Abstract

PURPOSE Studies suggest peer-led self-management training improves chronic illness outcomes by enhancing illness management self-efficacy. Limitations of most studies, however, include use of multiple outcome measures without predesignated primary outcomes and lack of randomized follow-up beyond 6 months. We conducted a 1-year randomized controlled trial of Homing in on Health (HIOH), a Chronic Disease Self-Management Program variant, addressing these limitations.

METHODS We randomized outpatients (N = 415) aged 40 years and older and who had 1 or more of 6 common chronic illnesses, plus functional impairment, to HIOH delivered in homes or by telephone for 6 weeks or to usual care. Primary outcomes were the Medical Outcomes Study 36-ltem short-form health survey‘s physical component (PCS-36) and mental component (MCS-36) summary scores. Secondary outcomes included the EuroQol EQ-5D and visual analog scale (EQ VAS), hospitalizations, and health care expenditures.

RESULTS Compared with usual care, HIOH delivered in the home led to significantly higher illness management self-efficacy at 6 weeks (effect size = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10–0.43) and at 6 months (0.17; 95% CI, 0.01–0.33), but not at 1 year. In-home HIOH had no significant effects on PCS-36 or MCS-36 scores and led to improvement in only 1 secondary outcome, the EQ VAS (1-year effect size = 0.40; CI, 0.14–0.66). HIOH delivered by telephone had no significant effects on any outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS Despite leading to improvements in self-efficacy comparable to those in other CDSMP studies, in-home HIOH had a limited sustained effect on only 1 secondary health status measure and no effect on utilization. These findings question the cost-effectiveness of peer-led illness self-management training from the health system perspective.

Keywords: Chronic disease, self care, chronic disease self-management program, health status, randomized controlled trial, self-efficacy, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Interventions to help patients manage health conditions have potential as cost-effective ways to improve chronic illness outcomes.1–3 Research supports the peer-led Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP), which aims to enhance self-efficacy or confidence to execute illness management behaviors, regardless of specific diagnosis.4 In randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the original CDSMP5,6 and several variants7–11 improved illness management self-efficacy and some subfacets of health status. In 2 studies, the program also reduced hospitalizations.5,8

Prior studies of the CDSMP have several limitations, however. Most used multiple outcomes without predesignated primary outcomes. Thus, the varied and inconsistent effects observed among studies may, in part, reflect chance findings as a result of multiple outcomes testing. Additionally, only 1 study observed participants in a randomized fashion for more than 6 months. That study, involving an Internet variant of the program, found a small effect on health distress at 1 year but no significant effects on self-efficacy, health status, or utilization.10 Finally, not all RCTs of the CDSMP had positive findings.12,13

Thus, it is unclear whether the CDSMP improves utilization beyond 6 months, or whether it improves scores on robust measures of overall mental and physical health status at any interval. Such outcomes are important to the clinicians, policy makers, and administrators who must decide whether to allocate limited resources to peer-led self-management programs.

To address these questions, we conducted a 1-year RCT of Homing in on Health (HIOH), a one-on-one, home-delivered variant of the CDSMP. The original CDSMP is provided to small groups in centralized locations. We aimed to make its content available to those less able to participate because of functional limitations, transportation problems, and/or discomfort with groups. We explored telephone delivery because it has been used to provide other successful peer interventions at reduced cost.14–16

We hypothesized that, compared with a control group receiving usual care, patients receiving HIOH would have significantly better illness management self-efficacy for 1 year, leading to more effective self-management and, therefore, better overall physical and mental health status and fewer hospitalizations and health care expenditures at 1 year. We also hypothesized there would be no significant differences in outcomes between the intervention groups. Based on previous research,15,17–26 we also explored whether HIOH patients who had a greater number of depressive symptoms would experience greater improvements in these outcomes at 1 year than would those with fewer depressive symptoms.

METHODS

Study activities were conducted from July 2004 through February 2008. The local Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Setting, Recruitment, and Randomization

Power calculations were based on a minimal clinically important difference of 3 points in the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) physical component (PCS-36) and mental component (MCS-36) summary scores.27 We conservatively assigned a 2-point minimal clinically important difference in calculations, approximating an intervention effect size of 0.2 (small effect).28 Accounting for possible attrition up to 10%, with an α of .05, we estimated that 120 patients per group would provide an 80% power to detect a 2-point difference in scores.

Study patients were recruited from the 12 offices of a university-affiliated primary care network in Northern California. Our target study population was patients aged 40 years or older who had 1 or more of the following: arthritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, depression, and/or diabetes mellitus. We recruited patients with these criteria by means of announcements and telephone calls.

The study coordinator screened interested patients for additional eligibility criteria: ability to speak and read English, residence in a private home with an active telephone, eyesight and hearing adequate to participate, and at least 1 activity impairment assessed by the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)29 and/or a score of 4 points or greater (at least mild depressive symptoms) on the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).30

A study nurse visited eligible participants at their homes to obtain informed consent, administer the baseline study questionnaire, and implement randomized allocation in blocks of 12 participants using sealed opaque envelopes containing group assignments. Participants received a $25 retail store gift card after each of 5 scheduled follow-up data collection telephone calls.

Procedures

Study Intervention

The CDSMP has been described in detail previously.4,5,31 Using a standardized script and highly interactive format, participants’ peers who were not health care clinicians and who had personal experience with chronic conditions delivered the CDSMP to groups of 10 to 15 participants in 6 weekly sessions lasting approximately 2 hours each. The overall aim was mastery of fundamental self-management tasks,31 with frequent opportunities provided to practice and receive feedback on performance of various tasks, as a way of fostering increased illness management self-efficacy, the putative mediator of the CDSMP’s effects.31 Specific topics included exercising safely, coping with difficult emotions, and using cognitive symptom management techniques.

HIOH was almost identical to the CDSMP in content. The developers of the CDSMP provided the study investigators with an electronic copy of the CDSMP intervention script to which only few and minor content changes were made. Whereas the CDSMP is provided by pairs of peer facilitators to small groups of participants in central facilities, HIOH was delivered one-on-one in patients’ homes or by telephone. Four peers underwent week-long training before delivering the HIOH intervention. The training was analogous to that provided to peers before delivering the original CDSMP.

Each peer provided all 6 intervention sessions to their assigned participants. The same intervention script was used for both intervention groups. The study nurse audited the fidelity of intervention sessions on a scheduled, quarterly basis, providing formative feedback as indicated. Peers also completed a written log indicating whether and for how long they covered each scripted teaching point.

Usual-Care (Control) Group

These participants were initially visited in their home by the study nurse, as described for intervention participants, and completed the same follow-up telephone questionnaires. They otherwise received care from their usual clinicians.

Measures

At baseline, participants answered various sociodemographic questions. Unless noted, other measures were administered at baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

We assessed illness management self-efficacy as a measure of the effectiveness of delivery of the intervention content by means of a validated 33-item measure (composite Cronbach’s α = .96).32 Respondents rated their confidence for performing social activities, coping with symptoms, and dealing with other tasks on a 10-point Likert scale.

Health status was primarily assessed using the SF-36.33,34 The main study outcomes were the MCS-36 and PCS-36 summary scores.35 Both were designed so a representative population sample would have a mean score of 50 with a standard deviation of 10.

We also explored intervention effects on several secondary health status measures. The first was the Medical Outcomes Study 5-item general health (GH) subscale,36 included to facilitate comparisons with previous CDSMP studies, most of which used similar health status measures. Scores for all 3 SF-36 measures range from 0 to 100 (higher scores = better health).

Participants also completed 2 EuroQol (EQ) health status measures.37 We included the first, the preference-based EQ-5D, to facilitate potential cost-effectiveness analyses. Respondents rated problems with mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression as of the day of assessment using a 3-category scale (no, some, extreme problems). Responses were summed and converted into a summary index by applying scores from population-based valuation sets.38 We included the second, the Visual Analog Scale (EQ VAS), because it appears more responsive to small, yet possibly clinically significant, changes than to other health status measures.39–43 Participants indicated their overall health on the day of assessment from 0 to 100 (worst to best imaginable).

Other secondary measures included functional ability, measured with the 20-item HAQ (composite α = .92).29 Respondents rate difficulty in performing various activities (eg, dressing and grooming) on a 4-point Likert scale. Item scores were summed and divided by 60 to yield a total score (range 0–1, higher scores = poorer ability); depressive symptoms were measured with the 10-item CES-D (composite α = .87).30 Though no depressive symptom burden categories exist for chronically ill individuals, earlier studies suggest the following: 0 to 9 (low), 10 to 14 (moderate), and 15 to 30 (high).44–46

Using a validated questionnaire,47,48 we assessed medication adherence for the 7 days preceding data collection. Finally, we examined hospitalizations and total health care expenditures through 14 months from baseline. Office and emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and skilled nursing facility stays were ascertained from resource management reports. Expenditures were calculated using Medicare reimbursement formulas49,50 and, for medications, manufacturers’ average wholesale prices.51

Analyses

Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) was used for analyses. We examined intervention effects on outcomes measured at more than 1 time-point using a series of mixed-effects linear models for repeated measures.52 The outcome of interest at each time point was the dependent variable; study group, time of each outcome measurement (baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year), and the interaction between time and study group were the independent variables. The mixed-effects model adjusted for nesting of each outcome within each participant by means of random intercepts. Because we were primarily examining change in outcomes, no fixed baseline covariates were included.

For the hospitalization outcome, logistic regression was used, with group as the key independent variable, and age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, insurance status, baseline MCS-36, and PCS-36 as covariates. For the total expenditures outcome, a generalized linear model was used, with a γ distribution and log link, and the same independent variables as for the hospitalization outcome.

RESULTS

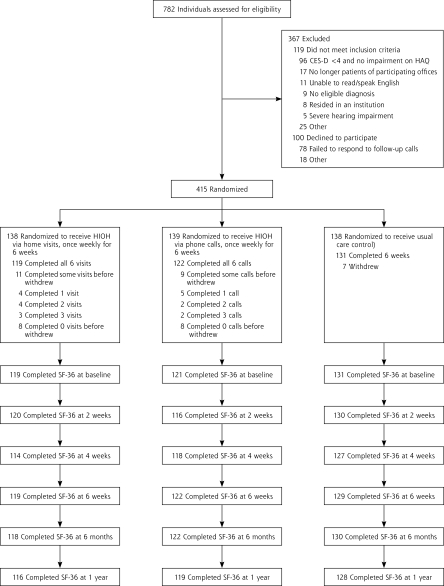

Figure 1 ▶ displays the flow of participants through the RCT. Table 1 ▶ displays a summary of participants’ baseline characteristics. Other than sessions missed by early dropouts, 100% of HIOH intervention sessions were completed. Table 2 ▶ summarizes outcomes by study group.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

CES-9 = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, 10-item version; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire; HIOH = Homing in on Health; SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants by Study Group

| Characteristic | Home (n=138) | Telephone (n=139) | Usual Care (n=138) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 59.8 (11.2) | 61.2 (11.6) | 60.1 (11.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 108 (78) | 109 (78) | 104 (75) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 103 (75) | 110 (79) | 115 (83) |

| Black | 20 (15) | 11 (8) | 15 (11) |

| Other | 14 (9) | 14 (10) | 7 (5) |

| Declined to answer | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| High school or less | 19 (14) | 20(14) | 22 (16) |

| Some college | 53 (38) | 50 (36) | 58 (42) |

| College graduate or greater | 66 (47) | 65 (47) | 57 (41) |

| Declined to answer | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Income level, n (%) | |||

| <40,000 | 41 (30) | 42 (31) | 44 (32) |

| 40,000–79,999 | 42 (30) | 37 (27) | 43 (31) |

| >80,000 | 22 (16) | 27 (20) | 22 (16) |

| Declined to answer | 33 (24) | 33 (24) | 29 (21) |

| Married, n (%) | 79 (57) | 79 (57) | 76 (55) |

| Chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 55 (40) | 72 (51) | 43 (31) |

| 2 | 51 (37) | 40 (29) | 65 (47) |

| 3 | 18 (13) | 21 (15) | 21 (15) |

| >4 | 14 (10) | 6 (4) | 9 (7) |

| Self-reported diagnoses, n (%)a | |||

| Arthritis | 83 (60) | 73 (52) | 77 (55) |

| Depression | 59 (43) | 64 (46) | 70 (51) |

| Diabetes | 64 (46) | 50 (36) | 58 (42) |

| Asthma | 34 (25) | 25 (18) | 39 (28) |

| Chronic lung disease | 15 (11) | 11 (8) | 17(12) |

| Congestive heart failure | 17 (12) | 17 (12) | 14 (10) |

| Uninsured, n (%) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Baseline status of outcomes, mean score (SD) | |||

| Self-efficacy | 7.0 (1.8) | 7.0 (1.7) | 7.1 (1.8) |

| PCS-36 | 33.6 (12.0) | 33.3 (12.4) | 34.4 (11.0) |

| MCS-36 | 45.6 (14.2) | 45.3 (13.7) | 45.8 (13.7) |

| GH | 47.2 (22.0) | 48.1 (24.9) | 50.2 (23.2) |

| EQ-5D | 0.74 (0.18) | 0.73 (0.18) | 0.75 (0.16) |

| EQ VAS | 64.3 (18.5) | 66.6 (19.1) | 68.4 (18.6) |

| HAQ | 0.92 (0.68) | 0.85 (0.74) | 0.82 (0.65) |

| CES-D | 9.5 (7.1) | 9.8 (6.5) | 9.5 (7.1) |

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, 10-item version; EQ-5D = EuroQol-5D; EQ VAS = EuroQol Visual Analog Scale; GH = Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) general health subscale; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire; PCS-36 = SF-36 physical component summary score; MCS-36 = SF-36 mental component summary score; PT/PP = pills taken/pills prescribed during the 7 days before data collection.

a Percentages exceed 100 because many participants had more than 1 condition.

Table 2.

Six-Week, 6-Month, and 1-Year Self-Efficacy and Primary and Secondary Outcome Scores by Study Group

| Outcome | Home (n=138) | Telephone (n=139) | Usual Care (n=138) |

| Intervention content delivery effectiveness | |||

| Self-efficacy score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 7.6 (1.5) | 7.2 (1.8) | 7.2 (1.9) |

| 6 Months | 7.5 (1.6) | 7.2 (1.8) | 7.2 (1.7) |

| 1 Year | 7.4 (1.6) | 7.3 (1.7) | 7.2 (1.8) |

| Primary outcome | |||

| PCS-36 score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 34.9 (11.9) | 36.3 (11.6) | 37.3 (11.1) |

| 6 Months | 36.2 (12.0) | 37.5 (11.8) | 37.2 (11.4) |

| 1 Year | 35.1 (12.2) | 36.4 (12.3) | 37.0 (11.6) |

| MCS-36 score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 51.6 (12.1) | 48.9 (12.3) | 48.6 (12.8) |

| 6 Months | 49.6 (13.7) | 46.1 (13.6) | 48.0 (13.0) |

| 1 Year | 51.2 (12.1) | 48.3 (12.0) | 48.5 (12.9) |

| Secondary outcome | |||

| GH score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 54.1 (21.4) | 54.4 (23.4) | 54.6 (25.0) |

| 6 Months | 53.8 (22.5) | 53.5 (23.5) | 54.4 (25.0) |

| 1 Year | 54.2 (23.1) | 54.3 (22.9) | 54.2 (24.1) |

| EQ-5D score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 0.80 (0.17) | 0.80 (0.17) | 0.80 (0.17) |

| 6 Months | 0.82 (0.16) | 0.81 (0.18) | 0.80 (0.20) |

| 1 Year | 0.79 (0.18) | 0.77 (0.20) | 0.81 (0.17) |

| EQ VAS score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 75.7 (18.5) | 73.5 (18.9) | 72.4 (19.7) |

| 6 Months | 74.6 (17.5) | 73.0 (20.4) | 72.9 (18.9) |

| 1 Year | 75.7 (15.2) | 72.3 (20.1) | 72.3 (18.9) |

| HAQ score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 0.89 (0.70) | 0.84 (0.71) | 0.76 (0.64) |

| 6 Months | 0.88 (0.67) | 0.85 (0.74) | 0.80 (0.68) |

| 1 Year | 0.91 (0.71) | 0.85 (0.71) | 0.77 (0.64) |

| CES-D score, mean (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 7.1 (6.0) | 7.6 (5.4) | 8.3 (6.5) |

| 6 Months | 7.5 (5.9) | 9.2 (6.5) | 8.2 (6.6) |

| 1 Year | 7.4 (6.3) | 8.6 (6.1) | 8.2 (6.9) |

| PT/PP, mean % (SD) | |||

| 6 Weeks | 93 (11) | 92 (15) | 93 (11) |

| 6 Months | 91 (16) | 89 (18) | 93 (13) |

| 1 Year | 94 (10) | 93 (12) | 91 (15) |

| Health care utilization at 1 year | |||

| Hospitalization, % | 16 (–) | 11 (–) | 15 (–) |

| Expenditures, $, mean (SD) | 14,105 (20,279) | 12,422 (14,241) | 11,493 (10,972) |

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, 10-item version; EQ-5D = EuroQol-5D; EQ VAS = EuroQol Visual Analog Scale; GH = SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) general health subscale; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire; MCS-36 = SF-36 mental component summary score; PCS-36 = SF-36 physical component summary score; PT/PP = pills taken/pills prescribed during the 7 days preceding data collection.

Illness Management Self-efficacy

The home group had significantly higher mean scores than the other groups at 6 weeks (effect size [change score/standard deviation] vs control = 0.27; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.10–0.43; P = .001; effect size vs telephone = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.05–0.38; P = .01). The significant differences persisted at 6 months, though with attenuation (effect size vs control = 0.17; 95% CI, 0.01–0.33; P = .04; effect size vs telephone = 0.17; 95% CI, 0.00–0.34; P = .05), but they were no longer present at 1 year.

Health Status

There were no significant differences among groups in PCS-36 or MCS-36 scores, the primary outcomes. At no point were the scores for either intervention group significantly higher than for the control group. Of secondary health status measures, there was a significant overall effect of the intervention on EQ VAS score (χ26 = 13.10; P = .04). Home group scores were higher than in the control group at 6 weeks (effect size = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.15–0.67; P = .002); 6 months (0.31; 95% CI, 0.05–0.57; P = .02), and 1 year (0.40; 95% CI, 0.14–0.66; P = .003), and higher than in the telephone group at 1 year (0.30; 95% CI, 0.03–0.56; P = .03). There were, however, no significant effects on the EQ-5D or GH subscale scores.

Other Outcomes

There were no significant differences between groups in HAQ scores (functional ability), CES-D scores (depressive symptoms), pills taken/pills prescribed ratios (medication adherence), hospitalizations, or total health care expenditures at any follow-up point.

Depressive Symptoms Moderator Analyses

The sample median CES-D score was 9. Among individuals with scores greater than 9 (moderate or greater symptoms), in-home HIOH was significantly more effective than usual care in improving PCS-36 scores at 6 months (3.1; 95% CI, 0.3–5.9; P = .03) and 1 year (3.0; 95% CI, 0.1–5.8; P = .04). Similar findings were noted for the EQ VAS at 6 weeks (effect size = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.12–1.03; P = .01) and 1 year (0.55; 95% CI, 0.09–1.01; P = .02). There was, however, no significant interaction between CES-D level, intervention group, and time in either analysis. There were no significant intervention effects on other outcomes for participants with CES-D scores above 9.

Intervention Characteristics

Peers’ written logs indicated 100% coverage of scripted topics for all 6 encounters in both intervention groups. The mean minutes per encounter was shorter for the telephone group (64.0 minutes, SD 11.9 minutes) than for the home group (73.5 minutes, SD 15.1 minutes), however. Mean ratings of the overall usefulness of HIOH were similarly favorable in both groups (home = 1.92 minutes, SD 0.97 minutes; telephone = 1.91 minutes, SD 0.82 minutes).

DISCUSSION

Ours was the first 1-year RCT of a face-to-face variant of the CDSMP, and only the second RCT of any variant of the program to utilize the robust MCS-36 and PCS-36 measures of overall mental and physical health status as predesignated primary outcomes.

We found a significant overall effect of in-home (but not telephone) HIOH on a secondary health status measure, the EQ VAS, at 1 year. There were, however, no significant effects of HIOH delivered in the home at any follow-up point on PCS-36 or MCS-36 scores, our primary outcomes, or other secondary outcomes, including hospitalizations and health care expenditures. Finally, there were no significant effects of HIOH delivered by telephone at any time. The single prior CDSMP study to use the PCS-36 and MCS-36 as primary outcome measures also found no significant effects.12

Other studies of the program instead found improvements in scores on the single-item Medical Outcomes Study health status assessment, and on energy/fatigue, social role/activities, and health distress subscales.5–11 Effects on these outcomes were not consistent among studies, however, and the only previous 1-year RCT of theCDSMP, involving an Internet variant, found a small effect on health distress, but no effects on health status, functional ability, or utilization at 1 year.10

Thus, we secondarily explored effects of HIOH on the SF-36 GH subscale, because it is similar to the health status measures employed in most prior RCTs of the CDSMP. Again, we found no effects. The inconsistent effects on these various health status measures among short term studies may reflect differences in study populations and/or program implementation. They may also reflect chance effects that were due to multiple outcomes testing, however, particularly as most studies did not predesignate primary outcomes. Given the lack of 1-year effects of HIOH on our other health status measures, the effect we found on EQ VAS could reflect its greater sensitivity39–43 or again could represent a chance finding.

Effects of the CDSMP on utilization have also been notably mixed, with a small reduction in hospitalizations at 4 to 6 months in a minority of studies.5,8 We found no effect of in-home HIOH deliver on hospitalizations at 1 year, as was the case in the prior Internet-based CDSMP RCT,10 and no effect on total expenditures at 1 year.

We did find a significant effect of in-home HIOH on illness management self-efficacy after the intervention, with an effect size comparable to that in earlier CDSMP studies. Thus, it is unlikely that the lack of effect of in-home HIOH on most outcomes stemmed from unsuccessful implementation of the intervention. The group format of the original CDSMP may provide benefits beyond one-on-one delivery, but such a hypothesis remains to be tested.

In summary, research suggests that peer-led chronic illness self-management programs result in small to moderate, short-term (4 to 6 month) effects on health outcomes, primarily subfacets of health status and possibly hospitalization, with no apparent effect on overall mental or physical health status or health care expenditures. A Cochrane review of RCTs of peer-led chronic illness self-management programs reached similar conclusions.53 One-year effects of the CDSMP and its variants thus far appear even more limited. Neither 1-year RCT involved the group-format CDSMP, however. Further evaluation of the effects of peer-group interaction afforded by the original CDSMP may be warranted.

These findings raise questions regarding the cost-effectiveness of such peer-led self-management programs as the CDSMP from the perspective of the health care system, particularly given the considerable resources required to offer and continuously monitor the fidelity of such interventions as HIOH and the original CDSMP. Studies to examine which elements of the multicomponent CDSMP most influence outcomes and to explore the usefulness of booster sessions may be helpful in achieving stronger and/or more sustained effects. The impact of the program might also be enhanced by identifying effect moderators—variables that specify for whom or under what conditions it works.54 We found modest yet persistent effects of HIOH on PCS-36 scores at 1 year among participants with a greater number of depressive symptoms. Adequately powered RCTs that stratify participants by depressive symptoms appear warranted to examine this issue further.

Although it is unclear why telephone HIOH had no effects, the absence of effect is consistent with the findings of a recent systematic review of telephone-based peer-support interventions.55 Face-to-face peer interaction may produce a more powerful therapeutic alliance than is possible by telephone.

Our study had some limitations. Most participants were white, female, married, and well-educated, so the extent to which our findings generalize to others is unclear. In studies of the CDSMP involving less well-educated minority participants, findings were similar to ours.7–9,11,13 It is also possible that many participants with the least favorable baseline status of the study outcome variables did not volunteer for this study. Nonetheless, the diseases, disease-related morbidity, and baseline status of outcome measures in our study sample were all highly similar to those in prior CDSMP studies. Finally, participant dropout was greater in the intervention groups, presumably reflecting the greater burden of their participation, a finding also observed in other studies of the program.

In conclusion, in a RCT of the one-on-one HIOH variant of the group format CDSMP, we found in-home (but not telephone) HIOH was effective in improving illness management self-efficacy for up to 6 months and scores on a secondary health status measure at 1 year. Neither intervention, however, had significant effects on either the primary outcomes of overall mental and physical health status at any interval or on other secondary study outcomes, including utilization. These findings challenge the suggestion, forwarded in several influential blueprints for health system redesign,1–3 that wider application of peer-led illness self-management programs would be cost-effective.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: Funded in part by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant number R01HS013603.

Trial Registration: Homing in on Health: Study of a Home Delivered Chronic Disease Self Management Program. http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov.Identifier NCT00263939.

REFERENCES

- 1.Improving Chronic Illness Care, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Chronic Care Model. http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=The_Chronic_Care_Model&s=2. Accessed Jun 21, 2008.

- 2.Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- 3.United Kingdom Department of Health. Saving lives, our healthier nation. http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/cm43/4386/4386.htm. Accessed Jun 21, 2008.

- 4.Stanford Patient Education Research Center. Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html. Accessed May 15, 2008.

- 5.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy A, Reeves D, Bower P, et al. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a national lay-led self care support programme for patients with long-term conditions: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(3):254–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, González VM. Hispanic chronic disease self-management: a randomized community-based outcome trial. Nurs Res. 2003;52(6):361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dongbo F, Fu H, McGowan P, et al. Implementation and quantitative evaluation of chronic disease self-management programme in Shanghai, China: randomized controlled trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(3):174–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerissen H, Belfrage J, Weeks A, et al. A randomised control trial of a self-management program for people with a chronic illness from Vietnamese, Chinese, Italian and Greek backgrounds. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K. Internet-based chronic disease self-management: a randomized trial. Med Care. 2006; 44(11):964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management programme for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(520):831–837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elzen H, Slaets JP, Snijders TA, Steverink N. Evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) among chronically ill older people in the Netherlands. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1832–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elzen H, Slaets JP, Snijders TA, Steverink N. The effect of a self-management intervention on health care utilization in a sample of chronically ill older patients in the Netherlands. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(1):159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(8):700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piette JD, Weinberger M, McPhee SJ. The effect of automated calls with telephone nurse follow-up on patient-centered outcomes of diabetes care: a randomized, controlled trial. Med Care. 2000;38(2): 218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piette JD, Weinberger M, McPhee SJ, Mah CA, Kraemer FB, Crapo LM. Do automated calls with nurse follow-up improve self-care and glycemic control among vulnerable patients with diabetes? Am J Med. 2000;108(1):20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiIorio C, Shafer PO, Letz R, Henry TR, Schomer DL, Yeager K; Project EASE Study Group. Behavioral, social, and affective factors associated with self-efficacy for self-management among people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9(1):158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilliam CM, Steffen AM. The relationship between caregiving self-efficacy and depressive symptoms in dementia family caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(2):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennard BD, Stewart SM, Hughes JL, Patel PG, Emslie GJ. Cognitions and depressive symptoms among ethnic minority adolescents. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006;12(3):578–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maly MR, Costigan PA, Olney SJ. Determinants of self efficacy for physical tasks in people with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(1):94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner JA, Ersek M, Kemp C. Self-efficacy for managing pain is associated with disability, depression, and pain coping among retirement community residents with chronic pain. J Pain. 2005;6(7):471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buszewicz M, Rait G, Griffin M, et al. Self management of arthritis in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen HQ, Carrieri-Kohlman V. Dyspnea self-management in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: moderating effects of depressed mood. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pariser D, O’Hanlon A. Effects of telephone intervention on arthritis self-efficacy, depression, pain, and fatigue in older adults with arthritis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2005;28(3):67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brody BL, Roch-Levecq AC, Gamst AC, Maclean K, Kaplan RM, Brown SI. Self-management of age-related macular degeneration and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(11):1477–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jerant AF, Kravitz RL, Moore-Hill MM, Franks P. Depressive symptoms moderated the effect of chronic illness self-management training on self-efficacy. Med Care. 2008;46(5):523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samsa G, Edelman D, Rothman ML, Williams GR, Lipscomb J, Matchar D. Determining clinically important differences in health status measures: a general approach with illustration to the Health Utilities Index Mark II. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15(2):141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(2):137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999; 159(15):1701–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, Gonzalez V, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome Measures For Health Education and Other Health Care Interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996.

- 33.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware JE Jr, Keller SD, Gandek B, Brazier JE, Sullivan M. Evaluating translations of health status questionnaires. Methods from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1995;11(3):525–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(4)(Suppl):AS264–AS279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.SF-36 health survey update. http://www.sf-36.org/tools/SF36.shtml. Accessed May 14, 2008.

- 37.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996; 37(1):53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson JA, Luo N, Shaw JW, Kind P, Coons SJ. Valuations of EQ-5D health states: are the United States and United Kingdom different? Med Care. 2005;43(3):221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Günther OH, Roick C, Angermeyer MC, König HH. The responsiveness of EQ-5D utility scores in patients with depression: A comparison with instruments measuring quality of life, psychopathology and social functioning. J Affect Disord. 2008;105(1–3):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu AW, Jacobson KL, Frick KD, et al. Validity and responsiveness of the euroqol as a measure of health-related quality of life in people enrolled in an AIDS clinical trial. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Dziedzic K, Dawes PT. Generic measures of health-related quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis: reliability, validity and responsiveness. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(12): 1380–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.König HH, Ulshöfer A, Gregor M, et al. Validation of the EuroQol questionnaire in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(11):1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krabbe PF, Peerenboom L, Langenhoff BS, Ruers TJ. Responsiveness of the generic EQ-5D summary measure compared to the disease-specific EORTC QLQ C-30. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(7):1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison T, Stuifbergen A. Disability, social support, and concern for children: depression in mothers with multiple sclerosis. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31(4):444–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huge V, Schloderer U, Steinberger M, et al. Impact of a functional restoration program on pain and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2006;7(6):501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kilbourne AM, Justice AC, Rollman BL, et al. Clinical importance of HIV and depressive symptoms among veterans with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(7):512–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(8):1417–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jerant AF, DiMatteo R, Arnsten J, Moore-Hill M, Franks P. Self-report adherence measures in chronic illness: retest reliability and predictive validity. Med Care. 2008;46(11):1134–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/home/medicare.asp. Accessed Jun 12, 2008. [PubMed]

- 50.Tumeh JW, Moore SG, Shapiro R, Flowers CR. Practical approach for using Medicare data to estimate costs for cost-effectiveness analysis. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2005;5(2):153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Red Book 2008. 112th ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Thomson Healthcare; 2008.

- 52.Burton P, Gurrin L, Sly P. Extending the simple linear regression model to account for correlated responses: an introduction to generalized estimating equations and multi-level mixed modelling. Stat Med. 1998;17(11):1261–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foster G, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SE, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4): CD005108. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dale J, Caramlau IO, Lindenmeyer A, Williams SM. Peer support telephone calls for improving health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD006903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]