Abstract

Background

Anxiety disorders are common psychiatric conditions affecting children and adolescents. Although cognitive behavioral therapy and selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors have shown efficacy in treating these disorders, little is known about their relative or combined efficacy.

Methods

In this randomized, controlled trial, we assigned 488 children between the ages of 7 and 17 years who had a primary diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or social phobia to receive 14 sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline (at a dose of up to 200 mg per day), a combination of sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy, or a placebo drug for 12 weeks in a 2:2:2:1 ratio. We administered categorical and dimensional ratings of anxiety severity and impairment at baseline and at weeks 4, 8, and 12.

Results

The percentages of children who were rated as very much or much improved on the Clinician Global Impression-Improvement scale were 80.7% for combination therapy (P<0.001), 59.7% for cognitive behavioral therapy (P<0.001), and 54.9% for sertraline (P<0.001); all therapies were superior to placebo (23.7%). Combination therapy was superior to both monotherapies (P<0.001). Results on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale documented a similar magnitude and pattern of response; combination therapy had a greater response than cognitive behavioral therapy, which was equivalent to sertraline, and all therapies were superior to placebo. Adverse events, including suicidal and homicidal ideation, were no more frequent in the sertraline group than in the placebo group. No child attempted suicide. There was less insomnia, fatigue, sedation, and restlessness associated with cognitive behavioral therapy than with sertraline.

Conclusions

Both cognitive behavioral therapy and sertraline reduced the severity of anxiety in children with anxiety disorders; a combination of the two therapies had a superior response rate. (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00052078.)

Anxiety disorders are common in children and cause substantial impairment in school, in family relationships, and in social functioning.1,2 Such disorders also predict adult anxiety disorders and major depression.3-6 Despite a high prevalence (10 to 20%3,7,8) and substantial morbidity, anxiety disorders in childhood remain underrecognized and undertreated.1,9 An improvement in outcomes for children with anxiety disorders would have important public health implications.

In clinical trials, separation and generalized anxiety disorders and social phobia are often grouped together because of the high degree of overlap in symptoms and the distinction from other anxiety disorders (e.g., obsessive-compulsive disorder). Efficacious treatments for these disorders include cognitive behavioral therapy10,11 and the use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).12,13 However, randomized, controlled trials comparing cognitive behavioral therapy, the use of an SSRI, or the combination of both therapies with a control are lacking. The evaluation of combination therapy is particularly important because approximately 40 to 50% of children with these disorders do not have a response to short-term treatment with either monotherapy.14,15

Our study, called the Child-Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study, was designed to address the current gaps in the treatment literature by evaluating the relative efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, a combination of the two therapies, and a placebo drug. This article reports the results of short-term treatment.

Methods

Study Design and Implementation

This study was designed as a two-phase, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial for children and adolescents between the ages of 7 and 17 years who had separation or generalized anxiety disorder or social phobia. Phase 1 was a 12-week trial of short-term treatment comparing cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, and their combination with a placebo drug. Phase 2 is a 6-month open extension for patients who had a response in phase 1.

The authors designed the study, wrote the manuscript, and vouch for the data gathering and analysis. Pfizer provided sertraline and matching placebo free of charge but was not involved in the design or implementation of the study, the analysis or interpretation of data, the preparation or review of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results of the study.

Study Subjects

Children between the ages of 7 and 17 years with a primary diagnosis of separation or generalized anxiety disorder or social phobia (according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision [DSM-IV-TR]16), substantial impairment, and an IQ of 80 or more were eligible to participate. Children with coexisting psychiatric diagnoses of lesser severity than the three target disorders were also allowed to participate; such diagnoses included attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) while receiving stable doses of stimulant and obsessive-compulsive, post-traumatic stress, oppositional-defiant, and conduct disorders. Children were excluded if they had an unstable medical condition, were refusing to attend school because of anxiety, or had tried but had not had a response to two adequate trials of SSRIs or an adequate trial of cognitive behavioral therapy. Girls who were pregnant or were sexually active and were not using an effective method of birth control were also excluded. Children who were receiving psychoactive medications other than stable doses of stimulants and who had psychiatric diagnoses that made participation in the study clinically inappropriate (i.e., current major depressive or substance-use disorder; unmedicated ADHD, combined type; or a lifetime history of bipolar, psychotic, or pervasive developmental disorders) or who presented an acute risk to themselves or others were also excluded.

Recruitment occurred from December 2002 through May 2007 at Duke University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute-Columbia University Medical Center-New York University, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Temple University, University of California, Los Angeles, and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic-University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The protocol was approved and monitored by institutional review boards at each center and by the data and safety monitoring board of the National Institute of Mental Health. Subjects and at least one parent provided written informed consent.

Interventions

Cognitive behavioral therapy involved fourteen 60-minute sessions, which included review and ratings of the severity of subjects’ anxiety, response to treatment, and adverse events. Therapy was based on the Coping Cat program,17,18 which was adapted for the subjects’ age and the duration of the study.19 Each subject who was assigned to receive cognitive behavioral therapy received training in anxiety-management skills, followed by behavioral exposure to anxiety-provoking situations. Parents attended weekly check-ins and two parent-only sessions. Experienced psychotherapists, certified in the Coping Cat protocol, received regular site-level and cross-site supervision.

Pharmacotherapy involved eight sessions of 30 to 60 minutes each that included review and ratings of the severity of subjects’ anxiety, their response to treatment, and adverse events. Sertraline (Zoloft) and matching placebo were administered on a fixed-flexible schedule beginning with 25 mg per day and adjusted up to 200 mg per day by week 8. Through week 8, subjects who were considered to be mildly ill or worse and who had minimal side effects were eligible for dose increases. Psychiatrists and nurse clinicians with experience in medicating children with anxiety disorders were certified in the study pharmacotherapy protocol and received regular site-level and cross-site supervision. Pill counts and medication diaries were used to facilitate and document adherence.

Combination therapy consisted of the administration of sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy. Whenever possible, therapy and medication sessions occurred on the same day for the convenience of subjects.

Objectives

Study objectives were, first, to compare the relative efficacy of the three active treatments with placebo; second, to compare combination therapy with either sertraline or cognitive behavioral therapy alone; and third, to assess the safety and tolerability of sertraline, as compared with placebo. We hypothesized that all three active treatments would be superior to placebo and that combination therapy would be superior to either sertraline or cognitive behavioral therapy alone.

Outcome Assessments

We obtained demographic information, information on symptoms of anxiety, and data on coexisting disorders and psychosocial functioning using reports from both the subjects and their parents and from interviews of subjects and parents at the time of screening, at baseline, and at weeks 4, 8, and 12. The interviews were administered by independent evaluators who were unaware of study-group assignments.

We used the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-TR, Child Version,20 to establish diagnostic eligibility. The categorical primary outcome was the treatment response at week 12, which was defined as a score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale,21 which ranges from 1 to 7, with lower scores indicating more improvement, as compared with baseline. A score of 1 or 2 reflects a substantial, clinically meaningful improvement in anxiety severity. The dimensional primary outcome was anxiety severity as measured on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, computed by the summation of six items assessing anxiety severity, frequency, distress, avoidance, and interference during the previous week.22 Total scores on this scale range from 0 to 30, with scores above 13 indicating clinically meaningful anxiety. The Children’s Global Assessment Scale23 was used to rate overall impairment. Scores on this scale range from 1 to 100; scores of 60 or lower are considered to indicate a need for treatment, and a score of 50 corresponds to moderate impairment that affects most life situations and is readily observable. Agreement among the raters was high for anxiety severity (r=0.85) and diagnostic status (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.82 to 0.88) on the basis of a videotaped review of 10% of assessments by independent evaluators that were performed at baseline and at week 12.

Adverse Events

Adverse events were defined as any unfavorable change in the subjects’ pretreatment condition, regardless of its relationship to a particular therapy. Serious adverse events were life-threatening events, hospitalization, or events leading to major incapacity. Harm-related adverse events were defined as thoughts of harm to self or others or related behaviors.

All subjects were interviewed at the start of each visit by the study coordinator with the use of a standardized script. Identified adverse events and harm-related events were then evaluated and rated by each subject’s study clinician. This report presents data on all serious adverse events, all harm-related adverse events, and moderate and severe (i.e., functionally impairing) adverse events that occurred in 3% or more of subjects in any study group. The data and safety monitoring board of the National Institute of Mental Health performed a quarterly review of reported adverse events.

Given the greater number of study visits (and hence more reporting opportunities) and the unblinded administration of sertraline in the combination-therapy group, the test of the adverse-event profile of sertraline focused on statistical comparisons between sertraline and placebo and sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Randomization and Masking

The randomization sequence in a 2:2:2:1 ratio was determined by a computer-generated algorithm and maintained by the central pharmacy, with stratification according to age, sex, and study center. Subjects were assigned to study groups after being deemed eligible and undergoing verbal reconsent with a study investigator. Subjects in the sertraline and placebo groups did not know whether they were receiving active therapy, nor did their clinicians. However, subjects who received combination therapy knew they were receiving active sertraline. The study protocol called for independent evaluators who completed assessments to be unaware of all treatment assignments.

Statistical Analysis

On the basis of previous studies,10-15 we hypothesized that 80% of children in the combination-therapy group, 60% in either the sertraline group or the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group, and 30% in the placebo group would be considered to have had a response to treatment at week 12. We determined that we needed to enroll 136 subjects in each active-treatment group and 70 subjects in the placebo group for the study to have a power of 80% to detect a minimum difference of 17% between any two study groups in the rate of response, assuming an alpha of 0.05 and a two-tailed test with no adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute). For categorical outcomes (including data regarding adverse events), treatments were compared with the use of Pearson’s chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or logistic regression, as appropriate. Logistic-regression models included the study center as a covariate. For dimensional outcomes, linear mixed-effects models (implemented with the use of PROC MIXED) were used to determine predicted mean values at each assessment point (weeks 4, 8, and 12) and to test the study hypotheses with respect to between-group differences at week 12. In each linear mixed-effects model, time and study group were included as fixed effects, with linear and quadratic time and time-by-treatment group interaction terms. Each model also began with a limited number of covariates (e.g., age, sex, and race), followed by backward stepping to identify the best-fitting and most parsimonious model. In all models, random effects included intercept and linear slope terms, and an unstructured covariance was used to account for within-subject correlation over time. All comparisons were planned and tests were two-sided. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The sequential Dunnett test was used to control the overall (familywise) error rate.24

We analyzed data from all subjects according to study group. Sensitivity analyses were performed with the last observation carried forward (LOCF) and multiple imputation assuming missingness at random. Results were similar for the two missing-data methods. We report the results of the LOCF analysis because the response rates were lower and hence provide a more conservative estimate of outcomes.

Results

Subjects

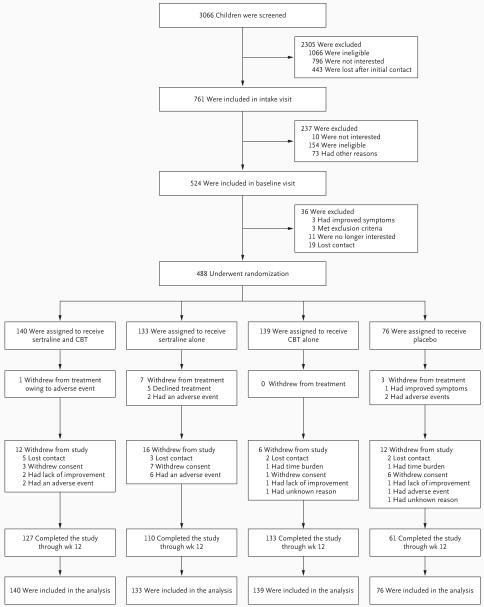

A total of 3066 potentially eligible subjects were screened by telephone (Fig. 1). Of these subjects, 761 signed consent forms and completed the inclusion and exclusion evaluation, 524 were deemed to be eligible and completed the baseline assessment, and 488 underwent randomization. Eleven subjects (2.3%) stopped treatment but were included in the assessment (treatment withdrawals); 46 subjects (9.4%) stopped both treatment and assessment (study withdrawals). On the basis of logistic-regression analyses, pairwise comparisons indicated that subjects in the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group were significantly less likely to withdraw from treatment than were those in the sertraline group (odds ratio, 0.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13 to 0.87; P=0.03) or the placebo group (odds ratio, 0.24; 95% CI; 0.09 to 0.67; P=0.006). Of the 488 subjects who underwent randomization, 459 (94.1%) completed at least one postbaseline assessment, 396 (81.1%) completed all four assessments, and 440 (90.2%) completed the assessment at week 12. Subjects were recruited primarily through advertisements (52.2%) or clinical referrals (44.1%).

Figure 1. Enrollment and Outcomes.

Subjects who are shown as having withdrawn from treatment discontinued their assigned therapy but continued to undergo study assessment. Subjects who are shown as having withdrawn from the study discontinued both therapy and assessment. CBT denotes cognitive behavioral therapy.

Of 14 possible sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy, the mean (±SD) number of sessions completed was 12.7±2.8 in the combination-therapy group and 13.2±2.0 in the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group. The mean dose of sertraline at the final visit was 133.7±59.8 mg per day (range, 25 to 200) in the combination-therapy group, 146.0±60.8 mg per day (range, 25 to 200) in the sertraline group, and 175.8±43.7 mg per day (range, 50 to 200) in the placebo group.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

There were no significant differences among study groups with respect to baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). The mean age of participants was 10.7±2.8 years, with 74.2% under the age of 13 years. There were nearly equal numbers of male and female subjects. Most subjects were white (78.9%), with other racial and ethnic groups represented. Subjects came from predominantly middle-class and upper-middle-class families (74.6%) and lived with both biologic parents (70.3%). Most subjects had received the diagnosis of two or more primary anxiety disorders (78.7%) and one or more secondary disorders (55.3%). At baseline, subjects had moderate-to-severe anxiety and impairment (Table 2). Given the geographic diversity among study centers, there were significant differences among sites on several baseline demographic variables (e.g., race and socioeconomic status). Overall, these variables were equally distributed among study groups within each center; however, three centers had one instance each of unequal distribution for sex, race, or socioeconomic status.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Subjects and Recruitment According to Study Center*

| Variable | Combination Therapy (N=140) | Sertraline (N=133) | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (N=139) | Placebo (N=76) | All Subjects (N=488) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study center — no. (%) | ||||||

| New York State Psychiatric Institute-Columbia University Medical Center-New York University | 18 (12.9) | 15 (11.3) | 16 (11.5) | 10 (13.2) | 59 (12.1) | |

| Duke University Medical Center | 29 (20.7) | 29 (21.8) | 30 (21.6) | 16 (21.1) | 104 (21.3) | |

| Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions | 30 (21.4) | 27 (20.3) | 29 (20.9) | 15 (19.7) | 101 (20.7) | |

| Temple University-University of Pennsylvania | 22 (15.7) | 23 (17.3) | 22 (15.8) | 13 (17.1) | 80 (16.4) | |

| University of California, Los Angeles | 21 (15.0) | 20 (15.0) | 21 (15.1) | 11 (14.5) | 73 (15.0) | |

| Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic-University of Pittsburgh Medical Center | 20 (14.3) | 19 (14.3) | 21 (15.1) | 11 (14.5) | 71 (14.5) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 7-12 yr — no. (%) | 101 (72.1) | 99 (74.4) | 108 (77.7) | 54 (71.1) | 362 (74.2) | 0.66 |

| Mean — yr | 10.7±2.8 | 10.8±2.8 | 10.5±2.9 | 10.6±2.8 | 10.7±2.8 | 0.93 |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 72 (51.4) | 61 (45.9) | 72 (51.8) | 37 (48.7) | 242 (49.6) | 0.75 |

| Race or ethnic group — no. (%)† | 0.43 | |||||

| White | 116 (82.9) | 103 (77.4) | 106 (76.3) | 60 (78.9) | 385 (78.9) | |

| Black | 11 (7.9) | 12 (9.0) | 14 (10.1) | 7 (9.2) | 44 (9.0) | |

| Asian | 6 (4.3) | 4 (3.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) | 12 (2.5) | |

| American Indian | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.2) | 0 | 6 (1.2) | |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Other | 5 (3.6) | 12 (9.0) | 15 (10.8) | 7 (9.2) | 39 (8.0) | |

| Hispanic | 16 (11.4) | 15 (11.3) | 21 (15.1) | 7 (9.2) | 59 (12.1) | 0.59 |

| Low socioeconomic status — no. (%)‡ | 35 (25.0) | 35 (26.3) | 33 (23.7) | 21 (27.6) | 124 (25.4) | 0.92 |

| Primary diagnosis of anxiety disorder — no. (%) | ||||||

| Separation anxiety only | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.8) | 6 (4.3) | 3 (3.9) | 16 (3.3) | 0.53 |

| Social phobia only | 14 (10.0) | 19 (14.3) | 16 (11.5) | 6 (7.9) | 55 (11.3) | 0.51 |

| Generalized anxiety only | 10 (7.1) | 8 (6.0) | 11 (7.9) | 4 (5.3) | 33 (6.8) | 0.87 |

| Separation anxiety and social phobia | 12 (8.6) | 7 (5.3) | 7 (5.0) | 7 (9.2) | 33 (6.8) | 0.46 |

| Separation anxiety and generalized anxiety | 13 (9.3) | 12 (9.0) | 8 (5.8) | 6 (7.9) | 39 (8.0) | 0.69 |

| Social phobia and generalized anxiety | 41 (29.3) | 37 (27.8) | 40 (28.8) | 19 (25.0) | 137 (28.1) | 0.92 |

| Separation anxiety, social phobia, and generalized anxiety | 48 (34.3) | 45 (33.8) | 51 (36.7) | 31 (40.8) | 175 (35.9) | 0.74 |

| Secondary diagnosis of coexisting disorder — no. (%)§ | ||||||

| Other internalizing disorders¶ | 70 (50.0) | 55 (41.4) | 56 (40.3) | 32 (42.1) | 213 (43.6) | 0.35 |

| Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder | 16 (11.4) | 17 (12.8) | 16 (11.5) | 9 (11.8) | 58 (11.9) | 0.98 |

| Oppositional-defiant disorder or conduct disorder | 14 (10.0) | 11 (8.3) | 14 (10.1) | 7 (9.2) | 46 (9.4) | 0.95 |

| Tic disorder | 4 (2.9) | 5 (3.8) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (2.6) | 13 (2.7) | 0.70 |

Plus-minus values are means ±SD.

Race or ethnic group was reported by the subjects.

Low socioeconomic status was defined as a score of 3 or less on the Hollingshead Two-Factor Scale, which ranges from 1 to 5.

Secondary diagnosis of coexisting disorders refers to an allowable diagnosis that was rated as less severe than the anxiety disorder of interest.

Other internalizing disorders include other anxiety disorders and dysthymia.

Table 2.

Key Outcomes at 12 Weeks*

| Assessment Scale and Week of Evaluation | Combination Therapy (N=140) | Sertraline (N=133) | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (N=139) | Placebo (N=76) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale — % with response to therapy (95% CI)† | ||||

| Baseline | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Week 4 | 21.4 (15.4-29.0) | 18.8 (13.0-18.8) | 9.3 (5.5-15.5) | 6.6 (2.6-14.9) |

| Week 8 | 54.3 (46.0-62.3) | 47.4 (39.1-55.8) | 29.5 (22.6-37.6) | 22.4 (14.4-33.1) |

| Week 12 | 80.7 (73.3-86.4) | 54.9 (46.4-63.1) | 59.7 (51.4-67.5) | 23.7 (15.5-34.5) |

| Score on Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale — mean (95% CI)‡§ | ||||

| Baseline | 19.4±3.9 (18.8-20.1) | 18.8±3.9 (18.1-19.4) | 18.9±3.9 (18.2-19.6) | 19.6±3.9 (18.7-20.5) |

| Week 4 | 14.6±3.9 (14.0-15.3) | 14.2±4.0 (13.6-14.9) | 16.0±3.9 (15.4-16.7) | 16.0±4.1 (15.0-16.9) |

| Week 8 | 10.6±4.9 (9.8-11.4) | 11.2±5.0 (10.4-12.1) | 13.3±4.8 (12.5-14.1) | 13.6±5.2 (12.5-14.8) |

| Week 12 | 7.4±6.0 (6.4-8.4) | 9.8±6.2 (8.7-10.8) | 10.8±5.9 (9.8-11.7) | 12.6±6.3 (11.2-14.0) |

| Score on Clinical Globe Impressions-Severity — mean (95% CI)§¶ | ||||

| Baseline | 5.1±0.7 (5.0-5.2) | 5.0±0.7 (4.8-5.1) | 5.0±0.7 (4.9-5.1) | 5.1±0.7 (5.0-5.3) |

| Week 4 | 4.2±0.8 (4.0-4.3) | 4.1±0.8 (4.0-4.2) | 4.5±0.8 (4.4-4.6) | 4.4±0.8 (4.2-4.6) |

| Week 8 | 3.3±1.0 (3.1-3.4) | 3.5±1.0 (3.3-3.6) | 3.9±1.0 (3.7-4.1) | 4.0±1.1 (3.7-4.2) |

| Week 12 | 2.4±1.3 (2.2-2.7) | 3.0±1.3 (2.8-3.2) | 3.3±1.3 (3.1-3.5) | 3.8±1.4 (3.5-4.1) |

| Score on Children’s Global Assessment Scale — mean (95% CI)§∥ | ||||

| Baseline | 50.5±7.0 (49.3-51.7) | 50.9±7.0 (49.7-52.1) | 51.0±7.1 (49.8-52.1) | 50.1±7.0 (48.5-51.6) |

| Week 4 | 56.2±6.7 (55.1-57.4) | 56.8±6.9 (55.6-57.9) | 54.3±6.7 (53.1-55.4) | 54.6±7.0 (53.0-56.2) |

| Week 8 | 62.3±8.3 (60.9-63.6) | 61.4±8.5 (60.0-62.9) | 58.5±8.2 (57.2-59.9) | 58.0±8.7 (56.0-59.9) |

| Week 12 | 68.6±10.4 (66.9-70.3) | 65.0±10.7 (63.1-66.8) | 63.8±10.2 (62.1-65.5) | 60.1±10.9 (57.7-62.6) |

Plus-minus values are means ±SD. All analyses were performed on data from the intention-to-treat population. Primary outcome variables were scores on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale and the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale. NA denotes not applicable.

Values are the proportion of subjects who had a response to therapy, which was defined as a score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale, which ranges from 1 to 7, with lower scores indicating more improvement, as compared with baseline.

Scores on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale range from 0 to 30, with scores higher than 13 consistent with moderate levels of anxiety and a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder.

Values are expected mean scores, which were determined by linear mixed-effects model analysis.

Scores on the Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater severity of the disorder.

Scores on the Children’s Global Assessment Scale range from 1 to 100, with lower scores indicating greater impairment. Scores of 60 or lower are considered to indicate a need for treatment, and a score of 50 corresponds to moderate impairment that affects most life situations and is readily observable.

Clinical Response

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the percentages of children who were rated as 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale at 12 weeks were 80.7% (95% CI, 73.3 to 86.4) in the combination-therapy group, 59.7% (95% CI, 51.4 to 67.5) in the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group, 54.9% (95% CI, 46.4 to 63.1) in the sertraline group, and 23.7% (95% CI, 15.5 to 34.5) in the placebo group (Table 2). With the study center as a covariate, planned pairwise comparisons from a logistic-regression model showed that each active treatment was superior to placebo as follows: combination therapy versus placebo, P<0.001 (odds ratio, 13.6; 95% CI, 6.9 to 26.8); cognitive behavioral therapy versus placebo, P<0.001 (odds ratio, 4.8; 95% CI, 2.6 to 9.0); and sertraline versus placebo, P<0.001 (odds ratio, 3.9; 95% CI, 2.1 to 7.4). Similar pairwise comparisons revealed that combination therapy was superior to either sertraline alone (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% CI, 2.0 to 5.9; P<0.001) or cognitive behavioral therapy alone (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.6 to 4.8; P=0.001). However, there was no significant difference between sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy (P=0.41).

There was no main effect for center (P=0.69); however, a comparison among centers according to study group revealed a significant difference in response to combination therapy but no differences with respect to the response to sertraline alone (P=0.15) or cognitive behavioral therapy alone (P=0.25). Further evaluation of response rates revealed that the average response rate for combination therapy at one center was significantly lower than at the other centers (P=0.002). A sensitivity analysis of site response rates showed that when data from the one site were removed, the average response rate of the other sites was consistent with that of the full sample.

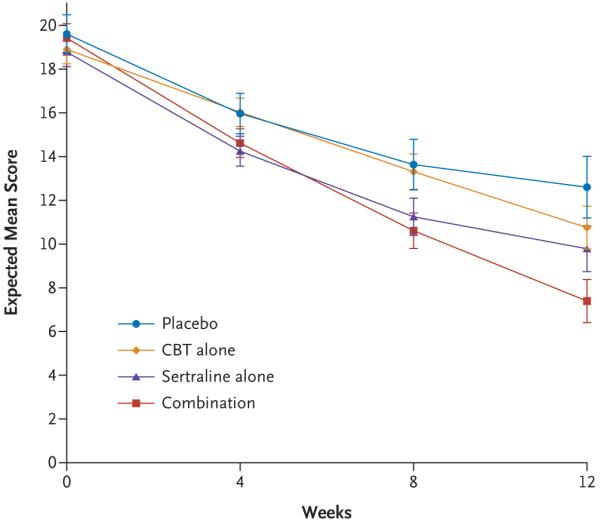

The mixed-effects model for the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale revealed a significant quadratic effect for time (P<0.001) and a significant quadratic time-by-treatment interaction for cognitive behavioral therapy versus placebo (P=0.01) but not for either combination therapy or sertraline versus placebo. In other words, as compared with placebo, cognitive behavioral therapy had a linear mean trajectory (Fig. 2). Planned pairwise comparisons of the expected mean scores on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale at week 12 revealed a similar ordering of outcomes, with all active treatments superior to placebo, according to the following comparisons: combination therapy versus placebo, t=-5.94 (P<0.001); cognitive behavioral therapy versus placebo, t=-2.11 (P=0.04); and sertraline versus placebo, t=-3.15 (P=0.002). In addition, combination therapy was superior to both sertraline alone (t=-3.26, P=0.001) and cognitive behavioral therapy alone (t=-4.73, P<0.001). No significant difference was found between sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy (t=-1.32, P=0.19). The same magnitude and pattern of outcome were found for the Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale and the Children’s Global Assessment Scale.

Figure 2. Scores on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale during the 12-Week Study.

Scores on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale range from 0 to 30, with scores higher than 13 consistent with moderate levels of anxiety and a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. The expected mean score is the mean of the sampling distribution of the mean. The I bars represent standard errors.

Estimates of the effect size (Hedges’ g) and the number needed to treat between the active-treatment groups and the placebo group were calculated. Effect sizes are based on the expected mean scores on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, derived from the mixed-effects model. The number needed to treat is based on the dichotomized, end-of-treatment scores on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale with the use of LOCF. The effect size was 0.86 (95% CI, 0.56 to 1.15) for combination therapy, 0.45 (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.74) for sertraline, and 0.31 (95% CI, 0.02 to 0.59) for cognitive behavioral treatment. The number needed to treat was 1.7 (95% CI, 1.7 to 1.9) for combination therapy, 3.2 (95% CI, 3.2 to 3.5) for sertraline, and 2.8 (95% CI, 2.7 to 3.0) for cognitive behavioral therapy.

Treatment and Study Withdrawals

Most treatment and study withdrawals were attributed to reasons other than adverse events (43 of 57, 75.4%) (Table 3). Of the 14 withdrawals that were attributed to an adverse event, 11 (78.6%) were in the groups receiving either sertraline alone or placebo and consisted of 3 physical events (headache, stomach pains, and tremor) and 8 psychiatric adverse events (worsening of symptoms, 3 subjects; agitation or disinhibition, 3; hyperactivity, 1; and nonsuicidal self-harm and homicidal ideation, 1).

Table 3.

Subjects Who Withdrew from Treatment or the Study*

| Variable | Combination Therapy (N=140) | Sertraline (N=133) | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (N=139) | Placebo (N=76) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| number (percent) | ||||

| Withdrawal from treatment | 1 (0.7) | 7 (5.3) | 0 | 3 (3.9) |

| Attributed to an adverse event | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (2.6) |

| Tremor | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Stomach pain | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Suicidal ideation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Worsening symptoms | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Other reason | 0 | 5 (3.8) | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Improved symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Declined treatment | 0 | 5 (3.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Withdrawal from study | 12 (8.6) | 16 (12.0) | 6 (4.3) | 12 (15.8) |

| Attributed to an adverse event | 2 (1.4) | 6 (4.5) | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Agitation or disinhibition | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Self-harm or homicidal ideation | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperactivity | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Worsening symptoms | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Other reason | 10 (7.1) | 10 (7.5) | 6 (4.3) | 11 (14.5) |

| Lack of improvement | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Loss of contact | 5 (3.6) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (2.6) |

| Time burden | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Withdrawal of consent | 3 (2.1) | 7 (5.3) | 1 (0.7) | 6 (7.9) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) |

Subjects who withdrew from treatment stopped receiving their assigned therapy but continued to undergo assessment; those who withdrew from the study stopped receiving their assigned treatment and did not undergo continued assessment.

Serious Adverse Events

Three subjects had serious adverse events during the study period. One child in the sertraline group had a worsening of behavior that was attributed to the parents’ increased limit setting on avoidance behavior; the event was considered to be possibly related to sertraline. A child in the combination-therapy group had a worsening of preexisting oppositional-defiant behavior that resulted in psychiatric hospitalization; this event was considered to be unrelated to a study treatment. The third subject was hospitalized for a tonsillectomy, which was also considered to be unrelated to a study treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Moderate-to-Severe Adverse Events at 12 Weeks*

| Variable | Combination Therapy (N=140) | Sertraline (N=133) | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (N=139) | Placebo (N=76) | All Subjects (N=488) | P Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sertraline vs. Placebo | Sertraline vs. CBT | ||||||

| number (percent) | |||||||

| Adverse event | |||||||

| Physical | 52 (37.1) | 65 (48.9) | 48 (34.5) | 33 (43.4) | 198 (40.6) | ||

| Headache | 18 (12.9) | 21 (15.8) | 12 (8.6) | 6 (7.9) | 57 (11.7) | 0.10‡ | 0.07‡ |

| Gastric distress | 14 (10.0) | 15 (11.3) | 11 (7.9) | 6 (7.9) | 46 (9.4) | 0.43‡ | 0.35‡ |

| Sore throat | 10 (7.1) | 6 (4.5) | 12 (8.6) | 6 (7.9) | 34 (7.0) | 0.31‡ | 0.17‡ |

| Cold symptoms | 8 (5.7) | 9 (6.8) | 10 (7.2) | 3 (3.9) | 30 (6.1) | 0.54 | 0.89‡ |

| Vomiting | 8 (5.7) | 6 (4.5) | 5 (3.6) | 4 (5.3) | 23 (4.7) | 1.00 | 0.70‡ |

| Insomnia | 7 (5.0) | 11 (8.3)§ | 2 (1.4)§ | 3 (3.9) | 23 (4.7) | 0.23‡ | 0.01‡ |

| Fever | 6 (4.3) | 1 (0.8) | 8 (5.8) | 3 (3.9) | 18 (3.7) | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 5 (3.6) | 3 (2.3) | 7 (5.0) | 3 (3.9) | 18 (3.7) | 0.67 | 0.34 |

| Diarrhea | 6 (4.3) | 5 (3.8) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (2.6) | 17 (3.5) | 1.00 | 0.74 |

| Interrupted sleep | 6 (4.3) | 6 (4.5) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (2.6) | 16 (3.3) | 0.71 | 0.16 |

| Nausea | 5 (3.6) | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (3.9) | 15 (3.1) | 0.71 | 0.72 |

| Body ache | 5 (3.6) | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.6) | 14 (2.9) | 1.00 | 0.72 |

| Fatigue | 3 (2.1) | 8 (6.0)§ | 0§ | 3 (3.9) | 14 (2.9) | 0.75 | 0.003 |

| Accidental injury | 4 (2.9) | 4 (3.0) | 4 (2.9) | 1 (1.3) | 13 (2.7) | 0.66 | 1.00 |

| Allergy | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.6) | 12 (2.5) | 0.63 | 1.00 |

| Asthma | 3 (2.1) | 5 (3.8) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 10 (2.0) | 0.16 | 0.27 |

| Other infection | 5 (3.6) | 0 | 4 (2.9) | 1 (1.3) | 10 (2.0) | 0.36 | 0.12 |

| Ear pain | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 9 (1.8) | 0.54 | 1.00 |

| Sedation | 0 | 6 (4.5)§ | 0§ | 1 (1.3) | 7 (1.4) | 0.43 | 0.01 |

| Psychiatric | 41 (29.3) | 23 (17.3) | 14 (10.1) | 10 (13.2) | 88 (18.0) | ||

| Disinhibition | 12 (8.6) | 6 (4.5) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | 21 (4.3) | 0.43 | 0.16 |

| Increased motor activity | 10 (7.1) | 4 (3.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | 17 (3.5) | 0.66 | 0.44 |

| Disobedient or defiant | 9 (6.4) | 4 (3.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | 16 (3.3) | 0.66 | 0.44 |

| Emotional outburst | 1 (0.7) | 4 (3.0) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (3.9) | 12 (2.5) | 0.71 | 1.00 |

| Restless or fidgety | 5 (3.6) | 5 (3.8)§ | 0§ | 2 (2.6) | 12 (2.5) | 1.00 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety or nervousness | 5 (3.6) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (5.3) | 11 (2.3) | 0.06 | 1.00 |

| Irritability | 3 (2.1) | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.3) | 11 (2.3) | 0.66 | 0.72 |

| Agitation | 7 (5.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 9 (1.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Impulsivity | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) | 9 (1.8) | 1.00 | 0.61 |

| Harm-related¶ | 14 (10.0) | 3 (2.3) | 8 (5.8) | 1 (1.3) | 26 (5.3) | ||

| Aggression | 8 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 11 (2.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-harm behavior without Suicidal intent | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 4 (0.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Suicidal ideation | 5 (3.6) | 0 | 5 (3.6) | 1 (1.3) | 11 (2.3) | 0.36 | 0.06 |

| Suicide attempt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Homicidal ideation | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0.54 | 0.24 |

| Homicide attempt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Serious adverse event¶ | |||||||

| Psychiatric hospitalization | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8)∥ | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medical hospitalization | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Adverse events that occurred in at least 3% of the patients in any study group are reported, unless otherwise noted. Subjects could have more than one adverse event. Case definitions of psychiatric disorders are from the DSM-IV-TR.16 CBT denotes cognitive behavioral therapy, and NA not applicable.

Differences in the number of adverse events in the sertraline group, as compared with the placebo group and the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group, were evaluated with the use of Fisher’s exact test, unless otherwise noted.

The reported P value was calculated with the use of Pearson’s chi-square statistic.

P<0.05 for the comparison between the sertraline group and the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group.

All harm-related adverse events and serious adverse events are reported (i.e., not limited only to those occurring in at least 3% of the subjects).

This event was considered to be possibly related to treatment.

Adverse Events

Subjects in the combination-therapy group had a greater number of study visits and therefore significantly more opportunities for elicitation of adverse events than did those in the other study groups, with a mean of 12.8±4.0 opportunities (range, 1 to 22) in the combination-therapy group, as compared with 9.9±3.6 (range, 1 to 14) in the sertraline group, 10.6±2.0 (range, 1 to 14) in the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group, and 9.7±4.2 (range, 1 to 14) in the placebo group (P<0.001 for all comparisons). Rates of adverse events, including suicidal and homicidal ideation, were not significantly greater in the sertraline group than in the placebo group. No child in the study attempted suicide. Among children in the cognitive-behavioral-therapy group, there were fewer reports of insomnia, fatigue, sedation, and restlessness or fidgeting than in the sertraline group (P<0.05 for all comparisons). For a list of mild adverse events that were not associated with functional impairment, as well as moderate and severe events, see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at www.nejm.org.

Discussion

Our study examined therapies that many clinicians consider to be the most promising treatments for childhood anxiety disorders. Our findings indicate that as compared with placebo, the three active therapies—combination therapy with both cognitive behavioral therapy and sertraline, cognitive behavioral therapy alone, and sertraline alone—are effective short-term treatments for children with separation and generalized anxiety disorders and social phobia, with combination treatment having superior response rates. No physical, psychiatric, or harm-related adverse events were reported more frequently in the sertraline group than in the placebo group, a finding similar to that for SSRIs, as identified in previous studies of anxious children.12,13,25 Few withdrawals from either treatment or the study were attributed to adverse events. Suicidal ideation and homicidal ideation were uncommon. No child attempted suicide during the study period.

Since they were recruited at multiple centers and locations, the study subjects were racially and ethnically diverse. However, despite intense outreach, the sample did not include the most socioeconomically disadvantaged children. Subjects were predominantly younger children and included those with ADHD and other anxiety disorders, factors that allow for generalization of the results to these populations. Conversely, the exclusion of children and teens with major depression and pervasive developmental disorders may have limited the generalizability of the results to these populations.

The observed advantage of combination therapy over either cognitive behavioral therapy or sertraline alone during short-term treatment (an improvement of 21 to 25%) suggests that among these effective therapies, combination therapy provides the best chance for a positive outcome. The superiority of combination therapy might be due to additive or synergistic effects of the two therapies. However, additional contact time in the combination-therapy group, which was unblinded, and expectancy effects on the part of both subjects and clinicians cannot be ruled out as alternative explanations. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the treatment effect in the combination-therapy group (with two subjects as the number needed to treat to prevent one additional event) suggests that children with anxiety disorders who receive quality combination therapy can consistently expect a substantial reduction in the severity of anxiety. An increased number of visits in the combination-therapy group resulted in increased opportunities for elicitation of adverse events. Consequently, the potential for expectancies among subjects, parents, and clinicians regarding the side effects of medications in the context of more visits may have increased the rate of some adverse events in the combination-therapy group and may limit conclusions that can be drawn regarding the rates of adverse events in combination therapy.

The positive benefit of cognitive behavioral therapy, as compared with placebo, adds new information to the existing literature.26 The number needed to treat for cognitive behavioral therapy in this study (three subjects) is the same as that identified in a meta-analysis of studies comparing subjects who were assigned to cognitive behavioral therapy with those assigned to a waiting list for therapy or to sessions without active therapy.14 Our study’s test of cognitive behavioral therapy included children with moderate-to-severe anxiety and addresses criticism of previous trials that included children with only mild-to-moderate anxiety.14 Before our study, cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety was considered to be “probably efficacious.”26 This evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy and other recent studies27,28 suggests that such therapy for childhood anxiety is a well-established, evidenced-based treatment.29 Given that the risk of some adverse events was lower in the behavioral-therapy group than in the sertraline group, some parents and their children may consider choosing cognitive behavioral therapy as their initial treatment.

The results of our study confirm the short-term efficacy of sertraline for children with generalized anxiety disorder25 and show that sertraline is effective for children with separation anxiety disorder and social phobia. The number needed to treat for sertraline in our study (three subjects) was the same as that previously identified in a meta-analysis15 of six randomized, placebocontrolled trials of SSRIs for childhood anxiety disorders.12,13,25,30,31 These studies and others27 suggest that SSRIs, as a class, are the medication of choice for these conditions. The titration schedule that we used, which emphasized upward dose adjustment in the absence of response and adverse events, suggests that the average end-point dose of sertraline in this study is the highest dose consistent with good outcome and tolerability. No adverse events were observed more frequently in the sertraline group than in the placebo group. In contrast to the apparent risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in studies of depression in children and adolescents,15 our study did not demonstrate any increased risk for suicidal behavior in the sertraline group. Given the benefit of sertraline alone or in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy and the limited risk of adverse events associated with the drug in our study, the well-monitored use of sertraline and other SSRIs in the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders is indicated.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and sertraline either in combination or as monotherapies appear to be effective treatments for these commonly occurring childhood anxiety disorders. Results confirm those of previous studies of SSRIs and cognitive behavioral therapy and, most important, show that combination therapy offers children the best chance for a positive outcome. Our findings indicate that all three of the treatment options may be recommended, taking into consideration the family’s treatment preferences, treatment availability, cost, and time burden. To inform more prescriptive selection of patients for treatment, further analysis of predictors and moderators of treatment response may identify who is most likely to respond to which32 of these effective alternatives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants (U01 MH064089, to Dr. Walkup; U01 MH64092, to Dr. Albano; U01 MH64003, to Dr. Birmaher; U01 MH63747, to Dr. Kendall; U01 MH64107, to Dr. March; U01 MH64088, to Dr. Piacentini; and U01 MH064003, to Dr. Compton) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Sertraline and matching placebo were supplied free of charge by Pfizer.

Dr. Walkup reports receiving consulting fees from Eli Lilly and Jazz Pharmaceuticals and fees for legal consultation to defense counsel and submission of written reports in litigation involving GlaxoSmithKline, receiving lecture fees from CMP Media, Medical Education Reviews, McMahon Group, and Di-Medix, and receiving support in the form of free medication and matching placebo from Eli Lilly and free medication from Abbott for clinical trials funded by the NIMH; Dr. Albano, receiving royalties from Oxford University Press for the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Versions, but not for interviews used in this study, and royalties from the Guilford Press; Dr. Piacentini, receiving royalties from Oxford University Press for treatment manuals on childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders and from the Guilford Press and APA Books for other books on child mental health and receiving lecture fees from Janssen-Cilag; Dr. Birmaher, receiving consulting fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, and Abcomm, lecture fees from Solvay, and royalties from Random House for a book on children with bipolar disorder; Dr. Rynn, receiving grant support from Neuropharm, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, consulting fees from Wyeth, and royalties from APPI for a book chapter on pediatric anxiety disorders; Dr. McCracken, receiving consulting fees from Sanofi-Aventis and Wyeth, lecture fees from Shire and UCB, and grant support from Aspect, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eli Lilly; Dr. Waslick, receiving grant support from Baystate Health, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, and GlaxoSmithKline; Dr. Iyengar, receiving consulting fees from Westinghouse for statistical consultation; Dr. March, receiving study medications from Eli Lilly for an NIMH-funded clinical trial and receiving royalties from Pearson for being the author of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, receiving consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Wyeth, and Glaxo-SmithKline, having an equity interest in MedAvante, and serving on an advisory board for AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson; and Dr. Kendall, receiving royalties from Workbook Publishing for anxiety-treatment materials. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

We thank the children and their families who made this study possible; and J. Chisar, J. Fried, R. Klein, E. Menvielle, S. Olin, J. Severe, D. Almirall, and members of NIMH’s data and safety monitoring board.

APPENDIX

The following investigators participated in this study: Steering Committee: J. Walkup (chair), A. Albano (cochair), S. Compton (executive secretary); Statistics-Experimental Design: S. Compton, S. Iyengar, J. March; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: P. Kendall, G. Ginsburg; Pharmacotherapy: M. Rynn, J. McCracken; Assessment: J. Piacentini, A. Albano; Study Coordinators: C. Keeton, H. Koo, S. Aschenbrand, L. Bardsley, R. Beidas, J. Catena, K. Dever, K. Drake, R. Dublin, E. Fontaine, J. Furr, A. Gonzalez, K. Hedtke, L. Hunt, M. Keller, J. Kingery, A. Krain, K. Miller, J. Podell, P. Rentas, M. Rozenmann, C. Suveg, C. Weiner, M. Wilson, T. Zoulas; Data Center: K. Sullivan, M. Fletcher; Cognitive Behavior Therapists: E. Gosch, C. Alfano, A. Angelosante, S. Aschenbrand, A. Barmish, L. Bergman, S. Best, J. Comer, S. Compton, W. Copeland, M. Cwik, M. Desari, K. Drake, E. Fontaine, J. Furr, P. Gammon, C. Gaze, R. Grover, H. Harmon, A. Hughes, K. Hutchinson, J. Jones, C. Keeton, H. Kepley, J. Kingery, A. Krain, A. Langley, J. Lee, J. Levitt, J. Manetti-Cusa, E. Martin, C. Mauro, K. McKnight, T. Peris, K. Poling, L. Preuss, A. Puliafico, J. Robin, T. Roblek, J. Samson, M. Schlossberg, M. Sweeney, C. Suveg, O. Velting, T. Verduin; Pharmacotherapists: M. Rynn, J. McCracken, A. Adegbola, P. Ambrosini, D. Axelson, S. Barnett, A. Baskina, B. Birmaher, C. Cagande, A. Chrisman, B. Chung, H. Courvoisie, B. Dave, A. Desai, K. Dever, M. Gazzola, E. Harris, G. Hirsh, V. Howells, L. Hsu, I. Hypolite, F. Kampmeier, S. Khalid-Khan, B. Kim, D. Kondo, L. Kotler, M. Krushelnycky, J. Larson, J. Lee, P. Lee, C. Lopez, L. Maayan, J. McCracken, R. Means, L. Miller, A. Parr, C. Pataki, C. Peterson, P. Pilania, R. Pizarro, H. Ravi, S. Reinblatt, M. Riddle, M. Rodowski, D. Sakolsky, A. Scharko, R. Suddath, C. Suarez, J. Walkup, B. Waslick; Independent Evaluators: A. Albano, G. Ginsburg, B. Asche, A. Barmish, M. Beaudry, S. Chang, M. Choudhury, B. Chu, S. Crawley, J. Curry, G. Danner, N. Deily, R. Dingfelder, D. Fitzgerald, P. Gammon, S. Hofflich, E. Kastelic, J. Keener, T. Lipani, K. Lukin, M. Masarik, T. Peris, T. Piacentini, S. Pimentel, A. Puliafico, T. Roblek, M. Schlossberg, E. Sood, S. Tiwari, J. Trachtenberg, P. van de Velde; Pharmacy: K. Truelove, H. Kim; Research Assistants: S. Allard, S. Avny, D. Beckmann, C. Brice, B. Buzzella, E. Capelli, A. Chiu, M. Coles, J. Freeman, M. Gringle, S. Hefton, D. Hood, M. Jacoby, J. King, A. Kolos, B. Lourea-Wadell, L. Lu, J. Lusky, R. Maid, C. Merolli, Y. Ojo, A. Pearlman, J. Regan, S. Rock, M. Rooney, N. Simone, S. Tiwari, S. Yeager.

References

- 1.Benjamin RS, Costello EJ, Warren M. Anxiety disorders in a pediatric sample. J Anxiety Disord. 1990;4:293–316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birmaher B, Yelovich AK, Renaud J. Pharmacologic treatment for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:1187–204. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Achenbach TM, Howell CT, McConaughy SH, et al. Six-year predictors of problems in a national sample of children and youth: I. Cross-informant syndromes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:336–47. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC. Psychopathology from adolescence into young adulthood: an 8-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1586–94. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pine DS. Child-adult anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:280–1. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199402000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurley D, Cohen P, Pine DS, Brook J. Discriminating depression and anxiety in youth: a role for diagnostic criteria. J Affect Disord. 1996;39:191–200. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:865–77. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein R. Anxiety disorders. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, Hersov L, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry: modern approaches. 3rd ed. Blackwell Scientific; London: 1995. pp. 351–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:100–11. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow M, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: a second randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:366–80. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Monk K, et al. Fluoxetine for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:415–23. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000037049.04952.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group Fluvoxamine for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1279–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104263441703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James A, Soler A, Weatherall R. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Coch rane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004690.pub2. CD004690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. text rev.: DSM-IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendall PC, Hedtke KA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: therapist manual. 3rd ed. Workbook Publishing; Ardmore, PA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idem . Coping Cat workbook. 2nd ed. Workbook Publishing; Ardmore, PA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendall PC, Gosch E, Furr JM, Sood E. Flexibility within fidelity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:987–93. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albano AM, Silverman WK. The anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV, child version: clinician manual. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guy W, Bonato R, editors. CGI: Clinical Global Impressions. National Institute of Mental Health; Chevy Chase, MD: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS): development and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1061–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller RG. Simultaneous statistical inference. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rynn MA, Siqueland L, Rickels K. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of children with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2008–14. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman WK, Pina AA, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:105–30. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Sallee FR, Ammerman RT, Crosby LA, Pathak S. SET-C versus fluoxetine in the treatment of childhood social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1622–32. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318154bb57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: a randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:282–97. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner KD, Berard R, Stein MB, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1153–62. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.March JS, Entusah AR, Rynn M, Albano AM, Tourian KA. A randomized controlled trial of venlafaxine ER versus placebo in pediatric social anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiesler DJ. Some myths of psychotherapy research and the search for a paradigm. Psychol Bull. 1966;65:110–36. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.