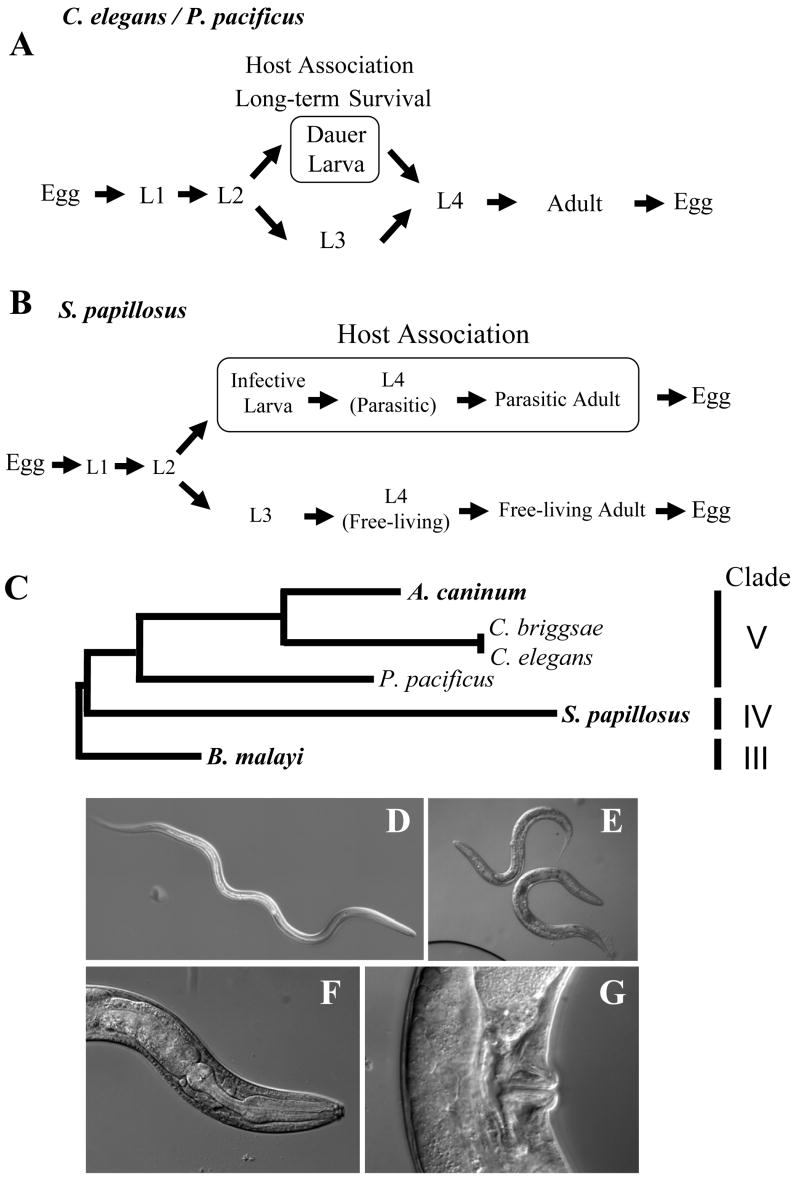

Fig. 1.

(A) Life cycles of the free-living nematodes C. elegans and P. pacificus. Under favorable conditions, animals go through direct development (L1-L4). In the laboratory, one cycle takes as little as 3-4 days (20° C). Under unfavorable conditions, such as high temperature, high population density or starvation, animals can go into the arrested dauer stage. Note that the importance of the dauer larvae for host association is best known for P. pacificus and its beetle association. (B) A simplified scheme for the life cycle of the vertebrate parasite Strongyloides papillosus. Note that not only the third larval stage, but also the fourth larval stage and the adult stage are specialized for each life style. For a more precise representation of S. papillosus life cycle, see Figure S2. (C) Phylogenetic relationship of the three species used in this study (P. pacificus, C. elegans and S. papillosus), with three other taxa C. briggsae, the hookworm A. caninum, and B. malayi. Parasitic species are indicated in bold. (D) Overall morphology of a S. papillosus infective larva. E-G Phenotype of Δ7-DA-treated progeny S. papillosus that show morphological characteristics of free-living adults. (E) Overall morphology of free-living adults. (F) Rhabdiform esophagus with a grinder in the pharynx, which is only known from free-living adults but not parasitic females. (G) Vulva opening in the mid-body region, a feature that is also only known from free-living females.