Abstract

Background

Due to the osseous distribution of prostate cancer metastases, progression is more readily identified than response in prostate cancer clinical trials. As a result, there is an increased focus on progression free survival (PFS) as a phase II endpoint. PFS, however, is vulnerable to inter-study design variability. We sought to identify and quantify this variability and the resultant error in PFS across prostate cancer clinical trials.

Methods

We reviewed phase II clinical trials of cytotoxic agents in castrate metastatic prostate cancer over 5-years to evaluate the policies determining extent of disease and the definitions of disease progression. A simulation model was created to define the degree of error in estimating PFS in 3 hypothetical cohorts (median PFS of 12, 24, and 36 weeks) when the frequency of outcome assessments varies.

Results

Imaging policies for trial entry were heterogeneous, as were the type, timing, and indications for outcome assessments. In the simulation, error in the reported PFS varied according to the interval between assessments. The difference between the detected and the true PFS could vary as much as 6.4 weeks per cycle, strictly resulting from the variability of assessment schedules tested.

Conclusions

Outcome assessment policies are highly variable in phase II studies of castration-resistant prostate cancer patients, despite published guidelines designed to standardize authenticating disease progression. The estimated error in PFS can exceed 6 weeks per cycle, just due to variations in the assessment schedules. Comparisons of PFS times from different studies must be made with circumspection.

Keywords: prostate cancer, phase II clinical trials, outcome assessments, endpoints, progression-free survival

Introduction

The design of clinical trials to assess drug effects in prostate cancer poses unique challenges relative to other solid tumors. Metastases are primarily localized to bone, where changes in disease status are difficult to assess and the natural history is highly variable; in addition, post-therapy changes in PSA are not surrogates for clinical benefit.1,2 Consequently, classifying post-treatment radiographic or biochemical changes using traditional response categories is difficult. Although defining a treatment response in prostate cancer may be difficult, tumor progression is far easier to recognize. For example, bone scans may take months to show improvement with an active treatment, but new lesions seen on serial bone scintigraphy tend to reflect progressive disease. Similarly, although post-treatment changes in PSA are not surrogates for clinically relevant events, PSA rises are generally used as an indicator of disease progression.

It was these considerations that led the Prostate Cancer Working Group to shift the focus of clinical trials from measures of response to measures of progression in its latest Consensus Guidelines for phase II studies.3 Indeed, even in the phase III setting, trials are now being designed, conducted, and submitted for regulatory approval using progression-free survival (PFS) measures, rather than overall survival, as the primary endpoint. Unfortunately, the results have been disappointing, and no agent or approach to date has been successful in this context.

Significant errors can occur when assessing PFS that can lead investigators astray if these miscalculations are not recognized or accounted for. In particular, the endpoint itself is sensitive to the methods used to assess disease and the definition of progression used. Differences in the timing of disease assessments alone can give the appearance that 1 drug provides a longer PFS relative to another.4 The purpose of this study was to review the reported phase II trials of cytotoxic drugs in prostate cancer to demonstrate the frequency of such heterogeneity and, through simulation, construct a model to quantify the error in estimating PFS that this lack of uniformity creates.

Materials and Methods

Disease Assessment in Contemporary Clinical Trials of Cytotoxic Agents

To examine the evaluations used to determine disease extent at study entry and the timing of the assessments after treatment, a PubMed search (www.pubmed.gov) from February 2001 through February 2006 was performed using the following key words: prostate cancer, chemotherapy, cytotoxic, and phase II. Published trials reported in English were reviewed for the reported baseline extent of disease evaluation, the definition of disease progression for eligibility and trial termination, and the indication and the interval for repeating a specific test to determine treatment effects.

Estimating PFS Using Different Disease Assessment Intervals Post-Treatment

A simulation was performed to demonstrate the potential bias introduced when estimating PFS by assessing disease at different intervals. Three different reassessment schedules based on the frequency reported in the trials reviewed were used. In schedule A, patients were assessed for response every 6 weeks until week 48, and then in 6-month intervals for 2 additional years. In schedule B, patients were assessed for response every 8 weeks until week 48, and then in 6-month intervals for 2 additional years. In schedule C, assessments occurred every 12 weeks until week 48, and then in 6-month intervals for 2 additional years. Three hypothetical patient risk cohorts—rapid, intermediate, and slow progression—were generated to assess what degree the interaction between interval assessment and the rate of progression had on the estimated PFS. Median times to progression for these 3 cohorts were 12, 24, and 36 weeks. In total, there were 9 assessment schedule/risk group cohorts in the simulation.

For each cohort in the simulation, 100 progression times were generated from an exponential distribution. Because the median progression time fully specifies an exponential distribution within a risk cohort, the exponential distribution was the same; only the assessment schedule differed. The recorded PFS time was the upper value of the assessment interval. To determine the patient-specific assessment times, a uniform random variable (-2, 2 weeks) was added to each fixed assessment time, to simulate the real-life scenario that patients do not come for testing exactly on the date they were scheduled, rather they are assessed within 2 weeks of the scheduled visit. For example, a patient on schedule A (q 6 weeks) with a true progression time of 26 weeks was recorded as a failure in the neighborhood of 28 to 32 weeks. Within each assessment schedule/risk group simulation, the 100 progression times produced a Kaplan-Meier estimate of PFS. This simulation was replicated 1000 times, and the summaries from the Kaplan-Meier estimates of the 1000 replications are provided in the results.

Effect of the Post-Treatment Imaging Policy on Time to Progression

Three hypothetical patients about to start treatment on a clinical trial of a taxane that would be administered every 21 days were considered. Each met the criteria for radiographic progression but differed in the pattern of disease spread. The modality and the timing of post-treatment imaging used for each patient were specific for the baseline pattern of spread. Four policies were evaluated: performing both computed tomography (CT) and bone scans at fixed intervals; performing scans only if abnormal at baseline; performing a CT every other cycle and a bone scan every 4 cycles; and only performing follow-up bone scans for patients with no soft-tissue disease at baseline.

Results

A total of 59 trials were identified, of which 46 (78%) met the criteria for inclusion. Details of the trials are outlined in Table 1. Of the 13 trials excluded, 9 did not publish the timeline for radiographic and/or PSA assessments post-treatment, 2 were phase I/II, 1 focused solely on squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate, and 1 was initiated in the pre-PSA era. Among the 46 included trials, the primary endpoint was PSA decline in 28 (61%) of the trials, tumor response (defined as a response in either PSA or imaging) in 11 (24%) trials, and radiographic response in 3 (7%), while 1 (2%) used PSA and radiographic response as separate primary endpoints. Three (7%) trials used a palliative endpoint.

TABLE 1. Baseline Trial Population.

| Total number of trials | 59 |

|---|---|

| Total number of trials excluded | 13 |

| No published outcome assessment timeline, n (%) | 9 (15) |

| Phase I/II, n (%) | 2 (3) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma only, n (%) | 1 (2) |

| Pre-PSA era, n (%) | 1 (2) |

| Total number of trials for review | 46 |

| Primary endpoint, n (%) | 46 |

| PSA only | 28 (61) |

| Tumor response (PSA or radiographic) | 11 (24) |

| Radiographic only | 3 (7) |

| Palliative | 3 (7) |

| PSA and radiographic as separate endpoints | 1 (2) |

PSA indicates prostate-specific antigen.

Assessment of Disease Extent and Progression Criteria at Study Entry

Extent of disease evaluations required on enrollment was not consistent. Although all trials required progression of disease at study entry, the published requirement for documenting metastatic disease with imaging varied considerably among trials. Cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen and pelvis was either not specified or required in 22% (10 of 46). Fifteen percent (7 of 46) of the trials did not require a bone scan. Fourteen of 46 trials (30%) either did not require or specify any chest imaging at enrollment. Of the 32 trials that did specifying chest imaging requirement, chest radiograph (rather than chest CT) was the most common assessment in 78% (25 of 32).

The definition of progressive disease for trial enrollment was similarly disparate. Progression of measurable disease was defined as an increase in existing lesions in 11 studies (24%), a new lesion or an increase in existing lesion in 5 (11%), new lesions alone in 3 (7%), while the remaining 27 (59%) did not outline specific criteria. For bone disease, progression was defined as new lesions in 20 studies (43%) and worsening existing lesions in 19 studies (41%); progression was not defined in 6 studies (13%). For progression based on pre-therapy changes in PSA, the PSA Working Group Criteria were used for 10 studies (22%) and other criteria were used in 20 (43%), while 13 (28%) did not report the criteria used. Three studies (7%) did not use PSA progression criteria for eligibility.

Frequency and Indications for Post-Treatment Assessments

Soft tissue and bone

Considerable variation was found in the timing of follow-up assessments of soft tissue and bone metastases, as shown in Table 2. The specified reassessment interval ranged from 6 to 16 weeks for soft tissue and from 6 to 11 weeks for bone. The indications also varied as 28% of the trials (13 of 46) did not require a follow-up cross-sectional scan (CT or MRI) to assess for soft-tissue or visceral disease and 33% (15 of 46) did not require a follow-up bone scan unless clinically indicated or if the baseline study was negative.

TABLE 2. Phase II Trials – Policy for Imaging and PSA Reassessment.

| Trials (N=46) | Cycle Length (weeks) | Time to Reassessment (weeks) | Time to PSA Reassessment (weeks) | Time to Initial Response Assessment (weeks) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Bone Scan | Baseline CT/MRI | ||||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||||

| Cabrespine8 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 3 | NS |

| Boehmer9 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 3 | NS |

| Hussain10 | 3 | 6 | As indicated | 6 | As indicated | 3 | 6 |

| Olver11 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | NS | NS |

| Spicer12 | 3 | As indicated | As indicated | 9 | As indicated | 3 | NS |

| Carles-Galcerán13 | 3 | 6 (then 9) | 6 (then 9) | 6 (then 9) | 6 (then 9) | 6 (then 3) | 6 |

| Tolcher14 | 3 | 6* | 6* | 6* | 6* | 3 | NS |

| Berruti15 | 4 | 26 | 26 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 9 |

| Oudard16 | 3 | 9* | 9* | 6* | 6* | 3 | NS |

| Galsky17 | 3 | 12 | As indicated | 12 | As indicated | 3 | NS |

| Senzer18 | 4 | As indicated | As indicated | 8 | As indicated | 2 | 8 |

| Font19 | 3 | As indicated | As indicated | 9 | 63 | 3 | NS |

| Beer20 | 4 | As indicated | As indicated | 8 | As indicated | 4 | NS |

| Latif21 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| Berry22 | 4 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| Dahut23 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| Ferrero24 | 8 | 8 | As indicated | 8 | As indicated | 4 | NS |

| Bernardi25 | 3 | 9 | As indicated | 9 | As indicated | 3 | NS |

| Borrega26 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 3 | NS |

| Vaughn27 | 4 | 8 × 1 y (then 84) | 8 × 1 y (then 84) | 8 × 1 y (then 84) | 8 × 1 y (then 84) | 4 | NS |

| Albrecht28 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 |

| Oh29 | 3 | 9* | 9* | 9* | 9* | 3 | NS |

| Hellerstedt30 | 4 | 13 | As indicated | 13 | As indicated | 4 | NS |

| Koletsky31 | 3 | As indicated | As indicated | 3 | 3 | 3 | NS |

| Smith32 | 3 | 9 | As indicated | 9 | As indicated | 3 | NS |

| Odrazka33 | 2 | 12 | As indicated | 8 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| Samelis34 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | NS |

| Robles35 | 1 w × 12 cycles then 2 w | 12 | As indicated | 6 × 2 then 12 × 1 y | As indicated | 4 w × 3 then 13 w | NS |

| Petrioli36 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| Tralongo37 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 3 | NS |

| Daliani38 | 4 | At max PSA decline + POD | At max PSA decline + POD | At max PSA decline + POD | At max PSA decline + POD | 4 | NS |

| Beer39 | 8 | As indicated | As indicated | 8 | As indicated | 4 | NS |

| Sinbaldi40 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | NS |

| Vaishampayan41 | 4 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 3 | NS |

| Bex42 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 3 | NS |

| Urakami43 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| Klein44 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| McMenemin45 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | NS |

| Sweeney46 | 1 w × 8 cycles then 2 w | 12 | 12 | 8 | As indicated | 4 | NS |

| Levine47 | 3 | Arm I: 9 Arm II: 12 | Arm I: 9 Arm II: 12 | Arm I: 9 Arm II: 12 | Arm I: 9 Arm II: 12 | 3 | NS |

| Beer48 | 8 | 8 | As indicated | 8 | As indicated | 4 | NS |

| Sitki Copur49 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 3 | NS |

| Berry50 | 8 | 24 | 24 | 8 | 8 | 8 | NS |

| Recchia51 | 4 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 4 | NS |

| Saverese52 | 3 | 6 (then 13) | 6 (then 13) | 6 (then 13) | 6 (then 13) | 3 | NS |

| Oudard53 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 3 |

CT indicates computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NS, not specified; POD, progression of disease; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Investigator discretion as to the choice of CT/MRI and/or bone scan for assessments.

PSA

The interval for PSA assessments ranged from 1 to 8 weeks, but was determined in 38 (83%) of the trials every 3 to 4 weeks. PSA assessment corresponded with the start of a new cycle of therapy in 34 trials (74%). The remaining trials with measurement intervals outside of the 3 or 4 week range evaluated agents with treatment cycles that were either shorter than 3 weeks or longer than 4 weeks.

Definitions of Progression for Study Termination

Of the 46 studies examined, the only criteria specified for progression in bone was “disease progression” in 19 (41%), while an additional 6 (13%) did not specify a definition. Of the remaining 21, 20 (43% of the total) specified a requirement for new lesions, while 1 allowed either new lesions or an increase in existing lesions. For soft-tissue disease, 8 (17%) used the outcome criteria defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), 27 (59%) used the criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO), 4 used the criteria of the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG), 2 (4%) used other criteria, and 5 (11%) did not specify a definition. Biochemical progression based on PSA changes was defined using the PSA Working Group Criteria in 26 (57%) and “other” criteria in the remaining 20 (43%).

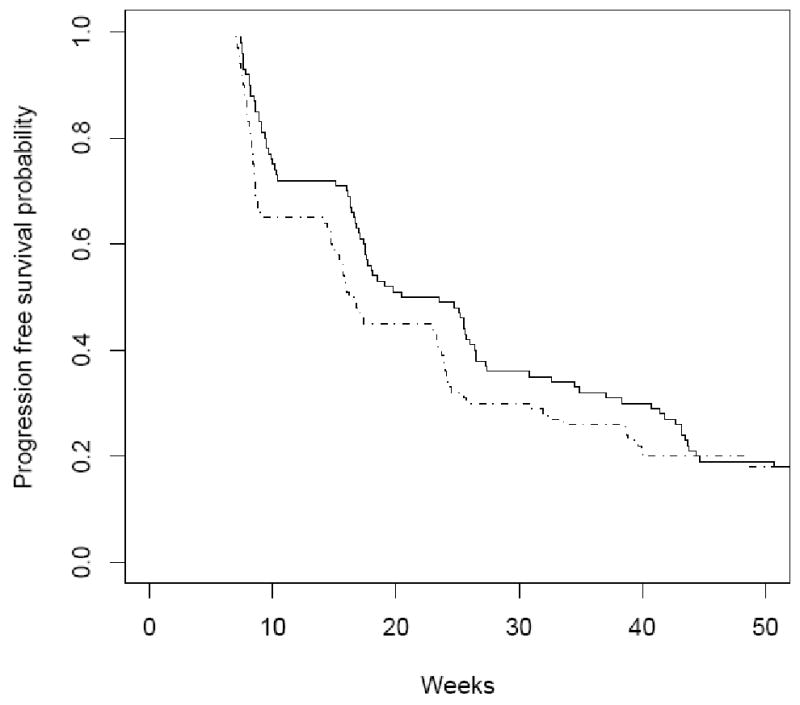

Bias in PFS Resulting From Changes in the Assessment Interval

To assess the unintended consequences of variable assessment times on PFS, a total of 9 schedule and risk group cohort combinations were created. They were based on the 3 assessment schedules (every 6, 8, or 12 weeks) and the 3 patient risk cohorts with median PFS of 12, 24, or 36 weeks. A summary of the Kaplan-Meier PFS under the hypothetical scenario that progression assessments were recorded daily (representing a “true” PFS in the model) was also added. Table 3 summarizes these results. The different assessment schedules between groups had a significant effect on the estimated PFS time. For example, when the true median PFS was 12 weeks, the information lag inherent in lengthening the assessment times resulted in a reporting of increased PFS at 15.6, 16.6, and 18.7 weeks for the q6, q8, and q12 week schedules, respectively. The reported PFS quantile differed from the “true” PFS quantile based on daily assessments by as much as 6.4 weeks when a q12 week assessment schedule was used. When the evaluation of the progression event is based on a periodic imaging schedule or PSA measurement, the recorded event time of the event will always be greater than the true event time, an effect that is most pronounced early in the treatment time course (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3. Change in Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Reported PFS When the Timing of Assessments for Progression Varies.

| Actual Median PFS | Percentile | Kaplan-Meier Quantile Estimates of Reported PFS (weeks) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Assessment | Q6 Week Assessment | Q8 Week Assessment | Q12 Week Assessment | ||

| 12 weeks | 75th Percentile | 5.2 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| 50th Percentile (median) | 12.3 | 15.6 | 16.6 | 18.7 | |

| 25th Percentile | 24.5 | 27.7 | 28.7 | 30.8 | |

| 24 weeks | 75th Percentile | 10.4 | 13.5 | 14.8 | 15.1 |

| 50th Percentile (median) | 24.6 | 27.4 | 28.4 | 30.2 | |

| 25th Percentile | 48.9 | 57.5 | 58.0 | 58.6 | |

| 36 weeks | 75th Percentile | 15.5 | 18.2 | 19.0 | 21.9 |

| 50th Percentile (median) | 36.7 | 38.5 | 39.5 | 41.3 | |

| 25th Percentile | 73.2 | 78.1 | 78.1 | 98.2 | |

PFS indicates progression-free survival.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of assessment schedule on reported progression-free survival.

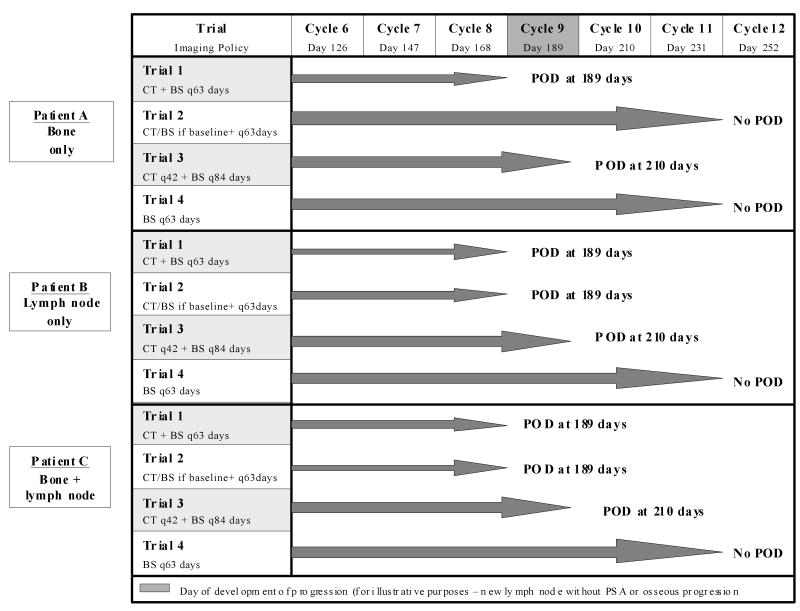

Impact of Different Imaging Policies on the Determination of Progression-Free Survival

Figure 2 illustrates 3 hypothetical patients who are about to enroll on a phase II clinical trial of a cytotoxic agent that will be administered every 21 days. Each meets the eligibility requirement of progression by PSA, but differs in the sites of disease spread by scan. Patient A has osseous disease only with no evidence of soft-tissue or visceral disease; patient B has significant lymphadenopathy but no osseous disease; and patient C has both bone disease and lymphadenopathy. For this example we assume that each patient's disease will progress by developing a new pelvic lymph node that meets the criteria for progression as defined by RECIST on day 189 (6.3 months), the median time to progression on SWOG 99-16,5 with no evidence of progression by PSA or by bone scan. The 4 imaging policies illustrated were derived from those used in the trials detailed in Table 2. Note how radiographically evident progression will be captured at different times depending on the extent of disease at baseline and as well as the imaging schema for each trial. This difference is seen both across trials with a “constant” patient as well as in the same trial with 3 patients having different distributions of disease.

FIGURE 2.

An example of how time to progression can vary based on timing and indication for imaging on clinical trial. Disease progression will be detected at different times depending on the extent of disease at baseline and as well as the imaging schema for each trial. This difference is seen both across trials with a “constant” patient as well as in the same trial with 3 patients having different distributions of disease. BS indicates bone scan; CT, computed tomography of chest, abdomen, and pelvis; POD, progression of disease; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Discussion

Phase II clinical trials in prostate cancer are focused increasingly on PFS endpoints because changes in bone and PSA—the primary manifestations of the disease—cannot be measured accurately by traditional response criteria. It follows that the results of such trials would be highly sensitive to the modalities used to evaluate disease status both before and after treatment, and the frequency with which such assessments are performed. In this study, we showed significant variation in the type, timing, and frequency of disease assessments to define distribution of disease, eligibility, and treatment effects. Using a model, we showed the bias that the frequency of outcome assessments can have on reported PFS. These factors undermine the reliability of the PFS endpoint and the ability to inferentially compare outcomes between trials.

The disparity in assessing disease at study entry was most surprising in that 22% of the reported trials did not specify abdominal and pelvic imaging, 15% did not require a bone scan, despite the high prevalence of osseous metastases in this patient group, and 30% percent of the trials reviewed did not specify or require chest imaging for study entry. The lack of consistency in defining disease progression at study entry was similarly worrisome, and in particular that criteria for progression were not specified for measurable disease in 57% and for bone in 13% of studies. Also notable was the inconsistency of the use of PSA, as 28% of the trials did not report the criteria used and only 22% of the trials used the PSA Working Group criteria.6

This study also demonstrates variation in the frequency of performing disease assessments following treatment and the policies for their use. Notably, disease extent in bone and soft tissue were assessed at different time points from each other and from PSA. It is not surprising that PSA determinations were performed more frequently than imaging. These intervals were generally shorter (every 3-4 weeks) than those for radiographic assessment times (every 6–25 weeks). However, given that progression is a continuous process, trials that defined PFS by PSA alone (61% of the reported studies), PSA or radiographic progression (24%), or radiographic progression only (7%) will give disparate results independent of the study treatment, with PSA-based PFS times being the shortest. By our model, median PFS might be overestimated by as much as 6.4 weeks in rapidly progressing patients purely as a function of the imaging intervals or discordance between the frequency of PSA assessments and radiographic assessments. Recognizing that the “true” PFS is a research-only construct, as daily imaging is not routinely performed, it is important to acknowledge that even the 3 week error in PFS that results from imaging every 12 weeks rather than every 6, aggregates with each cycle.

Finally, the reliability of the PFS endpoint is diluted by variations in the policy for what types of scanning were required. One third of the studies did not require repeat soft tissue or bone imaging if disease was not present in these locations at the time of study entry. Disease developing in a particular site might be missed simply because the test required to detect spread to that site was not performed. This factor alone could result in a failure to detect progression.

Some, but not all, of this bias can be reduced by using randomized designs in which the same baseline and follow-up disease assessments are performed at the same predefined intervals. Randomization and the choice of an overall survival endpoint do not completely negate the bias introduced by variable assessment schedules. The skew manifest by these variations in trial design is even more insidious in phase III studies. Patients in phase III studies receive therapy until they progress, and if the 2 arms of a phase III trials have different assessment schedules, patients will be declared progressors at different times, and receive different amounts of therapy. Even when two arms have identical assessment intervals, therapies that are more toxic and induce treatment delays then delay outcome assessments, as shown in Figure 3. The result is that a more toxic therapy appears to prolong PFS when it is simply an artifact of the timing of evaluations. Such considerations will need to be scrutinized with even greater care given that some phase III studies are now using PFS as a primary endpoint.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of a delay in time to outcome assessment in a randomized trial. Drugs A and B are represented by the dashed and solid lines, respectively. Both treatment groups are scheduled to have outcome assessments every 8 weeks; however, Drug B has an average delay of 5 days at each assessment time. Both groups have an actual median progression-free survival (PFS) of 18 weeks; however, the reported PFS of Drug B is clearly better, only because of the increased time to each assessment.

The recently updated consensus guidelines for phase II clinical trials in castrate metastatic disease have defined the minimum baseline studies that should be performed, as well as a policy for uniform post-treatment assessments.7 The updated guidelines specifically address the issue of authenticating disease progression and maintaining uniformity in both the methods and timing of disease assessments. Recommendations include radiographic imaging the chest, abdomen, and pelvis for soft-tissue disease in all patients at baseline, in addition to bone scintigraphy; distinguishing visceral, nodal, and bone index lesions and assessing each independently; discarding early tumor assessments and performing assessments at intervals of at least 12 weeks; and advocating that disease progression be defined radiographically or symptomatically rather than biochemically. The field does have, therefore, a standard -- the issue is one of adherence.

If these guidelines are not adopted, comparisons between trials will introduce bias that will continue to impede the drug development process. As the field stands now, however, while PFS is a more appropriate endpoint for prostate cancer than traditional response criteria, comparisons between studies using PFS as an endpoint should be approached with a critical eye and caution, and that PFS is not a surrogate for survival in prostate cancer. Such comparisons can be misleading unless the definitions of progression for enrollment, the criteria for treatment discontinuation, the types of evaluations used, and the schedules of assessments are not only defined, but are uniform.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: 5-T32-CA09207, K23 CA102544, P50 CA92629 (SPORE), Department of Defense, Prostate Cancer Foundation

Footnotes

Disclaimers: None

References

- 1.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scher HI, Morris MJ, Kelly WK, Schwartz LH, Heller G. Prostate cancer clinical trial end points: “RECIST”ing a step backwards. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5223–5232. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group (PCWG2) J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4487. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panageas KS, Ben-Porat L, Dickler MN, Chapman PB, Schrag D. When you look matters: the effect of assessment schedule on progression-free survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:428–432. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bubley GJ, Carducci M, Dahut W, et al. Eligibility and response guidelines for phase II clinical trials in androgen-independent prostate cancer: recommendations from the PSA Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3461–3467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, et al. The Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group (PCCTWG) conensus criteria for phase II clinical trials for castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol, ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. 2007;25(18 suppl):249s. Abstract 5057. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrespine A, Guy L, Khenifar E, et al. Randomized phase II study comparing paclitaxel and carboplatin versus mitoxantrone in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Urology. 2006;67:354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehmer A, Anastasiadis AG, Feyerabend S, et al. Docetaxel, estramustine and prednisone for hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a single-center experience. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:4481–4486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain M, Tangen CM, Lara PN, Jr, et al. Ixabepilone (epothilone B analogue BMS-247550) is active in chemotherapy-naive patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial S0111. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8724–8729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olver I, Keefe D, Myers M. Phase II study of prolonged ambulatory infusion carboplatin and oral etoposide for patients progressing through hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. Intern Med J. 2005;35:405–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spicer J, Plunkett T, Somaiah N, et al. Phase II study of oral capecitabine in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:364–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carles Galceran J, Bastus Piulats R, Martin-Broto J, et al. A phase II study of vinorelbine and estramustine in patients with hormone-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2005;7:66–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02710012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolcher AW, Chi K, Kuhn J, et al. A phase II, pharmacokinetic, and biological correlative study of oblimersen sodium and docetaxel in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3854–3861. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berruti A, Fara E, Tucci M, et al. Oral estramustine plus oral etoposide in the treatment of hormone refractory prostate cancer patients: a phase II study with a 5-year follow-up. Urol Oncol. 2005;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oudard S, Banu E, Beuzeboc P, et al. Multicenter randomized phase II study of two schedules of docetaxel, estramustine, and prednisone versus mitoxantrone plus prednisone in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3343–3351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galsky MD, Small EJ, Oh WK, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of the epothilone B analog ixabepilone (BMS-247550) with or without estramustine phosphate in patients with progressive castrate metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1439–1446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senzer N, Arsenau J, Richards D, Berman B, MacDonald JR, Smith S. Irofulven demonstrates clinical activity against metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer in a phase 2 single-agent trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:36–42. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000139019.17349.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Font A, Murias A, Arroyo FR, et al. Sequential mitoxantrone/prednisone followed by docetaxel/estramustine in patients with hormone refractory metastatic prostate cancer: results of a phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:419–424. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beer TM, Garzotto M, Katovic NM. High-dose calcitriol and carboplatin in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:535–541. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000136020.27904.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latif T, Wood L, Connell C, et al. Phase II study of oral bis (aceto) ammine dichloro (cyclohexamine) platinum (IV) (JM-216, BMS-182751) given daily × 5 in hormone refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:79–84. doi: 10.1023/B:DRUG.0000047109.76766.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry WR, Hathorn JW, Dakhil SR, et al. Phase II randomized trial of weekly paclitaxel with or without estramustine phosphate in progressive, metastatic, hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;3:104–111. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahut WL, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, et al. Randomized phase II trial of docetaxel plus thalidomide in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2532–2539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrero JM, Foa C, Thezenas S, et al. A weekly schedule of docetaxel for metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Oncology. 2004;66:281–287. doi: 10.1159/000078328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernardi D, Talamini R, Zanetti M, et al. Mitoxantrone, vinorelbine and prednisone (MVD) in the treatment of metastatic hormonoresistant prostate cancer—a phase II trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2004;7:45–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borrega P, Velasco A, Bolanos M, et al. Phase II trial of vinorelbine and estramustine in the treatment of metastatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:32–35. doi: 10.1016/S1078-1439(03)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaughn DJ, Brown AW, Jr, Harker WG, et al. Multicenter Phase II study of estramustine phosphate plus weekly paclitaxel in patients with androgen-independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:746–750. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albrecht W, Van Poppel H, Horenblas S, et al. Randomized Phase II trial assessing estramustine and vinblastine combination chemotherapy vs estramustine alone in patients with progressive hormone-escaped metastatic prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:100–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh W, Halabi S, Kelly WK, et al. A phase II study of estramustine, docetaxel, and carboplatin (EDC) with G-CSF support in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC): CALGB 99813. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:195a. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellerstedt B, Pienta KJ, Redman BG, et al. Phase II trial of oral cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and diethylstilbestrol for androgen-independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:1603–1610. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koletsky AJ, Guerra ML, Kronish L. Phase II study of vinorelbine and low-dose docetaxel in chemotherapy-naive patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer J. 2003;9:286–292. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith DC, Chay CH, Dunn RL, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel, estramustine, etoposide, and carboplatin in the treatment of patients with hormone-refractory prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:269–276. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odrazka K, Vaculikova M, Petera J, et al. Bi-weekly epirubicin, etoposide and low-dose dexamethasone for hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2003;10:387–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samelis GF, Skarlos D, Bafaloukos D, et al. The combination of estramustine and mitoxantrone in hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a phase II feasibility study conducted by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group. Urology. 2003;61:1211–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robles C, Furst AJ, Sriratana P, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine with low dose prednisone in the treatment of hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:885–889. doi: 10.3892/or.10.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrioli R, Pozzessere D, Messinese S, et al. Weekly low-dose docetaxel in advanced hormone-resistant prostate cancer patients previously exposed to chemotherapy. Oncology. 2003;64:300–305. doi: 10.1159/000070285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tralongo P, Bollina R, Aiello R, et al. Vinorelbine and prednisone in older cancer patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. A phase II study. Tumori. 2003;89:26–30. doi: 10.1177/030089160308900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daliani DD, Assikis V, Tu SM, et al. Phase II trial of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone in the treatment of androgen-independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:561–567. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beer TM, Eilers KM, Garzotto M, Egorin MJ, Lowe BA, Henner WD. Weekly high-dose calcitriol and docetaxel in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:123–128. doi: 10.1200/jco.2003.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinibaldi VJ, Carducci MA, Moore-Cooper S, Laufer M, Zahurak M, Eisenberger MA. Phase II evaluation of docetaxel plus one-day oral estramustine phosphate in the treatment of patients with androgen independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1457–1465. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaishampayan U, Fontana J, Du W, Hussain M. An active regimen of weekly paclitaxel and estramustine in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;60:1050–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bex A, Otto T, Lummen G, Rubben H. Phase II study of repeated single 24-hour infusion of low-dose 5-fluorouracil for palliation in symptomatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Urol Int. 2002;69:273–277. doi: 10.1159/000066118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urakami M, Igawa M, Kikuno N, et al. Combination chemotherapy with paclitaxel, estramustine, and carboplatin for hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Urol. 2002;168:2444–2450. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64164-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klein CE, Tangen CM, Braun TJ, et al. SWOG-9510: evaluation of topotecan in hormone refractory prostate cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Prostate. 2002;52:264–268. doi: 10.1002/pros.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McMenemin R, Macdonald G, Moffat L, Bissett D. A phase II study of caelyx (liposomal doxorubicin) in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate: tolerability and efficacy modification by liposomal encapsulation. Invest New Drugs. 2002;20:331–337. doi: 10.1023/a:1016225024121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sweeney CJ, Monaco FJ, Jung SH, et al. A phase II Hoosier Oncology Group study of vinorelbine and estramustine phosphate in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:435–440. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine EG, Halabi S, Roberts JD, et al. Higher doses of mitoxantrone among men with hormone-refractory prostate carcinoma: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Cancer. 2002;94:665–672. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beer TM, Pierce WC, Lowe BA, Henner WD. Phase II study of weekly docetaxel in symptomatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1273–1279. doi: 10.1023/a:1012258723075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sitka Copur M, Ledakis P, Lynch J, et al. Weekly docetaxel and estramustine in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:16–21. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berry W, Dakhil S, Gregurich MA, Asmar L. Phase II trial of single-agent weekly docetaxel in hormone-refractory, symptomatic, metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:8–15. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Recchia F, Sica G, De Filippis S, Rosselli M, Pompili PL, Rea S. Phase II study of epirubicin, mitomycin C, and 5-fluorouracil in hormone-refractory prostatic carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:232–236. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savarese DM, Halabi S, Hars V, et al. Phase II study of docetaxel, estramustine, and low-dose hydrocortisone in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a final report of CALGB 9780. Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2509–2516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oudard S, Caty A, Humblet Y, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:847–852. doi: 10.1023/a:1011141611560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]