Abstract

An active site aspartate residue, Asp97, in the methionine aminopeptidase (MetAPs) from Escherichia coli (EcMetAP-I) was mutated to alanine, glutamate, and asparagine. Asp97 is the lone carboxylate residue bound to the crystallographically determined second metal-binding site in EcMetAP-I. These mutant EcMetAP-I enzymes have been kinetically and spectroscopically characterized. Inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy analysis revealed that 1.0 ± 0.1 equivalents of cobalt were associated with each of the Asp97-mutated EcMetAP-Is. The effect on activity after altering Asp97 to alanine, glutamate or asparagine is, in general, due to a ~ 9000-fold decrease in kca towards Met-Gly-Met-Met as compared to the wild-type enzyme. The Co(II) d–d spectra for wild-type, D97E and D97A EcMetAP-I exhibited very little difference in form, in each case, between the monocobalt(II) and dicobalt(II) EcMetAP-I, and only a doubling of intensity was observed upon addition of a second Co(II) ion. In contrast, the electronic absorption spectra of [Co_(D97N EcMetAP-I)] and [CoCo(D97N EcMetAP-I)] were distinct, as were the EPR spectra. On the basis of the observed molar absorptivities, the Co(II) ions binding to the D97E, D97A and D97N EcMetAP-I active sites are pentacoordinate. Combination of these data suggests that mutating the only nonbridging ligand in the second divalent metal-binding site in MetAPs to an alanine, which effectively removes the ability of the enzyme to form a dinuclear site, provides a MetAP enzyme that retains catalytic activity, albeit at extremely low levels. Although mononuclear MetAPs are active, the physiologically relevant form of the enzyme is probably dinuclear, given that the majority of the data reported to date are consistent with weak cooperative binding.

Keywords: EPR, kinetics, mechanism, methionine aminopeptidases, mutants

Methionine aminopeptidases (MetAPs) represent a unique class of protease that is responsible for the hydrolytic removal of N-terminal methionines from proteins and polypeptides [1–4]. In the cytosol of eukaryotes, all proteins are initiated with an N-terminal methionine; however, all proteins synthesized in prokaryotes, mitochondria and chloroplasts are initiated with an N-terminal formylmethionyl that is subsequently removed by a deformylase, leaving a free methionine at the N-terminus [2]. The cleavage of this N-terminal methionine by MetAPs plays a central role in protein synthesis and maturation [5,6]. The physiological importance of MetAP activity is underscored by the cellular lethality upon deletion of the MetAP genes in Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [7–10]. Moreover, a MetAP from eukaryotes has been identified as the molecular target for the antiangiogenesis drugs ovalicin and fumagillin [11–15]. Therefore, the inhibition of MetAP activity in malignant tumors is critical in preventing tumor vascularization, which leads to the growth and proliferation of carcinoma cells. In comparison to conventional chemotherapy, antiangiogenic therapy has a number of advantages, including low cellular toxicity and a lack of drug resistance [14].

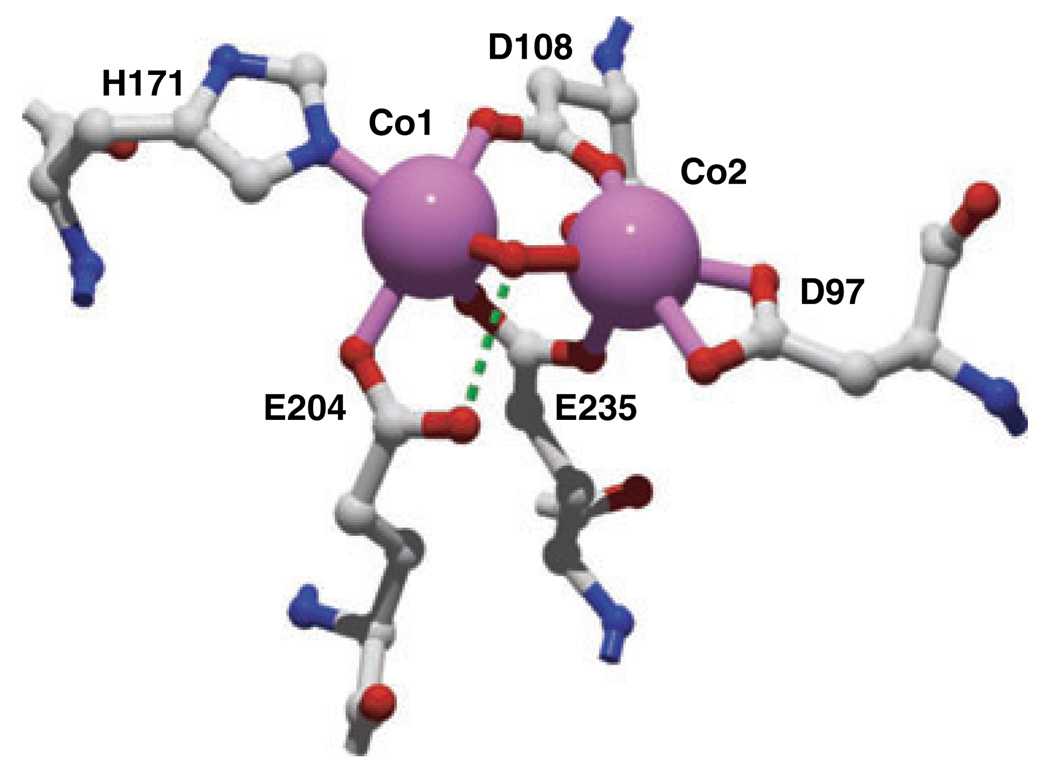

MetAPs are organized into two classes (type I and type II) on the basis of the absence or presence of an extra 62 amino acid sequence (of unknown function) inserted near the catalytic domain of type II enzymes. The type I MetAPs from E. coli (EcMetAP-I), Staphylococcus aureus, Thermotoga maritima and Homo sapiens and the type II MetAPs from Homo sapiens and Pyrococcus furiosus (PfMetAP-II) have been crystallographically characterized [14,16–21]. All six display a novel ‘pita-bread’ fold with an internal pseudo-two-fold symmetry that structurally relates the first and second halves of the polypeptide chain to each other. Each half contains an antiparallel β-pleated sheet flanked by two helical segments and a C-terminal loop. Both domains contribute conserved residues as ligands to the divalent metal ions residing in the active site. Nearly all of the available X-ray crystallographic data reported to date reveal a bis(µ-carboxylato) (µ-aquo/hydroxo) dinuclear core with an additional carboxylate residue at each metal site and a single histidine bound to M1 (Fig. 1) [22,23]. However, extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy (EXAFS) studies on Co(II)- and Fe(II)-loaded EcMetAP-I did not reveal any evidence for a dinuclear site [23]. An X-ray crystal structure of EcMetAP-I was recently reported with partial occupancy (40%) of a single Mn(II) ion bound in the active site [24]. This structure was obtained by adding the transition state analog inhibitor l-norleucine phosphonate, in order to impede divalent metal binding to the second site, and by limiting the amount of metal ion present during crystal growth. This structure provides the first structural verification that MetAPs can form mononuclear active sites and that the single divalent metal ion resides on the His171 side of the active site, as previously predicted by 1H-NMR spectroscopy and EXAFS [22,23].

Fig. 1.

Active site of EcMetAP-I showing the metal-binding residues, including Asp97. Prepared from Protein Data Bank file 2MAT.

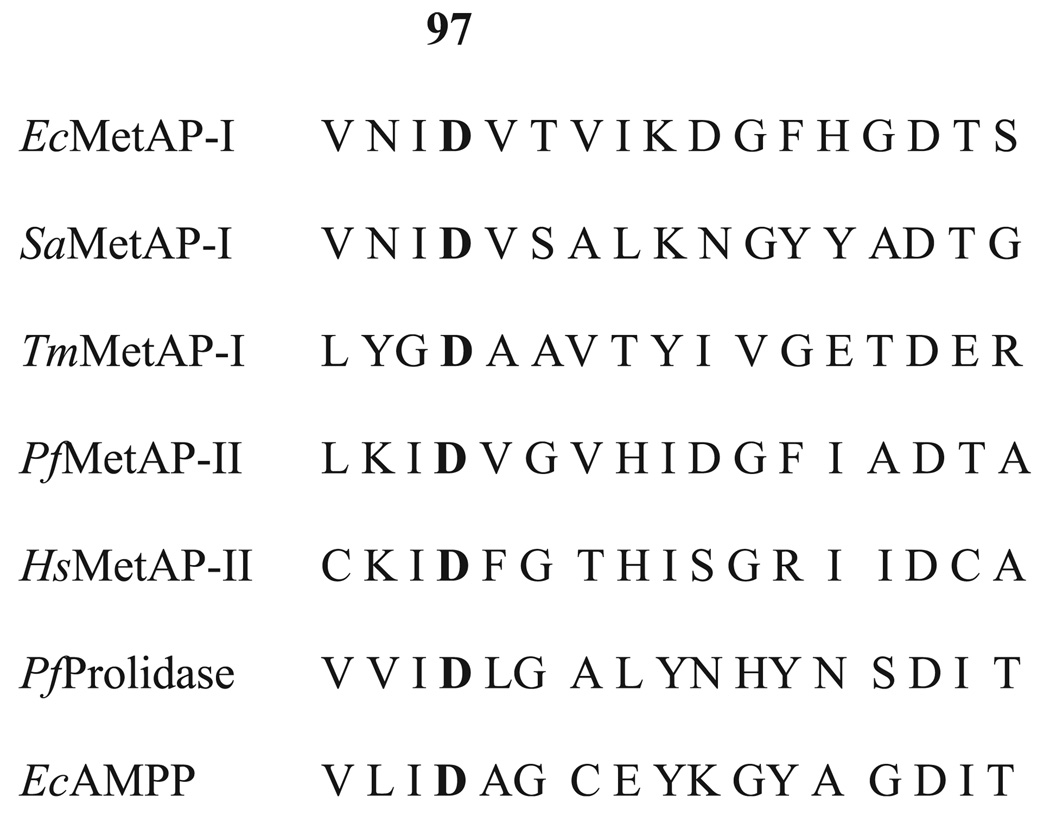

A major controversy currently surrounding MetAPs is whether a mononuclear site, a dinuclear site or both can catalyze the cleavage of N-terminal methionines in vivo [22,25,26]. A growing number of kinetic studies indicate that both type I and type II MetAPs are fully active in the presence of only one equivalent (eq.) of divalent metal ion [Mn(II), Fe(II), or Co(II)] [22,25,27]. However, kinetic, magnetic CD (MCD) and atomic absorption spectrometry data indicated that Co(II) ions bind to EcMetAP-I in a weakly cooperative fashion (Hill coefficients of 1.3 or 2.1) [26,28]. These data represent the first evidence that a dinuclear site can form in EcMetAP-I under physiological conditions. Moreover, EPR data recorded on Mn(II)-loaded EcMetAP-I and PfMetAP-II suggest a small amount of dinuclear site formation after the addition of only a quarter equivalent of Mn(II) [22,29,30]. In order to determine whether a dinuclear site is required for enzymatic activity in MetAPs, the conserved aspartate, which is the lone nonbridging ligand for the M2 site in MetAPs (Fig. 2), was mutated in EcMetAP-I to alanine, glutamate, and asparagine.

Fig. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment for selected MetAPs, prolidase and aminopeptidase P (AMPP). Prepared from Protein Data Bank files 1C21, 1QXZ, 1O0X, 1XGO, 1BN5, 1PV9, and 1A16.

Results

Metal content of mutant EcMetAP-I enzymes

The number of tightly bound divalent metal ions was determined for each of the mutant EcMetAP-I enzymes by inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) analysis. Apoenzyme samples (30 µm), to which 2–30 eq. of Co(II) were added under anaerobic conditions, were dialyzed for 3 h at 4 °C with Chelex-100-treated, metal-free Hepes buffer (25 mm Hepes, 150 mm KCl, pH 7.5). ICP-AES analysis revealed that 1.0 ± 0.1 eq. of cobalt was associated with each of the Asp97-mutated EcMetAP-I enzymes. As a control, metal analyses were also performed on the corresponding Asp82 mutant PfMetAP-II enzymes. ICP-AES analysis of D82A, D82N and D82E PfMetAP-II also revealed that 1.0 ± 0.1 eq. of cobalt was associated with the enzymes.

Kinetic analysis of the mutant EcMetAP-I enzymes

The specific activities of D97A, D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I were examined using Met-Gly-Met-Met (MGMM) as the substrate. Apo-forms of the variants were all catalytically inactive. Kinetic parameters were determined for the Co(II)-reconstituted wild-type and mutated enzymes (Table 1). In order to obtain detectable activity levels, reactions of D97A, D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I with MGMM were allowed to run for > 24 h before quenching of the reactions, as compared to 1 min for wild-type EcMetAP-I. The extent of the reaction for the variants was obtained from the time dependence of the activity of the enzymes. A linear correlation was observed between activity and time until 30 h, after which the activity values reached a plateau. As a control, substrate was incubated with apo-EcMetAP-I and in buffer, neither of which resulted in any observed substrate cleavage. All three variants exhibited maximum catalytic activity after the addition of only one equivalent of Co(II), which is identical to what was found with wild-type EcMetAP-I [22,31].

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for Co(II)-loaded wild-type (WT) and D97 mutated EcMetAP-I towards MGMM at 30 °C and pH 7.5. SA, specific activity.

| EcMetAP-I | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | D97A | D97N | D97E | |

| Km (mm) | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| kcat (s−1) | 18.3 ± 0.5 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.001 ± 0.0005 | 0.002 ± 0.001 |

| kcat / Km (m−1·s−1) | 6.0 × 103 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SA (units·mg−1) | 36.1 ± 2 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

The effect on activity after altering Asp97 to alanine, glutamate or asparagine is, in general, due to a decrease in kcat. The kcat values for D97A, D97E and D97N EcMetAP-I are 0.003 ± 0.001, 0.002 ± 0.001, and 0.001 ± 0.0005 s−1, respectively (Table 1). Thus, the kcat value for the variants towards MGMM decreased ~ 9000-fold as compared to the wild-type enzyme. For comparison purposes, kcat values of D82E, D82N and D82A PfMetAP-II were determined, and were found to be 10 ± 1, 1.4 ± 0.1, and 0.01 ± 0.005 s−1, respectively. Thus, the kcat value for D82A PfMetAP-II towards MGMM decreased ~ 19 000-fold as compared to wild-type PfMetAP-II, whereas D82E PfMetAP-II was only 19-fold less active. As a control, we also altered the PfMetAP-II active site histidine (His153), which is analogous to His171 in EcMetAP-I, to an alanine. This mutation, not surprisingly, resulted in the complete loss of enzymatic activity. Moreover, this enzyme does not bind divalent metal ions, as determined by ICP-AES analysis. These data clearly establish His153 (His171) as an essential active site amino acid involved in metal binding.

The Km values for each of D97A, D97E and D97N EcMetAP-I decreased in comparison to that of wild-type EcMetAP-I, with the largest drop in Km being observed for D97N EcMetAP-I (0.6 ± 0.1 mm), which contains the most conservative substitution. The observed Km value for D97E EcMetAP-I was 1.8 ± 0.1 mm, whereas D97A EcMetAP-I exhibited a Km value of 1.1 ± 0.1 mm. Combination of the observed kcat and Km values for each EcMetAP-I variant provided the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) for the Co(II)-loaded enzymes, which was decreased 2000-fold, 6100-fold and 3000-fold for D97A, D97E and D97N EcMetAP-I, respectively, towards MGMM. In order to confirm the accuracy of the Km values, the dissociation constant (Kd) for MGMM binding to Co(II)-loaded D97N EcMetAP-I was determined by isothermal calorimetry (ITC) and found to be 0.9 mm, which is similar in magnitude to the observed Km value.

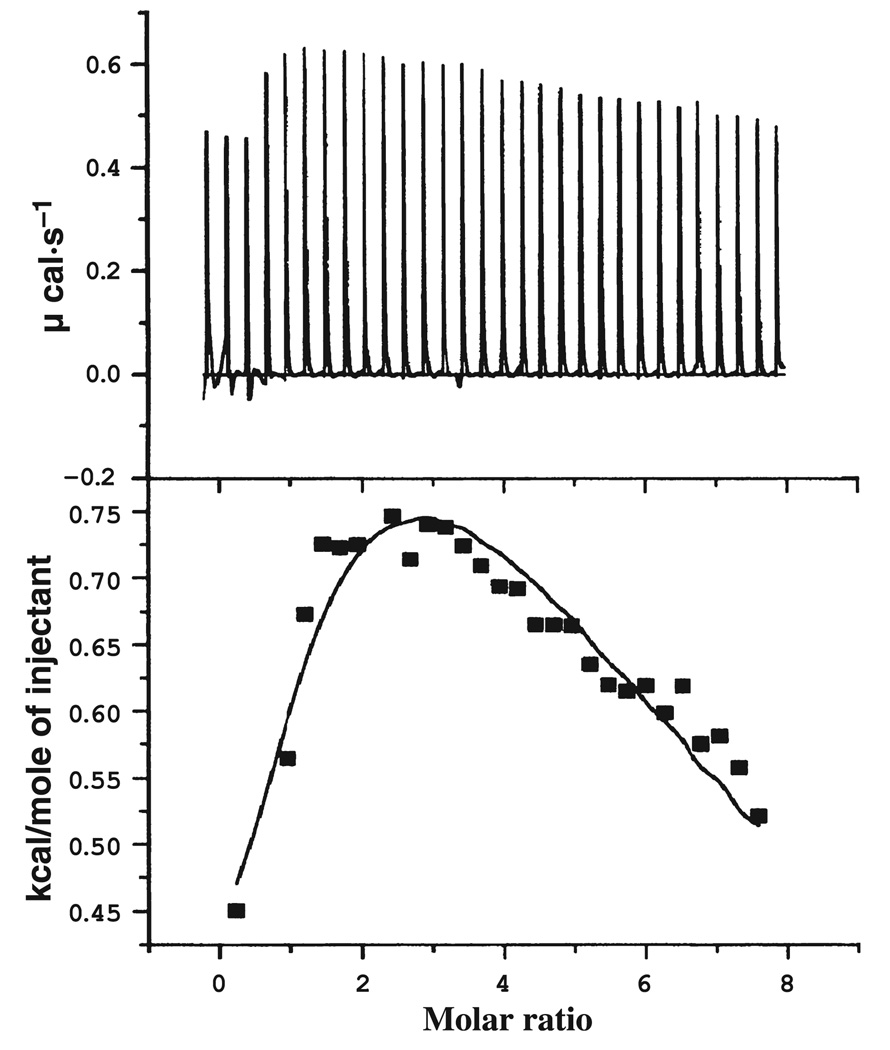

Determination of metal-binding constants

ITC measurements were carried out at 25 ± 0.2 °C for D97E, D97A and D97N EcMetAP-I (Fig. 3). Association constants (Ka) for the binding of Co(II) were obtained by fitting these data, after subtraction of the background heat of dilution, via an iterative process using the origin software package. This software package uses a nonlinear least-square algorithm that allows the concentrations of the titrant and the sample to be fitted to the heat-flow-per-injection to an equilibrium binding equation for two sets of noninteracting sites. The Ka value, the metal–enzyme stoichiometry (p) and the change in enthalpy (ΔH°) were allowed to vary during the fitting process (Table 2, Fig. 3). The best fit obtained for D97A EcMetAP-I provided an overall p-value of 2 for two noninteracting sites, whereas the best fit obtained for D97N EcMetAP-I provided an overall p-value of 3 for three noninteracting sites. Similarly, the best fit obtained for D97E EcMetAP-I provided an overall p-value of 3 for three interacting sites. For D97A EcMetAP-I, Kd values of 1.6 ± 1.2 µm and 2.2 ± 0.4 mm were observed, whereas D97N EcMetAP-I gave a Kd value of 0.22 ± 0.3 µm and two Kd values of 0.2 ± 0.1 mm. Interestingly, D97E EcMetAP-I exhibited cooperative binding, giving Kd values of 90 ± 20, 210 ± 100 and 574 ± 150 µm. The heat of reaction, measured during the experiment, was converted into other thermodynamic parameters using the Gibbs free energy relationship. The thermodynamic parameters obtained from ITC titrations of Co(II) with wild-type EcMetAP-I and each mutant enzyme reveal changes that affect both of the metal-binding sites (Table 3). Although the predominant effect is on the second metal-binding site, substitution of Asp97 by glutamate and asparagine makes the process of binding of the metal ions, particularly for the second metal ion, more spontaneous on the basis of more negative Gibbs free energy (ΔG) values in comparison to the wild-type enzyme. Substitution of Asp97 by alanine does not affect the ΔG value for the binding of the first metal ion; however, the entropic factor (TΔS) for the binding of the first metal ion decreases in the relative order D97E > wild type > D97N > D97A. In addition, TΔS for binding of the second metal ion significantly decreases for D97N EcMetAP-I but remains similar in magnitude for D97E EcMetAP-I in comparison to the wild-type enzyme.

Fig. 3.

ITC titration of 70 µm solution of D97E EcMetAP-I with a 5 mm Co(II) solution at 25 °C in 25 mm Hepes (pH 7.5) and 150 mm KCl.

Table 2.

Dissociation constants (Kd) and metal–enzyme stoichiometry (n) for Co(II) binding to wild-type (WT) and variant EcMetAP-I. For each set of data for both WT and variant EcMetAP-I, p is the number of Co(II) ions per protein. Data for p = 1 are for one Co(II) ion that bound tightly, and data for p = 2 represent two Co(II) ions binding to sites on the protein with lower affinity. WT data have been reported in [49].

| EcMetAP-I | p | Kd1, Kd2 (µm) |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 1 | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

| 2 | 14 000 ± 5000 | |

| D97A | 1 | 1.6 ± 1.2 |

| 1 | 2237 ± 476 | |

| D97N | 1 | 0.22 ± 0.3 |

| 2 | 238 ± 100 | |

| D97E | 1 | 90 ± 20 |

| 1 | 210 ± 100 | |

| 1 | 574 ± 150 |

Table 3.

Thermodynamic parameters for Co(II) binding to wild-type (WT) and variant EcMetAP-I.

| EcMetAP-I | p | ΔH1, ΔH2 (kcal / mol) |

TΔS1,TΔS2 (kcal·mol−1) |

ΔG1, ΔG2 (kcal·mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1 | 1.54 × 101 | 2.33 × 101 | −7.91 |

| 2 | 1.06 × 103 | 1.06 × 103 | −2.51 | |

| D97A | 1 | 1.42 × 100 | 9.35 × 100 | −7.90 |

| 1 | 1.64 × 101 | 2.00 × 101 | −3.61 | |

| D97N | 1 | 1.40 × 100 | 1.05 × 101 | −9.07 |

| 2 | 4.20 × 100 | 9.14 × 100 | −4.94 | |

| D97E | 1 | 6.31 × 10−1 | 8.12 × 103 | −5.49 |

| 1 | 5.03 × 100 | 10.02 × 103 | −4.99 | |

| 1 | 6.20 × 100 | 10.60 × 103 | −4.40 |

Electronic absorption spectra of Co(II)-loaded mutated EcMetAP-I

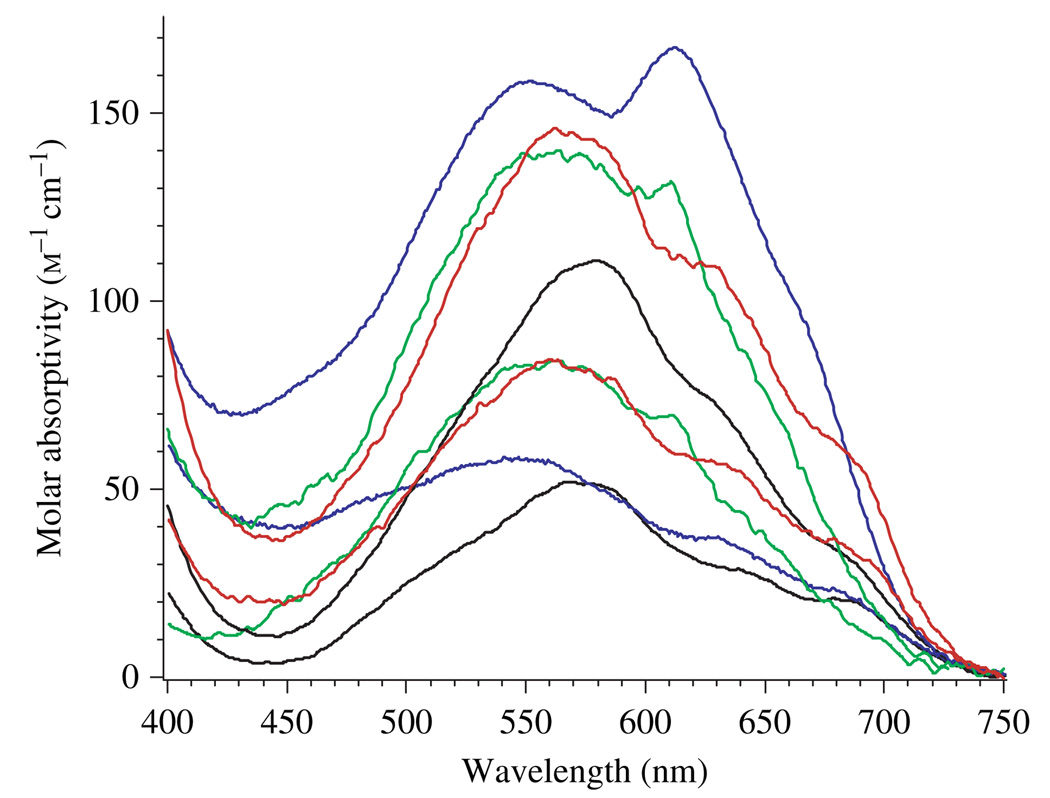

The electronic absorption spectra of wild-type, D97A, D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I with the addition of one and two equivalents of Co(II) were recorded under strict anaerobic conditions in 25 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.5) and 150 mm KCl (Fig. 4). The addition of one equivalent of Co(II) to wild-type, D97A, D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I provided electronic absorption spectra with three absorption maxima between 540 and 700 nm, with molar absorptivities ranging from 20 to 80 m−1·cm−1. In general, the addition of a second equivalent of Co(II) increased the molar absortivities of the absorption bands. However, for D97N EcMetAP-I, molar absorptivity increased for maxima at 550 and 630 nm but diminished for the maxima at 690 nm (Fig. 4). Addition of further equivalents of Co(II) led to precipitation for D97N EcMetAP-I, no change in molar absorptivity of the absorption maxima for D97A EcMetAP-I, but an increase in molar absorptivity for D97E EcMetAP-I.

Fig. 4.

Electronic absorption spectra of 1 mm wild-type (black), D97A (green), D97N (blue) and D97E (red) EcMetAP-I with increments of one and two equivalents of Co(II) in 25 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.5) and 150 mm KCl.

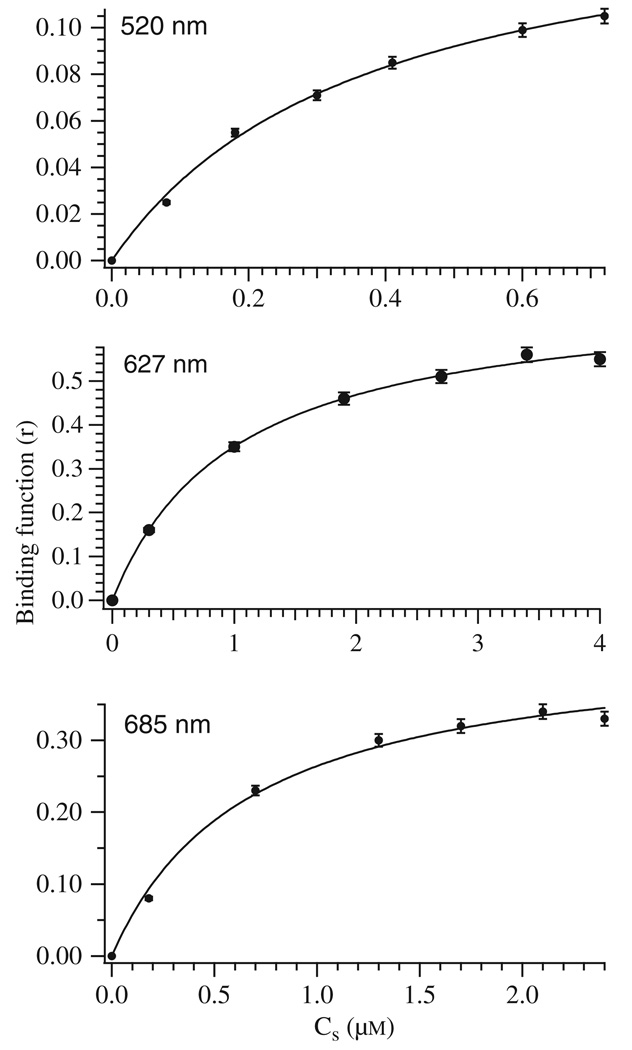

For D97E EcMetAP-I, the dissociation constant for the second metal-binding site was determined by subtraction of the UV–visible spectrum with one equivalent of Co(II) from the other spectra and then plotting a binding curve (Fig. 5). The dissociation constants (Kd) for the second divalent metal-binding sites of EcMetAP-I D97E were obtained by fitting the observed molar absorptivities to Eqn (1), via an iterative process that allows both Kd and p to vary (Fig. 5):

| (1) |

where p is the number of sites for which interaction with M(II) is governed by the intrinsic dissociation constant Kd, and r is the binding function calculated by conversion of the fractional saturation (fa) [32]:

| (2) |

CS, the free metal concentration, was calculated from

| (3) |

where CTS and CA are the total molar concentrations of metal and enzyme, respectively. The best fit obtained for the λmax values at 520, 627 and 685 nm provided a P-value of 1 and Kd values of 0.3 ± 0.1, 1.1 ± 0.2 and 0.6 ± 0.6 mm, respectively, for D97E EcMetAP-I (Table 4).

Fig. 5.

Binding function r versus CS, the concentration of free metal ions in solution for D97E EcMetAP-I in 25 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.5) and 150 mm KCl at three different wavelengths. The solid lines correspond to fits of each data set to Eqn (3).

Table 4.

Data obtained for the fits of electronic absorption data to Eqn (1).

| λmax (nm) | Kd (mm) |

|---|---|

| 520 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| 627 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| 685 | 0.6 ± 0.6 |

EPR studies of Co(II)-loaded D97A, D97E and D97N EcMetAP-I

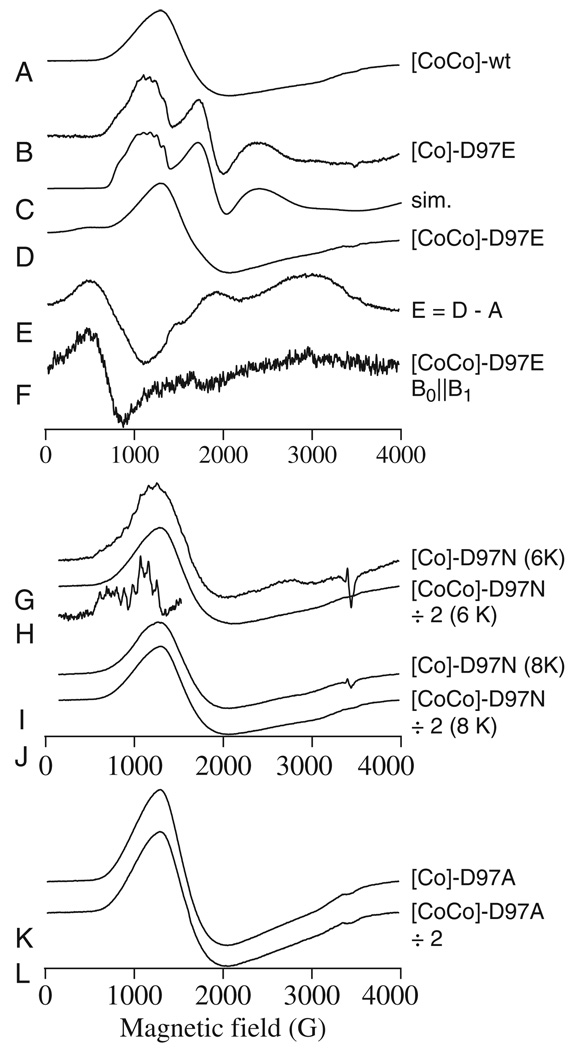

The EPR spectrum of wild-type EcMetAP-I (Fig. 6A) has been well characterized [22], and the form of the signal is invariant from 0.5 to 2.0 eq. of Co(II). The signal is due to transitions in the MS = | ± 1/2〉 Kramers’ doublet of S = 3/2, with Δ > gβBS, and exhibits no resolved rhombicity or 59Co hyperfine structure. This type of signal is typical for protein-bound five- or six-coordinate Co(II) with one or more water ligands. A very similar signal was obtained with the mono-Co(II) form of D97A EcMetAP-I (Fig. 6K) and with the di-Co(II) forms of both D97A (Fig. 6L) and D97N (Fig. 6H,J) EcMetAP-I.

Fig. 6.

Co(II)-EPR of EcMetAP-I and variants. Traces A, B and D are the EPR spectra of [CoCo(WT-EcMetAP-I)] (A), [Co_(D97E-EcMetAP-I)] (B), and [CoCo(D97E-EcMetAP-I)] (D). Trace C is a computer simulation of B assuming two species. The major species exhibited resolved hyperfine coupling and was simulated with spin Hamiltonian parameters S = 3/ 2, MS = |± 1/ 2〉, gx,y = 2.57, gz = 2.67, D >> g BS (50 cm-1), E / D = 0.185, Ay = 9.0 × 10−3 cm−1. The minor species was best simulated (gx,y = 2.18, gz = 2.6, E / D = 1/ 3, Ay (unresolved) = 4.5 × 10−3 cm−1) assuming some unresolved hyperfine coupling, although no direct evidence for this was obtained. Trace E is of spectrum D with arbitrary amounts of spectrum A subtracted. Trace F is the experimental EPR spectrum of [CoCo(D97E- EcMetAP-I)] recorded in parallel mode (B0║ B1). Traces G and I are spectra of [Co_(D97N- EcMetAP-I)], and traces H and J are spectra of [CoCo(D97N- EcMetAP-I)]; the insert of H shows the hyperfine region of G expanded. Trace K is the spectrum of [Co_(D97A- EcMetAP-I)], and L is of [CoCo(D97A-EcMetAP-I)]. Spectra A, B, D and I–K were recorded using 0.2 mW power at 8 K. Spectrum F was recorded using 20 mW at 8 K, and spectra G and H were recorded using 2 mW at 6 K. Trace G is shown × 2 compared to H, I is shown × 2 compared to J, and K is shown × 2 compared to L. Other intensities are arbitrary. Spectrum F was recorded at 9.37 GHz whereas all other experimental spectra were at 9.64 GHz.

The EPR signals from D97E EcMetAP-I were, however, significantly different from those of wild-type EcMetAP-I. The signal observed for [Co_(D97E EcMetAP-I)] (Fig. 6B) was complex, and computer simulation (Fig. 6C) suggested a dominant species that exhibited marked rhombic distortion of the axial zero-field splitting (E/D = 0.185) and a 59Co hyperfine interaction of 9 × 10−3 cm−1. These parameters are typical for low-symmetry five-coordinate Co(II) with a constrained ligand sphere, and suggest that either Co(II) is displaced relative to that in [Co_(wild-type EcMetAP-I)] and binds in a very different manner altogether, or that the binding mode of the carboxylate differs, perhaps being bidentate in D97E EcMetAP-I and replacing a water ligand. Further differences between the binding modes of Co(II) were observed in the dicobalt(II) form of D97E EcMetAP-I. Whereas there was no evidence for significant exchange coupling in spectra obtained for wild-type EcMetAP-I, the spectrum of [CoCo(D97E EcMetAP-I)] (Fig. 6D) exhibited a feature at geff ~ 12 that was suggestive of an integer spin system with S′ = 3. Subtraction of the [Co_(D97E EcMetAP-I)] spectrum and the wild-type spectrum yielded a difference spectrum (Fig. 6E) with similarities to integer spin signals observed in other dicobalt(II) systems [33], and the parallel mode EPR signal, with a resonance at geff ~ 11 (Fig. 6F), confirmed that the Co(II) ions in [CoCo(D97E EcMetAP-I)] do indeed form a weakly exchange-coupled dinuclear center.

Close examination of the EPR signal from [Co_(D97N EcMetAP-I)] recorded at 6 K (Fig. 6G) revealed a 59Co hyperfine pattern superimposed on the dominant axial signal, indicating the presence of two species of Co(II). The pattern was centered at geff ~ 7.9 and, interestingly, no other features that could be readily associated with this pattern were evident. It is possible, then, that the hyperfine pattern in the spectrum of [Co_(D97N EcMetAP-I)] is part of an MS = | ± 3/2〉 signal, indicative of tetrahedral character for Co(II) ions, for which the g⊥ features are unobservable at 9.6 GHz. This explanation is also consistent with the loss of the hyperfine pattern upon an increase of the temperature by a mere 2 K; MS = | ±3/2〉 signals are often only observed at temperatures around 5 K, because of rapid relaxation at higher temperatures [34–36]. Despite the superficial similarity of the hyperfine patterns observed in the spectra of [Co_(D97N EcMetAP-I)] and [Co_(D97E EcMetAP-I)], the Co(II) species from which these originate are probably very different. An additional difference between D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I is the lack of evidence for exchange coupling in [CoCo(D97N EcMetAP-I)]; the formation of a spin-coupled dinuclear center appears to be unique to D97E EcMetAP-I.

Discussion

A major stumbling block in the design of small molecule inhibitors of MetAPs centers on how many metal ions are present in the active site under physiological conditions. Most of the X-ray crystallographic data reported for MetAPs indicate that two metal ions form a dinuclear active site [24,37–42]. However, kinetic data suggest that only one metal ion is required for full enzymatic activity, and EXAFS studies on Co(II)-and Fe(II)-loaded EcMetAP-I did not provide any evidence for a dinuclear site [22,23,25,27]. Recently, the X-ray crystal structure of a mono-Mn(II) EcMetAP-I enzyme bound by l-norleucine phosphonate was reported, providing the first crystallographic data for a mononuclear MetAP [24]. Taken together, these data suggest that MetAPs are mononuclear exopeptidases, however, kinetic, MCD and atomic absorption spectrometry data indicate that Co(II) ions bind to EcMetAP-I in a weakly cooperative fashion [26,28]. In order to reconcile these data and determine whether a dinuclear site is required for enzymatic activity, as well as shed some light on the catalytic role of Asp97 in EcMetAP-I, we prepared the D97A, D97E and D97N mutant enzymes. This aspartate is strictly conserved in all MetAPs as well as in other enzymes in the ‘pita-bread’ superfamily (e.g. aminopeptidase P and prolidase) (Fig. 2) [14,16,17,19,21,43–46]. Replacement of this conserved aspartate in human prolidase by asparagine causes skin abnormalities, recurrent infections, and mental retardation [45].

On the basis of ICP-AES analyses, both D97A EcMetAP-I and D82A PfMetAP-II bind only one divalent metal ion tightly, which is identical to what is seen with the wild-type enzyme [22,25]. Therefore, the second metal ion is either not present or is loosely associated. Consistent with ICP-AES analyses, the Kd value determined for D97A EcMetAP-I using ITC indicates the presence of only one tightly bound divalent metal ion, and the Kd1 is not affected as compared to the wild-type enzyme [22,25]. Therefore, the Kd1 value observed for D97A EcMetAP-I appears to correspond to the microscopic binding constant of a single metal ion to the histidine-containing side of the EcMetAP-I active site, consistent with the hypothesis that substitution of Asp97, a residue that functions as the only nonbridging ligand for the second metal-binding site, effectively eliminates the ability of a second divalent metal ion to bind in the active site. For wild-type EcMetAP-I, two additional weak metal-binding events are also observed. Rather than three total observed metal-binding sites, D97A EcMetAP-I binds only two Co(II) ions, the second probably being in a remote Co(II)-binding site identified in the X-ray crystal structure of EcMetAP-I [15,19]. This remote metal-binding site, or third metal-binding site, was also observed in the structure of the type I methionine aminopeptidase from H. sapiens [21]. In both enzymes, this remote site is on the outer edge of the enzyme and becomes at least partially occupied at Co(II) concentrations near 1 mm. Therefore, the second divalent metal-binding event observed via ITC for D97A EcMetAP-I is postulated to be due to the binding of a Co(II) ion to the remote divalent metal-binding site with a Kd2 of 2.2 mm.

ICP-AES data obtained with D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I are also consistent with ITC data, in that only one tightly bound divalent metal ion is present in these enzymes. Interestingly, the ITC data obtained for D97E EcMetAP-I can only be fitted on the assumption of positive cooperativity, similar to that reported by Larrabee et al. for wild-type EcMetAP-I [26]. The enhanced cooperativity observed for D97E versus wild-type EcMetAP-I is probably due to the increased carbon chain length of glutamate versus aspartate, which may adjust the position of the second metal-binding site. Similar to what is seen with wild-type EcMetAP-I, two weak binding events are also observed for D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I, suggesting that a second metal ion can still bind to the dinuclear active site even when the bidentate ligand aspartate is replaced by glutamate or asparagine. However, the ability of D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I to bind a second divalent metal ion increases ~ 60-fold as compared to wild-type EcMetAP-I.

The observed kcat values for D97A EcMetAP-I in the presence of three equivalents of Co(II) at pH 7.5 decreased 6100-fold as compared to the wild-type enzyme. D97N and D97E EcMetAP-I are also slightly active, but neither of these mutant enzymes recover wild-type activity levels. These data are consistent with a previous study on D97A EcMetAP-I, where it was reported that ~ 4% of the residual activity of wild-type EcMetAP-I was retained [47]. On the basis of these data, this strictly conserved aspartate is a catalytically important residue but is not absolutely required for enzymatic activity. The fact that catalytic activity is observed for both D97A EcMetAP-I and D82A PfMetAP-II, enzymes in which the second divalent metal-binding site has probably been eliminated, suggests that MetAP enzymes can function as mononuclear enzymes. Interestingly, the observed Km value for D97A EcMetAP-I, which is a partial indicator of the affinity of an enzyme for its substrate, decreased by ~ 2.7-fold, suggesting that D97A EcMetAP-I binds MGMM more tightly than the wild-type enzyme. The combination of these data provides a catalytic efficiency for D97A EcMetAP-I that is ~ 4000-fold poorer than that of wild-type EcMetAP-I. This result is significant in light of the evidence that metal binding to D97A EcMetAP-I is probably not cooperative and dinuclear sites do not appear to form.

Further insight into the structure–function relationships of the metal-binding sites of EcMetAP-I comes from electronic absorption and EPR spectroscopy. The Co(II) d–d spectra for wild-type, D97E and D97A EcMetAP-I exhibited very little difference in form, in each case, between the monocobalt(II) and dicobalt(II) forms, and only a doubling of intensity was observed upon addition of a second Co(II) ion. For wild-type and D97A EcMetAP-I, this was reflected in the EPR spectra, which also did not differ significantly between the monocobalt(II) and dicobalt(II) forms. In contrast, the electronic absorption spectra of [Co_(D97N EcMetAP-I)] and [CoCo(D97N EcMetAP-I)] are distinct, as are the EPR spectra. On the basis of the observed molar absorptivities, the Co(II) ions binding to the D97E, D97A and D97N EcMetAP-I active sites are pentacoordinate [48] and, apart from a putative tetrahedral species implied by a minor component of the EPR spectrum of [Co_(D97N EcMetAP-I)], the EPR spectra are all consistent with this interpretation, with high axial symmetry being seen in D97A and D97N EcMetAP-I. The minor component in D97N EcMetAP-I that is tentatively assigned as a tetrahedral Co(II) may be in equilibrium (in solution) with the dominant five-coordinate form, and the EPR signal due to this species was not exhibited by the dicobalt(II) form of D97N EcMetAP-I. This, in turn, suggests that rearrangement of the active site upon binding a second Co(II) ion leads to a preference for the higher coordination geometry, perhaps due to stabilization of a hitherto weakly bound water ligand by either bridging the two Co(II) ions or via hydrogen bonding.

EPR spectra obtained for D97E EcMetAP-I are particularly interesting, and indicate: (a) a much more distorted five-coordinate geometry for the first Co(II) ion with a much more rigid ligand complement, which probably lacks a solvent ligand; and (b) the formation of a weakly exchange-coupled bona fide dinuclear site upon the addition of two Co(II) ions. Taken together, the EPR data obtained for D97E EcMetAP-I suggest that the loss of aspartate at position 97 is not responsible for the observed change in the Co(II) environment of the M1 site, but rather the presence of the glutamate side chain. It is tempting to speculate that Glu97 provides one or more ligands to the first Co(II)-binding site, and indeed bidentate binding of Glu97 may prevent binding of the solvent ligand that appears to be present in other mono-cobalt(II) species of EcMetAP-I.

Combination of these data suggests that mutating the only nonbridging ligand in the second divalent metal-binding site in MetAPs to an alanine, which effectively removes the ability of the enzyme to form a dinuclear site, provides a MetAP enzyme that retains catalytic activity, albeit at extremely low levels. Reconciliation of these data with kinetic, ITC, crystallographic and EXAFS data suggesting that MetAPs are mononuclear with kinetic, MCD and EPR data indicating that metal binding is cooperative, at first glance, appears to be tricky [22,24,26,29,30]. However, the most logical explanation leads to the conclusion that metal binding to MetAPs is cooperative, and that discrepancies have arisen due to the concentrations of the enzyme samples used in the various experiments. For example, ITC data do not reveal cooperative binding for divalent metal ions to EcMetAP-I or PfMetAP-II but, instead, indicate that one metal ion binds with much higher affinity than subsequent metal ions. It should be noted that ITC titrations are typically run with enzyme concentrations of 70 µm, and most often reveal two sets of binding sites, similar to that observed for D97N EcMetAP-I [22]. Likewise, initial activity assays carried out on EcMetAP-I and PfMetAP-II used an enzyme concentration of 20 µm, which is two orders of magnitude larger than the Kd value determined for the first metal-binding site of 0.2 or 0.4 µm, assuming Hill coefficients of 1.3 or 2.1, respectively [26,28]. However, a Kd value of between 2.5 and 4.0 µm was reported if it was assumed that only a single Co(II)-binding site exists in the low-concentration regime, which is within the error of ITC and kinetic Kd values. Spectroscopic and most X-ray crystallographic measurements were carried out at much higher enzyme (~ 1 mm) and metal concentrations, where a significant concentration of dinuclear sites will undoubtedly be present. Under the conditions utilized in ITC experiments, any cooperativity in divalent metal binding will not be detectable, but may appear in EPR and electronic absorption data. As activity titrations and ITC data are not particularly sensitive to the type of binding (i.e. cooperativity versus two independent binding sites), the weak cooperativity observed by Larrabee et al. [26] will not be observed in these experiments but is entirely consistent with the EPR and electronic absorption data and, indeed, with recent X-ray crystallographic data. Most X-ray structures of MetAPs were determined with a large excess of divalent metal ions, so only dinuclear sites were observed. However, crystallographic data obtained on EcMetAP-I using metal ion / enzyme ratios of 0.5 : 1 reveal metal ion occupancies of 71% bound to the M1 site and 28% bound to the M2 site, consistent with cooperative binding [24].

In conclusion, mutating the only nonbridging ligand in the second divalent metal-binding site in MetAPs to an alanine, which effectively removes the ability of the enzyme to form a dinuclear site, provides MetAPs that retain catalytic activity, albeit at extremely low levels. Although mononuclear MetAPs are active, the physiologically relevant form of the enzyme is probably dinuclear, given that the majority of the data reported to date are consistent with weak cooperative binding. Therefore, Asp97 primarily functions as a ligand for the second divalent metal-binding site, but also probably assists in binding and positioning the substrate through interactions with the N-terminal amine. The data reported herein highlight the complexity of the active site of EcMetAP-I, and provide additional insights into the role that active site residues play in the hydrolysis of peptides by MetAPs as well as aminopeptidase P and prolidase.

Experimental procedures

Mutagenesis, protein expression and purification

Altered forms of EcMetAP-I were obtained by PCR mutagenesis using the following primers: 5′-GGC GAT ATC GTT AAC ATT XXX GTC ACC GTA ATC AAA GAT GG-3′ and 5′-CCA TCT TTG ATT ACG GTG AC YYY A ATG TTA ACG ATA TCG CC-3′, with XXX standing for GCT, AAT, or GAG, and YYY standing for AGC, TTA, or CTC, of EcMetAP-I D97A, D97N and D97E. Site-directed mutants were obtained using the Quick Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), following Stratagene’s procedure. Reaction products were transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue competent cells (recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔ M15 Tn10(Tetr)]), grown on LB agar plates containing kanamycin at a concentration of 50 µg·mL−1. A single colony of each mutant was grown in 50 mL of LB containing 50 µg·mL−1 kanamycin. Plasmids were isolated using Wizard Plus Miniprep DNA purification kits (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) or Qiaprep Spin Miniprep kits (Qiagene, Valencia, CA, USA). Each mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing (USU Biotechnology Center). Plasmids containing the altered EcMetAP-I genes were transformed into E. coli BL21 Star(DE3) [F− ompT hsdSB (rB −mB −) gal dcm rne131 (DE3)] (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and stock cultures were prepared. The variants were purified in an identical manner to the wild-type enzyme [15,31]. Purified variants exhibited a single band on SDS /PAGE at an Mr of 29 630. Protein concentrations were estimated from the absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 16 445 m−1·cm−1 [12,18]. Apo-EcMetAP-I was washed free of methionine using Chelex-100-treated methionine-free buffer (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mm KCl) and concentrated by microfil-tration using a Centricon-10 (Amicon, Beverly, MA, USA) prior to all kinetic assays. Individual aliquots of apo-EcMetAP-I were routinely stored at −80 °C or in liquid nitrogen until needed. Similarly, we also prepared D82E, D82N and D82A PfMetAP-II and purified them to homogeneity, according to SDS /PAGE analysis.

Metal content measurements

Mutated EcMetAP-I enzyme samples prepared for metal analysis were typically 30 µm. Apo-EcMetAP-I samples were incubated anaerobically with MCl2, where M = Co(II), for 30 min prior to exhaustive anaerobic exchange into Chelex-100-treated buffer as previously reported [31]. Metal analyses were performed using ICP-AES.

Enzymatic assay of EcMetAP-I enzymes

All enzymatic assays were performed under strict anaerobic conditions in an inert atmosphere glove box (Coy) with a dry bath incubator to maintain the temperature at 30 °C. Catalytic activities were determined with an error of ± 5%. Enzyme activities for each mutated enzyme were determined in 25 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.5) containing 150 mm KCl with the tetrapeptide substrate MGMM. The amount of product formation was determined by HPLC (Shimadzu LC-10A class-VP5). A typical assay involved the addition of 8 µL of metal-loaded EcMetAP-I enzyme to a 32 µL substrate–buffer mixture at 30 °C for 1 min. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 40 µL of a 1% trifluoroacetic acid solution. Elution of the product was monitored at 215 nm following separation on a C8 HPLC column (Phenomenex, Luna; 5 µm, 4.6 × 25 cm), as previously described [22,31]. Enzyme activities are expressed as units per milligram, where one unit is defined as the amount of enzyme that releases 1 µmol of product in 1 min at 30 °C.

ITC

ITC measurements were carried out on a MicroCal OMEGA ultrasensitive titration calorimeter. The titrant (CoCl2) and apo-EcMetAP-I solutions of the mutated enzymes were prepared in Chelex-100-treated 25 mm Hepes buffer at pH 7.5, containing 150 mm KCl. Stock buffer solutions were thoroughly degassed before each titration. The enzyme solution (70 µm) was placed in the calorimeter cell and stirred at 200 r.p.m. to ensure rapid mixing. Typically, 3 µL of titrant was delivered over 7.6 s with a 5-min interval between injections to allow for complete equilibration. Each titration was continued until 4.5–6 eq. of Co(II) had been added, to ensure that no additional complexes were formed in excess titrant. A background titration, consisting of the identical titrant solution but only the buffer solution in the sample cell, was subtracted from each experimental titration to account for heat of dilution. These data were analyzed with a two- or three-site binding model by the Windows-based origin software package supplied by MicroCal [49].

Spectroscopic measurements

Electronic absorption spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-3101PC spectrophotometer. All variant apo-EcMetAP-I samples used in spectroscopic measurements were made rigorously anaerobic prior to incubation with Co(II) (CoCl2, ≥ 99.999%; Strem Chemicals, Newburyport, MA) for ~ 30 min at 25 °C. Co(II)-containing samples were handled throughout in an anaerobic glove box (Ar /5% H2, ≤ 1 p.p.m. O2; Coy Laboratories) until frozen. Electronic absorption spectra were normalized for the protein concentration and the absorption due to uncomplexed Co(II) (ε512 nm = 6.0 m−1·cm−1) [22]. Low-temperature EPR spectroscopy was performed using either a Bruker ESP-300E or a Bruker EleXsys spectrometer equipped with an ER 4116 DM dual mode X-band cavity and an Oxford Instruments ESR-900 helium flow cryostat. Background spectra recorded on a buffer sample were aligned with and subtracted from experimental spectra as in earlier work [33,50]. EPR spectra were recorded at microwave frequencies of approximately 9.65 GHz: precise microwave frequencies were recorded for individual spectra to ensure precise g-alignment. All spectra were recorded at 100 kHz modulation frequency. Other EPR running parameters are specified in the figure legends for individual samples. EPR simulations were carried out using matrix diagonalization (xsophe, Bruker Biospin), assuming a spin Hamiltonian H = βgHS + SDS + SAI, with S = 3/ 2 and D > βgHS (= hν). Enzyme concentrations for EPR were 1 mm. Mutated enzyme samples for EPR were frozen after incubation with the appropriate amount of Co(II) for 60 min at 25 °C.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0652981, R. C. Holz) and the National Institutes of Health (AI056231, B. Bennett). The Bruker Elexsys spectrometer was purchased by the Medical College of Wisconsin and is supported with funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH, EB001980, B. Bennett).

Abbreviations

- EcMetAP-I

type I methionine aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli

- eq.

equivalent

- EXAFS

extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy

- ICP-AES

inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy

- ITC

isothermal calorimetry

- MCD

magnetic CD

- MGMM

Met-Gly-Met-Met

- PfMetAP-II

type II methionine aminopeptidase from Pyrococcus furiosus

References

- 1.Bradshaw RA. Protein translocation and turnover in eukaryotic cells. TIBS. 1989;14:276–279. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meinnel T, Mechulam Y, Blanquet S. Methionine as translation start signal – a review of the enzymes of the pathway in Escherichia coli. Biochimie. 1993;75:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90005-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradshaw RA, Brickey WW, Walker KW. N-terminal processing: the methionine aminopeptidase and Nα-acetyl transferase families. TIBS. 1998;23:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arfin SM, Bradshaw RA. Cotranslational processing and protein turnover in eukaryotic cells. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7979–7984. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowther WT, Matthews BW. Metalloamino-peptidases: common functional themes in disparate structural surroundings. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4581–4607. doi: 10.1021/cr0101757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowther WT, Matthews BW. Structure and function of the methionine aminopeptidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang S-YP, McGary EC, Chang S. Methionine aminopeptidase gene of Escherichia coli is essential for cell growth. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4071–4072. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.4071-4072.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang Y-H, Teichert U, Smith JA. Molecular cloning, sequencing, deletion, and overexpression of a methionine aminopeptidase gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8007–8011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Chang Y-H. Amino terminal protein processing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an essential function that requires two distinct methionine aminopeptidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12357–12361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller CG, Kukral AM, Miller JL, Movva NR. pepM is an essential gene in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5215–5217. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5215-5217.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taunton J. How to starve a tumor. Chem Biol. 1997;4:493–496. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith EC, Su Z, Turk BE, Chen S, Chang Y-H, Wu Z, Biemann K, Liu JO. Methionine aminopeptidase (type 2) is the common target for angiogenesis inhibitors AGM-1470 and ovalicin. Chem Biol. 1997;4:461–471. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sin N, Meng L, Wang MQ, Wen JJ, Bornmann WG, Crews CM. The anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin covalently binds and inhibits the methionine aminopeptidase, MetAP-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6099–6103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Widom J, Kemp CW, Crews CM, Clardy J. Structure of the human methionine aminopeptidase-2 complexed with fumagillin. Science. 1998;282:1324–1327. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowther WT, McMillen DA, Orville AM, Matthews BW. The anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin covalently modifies a conserved active site histidine in the Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12153–12157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douangamath A, Dale GE, D’Arcy A, Almstetter M, Eckl R, Frutos-Hoener A, Henkel B, Illgen K, Nerdinger S, Schulz H, et al. Crystal structures of Staphylococcus aureus methionine aminopeptidase complexed with keto heterocycle and aminoketone inhibitors reveal the formation of a tetrahedral intermediate. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1325–1328. doi: 10.1021/jm034188j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tahirov TH, Oki H, Tsukihara T, Ogasahara K, Yutani K, Ogata K, Izu Y, Tsunasawa S, Kato I. Crystal structure of the methionine aminopeptidase from the hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus furiosus. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:101–124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowther WT, Orville AM, Madden DT, Lim S, Rich DH, Matthews BW. Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase: implications of crystallographic analyses of the native, mutant and inhibited enzymes for the mechanism of catalysis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7678–7688. doi: 10.1021/bi990684r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roderick LS, Matthews BW. Structure of the cobalt-dependent methionine aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli: a new type of proteolytic enzyme. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3907–3912. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spraggon G, Schwarzenbacher R, Kreusch A, McMullan D, Brinen LS, Canaves JM, Dai X, Deacon AM, Elsliger MA, Eshagi S, et al. Crystal structure of a methionine aminopeptidase (TM1478) from Thermotoga maritima at 1.9 Ǻ resolution. Proteins. 2004;56:396–400. doi: 10.1002/prot.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addlagatta A, Hu X, Liu JO, Matthews BW. Structural basis for the functional differences between type I and type II human methionine aminopeptidases. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14741–14749. doi: 10.1021/bi051691k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Souza VM, Bennett B, Copik AJ, Holz RC. Characterization of the divalent metal binding properties of the methionyl aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3817–3826. doi: 10.1021/bi9925827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosper NJ, D’Souza V, Scott R, Holz RC. Structural evidence that the methionyl aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli is a mononuclear metalloprotease. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13302–13309. doi: 10.1021/bi010837m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye QZ, Xie SX, Ma ZQ, Huang M, Hanzlik RP. Structural basis of catalysis by monometalated methionine aminopeptidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9470–9475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602433103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng L, Ruebush S, D’Souza VM, Copik AJ, Tsunasawa S, Holz RC. Overexpression and divalent metal binding studies for the methionyl aminopeptidase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7199–7208. doi: 10.1021/bi020138p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larrabee JA, Leung CH, Moore R, Thamrong-nawasawat T, Wessler BH. Magnetic circular dichroism and cobalt(II) binding equilibrium studies of Escherichia coli methionyl aminopeptidase. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12316–12324. doi: 10.1021/ja0485006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Sheppard GS, Lou P, Kawai M, Park C, Egan DA, Schneider A, Bouska J, Lesniewski R, Henkin J. Physiologically relevant metal cofactor for methionine aminopeptidase-2 is manganese. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5035–5042. doi: 10.1021/bi020670c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu XV, Chen X, Han KC, Mildvan AS, Liu JO. Kinetic and mutational studies of the number of interacting divalent cations required by bacterial and human methionine aminopeptidases. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12833–12843. doi: 10.1021/bi701127x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Copik AJ, Nocek B, Swierczek SI, Ruebush S, SeBok J, D’Souza VM, Peters J, Bennett B, Holz RC. EPR and X-ray crystallographic characterization of the product bound form of the Mn(II)-loaded methionyl aminopeptidase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochemistry. 2005;44:121–129. doi: 10.1021/bi048123+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Souza VM, Brown RS, Bennett B, Holz RC. Charaterization of the active site and insight into the binding mode of the anti-angiogenesis agent fumagillin to the Mn(II)-loaded methionyl aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2005;10:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Souza VM, Holz RC. The methionyl aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli is an iron(II) containing enzyme. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11079–11085. doi: 10.1021/bi990872h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winzor DJ, Sawyer WH. Quantitative Characterization of Ligand Binding. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett B, Holz RC. EPR studies on the mono- and dicobalt(II)-substituted forms of the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica. Insight into the catalytic mechanism of dinuclear hydrolases. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1923–1933. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huntington KM, Bienvenue D, Wei Y, Bennett B, Holz RC, Pei D. Slow-binding inhibition of the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica by peptide thiols: synthesis and spectral characterization. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15587–15596. doi: 10.1021/bi991283e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bienvenue D, Bennett B, Holz RC. Inhibition of the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica by L-leucinethiol: kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of a slow, tight-binding inhibitor–enzyme complex. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;78:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crawford PA, Yang K-W, Sharma N, Bennett B, Crowder MW. Spectroscopic studies on cobalt(II)-substituted metallo-β-lactamase ImiS from Aeromonas veronii bν sobria. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5168–5176. doi: 10.1021/bi047463s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vallee BL, Auld DS. Cocatalytic zinc motifs in enzyme catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2715–2718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vallee BL, Auld DS. New perspective on zinc biochemistry: cocatalytic sites in multi-zinc enzymes. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6493–6500. doi: 10.1021/bi00077a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipscomb WN, Sträter N. Recent advances in zinc enzymology. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2375–2433. doi: 10.1021/cr950042j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dismukes GC. Manganese enzymes with binuclear active sites. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2909–2926. doi: 10.1021/cr950053c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sträter N, Lipscomb WN, Klabunde T, Krebs B. Two-metal ion catalysis in enzymatic acyl- and phosphoryl-transfer reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:2024–2055. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilcox DE. Binuclear metallohydrolases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2435–2458. doi: 10.1021/cr950043b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bazan JF, Weaver LH, Roderick SL, Huber R, Matthews BW. Sequence and structure comparison suggest that methionine aminopeptidase, prolidase, aminopeptidase-P, and creatinase share a common fold. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2473–2477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oefner C, Douangamath A, D’Arcy AHS, Mareque D, MacSweeney A, Padilla J, Pierau S, Schulz H, Thormann M, Wadman S, et al. The 1.15 Ǻ crystal structure of the Staphylococcus aureus methionyl aminopeptidase and complexes with triazole based inhibitors. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00862-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maher MJ, Ghosh M, Grunden AM, Menon AL, Adams MW, Freeman HC, Guss JM. Structure of the prolidase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2771–2783. doi: 10.1021/bi0356451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilce MCJ, Bond CS, Dixon NE, Freeman HC, Guss JM, Lilley PE, Wilce JA. Structure and mechanism of a proline-specific aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3472–3477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiu C-H, Lee C-Z, Lin K-S, Tam MF, Lin L-Y. Amino acid residues involved in the functional integrity of the Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4686–4689. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4686-4689.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertini I, Luchinat C. High-spin cobalt(II) as a probe for the investigation of metalloproteins. Adv Inorg Biochem. 1984;6:71–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Copik AJ, Swierczek SI, Lowther WT, D’Souza V, Matthews BW, Holz RC. Kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of the H178A mutant of the methionyl aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6283–6292. doi: 10.1021/bi027327s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bennett B, Holz RC. Spectroscopically distinct cobalt(II) sites in heterodimetallic forms of the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica: characterization of substrate binding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9837–9846. doi: 10.1021/bi970735p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]