expression of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R373–R381. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00292.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diz DI, Garcia-Espinosa MA, Gegick S, Tommasi EN, Ferrario CM, Ann Tallant E, Chappell MC, Gallagher PE. Injections of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitor MLN4760 into nucleus tractus solitarii reduce baroreceptor reflex sensitivity for heart rate control in rats. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:694–700. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, Diz DI, Gallagher PE. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605–2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merrill DC, Thompson MW, Carney CL, Granwehr BP, Schlager G, Robillard J, Sigmund CD. Chronic hypertension and altered baroreflex responses in transgenic mice containing the human renin and human angiotensinogen genes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1047–1055. doi: 10.1172/JCI118497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Y, Halabi CM, Sigmund CD, Lazartigues E. Brain-selective over-expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 prevents Ang II-mediated pressor effects in transgenic mice. Hypertension. 2007;50:e83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butz GM, Davisson RL. Long-term telemetric measurement of cardiovascular parameters in awake mice: a physiological genomics tool. Physiol Genomics. 2001;5:89–97. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.5.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parati G, Di Rienzo M, Bertinieri G, Pomidossi G, Casadei R, Groppelli A, Pedotti A, Zanchetti A, Mancia G. Evaluation of the baroreceptor-heart rate reflex by 24-hour intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring in humans. Hypertension. 1988;12:214–222. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.12.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stauss HM, Moffitt JA, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM, Johnson AK. Baroreceptor reflex sensitivity estimated by the sequence technique is reliable in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H482–H483. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00228.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.do Carmo JM, Hall JE, da Silva AA. Chronic central leptin infusion restores cardiac sympathetic-vagal balance and baroreflex sensitivity in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1974–H1981. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazartigues E, Sinnayah P, Augoyard G, Gharib C, Johnson AK, Davisson RL. Enhanced water and salt intake in transgenic mice with brain-restricted overexpression of angiotensin (AT1) receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1539–R1545. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00751.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huentelman MJ, Zubcevic J, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK. Cloning and characterization of a secreted form of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Regul Pept. 2004;122:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davisson RL, Yang GY, Beltz TG, Cassell MD, Johnson AK, Sigmund CD. The brain renin-angiotensin system contributes to the hypertension in mice containing both the human renin and human angiotensinogen transgenes. Circ Res. 1998;83:1047–1058. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.10.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazartigues E, Whiteis CA, Maheshwari N, Abboud FM, Stauss HM, Davisson RL, Chapleau MW. Oxidative stress contributes to increased sympathetic vasomotor tone and decreased baroreflex sensitivity in hypertensive and hypercholesterolemic mice. FASEB J. 2004;18:A299. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y, Scholey J, Ferrario CM, Manoukian AS, Chappell MC, Backx PH, Yagil Y, Penninger J. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–828. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumura K, Averill DB, Ferrario CM. Angiotensin II acts at AT1 receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract to attenuate the baroreceptor reflex. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1611–R1619. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.5.R1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutkind JS, Kurihara M, Castren E, Saavedra JM. Increased concentration of angiotensin II binding sites in selected brain areas of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 1988;6:79–84. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morishita R, Higaki J, Nakamura Y, Aoki M, Yamada K, Moriguchi A, Rakugi H, Tomita N, Tomita S, Yu H. Effect of an antihypertensive drug on brain angiotensin II levels in renal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22:665–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diz DI, Jessup JA, Westwood BM, Bosch SM, Vinsant S, Gallagher PE, Averill DB. Angiotensin peptides as neurotransmitters/neuromodulators in the dorsomedial medulla. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:473–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazartigues E, Lawrence AJ, Lamb FS, Davisson RL. Renovascular hypertension in mice with brain-selective overexpression of AT1a receptors is buffered by increased nitric oxide production in the periphery. Circ Res. 2004;95:523–531. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000140892.86313.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luoh HF, Chan SHH. Participation of AT1 and AT2 receptor subtypes in the tonic inhibitory modulation of baroreceptor reflex response by endogenous angiotensins at the nucleus tractus solitarii in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;782:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia H, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in the brain: properties and future directions. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1482–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamazato M, Yamazato Y, Sun C, Diez-Freire C, Raizada MK. Overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the rostral ventrolateral medulla causes long-term decrease in blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2007;49:926–931. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000259942.38108.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhong JC, Huang DY, Yang YM, Li YF, Liu GF, Song XH, Du K. Upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by all-trans retinoic acid in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2004;44:907–912. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000146400.57221.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng Y, Yue X, Xia H, Bindom SM, Hickman PJ, Filipeanu CM, Wu G, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression in the subfornical organ prevents the angiotensin II-mediated pressor and drinking responses and is associated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor downregulation. Circ Res. 2008;102:729–736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.169110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.