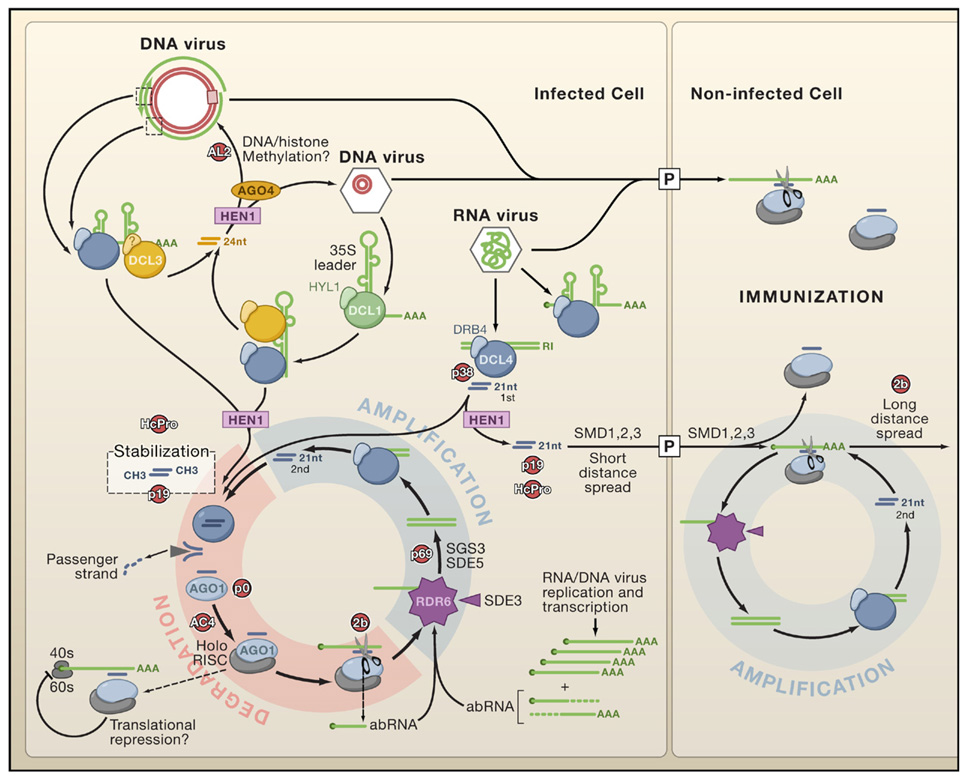

Figure 1. Antiviral Silencing in Arabidopsis.

Dicer-like proteins (DCLs) are represented in association with known and unknown cognate double-stranded (ds)RNA-binding proteins (DRBs). Note the indirect implication of DCL1 in viRNA biogenesis from DNA viruses (e.g., Cauliflower mosaic virus) and the putative contribution of DCL3-dependent viRNAs to viral DNA/histone methylation. DCL4 is the primary Dicer to detect RNA viruses and is replaced by DCL2 if suppressed (for example by the VSR P38; see also Figure 3B). AGO1 is presented as a major antiviral slicer, but other AGO paralogs are likely to be involved, potentially also mediating translational repression. All viRNAs are stabilized through HEN1-dependent 2′-O-methylation. The figure shows how primary viRNAs (1st) are amplified into secondary viRNAs (2nd) in the RDR6-dependent pathway. A similar scheme is anticipated with the salicylic acid-induced RDR1 (not shown; Diaz-Pendon et al., 2007). Aberrant (ab) viral mRNAs lacking a cap or polyA tail (AAA) can enter RNA-dependent RNA polymerase pathways independently of 1st viRNA synthesis. A DCL4-dependent silencing signal (arbitrarily depicted as free 21 nucleotide viRNAs) moves through the plasmodesmata (P) to immunize neighboring cells. Movement may be enhanced through further rounds of amplification involving viral transcripts that enter immunized cells. VSRs and potential endogenous silencing suppressors (red) represent genetic rather than direct physical interactions with host silencing components.