Abstract

The dendrites of a number of neuron types function as presynaptic structures, releasing transmitter after action potentials and dendritic spikes. In this regard, dendrites can function like axons, producing discrete outputs after suprathreshold electrical events. However, as the major site of synaptic inputs, dendrites experience ongoing subthreshold fluctuations in membrane potential, raising the question of whether these subthreshold changes can cause changes in transmitter release. Here, we show that mitral cells of the accessory olfactory bulb release glutamate from their dendrites in response to both subthreshold and suprathreshold stimuli. Whereas subthreshold output was typically low under control conditions, it could be enhanced several fold by pharmacological or endogenous activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. These results indicate that presynaptic dendrites can support two distinct forms of output, and can dynamically regulate how electrical activity is coupled to transmitter release.

Introduction

Neurotransmitter release typically occurs only when regenerative action potentials invade axonal branches. Indeed, subthreshold synaptic inputs are strongly attenuated in axons, and are believed to play only a modulatory role in controlling neuronal output (Alle and Geiger, 2006; Shu et al., 2006). However, the basic rules of excitation-secretion coupling may be considerably different for dendrites that are competent for neurotransmitter release, because of the close proximity between sites of input and output, and the diversity of electrical events observed in dendrites. Excitable dendrites support a wide range of electrical signals that vary considerably in their amplitude, spatial extent, and time course (Häusser and Mel, 2003). Thus, both subthreshold electrical activity and subsequent calcium influx may be important triggers of transmitter release in dendrites. Such a diversity of signals would allow a single cell to produce qualitatively different outputs that may serve distinct circuit functions in particular contexts. For example, subthreshold release from dendrites would allow a sensitive local “readout” of membrane potential for small synaptic inputs, whereas suprathreshold release would occur only for appropriately large or coordinated inputs that evoke regenerative responses.

In the present work we studied the glutamatergic output of dendrites of accessory olfactory bulb (AOB) mitral cells, specifically investigating whether these dendrites support both subthreshold and suprathreshold release. The AOB is an excellent model system for studying properties of dendritic release since the majority of its cell to cell coupling is via dendrodendritic synapses (see schematic in supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), and specific alterations of dendritic output in this structure are believed to have behavioral consequences (Kaba et al., 1994). We were particularly interested in exploring the possibility of subthreshold release from mitral cells, given our earlier work on how dendritic excitability facilitates the independent integration of synaptic inputs across mitral cell dendritic tufts (Urban and Castro, 2005). These earlier studies pointed to a possible model of pheromone/odor processing in which each dendritic tuft communicates with local interneuron populations via “tuft spikes”—local regenerative events that occur independently of somatic spiking. Sustained subthreshold output from these same neurons could allow for local synaptic communication even when sensory input is weak, possibly extending the dynamic range of pheromone and odor processing.

Here, we demonstrate that both subthreshold and suprathreshold activity in mitral cell dendrites are coupled to dendritic glutamate release, and that both are sufficient to cause firing in postsynaptic interneurons. Moreover, subthreshold dendritic output was graded and persistent, with larger depolarizations evoking higher rates of self-excitation and feedback inhibition that were sustained for seconds. The rate of subthreshold release was typically low under control conditions, but could be enhanced several-fold after either exogenous or endogenous activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). This suggests that not only is there “dual-mode” dendritic transmitter output from mitral cells, but that these neurons can readily alter the relative efficacies of these output modes. We propose that supporting both subthreshold and suprathreshold transmitter release extends the signaling capabilities of single neurons, allowing them to function as versatile computational elements in local microcircuits.

Materials and Methods

Slice preparation.

Methods are as described previously (Urban and Castro, 2005). Briefly, parasaggital olfactory bulb slices (300–350 μm thick) were prepared from young mice [postnatal day (P) 14–28]. At these ages, the olfactory bulb is fully developed, with mitral cell dendritic morphology at P7 being indistinguishable from adult. Mice were anesthetized (0.1% ketamine/0.1% xylaxine; ∼3 mg/kg, i.p.) and decapitated. Olfactory bulbs were sectioned on a Vibratome while submerged in ice-cold oxygenated ACSF solution containing the following (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1MgCl2, 25 glucose, 2 CaCl2. In some experiments, 0.5 mm ascorbate, 1 mm pyruvate, and 2 mm myo-inositol were added to the slicing medium. For imaging of population calcium responses, slices were incubated in a wellplate chamber for 90 min at 37°C in a solution containing 500 μl of the ACSF solution described above, with 3 μl of 0.01% Pluronic (Invitrogen), and 10 μm Fura2 acetoxymethyl (AM) ester (Invitrogen) in 100% DMSO solution. Humidified carbogen (95% O2/5% CO2) was passed above the surface of the liquid in the chamber to keep the solution oxygenated. All animal care was performed in accordance with the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Carnegie Mellon University.

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell voltage recordings were obtained from the somata of identified AOB mitral cells. Slices were superfused with oxygenated ACSF solution containing the following (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1MgCl2, 25 glucose, 2.5 CaCl2, warmed to 34−36°C. In experiments in which recurrent excitation was studied, 0–0.2 mm MgCl2 was substituted for 1.0 MgCl2 in the above solution to facilitate activation of NMDA autoreceptors. Whole-cell recordings were established using pipettes (resistances of 2–8 MΩ) filled with a solution containing the following (in mm): 150 potassium gluconate, 2 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 sodium phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, and 0.3 Na3GTP, adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH. In the indicated experiments, 5 mm BAPTA was included in this internal solution. In several experiments, a “high chloride” internal solution was used, in which 152 mm KCl was substituted for potassium gluconate and KCl in the above internal solution. Single-cell calcium imaging was performed on cells recorded with electrodes filled with internal solution to which calcium orange (100–200 μm); Invitrogen) was added. Voltage clamp and current clamp recordings were made with a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices). In experiments in Figure 4, in which we evoked fixed numbers of spikes followed immediately by recordings of subthreshold, voltage-dependent currents, we made use of the ability of the 700B to rapidly switch from current to voltage clamp configurations under control of an external trigger. Data were filtered (4 kHz low pass) and digitized at 10 kHz using an ITC-18 (Instrutech) controlled by custom software written in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics). Fluorescence imaging in single cells (Margrie et al., 2001) was performed using a 16 bit back-illuminated frame transfer camera with 10 MHz digitization and 16 μm/pixel (Cascade 512B Roper Scientific) on an Olympus Optical BX51WI microscope fitted with a 20× numerical aperture 0.95 objective at 20–50 Hz. Calcium Orange, Alexa 594, and Fura2 were visualized using a monochromator for excitation (TILL Photonics) and Chroma (Rockingham, VT) CY3 (Calcium Orange and Alexa), and Fura filter sets (excitation filters removed). In all imaging experiments (both single cell and bulk loading), calcium transients were measured as ΔF/F (Urban and Castro, 2005) along lines of interest.

Figure 4.

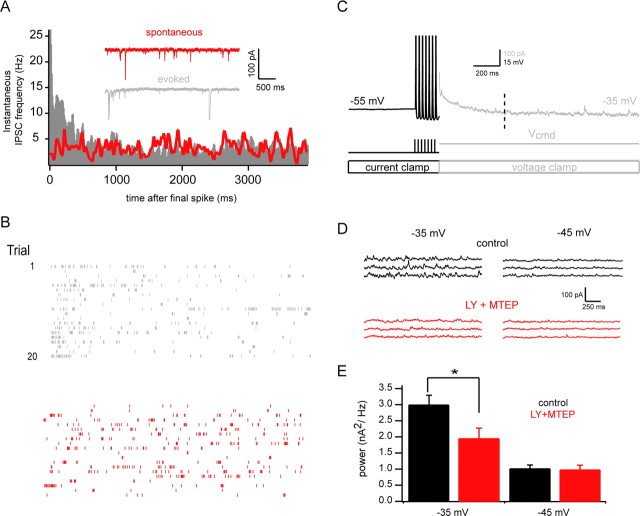

Endogenous glutamate release enhances mGluR-dependent subthreshold release. A, Plot of instantaneous IPSC rates in mitral cells under spontaneous (red) and spike-evoked (gray) conditions (see Materials and Methods). Inset traces show example recordings. For the evoked case, seven spikes at 40 Hz were elicited in current clamped mitral cells, and cells were then rapidly voltage clamped to −80 mV to ensure that observed IPSCs were not caused by release evoked by elevated subthreshold voltage. Recordings were made with KCl-based internal solution to maximize visibility of IPSCs at hyperpolarized potentials. Data are pooled from 10 cells. B, Rasters of IPSC times from a single example cell for 20 evoked trials (gray, top) and 20 spontaneous trials (red, bottom). C, Stimulation protocol for assessing voltage dependence of subthreshold release. Mitral cells were maintained at −55 mV in current clamp and stimulated with brief current pulses (7 × 3 ms at 40 Hz) to evoke the same number of spikes across trials and conditions. Immediately after the last spike, the amplifier was rapidly switched from current clamp to voltage clamp mode to more easily resolve IPSCS and test the subthreshold voltage dependence of IPSC rate. IPSCs observed later than 500 ms after the last spike (indicated by the dashed line) are due exclusively to subthreshold release. D, Example of strong subthreshold voltage dependence of IPSC rate. Traces shown correspond to the gray region of C (detrended for clarity), beginning 500 ms after the last spike (indicated by the vertical dashed line). More IPSCs are observed when the mitral cell is clamped to −35 mV (top left, black) than when it is clamped to −45 mV (top right, black). This subthreshold voltage dependence is eliminated by blockade of group I mGluRs by the antagonists LY367385 and MTEP (bottom, red). E, Summary data for experiments described above (n = 13). Power in the 0–300 Hz band (for detrended, mean-subtracted current traces) for conditions in which cells were voltage clamped to either −35 mV or −45 mV. LY plus MTEP selectively reduces power for the more depolarized condition. (*p < 0.05).

Drugs.

APV, CNQX, and bicuculline were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used at concentrations of 50, 20, and 10 μm, respectively. Gabazine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG), and LY367385 were obtained from Tocris and used at final concentrations of 10, 20, and 100 μm, respectively. 3-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl] pyridine (MTEP) (Calbiochem) was used at 2 μm and prepared from a 25 mm stock in 100% DMSO. LY367585 was prepared in a stock of 100 mm in 100% DMSO. The DHPG stock was prepared in deionized H2O (Milli-Q system) at 100 mm.

Data analysis and statistical tests.

All data are reported as mean ± SEM. Significance was in all cases assessed by nonparametric statistical tests, as indicated. For the experiments in Figure 2, IPSCs were detected using custom written functions in IGOR pro (Wavemetrics), which implemented the event-detecting algorithm described by Kudoh and Taguchi (2002). This analysis resulted in measured rates of spontaneous IPSCs of ∼1 Hz in control conditions (recording at −55 mV), and this rate was reduced to <0.2 Hz by blockade of GABAA receptors. In certain indicated experiments in which we wanted to compare predrug and postdrug levels of synaptic activity, data were analyzed in the frequency domain. Briefly, single-sided power spectra were obtained using automated routines in IGOR pro, which calculate the squared magnitude of the fast Fourier transform. Power was quantified by integrating these spectra within frequency bands of interest. Our reasons for analyzing data in the frequency domain were twofold. First, in experiments in which inhibition was blocked and subthreshold, spike independent recurrent excitation was studied, it was difficult to resolve discrete inward currents that could be detected automatically. This is likely caused by tonic and asynchronous glutamate release, resulting in noisy fluctuations in the current records. Glutamate is also likely to activate predominantly NMDARs, generating relatively slow synaptic currents which are difficult to detect by standard methods. Similar difficulties in the analysis of periods of asynchronous release have been described at other CNS synapses (Neher and Sakaba, 2001). Second, we wanted to be certain that our counts of synaptic events at various holding potentials were independent of driving force. By calculating power spectra of current records, we were able to compute power ratios of predrug and postdrug conditions, ensuring that the normalized measurements compared across voltages did not reflect differences in driving force, but rather underlying rates of synaptic events. For experiments in which spontaneous and spike-evoked rates of IPSCs were compared (Fig. 4; supplemental Fig. S6, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), IPSCs were detected using the above described mini-detection algorithm. IPSC raster plots were then constructed in which the peak-event times were counted as single events. These plots (10–20 trials per cell) were pooled across cells in two groups: one corresponding to spontaneous events, and the other to spike-evoked events. From these pooled raster plots, the instantaneous IPSC rates (10 ms bins) versus time were calculated for the two groups. These plots of IPSC rate versus time were fit using Bayesian Adaptive Regression Splines, which performs spline based generalized nonparametric regression (Behseta et al., 2005; Behseta and Kass, 2005). A likelihood ratio (LR) test was used to compare the two fitted curves pointwise, and significance was assessed for the time dependent quantity −2 log LR, which has a χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom (for details, see Behseta et al., 2007).

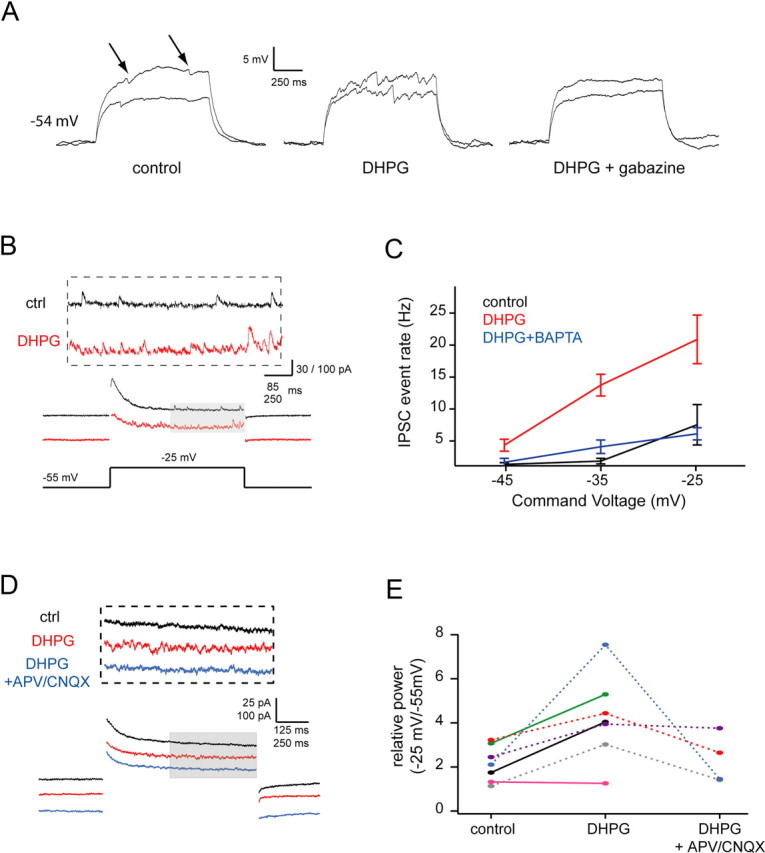

Figure 2.

Activation of group I mGluRs enhances subthreshold glutamate release from mitral cells. A, Traces show IPSPs superimposed on subthreshold depolarizations evoked by current steps of 220 and 290 pA delivered to a mitral cell. Left, Control, arrows indicate putative IPSCs; middle, after 20 μm DHPG; right, after blockade of inhibition with 10 μm gabazine. This cell was maintained at a resting potential of ∼−54 mV for all shown conditions by steady current injection. B, Sample traces showing recurrent IPSCs evoked by a 30 mV voltage step (subthreshold for spiking) under control conditions (black) and after bath application of 20 μm DHPG (red). C, Summary data for experiments similar to B showing IPSC event rate as a function of command voltage (control, DHPG: n = 10; BAPTA internal (5 mm): n = 6). D, Sample traces showing recurrent excitation evoked by voltage steps from −55 mV to −25 mV in control (black), DHPG (red), and DHPG plus APV and CNQX (blue) conditions. All recordings (including control) were made in 10 μm gabazine and 0.2 mm Mg2+ to enhance the detectability of self excitation (a component of which will be NMDAR mediated). E, Group data showing relative power in the 0–110 Hz band (power during Vcmd/power during Vhold) for voltage steps from −55 mV to −25 mV for the same three conditions in D.

Simulation.

A simulation was performed in Igor pro (Wavemetrics) to confirm that changes in IPSC rate could be reliably detected as changes in the power spectra of current records. Briefly, a Poisson process was simulated to construct binary vectors with ones corresponding to IPSC onset times. These vectors were convolved with α functions (τ = 45 ms) to simulate IPSCs. IPSC amplitudes were chosen from a Gaussian distribution with a mean of 1 and SD of 0.2. A 200 s stimulated IPSC record with λ = 20 Hz was chosen as a baseline case, and IPSC records with λ = 2 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz were compared with the 20 Hz record. Power spectra were taken for all records and normalized to the 20 Hz spectrum to observe the approximate frequency band over which differences in IPSC rate were seen.

Results

Subthreshold and suprathreshold activity in mitral cell dendrites evoke glutamate release and activation of postsynaptic interneurons

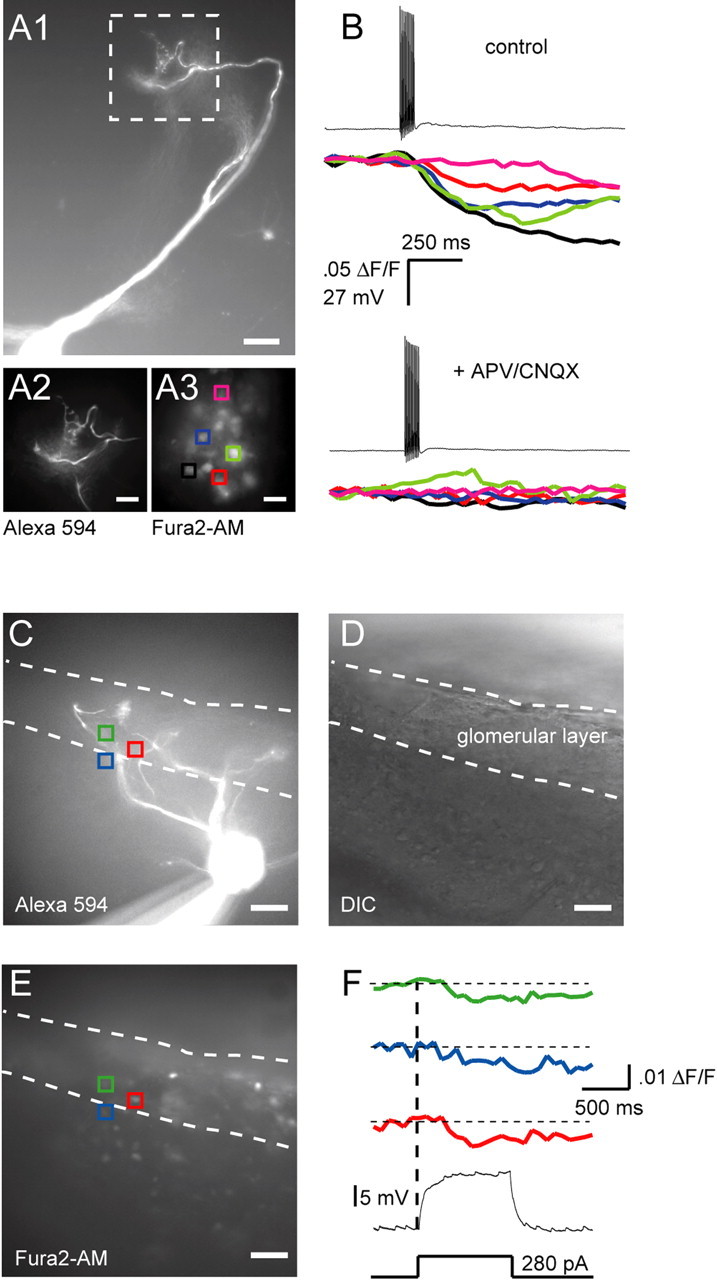

The primary dendrites of mitral cells of the main and accessory olfactory bulb are “axon-like” in that they can initiate and conduct action potentials in a nondecremental manner (Bischofberger and Jonas, 1997; Chen et al., 1997; Ma and Lowe, 2004; Urban and Castro, 2005), and contain neurotransmitter filled vesicles. This suggests that these dendrites may make use of classical, axon-like release mechanisms. To test this, we first examined glutamatergic output from AOB mitral cells evoked by backpropagating action potentials. Action potentials (APs) were elicited by whole-cell current injection (10 pulses × 3 ms at 40 Hz), while calcium transients were monitored in periglomerular (PG) and granule cells that had been loaded with the membrane permeable calcium indicator Fura2-AM. Only PG cells in the vicinity of the tuft of the stimulated mitral cell were activated (Fig. 1A) (4 ± 0.54 PG cells/tuft, average ΔF/F of 4.0 ± 0.5%, n = 5 mitral cells from 5 animals). Similar activation of local PG cells has been observed in the main olfactory bulb after mitral/tufted cell spiking (Murphy et al., 2005). PG cell calcium transients evoked by mitral cell APs were blocked by APV and CNQX, indicating that PG cell activity was caused by glutamate release from mitral cells (Fig. 1B). We believe that this approach demonstrates conclusively that subthreshold activation of a single mitral cell is sufficient to cause calcium influx into PG cell somata.

Figure 1.

Both subthreshold and suprathreshold stimulation of mitral cells activate postsynaptic cells. A1, Image (20×) of an Alexa 594-filled mitral cell. Scale bar, 50 μm. Images beneath the main panel are 3× magnifications of the area demarcated by the white dashed box. A2, Close-up of the mitral cell tuft shown in A1. A3, PG cells bulk loaded with Fura2-AM. Colored squares are regions of interest (ROIs) used to calculate the calcium transients shown on the right. Scale bars: A2, A3, 30 μm. B, Top, PG cell calcium transients evoked by a sequence of 10 backpropagating spikes at 100 Hz. Trace colors correspond to ROI colors in A3. Bottom, Spike-evoked calcium transients from the same PG cells after addition of APV (50 μm) and CNQX (20 μm). C, Fluorescence image (20×) of a mitral cell (different from A1) filled with Alexa 594. Dashed lines demarcate the approximate border of the glomerular layer. Colored squares show the locations of PG cells that responded to subthreshold depolarization of the mitral cell. D, Differential interference contrast image of the same field of view shown in C. E, Cells loaded with Fura2-AM, same field of view as C and D. Colored squares are ROI used to calculate the calcium transients shown to the right. F, PG cell calcium transients elicited by a 1-s-long depolarizing pulse delivered to the mitral cell shown in C. Trace colors correspond to ROI colors in C and E.

Surprisingly, PG cell calcium transients could also be elicited by subthreshold current or voltage steps in mitral cells (Fig. 1C–F; supplemental Fig. S2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), suggesting that mitral cells release glutamate during subthreshold depolarization, and that this release is sufficient to activate some local interneurons (median of 2.5 PG cells activated/mitral cell, average ΔF/F of 0.8 ± 0.2%, n = 4 mitral cells from 3 animals). Thus, subthreshold depolarization for 1 s activated ∼60% as many cells as APs. We next examined whether this activation of interneurons during subthreshold mitral cell depolarization generated recurrent inhibition as is seen after mitral cell spiking. Indeed, we found that subthreshold depolarization of AOB mitral cells in whole-cell current clamp recordings caused IPSP-like membrane potential fluctuations (Fig. 2A) (n = 3). These fluctuations were eliminated after blockade of GABAA receptors by 10 μm gabazine (Fig. 2A), indicating that they were caused by recurrent inhibition evoked by subthreshold activation of the recorded mitral cell (see schematic in supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). To more carefully study these events, mitral cells were voltage clamped at −55 mV and stepped to command potentials between −45 and −25 mV for 1.5 s (Fig. 2B,C). Spontaneous synaptic events were rarely observed at −55 mV (∼1.0 Hz), but elevated IPSC rates were seen at more depolarized command potentials (7.31 ± 3.18 Hz (n = 6) for steps to −25 mV, which was 6.6-fold higher than the rate observed at −55 mV) (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test) (Fig. 2C). IPSCs were observed for the duration of the depolarizing step, and terminated rapidly after repolarization to −55 mV (Fig. 2B).

Subthreshold release of transmitter from mitral cells is enhanced by activation of mGluRs

Previously we had shown a prominent role for group I mGluR activation in regulating recurrent inhibition elicited by spikes in AOB mitral cells (Castro et al., 2007). These effects were mediated in part by alterations in granule cell excitability rather than by direct modulation of mitral cell output. Thus, we next examined the role of these mGluRs in regulating subthreshold release. Consistent with our previous observations, addition of the group I mGluR agonist DHPG (20 μm) caused a large and significant increase in the rate of IPSCs or IPSPs observed in mitral cells (Fig. 2A–C). This increase in IPSC frequency was voltage-dependent, and was partially blocked when 5 mm BAPTA was included in the internal solution (Fig. 2C). Thus, the action of DHPG depended in large part on calcium influx into the mitral cell. IPSCs recorded at hyperpolarized potentials were weakly affected by DHPG, but were enhanced dramatically at depolarized potentials (Fig. 2C), with a 30 mV depolarization from −55 mV eliciting IPSCs at a rate of 20.69 ± 3.80 Hz.

A difficulty in interpreting these apparent increases in IPSC frequency is that the driving force on Cl− (and hence GABAA-mediated IPSCs) is larger at more depolarized potentials. Thus the detectability of IPSCs may increase with depolarization, leading to higher apparent event rates. To assess this possibility, we measured the reversal potential of IPSCs in mitral cells and found that spike-evoked IPSCs reverse at −72.42 ± 2.90 mV (n = 4), and are clearly visible as outward currents (8.6 ± 3.2 pA; n = 5 cells) at −60 mV (supplemental Fig. S3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). This supports the idea that events observed at subthreshold depolarized voltages are evoked, rather than reflecting “unmasked” spontaneous IPSCs.

To more directly measure glutamate release we made use of the fact that glutamate released from mitral cell dendrites “spills over” and binds to NMDA and AMPA receptors located nearby on the same dendrite (Nicoll and Jahr, 1982; Isaacson, 1999; Margrie et al., 2001; Urban and Sakmann, 2002). First, we blocked inhibition with 10 μm gabazine and bathed slices in a 0 Mg2+ ACSF solution to enhance NMDAR-mediated currents. We then depolarized the mitral cell in voltage clamp and recorded spill-over mediated glutamate currents, which were stationary for the duration of voltage steps (supplemental Fig. S5, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Under these conditions depolarization will decrease driving force on glutamatergic currents, reducing detectability of events, resulting in an underestimate of the voltage dependence of release (events observed at −25 mV, for example should be ∼45% the amplitude of events observed at −55 mV, assuming a reversal potential of 0 mV). In these experiments, noisy barrages of inward synaptic currents were evoked by subthreshold depolarization from −55 mV to command potentials as low as −45 mV (supplemental Fig. S4, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). These fluctuations were blocked by addition of the glutamate receptor antagonists APV (50 μm), CNQX (20 μm), and MK801 (30 μm), indicating that they were glutamate-evoked synaptic currents. Because discrete events were often difficult to discern in these traces, we quantified self-excitatory currents by calculating the RMS value of membrane current. The magnitude of these glutamatergic currents increased with voltage (supplemental Fig. S4D, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), despite a less favorable driving force at depolarized voltages. Thus, the enhanced rate of recurrent IPSCs we observed during mitral cell depolarization (Fig. 2) is at least partly a result of glutamate output at subthreshold voltages.

We next turned to the enhancement of asynchronous IPSCs by group I mGluR activation that we observed above. This effect may be attributable to enhanced glutamate release from the mitral cell dendrites (as suggested by the fact that it is blocked by intracellular calcium buffering in the mitral cell), but it also may in part reflect mGluR-mediated increased interneuron excitability (Castro et al., 2007). To test these alternative explanations, we again measured self-excitation of mitral cells and observed the effect of DHPG on self-excitatory currents. We examined self-excitation evoked by subthreshold depolarizations of mitral cells after blockade of inhibition by 10 μm gabazine (in 0.2 mm Mg2+ ACSF), allowing us to assess glutamate release directly from the recorded mitral cell. To account for the possibility that DHPG may cause a nonspecific increase in ambient glutamate (for example via glutamate spillover from neighboring mitral cells), we calculated the ratio of EPSC power during depolarization to EPSC power during resting potential. In mitral cells clamped at −55 mV and stepped to depolarized potentials, DHPG caused enhanced rates of EPSCs and glutamate receptor dependent fluctuations in synaptic current at depolarized potentials (Fig. 2D,E). Thus, activation of group I mGluRs enhances subthreshold release of glutamate by AOB mitral cells.

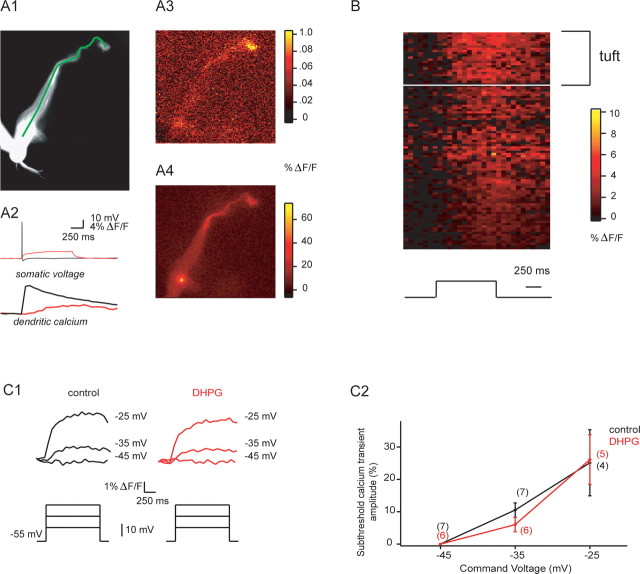

Dendritic calcium influx evoked by subthreshold and suprathreshold dendritic activity

Given the nonlinear relationship between calcium influx and transmitter release described at most synapses (Dodge and Rahamimoff, 1967; Bollmann et al., 2000; Schneggenburger and Neher, 2000), and the observed blockade of subthreshold release by buffering intracellular calcium (Fig. 2C), we reasoned that subthreshold depolarization should cause sustained calcium transients in mitral cell dendrites. We thus first compared dendritic calcium transients evoked by single backpropagating spikes and subthreshold current injection. Both of these stimuli evoked relatively uniform calcium elevations along mitral cell primary dendrites (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, subthreshold calcium transients were visible even in distal tufts in response to subthreshold current injection or voltage clamp depolarizations (Fig. 3A,B). Subthreshold transients evoked by current injection were uniformly smaller than single-AP associated transients (16.2 ± 3.3%; n = 5 cells), and showed slow rising phases (552 ± 88 ms to peak; n = 5 cells). These transients were substantially attenuated by 100 μm Ni2+ (amplitudes after nickel were 28 ± 10% control; n = 5), and in voltage clamp experiments, calcium transients evoked by subthreshold depolarization were enhanced by hyperpolarizing prepulses to −80 mV for 500 ms (calcium transients were 128 ± 11% of control p < 0.01 n = 6 cells). Together, these data indicate that low voltage-activated calcium channels carried the majority of subthreshold calcium current. Somewhat surprisingly, dendritic calcium transients evoked by subthreshold somatic current or voltage steps were unchanged by DHPG (Fig. 3C1,C2). For depolarizations to −25 mV, for example, control transients were 25.1 ± 10.2% the amplitude of single backpropagating action potential (BAP)-evoked transients, whereas transients after DHPG addition were 26.1 ± 7.7% the amplitude of BAP-evoked transients (p = 0.59, Wilcoxon signed rank test, n = 5); peak calcium influx in response to single BAPs was not altered appreciably by DHPG (before: 18.0 ± 1.8% ΔF/F; after: 18.9 ± 1.0% ΔF/F; p = 0.43, Wilcoxon signed rank test, n = 6), allowing us to normalize subthreshold transient amplitudes for comparisons across cells. This general lack of effect of DHPG on subthreshold calcium transients can also be seen directly in the ΔF/F transients shown in Figure 3C1. Similarly, resting calcium levels in mitral cell dendrites were unchanged by DHPG (resting fluorescence after DHPG = 101 ± 2% control values, n = 5 cells, p > 0.5 for control vs DHPG).

Figure 3.

Mitral cell dendritic calcium transients associated with subthreshold depolarization and backpropagating spikes. A1, Fluorescence image of a mitral cell (tuft is toward top right) with line of interest (LOI) shown along the principal dendrite. A2, Somatic voltage and dendritic calcium in response to a single backpropagating spike (black) and a 1-s-long subthreshold current step (red). A3, Peak fluorescence in the principal dendrite after the subthreshold current step shown in A2 (red). Note that calcium influx is observed even in the distal dendrite and tuft. A4, Peak fluorescence in response to the single backpropagating spike shown in A2 (black). B, Mean spatiotemporal map of % ΔF/F in five principal dendrites from five cells during subthreshold current injection. Black trace on the bottom indicates the time course of current injection. C1, Sample sweeps showing dendritic calcium transients during somatic voltage steps from −55 mV to the indicated command potentials (black, control; red, DHPG). C2, Summary data for experiments described in C1. Data for subthreshold transients are normalized to the peak of calcium transients evoked by single backpropagating action potentials recorded in the same cell—as shown in A2 above.

In total, these data suggest that activation of group I mGluRs enhances the coupling between calcium influx and transmitter release without directly altering calcium influx through channels mediating subthreshold release. Consistent with this “priming” effect of mGluRs on transmitter release, we also observed that release is enhanced for suprathreshold stimuli. In experiments in which we recorded spike-evoked recurrent EPSPs (rEPSPs) in mitral cells, DHPG (20 mm) increased rEPSP amplitude from 2.46 ± 1.02 mV to 4.43 ± 0.97 mV; n = 5; p < 0.03 (supplemental Fig. S7, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Endogenous activation of mGluRs is sufficient to enhance subthreshold dendritic transmitter release

We next tested whether the mGluR-dependent enhancement of subthreshold release occurs after physiological release of glutamate. To test this, we evoked action potentials (7 pulses × 3 ms duration at 40 Hz) in mitral cells in current clamp, and rapidly (within a few milliseconds after the last AP) switched to voltage clamp to hold cells at potentials of either −45 or −35 mV in interleaved trials (Fig. 4) (see also Materials and Methods). This allowed us to evoke a specific number of mitral cell APs, which would cause glutamate release and subsequent mGluR activation, and then examine the voltage dependent, subthreshold component of recurrent inhibition in voltage clamp. Since the number of spikes was the same across trials, the rate of action potential evoked recurrent IPSCs should be identical for the two command potentials. Thus, differences in IPSC rate observed at the two potentials will be a function of voltage command potential after the spikes. To ensure that the IPSCs studied were not AP evoked, we only examined IPSCs occurring in a 1 s long interval beginning 500 ms after the final spike [in a related set of experiments, we determined the duration of AP-evoked recurrent inhibition to be <500 ms (Fig. 4A; supplemental Fig. S6, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material)]. Under control conditions, IPSC-associated power was approximately threefold greater at −35 mV than at −45 mV (Fig. 4E), comparable to the fold difference we observe between these two potentials after addition of DHPG (Fig. 2). Addition of the mGluR1 and mGluR5 antagonists LY367385 (100 μm) and MTEP (2 μm) eliminated the difference in IPSC-associate power observed at −35 versus −45 mV (Fig. 4E), demonstrating that mGluR activation by self excitation is sufficient to enhance the subthreshold component of release. The most relevant comparisons are between control and drug conditions within each voltage condition, as these demonstrate that reduction of IPSC power by LY plus MTEP is selective for more depolarized holding potentials (see also supplemental Fig. S8, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Discussion

We have shown that both subthreshold and suprathreshold depolarization cause release from dendrites of AOB mitral cells. Both forms of dendritic release can elicit spiking in postsynaptic interneurons, although suprathreshold release typically activated more cells than subthreshold release. Subthreshold glutamate release and concomitant recurrent inhibition were low under control conditions (IPSCs occurred at ∼7 Hz for depolarizations to −25 mV), but could be enhanced up to sixfold by pharmacological or physiological activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Activation of endogenous receptors by trains of action potentials in single mitral cells resulted in an approximate doubling of subthreshold release. These results indicate that mitral cells support two qualitatively different output modes whose relative efficacy can be changed by activation of neuromodulatory systems.

Functions of subthreshold release

Since the first descriptions of dendrites as presynaptic elements, there has been great interest in understanding the coupling of electrical signals to dendritic transmitter output (Egger and Urban, 2006; Margrie and Urban, 2008). This interest originally derived from the proximity of sites of synaptic input and output, and was enhanced by the observation that dendrites express voltage-dependent channels and exhibit regenerative activity at multiple spatio-temporal scales. Recent work by Acuna-Goycolea et al. (2008) underscores this point by demonstrating that GABA release from thalamic interneurons occurs for both plateau-like dendritic calcium spikes, as well as rapid, full-blown sodium spikes. Interestingly, these distinct regenerative events also evoke GABA release over distinct timescales. Similarly, synapse specificity of cannabinoid release from Purkinje cell dendrites can be tuned by the spatial extent of local dendritic spikes (Rancz and Häusser, 2006).

Here, we show that mitral cell dendrites release transmitter during subthreshold depolarization, in the absence of sodium spikes, or other forms of regenerative activity. This suggests that the olfactory bulb makes use of a “hybrid” neural code in which sensory information is encoded by the rate and/or timing of mitral cell spiking, as well as by the membrane potential of sufficiently activated mitral cells. Thus, bulbar circuit operations such as lateral inhibition and self-excitation/inhibition may occur among mitral cells receiving sensory inputs, but which do not send action potentials out of the bulb. One consequence of this is that local circuits consisting of mitral cells and interneurons that receive only weak sensory inputs could still participate in local computations that would ultimately contribute to the “decision” of mitral cells to spike or not. Since mitral cells receive direct inputs from sensory neurons and send their axons out of the bulb, such local processing may be critical for generating selective output and controlling whether spikes are fired by mitral cells.

In situations in which many glomeruli are activated by a multicomponent odor or pheromone mixture, for example, outputs from mitral cells responding to “trace” quantities of an odorant could modulate the firing of postsynaptic neurons. Subthreshold transmitter release may be especially important in systems like the AOB, where the firing of only a few principal neurons is believed to be behaviorally relevant (Luo et al., 2003). Because spiking is costly in these same systems if it occurs for inappropriate stimuli, regulatory feedback occurring during subthreshold integration may provide a “safety check” on spike generation.

Regulation of neuronal output by subthreshold membrane potential

Several recent studies have shown that subthreshold membrane voltage can influence action potential evoked transmitter release from axons of CNS neurons (Awatramani et al., 2005; Alle and Geiger, 2006; Shu et al., 2006). In some of these cases, subthreshold depolarization causes elevations of calcium that are sufficient to potentiate release. These “priming” effects on release will be especially pronounced in release-competent dendrites, given the close proximity of sites of synaptic input and output: in essence, dendritic release sites are more likely to experience large subthreshold depolarizations (and subsequent elevations of calcium) than their axonal counterparts. Evidently, these elevations of basal calcium concentration can also elicit dendritic release without APs.

This observation builds on related studies describing other “nontraditional” forms of transmitter release that occur in the absence of action potentials or obvious regenerative activity. Chávez et al. (2006) have recently shown that activation of calcium permeable AMPA receptors alone can directly trigger GABA release from A17 amacrine cells. Similarly, calcium influx through NMDA receptors may be sufficient to directly evoke GABA release from olfactory bulb granule cells (Chen et al., 2000).

MGluR modulation of release

One of the striking attributes of the subthreshold release we studied was its enhancement by activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Although presynaptic mGluRs modulate release in many cases by altering calcium currents (Takahashi et al., 1996), we observed no change in the amplitude of depolarization-evoked calcium transients in mitral cell dendrites in the presence of group I mGluR agonists. This suggests that mGluRs have modulatory actions on release machinery downstream of calcium entry. Such effects have been described in several preparations. In CA3 pyramidal cells, for example, the frequency of mEPSCs is reduced by mGluR agonists even when voltage gated calcium channels are blocked (Scanziani et al., 1995). Mechanistically, such “late-step” changes in release may involve alterations in the calcium cooperativity and/or sensitivity of vesicle exocytosis initiated by second messenger cascades. Our data directly address this issue in the AOB, but given the similarity of mGluR effects seen in AOB and main olfactory bulb (MOB) (Castro et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2007), similar facilitation of release may occur in MOB mitral cells as well.

Many studies of such active dendritic integration emphasize the role of regenerative conductances, which can shape the amplitude and time course of synaptic inputs. Although such regenerative activity allows subtle computations to be performed by single neurons, most models of neuronal function presume that neurons are feedforward devices that act in relative isolation while integrating their inputs. In contrast, our discovery of subthreshold dendritic release indicates that single neurons can produce outputs in the absence of spikes, which in turn allows feedback via local circuits to occur during integration.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant RO1 DC005798 (N.N.U.) and a National Research Service Award Predoctoral Fellowship [F31 DC08230 (J.B.C.)]. We thank Greg Larocca for technical assistance.

References

- Acuna-Goycolea C, Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Active dendritic conductances dynamically regulate GABA release from thalamic interneurons. Neuron. 2008;57:420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Geiger JR. Combined analog and action potential coding in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science. 2006;311:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1119055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani GB, Price GD, Trussell LO. Modulation of transmitter release by presynaptic resting potential and background calcium levels. Neuron. 2005;48:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behseta S, Kass RE. Testing equality of two functions using BARS. Stat Med. 2005;24:3523–3534. doi: 10.1002/sim.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behseta S, Kass RE, Moorman DE, Olson CR. Testing equality of several functions: analysis of single-unit firing-rate curves across multiple experimental conditions. Stat Med. 2007;26:3958–3975. doi: 10.1002/sim.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger J, Jonas P. Action potential propagation into the presynaptic dendrites of rat mitral cells. J Physiol. 1997;504:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.359be.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmann JH, Sakmann B, Borst JG. Calcium sensitivity of glutamate release in a calyx-type terminal. Science. 2000;289:953–957. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro JB, Hovis KR, Urban NN. Recurrent dendrodendritic inhibition of accessory olfactory bulb mitral cells requires activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5664–5671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0613-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez AE, Singer JH, Diamond JS. Fast neurotransmitter release triggered by Ca influx through AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Nature. 2006;443:705–708. doi: 10.1038/nature05123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WR, Midtgaard J, Shepherd GM. Forward and backward propagation of dendritic impulses and their synaptic control in mitral cells. Science. 1997;278:463–467. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WR, Xiong W, Shepherd GM. Analysis of relations between NMDA receptors and GABA release at olfactory bulb reciprocal synapses. Neuron. 2000;25:625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge FA, Jr, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action a calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Hayar A, Ennis M. Activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors on main olfactory bulb granule cells and periglomerular cells enhances synaptic inhibition of mitral cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5654–5663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5495-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger V, Urban NN. Dynamic connectivity in the mitral cell-granule cell microcircuit. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häusser M, Mel B. Dendrites: bug or feature? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:372–383. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS. Glutamate spillover mediates excitatory transmission in the rat olfactory bulb. Neuron. 1999;23:377–384. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaba H, Hayashi Y, Higuchi T, Nakanishi S. Induction of an olfactory memory by the activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1994;265:262–264. doi: 10.1126/science.8023145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh SN, Taguchi T. A simple exploratory algorithm for the accurate and fast detection of spontaneous synaptic events. Biosens Bioelectron. 2002;17:773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(02)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Fee MS, Katz LC. Encoding pheromonal signals in the accessory olfactory bulb of behaving mice. Science. 2003;299:1196–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1082133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Lowe G. Action potential backpropagation and multiglomerular signaling in the rat vomeronasal system. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9341–9352. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1782-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margrie TW, Urban NN. Dendritic neurotransmitter release. In: Stuart G, Spruston N, Hausser M, editors. Dendrites. Oxford: Oxford UP; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Margrie TW, Sakmann B, Urban NN. Action potential propagation in mitral cell lateral dendrites is decremental and controls recurrent and lateral inhibition in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:319–324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011523098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GJ, Darcy DP, Isaacson JS. Intraglomerular inhibition: signaling mechanisms of an olfactory microcircuit. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:354–364. doi: 10.1038/nn1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakaba T. Estimating transmitter release rates from postsynaptic current fluctuations. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9638–9654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09638.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA, Jahr CE. Self-excitation of olfactory bulb neurones. Nature. 1982;296:441–444. doi: 10.1038/296441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancz EA, Häusser M. Dendritic calcium spikes are tunable triggers of cannabinoid release and short-term synaptic plasticity in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5428–5437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5284-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission by muscarinic and metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in the hippocampus: are Ca2+ channels involved? Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00119-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature. 2000;406:889–893. doi: 10.1038/35022702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Hasenstaub A, Duque A, Yu Y, McCormick DA. Modulation of intracortical synaptic potentials by presynaptic somatic membrane potential. Nature. 2006;441:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature04720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1996;274:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban NN, Castro JB. Tuft calcium spikes in accessory olfactory bulb mitral cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5024–5028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0297-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban NN, Sakmann B. Reciprocal intraglomerular excitation and intra- and interglomerular lateral inhibition between mouse olfactory bulb mitral cells. J Physiol. 2002;542:355–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]