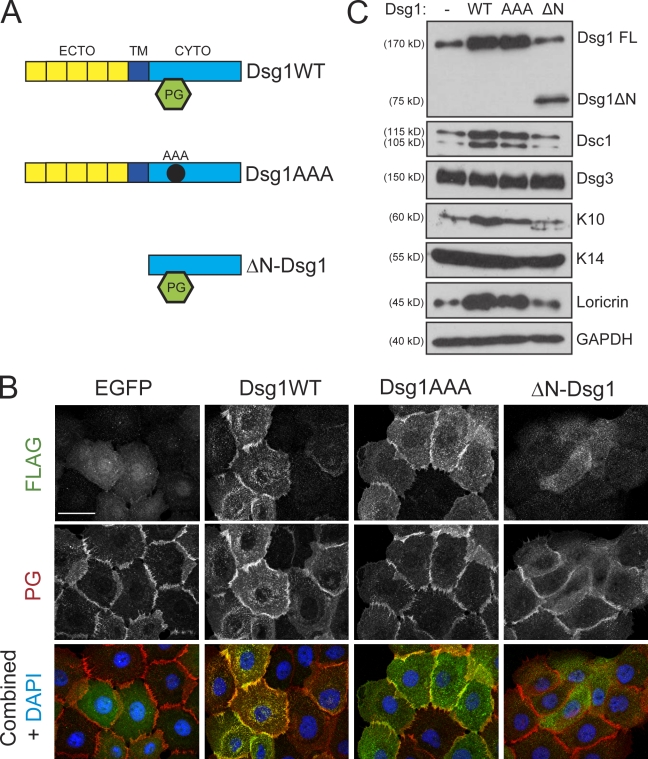

Figure 6.

Dsg1 promotes differentiation in the absence of robust PG binding. (A) To test which domains of Dsg1 would be sufficient to drive differentiation, we generated three Flag-tagged Dsg1 cDNA constructs: WT Dsg1 (Dsg1WT), a triple point mutant harboring three Ala substitutions (Dsg1AAA) within the predicted binding region for PG, or a truncation mutant lacking the ectodomain (ECTO) and transmembrane (TM) region (ΔN-Dsg1). CYTO, cytoplasmic domain. (B) The subcellular localization of Dsg1WT, Dsg1AAA, or ΔN-Dsg1 was determined in keratinocytes immunostained using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against Flag and a chicken polyclonal antibody against PG after exposing cells to high Ca2+ for 4 h to induce junction assembly. Both Dsg1WT and Dsg1AAA were efficiently recruited to areas of cell–cell contact; however, ΔN-Dsg1 was diffusely distributed throughout the cytoplasm. PG staining highlighted the intercellular borders; its localization at junctions was largely unaffected by any of the Dsg1 constructs. (C) Western blot analysis of keratinocytes transduced with these Dsg1 constructs and induced to differentiate for 2 d as submerged cultures. Although Dsg1WT and Dsg1AAA were sufficient to increase Dsc1/K10/loricrin, ΔN-Dsg1 did not affect these markers of differentiation compared with EGFP-transduced (Dsg1−) control cultures. FL, full length; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Bar, 20 µm.