Abstract

The incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) varies widely according to age at diagnosis, geographic location, and ethnic background. On a global scale, NPC incidence is common among specific populations primarily living in southern and eastern Asia and northern Africa, but in most areas, including almost all western countries, it remains a relatively uncommon malignancy. Specific to these low-risk populations is a general observation of possible bimodality in the observed age-incidence curves. We have developed a multiplicative frailty model that allows for the demonstrated points of inflection at ages 15–24 and 65–74. The bimodal frailty model has 2 independent compound Poisson-distributed frailties and gives a significant improvement in fit over a unimodal frailty model. Applying the model to population-based cancer registry data worldwide, 2 biologically relevant estimates are derived, namely the proportion of susceptible individuals and the number of genetic and epigenetic events required for the tumor to develop. The results are critically compared and discussed in the context of existing knowledge of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of NPC.

Keywords: Carcinogenesis, Compound Poisson, Frailty, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Survival analysis

1. INTRODUCTION

There are remarkable and well-defined geographical and ethnic variations in the incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) worldwide. Rates are high to intermediate in certain areas of south-eastern China, southern Asia, northern Africa, and among Inuit populations of the Arctic region. With the exception of migrant populations from high-risk areas, rates of this malignancy tend to be uniformly low elsewhere. The aetiology of NPC is rather complex with causal pathways involving the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) as well as factors related to both the environment (often lifestyle related) and the host (genetic susceptibility) (Chang and Adami, 2006), (Hildesheim and Levine, 1993).

Age-incidence curves of certain cancers often exhibit a single peak in rates followed by a subsequent decline. Among alternative explanations, this unimodality may be interpreted as a frailty phenomenon, whereby most individuals are nonsusceptible to the disease, but a subset of individuals has an increased risk at a given age. The risk at the population level must decline once those susceptible individuals have acquired the disease, leaving the general population (at a given age) that is, in theory, nonsusceptible.

Frailty modeling provides an opportunity to take individual heterogeneity in disease susceptibility into account. For reviews of frailty theory, see for example the introductions by Aalen (1988), Aalen (1994) or Hougaard (2000). Frailty is an unobservable quantity modeled as a random variable over the population of individuals, with a high (low) value of the frailty variable associated with a large (small) risk of acquiring the disease. If the frailty variable is 0, the individual is nonsusceptible or `immune'.

The age-incidence curve of NPC for low-risk countries is somewhat atypical amongst cancer types. In Bray and others (2008), it was shown that for most, if not all populations in this category, rates exhibit a small peak within the age range 15–24, with rates steadily increasing to a second peak at ages 65–74 years, and then declining subsequently. The aims of this study were firstly to identify a frailty model that provides an adequate fit to this more complex instance of bimodality in the age-incidence structure, secondly to assess the significance of the first peak, and thirdly to interpret the resulting parameter estimates in the context of the current epidemiologic and biological knowledge of NPC.

Using a number of published data sets from population-based cancer registries worldwide, we include 2 frailties, one per peak, and 2 basic rates in the multiplicative frailty model. The frailties are assumed independent and compound Poisson distributed. This distribution has a discrete part of 0 frailty (i.e. nonsusceptible) and a continuous part of positive frailties. Covariates are included in the underlying Poisson parameters. We present the NPC hazard ratios by sex and geographical area in the analysis, together with 95% confidence intervals for these ratios. The observed and estimated age-specific incidence rates are plotted, and we examine the fit of the bimodal frailty model. Estimates of the proportion of susceptible individuals and the number of genetic and epigenetic events required to attain malignancy are given, with 95% confidence intervals.

This paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, the data sources and the model are described, together with some theoretical results. Section 3 presents the main results following application of the model to the data. Finally, in Section 4, the assumptions of the model are stated, and the results are discussed in light of our present understanding of the biology and aetiology of NPC.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Material

The Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) Vol. I to VIII ADDS database (Parkin and others, 2005) was used to extract incident cases of nasopharyngeal cancer (ICD-10 C11) for 72 population-based cancer registries, together with the corresponding population data by year of diagnosis, sex, and age. Although all nasopharyngeal cancers were extracted, rather than only NPCs, the term NPC is used here to identify carcinomas, given that they represent the vast majority of nasopharyngeal tumors, and the subset for which most epidemiological studies have focused.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in detail in Bray and others (2008). Briefly, we restricted analyses to the period 1983–1997 and, to remove some of the inherent random variability, excluded populations with a mean annual coverage of less than 1 million inhabitants. For the remaining 23 registry populations, incidence data were available by eighteen 5-year age groups (0–4, 5–9, …, 80–84, 85+) and sex for each of the years of diagnosis 1983–1997 (see footnotes of Table 1 for exceptions). Regional registries were aggregated to national or larger area levels on the basis of geographical area, thus enabling sufficient numbers for meaningful age-specific analyses. Five aggregated low-risk areas were defined: North America, Japan, north and west Europe, Australia, and India. To examine the effect of calendar time, the data were further divided into three 5-year diagnostic periods (1983–1987, 1988–1992, 1993–1997).

Table 1.

Number of NPC cases and corresponding number of person–years at risk (in millions) for males and females in 1983–1997

| Area | Cases (M/F) | Person–years (M/F) |

| North America | 2705/1227 | 345.99/354.05 |

| Canada | ||

| Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results white | ||

| Japan | 587/232 | 80.67/83.21 |

| Miyagi | ||

| Osaka | ||

| North and west Europe | 1424/709 | 270.98/285.46 |

| Denmark | ||

| Estonia | ||

| Switzerland, Züricha | ||

| UK, Birmingham and West Midlands | ||

| UK, Merseyside and Cheshire | ||

| UK, North western | ||

| UK, Oxfordb | ||

| UK, South Thames region | ||

| UK, Yorkshire | ||

| UK, Scotland | ||

| Australia | 814/310 | 86.25/87.37 |

| New South Wales | ||

| South | ||

| Victoria | ||

| India | 539/219 | 110.63/93.04 |

| Chennaic | ||

| Mumbaic |

Incidence data available for the years of diagnosis 1983–1996.

Incidence data available for the years of diagnosis 1985–1997.

Population data available in 16 age groups (0–4, 5–9, …, 70–74, 75+).

Table 1 gives an overview of the countries/regions included in the analysis, with the number of NPC cases and corresponding number of person–years at risk (in millions) for males and females in the aggregated areas in 1983–1997. In total, there were 6069 cases among males and 2697 among females. The total number of person–years at risk (in millions) was 894.53 for males and 903.14 for females.

2.2. Statistical methods

Standard frailty theory makes use of the multiplicative frailty model. In this model, the individual hazard rate is the product of an unobservable frailty variable Z and an unobservable basic rate λ(t) common to all individuals; that is, h(t|Z) = Zλ(t) (Aalen, 1994), where t throughout denotes age. The population hazard rate is the net result for a number of individuals with different frailties and is observable, as the age-incidence rate. The basic rate specifies how the hazard changes with age. The level of the hazard for a given individual is specified by the frailty which follows a specific statistical distribution. Common distributions are the power variance function (PVF) distributions, which include the gamma and the compound Poisson distribution as special cases.

To accommodate the bimodality in the age-incidence curve of NPC, we make a minor modification to the multiplicative frailty model by including 2 frailties, assumed for simplicity, to be independent. The first frailty, Z1, represents the risk of developing NPC in very early adulthood, postulated to be a result of genetic and viral factors (Ayan and others, 2003). Later lifestyle factors (including smoking) probably influence the risk of getting NPC for individuals aged 65–74 years, represented by the second frailty term, Z2. We let the individual hazard rate be a linear combination of these 2 frailties,

| (2.1) |

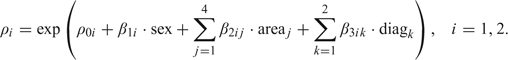

NPC is a rare form of cancer, and to allow individuals to be nonsusceptible, we use the compound Poisson distribution for the frailties Z1 and Z2. This distribution has been successfully applied to testicular cancer and colorectal cancer (Aalen and Tretli, 1999), (Moger and others, 2004), (Svensson and others, 2006). For i = 1,2, let Xi,1,Xi,2,…,Xi,Ni be independent gamma-distributed random variables with scale and shape parameter νi and ηi, respectively. The frailty variables Z1 and Z2 are given by

|

where Ni is a Poisson-distributed random variable with expectation ρi. The Poisson parameters ρi(i = 1,2) determine the proportion of nonsusceptible individuals as P(Zi≠0) = 1 − exp( − ρi).

The age-specific incidence rates of NPC vary by sex and geographic location and, in some populations, with time. Hence, we allowed ρi to change over sex, area, and diagnostic period by including covariates in this parameter. The Poisson parameters can therefore be written as

|

(2.2) |

The process of carcinogenesis can be described by different multistage models, among which the Armitage–Doll (AD) multistage model (Armitage and Doll, 1954) is well known. In this model, cells go through an irreversible process, transforming normal cells into malignant cells via many intermediate states. The AD model does not take into account that cells can replicate, die, or differentiate. The Moolgavkar–Venzon–Knudson (MVK) model is a 2-stage model which allows for clonal expansion of intermediate cells. Both these multistage models are illustrated in Portier and Kopp-Schneider (1991), who also give an expansion of the MVK model to include DNA damage, cell replication, and DNA repair, the damage-fixation multistage model. Little (1995) proposes a generalization of the MVK model which allows an arbitrary number of mutational stages.

Armitage and Doll (1954) justify the use of the Weibull distribution for the basic rates, while Kopp-Schneider (1997) states that the Weibull model is the most commonly used parametric model for carcinogenesis. If we let k be the shape parameter of this distribution, we obtain that λi(t) = kitki − 1, i = 1,2. Usually these hazard rates are written as aikitki − 1, where the as are scale parameters. To avoid overparameterization, these parameters are subsumed in the frailty variables, that is, a1 = a2 = 1.

The individual survival function, given the frailties, is S(t|Z1,Z2) = exp( − Z1Λ1(t) − Z2Λ2(t)), where Λi(t) = ∫0tλi(s)ds = tki, i = 1,2, are the cumulative basic rates. If we integrate out the unknown frailty variables, we get the population survival function

|

(2.3) |

By differentiating the natural logarithm of (2.3) with respect to t and changing the sign, we find the population hazard rate

| (2.4) |

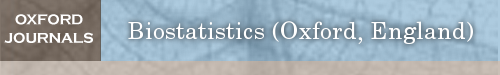

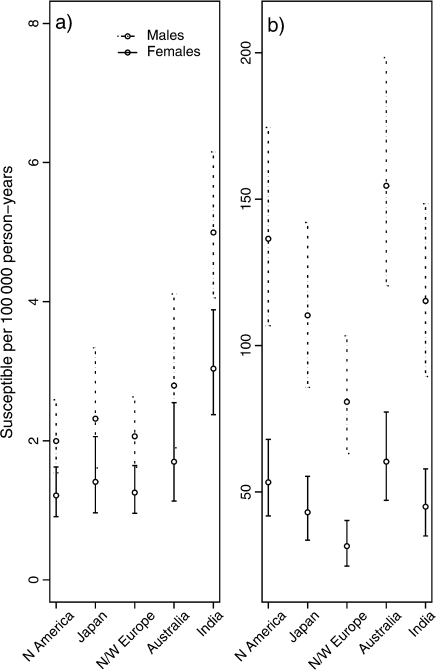

The function in (2.4) is bimodal, as opposed to the individual hazard rate in (2.1) which is monotonic. It is an expansion of the population hazard rate given in Aalen and Tretli (1999). With only one peak in the age-incidence curve, only one of the terms in (2.4) would have been necessary. The Poisson parameter ρ would have been a proportionality factor, and including covariates in this parameter only would have given a proportional hazards model. However, it is possible for ρ1 and/or ρ2 to be proportionality parameters also in the bimodal model. Figure 1(a) shows an example of the hazard function in (2.4). The plot in Figure 1(b) shows the population hazard rates for the 2 peaks separately, that is, for the 2 terms in (2.4). We see that these hazard rates increase up to a certain age after which the curves start to decrease. If we add these hazard rates together, we get the bimodal curve in Figure 1(a). The first peak (from Z1) in the bimodal curve decreases less than the long-dashed line in Figure 1(b), but the second peak (from Z2) is in accordance with the dashed line in Figure 1(b). At all ages where one of the 2 curves is approximately 0, the corresponding term in (2.4) will cancel out. Hence, in this example the Poisson parameter ρ2 is a proportionality factor at, for example, the second peak since the frailty Z1 is 0 at this age, but this will not be the case for ρ1 at the first peak where both Z1 and Z2 contribute to the total curve.

Fig. 1.

Bimodal population hazard rate in (a) (2.4) for certain parameter values. Hazard function for each of the 2 peaks separately in (b), same parameter values as in (a).

The parameters for the frailty distributions and the basic rates are assumed equal for both sexes in all age intervals, areas, and diagnostic periods. From (2.4), we see that the population hazard rates for males and females in area j and diagnostic period k (denoted later as hMjk(t) and hFjk(t), respectively) differ only in the values of the Poisson parameters. Let ρiMjk and ρiFjk be the Poisson parameters for males and females, respectively, in peak i, area j, and diagnostic period k. Further let

| (2.5) |

be the parts of the population hazard rate in (2.4) that are equal for the sexes in all age intervals, areas, and diagnostic periods. Combining (2.4) and (2.5), the hazard ratio between males and females in area j and diagnostic period k becomes

| (2.6) |

The hazard ratio between males in area j and reference area j′, in the same diagnostic period k, is given by

| (2.7) |

The hazard ratios in (2.6) and (2.7) depend on age. They are quite complex because the population hazard rate in (2.4) consists of 2 terms, so generally we cannot cancel out common terms. Parametric bootstrapping is required to obtain corresponding confidence intervals.

The proportion of susceptible individuals follows from the underlying Poisson parameters. Specifically, the probabilities of the individual being susceptible in peak 1 and peak 2 are 1 − exp( − ρ1) and 1 − exp( − ρ2), respectively.

2.3. Estimation procedure

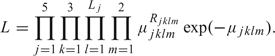

The method is the same as in Aalen and Tretli (1999). Let μjklm and Rjklm be, respectively, the expected and the observed number of NPC cases in area j, diagnostic period k, and age interval l for sex m. Let Tjklm be the corresponding number of person–years at risk. From a Poisson model, the likelihood function is given by

|

The midpoints of the age intervals are denoted by t1,…,t16 or t1,…,t18, depending on the number of age groups. The expected number of NPC cases is defined as the average hazard rate per year for area j, diagnostic period k, age interval l, and sex m, multiplied by the number of person–years,

The likelihood function depends on the parameters through the population survival function given in (2.3). We assume that the Weibull shape parameters ki and the scale and shape parameters νi and ηi of the underlying gamma distributions are the same for both sexes in all age intervals, areas, and diagnostic periods. This gives the same shape of the distributions to reduce the number of parameters. The Poisson parameters ρi (i = 1,2) are allowed to change over sex, area, and diagnostic period according to (2.2). This gives 11 parameters per peak and a total of 22 parameters in the model, which we estimate by maximizing the natural logarithm of the likelihood function, ln(L). The R function “nlminb” is used for the maximization, and standard errors are calculated from the Hessian matrix in the R function “optim.” The parameter estimate divided by the standard error of this estimate gives the Wald test, which is used to test the effect of the covariate by computing 2-sided p-values.

The confidence intervals for the hazard ratios are based on the percentile method. This method uses the α/2 and 1 − α/2 percentiles of the bootstrap sample, in ascending order, if α(B + 1) is an integer (Carpenter and Bithell, 2000). For simplicity, we use B = 999 and a significance level α = 0.05.

3. RESULTS

The reference level for the covariate diagnostic period is 1983–1987. Two-sided p-values for the test of no effect of this covariate in peak 1, adjusted for the covariates sex and area, are 0.25 and 0.24 for the periods 1988–1992 and 1993–1997, respectively. For the second peak, the p-values are 0.14 and 0.09. Hence, there is no significant difference in the age incidence for the three 5-year diagnostic periods. In the following, we therefore analyze data for the aggregated 15-year diagnostic period 1983–1997.

The left part of Table 2 shows the 2-sided p-values for the test of no effect of the covariates sex and area, unadjusted for diagnostic period. For these covariates, Table 2 also gives the hazard ratios, as given in (2.6) and (2.7), at the mean value of the age intervals for the 2 peaks (t = 19.5 and t = 69.5, respectively) with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. The confidence intervals are much wider at age 19.5 than at age 69.5 because of fewer cases. The covariate sex is significant in both peaks with an increased risk for males compared to females. Corresponding to the example in Figure 1, both terms in (2.6) contribute to the hazard ratio at age 19.5, and the effect of sex therefore depends on area of residence. We present the mean hazard ratio over areas to get one combined estimate of 1.89 with (1.50, 2.20) as the 95% confidence interval. At age 69.5, the hazard ratio for sex is 2.56 (2.53,2.74) regardless of area, as the first hazard in (2.6) is approximately 0 at this age. In most areas from which data are available, the reported male:female ratio in the population of individuals who acquire the disease is in the range of 2–3:1 (Hildesheim and Levine, 1993).

Table 2.

P-values for both peaks and hazard ratios at ages t = 19.5 (mean of age interval peak 1) and t = 69.5 (mean of age interval peak 2) with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals of sex and area

|

P-value |

HR(19.5) | HR(69.5) | ||

| Peak 1 | Peak 2 | |||

| Sex. Reference level: women | ||||

| Sex | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.89 [1.50, 2.20] | 2.56 [2.53, 2.74] |

| Area. Reference level: North America | ||||

| Japan | < 0.45 | < 0.001 | 1.02 [0.63, 1.23] | 0.81 [0.79, 0.85] |

| N/W Europe | < 0.81 | < 0.001 | 0.86 [0.64, 0.97] | 0.59 [0.58, 0.60] |

| Australia | < 0.07 | < 0.001 | 1.29 [1.13, 1.84] | 1.13 [1.06, 1.15] |

| India | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.83 [1.30, 2.09] | 0.84 [0.79, 0.90] |

Correspondingly, for the area covariate, we present the mean hazard ratio over sex at age 19.5. From the p-values and the hazard ratios, India is the only area with a significantly higher risk than North America at the first peak. The other possible differences are not significant according to the Wald test, though unity is not included in the confidence interval for north and west Europe and Australia. The results for these 2 tests differ because the hazard ratio in (2.7) is influenced by the parameters in both peaks. The function A2(t) in (2.5) is approximately 0 for small values of t, but this is not the case for t = 19.5. At the second peak (age 69.5), we see significant differences between North America and all the 4 other areas. The 95% confidence intervals support this conclusion; the difference for individuals aged 69.5 years is significant. For t = 69.5, the hazard ratio is mostly influenced by the parameters in the second peak since the function A1(t) in (2.5) is approximately 0 for large values of t. This results in consistent results from p-values and hazard ratios. North America has a higher risk than all the other areas except Australia.

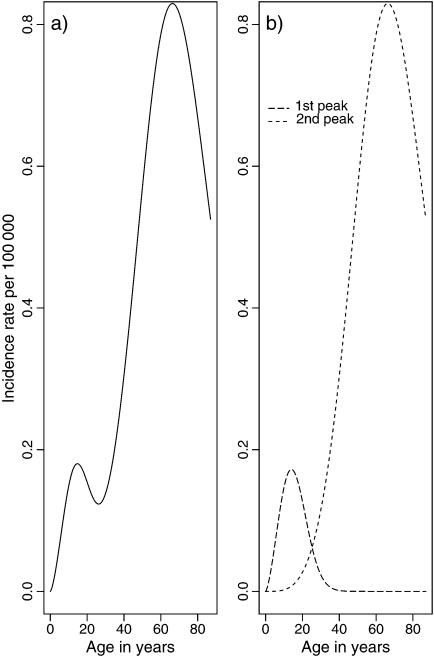

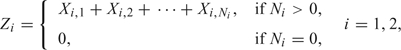

Figure 2 presents 25 bootstrap age-incidence curves, used to calculate bootstrap confidence intervals, together with the observed values. The estimated incidence rates are given by replacing the parameters in (2.4) with their estimated values. These graphs are presented on a semilog-scale to highlight the bimodality. We see less variation for North America than Japan, especially up to the first peak, and the fit is also somewhat better for the former area. This is expected as North America has the highest number of person–years at risk and Japan the lowest (see Table 1). North America contributes therefore the most to the likelihood function and hence the parameter estimates.

Fig. 2.

Observed (discrete points) and 25 bootstrap (continuous curves) age-specific incidence rates per 100 000 person–years for both sexes in North America and Japan. Vertical lines are included to emphasize the rates in age groups 15–24 and 65–74.

The estimates of the other parameters in the compound Poisson model are given in Table 3. The underlying Weibull hazard rate has a shape parameter of 2.48 with 95% confidence interval (2.16,2.80) for the first peak and 4.65 (4.28,5.03) for the second. These confidence intervals are based on a normal approximation and are calculated from the estimates and standard errors in Table 3. Note that exp(β) for the second peak is equal to the hazard ratios given in the last column of Table 2, since the underlying Poisson parameter ρ2 given in (2.2) is a proportionality factor.

Table 3.

Maximum likelihood estimates with standard errors of the parameters

| Parameters | ν | η | k | ρ0 | |

| Peak 1 | |||||

| Estimates | 2.81 × 104 | 23.48 | 2.48 | − 11.32 | |

| se |

4.33 × 104 |

36.70 |

0.16 |

.0.15 |

|

| Peak 2 | |||||

| Estimates | 6.16 × 108 | 01.39 | 4.65 | − 7.54 | |

| se |

2.19 × 108 |

0.95 |

0.19 |

0.12 |

|

| Parameters | β1 | β21 | β22 | β23 | β24 |

| Peak 1 | |||||

| Estimates | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.92 |

| se |

0.10 |

0.20 |

0.14 |

0.18 |

0.13 |

| Peak 2 | |||||

| Estimates | 0.94 | − 0.210 | − 0.52 | 0.12 | − 0.17 |

| se | 0.02 | .0.04 | − 0.03 | 0.04 | − 0.05 |

se, standard error.

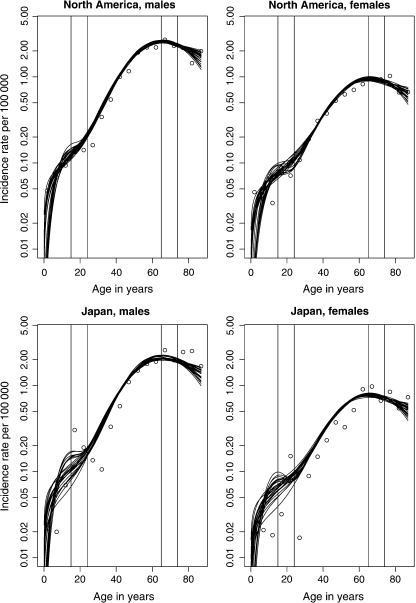

To check the improvement in goodness of fit for a bimodal model over a unimodal model, we also fitted a standard unimodal compound Poisson frailty model with a Weibull baseline hazard to the data. This model has a total of 9 parameters and yielded a log-likelihood of 30067.52. The bimodal model yielded a log-likelihood of 30372.82, a significant improvement over the single-peaked model by the likelihood ratio test (p-value < 0.001). A comparison of the observed and estimated incidence rates for these models illustrate this; in Figure 3, graphs of rates versus age are presented on a semilog-scale. The modified multiplicative frailty model provides an acceptable fit to the data, and we can clearly see the improvement over the unimodal fit. Again, we see a better fit for North America and north and west Europe than for the other areas.

Fig. 3.

Observed (discrete points) and estimated (continuous curves) age-specific incidence rates per 100 000 person–years for both sexes in 5 low-risk areas. Solid (dashed) line is from a bimodal (unimodal) fit. Vertical lines are included to emphasize the rates in age groups 15–24 and 65–74.

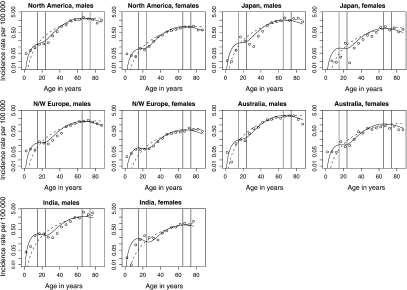

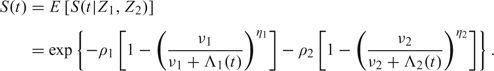

In Figure 4, we have plotted the estimated proportion of susceptible males and females per 100000 person–years, with error bars giving the 95% confidence intervals. These intervals are log transformed since the proportions of susceptible individuals are relatively small and the coefficients of variation for these values are relatively large. In all 5 aggregated low-risk areas, for both peaks, there is a higher frailty proportion among males than females, reflecting the higher incidence among males. In peak 1, North America has the lowest proportion of frail individuals and India the highest. The hazard ratio at age 19.5 gave significantly higher risk for India than North America. North and west Europe has the lowest proportion of frail individuals and Australia the highest in the second peak.

Fig. 4.

Estimated proportion of susceptible males and females per 100 000 person–years (circles) in (a) peak 1 and (b) peak 2. The error bars give the log-transformed 95% confidence intervals.

4. DISCUSSION

The principal finding of the present study is that NPC incidence rates in low-risk populations are well described by a bimodal frailty model in both males and females diagnosed over the period 1983–1997. It is necessary to discuss the relevance of the assumptions of the model since other models built on an alternative set of assumptions may also fit the data.

The key assumption of a frailty model implies that only a certain proportion of individuals are susceptible to develop NPC at a given age during their lifetime. Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of this disease. The link between the NPC and the EBV is well known (Chang and Adami, 2006), (Hildesheim and Levine, 1993). EBV belongs to the herpes virus family and is one of the most common human viruses. This virus is ubiquitous worldwide, and many individuals are infected during their lifetime. Only a small proportion of individuals develop NPC, however, so EBV is not a sufficient cause of NPC. In high-risk populations where undifferentiated carcinomas or lymphoepitheliomas (Type-I NPC tumors) are common, genetic events appear to occur early in NPC pathogenesis and may cause predisposition to subsequent EBV infection. It may be speculated that EBV is a necessary factor for those histological types of NPC where stable infection of epithelial cells by EBV requires such an altered, undifferentiated cellular environment (Lo and Huang, 2002 Young and Rickinson, 2004).

In the low-risk settings studied here, however, type-III tumors—keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas—dominate, particularly at older ages (the late peak in age incidence), and there is an inconsistent relationship between the EBV infection and the development of these tumors (Chang and Adami, 2006).

Genetic and/or other environmental cofactors must additionally contribute to the risk of NPC. The first peak in individuals diagnosed in late adolescence or early adulthood would imply a role for germline mutations (major genes) and gene polymorphisms (minor genes), see Chan and others (2005) and Bray and others (2008). EBV infection seems likely to contribute to NPC in this young age group (Ayan and others, 2003), where type-III cancer is the more commonly diagnosed type (linked with the early peak in age incidence). The second later peak relates more to lifestyle-related risk determinants, including tobacco and alcohol consumption and, more speculatively, occupational exposures to carcinogens, such as formaldehyde (Chang and Adami, 2006).

Another assumption of our model is independence between frailties. This assumption provides a simplification of the model, as with the population survival function in (2.3). Usually, bimodal age-incidence curves are the integrated effect of the 2 different underlying unimodal population distributions, corresponding to the early and late peak. In such cases, the 2 distributions tend to represent different aetiologies, as discussed for Hodgkin's lymphoma (MacMahon, 1966). In this instance, it seems reasonable that the 2 peaks of the NPC age-incidence curves differ substantially in terms of aetiology. This argument, together with the fact that the distance between the age intervals for the peaks is large, makes the assumption of independence sensible. If EBV infection is a common factor in the pathway of both populations, the shape of the age-incidence curves may also be influenced by the timing of events including age at infection, specific genetic events, and, possibly, environmental exposures.

The underlying assumption of the frailty modeling is the mechanistic understanding of cancer as a result of accumulated genetic damage, generally regarded as the multistage clonal expansion model of carcinogenesis. The biological interpretation of the k parameter is the number of genetic and epigenetic events required on average for a cell to become malignant (Armitage and Doll, 1954), although this interpretation should be suitably cautious for more complex multistage models. In previous frailty model studies, the estimated parameter values have been in accordance with current knowledge regarding carcinogenesis of the specific neoplasm, that is, testicular cancer (Aalen and Tretli, 1999) and colorectal cancer (Svensson and others, 2006). In the current study, the estimated k-values of 2.5 and 4.7 for the first and second peak, respectively, compare with a k-value of 3.0 from a previous simulation study on a sample of low-risk western populations reported by Doll (1971). At this time, the uniformity of bimodality among NPC cases in low-risk populations was certainly not recognized, and Doll's estimate (assuming a unimodal distribution) lies between our estimates derived using a bimodal distribution.

The k parameter of 2–3 for the early peak in the age-incidence curve may be interpreted biologically as a reflection of the 2 crude `hits’ in the carcinogenesis, that is, the genetic alterations involving major or minor susceptibility genes and a promoting effect of EBV infection. The pathogenesis leading to the late peak in the age-incidence curve is thought to be related more to the effect of environmental carcinogens possibly interacting with EBV infection. This is illustrated in Figure 4 of Bray and others (2008). It is quite plausible that environmental cofactors in the population as a whole may provide (on average) 2 more `hits', for example, loss of heterozygosity in certain genes and/or other genetic changes as described by Young and Rickinson (2004) and Chan and others (2005).

Earlier studies have concluded that the incidence of NPC in the population of individuals who acquire the disease is 2- to 3-fold higher in males than females (Chang and Adami, 2006), (Hildesheim and Levine, 1993). We have found a similar increased risk for males up to the second peak (t = 69.5 years) compared to females. A general explanation could be the tendency for less favorable smoking and alcohol consumption patterns among males. The close to doubling of risk for susceptible individuals among males up to the first peak (t = 19.5 years) is intriguing but not readily explained given present knowledge.

Finally, the bimodal frailty model developed in this paper was applied to NPC age incidence to examine susceptibility among low-risk populations. However, the model may be applied to any disease condition where the bimodality of the age-occurrence pattern can be demonstrated at the population level. For cancer, such a phenomenon is not unique to NPC; there are a number of cancer forms that exhibit 2 peaks in incidence rates followed by respective declines subsequently, and a frailty approach to their study would certainly seem warranted. Examples from cancer often involve a putative early viral component. These include Hodgkin's lymphoma, which has long been established as bimodal (MacMahon, 1966), with a relatively high proportion of cases occurring in adolescents and young adults, particularly in higher-resource countries. More recent candidates include hairy cell leukaemia (Dores and others, 2008), female breast carcinoma (Anderson and others, 2006), and Ewing's sarcoma (Cope, 2000).

FUNDING

Statistics for Innovation (sfi)2 to M.H.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the population-based cancer registries worldwide that submitted their data to successive volumes of Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. The authors thank Bjarte Aagnes at the Cancer Registry of Norway for providing the data. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Aalen OO. Heterogeneity in survival analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 1988;7:1121–1137. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780071105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aalen OO. Effects of frailty in survival analysis. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1994;3:227–243. doi: 10.1177/096228029400300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aalen OO, Tretli S. Analyzing incidence of testis cancer by means of a frailty model. Cancer Causes and Control. 1999;10:285–292. doi: 10.1023/a:1008916718152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WF, Pfeiffer RM, Dores GM, Sherman ME. Comparison of age distribution patterns for different histopathologic types of breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15:1899–1905. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage P, Doll R. The age distribution of cancer and a multi-stage theory of carcinogenesis. British Journal of Cancer. 1954;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1954.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayan I, Kaytan E, Ayan N. Childhood nasopharyngeal carcinoma: from biology to treatment. Lancet Oncology. 2003;4:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)00956-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Haugen M, Moger TA, Tretli S, Aalen OO, Grotmol T. Age-incidence curves of nasopharyngeal carcinoma worldwide: bimodality in low-risk populations and aetiologic implications. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17:2356–2365. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J, Bithell J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Statistics in Medicine. 2000;19:1141–1164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000515)19:9<1141::aid-sim479>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JKC, Bray F, McCarron P, Foo W, Lee AWM, Yip T, Kuo TT, Pilch BZ, Wenig BM, Huang D. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In: Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chang ET, Adami H-O. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15:1765–1777. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope JU. A viral etiology for Ewing's sarcoma. Medical Hypotheses. 2000;55:369–372. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R. The age distribution of cancer: implications for models of carcinogenesis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (General) 1971;134:133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Dores GM, Matsuno RK, Weisenburger DD, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Hairy cell leukaemia: a heterogeneous disease? British Journal of Haematology. 2008;142:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildesheim A, Levine PH. Etiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1993;15:466–485. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard P. Analysis of Multivariate Survival Data. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp-Schneider A. Carcinogenesis models for risk assessment. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1997;6:317–340. doi: 10.1177/096228029700600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little MP. Are two mutations sufficient to cause cancer? Some generalizations of the two-mutation model of carcinogenesis of Moolgavkar, Venzon, and Knudson, and of the multistage model of Armitage and Doll. Biometrics. 1995;51:1278–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo K-W, Huang DP. Genetic and epigenetic changes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2002;12:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s1044579x02000883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon B. Epidemiology of Hodgkin's disease. Cancer Research. 1966;26:1189–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moger TA, Aalen OO, Heimdal K, Gjessing HK. Analysis of testicular cancer data using a frailty model with familial dependence. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:617–632. doi: 10.1002/sim.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Storm H. Vol. I. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, to VIII, IARC CancerBase No. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Portier CJ, Kopp-Schneider A. A multistage model of carcinogenesis incorporating DNA damage and repair. Risk Analysis. 1991;11:535–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1991.tb00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson E, Moger TA, Tretli S, Aalen OO, Grotmol T. Frailty modelling of colorectal cancer incidence in Norway: indications that individual heterogeneity in risk is related to birth cohort. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;21:587–593. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LS, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4:757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]