Abstract

Acne vulgaris affects up to 80% of people 11 to 30 years of age, and scarring can occur for up to 95% of these patients. Scarring may be pitted or hypertrophic in nature, although in most cases it is atrophic. Atrophic acne scarring follows dermal collagen and fat loss after moderate to severe acne infection. Injectable poly-L-acid (PLLA) is a biocompatible, biodegradable, synthetic polymer device that is hypothesized to enhance dermal volume via the endogenous production of fibroblasts and, subsequently, collagen. The gradual improvements in cutaneous volume observed after treatment with injectable PLLA have been noted to last up to 2 years. The case studies presented describe the use of injectable PLLA to correct dermal fat loss in macular atrophic acne scarring of the cheeks. Two female patients underwent three treatment sessions with injectable PLLA over a 12-week period. At each treatment session, the reconstituted product was injected into the deep dermis under the depressed portion of the scar. Both patients were extremely pleased with their results at, respectively, 1- and 4-year follow-up evaluations. Patients experienced minimal swelling and redness after injection and no product-related adverse events such as papule and/or nodule formation. The author believes these data suggest that injectable PLLA is a good treatment option for the correction of macular atropic scarring with thin dermis (off-label use), particularly compared with other injectable fillers currently used for this indication that have shorter durations of effect.

Keywords: Acne, Lipoatrophy, Poly-l-lactic acid, Scarring

Acne vulgaris is the most common of all skin diseases, and although it can occur at any age, it affects up to 80% of people ranging in age from 11 to 30 years [12]. Furthermore, infectious acne leads to sequelae that include scarring and various forms of contour abnormalities [3]. In fact, scarring can occur in up to 95% of acne patients [14]. The scarring may be pitted “atrophic,” macular “atrophic,” or hypertrophic in nature [6, 8, 10], and it has a negative impact on patient self-esteem and quality of life [5, 15].

To correct the signs of acne scarring, a number of different treatments have been used such as dermabrasion, laser resurfacing, skin grafting, punch excisions, chemical peels, subcision, and injectable agents. However, because scarring can vary considerably in depth and type, different techniques often are applied simultaneously or in series, according to the type of scar, to achieve an adequate treatment effect [1, 3, 9, 22].

This article focuses on the treatment of macular atrophic scars, such as boxcar scars. Macular atrophic scars are broad in nature, create less stark shadows, and are easier to conceal with makeup than small and deep ice-pick scars. The concept of using injectable agents such as collagen, hyaluronic acid, and silicone to fill this type of scarring has long been established [2, 11, 13]. In the two reported case studies, injectable poly-L-acid (PLLA; Sculptra; Dermik Laboratories, a division of Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) was used to correct dermal fat loss associated with macular atrophic scarring after severe chronic acne.

Injectable PLLA is a biocompatible, biodegradable, synthetic polymer widely used throughout Europe, the United States, and several other countries for restoration or correction of lipoatrophy signs in people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [16, 17, 21]. Injectable PLLA also is approved in Europe, Brazil, Australia, and Canada for the cosmetic correction of facial volume defects. It currently is under review by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States for volume restoration or correction of facial wrinkles and folds such as nasolabial lines or folds.

After injection, PLLA is thought to elicit the endogenous production of fibroblasts and, subsequently, collagen, thereby enhancing tissue volume gradually over time [7, 19]. Significant increases in dermal volume have been observed after administration of injectable PLLA, with results observed to last up to 2 years and potentially longer in certain instances [4, 16–18, 22].

Although injectable PLLA is not appropriate for treating all varieties of acne scarring, it can be used effectively to replace lost dermal volume in depressed scars (i.e., those caused by loss of lower dermis or subcutaneous fat), such as macular atrophic scars [3]. Recently, injectable PLLA has been used successfully to correct this type of scarring after either severe acne or varicella (chicken-pox) virus infection, demonstrating significant reductions in acne scar size and severity [3].

The author, with considerable experience using injectable PLLA for the effective correction of depressed facial acne scarring, presents two case studies describing such treatment. The use of injectable PLLA for active acne, hypotrophic, keloid, or ice-pick scarring is not advocated. It should be noted that injectable PLLA is not currently indicated for the correction of acne scaring in the United States, and that this article describes off-label use of the agent for this purpose. Additionally, the reconstitution and administration practices detailed may not reflect the manufacturer’s current recommendations for the use of injectable PLLA [20].

Materials and Methods

Case Studies

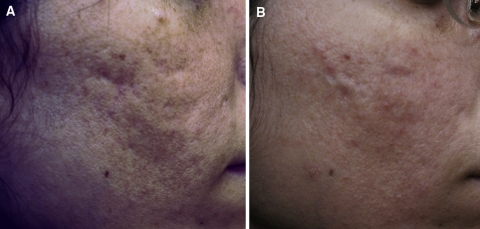

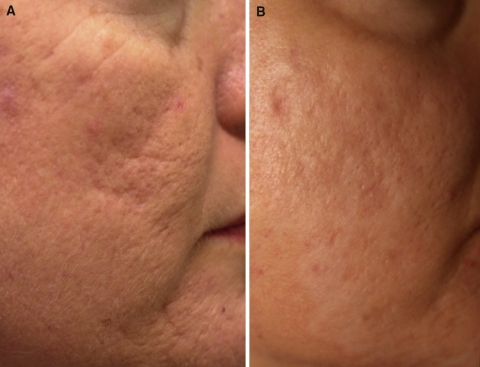

Injectable PLLA was used to treat two women, ages 21 (Fig. 1) and 45 years (Fig. 2), with dermal fat atrophy caused by chronic and severe facial acne of the cheeks. Both patients, in good health with no comorbid diseases or infections, signed consent forms before treatment.

Fig. 1.

Case study 1. Photographs before (a) and 1 year after (b) the final treatment of a 21-year-old patient who underwent three injectable poly-l-lactic acid treatment (dermal lipoatrophy) sessions for facial “scarring” caused by chronic acne

Fig. 2.

Case study 2. Photographs before (a) and 4 years after (b) the final treatment of a 45-year-old patient who underwent three poly-l-lactic acid treatment (dermal lipoatrophy) sessions for facial “scarring” caused by chronic acne

The 45-year-old patient received one carbon dioxide (CO2) laser peel 6 months before her PLLA injections. Pretreatment consultation included the rationale for using injectable PLLA, as opposed to collagen, hyaluronic acid, or silicone fillers. The considerable volume enhancement elicited with injectable PLLA was described, as well as the potential longevity of the results.

The patients also were advised that after injection with PLLA, increases in dermal volume would occur gradually over time due to the hypothesized mode of operation. A few weeks would be required until the first signs of improvement. It was explained to the patients that after PLLA injection, they might experience transient injection-related adverse effects such as swelling, redness, and possibly bruising, and that these effects would most likely resolve spontaneously.

Treatment

Each patient underwent three treatment sessions with injectable PLLA spaced 6 weeks apart. For injection at every treatment, the product was reconstituted with 5 ml of sterile water and allowed to stand for 24 h before injection. All areas on the cheeks to be treated were first cleansed with alcohol and then injected with anesthetic (1% lidocaine epinephrine administered with a 30-gauge needle).

At each treatment session, injectable PLLA was administered into the deep dermis with a 23-gauge 2-in. needle. In the author’s opinion, a 23-gauge needle results in lower injection resistance than the manufacturer-recommended 26-gauge needle [20] and therefore can afford more controlled injection of material. Furthermore, as the anesthetic is administered by the author before treatment, the increased needle size does not result in increased patient discomfort.

With the needle positioned under the depressed portion of the scar, PLLA was placed at the dermal/subcutaneous tissue junction using a layering technique. A small amount of material (1 ml), dispersed throughout the skin, was injected under low pressure with this method, using an active motion of the needle to avoid “lakeing” of injectable PLLA beneath the skin. The material was deposited under the dermis because the epidermis and dermis of the acne scar tissue was very thin.

Injections to specific scars were complete when the level of the treated area was raised to that of the surrounding skin. Altogether, 2 ml of injectable PLLA per cheek was deposited under the surface of the dermis for a total volume of 4 ml per treatment session.

No massage was performed after injection for acne scaring, and patients were discouraged from performing this action. It is important to note that during correction of age- or HIV-associated lipoatrophy with injectable PLLA, massage is regularly used to ensure an even distribution of the product. However, with the layering procedure used for these patients, the author believes that adequate and even distribution of the material can be achieved through the use of correct injection technique.

Results

The patients experienced minimal swelling and redness for 24 to 48 h after injection. No product-related adverse events, such as papule or nodule formation, were noted at the 3-year follow-up evaluation for the 21-year-old or at the 6-year follow-up evaluation for the 45-year-old. After 1 year of treatment with injectable PLLA for the 21-year-old (Fig. 1b) and 4 years of treatment for the 45-year-old (Fig. 2b), the author determined the results to be excellent, as assessed using photographs and physical examination. Furthermore, each patient was extremely pleased with the results, and specifically, the improvement in the contour and color of the treated areas. Fewer shadows in the skin were apparent. The case studies suggest that injectable PLLA is a good treatment option for the correction of dermal fat atrophy after severe acne.

Discussion

The severity and morphology of acne scarring often is linked to the intensity of the disease, and in most cases scarring is atrophic [14]. Like all scars, acne scars are visible due to their color and the shadows they create in the skin. The morphology of an atrophic scar is influenced by the loss of collagen and sometimes the loss of subcutaneous fat (lipoatrophy) that results from acne infection. After mild acne, soft papular and rolling (gently undulating) scars can develop, whereas after moderate disease, hypertrophic/papular and rolling scars are more prominent. Boxcar scars that are polygonal and terminate in the shallow-to-mid dermis also may develop with moderate acne. Severe acne can lead to gross atrophy, dystrophic scars, significant hypertrophy, and/or keloids. Ice-pick scars, which are round, deep, pitted, and tapered into the dermis, also can appear, along with deep boxcar scars that terminate in the reticular dermis. The destruction and dissolution of the lower dermis and the lipoatrophy that characterizes these atrophic scars usually occur at the time of chronic or active disease.

Previous methods for treating acne scarring have involved applying a number of treatments. For example, Whang and Lee (1999) developed an effective three-step therapeutic approach to treat various types of acne scaring [23]. Initially, focal chemical peeling (with 50% trichloroacetic acid) was undertaken to form new granulation tissue [23]. This was followed by CO2 laserbrasion (for pitted scars), excision (for large linear and isolated scars in skin creases), or punch grafting/elevations (for ice-pick scars) [23]. Dermabrasion used to be the final step for resurfacing any remaining irregularities [23].

The reported cases demonstrate the use of a single injectable agent for successful treatment of fat atrophy secondary to severe acne. Injectable PLLA is a biocompatible, biodegradable, synthetic polymer hypothesized to elicit the endogenous production of fibroblasts and, subsequently, collagen. Currently, little information on the use of injectable PLLA for the treatment of macular dermal atrophy after severe acne is available. However, the reported case studies indicate that injectable PLLA is a good treatment option for the correction of dermal fat atrophy after severe acne. The author believes that correction for this type of scarring with injectable PLLA is elicited by filling of the scar as collagen is replaced, and that this volume enhancement may be more substantial and durable than that resulting from the use of other dermal injectable agents.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Karen Phelps, PhD, Medicus International, for her editorial support. Editorial support for this article was provided by Dermik Laboratories, a division of Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC. The opinions expressed in the article are those of the author.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Alam M, Omura N, Kaminer MS (2005) Subcision for acne scarring: technique and outcomes in 40 patients. Dermatol Surg 31:310–317 (discussion 317) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Barnett JG, Barnett CR (2005) Treatment of acne scars with liquid silicone injections: 30-year perspective. Dermatol Surg 31:1542–1549 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Beer K (2007) A single-center, open-label study on the use of injectable poly-l-lactic acid for the treatment of moderate to severe scarring from acne or varicella. Dermatol Surg 33(Suppl 2):S159–S167 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Burgess CM, Quiroga RM (2005) Assessment of the safety and efficacy of poly-l-lactic acid for the treatment of HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol 52:233–239 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ (1997) Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol 137:246–250 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Federman DG, Kirsner RS (2000) Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis and therapeutic approach. Am J Manag Care 6:78–87 (quiz 88–79) [PubMed]

- 7.Gogolewski S, Jovanovic M, Perren SM, Dillon JG, Hughes MK (1993) Tissue response and in vivo degradation of selected polyhydroxyacids: polylactides (PLA), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHB/VA). J Biomed Mater Res 27:1135–1148 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Goodman GJ, Baron JA (2007) The management of postacne scarring. Dermatol Surg 33:1175–1188 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Horton CE, Sadove RC (1987) Refinements in combined chemical peel and simultaneous abrasion of the face. Ann Plast Surg 19:504–511 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Jemec GB, Jemec B (2004) Acne: treatment of scars. Clin Dermatol 22:434–438 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Klein AW, Rish DC (1985) Substances for soft tissue augmentation: collagen and silicone. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 11:337–339 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kraning KK, OG (1979) Prevalence, morbidity, and cost of dermatologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol 73: S395–S401

- 13.Langdon RC (1999) Regarding dermabrasion for acne scars. Dermatol Surg 25:919–920 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Layton AM, Henderson CA, Cunliffe WJ (1994) A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol 19:303–308 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Loney T, Standage M, Lewis S (2008) Not just “skin deep”: psychosocial effects of dermatological-related social anxiety in a sample of acne patients. J Health Psychol 13:47–54 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mest DR, Humble G (2006) Safety and efficacy of poly-l-lactic acid injections in persons with HIV-associated lipoatrophy: The U.S. experience. Dermatol Surg 32:1336–1345 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Moyle GJ, Brown S, Lysakova L, Barton SE (2006) Long-term safety and efficacy of poly-l-lactic acid in the treatment of HIV-related facial lipoatrophy. HIV Med 7:181–185 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Moyle GJ, Lysakova L, Brown S, Sibtain N, Healy J, Priest C, Mandalia S, Barton SE (2004) A randomized open-label study of immediate versus delayed polylactic acid injections for the cosmetic management of facial lipoatrophy in persons with HIV infection. HIV Med 5:82–87 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Pistner H, Gutwald R, Ordung R, Reuther J, Muhling J (1993) Poly(l-lactide): along-term degradation study in vivo: I. Biological results. Biomaterials 14:671–677 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Sculptra® Product Information, Sanofi-Aventis 2006 Retrieved June 2008 at http://products.sanofi-aventis.us/sculptra/sculptra.html

- 21.Valantin MA, Aubron-Olivier C, Ghosn J, Laglenne E, Pauchard M, Schoen H, Bousquet R, Katz P, Costagliola D, Katlama C (2003) Polylactic acid implants (new-fill) to correct facial lipoatrophy in HIV-infected patients: results of the open-label study VEGA. AIDS 17:2471–2477 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Vleggaar D (2006) Soft-tissue augmentation and the role of poly-l-lactic acid. Plast Reconstr Surg 118:S46S–S54 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Whang KK, Lee M (1999) The principle of a three-staged operation in the surgery of acne scars. J Am Acad Dermatol 40:95–97 [DOI] [PubMed]