Abstract

Background and purpose:

Activation of cannabinoid (CB) receptors decreases nociceptive transmission in inflammatory or neuropathic pain states. However, the effects of CB receptor agonists in post-operative pain remain to be investigated. Here, we characterized the anti-allodynic effects of WIN 55,212-2 (WIN) in a rat model of post-operative pain.

Experimental approach:

WIN 55,212-2 was characterized in radioligand binding and in vitro functional assays at rat and human CB1 and CB2 receptors. Analgesic activity and site(s) of action of WIN were assessed in the skin incision-induced post-operative pain model in rats; receptor specificity was investigated using selective CB1 and CB2 receptor antagonists.

Key results:

WIN 55,212-2 exhibited non-selective affinity and agonist efficacy at human and rat CB1 versus CB2 receptors. Systemic administration of WIN decreased injury-induced mechanical allodynia and these effects were reversed by pretreatment with a CB1 receptor antagonist, but not with a CB2 receptor antagonist, given by systemic, intrathecal and supraspinal routes. In addition, peripheral administration of both CB1 and CB2 antagonists blocked systemic WIN-induced analgesic activity.

Conclusions and implications:

Both CB1 and CB2 receptors were involved in the peripheral anti-allodynic effect of systemic WIN in a pre-clinical model of post-operative pain. In contrast, the centrally mediated anti-allodynic activity of systemic WIN is mostly due to the activation of CB1 but not CB2 receptors at both the spinal cord and brain levels. However, the increased potency of WIN following i.c.v. administration suggests that its main site of action is at CB1 receptors in the brain.

British Journal of Pharmacology (2009) 157, 645–655; doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00184.x; published online 3 April 2009

Keywords: cannabinoid; CB1; CB2; site of action; skin incision; WIN 55,212-2; mechanical allodynia

Introduction

Cannabinoid (CB) receptors have emerged as an attractive therapeutic target for pain management in recent years (Walker and Hohmann, 2005; Pacher et al., 2006). CB activity is mediated via the activation of inhibitory G-protein coupled CB receptors, namely CB1 and CB2 receptors (Pertwee, 2001; Walker and Hohmann, 2005). CB1 receptors are expressed at all levels of the pain-modulating pathways, including the primary afferent fibres, dorsal root ganglia (DRG), dorsal horn of the spinal cord and supraspinal sites, whereas CB2 receptors are primarily expressed in immunocompetent cells and are not thought to be present on neuronal cells of the central nervous system (CNS) (Piomelli, 2005; Walker and Hohmann, 2005; Agarwal et al., 2007). Correspondingly, endocannabinoid concentrations are increased along the nociception-relevant somatosensory neuraxis in various pain states (Walker and Hohmann, 2005; Mitrirattanakul et al., 2006), and anandamide has been shown to inhibit carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia, capsaicin-induced oedema and formalin-induced pain in rats (Calignano et al., 1998; Richardson et al., 1998a; Walker and Hohmann, 2005). Additionally, electrophysiological experiments have shown CB receptor activation following carrageenan injection and anandamide decreased carrageenan-evoked spinal neuronal response in rats (Sokal et al., 2003).

In animal studies, the anti-nociceptive efficacy of CBs and analogues has been demonstrated in several models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Walker and Hohmann, 2005). Synthetic CB agonists, such as WIN 55,212-2 (WIN), are potent activators of CB receptors and have demonstrable analgesic activity in rodents, reducing complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA)-induced inflammatory pain, formalin-induced persistent nociception (Tsou et al., 1996; Martin et al., 1999), and neuropathic pain caused by peripheral nerve injury (Fox et al., 2001; Costa et al., 2004), toxic nerve damage (Pascual et al., 2005) and diabetic neuropathy (Dogrul et al., 2004). Numerous studies have demonstrated that activation of CB receptors at several levels along the pain-modulating pathways can reduce nociceptive transmission, indicating that multiple sites of action are implicated in the anti-nociceptive effects of WIN. However, the relative contribution of each of these sites, or different subtypes of CB receptors, to the analgesic effects of systemic CB agonists remains unclear (Walker and Hohmann, 2005). Much less is known about the analgesic activity of CBs in post-operative pain (Valenzano et al., 2005).

Paw incision in rats induces a variety of nocifensive behaviours that parallel the time course of post-operative pain in humans (Brennan et al., 1996). This model has been widely used to determine the analgesic profile of novel and existing analgesic agents (Zahn and Brennan, 1998; Wang et al., 2000; Pogatzki et al., 2002; Brennan et al., 2005; LaBuda et al., 2005; Valenzano et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2005). The present study was undertaken to characterize the anti-nociceptive effects of WIN, and to explore the relative contributions of supraspinal, spinal and peripheral CB receptors to mechanical hypersensitivity in a rat paw incision model of post-operative pain. Additionally, the potential CB receptor subtypes that mediate the analgesic activity of WIN in this model were also investigated.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were performed in an AAALAC-accredited facility and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Abbott Laboratories. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (300–350 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were either housed five per cage or single-housed (animals implanted with i.t. catheters or i.c.v. cannulae). Animals were acclimated to the laboratory environment for 5–7 days before entering the study. All animals were kept in a temperature-regulated environment under a controlled 12 h light–dark cycle with lights on at 6:00 am. Food and water were provided ad libitum.

In vitro binding assays and measurement of cAMP in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells

The selectivity of WIN for CB1 or CB2 receptors was assessed by performing competition-binding experiments in membranes prepared from HEK or the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines, which stably express the human CB2 (hCB2) or CB1 (hCB1) receptors as previously described (Yao et al., 2006; 2008). For in vitro binding assays, membranes (CB1 or CHO-K1) were incubated at 30°C for 90 min with 1 nmol·L−1[3H]-CP 55,940 in 250 µL of assay buffer (50 mmol·L−1 Tris, 2.5 mmol·L−1 EDTA, 5 mmol·L−1 MgCl2 and 0.5 mg·mL−1 fatty acid free BSA, pH 7.4) in the presence of increasing concentration of unlabeled competitor compounds (Yao et al., 2008). Competitive binding at the hCB2 receptor was conducted under the same conditions except the [3H]-CP 55,940 concentration used was 0.5 nmol·L−1. Data were analysed using GraphPad PRISM™, v. 3.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Ki values from competition binding assays were determined with one-site competition curve fitting using the Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Rat cortical membranes were prepared from rat cerebral cortex purchased from Pel-Freez Biologicals (Roger, AR, USA). The assay conditions for binding to rat cortical membranes were similar to those for rat CB1 receptor binding using recombinant receptors, except that the protein concentration was 10-fold higher.

The cyclase functional assays were performed using the DiscoverX HitHunter cAMP assay kit according to the vendor's protocol as previously described (Yao et al., 2006; 2008). The CB receptor agonist CP 55,940 was used as the positive control for EC50 determination, in which 10 µmol·L−1 CP 55,940 was measured as 100% efficacy. EC50 values were calculated by curve fitting of sigmoidal dose response from Prism (GraphPad). All EC50 values are presented as mean ± SEM.

Surgical preparation

The surgical procedure of paw incision was performed under isoflurane (2–3%) anesthesia as previously described (Brennan et al., 1996). Briefly, the plantar aspect of the right hind paw was placed through a hole in a sterile plastic drape. A longitudinal incision (1 cm) was made through the skin and fascia, starting 0.5 cm from the proximal edge of the heel and extending towards the toes, the plantar muscle was elevated and incised longitudinally leaving the muscle origin and insertion points intact. After haemostasis with gentle pressure, the skin was apposed with two mattress sutures (5–0 nylon).

Intrathecal (i.t.) catheterization was performed following the procedure as described (Yaksh and Rudy, 1976) in some animals under isoflurane (2–3%) anesthesia. In these animals, a PE-5 catheter (Marsil Enterprises, San Diego, CA, USA) was inserted through the atlanto-occipital membrane via a small hole in the cisterna magna. The catheter was then advanced 8.5 cm caudally such that the tip ended in the intrathecal space around the lumbar enlargement. The catheter was then secured to the musculature at the incision site. The catheter implantation was performed at least 7 days prior to paw incision surgery.

For intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) cannulation, guide cannulae (22 gauge) were implanted into the left lateral ventricle of rats anesthetized with pentobarbital (50–60 mg·kg−1, i.p.) in a separate group of animals. The cannula was located 1.6 mm lateral to midline and 1.0 mm caudal to Bregma, with a depth of 4.5 mm (Paxinos and Watson, 1982). Cannula placement was performed at least 7 days prior to paw incision. Cannula placement technique was verified by infusion of 0.5% fast-green dye in saline solution and subsequent dissection in a pilot study, with >95% accuracy of cannula implantation.

Behavioural assessment

A quantitative allodynia assessment technique was conducted to measure mechanical allodynia using calibrated von Frey filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) as previously described (Chaplan et al., 1994) in all animals 120 min following surgery. Rats were placed into inverted individual plastic containers (20 × 12.5 × 20 cm) on top of a suspended wire mesh grid, and acclimated to the test chambers for 20 min. The von Frey filaments were presented perpendicularly to the plantar surface pointing towards the medial side of the incision (Brennan et al., 1996), and then held in this position for approximately 8 s with enough force to cause a slight bend in the filament. Positive responses included an abrupt withdrawal of the hind paw from the stimulus, or flinching behaviour immediately following removal of the stimulus. A 50% paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was determined using an up-down procedure (Dixon, 1980).

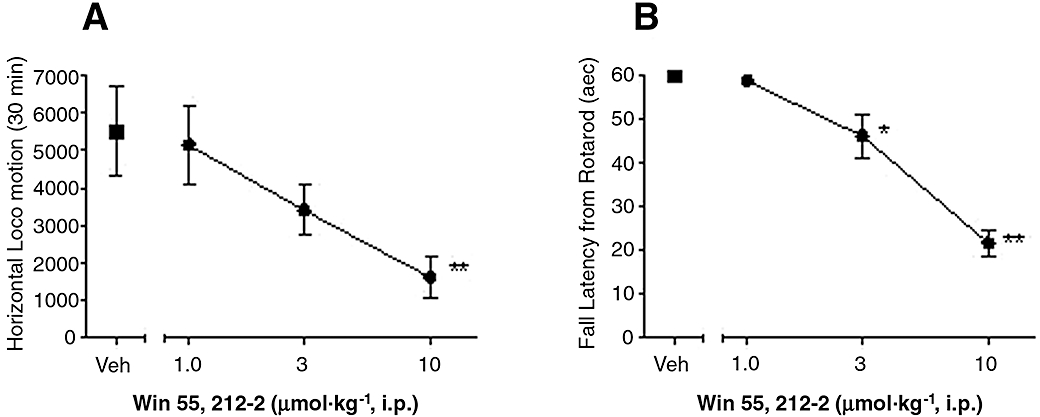

Horizontal exploratory behaviour was measured in an open field using photobeam activity monitors (AccuScan Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). Rats were placed into 42 × 42 × 30 cm activity chambers where photobeam breaks were recorded for 30 min. For rotarod performance, animal performance was measured using an accelerating rotarod apparatus (Omnitech Electronics, Inc. Columbus, OH). Rats were placed onto a 9 cm diameter rod, which increased in speed from 0 to 20 r.p.m. for a 60 s period. The time required for the rat to fall from the rod was automatically recorded, with a maximum cut-off of 60 s. Both Horizontal exploratory behaviour and rotarod performance were assessed 30 min following systemic WIN administration.

Experimental groups and compound administration

Systemic administration of WIN alone and pretreatment with a CB1 or a CB2 receptor antagonist

WIN (1, 3 and 10 µmol·kg−1, i.e. 0.43, 1.3 and 4.3 mg·kg−1) was administered i.p. 90 min following hind paw incision, and mechanical allodynia was determined 30 min post-treatment (2 h post-surgery). Because of the robust nociceptive behaviours observed in our previous time-course experiment (Zhu et al., 2005), the 2 h time point was chosen to study the pharmacological characterization in acute post-operative pain and to be able to compare our data with the previously published pharmacological data using this model. To determine the CB receptor subtypes responsible for WIN-induced analgesic efficacy, animals were treated i.p. with either a CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (SR1; 30 µmol·kg−1, i.e. 14 mg·kg−1), or a CB2 receptor antagonist SR144528 (SR2; 10 µmol·kg−1, i.e. 4.8 mg·kg−1) 15 min prior to WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.) treatment. Behavioural changes were evaluated 30 min following WIN administration. We have previously demonstrated that pretreatment with SR2 at 10 µmol·kg−1, but not SR1 at 30 µmol·kg−1, effectively blocked analgesic activity induced by A-796260 (a selective CB2 agonist) in the same rat model of post-operative pain, whereas SR1 or SR2 given alone had no analgesic activity (Yao et al., 2008).

To determine the potential confounding effects of WIN on behaviour, exploratory behaviour and motor coordination were examined by horizontal exploratory activity and rotarod performance in naïve rats 30 min following WIN (1, 3 and 10 µmol·kg−1, i.p.).

Peripheral, injection of WIN in the paw, pretreatment with i.pl. SR1 or SR2 before systemic WIN

Systemically inactive doses of WIN (30, 100, 300 nmol per paw) were injected into the plantar region of the injured paw (i.pl.), 90 min following hind paw injury. To explore the possible systemic diffusion, WIN (100, 300 nmol per paw) was also injected into the contralateral, normal paw in a separate group of animals. To evaluate the peripheral contribution of the CB receptor subtypes to WIN-induced analgesic efficacy, SR1 or SR2 (150 nmol per paw) was subsequently injected i.pl. into the injured paw, 15 min prior to the systemic administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p., 90 min following skin incision) in a separate experiment. Mechanical allodynia was assessed 30 min following i.pl. or i.p. injection of WIN.

Spinal application of WIN, pretreatment with i.t. SR1 or SR2 before systemic WIN

For intrathecal delivery, WIN (30, 100, 300 nmol per rat) was infused via an implanted catheter over 1 min, 90 min following surgery. The catheter was subsequently flushed with 5 µL of sterile water. To examine the spinal contribution of CB receptor subtypes to WIN-induced analgesic efficacy, SR1 or SR2 (150 nmol per rat) were delivered i.t. 15 min before the systemic administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p., 90 min following skin incision) in a separate group of animals. Mechanical allodynia was assessed 30 min following i.t. or i.p. injection of WIN.

Supraspinal infusion of WIN, pretreatment with i.c.v. SR1 or SR2 before systemic WIN

For i.c.v. administration, WIN (3,10, 30, 100 nmol per rat) was infused via a 28-gauge injection cannula extending 1 mm beyond the guide cannula tip over 1 min. To investigate the supraspinal contribution of CB receptor subtypes to WIN-induced analgesic efficacy, SR1 or SR2 (150 nmol per rat) was i.c.v. infused 15 min before the systemic administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p., 90 min following skin incision) in a separate group of animals. Mechanical allodynia was assessed 30 min following i.c.v. or i.p. injection of WIN.

Data analysis of behavioural experiments

In vivo data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated using analysis of variance (anova) followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison (GraphPad Prism). P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. All behavioural experiments were performed by experimenters unaware of the treatment received by the animals.

Materials

SR141716A (a CB1 receptor antagonist, SR1, molecular weight, 463.8), and SR144528 (a CB2 receptor antagonist, SR2, molecular weight, 476.1) were synthesized at Abbott Laboratories as previously described (Yao et al., 2006). [3H]CP 55,940 (a non-selective CB receptor agonist), WIN 55212-2 (a non-selective CB receptor agonist, WIN, molecular weight, 426.5], dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HBC) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). SR1, SR2 and WIN were dissolved in a solution of DMSO/HBC at a volume of 2.0 mL·kg−1 for intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration (10:90, V/V), 25 µL for intraplantar (i.pl.) paw injection (20:80, V/V) and 10 µL for intrathecal (i.t.) delivery followed by a 5 µL sterile water flush, or intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusion (40:60, V/V). All solutions were freshly prepared on the day of the experiments.

Results

Radioligand binding studies and measurement of cAMP

The affinity of WIN, SR1 and SR2 for human CB1 (hCB1) and CB2 (hCB2) receptors were measured using competition radioligand binding assays on CHO-K1 and HEK293 cell membranes expressing the recombinant receptors. WIN showed high affinity for hCB2 (Ki = 1.32 ± 0.07 nmol·L−1, n = 38) and a lower affinity for hCB1 receptors (Ki = 15.34 ± 0.12 nmol·L−1, n = 25). SR1 showed high hCB1 receptor binding selectivity (Ki = 2.05 ± 0.13 nmol·L−1 for hCB1, n = 24; Ki = 392.5 ± 0.12 nmol·L−1 for hCB2, n = 10), whereas SR2 showed higher hCB2 receptor binding affinity (Ki = 6.06 ± 0.09 nmol·L−1 for hCB2, n = 14; Ki = 263.85 ± 0.08 nmol·L−1 for hCB1, n = 12). Binding assays for rat CB1 and rat CB2 receptors were performed on HEK293 cell membranes expressing rat recombinant CB receptors. The affinity of WIN for rCB2 (1.4 ± 0.12 nmol·L−1, n = 18) was comparable to that of hCB2 receptors but the affinity for rCB1 (4.48 ± 0.08 nmol·L−1, n = 11) was considerably higher than that of hCB1 receptors. Similarly, SR1 showed high rCB1 receptor binding selectivity (Ki = 0.7 ± 0.1 nmol·L−1 for rCB1, n = 6; Ki = 126.55 ± 0.17 nmol·L−1 for rCB2, n = 4), whereas SR2 showed higher rCB2 receptor binding affinity (Ki = 1.65 ± 0.28 nmol·L−1 for rCB2, n = 6; Ki = 428.26 ± 0.17 nmol·L−1 for hCB1, n = 6). The affinity of WIN, SR1 and SR2 was also determined for native (rat) CB1 receptor using cell membranes prepared from rat cerebral cortex. WIN and SR1 showed high binding affinity for rat cortex CB1 receptors (Ki = 12.37 ± 0.057, n = 2; Ki = 2.77 ± 0.04 n = 4), whereas SR2 showed no binding affinity for rat cortex CB1 receptors (Ki > 1 µmol·L−1, n = 4). These data showed that the affinity of WIN, SR1 and SR2 in the native binding system is well correlated with its binding affinity in the recombinant system. Taken together, these binding data confirm that WIN is a non-selective ligand for both CB1 and CB2 receptors, SR1 is a selective ligand for CB1 receptors and SR2 is a selective ligand for CB2 receptors in our in vitro binding assays.

Cannabinoid receptors are seven trans-membrane receptors coupled to G proteins, specifically Gi/o, which negatively regulate adenylate cyclase. The ability of WIN to activate CB receptors and to functionally change the intracellular cAMP level was assessed in a cAMP accumulation assay using CHO K1 cells expressing human CB1 and HEK293 cells expressing human CB2 receptors. WIN inhibited forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation (EC50: 31.87 ± 0.05 nmol·L−1, n = 3 for hCB1, and 0.77 ± 0.36 nmol·L−1, n = 5 for hCB2 receptors) in cells expressing recombinant hCB1 and hCB2 receptors respectively. Similarly, WIN was a potent agonist in rat adenylate cyclase assays, showing an EC50 values of 21.82 ± 0.16 nmol·L−1, n = 5 for rCB1, and 1.28 ± 0.37 nmol·L−1, n = 4 for rCB2. However, in this assay, WIN showed partial agonist activity, with a maximum inhibition of 45%, n = 6 at 12.79 nmol·L−1 for rCB2 receptors. SR2 showed inverse agonist activity at hCB2 and rCB2 receptors in these cyclase assays but SR1 demonstrated no activity in functional assays. Taken together, these data show that WIN is a non-selective, full agonist for rCB1 and a partial agonist at rCB2 receptors in functional assays in vitro.

Systemic WIN administration and systemic CB antagonists on systemic WIN-induced anti-allodynia

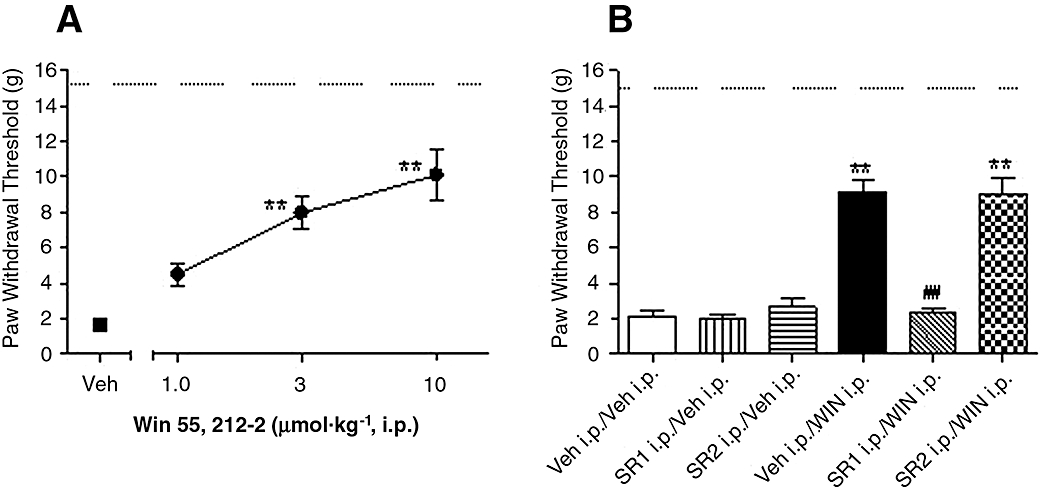

Hind paw injury resulted in the development of mechanical allodynia as indicated by a decreased PWT to a series of mechanical stimuli of calibrated von Frey filament 2 h post-incision (1.5 ± 0.1 g), compared with 15 g in non-injured paw (P < 0.01). WIN dose-relatedly reduced mechanical hypersensitivity, with 47 ± 6 and 63 ± 10% effect at 3 and 10 µmol·kg−1, compared with vehicle-treated animals 2 h following surgery [Figure 1A, F (3,19) = 18, P < 0.001, n = 6 per group].

Figure 1.

Effects of systemic WIN 55,212-2 (WIN) on skin incision-induced post-operative pain demonstrated as the increase of paw withdrawal threshold. (A) WIN (1, 3 and 10 µmol·kg−1) was injected i.p. in rats 90 min after surgery. (B) Reversal of WIN-induced analgesic efficacy by pretreatment with CB receptor antagonists, selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (SR1, 30 µmol·kg −1, i.p.) or selective CB2 receptor antagonist SR144528 (SR2, 10 µmol·kg−1, i.p.) was injected 15 min before the administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.). Mechanical allodynia was assessed 30 min following WIN treatment. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus vehicle (Veh) treated group, ##P < 0.01, SR1 i.p./WIN i.p. versus Veh i.p./WIN i.p. group, n = 6 per group. Dashed line: paw withdrawal threshold of non-injured paw. CB, cannabinoid.

In the absence of CB antagonists, 5 µmol·kg−1 WIN produced 55 ± 7% anti-allodynic effects (P < 0.01). Pretreatment with selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR1 (30 µmol·kg−1, i.p.), but not with the CB2 receptor antagonist SR2 (10 µmol·kg−1, i.p.), fully blocked WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.)-induced analgesic activity. Systemic administration of SR1 (30 µmol·kg−1) or SR2 (10 µmol·kg−1) alone produced no alteration of the PWT of the injured paw, compared with vehicle treated animals [Figure 1B, F (5,42) = 46, P < 0.001, n = 6–12 per group].

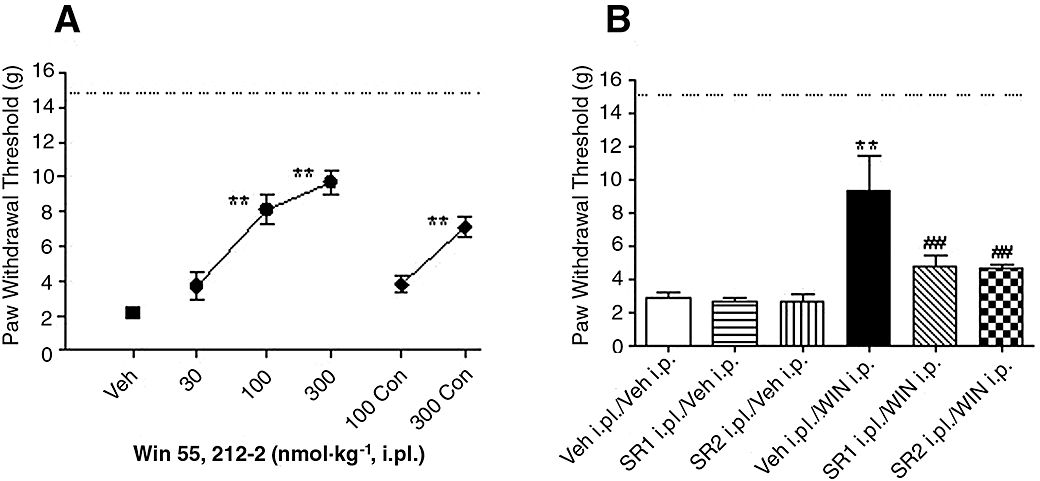

Peripheral effects of WIN and peripheral CB antagonists on systemic WIN-induced anti-allodynia

Peripheral injection of WIN (intraplantar; i.pl.) was designed to achieve localized application to the injured site, in doses ineffective at reducing post-operative pain when given systemically. Peripheral paw injection of WIN (30, 100, 300 nmol per paw, 90 min following surgery) reduced mechanical allodynia, by 46 ± 7% and 58 ± 6% at 100 and 300 nmol per paw,,respectively, compared with vehicle treated animals [Figure 2A, F (5,48) = 25, P < 0.001, n = 8–12 per group]. WIN applied to the contralateral side to the injury only produced anti-allodynic effects at 300 nmol per paw (38 ± 5%), which was less potent than the effects observed at the same dose when injected i.pl., at the site of injury (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Effects of peripheral injection of WIN 55,212-2 (WIN) on skin incision-induced post-operative pain demonstrated as the increase of paw withdrawal threshold. (A) WIN (30, 100, 300 nmol per paw) was intraplantarly (i.pl.) injected in rats 90 min after surgery, WIN (100, 300 nmol per paw) was also injected i.pl. to the contralateral (Con) non-injured paw in a separate group of animals. (B) Reversal of WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects by peripheral pretreatment with CB antagonists, selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (SR1, 150 nmol per paw) or selective CB2 receptor antagonist SR144528 (SR2, 150 nmol per paw) was injected i.pl. 15 min before the administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.). Mechanical allodynia was assessed 30 min after WIN treatment. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus vehicle (Veh) treated group, ##P < 0.01, SR1 i.pl./WIN i.p. or SR2 i.pl./WIN i.p. versus Veh i.p./WIN i.p. group, n = 6 per group. Dashed line: paw withdrawal threshold of non-injured paw. CB, cannabinoid.

Systemic administration of 5 µmol·kg−1 WIN alone decreased allodynia, by 53 ± 17% effects. Pretreatment with i.pl. SR1 or SR2 (150 nmol per paw) reversed WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.)-induced anti-allodynic effects. Intraplantar injection of SR1 or SR2 (150 nmol per paw) alone produced no alteration of PWT of the injured paw, compared with vehicle treated animals [Figure 2B, F (5,30) = 7.3, P < 0.001, n = 6 per group].

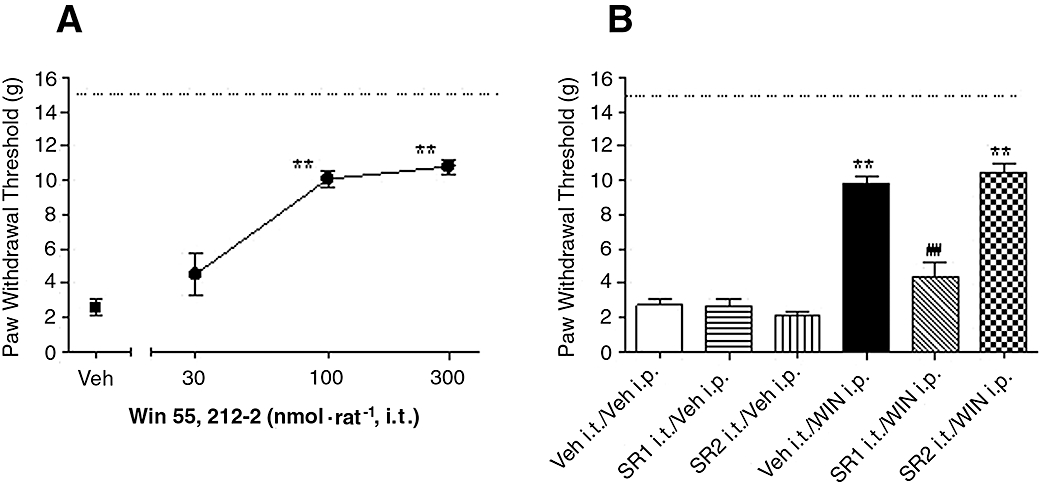

Spinal action of WIN and intrathecal CB antagonists on systemic WIN-induced anti-allodynia

Intrathecal (i.t.) application of WIN (30, 100, 300 nmol per rat, 90 min following surgery) reduced mechanical allodynia by 60 ± 4% and 66 ± 3%, at 100 and 300 nmol per rat respectively, compared with vehicle treated animals [Figure 3A, F (3,24) = 36, P < 0.001, n = 6–10 per group].

Figure 3.

Effects of spinal application of WIN 55,212-2 (WIN) on skin incision-induced post-operative pain demonstrated as the increase of paw withdrawal threshold. (A) WIN (30, 100, 300 nmol per rat) was intrathecally (i.t.) applied in rats 90 min after surgery. (B) Reversal of WIN-induced analgesic efficacy by spinal pretreatment with CB antagonists, selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (SR1, 150 nmol per rat) or selective CB2 receptor antagonist SR144528 (SR2, 150 nmol per rat) was intrathecally delivered 15 min before the administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.). Mechanical allodynia was assessed 30 min after WIN treatment. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus vehicle (Veh) treated group, ##P < 0.01, SR1 i.t./WIN i.p. versus Veh i.t./WIN i.p. group, n = 6 per group. Dashed line: paw withdrawal threshold of non-injured paw. CB, cannabinoid.

Systemic administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.) decreased allodynia, by 58 ± 3% in the absence of CB antagonist(s). Pretreatment with i.t. SR1 (150 nmol per rat), but not SR2 (150 nmol per rat), completely reversed WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.)-induced anti-allodynic effects. Intrathecal delivery of SR1 or SR2 (150 nmol per rat) alone produced no alteration of PWT of the injured paw, compared with vehicle treated animals [Figure 3B, F (5,33) = 56, P < 0.001, n = 6–8 per group].

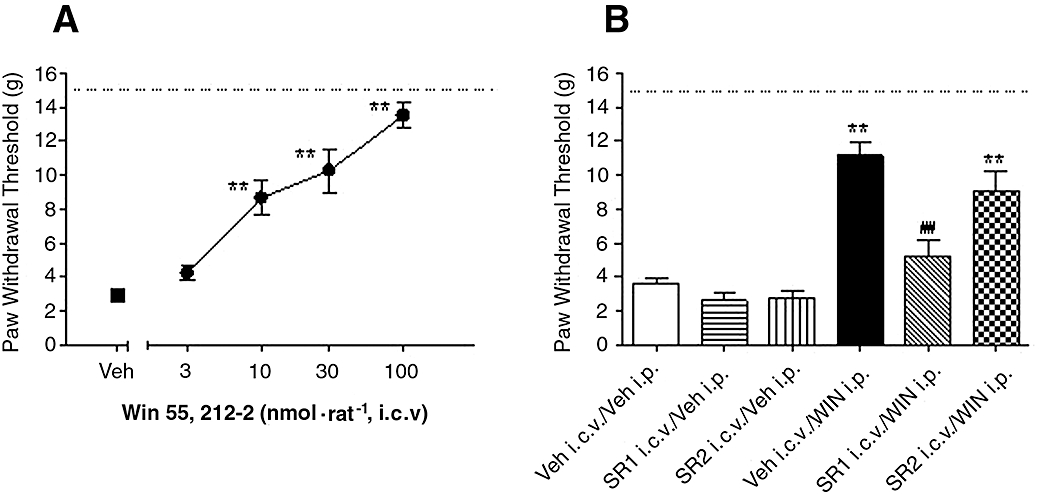

Supraspinal action of WIN and i.c.v. CB antagonists on systemic WIN-induced anti-allodynia

Intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusion of WIN (3, 10, 30, 100 nmol per rat, 90 min following surgery) dose-dependently inhibited mechanical allodynia, by 48 ± 8, 61 ± 11 and 88 ± 6% at 10, 30 and 100 nmol per rat, respectively, compared with vehicle treated animals [Figure 4A, F (4,25) = 27, P < 0.001, n = 6 per group].

Figure 4.

Effects of supraspinal infusion of WIN 55,212-2 (WIN) on skin incision-induced post-operative pain demonstrated as the increase of paw withdrawal threshold. (A) WIN (3,10, 30, 100 nmol per rat) was intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) infused in rats 90 min after surgery. (B) Reversal of WIN-induced analgesic efficacy by supraspinaly pretreatment with CB antagonists, selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (SR1, 150 nmol per rat) or selective CB2 receptor antagonist SR144528 (SR2, 150 nmol per rat) was i.c.v. infused 15 min before the administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.). Mechanical allodynia was assessed 30 min after WIN treatment. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus vehicle (Veh) treated group, ## P < 0.01, SR1 i.c.v./WIN i.p. versus Veh i.c.v./WIN i.p. group, n = 6 per group. Dashed line: paw withdrawal threshold of non-injured paw. CB, cannabinoid.

Systemic administration of WIN (5 µmol·kg−1) reduced allodynia, by 66 ± 8% in the absence of CB antagonist(s). Pretreatment with i.c.v. SR1 (150 nmol per rat) reversed WIN (5 µmol·kg−1, i.p.)-induced anti-allodynic effects, whereas WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects (48 ± 4%) were not significantly affected by pre-administration of SR2 (150 nmol per rat). Intracerebroventricular infusion of SR1 or SR2 (150 nmol per rat) alone produced no alteration of PWT of the injured paw, compared with vehicle treated animals [Figure 4B, F (5,39) = 15.8, P < 0.001, n = 6–10 per group].

CNS side effects of systemic WIN

Systemic administration of WIN (1, 3, 10 µmol·kg−1) reduced horizontal exploratory activity in naïve rats, with a maximal efficacy of 71 ± 10% at 10 µmol·kg−1[Figure 5A, F (3,20) = 37, P < 0.01, n = 8 per group]. Similarly, WIN reduced fall latency in the rotarod assay by 23 ± 8% and 64 ± 5% at 3 and 10 µmol·kg−1[Figure 5B, F (3,20) = 37, P < 0.01, n = 6 per group].

Figure 5.

Effects of systemic WIN 55,212-2 (WIN) on spontaneous horizontal exploratory behaviours and rotarod performance. (A) WIN (1, 3 and 10 µmol·kg−1) was i.p. administered in naïve rats 30 min before the assessment of horizontal exploratory activity. (B) WIN (1, 3 and 10 µmol·kg−1) was i.p. administered in naïve rats 30 min before the recording of fall latency from rotarod performance. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus vehicle (Veh) treated group, n = 6–8 per group.

Discussion

The current study is the first to demonstrate that the non-selective CB receptor agonist, WIN 55,212-2 (WIN), attenuates pain behaviour in a rat model of post-operative pain. WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects were mainly attributed to CB1 receptor activation, as pretreatment with the CB1 receptor antagonist SR1 by i.p., i.pl., i.t., and i.c.v. routes of administration prevented systemic WIN-induced analgesia, whereas the pretreatment with CB2 receptor antagonist SR2 prevented systemic WIN-induced analgesia only following i.pl. injection. Finally, WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects were not clearly separable from CNS adverse effects, as analgesic doses of WIN also reduced horizontal exploratory activity and rotarod performance.

The non-selectivity and affinity of WIN for the CB receptor subtypes, CB1 versus CB2, reported from the present study are consistent with those reported in the literature (Howlett et al., 2002; Yao et al., 2008), indicating that the in vivo effects of WIN could be mediated non-selectively via activation of both CB1 and CB2 receptors. Following i.p. injection, WIN produced dose-dependent anti-allodynic effects in the hind paw injury model of post-operative pain, with a maximal efficacy of 63% (10 µmol·kg−1). In agreement with our observation, systemic WIN has been shown to reduce mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain (Fox et al., 2001; Costa et al., 2004; Walczak et al., 2006), diabetic and/or paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain (Dogrul et al., 2004; Ulugol et al., 2004; Pascual et al., 2005), capsaicin-evoked hyperalgesia (Li et al., 1999), formalin-induced persistent pain (Tsou et al., 1996) and spinal cord injury-induced surgical pain (Hama and Sagen, 2007) in rodents. Although CBs have been shown to produce anti-nociceptive effects in several pre-clinical models of pain, a clinical trial of cannabis plant extract (Cannador) was terminated because of serious adverse events in patients receiving analgesic doses for post-operative pain (Holdcroft et al., 2006). To further understand the potential for CB-induced post-operative pain relief, the present study evaluated the role of CB receptor subtypes in WIN-induced analgesia in a well-described rat model of post-operative pain.

To examine the site(s) of action at different levels of the nociceptive pathways, we subsequently investigated the effects of systemically inactive doses of WIN following central administration. Intrathecal delivery of WIN into the spinal enlargement reduced mechanical allodynia, with a maximal efficacy of 66% at 300 nmol per rat. Intracerebroventricular infusion of WIN potently reduced mechanical allodynia at even lower doses, with 61% efficacy at 30 nmol per rat. These data, in addition to the blockade by i.t. and i.c.v. CB1 antagonist of the effects of systemic WIN, demonstrate that both the spinal cord and the brain play a role in the allodynic effects of W1N. The fact that local, i.c.v., infusion of WIN was 10-fold more potent than the local i.t. administration could suggest that the brain is a preferred site of action; it could also suggest that 30 min following i.c.v. administration, there is diffusion of the compound and activity at multiple sites that could synergize. Romero-Sandoval and Eisenach (2007) have reported that i.t. administration of another non-selective CB receptor agonist, CP 55,940, attenuated paw incision induced hypersensitivity, and this was prevented by co-application of both CB1 and CB2 receptor antagonists, supporting the possibility that both CB1 and CB2 receptors at the spinal cord level play an important role in nociceptive transmission following intrathecal administration of a non-selective agonist. These results contrast in part with the present findings that show that following systemic administration of a non-selective agonist, spinal CB1 but not CB2 receptors seemed to mediate the anti-allodynic effects observed in vivo. This difference could be due to the route of administration of the agonist and suggest that while CB2 does play a role when the agonist is directly injected into the spinal cord, following systemic administration, CB1 receptors are the major system responsible for the antiallodynic effects. In line with our result, i.t. application of WIN has been shown to suppress CFA-induced allodynia, carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia (Richardson et al., 1998a; Martin et al., 1999), capsaicin-induced thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia (Johanek et al., 2001), formalin-induced persistent nociceptive behaviours (Yoon and Choi, 2003; Kang et al., 2007), peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain (Fox et al., 2001; Lim et al., 2003) and penicillin-induced central pain in rodents (Kukushkin et al., 2006). In addition, i.c.v. infusion of WIN also inhibited thermal hyperalgesia in the tail-flick assay (Welch et al., 1995; Lichtman et al., 1996; Raffa et al., 1999).

A large body of evidence indicates that the anti-nociceptive effect of CBs is mediated via central sites of action. First, CB receptors are expressed abundantly in the spinal cord and brain, and activation of CB receptors can induce anti-nociceptive activity (Tsou et al., 1996; 1998; Johanek and Simone, 2005), whereas knock-down of CB receptors could enhance the pain response (Dogrul et al., 2002; Walker and Hohmann, 2005). Second, CB receptors are up-regulated in the spinal cord following sciatic nerve injury and CFA-induced inflammatory pain (Amaya et al., 2006), and WIN-induced analgesic efficacy is reduced when such up-regulation is reversed (Dogrul et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2003). Third, electrophysiological studies have shown that WIN inhibits responses of thalamic and spinal dorsal horn neurons to acute peripheral noxious thermal or mechanical stimuli (Martin et al., 1996; Hohmann et al., 1999b; Fox et al., 2001), as well as the wind-up response to prolonged noxious stimulation (Strangman and Walker, 1999). WIN also inhibits the formalin-induced c-fos expression in the spinal cord and thalamus (Martin et al., 1996; 1999; Tsou et al., 1996; Hohmann et al., 1999a) and capsaicin-induced peptide release in the spinal cord (Richardson et al., 1998a).

In addition to central modulation, recent anatomical and behavioural data have provided compelling evidence for a role of peripheral CB receptors in nociceptive transmission (Agarwal et al., 2007). In the present study, i.pl. injection of WIN reduced mechanical allodynia, with a maximal efficacy of 58% at 300 nmol per paw, demonstrating that post-operative pain can also be attenuated by the activation of CB receptors at the peripheral site of injury. Previous studies have demonstrated that i.pl. anandamide inhibits carrageenan or capsaicin-induced hyperalgesia and paw oedema (Richardson et al., 1998b; Amaya et al., 2006) and formalin-induced persistent pain (Calignano et al., 1998). Intra-plantar application of WIN also suppressed capsaicin and/or carrageenan-induced thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia (Li et al., 1999; Johanek et al., 2001; Nackley et al., 2003), and heat-injury induced thermal hyperalgesia (Johanek and Simone, 2004). In addition, i.pl. injection of WIN or application to the site of a peripheral nerve injury reduced mechanical and cold allodynia (Fox et al., 2001; Lever et al., 2007), and topical application of WIN produced analgesic activity in tail flick assay (Dogrul et al., 2003). Consistent with a peripheral site of action, CB receptors are localized to nerve fibres and cutaneous nociceptors (Agarwal et al., 2007; Lever et al., 2007), activation of these receptors inhibits excitatory calcium responses and reduces exocytosis of neuropeptides from these neurons (Ahluwalia et al., 2003) as well as their peripheral terminals stimulated in the skin (Ellington et al., 2002). Consequently, topical application of CBs to skin has a suppressive effect on the pro-inflammatory and pro-nociceptive efferent functions of C-fibre sensory neurons (Rukwied et al., 2003; Yesilyurt et al., 2003), whereas, peripheral knockout of CB receptors leads to a major reduction in the analgesia produced by systemically administered CBs (Agarwal et al., 2007). Collectively, our results suggest that CB receptors expressed in primary afferent neurons are also involved in nociceptive transmission of post-operative pain (Farquhar-Smith and Rice, 2003). Interestingly, contralateral paw application of WIN at 100 nmol per paw produced no anti-allodynic effects, whereas 300 nmol per paw revealed a weaker effect compared with ipsilateral injection, suggesting that diffusion after i.pl. injection may occur and produce some degree of systemic efficacy.

To explore the specific contribution of CB receptor subtypes at different levels of the nociceptive pathways in post-operative pain, the selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR1 or CB2 receptor antagonist SR2 were both systemically and locally applied prior to i.p. WIN administration. WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects were prevented by the pretreatment with i.p. SR1 but not i.p. SR2; pretreatment with i.t. or i.c.v. SR1, but not SR2, also prevented i.p. WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects, supporting the hypothesis that WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects are mediated via CB1 receptor activation, and such mediation is predominantly centrally mediated. It was previously reported that systemic pretreatment with SR1 antagonized systemic WIN-induced analgesia in neuropathic pain caused by sciatic nerve injury or paclitaxel toxicity (Pascual et al., 2005). In addition, the topical analgesic effects of WIN were blocked by systemic pretreatment with a selective CB1 receptor antagonist (AM 251) in the tail-flick test (Yesilyurt et al., 2003). Intrathecal delivery of SR1 reversed CP 55,940-induced attenuation of spinal neuronal sensitization (Johanek and Simone, 2005), blocked WIN-induced analgesia in capsaicin-hyperalgesia (Johanek et al., 2001) and abolished WIN-induced reversal of peripheral nerve injury-induced mechanical hyperalgesia (Fox et al., 2001). Taken together, these data show that the WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects are mediated via the activation of centrally located CB1 receptors. The dose of 5 µmol·kg−1 (2.13 mg·kg−1) of WIN was chosen for i.p. administration for all experiments of the action site(s), as this is an approximate ED50 value of analgesic efficacy from our systemic dose-response study. The dose of 150 nmol per rat of SR1 or SR2 were chosen for site application, which is about 20- to 60-fold lower than that used for systemic blockade (10 µmol·kg−1 for SR2, 30 µmol·kg−1 for SR1), as l WIN was 10- to 100-fold more potent given locally than when given by systemic routes. Higher doses SR1 or SR2 for central application were attempted without success due to limited solubility of these two compounds.

Our study also provides evidence that systemic WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects are partially peripherally mediated by both CB1 and CB2 receptors, as both CB1 and CB2 antagonists applied at the site of injury partially prevented i.p. WIN-induced anti-allodynic effects. Previous reports demonstrated that peripheral SR1 or SR2 administration reversed WIN-induced effect on mechanical hypersensitivity in nerve injury (Lever et al., 2007), and i.pl. co-application SR1 and/or SR2 blocked WIN-induced suppression of carrageenan-evoked Fos protein expression and pain behaviour (Nackley et al., 2003). These data provide direct evidence that a peripheral CB mechanism suppresses inflammation-evoked neuronal activity at the level of the spinal dorsal horn, suggesting that the peripheral anti-allodynic effects of CBs may be exploited for treatment of inflammatory pain states (Nackley et al., 2003; Gutierrez et al., 2007).

It is well-established that the analgesic properties of non-selective CB agonists are usually associated with undesired CNS side effects (Walker and Hohmann, 2005). The current study demonstrated that systemic WIN reduced horizontal exploratory activity and rotarod performance at systemic analgesic doses, suggesting that some of the anti-allodynic effects could be due to locomotor deficit. However, local administration of WIN at the site of injury and/or the central sites, at doses devoid of motor effects, also reduced post-operative pain behaviour, demonstrating that the ability of central and/or peripheral WIN administration to attenuate allodynia was not solely due to motor deficits. In supporting this notion, microinfusion of WIN at dose of approximately 60 nmol·kg−1 into different brain regions produced no alteration of locomotor activity in rats (Wegener et al., 2008). Furthermore, electrophysiological and immunocytochemical studies have demonstrated that WIN had antinociceptive properties without the potential disadvantage of motor impairment (Martin et al., 1996; Tsou et al., 1996).

These results demonstrate that both CB1 and CB2 receptors are involved in the peripheral anti-allodynic effect produced by WIN in a pre-clinical model of post-operative pain. In contrast, the centrally mediated anti-allodynic activity of WIN is due to the activation of CB1 but not CB2 receptors. Furthermore, the increased potency of WIN following i.c.v. administration suggests that its main site of anti-allodynic effect is CB1 receptors in the brain.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Abbott Laboratories.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- [3H]CP 55,940

[3H] (-)-cis-3-[2-hydroxy-4-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)phenyl]-trans-4-(3-hydroxypropyl)cyclohexanol)

- SR141716A (SR1)

5-(4-chloro-phenyl)-1-(2,4-dichloro-phenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid piperidin-1-ylamide

- SR144528 (SR2)

5-(4-chloro-3-methyl-phenyl)-1-(4-methyl-benzyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid ((1S,2S,4R)-1,3,3-trimethyl-bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-yl)-amide

- WIN 55,212-2

(R)-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-(4-morpholinylmethyl)pyrrolo[1,2,3-de)-1,4-benzoxazin-6-yl]-1-napthalenylmethanone

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, Amaya F, Constantin CE, Brenner GJ, et al. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia J, Urban L, Bevan S, Nagy I. Anandamide regulates neuropeptide release from capsaicin-sensitive primary sensory neurons by activating both the cannabinoid 1 receptor and the vanilloid receptor 1 in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2611–2618. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaya F, Shimosato G, Kawasaki Y, Hashimoto S, Tanaka Y, Ji RR, et al. Induction of CB1 cannabinoid receptor by inflammation in primary afferent neurons facilitates antihyperalgesic effect of peripheral CB1 agonist. Pain. 2006;124:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain. 1996;64:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)01441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan TJ, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Mechanisms of incisional pain. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calignano A, La Rana G, Giuffrida A, Piomelli D. Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids. Nature. 1998;394:277–281. doi: 10.1038/28393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa B, Colleoni M, Conti S, Trovato AE, Bianchi M, Sotgiu ML, et al. Repeated treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 reduces both hyperalgesia and production of pronociceptive mediators in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:4–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WJ. Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1980;20:441–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogrul A, Gardell LR, Ma S, Ossipov MH, Porreca F, Lai J. Knock-down' of spinal CB1 receptors produces abnormal pain and elevates spinal dynorphin content in mice. Pain. 2002;100:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogrul A, Gul H, Akar A, Yildiz O, Bilgin F, Guzeldemir E. Topical cannabinoid antinociception: synergy with spinal sites. Pain. 2003;105:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogrul A, Gul H, Yildiz O, Bilgin F, Guzeldemir ME. Cannabinoids blocks tactile allodynia in diabetic mice without attenuation of its antinociceptive effect. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington HC, Cotter MA, Cameron NE, Ross RA. The effect of cannabinoids on capsaicin-evoked calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release from the isolated paw skin of diabetic and non-diabetic rats. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:966–975. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar-Smith WP, Rice AS. A novel neuroimmune mechanism in cannabinoid-mediated attenuation of nerve growth factor-induced hyperalgesia. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:1391–1401. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200312000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A, Kesingland A, Gentry C, McNair K, Patel S, Urban L, et al. The role of central and peripheral Cannabinoid1 receptors in the antihyperalgesic activity of cannabinoids in a model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2001;92:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez T, Farthing JN, Zvonok AM, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG. Activation of peripheral cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors suppresses the maintenance of inflammatory nociception: a comparative analysis. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:153–163. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama A, Sagen J. Antinociceptive effect of cannabinoid agonist WIN 55,212-2 in rats with a spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Tsou K, Walker JM. Intrathecal cannabinoid administration suppresses noxious stimulus-evoked Fos protein-like immunoreactivity in rat spinal cord: comparison with morphine. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1999a;20:1132–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Tsou K, Walker JM. Cannabinoid suppression of noxious heat-evoked activity in wide dynamic range neurons in the lumbar dorsal horn of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1999b;81:575–583. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdcroft A, Maze M, Dore C, Tebbs S, Thompson S. A Multicenter Dose-escalation Study of the Analgesic and Adverse Effects of an Oral Cannabis Extract (Cannador) for Postoperative Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1040–1046. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200605000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral G, Casellas P, Devane WA, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanek LM, Simone DA. Activation of peripheral cannabinoid receptors attenuates cutaneous hyperalgesia produced by a heat injury. Pain. 2004;109:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanek LM, Simone DA. Cannabinoid agonist, CP 55,940, prevents capsaicin-induced sensitization of spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:989–997. doi: 10.1152/jn.00673.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanek LM, Heitmiller DR, Turner M, Nader N, Hodges J, Simone DA. Cannabinoids attenuate capsaicin-evoked hyperalgesia through spinal and peripheral mechanisms. Pain. 2001;93:303–315. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Kim CH, Lee H, Kim DY, Han JI, Chung RK, et al. Antinociceptive synergy between the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 and bupivacaine in the rat formalin test. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:719–725. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000255291.38637.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukushkin ML, Igon'kina SI, Churyukanov MV, Churyukanov VV, Bobrov MY, Bezuglov VV, et al. Role of cannabinoid receptor agonists in mechanisms of suppression of central pain syndrome. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2006;142:39–42. doi: 10.1007/s10517-006-0286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBuda CJ, Koblish M, Little PJ. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor agonist activity in the hindpaw incision model of postoperative pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;527:172–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever IJ, Pheby TM, Rice AS. Continuous infusion of the cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 to the site of a peripheral nerve injury reduces mechanical and cold hypersensitivity. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:292–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Daughters RS, Bullis C, Bengiamin R, Stucky MW, Brennan J, et al. The cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 mesylate blocks the development of hyperalgesia produced by capsaicin in rats. Pain. 1999;81:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Cook SA, Martin BR. Investigation of brain sites mediating cannabinoid-induced antinociception in rats: evidence supporting periaqueductal gray involvement. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim G, Sung B, Ji RR, Mao J. Upregulation of spinal cannabinoid-1-receptors following nerve injury enhances the effects of Win 55,212-2 on neuropathic pain behaviors in rats. Pain. 2003;105:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, Hohmann AG, Walker JM. Suppression of noxious stimulus-evoked activity in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus by a cannabinoid agonist: correlation between electrophysiological and antinociceptive effects. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6601–6611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06601.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, Loo CM, Basbaum AI. Spinal cannabinoids are anti-allodynic in rats with persistent inflammation. Pain. 1999;82:199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrirattanakul S, Ramakul N, Guerrero AV, Matsuka Y, Ono T, Iwase H, et al. Site-specific increases in peripheral cannabinoid receptors and their endogenous ligands in a model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2006;126:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Suplita RL, 2nd, Hohmann AG. A peripheral cannabinoid mechanism suppresses spinal fos protein expression and pain behavior in a rat model of inflammation. Neuroscience. 2003;117:659–670. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00870-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Batkai S, Kunos G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:389–462. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual D, Goicoechea C, Suardiaz M, Martin MI. A cannabinoid agonist, WIN 55,212-2, reduces neuropathic nociception induced by paclitaxel in rats. Pain. 2005;118:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos P, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptors and pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:569–611. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The endocannabinoid system: a drug discovery perspective. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogatzki EM, Gebhart GF, Brennan TJ. Characterization of Adelta- and C-fibers innervating the plantar rat hindpaw one day after an incision. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:721–731. doi: 10.1152/jn.00208.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffa RB, Stone DJ, Jr, Hipp SJ. Differential cholera-toxin sensitivity of supraspinal antinociception induced by the cannabinoid agonists delta9-THC, WIN 55,212-2 and anandamide in mice. Neurosci Lett. 1999;263:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Aanonsen L, Hargreaves KM. Antihyperalgesic effects of spinal cannabinoids. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998a;345:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Kilo S, Hargreaves KM. Cannabinoids reduce hyperalgesia and inflammation via interaction with peripheral CB1 receptors. Pain. 1998b;75:111–119. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sandoval A, Eisenach JC. Spinal cannabinoid receptor type 2 activation reduces hypersensitivity and spinal cord glial activation after paw incision. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:787–794. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264765.33673.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukwied R, Watkinson A, McGlone F, Dvorak M. Cannabinoid agonists attenuate capsaicin-induced responses in human skin. Pain. 2003;102:283–288. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal DM, Elmes SJ, Kendall DA, Chapman V. Intraplantar injection of anandamide inhibits mechanically-evoked responses of spinal neurones via activation of CB2 receptors in anaesthetised rats. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:404–411. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strangman NM, Walker JM. Cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 inhibits the activity-dependent facilitation of spinal nociceptive responses. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:472–477. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou K, Lowitz KA, Hohmann AG, Martin WJ, Hathaway CB, Bereiter DA, et al. Suppression of noxious stimulus-evoked expression of Fos protein-like immunoreactivity in rat spinal cord by a selective cannabinoid agonist. Neuroscience. 1996;70:791–798. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)83015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou K, Brown S, Sanudo-Pena MC, Mackie K, Walker JM. Immunohistochemical distribution of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;83:393–411. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulugol A, Karadag HC, Ipci Y, Tamer M, Dokmeci I. The effect of WIN 55,212-2, a cannabinoid agonist, on tactile allodynia in diabetic rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;371:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzano KJ, Tafesse L, Lee G, Harrison JE, Boulet JM, Gottshall SL, et al. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characterization of the cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist, GW405833, utilizing rodent models of acute and chronic pain, anxiety, ataxia and catalepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:658–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak JS, Pichette V, Leblond F, Desbiens K, Beaulieu P. Characterization of chronic constriction of the saphenous nerve, a model of neuropathic pain in mice showing rapid molecular and electrophysiological changes. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1310–1322. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JM, Hohmann AG. Cannabinoid mechanisms of pain suppression. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005:509–554. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Pettus M, Gao D, Phillips C, Scott Bowersox S. Effects of intrathecal administration of ziconotide, a selective neuronal N-type calcium channel blocker, on mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia in a rat model of postoperative pain. Pain. 2000;84:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener N, Kuhnert S, Thuns A, Roese R, Koch M. Effects of acute systemic and intra-cerebral stimulation of cannabinoid receptors on sensorimotor gating, locomotion and spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;198:375–385. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch SP, Thomas C, Patrick GS. Modulation of cannabinoid-induced antinociception after intracerebroventricular versus intrathecal administration to mice: possible mechanisms for interaction with morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:310–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Chronic catheterization of the spinal subarachnoid space. Physiol Behav. 1976;17:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao BB, Hsieh GC, Frost JM, Fan Y, Garrison TR, Daza AV, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of A-796260: a selective cannabinoid CB(2) receptor agonist exhibiting analgesic activity in rodent pain models. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:390–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao BB, Mukherjee S, Fan Y, Garrison TR, Daza AV, Grayson GK, et al. In vitro pharmacological characterization of AM1241: a protean agonist at the cannabinoid CB2 receptor? Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:145–154. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesilyurt O, Dogrul A, Gul H, Seyrek M, Kusmez O, Ozkan Y, et al. Topical cannabinoid enhances topical morphine antinociception. Pain. 2003;105:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon MH, Choi JI. Pharmacologic interaction between cannabinoid and either clonidine or neostigmine in the rat formalin test. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:701–707. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200309000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn PK, Brennan TJ. Intrathecal metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists do not decrease mechanical hyperalgesia in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1354–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CZ, Hsieh G, Ei-Kouhen O, Wilson SG, Mikusa JP, Hollingsworth PR, et al. Role of central and peripheral mGluR5 receptors in post-operative pain in rats. Pain. 2005;114:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]