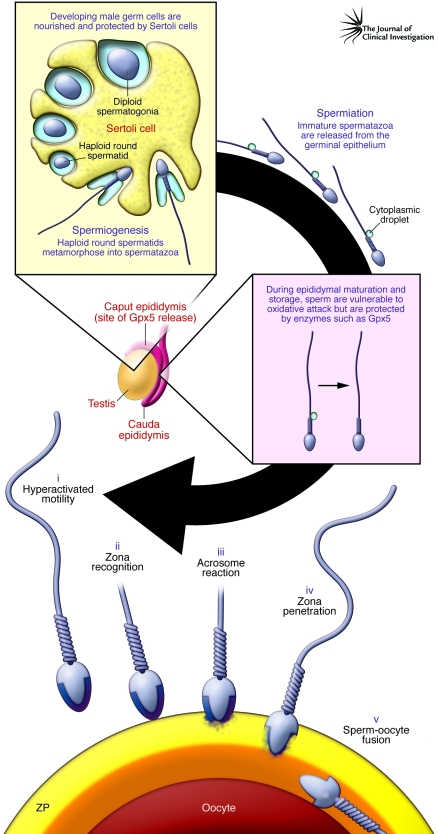

Figure 1. A simplified life history of mammalian spermatozoa.

Male germ cells differentiate in the germinal epithelium, nourished and protected by the nurse cells of the testes, Sertoli cells. Spermatozoa emerge from meiosis as a syncytium of small round spermatids that, in the absence of de novo gene transcription, undergo one of the most dramatic transformations in biology, as they engage in a process known as spermiogenesis and transform into spermatozoa. Once spermiogenesis has been completed, spermatozoa leave the germinal epithelium structurally complete (apart from a cytoplasmic droplet in the sperm midpiece) but lacking in functional competence. The potential to express movement and fertilize the oocyte is acquired during epididymal transit. Spermatozoa are then stored in a quiescent state in the cauda epididymis, ready for ejaculation and subsequent capacitation in the female tract. As a result of capacitation, spermatozoa realize the range of functions acquired as a result of epididymal maturation, including (i) hyperactivated motility, (ii) zona recognition, (iii) the acrosome reaction, (iv) zona penetration, and (v) sperm-oocyte fusion. Throughout their maturation in the epididymis, the spermatozoa exist as isolated cells that are vulnerable to oxidative attack. Because they lack substantial intrinsic defense mechanisms, these cells are highly dependent on extracellular antioxidants released into the epididymal lumen. Prominent among the complex array of antioxidant enzymes present in epididymal plasma is Gpx5. In this issue of the JCI, Chabory et al. (7) report that deletion of Gpx5 in male mice generates a state of oxidative stress within the epididymis that becomes particularly marked with age and is associated with both miscarriage and developmental defects in the embryos. ZP, zona pellucida.