Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Although a variety of national organizations such as the Canadian Pain Society, the American Pain Society and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations have advanced the idea that pain should be assessed on a routine basis, there is little evidence that systematic pain assessment information is used routinely by clinicians even when it is readily available.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine whether systematic pain assessment information alters medical practitioners’ clinical practices.

METHODS:

A population of seniors with complex medical problems who were evaluated by case coordinators was studied. Case coordinators were assigned to either an experimental or control patient assessment condition. Control condition patients were assessed as usual. In the experimental condition, a psychometrically valid pain assessment battery as well as the Geriatric Depression Scale – Short Form (because depression and chronic pain are frequently comorbid) were integrated into the routine case coordination assessment. A summary of the results of the depression and pain assessments was subsequently sent to physicians via mail and fax. Patients were also given copies of the assessment summaries and were asked to discuss these with their physicians. Physicians’ medication prescriptions were monitored over time through the database of the provincial ministry of health.

RESULTS:

At the end of the study, no significant differences between experimental and control patients were found with respect to medications prescribed or patient self-reports of pain. Nonetheless, there was a significant relationship between Geriatric Depression Scale – Short Form scores and pain medications prescribed for patients in the experimental condition. Moreover, indexes of overall pain intensity did not change significantly over time.

CONCLUSIONS:

The findings do not support the idea that the availability of systematic pain assessment information leads to change in clinician’s medication practices. As such, educational interventions and public policy initiatives are needed to ensure that treatment providers do not only gather but also use pain assessment information.

Keywords: Assessment, Elderly, Older adults, Pain

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Bien que diverses organisations nationales, comme la Société canadienne de la douleur, l’American Pain Society et la Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations, aient proposé d’évaluer la douleur systématiquement, on dispose de peu de preuves selon lesquelles les données d’évaluation systématique de la douleur sont utilisées de routine par les médecins, même s’ils y ont accès.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer si les données d’évaluation systématique de la douleur influent sur les pratiques cliniques des médecins.

MÉTHODE :

Les auteurs ont étudié une population de personnes âgées aux prises avec des problèmes de santé complexes qui ont été évaluées par des coordonnateurs de cas. Les coordonnateurs de cas ont été assignés soit au groupe expérimental, soit au groupe témoin. Les patients du groupe témoin étaient évalués de la façon habituelle. Dans le groupe expérimental, on intégrait à l’évaluation de coordination habituelle des cas une série de tests psychométriques validés pour la mesure de la douleur, de même que l’échelle de dépression gériatrique (version abrégée), car on observe souvent concomitamment les composantes dépression et douleur chronique. On a ensuite posté et télécopié aux médecins un sommaire des résultats pour les composantes dépression et douleur. On a également remis aux patients une copie du sommaire et on les a invités à en discuter avec leur médecin. On a ensuite vérifié les ordonnances de médicaments rédigées par les médecins auprès de la base de données du ministère provincial de la Santé.

RÉSULTATS :

À la fin de l’étude, on n’a noté aucune différence significative entre les patients du groupe expérimental et ceux du groupe témoin pour ce qui est des médicaments prescrits ou des douleurs autosignalées par les patients. Néanmoins, on a noté un lien significatif entre les scores à l’échelle de dépression gériatrique (version abrégée) et les médicaments analgésiques prescrits aux patients du groupe expérimental. De plus, les indices d’intensité globale de la douleur n’ont pas changé significativement avec le temps.

CONCLUSION :

Les résultats n’appuient pas le concept selon lequel l’accès à des données d’évaluation systématique de la douleur modifie les pratiques des médecins en matière de prescription. À ce titre, il faut mettre en place des projets de sensibilisation et de politiques publiques pour veiller à ce que les professionnels de la santé ne se contentent pas de recueillir des données sur l’évaluation de la douleur, mais qu’ils les utilisent.

A variety of organizations, including the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations, the Canadian Pain Society, the American Pain Society and the Veterans Health Administration have advanced and stressed the importance of pain assessment (1). However, pain is underassessed and pain problems remain undertreated in a variety of populations including seniors and children (2–5). In fact, the undertreatment of pain in older adults and children is among the most pressing ethical concerns for pain clinicians (3).

Expert consensus groups have also stressed the importance of pain assessment (6–8). Nonetheless, attempts to evaluate the extent to which systematic pain assessment information – other than information gathered during routine medical and other related examinations – is used to make clinical decisions have been very scarce. Such evaluations are important for several reasons. Most importantly, from a health policy perspective, there are cost implications of increased use of routine systematic pain assessment. Given such cost implications and other resource considerations, it is important to demonstrate to decision makers that routine pain assessment affects clinical practices. If it does not affect such practices, more work would be needed to ensure that pain assessment information is integrated into the decision-making of front-line clinicians.

Although not much work has been conducted on the impact of assessment information on clinicians’ practices, one study that focuses on mental health practitioners (9) has demonstrated that, even when provided with data on standardized measures of psychological functioning, most mental health clinicians do not use these data in their treatment planning or monitoring. Within the pain arena, past research in an outpatient internal medicine clinic failed to find any evidence that routinely measuring pain as a ‘fifth vital sign’ improved pain management (10). Moreover, for more than one-fifth of the internal medicine clinic patients who reported pain, there was no mention of pain in their medical record.

In contrast, one study involving long-term care populations (11) produced promising results. More specifically, Fuchs-Lacelle et al (11) asked nursing staff to systematically and regularly assess pain (ie, approximately three times per week for three months) among nursing home patients with moderate to severe dementia, using a systematic observational procedure (12). A control group of nurses working with a separate group of patients completed an attention control observational measure that was not pain-specific. The results showed that use of PRN (pro re nata – taken as needed) pain medications increased for assessment group patients compared with the control group. Stress levels for nurses who conducted pain assessments also decreased compared with the control group, possibly because the assessment may have reduced uncertainty and decreased behavioural disturbance among long-term care residents (ie, chronic pain is known to lead to increased behavioural disturbances among seniors with dementia [7]). Interestingly, use of regularly scheduled medications did not change as a result of the intervention, possibly because the pain assessment information was either not communicated to the patients’ physicians and/or because physicians did not deem it to be relevant. Despite the aforementioned promising results on the integration of routine pain assessment in the long-term care setting (11), there is very limited research on the effects of integration of routine pain assessment into the care of seniors residing in the community.

For the purposes of the present investigation, we studied seniors with complex medical problems who were being assessed by case coordinators. Case coordinators routinely assess seniors with complex medical problems and then communicate with care providers about patient needs. The case coordination assessments typically include, but are not limited to, reviews of social history, physical environment, physical health history (eg, sleep, bladder and bowel functioning), nutrition and eating, and medication use. At the end of the assessment, case coordinators determine the level of need and arrange for various treatment services and referrals. Although case coordinators may consider pain, the assessment does not routinely include systematic pain assessment information.

The population of seniors was deemed ideal for the present study because pain is very prevalent among older adults. Specifically, it is estimated that pain affects more than 50% of older persons living in the community and over 80% of those residing in long-term care facilities (13). Moreover, chronic pain problems are highly comorbid with depression (14), which makes the assessment of depression important in this context.

Despite its high prevalence, pain tends to be underassessed and undertreated in seniors (4). We hypothesized that patients whose physicians were sent systematically collected and psycho-metrically sound pain assessment information would be prescribed more pain medications (ie, as reflected in either an increase in the dose or number of medications) than patients whose physicians were not sent such information. This would therefore help address the undertreatment of pain in this population. Moreover, we hypothesized that, at a follow-up assessment, experimental condition patients would manifest lower pain scores than patients in a control group. We also hypothesized that there would be a significant association between pain assessment scores and medications administered for experimental patients, but not control patients. Finally, we expected that experimental group participants, unlike control condition participants, would show a reduction in pain and associated distress scores over time.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were community-dwelling seniors 65 years of age or older with medically complex problems who were being assessed by case coordinators working for the local health region of a mid-sized metropolitan area. Potential participants were asked by their case coordinators if they would be interested in taking part in the study. Eligibility criteria included an age of 64 years or older, participation in an assessment regarding health care services with a case coordinator, and the ability to verbally respond to the case coordinator’s questions regarding health and health care services. Overall, 114 participants completed the study (58 in the experimental condition). An additional 59 participants were enrolled in the study but were not available for a follow-up assessment. Nonetheless, their medication data were included in all analyses that did not involve follow-up assessment scores. Reasons for not being available to complete the follow-up assessment included being too ill, being hospitalized, loss of interest in the study, moving to a long-term care facility and death. A comparison of the participants who completed the study and those who did not showed that the two groups did not differ with respect to demographic variables (ie, age, sex and education).

Information regarding prescribed medication was not available for 71 participants; therefore, they were not included in the analyses, resulting in 173 participants being included in the medication analyses (88 in the experimental condition). The mean (± SD) age of the participants was 80.74±7.86 years and they had 10.79±2.96 years of education. There were no differences between the experimental group and the control group regarding age, sex or education level. A total of 70.4% of participants were women. Data regarding pain and depression scores for the sample are available in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Pain and depression measures at baseline and follow-up

| Measure |

Experimental group |

Control group* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=88) | Follow-up (n=58) | Follow-up (n=56) | ||

| GDS-SF | 5.17±3.31 | 4.58±3.11 | 4.00±3.05 | |

| Box 21 – day | 38.20±31.25 | 31.93±26.37 | 31.52±29.17 | |

| Box 21 – week | 48.51±30.37 | 39.74±26.19 | 39.73±30.81 | |

| GPM-D | 4.66±2.53 | 4.02±2.64 | 3.87±2.78 | |

| GPM-I | 12.67±7.20 | 11.28±6.98 | 12.09±7.45 | |

| GPM-A | 2.19±1.60 | 1.96±1.43 | 2.14±1.49 | |

| GPM-S | 2.50±0.82 | 2.21±1.06 | 2.18±1.01 | |

| GPM-O | 2.39±1.76 | 1.91±1.63 | 2.00±1.70 | |

Data presented as mean ± SD.

Baseline scores were not collected from individuals in the control group. Geriatric Pain Measure (GPM) subscales: A Pain with ambulation; D Disengagement due to pain; I Pain intensity; O Pain with other activity; S Pain with strenuous activity. Box 21 refers to the 21-point box scale. GDS-SF Geriatric Depression Scale – Short Form

Procedure

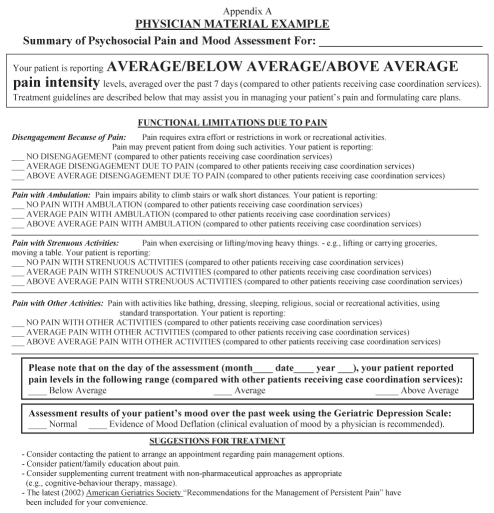

After receiving ethics clearance from both the University of Regina and the local health authority, as well as obtaining the necessary approval from the provincial ministry of health, 23 case coordinators were randomly assigned to a study condition (ie, experimental or control). Case coordinators assigned to the experimental group attended an instructional seminar conducted by the researchers on study procedures, including administration of the brief Pain Assessment Battery. When entering the present study, participants in the experimental group were administered a brief Pain Assessment Battery by their case coordinator in addition to the regular routine interview. The Pain Assessment Battery included a 21-point box scale (15), the Geriatric Pain Measure (GPM) (16), the Geriatric Depression Scale – Short Form (GDS-SF) (17) and a pain drawing (18). The case coordinator scored the 21-point box scale questionnaire immediately and classified the score on each measure as reflecting ‘below average pain’, ‘average pain’ and ‘above average pain’. These determinations were based on typical scores that were obtained in a pilot study (unpublished data) of a different sample of 46 senior case coordination patients. Scores that were greater than one SD above the mean were deemed to be ‘above average’ and scores that were less than than one SD below the mean were deemed to be ‘below average’. The scores for pain from the GPM and GDS-SF, as well as pain locations from a pain drawing completed by the patients, were then entered into appropriate areas of the summary sheet (Appendix A). The summary sheet was then sent to the patients’ physicians with patient consent along with a summary of the American Geriatrics Society guidelines for pain management among seniors (6), which include recommendations for both pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies. Participants in the experimental condition were also given a copy of the results and were advised to take the summary with them during their next medical appointment. In addition to receiving the information by fax from the patients’ case coordinators, a paper copy of the results was also mailed to physicians by study personnel. Before the present study began, it was announced in local physicians’ meetings. Moreover, most general practice physicians in the city were mailed general information about this program of research. Participants in the control group underwent the regular routine interview (ie, assessment as usual) without the Pain Assessment Battery. All participants were informed that they would be contacted by study personnel for a follow-up interview three months later.

Three months after the initial case coordination interview, all participants underwent an interview by an independent assessor (ie, a research staff member, not a case coordinator) and were administered the Pain Assessment Battery, along with a brief questionnaire concerning satisfaction with health care services. Although the face-valid and internally consistent patient satisfaction questionnaire is not the focus of the present investigation, it is noted that there were no group differences (control versus experimental group) with respect to satisfaction with health care services. All participants were given a copy of the results of the pain assessment.

Information regarding prescribed medications for three months before and six months following study enrollment was provided by the ministry of health (with patient consent) and was quantified using a modified version of the Medical Quantification Scale Version III (MQS-III) (19).

Measures

21-point box scale (15):

The 21-point box scale consists of 21 boxes with numbers appearing in increments of 5 and ranging from 0 to 100; respondents rate their pain using the numeric scale. Higher scores are indicative of higher levels of pain. This measure was selected because it has been shown to have psychometric properties superior to those of other brief tools used with older adults (20).

GPM (16):

The GPM was selected because it is a multidimensional assessment tool that has been developed specifically for use with older persons. Respondents answer 22 yes/no questions concerning their pain, as well as two questions concerning the intensity of their pain (ranging from 0 to 10). The following subscale scores are obtained: pain intensity, pain with strenuous activity, pain with ambulation, disengagement because of pain and pain with other activity. Higher scores are indicative of greater amounts of pain. Psychometric properties of the GPM are well established (16,21).

GDS-SF (17,22):

The GDS-SF was selected because, unlike depression assessment tools commonly used with younger persons, it avoids the use of somatic items that can confound symptoms of depression with other physical symptoms that are common among older persons. The GDS-SF consists of 15 yes/no questions. Higher scores are indicative of a depressed mood. The GDS-SF is a clinically useful screen for depression among older adults and has evidence to support its validity and reliability among community-dwelling older adults (22).

Pain drawing (18):

Respondents are shown a picture of the human body and told to mark where they experience pain. Although this measure was not scored, the pain drawing was sent with the pain summary sheet to provide physicians with additional descriptive information regarding patients’ pain.

Medication index:

The index used to quantify medications was based on the MQS-III (19). The MQS-III is a tool that is used to objectively quantify medications into a single clinically meaningful numeric value known as the MQS score. The MQS score is calculated by using a detriment weight assigned for each class of medication multiplied by the dose of the medication (1 = subtherapeutic, 2 = lower 50% of the therapeutic dose range, 3 = upper 50% of the therapeutic dose range and 4 = supratherapeutic). The detriment weight is related to the drug’s potential for abuse or addiction, or the severity of negative side effects. For the purposes of the present study, a modified formula was used because the recommended daily frequency of administration of the prescribed single dose was not available through the ministry of health databases. The modified formula was the product of the detriment weight for the medication, the amount prescribed for each dose and the number of doses (usually tablets or capsules) prescribed for each patient. Moreover, dose ranges were evaluated (eg, ‘subtherapeutic’ or ‘lower 50% of the therapeutic dose’) specifically for a geriatric population using the 2004 Lexi-Comp’s Geriatric Dosage Handbook (23). Initial psychometric data regarding the MQS-III, including validity and reliability, are good (19).

RESULTS

Initial analysis

To test the hypothesis that experimental group participants would present with lower follow-up pain and associated distress scores than control group participants, independent samples t tests were conducted on all pain outcome measures and the GDS-SF (17). Contrary to expectations, no group differences were found.

To test the hypothesis that experimental group patients would experience reductions in pain levels and associated distress over time, paired samples t tests were conducted to investigate differences between baseline and follow-up scores on the pain variables (15), the GPM (16) and the GDS-SF (17). Results revealed a significant difference on the disengagement subscale of the GPM (t56=2.12, P<0.05) indicating that, compared with baseline, participants in the experimental group reported lower pain-related activity avoidance at follow-up. There was also a significant change over time with respect to the strenuous activity subscale of the GPM (t56=2.27, P<0.05), which suggests that participants in the experimental group reported less pain related to strenuous activities compared with their baseline. Nonetheless, overall pain levels, as reflected in the 21-point box scale and the pain intensity subscale of the GPM, remained unchanged.

Linear and linear mixed effects modelling

There were no significant differences between the experimental and control groups with respect to the time that elapsed between the case coordination assessment and the first medication prescription. Of the participants for whom medication data were available, as described in the Participants section above, the average time that elapsed between the case coordination assessment and the first medication prescription was 12.86±12.64 days. Given the longitudinal nature of the data, linear mixed effects regression models with random intercepts at the patient level were fitted with respect to the baseline and follow-up medication index scores for all patients in the experimental and control groups. The goal of the analysis was to test the hypothesis that medication prescription trends would differ between the experimental and control group patients. The analysis enabled quantification of the medication index trends and testing for potential group differences (experimental versus control groups) with respect to medication index scores (ie, medications prescribed). Overall, the medication index scores fluctuated over repeated visits, indicating no systematic trends during the post pain assessment period (medication index including the number of prescribed doses: mean slope = −0.0364, standard error [se]=1.90, P=0.98; medication index without including the number of prescribed doses: mean slope = 0.00094, se=0.026, P=0.97). The analysis did not suggest significant differences between the experimental and control groups in the mean medication index values or medication index trends over repeated visits.

To test the hypothesis concerning the association between pain, as well as associated distress scores, with medications prescribed, the potential relations between the baseline medication index scores and the corresponding pain scores were examined via linear regression analysis, using the data for patients in the experimental group only. The analysis of the GPM subscale scores yielded only one significant relationship. This was reflected in a relatively strong association between (higher) GDS-SF scores and (higher) medication index scores without including the number of prescribed doses (mean effect = 111.899, se=50.73, P=0.03). No association was found between the GDS-SF scores and the medication index with the number of prescribed doses taken into account. No significant association was found between the medication index and other pain scores (21-point box scale and the other GPM subscales).

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the findings of Mularski et al (10), based on research with internal medicine outpatients, our results did not support the notion that providing pain assessment information to front-line medical service providers leads to significant change in clinical practices (as reflected in medical prescriptions). This can be interpreted in different ways. One possible interpretation is that the assessment information is simply ignored. Another possibility is that pain is assessed very well by front-line medical providers and the new psychometric assessment information adds very little. If this were the case, one may expect a reasonable correspondence between medications prescribed (as reflected in experimental group medication index scores) and pain assessment scores in the experimental group because the control group was not assessed at baseline. The results suggested that pain assessment scores were unrelated to the medications administered. This suggests that it would have been beneficial to consider the results of the systematic pain assessment when making medication regimen recommendations, especially considering that experimental and control group pain scores did not differ at follow-up.

It is also important to stress that our brief Pain Assessment Battery approach is more thorough than the less comprehensive approaches to assessment that were used to test the utility of assessing pain as a fifth vital sign (10). In fact, research with older adults has supported the need for a multidimensional pain assessment and provided evidence that less comprehensive, nonmultidimensional approaches are often insufficient (24). Therefore, our finding that the results of a multidimensional pain assessment approach do not appear to have been used by clinicians raises greater concerns than those of previous investigations demonstrating that the results of simpler (ie, less comprehensive) approaches to pain assessment were not used (10).

Despite the absence of improvement in overall pain scores over time, we did find an improvement with respect to pain with strenuous activity and disengagement because of pain among experimental group participants. It is difficult to interpret the significance of this finding in the absence of comparative change data from the control group, who did not undergo a pain assessment at baseline. It is possible that physicians recommended treatments other than medication for the pain problems, but it is unlikely that the observed improvements were due to the assessment information, given that control and experimental participants did not differ at follow-up with respect to any of the pain indexes.

The findings concerning the absence of change in overall pain indexes over time and the absence of a correspondence between pain levels and medications prescribed are troubling. Specifically, these findings raise concerns because the participant pain scale scores were quite high compared with scores obtained by other seniors receiving care (20). Moreover, the finding that overall pain scores (ie, 21-point box scale and GPM pain intensity subscale) were not significantly reduced from pre- to post-test in the experimental group of patients contributes to the pre-existing literature because it provides further evidence of the undertreatment of pain among older adults within the context of a prospective longitudinal design. The identified association between depression and prescribed medications suggests that physicians may be more likely to attend to pain concerns when they are accompanied by depression. This may be due to knowledge of the high comorbidity between persistent pain and depression (14). Nonetheless, this possibility is open for further study.

As Garland et al (9) have pointed out, a clinician’s personal beliefs are usually more influential than scientific evidence (25), such as the evidence derived from psychometrically valid questionnaires. This is rather unfortunate because anecdotal observations and intuitions are subject to many perceptual biases and are less reliable than results derived from standardized assessment tools (25,26). Nonetheless, some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. In the case of our research participants, there may have been other reasons (ie, other than the possibility that pain assessment information was ignored) for the outcome of no changes in prescriptions as a function of pain assessment results. For example, it is possible that the assessment information resulted in physicians recommending more nonpharmacological interventions that we were not able to track, given the limitations of the available database. Moreover, it is possible that many patients did not take their assessment summary sheets to their physicians for discussion – although copies of these sheets were both mailed and faxed to the physicians – which could have contributed to the underemphasis of the pain assessment results. It is also possible that some patients indicated they did not desire an increase in their pain medication. Finally, we note that the patients in the experimental condition underwent two pain assessments; the first was the experimental manipulation, and the second was the determination of whether the initial experimental group assessment led to any differences at follow-up. Although the repetition that only pertained to the experimental group may have affected the results in some way, we point out that all of our assessment tools were of established reliability and believe that the impact of repeated testing on the results was minimal.

Recommendations for the routine assessment of pain as a fifth vital sign are based on the assumption that measurement, identification and documentation of pain should lead to improved management (10,27). However, to our knowledge there is no support for this assumption outside of long-term care facilities in which ongoing pain assessment has been shown to lead to changes in clinical practice (11). In addition, if organizations such as the Canadian Pain Society and the American Pain Society are going to be effective in promoting the importance of systematic pain assessment with decision makers, it is essential to accumulate evidence to support the effectiveness of pain assessment, given likely concerns about the fiscal and resource implications associated with wider use of systematic pain assessment. As such, additional educational interventions and public policy initiatives are needed to ensure that treatment providers not only obtain, but also use pain assessment information. It is the successful implementation and evaluation of such educational interventions that would be most likely to increase the use of systematic pain assessment.

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The support of the Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region is gratefully acknowledged. Thomas Hadjistavropoulos is supported by the RBC Foundation.

APPENDIX

REFERENCES

- 1.Turk DC.Progress and directions for the agenda for pain management<http://www.ampainsoc.org/pub/bulletin/sep04/pres2.htm> (Version current at May 20, 2009).

- 2.Bauchner H. Procedures, pain, and parents. Pediatrics. 1991;87:563–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrell BR, Novy D, Sullivan MD, et al. Ethical dilemmas in pain management. J Pain. 2001;2:171–80. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin R, Williams J, Hadjistavropoulos T, Hadjistavropoulos HD, MacLean M. A qualitative investigation of seniors’ and caregivers’ views on pain assessment and management. Can J Nurs Res. 2005;37:142–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutters KA, Miaskowski C. Inadequate pain management and associated morbidity in children at home after tonsillectomy. J Pediatr Nurs. 1997;12:178–85. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(97)80075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The management of chronic pain in older persons AGS Panel on Chronic Pain in Older Persons. American Geriatrics Society. Geriatrics. 1998;53(Suppl 3):S8–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Geriatrics Society releases persistent pain management guideline. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2002;16:127–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadjistavropoulos T, Herr K, Turk DC, et al. An interdisciplinary expert consensus statement on assessment of pain in older persons. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(1 Suppl):S1–43. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31802be869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garland AF, Kruse M, Aarons GA. Clinicians and outcome measurement: What’s the use? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2003;30:393–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02287427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mularski RA, White-Chu F, Overbay D, et al. Measuring pain as the 5th vital sign does not improve quality of pain management. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:607–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs-Lacelle S, Hadjistavropoulos T, Lix L. Pain assessment as intervention: A study of older adults with severe dementia. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:697–707. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318172625a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs-Lacelle S, Hadjistavropoulos T. Development and preliminary validation of the pain assessment checklist for seniors with limited ability to communicate (PACSLAC) Pain Manag Nurs. 2004;5:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlton JE. Core curriculum for professional education in pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: A literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2433–45. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen MP, Miller L, Fisher LD. Assessment of pain during medical procedures: A comparison of three scales. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:343–9. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199812000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrell BA, Stein WM, Beck JC. The Geriatric Pain Measure: validity, reliability and factor analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1669–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margolis RB, Tait RC, Krause SJ. A rating system for use with patient pain drawings. Pain. 1986;24:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harden RN, Weinland SR, Remble TA, et al. Medication Quantification Scale Version III: Update in medication classes and revised detriment weights by survey of American Pain Society physicians. J Pain. 2005;6:364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chibnall JT, Tait RC. Pain assessment in cognitively impaired and unimpaired older adults: A comparison of four scales. Pain. 2001;92:173–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clough-Gorr KM, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. The self-administered 24-item geriatric pain measure (GPM-24-SA): Psychometric properties in three European populations of community-dwelling older adults. Pain Med. 2008;9:695–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman B, Heisel MJ, Delavan RL. Psychometric properties of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in functionally impaired, cognitively intact, community-dwelling elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1570–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semla TP, Beizer JL, Higbee MD. Lexi-Comp’s Geriatric Dosage Handbook. Charlotte: Baker & Taylor Company; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadogan MP, Edelen MO, Lorenz KA, et al. The relationship of reported pain severity to perceived effect on function of nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:969–73. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garb HN. Studying the Clinician: Judgement Research and Psychological Assessment. Washington: American Psychological Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meehl PE. Clinical versus Statistical Prediction: A Theoretical Analysis and Review of the Evidence. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadgood MC, Miller PJ, Mathews PA. Relieving the agony of the new pain management standards. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2000;17:333–41. doi: 10.1177/104990910001700511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]