Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a bioactive phospholipid that impacts migration, proliferation, and survival in diverse cells types, including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and osteoblast-like cells. In this study, we investigated the effects of sustained release of S1P on microvascular remodeling and associated bone defect healing in vivo. The murine dorsal skinfold window chamber model was used to evaluate the structural remodeling response of the microvasculature. Our results demonstrated that 1:400 (w/w) loading and subsequent sustained release of S1P from poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLAGA) significantly enhanced lumenal diameter expansion of arterioles and venules after 3 and 7 days. Incorporation of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) at day 7 revealed significant increases in mural cell proliferation in response to S1P delivery. Additionally, three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds loaded with S1P (1:400) were implanted into critical-size rat calvarial defects and healing of bony defects was assessed by radiograph x-ray, microcomputed tomography (μCT), and histology. Sustained release of S1P significantly increased the formation of new bone after 2 and 6 weeks of healing and histological results suggest increased numbers of blood vessels in the defect site. Taken together, these experiments support the use of S1P delivery for promoting microvessel diameter expansion and improving the healing outcomes of tissue-engineered therapies.

Keywords: tissue engineering, controlled drug release, phospholipids, drug delivery, bone healing, growth factors

Introduction

The development of effective strategies to stimulate and control the growth of microvascular networks is a critically important clinical need with potential for widespread impact on the field of tissue engineering [1–3]. Current strategies have focused primarily on inducing angiogenesis, the sprouting of new capillaries from pre-existing vessels resulting in new capillary networks [4–7]. These strategies are aimed at the generation of new vessel networks to prevent ischemia and to enhance both nutrient and oxygen exchange. Delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), the most well-studied angiogenic growth factor to date, has shown significant promise in promoting neovascularization at early stages of ischemic tissue repair [7–9]. However, concerns persist regarding its efficacy due to observations of poorly organized, leaky, and/or hemorrhagic blood vessel formation [10]. Additionally, nascent vascular networks formed in response to VEGF are often prone to regression if not adequately matured, or stabilized, by mural support cells [11].

The successful formation of mature microvascular networks, with long-term patency that are no longer prone to regression, is largely dependent upon the recruitment of mural support cells (both pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells) to rapidly stabilize newly formed blood vessels [11–13]. This process of mural cell recruitment is a key component of arteriogenesis, the process by which new arterioles form and existing arterioles structurally remodel, thereby increasing the number and diameter of resistance vessels in a tissue [10, 13–15]. Arteriogenesis is thought to occur via a sequential progression involving the proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells and pericytes to the ablumenal surface of new microvessels followed by the differentiation of SMCs and pericytes to a mature, contractile phenotype [13–15]. Proposed approaches for therapeutic induction of arteriogenesis have been aimed at focal delivery of one or more well-established polypeptide growth factors, such as PDGF-BB (platelet-derived growth factor), Ang1 (angiopoiten 1), and TGF- β (transforming growth factor) [13]. Studies have shown that temporal delivery of growth factors, such as VEGF164 and Ang1 [12] or VEGF165 and PDGF-BB [16, 17] can be utilized to successfully stabilize nascent vascular networks in adult tissues. But, while growth factors are powerful and promising tools for developing effective strategies in regenerative medicine, they also possess several potential drawbacks, such as high costs associated with recovery and purification of recombinant proteins and susceptibility to aggregation and degradation [6, 18]. Alternatively, delivery of small molecules as inducers of therapeutic arteriogenesis to prevent vessel regression while promoting network stabilization remains an understudied concept.

Exogenous delivery of sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P), a bioactive phospholipid, has been shown to enhance both proliferation and migration of vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in vitro [19–22]. This response is mediated predominantly via signaling through a family of G protein-coupled receptors, formerly classified as the Edg receptors [23, 24]. S1P is released by hemangioblastic cells, including platelets, mast cells, monocytes, and endothelial cells, in nanomolar concentrations into the bloodstream, but can additionally be secreted in higher concentrations by activated platelets in areas of endothelial injury to aid in wound repair [25]. S1P is thought to be a key signaling molecule, spanning both paradigms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis, [26–28] making it an attractive therapeutic agent. S1P stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and migration [28, 29], suggestive of an angiogenic role, and reduces oxygen and nutrient-deprived cell death [30]. Furthermore, and suggestive of its role in promoting arteriogenesis, S1P possesses significant ability to promote vascular stabilization by recruitment of pericytes and SMCs to newly-formed vessels [31] and to stimulate SMC proliferation [21], migration [31], and differentiation into a more contractile phenotype [22]. Murine knockout studies emphasize S1P as being a necessary arteriogenic factor in vascular development, as global S1P receptor 1 (S1P1) knockouts are embryonic lethal, hemorrhaging as a result of aberrant recruitment of smooth muscle cells to nascent endothelial tubes [32].

Since phospholipid secretion in vivo is associated with degranulating platelets and blood clot formation, S1P is likely to play a role in many tissue repair processes, including bone regeneration. Bone is a highly vascularized tissue that relies on the incorporation of blood vessels to transport osteoprogenitor cells and osteogenic factors, as well as nutrients and oxygen [33]. Recent reports indicate that S1P is a potent osteoblast mitogen in vitro, stimulating proliferation [34] and exerting anti-apoptotic effects in osteoblastic cells [35]. Thus, S1P is a single bioactive factor with multiple cellular targets, including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and osteoblastic cells, making it an attractive molecule for bone repair strategies. We postulate that the delivery of S1P may permit the simultaneous recruitment of osteoprogenitor cells and the development of mature vascular networks, thereby enhancing new bone formation in a model of cranial repair.

Taken together, the data highlight the utility of S1P as both a therapeutic agent to enhance microvascular remodeling and enhance bone regeneration; however, implantation, optimization, and in vivo evaluation of efficacy remain understudied. In the first part of this study, we investigate the potential of S1P to enhance both angiogenesis and arteriogenesis utilizing the murine dorsal skinfold chamber model. This animal model was selected because it enables rigorous assessment of vascular changes, whereby the same vessels can be tracked over time to yield quantitative results of total vessel length or diameter. We hypothesize that sustained delivery of S1P from an FDA-approved biodegradable polymer results in microvascular remodeling in vivo by stimulating neovascularization and vascular diameter enlargement, indicative of its proposed angiogenic and arteriogenic roles, respectively. Measurements of total length density and lumenal expansion of existing microvessels are quantified across a seven-day time-course to chart real time vessel remodeling in response to local S1P delivery. Establishing sustainable vessel networks to provide nutrients and oxygen to the regenerate tissue is central to many tissue engineering problems. Thus, in the second phase of this work, we develop small molecule delivery strategies to concurrently enhance both the formation of functional microvascular networks and new bone tissue over an extended time period. Bone healing is assessed by implanting S1P-loaded microsphere based scaffolds in a critical-size cranial defect model and monitoring defect repair over a 42-day time period by radiograph x-ray, microcomputed tomography (μCT), and histology.

Materials and Methods

Encapsulation of S1P in polymeric thin films

Sphingosine-1 phosphate was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) and resolubilized in methylene chloride to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. 50:50 PLAGA (methyl ester capped, inherent viscosity = 0.77 dL/g, Mw = 72.3 kDa; Lakeshore Biomaterials, Birmingham, AL) was used to solvent cast thin films in a 1:400 (w/w) ratio of S1P:PLAGA dissolved in methylene chloride. The solution was slowly poured into a Teflon mold (area = 8.8 cm2) and stored at −20°C until the solvent evaporated completely. Control films were fabricated exactly as above, omitting the addition of S1P. Both films were lyophilized for 24 hours to extract any remaining solvent (Labconco Corp., Kansas City, MO). Films with a diameter of 1mm and height of 500μm were then extracted using a 1mm biopsy punch (Acuderm, Inc., Ft. Lauderdale, FL).

Evaluation of Release Kinetics and Mathematical Diffusion Model

A mathematical model was created to approximate the concentration of S1P in the tissue space after release from a PLAGA film. We used an unsteady-state mass transport model to describe the diffusion of S1P from the film as a function of radial distance:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where rf is the radius of the PLAGA film, D1 is the diffusivity in the film, D2 is the diffusivity in tissue, and ku is a drug uptake term. Degradation of 50:50 PLAGA was assumed to be negligible in the 7-day time-frame of the dorsal skinfold window chamber studies based on in vitro degradation data showing a significant lag phase up to day 14 [36]. D1 = 7.7 × 10−12 cm2/s was assumed for a drug of similar molecular weight diffusing from PLAGA [37] and D2 = 6.4 × 10−7 cm2/s was assumed for S1P bound to albumin through water [26]. The drug uptake term, ku, was assumed for FTY720, a structural analog of sphingosine, to be 1.3 × 10−4 s−1 based on results from a one-compartment pharmacokinetic model with first-order absorption and elimination [38]. Because of FTY720’s rapid initial absorption and exceptionally long half-life (~7 days), the blood concentration of FTY720 remains relatively stable after administration [39], which may not hold true in the case of S1P due to its insolubility in aqueous solutions in the absence of a carrier protein [40] and much shorter half-life (~2 hours) [41]. Thus, we acknowledge that FTY720 may be more potent than S1P. The initial conditions of the model accounted for the concentration of S1P in the polymer to be 1.82 mg/ml (loading ratio of 1:400, S1P:PLAGA) and no free S1P in the tissue. The model was then solved using mathematical software (MATLAB 7.2, Natick, MA).

Dorsal Skinfold Window Chamber Surgical Procedure

Animal experiments were performed using sterile techniques in accordance with an approved protocol from the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6 mice weighing between 18 and 25 grams were implanted with dorsal skinfold window chambers (APJ Trading Company, Inc., Ventura, CA). Mice were treated with a pre-anesthetic of atropine (0.08 mg/kg IP) and further anesthetized using intraperitoneal (IP) injections of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg). Dorsal skin was shaved, depilated, and sterilized using triplet washes of 70% ethanol and iodide. A double-layered skin fold was elevated off the back of the mouse and pinned down for surgical removal. The titanium frame of the window chamber was surgically fixed to the underside of the skinfold. The epidermis and dermis were removed from the top side of the skinfold in a circular area (diameter = approximately 12mm) to reveal the underlying vasculature. Exposed tissue was kept hydrated with sterile Ringer’s solution (137.9 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.9 mM CaCl2, and 23 mM NaHCO3). The titanium frame was then mounted on the topside of the tissue and attached to its underlying counterpart. The dorsal skin was sutured to the two titanium frames and the exposed tissue was sealed with a protective glass window. Mice were allowed to recover in heated cages and subsequently administered buprenorphine via subcutaneous injection (0.1–0.2 mg/kg) as a post-operative analgesic. All mice received a laboratory diet and water ad libidum throughout the time-course of the experiment.

Implantation of thin films and intravital image acquisition

S1P-loaded or control films were implanted into the window chamber 7 days post-surgical implantation, hereafter referred to as Day 0. Mice were anesthetized via 2% isoflurane mixed with 1 ml/min O2. Subsequently, the glass window was removed to expose the thin layer of vessel networks The window chamber was flooded with 1 mM adenosine in Ringer’s solution (3 × 5 minutes) to maximally dilate all vessels and maintain tissue hydration. Following the last administration of adenosine, the solution was aspirated and two films (either both loaded or both unloaded) were placed equidistant from one another and from each edge of the window. The mouse was then mounted to a microscope stage and imaged non-invasively using a x4 objective on an Axioskop 40 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Images were captured using an Olympus MicroFire color digital camera and PictureFrame image acquisition software (Optronics, Goleta, CA). Individual images were later photomerged into a single image of the entire microvascular network using Adobe Photoshop CS. Mice were initially imaged on Day 0 following film implantation and again on Day 3 and Day 7.

Quantitative Microvascular Metrics

Intravital microscopy montages of entire vascular windows at Day 0, Day 3, and Day 7 were analyzed using a combination of Adobe Photoshop CS and Image J software packages. (Image J can be downloaded from the National Institutes of Health website: http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). First, circles with a diameter of 5mm (or 2mm concentric radius from outer edge of one film) were cropped around each film, with no overlap of the two circles. For microvascular length density measurements, vessels located within these cropped images were traced using Photoshop and skeletonized using Image J. These binary images were analyzed by counting the total number of pixels, representing the total length of all traced vessels. To assess changes in lumenal diameter, arteriole-venule pairs were identified in the 2mm cropped images. Identical vessel segments were labeled on Day 0, Day 3, and Day 7 images at the bisection of each vessel segment in between branch points. Internal diameters based on blood column widths were measured using Image J. Day 0 diameter measurements were used to bin vessels by size at the onset of the experiment to track how initial size affects lumenal expansion potential.

BrdU Incorporation

After the final imaging on Day 7, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 3mg of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (Calbiochem, EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA) in 300μl of PBS and allowed to recover from anesthesia. The mice were left alone for a period of four hours, permitting the BrdU to incorporate into the newly synthesized DNA of replicating cells, after which point they were euthanized for tissue harvest.

Tissue Harvest, Fixation, and Histology

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane mixed with 1 ml/min O2 and euthanized with an overdose of Nembutal administered intraperitoneally. Immediately, the chest cavity was opened and the vasculature was perfused with 10ml of 1x Tris-buffered saline plus 0.1mM CaCl2 and 2% heparin via the right ventricle, followed by 10ml of 1x Tris-buffered saline plus 0.1mM CaCl2 and 10ml 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for vessel fixation. During this time, 4% PFA was dripped onto the exposed vascular region of the window chamber. After perfusion and fixation, the window chamber tissue was excised using surgical microscissors and placed in a histological cassette in 4% PFA. Tissues were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 5μm slices and mounted onto glass slides.

Immunohistochemistry, Image Acquisition and BrdU Quantification

Histological sections mounted on glass slides were de-paraffinized and rehydrated. Briefly, slides were incubated in two 10 minute washes of xylenes to remove the paraffin from the tissue sections. Next, the samples were rehydrated using a graded series of ethanol solutions: two washes for 5 minutes each of 100% ethanol, 95% ethanol, and 70% ethanol followed by two 5 minute washes of deionized water. Rehydrated tissues were then incubated in 0.1N HCl for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by 1N HCl for 30 minutes at 37°C to denature the DNA and expose incorporated BrdU. Samples were washed in phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% saponin and 2% bovine serum albumin (PBS/saponin/BSA) 3 × 10 minutes each. Each tissue section (4 sections/film/mouse) was then immunolabeled for smooth muscle α-actin using CY3-conjugated monoclonal anti-SM α-actin (Sigma) diluted 1:500 in PBS/saponin/BSA and BrdU using anti-Bromodeoxyuridine, clone PRB-1, biotin conjugated antibody (1:100) (Chemicon). TOTO-3 iodide (Invitrogen) was used to label cell nuclei (1:1000). Slides were incubated with antibodies for approximately 15 hours at 4°C. Tissues were subsequently washed 3 times in PBS/saponin for 10 minutes each and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen) was applied to bind the anti-BrdU (1:1000). Samples were washed again, 3 × 10 minutes each, and then mounted using a 50:50 solution of PBS and glycerol.

Immunolabeled histological tissue sections were imaged using a Nikon TE 2000-E2 confocal microscope equipped with a Melles Griot Argon Ion Laser System and Nikon D-Eclipse C1 accessories. Representative images were acquired using a 60×/1.45 NA Nikon oil immersion objective and Nikon EZ-C1 software. To quantify proliferation of mural cells in response to S1P, SMA-positive cells that formed an obvious microvessel with a lumen were first identified in each tissue section. The total number of nuclei (stained with TOTO-3) comprising each microvessel with SMA-positive mural cells was counted and then the percentage of these nuclei that were also expressing BrdU was calculated. The proliferative effect of S1P was represented as a fraction of BrdU-positive nuclei per total nuclei on all microvessels expressing SMA.

3D Scaffold Fabrication

Microspheres of 85:15 PLAGA (MW = 100kDa, Lakeshore Biomaterials, Birmingham, AL) were fabricated using a single emulsion method. Briefly, 5 grams of polymer was dissolved in 20ml of methylene chloride. This dissolved polymer solution was slowly poured into a 0.1% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution already stirring at 1200rpm. This emulsion was allowed to stir constantly at 1200rpm for 24 hours, after which the solution was removed from the stirring apparatus and allowed to settle. Microspheres were removed by vacuum filtration, lyophilized, separated by size using a 50–300μm sorting sieve, and stored in a desiccator.

To fabricate 3D scaffolds, twenty 1mm 50:50 PLAGA films loaded with S1P (See above) (or unloaded to serve as the control) were mixed together with enough 85:15 PLAGA microspheres to fill individual circular copper molds measuring 8mm (diameter) by 1 mm (thickness). This mold design was chosen so that the scaffold would be appropriately sized for implantation into the critical-size cranial defect. All 3D microsphere-based scaffolds were sintered at 75°C for 3 hours in the circular copper molds. Following sintering, scaffolds were removed and stored in a desiccator for future use.

Rat Cranial Defect Model

Adult male retired breeders (400–550g) were randomly assigned to 2 different experimental groups: unloaded 3D scaffolds and S1P-loaded 3D scaffolds. The rat defect model used has been previously described [42]. Briefly, animals were anesthetized using 4.5mg/100g Nembutal via IP injection. Following anesthetization, the head was surgically prepped and mounted onto a stereotactic restraint. The skin was incised along the midline and the subcutaneous fascia was divided until the periosteal layer was revealed. The periosteum was reflected laterally. An 8mm diameter circular defect was excavated using a drill. Care was taken to avoid damage to the underlying dura mater tissue. Implants of choice (unloaded or S1P-loaded) were placed into the defect. The periosteum and skin were closed using running sutures. Following closure, both antibiotics and post-operative analgesics were administered for 1 week following surgery. All defect surgeries were performed according to an approved protocol from the UVa Animal Care and Use Committee.

X-ray Imaging Analysis

Following the last in vivo timepoint (either 14 or 42 days), the rats were euthanized and the defects excised and immediately placed into 10% formalin. Samples of the same implant type (unloaded or S1P-loaded) and same end timepoint (day 14 or 42) were placed chronologically across Kodak X-ray film. Samples were imaged for 6 sec at 12.5 kVp using a Hewlett Packard Faxitron (Series X-ray System, 43805N). The films were subsequently developed and placed into an Alpha Innotech imaging system (Fluor Chem IS-8800) to convert the x-ray films into digital image files.

MicroCT Imaging Analysis

New bone healing within the defect area was imaged using a quantitative microcomputed tomography (microCT) specimen imaging scanner (Scanco, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) after 0, 14, and 42 days. Animals were anesthetized by IP injection of 4.5mg/100g Nembutal. Subsequently, animals were imaged for 14 minutes utilizing a low resolution, 45 kVp scan. At end time-points, animals were sacrificed with an overdose of Nembutal, and ex vivo scans of each specimen were obtained utilizing a high resolution, 45 kVp scan. Following reconstruction of the 2D slices, an appropriate threshold matching the original grayscale images was chosen. Contour lines were drawn around the defect area to appropriately select a circular defect void volume (VOI) of 8mm × 1mm, taking care to exclude neighboring native bone. 3D images were created from 2D slices and the bone volume within the selected circular defect was calculated using the 3D evaluation program. Bone void volume, threshold (160), and scan parameters (support = 2, width = 1.2) were kept constant throughout the entire study.

Cranial bone histology

Following ex vivo x-ray imaging and ex vivo microCT scanning, each sample was placed into a histology cassette, labeled and decalcified using Richard Scientific Decalcifying Solution (Kalamazoo, MI) for 5 days at room temperature on a rotating rocker. Following decalcification, samples were dehydrated overnight. Samples were then cut along the coronal plane at the midline of the defect and embedded in paraffin. Twelve 7um sections per sample were mounted onto individual slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images were acquired using a x10 objective on an Axioskop 40 microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons were made using a one-way ANOVA. Diameter analysis was performed using a General Linear Model ANOVA with an unbalanced nested design, followed by Tukey’s test for pairwise comparisons. Significance was asserted at p < 0.05.

Results

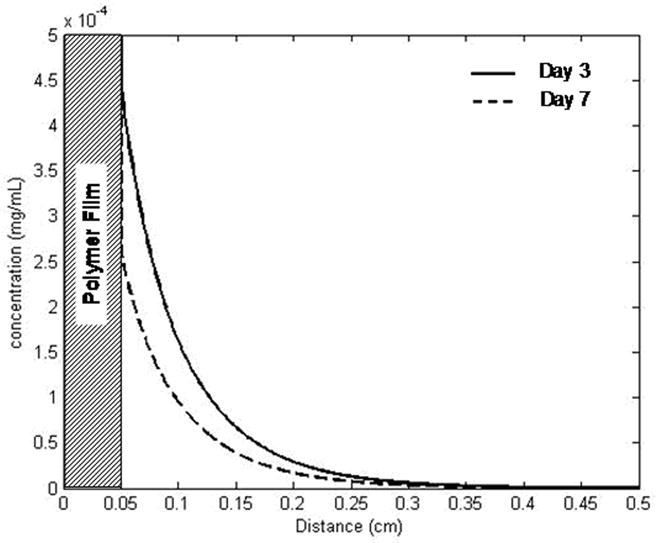

Diffusion Model of S1P Release

Mathematical modeling of S1P release from a single PLAGA film (diameter = 1 mm, height = 0.5 mm) predicted that therapeutically-relevant concentrations of S1P [22, 28] exist in the tissue space up to 2 mm away from the film edge. At 1 mm from the film edge, S1P concentration was predicted to be approximately 461 nM after 3 days and 264 nM after 7 days. At a distance of 2mm away, S1P concentration was predicted to be approximately 71 nM and 53 nM at day 3 and day 7, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mathematical diffusion model of S1P release from PLAGA film. With an initial loading of 1:400 (S1P:PLAGA), the concentration profile is displayed. S1P concentration at a distance of 1mm from the film is approximately 461nM (day 3) and 264nM (day 7). At a distance of 2mm, the maximum distance used in quantitative analysis, the [S1P] is about 71nM (day 3) and 53nM (day 7).

Microvascular remodeling in the dorsal skinfold window chamber

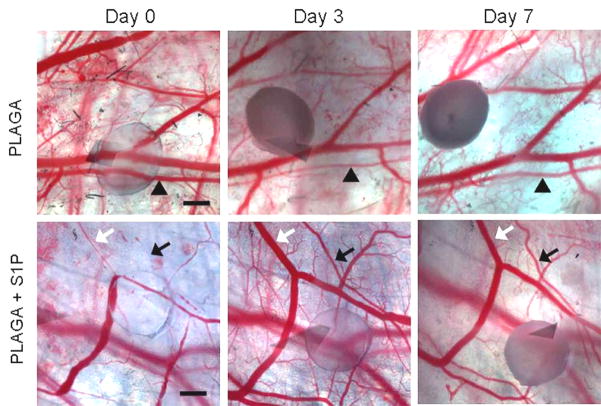

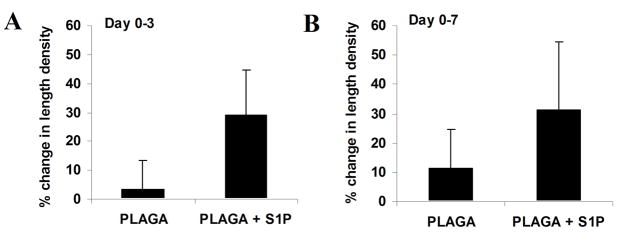

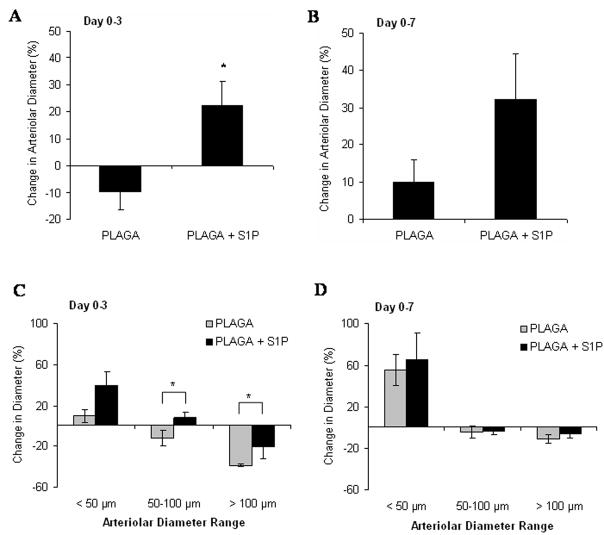

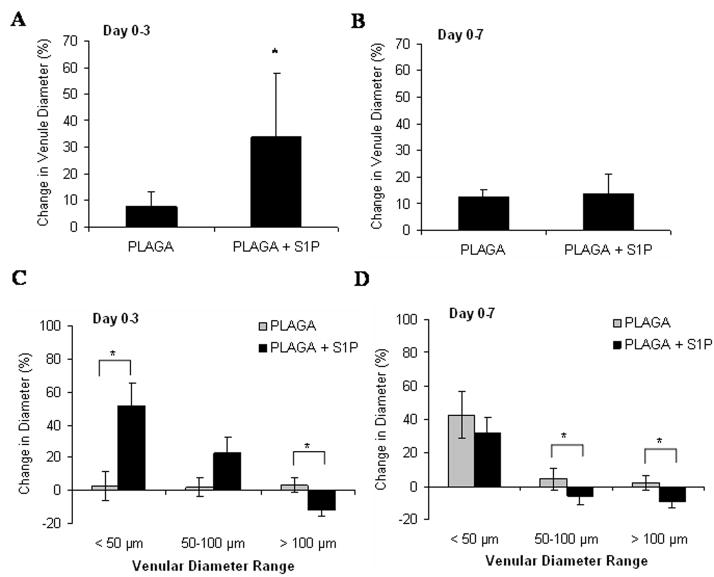

Intravital microscopy was used to track changes in microvascular remodeling over the course of 7 days. At 0, 3, and 7 days post-implantation of unloaded control films or S1P-loaded films, the dorsal window of each mouse was exposed, treated with a vasodilatory, and imaged en face. As demonstrated in the representative images in Figure 2, sustained release of S1P induced a lumenal diameter expansion of local arterioles and venules. Functional differences in total vessel length were quantified after 3 and 7 days of treatment with unloaded or S1P-loaded films. S1P elicited a moderate increase in length density over the control after both 3 and 7 days, although not significant (Figures 3). Lumenal expansion of both arterioles and venules was measured at 3 and 7 days post-implantation of unloaded or S1P-loaded films. S1P stimulated a significant increase in the lumenal diameter of arterioles after 3 days (Figure 4a). This arteriogenic response persisted for the entire 7 day time-course, although not statistically significant (Figure 4b). Additionally, in the first three days, arterioles with initial diameters less than 50μm underwent the greatest change in diameter expansion in response to S1P (40%), as compared to vessels in the other size ranges (50–100μm and >100μm) (Figure 4c). Arterioles 50–100μm in size significantly expanded in response to S1P, compared to the decrease in diameter observed in the control group after 3 days. Similar to the arteriolar response, S1P significantly increased the lumenal diameter of venules after 3 days of treatment (Figure 5a). However, venule expansion did not persist over 7 days, as there is no significant difference between control and S1P groups from days 0–7 (Figure 5b). Additionally, and similar to the case with arterioles, venules in the smallest size range (<50μm) demonstrated the greatest remodeling response (50%) in the first three days. Interestingly, S1P also caused a significant decrease in lumenal diameter of venules greater than 100μm that was maintained for 7 days (Figures 5c, 5d).

Figure 2.

Intravital microscopy images of control PLAGA films (top) or S1P loaded films (bottom) in the dorsal skinfold window chamber at 0, 3, and 7 days post-implantation. Substantial lumenal expansion of both arterioles (black) and venules (white) is induced by S1P over the course of 7 days (arrows). Changes in arteriole diameter in response to unloaded PLAGA control are negligible (arrowheads). Scale bar = 500 μm.

Figure 3.

Changes in microvascular length density following 3 (A) and 7 (B) days post-implantation of either 1mm PLAGA control films or PLAGA films loaded with S1P. Release of S1P enhanced vascular length density (a measure of total vessel length), although not significant.

Figure 4.

Changes in arteriolar diameter following 3 (A) and 7 (B) days post-implantation of either 1mm PLAGA control films or PLAGA films loaded with S1P. S1P significantly stimulated lumenal expansion of arterioles in the first three days of treatment (*p<0.05). Arterioles were grouped by the initial diameter measurement at day 0 (<50 μm, 50–100 μm, and >100 μm) and changes in microvessel diameter were tracked after 3 (C) and 7 (D) days.

Figure 5.

Changes in venular diameter following 3 (A) or 7 (B) days post-implantation of either 1mm PLAGA control films or PLAGA films loaded with S1P. Venules were grouped by the initial diameter measurement at day 0 (<50 μm, 50–100 μm, and >100 μm) and changes in diameter were assessed after 3 (C) and 7 (D) days. S1P stimulated the lumenal expansion of venules <50 μm in the first 3 days of treatment. A reduction in lumenal venular diameter occurred in vessels >100 μm in the first three days of treatment with S1P and was maintained over 7 days. (*p<0.05)

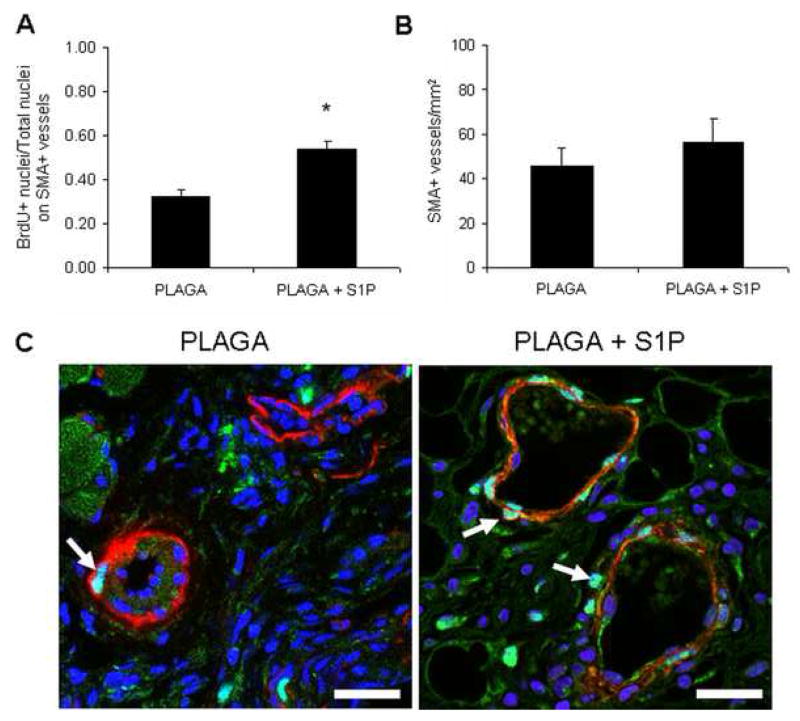

Analysis by Immunofluorescence

As a result of the robust arteriogenic response of microvessels stimulated with S1P, we interrogated potential changes in the proliferation of mural cells on these microvessels. Analysis by immunofluorescence for BrdU revealed a significant increase in the percentage of proliferating cells located on areterioles and venules expressing smooth muscle α-actin in S1P-treated tissue sections (Figure 6a, 6c). In contrast, there was no significant increase in the number of microvessels (defined as SMA-positive cells that formed an obvious lumen) per tissue section in response to S1P (Figure 6b), which is consistent with trends observed in length density measurements.

Figure 6.

Assessment of mural cell proliferation on expanding microvessels. A) Ratio of BrdU-positive nuclei per total nuclei stained with smooth muscle α-actin. S1P significantly enhances the number of proliferating cells found on microvessels, suggestive of an arteriogenic effect. B) Number of microvessels with smooth muscle α-actin-positive cells per tissue section. S1P did not significantly enhance the number of microvessels per area, consistent with length density analysis. C) Representative confocal microscopy images of smooth muscle α-actin-postive mural cells (red), cell nuclei (blue), or proliferating, BrdU-postive cell nuclei (green). S1P enhances the number of proliferating cells per vessel, demonstrated by colocalization of blue and green labeled nuclei (arrows). Scale bar = 25μm.

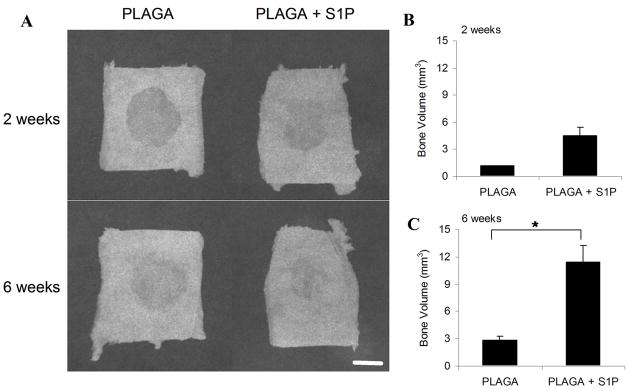

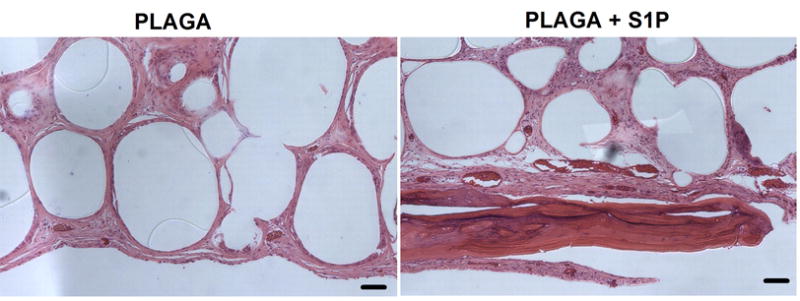

Bone healing in rat cranial defect model

To evaluate the ability of S1P delivery to enhance bone repair tissue engineering strategies, we implanted S1P-loaded 3D scaffolds into rat critical-size cranial defects and evaluated healing over a 6 week time-course. After both 2 and 6 weeks, quantitative microCT analysis confirmed a significantly greater amount of new bone volume in S1P-loaded constructs compared with unloaded controls (Figure 7b, 7c). Additionally, the amount of new bone formed in S1P-loaded groups increased from 2 to 6 weeks. New bone volume observed was located predominantly around the perimeter of the defect, as confirmed by 2D x-ray imaging (Figure 7a) and histological staining (Figure 8). H&E-stained histological sections confirmed greater amounts of bone healing in S1P-loaded defects and also revealed large numbers of microvessels near the formation of new bone tissue (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

A) Following 2 and 6 weeks of cranial bone healing, the defect and surrounding native bone were excised from the cranial defect site. X-ray imaging analysis was performed on each ex vivo sample. Representative images from each experimental group are shown (A). Scale bar = 4mm. New bone volume formed within defect area following 2 weeks (B) and 6 weeks (C) of healing. Values calculated from high resolution 3D reconstructed images acquired using ex vivo microCT scans of each sample. (*p<0.05)

Figure 8.

H&E staining of cranial defect histological sections after 6 weeks. Substantial bone healing and increased number of vessels observed in S1P-loaded scaffold groups (PLAGA + S1P), compared to PLAGA controls. Scale bar = 100μm.

Discussion

In this study, we show that sustained release of the bioactive phospholipid sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) promotes lumenal expansion of arterioles and venules by stimulating mural cell proliferation in the dorsal skinfold window chamber model in adult tissue. Additionally, sustained release of S1P enhances new bone and microvessel formation in a model of bone repair. Thus, the present study demonstrates that controlled delivery of S1P can be utilized as a therapeutic arteriogenic agent to promote microvessel diameter expansion and tissue-engineered healing of bone.

Biodegradable poly(α-hydroxy ester) polymers, including poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLAGA), have been used extensively for fabrication of 3D scaffold biomaterials utilized in tissue engineering due to their commercial availability, excellent biocompatibility, and prior FDA approval for a number of clinical applications [43]. These synthetic biomaterials can circumvent limitations of systemic delivery by sustaining release and bioavailability of a growth factor within target tissues without systemic and/or dose-related toxicity. To this end, we encapsulated S1P into polymeric thin films of PLAGA and approximated the release kinetics of S1P diffusing out of the polymer and into the tissue space using a mathematical model (Figure 1). Results of the model suggest that S1P is released from our polymer system in concentrations known to stimulate endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in vitro [22, 28]. Additionally, the concentration profile is predicted to persist to a distance 2mm away from the film edge. For this reason, we analyzed the microvasculature contained in a 2mm concentric radius around the film in the dorsal window chamber studies. Enlargement of arteriolar and venular diameters is seen within the first three days of treatment with S1P-loaded films, suggesting a therapeutically-relevant concentration of S1P is available in the tissue; however, after 7 days, the enlargement is no longer significant over control (Figures 4, 5). One possible explanation for this reduction is a low concentration of S1P in the tissue space, as S1P has a reported half-life of only 2 hours in the bloodstream [41]. Once it is released from our polymer, S1P enters the sphingomyelinase pathway where it can be dephosphorylated by sphingosine phosphatase to sphingosine or terminally cleaved by S1P lyase. Sphingosine can then either be reacylated to ceramide or phosphorylated through the actions of sphingosine kinase (SphK) to generate S1P [44]. Studies with radioactive S1P reported that the bioactive lipid is rapidly degraded in the presence of smooth muscle cells to radioactive sphingosine, ceramide, and sphingomyelin [26,29,45,46]. Furthermore, S1P is insoluble in aqueous solutions in the absence of a carrier protein, such as albumin [40]. To gain a better understanding of the fate of S1P in our tissue after release from PLAGA, the concentrations of sphingosine phosphatase, kinase, and lyase, as well as albumin, must be determined in vivo. Future studies utilizing radiolabeled S1P must also be performed to quantify the release of S1P from our polymer system.

The role of S1P and other phospholipids in stimulating adult microvascular remodeling in vivo has been largely understudied. In one report, S1P release from hydrogels was shown to stimulate angiogenesis in a chick CAM assay [26]. Most recently, a second study demonstrated that exogenous administration of S1P stimulated blood flow recovery, accompanied by an increase in capillary density, in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia [47]. In this study, the dorsal skinfold window chamber model was selected because of its rigorous assessment of vascular changes; the same vessels can be tracked over time to yield quantitative results of total vessel length or diameter. Although S1P has been well-documented to stimulate endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation in vitro, cell behaviors indicative of an angiogenic phenotype, we did not see significant increases in length density, a metric of total microvascular length after 3 or 7 days (Figure 3). Despite model predictions of S1P concentration in the tissue space, the amount of albumin in solution could control the rate of release from polymer; results from a CAM assay of angiogenesis showed, at best, a moderate increase in capillary sprouting with S1P-loaded hydrogels (5 nmol), but a statistically significant increase in angiogenesis when 5 nmol S1P was co-encapsulated with fatty-acid free (FAF) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in the hydrogels [26]. These results suggest that the transport of S1P is facilitated by lipid carriers and further studies are warranted to optimize the encapsulation of S1P in PLAGA for applications of sustained release.

In this study, we report on S1P’s arteriogenic potential in vivo, as demonstrated by significant increases in the diameter of resistance arterioles and supported by elevated BrdU incorporation within mural cells treated with S1P. Additionally, we report on a novel delivery strategy that allows for the sustained, local release of S1P and obviates the invasive delivery strategy of multiple exogenous injections. We demonstrate that release of S1P significantly increases the lumenal diameter of existing arterioles after 3 days and moderately expands arterioles after 7 days (Figure 4). Further interrogation into the size of arterioles undergoing lumenal expansion reveals that the smallest arterioles (< 50μm) exhibited the largest percent increase in diameter in the first three days, but this size-specific difference was abated by day 7. Interestingly, S1P also expands arterioles 50–100μm in size, in contrast to the decrease in size observed in control groups, making S1P an attractive candidate for increasing the size, and therefore the blood flow, to areas of tissue ischemia for all levels of microvascular networks. In contrast to arterioles, the significance of venular remodeling remains understudied, although it is thought that post-capillary venules are important for regulation of interstitial fluid [48]. These studies demonstrate that S1P also significantly increases venular diameter after 3 days of stimulation over control, but this effect is abated by day 7 as the percent change in diameter of venules in both S1P-treated and control groups are nearly identical (Figure 5). Similar to arteriolar expansion, venules in the smallest size range (< 50μm) exhibited the greatest increase in lumenal diameter. We suggest that the overall increase in venule diameter in the first three days may serve to provide insulted or diseased tissue with increased efflux of waste products.

As a result of S1P stimulating lumenal expansion of microvessels, we hypothesized that S1P would increase the number of proliferating cells on arterioles and venules. BrdU incorporation into the mice after 7 days reveals increased numbers of proliferating cells on microvessels with smooth muscle α-actin-stained mural cells in the S1P-treated group (Figure 6). Consistent with our observations in length density changes, histological analysis shows a moderate, but not statistically significant, increase in the total number of microvessels with smooth muscle α-actin-stained mural cells per tissue section area in response to S1P (Figure 6). Overall, histological analysis confirms our quantitative assessment of microvascular remodeling and suggests that S1P be utilized as a therapeutic arteriogenic agent to mature pre-existing vascular networks or nascent capillary networks formed in response to potent angiogenic factors.

The development and incorporation of mature microvascular networks is an important process with the potential to treat a variety of disease pathologies, including the tissue-engineered healing of bone. Thus, we investigate the ability of sustained S1P delivery to enhance new bone growth and microvascular remodeling within a critical-size osseous defect. Localized release of S1P from 3D biodegradable scaffolds significantly enhances the formation of new bone within the defect area after both 2 and 6 weeks of healing (Figure 7). Furthermore, histological analysis after 6 weeks suggests an increase in the number of blood vessels surrounding the islands of new bone formation, compared to PLAGA control scaffolds (Figure 8). Blood vessels are well-known to be key contributors to the process of osteogenesis, both in development and during repair [49–51]. Angiogenesis is thought to temporally precede osteogenesis [52], as predicted by the earliest studies of bone development [49]. To this end, we hypothesize that S1P’s observed ability to remodel the microvasculature, as demonstrated in the dorsal skinfold window chamber studies, combined with S1P’s reported ability to stimulate migration and proliferation of osteoblast precursor cells [34,53,54], which are critical to the formation of new bone, stimulates the formation of new bone in a model of cranial repair. Further studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between S1P signaling and bone remodeling, but these studies provide firm evidence that S1P-induced microvascular remodeling is a stimulus for the enhanced tissue-engineered healing of osseous defects.

Conclusions

Delivery of S1P from polymeric films was examined in an adult model of microvascular remodeling; S1P moderately increased the total length of microvessels and significantly enhanced lumenal diameter of both arterioles and venules in the first 3 days of treatment by stimulating mural cell proliferation, suggesting the effects of S1P may be more arteriogenic than angiogenic in this model of healthy adult tissue. Furthermore, sustained delivery of S1P significantly stimulated new bone formation, accompanied by an increased presence of vasculature, in a cranial model of bone repair. Taken together, these experiments support S1P as a player in vascular maturation and highlight its potential use as a therapeutic agent for promoting arteriogenesis, specifically in applications of tissue-engineered bone repair, wound healing, or ischemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Roy Ogle for his scientific expertise in the cranial defect model and Dr. Sunil Tholpady and Ashok Tholpady for their assistance with the cranial defect surgeries. This study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant AR-052352-01A1. Lauren Sefcik is supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, Caren Petrie Aronin by the University of Virginia Biotechnology Training Program grant 5T32GM008715-08, and Kristen Wieghaus by the U.S. Department of Education’s Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need funding.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lauren S. Sefcik, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Virginia, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville, VA 22908.

Caren E. Petrie Aronin, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Virginia, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville, VA 22908.

Kristen A. Wieghaus, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Virginia, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville, VA 22908

Edward A. Botchwey, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Virginia, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville, VA 22908, Tel: 434-243-9846, Fax: 434-982-3870, botchwey@virginia.edu

References

- 1.Griffith CK, Miller C, Sainson RCA. Diffusion limits of an in vitro thick prevascularized tissue. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(1–2):257–66. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wieghaus KA, Capitosti SM, Anderson CR, Price RJ, Blackman BB, Brown ML, et al. Small molecule inducers of angiogenesis for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(7):1903–13. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botchwey EA, Dupree MA, Pollack SR, Levine EM, Laurencin CT. Tissue engineered bone: measurement of nutrient transport in three-dimensional matrices. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67(1):357–67. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershey JC, Baskin EP, Corcoran HA, Bett A, Dougherty NM, Gilberto DB, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates angiogenesis without improving collateral blood flow following hindlimb ischemia in rabbits. Heart and Vessels. 2003;18(3):142–9. doi: 10.1007/s00380-003-0694-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziche M, Donnini S, Morbidelli L. Development of new drugs in angiogenesis. Curr Drug Targets. 2004;5(5):485–93. doi: 10.2174/1389450043345371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry TD, Annex BH, McKendall GR, Azrin MA, Lopez JJ, Giordano FJ, et al. The VIVA trial: vascular endothelial growth factor in ischemia for vascular angiogenesis. Circulation. 2003;107(10):1359–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061911.47710.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeshita S, Zheng LP, Brogi E, Kearney M, Pu LQ, Bunting S, et al. Therapeutic Angiogenesis - a Single Intraarterial Bolus of Vascular Endothelial Growth-Factor Augments Revascularization in a Rabbit Ischemic Hind-Limb Model. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(2):662–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI117018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva EA, Mooney DJ. Spatiotemporal control of vascular endothelial growth factor delivery from injectable hydrogels enhances angiogenesis. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(3):590–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zisch AH, Lutolf MP, Ehrbar M, Raeber GP, Rizzi SC, Davies N, et al. Cell-demanded release of VEGF from synthetic, biointeractive cell-ingrowth matrices for vascularized tissue growth. Faseb J. 2003;17(15):2260–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1041fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peirce SM, Skalak TC. Microvascular remodeling: a complex continuum spanning angiogenesis to arteriogenesis. Microcirculation. 2003;10(1):99–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peirce SM, Price RJ, Skalak TC. Spatial and temporal control of angiogenesis and arterialization using focal applications of VEGF164 and Ang-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004a;286(3):H918–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00833.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peirce SM, Van Gieson EJ, Skalak TC. Multicellular simulation predicts microvascular patterning and in silico tissue assembly. Faseb J. 2004b;18(6):731–3. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0933fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain RK. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):685–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):389–95. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heil M, Schaper W. Insights into pathways of arteriogenesis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2007;8(1):35–42. doi: 10.2174/138920107779941408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson TP, Peters MC, Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Polymeric System for Dual Growth Factor Delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19(11):1029–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen RR, Silva EA, Yuen WW, Mooney DJ. Spatio-temporal VEGF and PDGF delivery patterns blood vessel formation and maturation. Pharm Res. 2007;24(2):258–64. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnard GC, McCool JD, Wood DW, Gerngross TU. Integrated recombinant protein expression and purification platform based on ralstonia eutropha. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(10):5735–42. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5735-5742.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Van Brocklyn JR, Hobson JP, Movafagh S, Zukowska-Grojec Z, Milstien S, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates cell migration through a G(i)-coupled cell surface receptor - Potential involvement in angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(50):35343–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura T, Watanabe T, Sato K, Kon J, Tomura H, Tamama K, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates proliferation and migration of human endothelial cells possibly through the lipid receptors, Edg-1 and Edg-3. Biochem J. 2000;348(1):71–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kluk MJ, Hla T. Role of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor EDG-1 in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Circ Res. 2001;89(6):496–502. doi: 10.1161/hh1801.096338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lockman K, Hinson JS, Medlin MD, Morris D, Taylor JM, Mack CP. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates smooth muscle cell differentiation and proliferation by activating separate serum response factor co-factors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(41):42422–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anliker B, Chun J. Lysophospholipid G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(20):20555–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pyne S, Pyne N. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling via the endothelial differentiation gene family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;88(2):115–31. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee OH, Kim YM, Lee YM, Moon EJ, Lee DJ, Kim JH, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces angiogenesis: its angiogenic action and signaling mechanism in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264(3):743–50. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wacker BK, Scott EA, Kaneda MM, Alford SK, Elbert DL. Delivery of sphingosine 1-phosphate from poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(4):1335–43. doi: 10.1021/bm050948r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allende ML, Yamashita T, Proia RL. G-protein-coupled receptor S1P1 acts within endothelial cells to regulate vascular maturation. Blood. 2003;102(10):3665–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H, Goetzl EJ, An SZ. Lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulate endothelial cell wound healing. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278(3):C612–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura T, Sato K, Malchinkhuu E, Tomura H, Tamama K, Kuwabara A, et al. High-density lipoprotein stimulates endothelial cell migration and survival through sphingosine 1-phosphate and its receptors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(7):1283–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000079011.67194.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hisano N, Yatomi Y, Satoh K, Akimoto S, Mitsumata M, Fujino MA, et al. Induction and suppression of endothelial cell apoptosis by sphingolipids: A possible in vitro model for cell-cell interactions between platelets and endothelial cells. Blood. 1999;93(12):4293–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paik JH, Skoura A, Chae SS, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of N-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization. Genes & Development. 2004;18(19):2392–403. doi: 10.1101/gad.1227804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, Mi Y, Deng CX, Hobson JP, et al. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(8):951–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsiong SX, Mooney DJ. Regeneration of vascularized bone. Periodontol 2000. 2006;41:109–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grey A, Xu X, Hill B, Watson M, Callon K, Reid IR, et al. Osteoblastic cells express phospholipid receptors and phosphatases and proliferate in response to sphingosine 1-phosphate. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;74(6):542–50. doi: 10.1007/s00223-003-0155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grey A, Chen Q, Callon K, Xu X, Reid IR, Cornish J. The phospholipids sphingosine 1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid prevent apoptosis in osteoblastic cells via a signaling pathway involving G(i) proteins and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. Endocrinology. 2002;143(12):4755–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bittner B, Witt C, Mäder K, Kissel T. Degradation and protein release properties of microspheres prepared from biodegradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) and ABA triblock copolymers: influence of buffer media on polymer erosion and bovine serum albumin release. J Control Release. 1999;60(2–3):297–309. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faisant N, Akiki J, Siepmann F, Benoit JP, Siepmann J. Effects of the type of release medium on drug release from PLGA-based microparticles: experiment and theory. Int J Pharm. 2006;314(2):189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skerjanec A, Tedesco H, Neumayer HH, Cole E, Budde K, Hsu CH, et al. FTY720, a novel immunomodulator in de novo kidney transplant patients: pharmacokinetics and exposure-response relationship. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(11):1268–78. doi: 10.1177/0091270005279799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nofer JR, Bot M, Brodde M, Taylor PJ, Salm P, Brinkmann V, et al. FTY720, a synthetic sphingosine 1-phosphate analogue, inhibits development of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2007;115(4):501–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.641407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosen H, Liao J. Sphingosine 1-phosphate pathway therapeutics: a lipid ligand-receptor paradigm. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7(4):461–8. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, McVerry BJ, Burne MJ, Rabb H, et al. Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(11):1245–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1258OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrie Aronin CE, Sadik KW, Lay AL, Rion DB, Tholpady SS, Ogle RC, et al. Comparative effects of scaffold pore size, pore volume, and total void volume on cranial bone healing patterns using microsphere-based scaffolds. J Biomed Mat Res Part A. 2008 doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32015. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agrawal C, Niederauer G, Athanasiou K. Fabrication and characterization of PLA-PGA orthopaedic implants. Tissue Eng. 1995;1(3):241–52. doi: 10.1089/ten.1995.1.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saba JD, Hla T. Point-Counterpoint of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Metabolism. Circ Res. 2004;94:724–34. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122383.60368.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yatomi Y. Sphingosine 1-phosphate in vascular biology: possible therapeutic strategies to control vascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(5):575–87. doi: 10.2174/138161206775474404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Budde K, Schmouder RL, Brunkhorst R, Nashan B, Lucker PW, Mayer T, et al. First human trial of FTY720, a novel immunomodulator, in stable renal transplant patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(4):1073–83. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1341073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oyama O, Sugimoto N, Qi X, Takuwa N, Mizugishi K, Koisumi J, et al. The lysophospholipid mediator sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes angiogenesis in vivo in ischemic hindlimbs of mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2008 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn002. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aukland K, Nicolaysen G. Interstitial fluid volume: local regulatory mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 1981;61(3):556–643. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trueta J. The role of the vessels in osteogenesis. J Bone Jt Surg Ser A. 1963;45B(2):402. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glowacki J. Angiogenesis in fracture repair. Clin Orthop. 1998;355:S82–9. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hausman MR, Schaffler MB, Majeska RJ. Prevention of fracture healing in rats by an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Bone. 2001;29(6):560–4. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00608-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winet H, Bao JY, Moffat RA. A control model for tibial cortex neovascularization in the bone chamber. J Bone Min Res. 1990;5(1):19–30. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dziak R, Yang BM, Leung BW, Li S, Marzec N, Margarone J, et al. Effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid on human osteoblastic cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;68(3):239–49. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(02)00277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryu J, Kim HJ, Chang EJ, Huang H, Banno Y, Kim HH. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a regulator of osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast-osteoblast coupling. EMBO J. 2006;25:5840–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]