Abstract

Background:

Posterior capsule opacification is one of the most frequent adverse events following cataract surgery. This manuscript reports the lifetime cost of complications linked to posterior capsule opacification using three types of intraocular lens with square edges.

Methods:

Costs were estimated from a retrospective study of patients who underwent cataract surgery and data from the literature. The lenses studied were hydrophobic acrylic (SA60AT and AR40E) and hydrophilic acrylic (XL-Stabi) lenses with square edges. The frequency of Nd-Yag laser capsulotomies after 4 years’ survival was estimated by two methods: the first involved linear adjustment of the rate at 5 and 6 years follow-up and then application of a constant rate after 6 years; the second involved linear adjustment after 5 years follow-up. The economic perspective was that of the French Sickness Fund.

Results:

After 3 years’ follow-up the percentage of patients who had not undergone laser Nd-Yag capsulotomy was 86.9% with SA60AT, 76.6% with AR40E and 54.6% with XL-Stabi lenses (p < 0.001). The total cost of capsulotomy and management of complications per patient lifetime was estimated to be €90.5 for SA60AT, €189.5 for AR40E and €288.0 for XL-Stabi lenses by the first extrapolation method. With the second method of extrapolation the costs were €94.8, €200.0 and €300.2, respectively.

Interpretation:

Lower costs for cataract surgery and management of related complications were observed with the two hydrophobic acrylic lenses; the lowest costs were observed with SA60AT lenses as they were associated with fewer Nd-Yag laser capsulotomies.

Keywords: cataract surgery, Nd-Yag laser, capsulotomy, adverse event, cost, budget impact

Introduction

The most frequent postsurgical complication of cataract surgery is posterior capsule opacification (PCO),1 which affects at least 20% of patients 3 years after surgery and around 38% 9 years after.2 When PCO becomes severe and affects the visual acuity of the patient, treatment by laser neodymium-Yag (Nd-Yag) is carried out.3

Secondary effects of laser-Yag capsulotomies are generally rare and transient, except for the formation of Elschnig pearls and elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP). The increase in IOP affects 4% to 7% of patients, particularly those with ocular comorbidities such as glaucoma, strong myopia or aphakia.4–5 Kato et al6 observed an increased rate of formation of Elschnig pearls after capsulotomy in 47.6% of the eyes, 12 months after capsulotomy. Formation of these pearls required a second operation in approximately 1/3 of eyes affected. According to Kurosaka,7 69.2% of the eyes developed Elschnig pearls during the 32.1 months post laser Nd-Yag follow-up.

The other secondary effects of cataract surgery generally affect less than 3% of patients. Rollin et al8 observed several cases of transient ocular hypertension and uveitis, and a single case of cystoid macular edema (CMO) after Nd-Yag laser. Boschi et al9 reported an incidence of CMO of 3.1%, an elevation of IOP in 11.9% and alteration of the lens in 27%.

Retinal damage after capsulotomy is a rare event. According to Javitt et al10 the risk of retinal detachment was 3.9 times higher (CI 95%: 2.89−5.25) in patients who had capsulotomy. The risk of retinal tearing was 2.24 times higher in patients who had capsulotomy.

In a recent study, Billotte and Berdeaux developed a Markov model to evaluate the frequency of complications following capsulotomy using data from the literature.11 If the intraocular lens (IOL) is replaced to reduce the frequency of laser Nd-Yag capsulotomies from 10% to 2.5%, 1201 detachments of the retina, 1201 CMO, 1342 cases of glaucoma and 5882 increases in IOP per year would be avoided per 400,000 subjects undergoing cataract surgery per year during the 3 years post surgery.

The costs linked to cataract surgery include insertion of the IOL but also costs linked to management of complications, including the cost of capsulotomies and related secondary effects. The frequency of capsulotomy depends mainly on the type of lens inserted. This analysis compared the costs over the lifetime of the patient after cataract surgery using three types of lens with square edges.

Materials

This economic analysis was performed from the perspective of the French Sickness Fund. It was based on the results of a retrospective analysis of patients picked up at random implanted with square edge IOLs. These clinical results were extrapolated to the entire life of the cohorts to allow calculation of the lifetime costs for the population.

Study plan

This retrospective, multicentric study was carried out in France by 10 ophthalmology centers. IOLs studied all had square edges: AcrySof® SA60AT (Alcon), AR40E (Advanced Medical Optics) and XL-Stabi (Zeiss-Ioltech). SA60AT and AR40E are hydrophobic acrylic lenses and XL-Stabi is a hydrophilic acrylic lens. The results of the multicentric retrospective study have been described in a previous publication.12 767 eyes treated with SA60AT (n = 250), AR40E (n = 254), or XL-Stabi (n = 263) were analyzed. After 3 years’ follow-up the proportions of patients who had not received Nd-Yag laser treatment were 86.9% with SA60AT, 76.6% with AR40E, and 54.6% with XL-Stabi (p < 0.001). Cox’s model adjusted for center effects and the presence of diabetes estimated risk ratios of 2.8 for AR40E (p < 0.0005) and 5.1 for XL-Stabi (p < 0.0001), compared to the reference lens SA60AT.

Evaluation of the rate of laser Nd-Yag capsulotomies and data extrapolation

The survival curves resulting from the retrospective study provided a rate of capsulotomy during 4 years of follow-up. After this 4-year follow-up period, two extrapolation methods were used to evaluate the frequency of Yag:

-

Linear extrapolation of the survival curves from 5 years to 26 years of follow-up (that is, until the age of 100 years; patients had a mean age of 74 years at the time of surgical intervention in the retrospective study). The rate of Yag was calculated according to the following method:

For the first 4 years of follow-up: Rate of Yag at y years of follow-up = cumulative rate of Yag at y years – cumulative rate of Yag at (y−1) years.

For the years 5 to 26 of follow-up: Rate of Yag at y years of follow-up = rate of Yag at (y−1) years/2.

It was necessary to divide the rate of Yag by two to fit with long term cohort follow-up curves.11

-

Extrapolation of the survival curves from 5 to 6 years of follow-up, with a constant rate of laser Nd-Yag from then on. Indeed, Billotte et al11 demonstrated that beyond 6 years of follow-up, the cumulative rate of capsulotomies remains constant. The rate of Yag was calculated according to the following method:

For the first 4 years of follow-up: Rate of Yag at y years of follow-up = cumulative rate of Yag at y years – cumulative rate of Yag at (y−1) years.

For the years 5 to 6 of follow-up: Rate of Yag at y years of follow-up = rate of Yag at (y−1) years/2.

Finally, a rate of capsulotomy taking into account survival was calculated to obtain the rate of Yag in the population included at each instant t. This rate was then used in the estimation of costs.

Survival rates were obtained from the INSEE data of January 1st 2005 (http://www.insee.fr).

Consumption of care

Only health care consumption associated with Nd-Yag laser and its complications was estimated, since the cost of cataract surgery itself was similar for the three lenses. It was estimated by the centers that participated in the retrospective European study, for each type of complication identified in a review of the literature.17

Direct unit costs

Cost were expressed in Euro, 2006 (€1 = US$1.35). Two discount rates were used: 0% and 5%.

The costs of treatment and their level of reimbursement were obtained directly from the Dictionnaire Vidal 2006.13 The costs were reimbursed at 65% by the Sickness Fund.

The costs of medical examination and consultations were obtained from the Classification Commune des Actes Médicaux (CCAM) and the Nomenclature Générale des Actes Professionnels (NGAP) 2005 (http://www.insee.fr). These were reimbursed at 70% by the Sickness Fund, with an inclusive fee of €1 for the patient for consultations.

The costs of hospitalization were obtained the “Programme Médicalisé des Systèmes d’Information” (PMSI) (http://www.insee.fr). The most relevant Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) was chosen using the diagnostic classification of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

Indirect unit costs

The low vision and blindness incidence rates following glaucoma or high intraocular hypertension were estimated from the literature. According to Coffey et al14 the prevalence of blindness was 7.3% among glaucoma patients and 14.6% for low vision. Chen et al15 estimated at 15 years that cumulative incidence rate for low vision was 14.6% and 6.4% for blindness. Hattenhauser et al16 found very similar estimates: 27% (low vision) and 9% (blindness), at 20 years. We applied an average yearly incidence rate which was hypothesized to stay constant over the time horizon of our model.

Indirect costs are those costs associated with the development of blindness. They take into account all the socialized costs (converting the accommodation, moving home, help with house work, cooking, etc), the loss of revenue due to visual handicap, the hourly cost of helpers caring for the blind and the social financial help for the handicap. These costs were estimated at €7,242/person/year and €16,679/person/year, for low vision and blindness, respectively, in France.17

Evaluation of costs per complication

The costs for transient complications were estimated using the following formula:

Cost/year of follow-up for a given complication = (final rate of Yag) × (% complication) × (cost of complication).

For permanent complications (glaucoma and persistent elevation of IOP), we multiplied the annual cost per life expectancy taking into account patient gender:

Cost/year of life of follow-up for a given complication = (rate of Yag) × (% complication) × (annual cost of complication) × (life expectancy in years).

A model of budget impact for the Sickness Fund was also designed to calculate costs using the hypothesis that all lens implantations were carried out with one of the three lenses.

Results

Rate of laser Nd-Yag

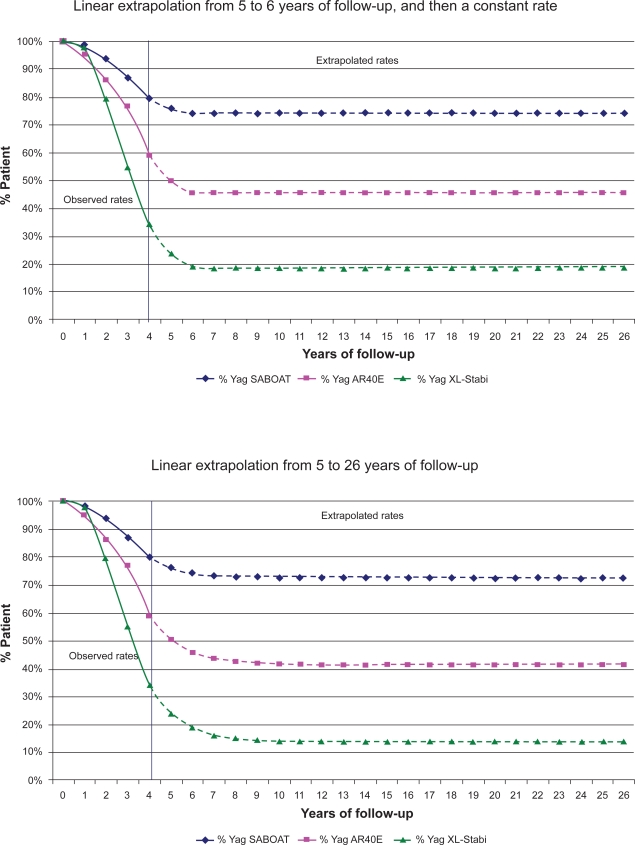

Figure 1 shows the calculated rate of patients not undergoing laser Nd-Yag capsulotomy for each of the three IOL using the two described extrapolation methods. The lowest rate was observed with the hydrophilic acrylic lens, XL-Stabi, with 54.6% of patients not affected at 3 years of follow-up.

Figure 1.

Annual rates of patients not undergoing Nd-Yag per lens according to two levels of extrapolation.

Rate of post-laser Nd-Yag complications and health care consumption

Only the most frequent or most serious complications were considered in this analysis:

Transient increase in IOP: according to published studies, the frequency of IOP increase greater than 10 mmHg after capsulotomy ranges from 4.1% to 6.8%.18–21. For the evaluation of costs, an average rate of 5% was used. In 1% of cases this increase is persistent.22

The appearance of glaucoma: the incidence varies from 0.2% to 6.7% according to different studies, with a median of 1.34%.20,21,23,24 The rate considered in this study was 1.34%. A rate of 7.3% was used to estimate the indirect costs linked to the possibility of becoming blind following glaucoma.14

CMO: the incidence of CMO varies from 0.55% to 4.9% according to different studies, with a median of 1.2%.20,24,25,29–33 The rate considered in this study was 1.2%.

Detachment of the retina: the incidence varies from 0.08% to 4.16% according to different studies10,23,26–40 with a median of 1.2%. The rate considered here was 1.2%.

Decrease in visual acuity: the incidence varies from 1.4% to 7%, with a median of 4%.19,20 The rate considered in this study was 4%.

Formation of Elschnig pearls: approximately 47.6% of patients are affected.6 A second capsulotomy is necessary to remove these pearls in 18% to 33% of cases,6,7 with a mean of 25% of cases.

Table 1 shows the health care consumption for each of these complications. These data were obtained by questioning the centers that participated in the retrospective European study.

Table 1.

Medical consumption according to the type of side effects

| Post-laser Nd-Yag side effects | % of patients affected | Consultations (n) | Treatments | Examinations | Hospitalizations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transient increase in IOP | 5.00% | 2 | Timolol + xalatan, azopt (50%) | Visual field + gonoscopy (50%) | – |

| Glaucoma and persistent elevation of IOP | Glaucoma: 1.34% IOP: 1.00% | 2.5 | Timolol + xalatan or azopt (50%) + betoptic | Visual field + gonoscopy (50%) | Trabeculotomy in 24.2% of cases. CCAM |

| Cystoid macular edema | 1.20% | 3.5 | Indocollyre + timolol or azopt (50%) | Angiography (50%) | – |

| Detachment of the retina | 1.20% | 1 | – | – | 02C02V/02C02W detachment of the retina |

| Decrease in visual acuity | 4.00% | 3 | Angiography | ||

| Elschnig pearls | 47.60% | 1 | Indocollyre + laser Nd-Yag in 25% of cases |

Abbreviations: CCAM, Classification Commune des Actes Médicaux; IOP, intraocular pressure; Nd-Yag, neodymium-Yag.

Total cost of complications

The cost of cataract surgery was the same for all three lenses and was not taken into account in the analysis. In France, the IOL cost is included in the DRG price corresponding to the intervention.

A cost per episode was estimated for the transient complications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unit costs of laser Nd-Yag and its complications

| Post-laser Yag complications | Cost in the 1st year (€) | Annual cost in the following years (€) |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Nd-Yag | 98.16 | 0 |

| Transient increase in intraocular pressure | 62.16 | 0 |

| Persistent increase in intraocular pressure | 277.30 | 277.30 |

| Glaucoma (direct costs) | 277.30 | 277.30 |

| Cost of low vision | 7,242 | 7,242 |

| Cost of blindness | 15,679 | 15,679 |

| Macular edema | 108.13 | 0 |

| Detachment of the retina | 3023.54 | 0 |

| Decrease in visual acuity | 96.32 | 0 |

| Elschnig pearls | 36.31 | 0 |

Abbreviation: Nd-Yag, neodymium-Yag.

For the persistent complications, an annual cost was calculated and applied for each year of survival of the patient.

Cost of complications according to type of IOL

According to the method of extrapolation used, the highest costs were observed for the hydrophilic acrylic lens, XL-Stabi, with a cost per patient of €318.74 to €330.71 (Table 3). Out of the two hydrophobic acrylic lenses, SA60AT was associated with the lowest costs of €99.83 to €104.17 depending on the extrapolation method compared to €208.15 to €218.38 for AR40E. A 5% discount rate did not modify the results dramatically.

Table 3.

Lifetime cost of post-capsulotomy complications per patient and according to type of lens, according to the method of extrapolation used (€)

| SA60AT | AR40E | XL-Stabi | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear extrapolation of the rate of Yag at 5 and 6 years follow-up, and then a constant rate | |||

| Laser Nd-Yag | 21.29 | 44.92 | 67.46 |

| Transient increase in IOP | 0.67 | 1.42 | 2.14 |

| Persistent increase in IOP | 6.35 | 13.24 | 20.26 |

| Persistent increase in IOP leading to blindness (indirect costs) | 18.09 | 37.35 | 58.13 |

| Glaucoma (direct costs) | 8.51 | 17.74 | 27.15 |

| Glaucoma leading to blindness (indirect costs) | 24.24 | 50.05 | 77.90 |

| Macular edema | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.89 |

| Detachment of the retina | 7.83 | 16.52 | 24.80 |

| Decrease in visual acuity | 8.82 | 18.40 | 28.15 |

| Elschnig pearls | 3.75 | 7.91 | 11.88 |

| Direct costs | 57.49 | 120.74 | 182.71 |

| Indirect costs | 42.34 | 87.40 | 136.03 |

| Total | 99.83 | 208.15 | 318.74 |

| Total discounted at 5% | 81.41 | 170.37 | 259.63 |

| Linear extrapolation of the rate of Yag from 5 to 26 years of follow-up | |||

| Laser Nd-Yag | 22.48 | 47.85 | 70.84 |

| Transient increase in IOP | 0.71 | 1.51 | 2.24 |

| Persistent increase in IOP | 6.61 | 13.89 | 21.01 |

| Persistent increase in IOP leading to blindness (indirect costs) | 18.68 | 38.67 | 59.69 |

| Glaucoma (direct costs) | 8.86 | 18.61 | 28.16 |

| Glaucoma leading to blindness (indirect costs) | 25.03 | 51.82 | 79.99 |

| Macular edema | 0.30 | 0.63 | 0.94 |

| Detachment of the retina | 8.31 | 17.69 | 26.18 |

| Decrease in visual acuity | 9.19 | 19.29 | 29.19 |

| Elschnig pearls | 3.96 | 8.42 | 12.47 |

| Direct costs | 60.46 | 127.89 | 191.03 |

| Indirect costs | 43.71 | 90.49 | 139.68 |

| Total | 104.17 | 218.38 | 330.71 |

| Total discounted at 5% | 84.78 | 178.31 | 268.90 |

| Cost at 5 years | |||

| Direct costs | 30.79 | 62.52 | 100.17 |

| Indirect costs | 0.97 | 2.21 | 3.08 |

| Total | 31.76 | 64.73 | 103.25 |

Abbreviation: Nd-Yag, neodymium-Yag; IOP, intraocular pressure.

Irrespective of the extrapolation method or type of lens, the cost of laser Nd-Yag represents approximately 24% of the total cost of cataract surgery complications. The indirect costs linked to glaucoma and persistent elevation of IOP leading to blindness are also an important part of the total cost as they represent approximately 1/3 of the cost overall.

Budget impact model according to type of lens

According to the PMSI data for 2005, 529,987 interventions for cataracts were carried out. The three types of lens studied here represented 64% of the market: 38% for SA60AT, 12% for AR40E and 14% for XL-Stabi. This therefore represents:

204,045 interventions with SA60AT

63,598 interventions with AR40E

74,198 interventions with XL-Stabi, or a total of 341,842 interventions.

Assuming that all of these 341,842 interventions were carried out with the same IOL, we can estimate that the hydrophilic IOL, XL-Stabi, generated an additional cost of €67.5 to €70.2 million (depending on the extrapolation method used) as compared to SA60AT (Table 4). Considering the AR40E hydrophobic lens, the induced incremental cost as compared to SA60AT is lower than that of XL-Stabi. Nevertheless, this additional cost adds up to between €33.9 and €35.9 million which has to be borne by Social Insurance.

Discussion

This economic study is principally based on the results obtained from a retrospective study whose principal objective was to estimate the rate of complications after cataract surgery with the insertion of three different IOL with square edges. The main complication was PCO and its treatment by laser Nd-Yag. This study showed that the lowest rate of capsulotomy was obtained with hydrophobic acrylic lenses and the highest rate with hydrophilic acrylic lenses. As the three lenses studied all had square edges, these results also illustrate the influence of material on the occurrence of Nd-Yag treatment independently of the geometric form of the edges of the lens.41–43

In a previous European study, we showed that the highest cost:efficacy ratio was observed with hydrophilic lenses and the lowest with hydrophobic lenses, in France, Germany, Spain and Italy.44 However, the lenses considered in this European study had very variable geometries. It is therefore difficult to know if the differences in cost estimated were due to material and/or the geometry of the lens.

The lenses studied here all had square edges, a geometry which is considered to be optimal, and the results demonstrate that material nevertheless plays an important role in the rate of capsulotomy and therefore on the cost of cataract surgery. The rate of PCO was highest with hydrophilic acrylic lenses, and the highest costs were also observed with the same lenses.

Generalization to other European countries should be performed cautiously since economic regulation might differ. However all countries having the following characteristics are likely to reproduce the reported results: (1) cost of IOL included in the DRG, (2) a fee-for-service payment for capsulotomy, (3) similar resource utilization and unit costs to treat capsulotomy adverse events.

The association between capsulotomy and retinal detachment was questioned by Neuhann et al45 in a paper published after this model was developed. While no association was reported, it is important to note that cost related to retinal detachment represented less than 8% of the SA60AT undiscounted total cost.

This study is limited by the following:

It is based on a non-randomized retrospective study of efficacy and not on a prospective clinical trial. This fact may cause some potential bias but both designs, of course, have limitations that need to be remembered as the results are considered.

Our work also does not involve standard criteria for assessing PCO. We are assuming surgeons evaluate clinically significant PCO in need of Nd-Yag intervention with reasonable consistency.

Estimates of the cost of complications are based on the one hand on a review of literature reports of the rate of complications, and on the other on a declaration by clinicians of health care consumption associated with these complications. Considering the variability of data in the literature, we have mainly chosen studies in the literature involving large numbers of cases. Our estimates of the economic value of complications are based primarily on the literature or available national data. Thus, while every effort was made to maximize accuracy, there may be some imprecision in our estimates.

Also, we were not able to collect Nd-Yag complication data from patient charts and we had to rely on a model. In France, most of the ophthalmologists are not surgeons and the information is often shared by different practitioners, some of whom did not participate to this survey. More importantly, the incidence rate of Nd-Yag adverse events is fortunately low and the sample size of our survey would not have allowed getting precise estimates. This justifies the use of a model.

Following the literature review, we hypothesized that the Nd-Yag laser adverse events occurred within one year following the capsulotomy. We also hypothesized that, as reported in the literature, the listed (Table 1) adverse events were associated with the use of Nd-Yag laser, ie, they occurred on the top of what would have occurred in patients without Nd-Yag laser. This approach is acceptable when the incidence rate of the adverse event is much higher than the one observed in the general population. For example, the probability of having glaucoma after Nd-Yag laser (5%, Table 1) is x10 that measured in the general population (0.5%).46 Lastly, discounting gives more importance to early (Nd-Yag related events) events than late events (non Nd-Yag related events), minimizing the economic consequences of our hypotheses.

Cost of blindness was limited to indirect costs and did not include medical costs. Also, visual impairments due to macular edema and retinal detachment were not taken into account. Consequently, blindness-related costs were slightly underestimated both on a national health service and societal perspective.

Our results demonstrate that the costs of PCO are not limited to the cost of carrying out Nd-Yag laser but also include the cost of complications, some of which may be persistent. Indirect costs associated with the risk of blindness because of Yag complications represented about 21% of the total costs. Our study showed that it is possible to save money by using more effective strategies.

Table 4.

Budget impact on the Social Security of post-capsulotomy complications for all cataract interventions, per type of lens, according to the method of extrapolation (€)

| SA60AT | AR40E | XL-Stabi | Total difference* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current market share | 204,045 | 63,598 | 74,198 | 341,842 |

| With linear adjustment of the rate of Yag at 5 and 6 years follow-up, then a constant rate | ||||

| Costs with current market share | 18,459,158 | 12,053,962 | 21,365, 979 | 51,879,100 Reference |

| Hypothesis 1: All interventions with SA60AT | 30,925,117 | 30,925,117−20,953,983 | ||

| Hypothesis 2: All interventions with AR40E | 64,790,569 | 64,790,569 12,911,469 | ||

| Hypothesis 3: All interventions with XL-Stabi | 98, 436, 469 | 98,436,469 46,557,369 | ||

| With linear adjustment from 5 to 26 years of follow-up | ||||

| Costs with current market share | 19,337,675 | 12,721,852 | 22,274,013 | 54,333,540 Reference |

| Hypothesis 1: All interventions with SA60AT | 32,396,919 | 32,396,919−21,936,621 | ||

| Hypothesis 2: All interventions with AR40E | 68,380,507 | 68,380,507 14,046,967 | ||

| Hypothesis 3: All interventions with XL-Stabi | 102,619,925 | 102,619,925 48,826,385 | ||

Difference: (Hypothesis i) – (Costs with current market share). A negative figure is associated with saving.

Disclosures and acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Alcon Laboratories Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, England and conducted by Cemka-Eval, Bourg-la-Reine, France. Acrysof® is an Alcon trademark. Andrew Smith and Dr Gilles Berdeaux were Alcon employees. Dr Boureau has participated in national health service trials sponsored by Alcon.

Footnotes

The results of this study were first presented at the 9th annual congress of ISPOR, 29–31th October 2006, Copenhagen, Denmark

References

- 1.Spalton DJ. Posterior capsular opacification after cataract surgery. Eye. 1999;13:489–492. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baratz K, Cook B, Hodge D. Probability of Nd:YAG laser capsulotomy after cataract surgery in Olmsted county, Minnesota. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00795-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ANAES. Evaluation du traitement chirurgical de la cataracte de l’adulte. Février 2000, Paris.

- 4.Altamirano D, Guex-Crosier Y, Bovey E. Complications of posterior capsulotomy with the Nd : YAG laser. Study of 226 cases. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1994;204(5):286–287. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1035537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shani L, David R, Tessler Z, Rosen S, Schneck M, Yassur Y. Intraocular pressure after neodymium: YAG laser treatments in the anterior segment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1994;20(4):455–458. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato K, Kurosaka D, Bissen-Miyajima H, Negishi K, Hara E, Nagamoto T. Elschnig pearl formation along the posterior capsulotomy margin after neodymium: YAG capsulotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23:1556–1560. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(97)80029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurosaka D, Kato K, Kurosaka H, Yoshino M, Nakamura K, Negishi K. Elschnig pearl formation along the neodymium: YAG laser posterior capsulotomy margin. Long-term follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:1809–1813. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rollin JP, Bonnet Y, Etienne E. Notre expérience du laser Yag dans le traitement des cataractes secondaires. Bull Soc Ophtalmol Fr. 1990;(XC):6–7. 579–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boschi MC, Moroni F. Cystoid macular edema following Nd: Yag laser posterior capsulotomy. New Trends Ophthalmol. 1994;9(1):55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javitt JC, Tielsch JM, Canner JK, Kolb MM, Sommer A, Steinberg EP. National outcomes of cataract extraction. Increased risk of retinal complications associated with Nd: YAG laser capsulotomy. Ophthalmol. 1992;99:1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31775-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billote C, Berdeaux G. Adverse clinical consequences of neodymium: YAG laser treatment of posterior capsule opacification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(10):2064–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boureau C, Lafuma A, Jeanbat V, Thoisy K, Berdeaux G, Smith AF.Incidence of laser Nd: YAG capsulotomies after cataract surgery: comparison of three square-edged lenses Can J OphthalmolIn press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dictionnaire VIDAL 2006, VIDAL ed. Paris.

- 14.Coffey M, Reidy A, Wormald R, Xian WX, Wright L, Courtney P. Prevalence of glaucoma in the west of Ireland. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:17–21. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen PP. Risk and risk factors for blindness from glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15(2):107–111. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hattenhauer MG, Johnson DH, Ing HH, Herman DC, Hodge DO, Yawn BP, Butterfield LC, Gray DT. The probability of blindness from open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(11):2099–2104. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lafuma A, Brezin A, Fagnani F, Mimaud V, Mesbah M, Berdeaux G. Nonmedical economic consequences attributable to visual impairment: a nation-wide approach in France. Eur J Health Econ. 2006;7(3):158–64. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shani L, David R, Tessler Z, Rosen R, Schneck M, Yassur Y. Intraocular pressure after neodymium: Yag laser treatments in the anterior segment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1994;20:455–458. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skolnick KA, Perlman JI, Long DM, Kernan JM. Neodumium: Yag laser posterior capsulotomies performed by residents at a veterans administration hospital. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26(4):597–601. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)00467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bath PE, Fankhauser F. Long term results of Nd: Yag laser posterior capsulotomy with the Swiss laser. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1986;12:150–153. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(86)80031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fourman S, Apisson J. Late-onset elevation in intra-ocular pressure after neomydium-Yag posterior capsulotomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:511–513. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080040079031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milazzo S.Le traitement de la cataracte secondaire. Bulletin des Sociétés d’Ophtalmologie de France; Rapport Annuel Novembre 2006. 61–67.

- 23.Stark WJ, Worthen D, Holladay JT, Murray G. Neodymium: Yag lasers: an FDA report. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinert RF, Puliafito CA, Kumar SR, Dudak SD, Patel S. Cystoid edema, retinal detachment and glaucoma after Nd: Yag laser posterior capsulotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambless WS. Neodymium: Yag laser posterior capsulotomy results and complications. J Am Intraocul Implant Soc. 1985;11:31–32. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2776(85)80111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glacet-Bernard A, Brahim R, Mokhtari O, Quentel G, Coscas G. Retinal detachment following posterior capsulotomy using Nd-Yag laser. Retrospective study of 144 capsulotomies. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1993;16(2):87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ambler JC, Constable IJ. Retinal detachment following Nd: Yag capsulotomy. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1988;16:337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1988.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aron-rosa D, Aron J, Cohn H. Use of a pulsed picosecond Nd: Yag laser in 6664 patients. Am Intraocular Implant Soc J. 1984;10:35–39. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2776(84)80074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson S, Kratz R, Olson P. Clinical experience with the Nd:Yag laser. Am Intraocular Implant Soc. 1984;10:52–460. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2776(84)80046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keates R, Steinert R, Puliafito C, Maxwell S. Long term follow-up of Nd:Yag laser posterior capsulotomy. Am Intraocular Implant Soc. 1984;10:164–168. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2776(84)80101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liesegang TJ, Bourne WM, Ilstrup DM. Secondary surgical and Neodymium-Yag laser discussion. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;92:209–212. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winslow RL, Taylor BC. Retinal complications following YAG laser capsulotomy. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:785–789. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33971-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah GR, Gills JP, Durham DG, Ausmus WH. Three thousand YAG laser in posterior capsulotomies. An analysis of complications and comparison to polishing and surgical discission. Ophth Surg. 1986;17:473–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vester CAGM, Bienfait MF, De Jong PTVM, Pameijer JH. Retinal detachment following neodymium:Yag laser capsulotomy. Fortschr Ophthalmol. 1986;83:441–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ficker LA, Vickers S, Capron MRC, Mellerio J, Cooling RS. Retinal detachment following Nd:Yag posterior capsulotomy. Eye. 1987;1:86–89. doi: 10.1038/eye.1987.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dardenne MU, Gerten GJ, Kokkas K, Kermani O. Retrospective study of retinal detachment following neodymium:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1989;15:676–680. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(89)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knoll GE. Knife versus neodymium:Yag laser posterior capsulotomy: a one year follow-up. Am Intraocular Implant Soc J. 1985;11:448–455. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2776(85)80081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider G. Zur Nachstardiszission mit dem Nd:Yag laser. Klin Monastbl Augenheilkd. 1985;187:221–223. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1051024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powel SK, Olson RJ. Incidence of retinal detachment after cataract surgery and neodymium:Yag laser capsulotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1995;21:132–135. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80499-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rickman-Barger L, Florine CW, larson RS, Lindstrom RL. Retinal detachment after neodymium:Yag laser posterior capsulotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90500-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sacu S, Menapace R, Findl O, Kiss B, Buehl W, Georgopoulos M. Long-term efficacy of adding a sharp posterior optic edge to a three-piece silicone intraocular lens on capsule opacification: five-year results of a randomized study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buehl W, Menapace R, Sacu S, Kriechbaum K, Koeppl C, Wirtisch M, et al. Effect of a silicone intraocular lens with a sharp posterior optic edge on posterior capsule opacification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1661–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruger AJ, Schauersberger J, Abela C, Schild G, Amon M. Two year results: sharp versus rounded optic edges on silicone lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:566–570. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith AF, Lafuma A, Berdeaux G, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of PMMA, silicone, or acrylic intra-ocular lenses in cataract surgery in four European countries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2005;12(5):343–351. doi: 10.1080/09286580500180598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neuhann IM, Neuhann TF, Heimann H, Schmickler S, Gerl RH, Foerster MH. Retinal detachment after phacoemulsification in high myopia: analysis of 2356 cases. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008 Oct;34(10):1644–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leske MC, Wu SY, Honkanen R, Nemesure B, Schachat A, Hyman L, Hennis A, Barbados Eye Studies Group Nine-year incidence of open-angle glaucoma in the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(6):1058–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]