Abstract

Background/Aims

Chronic hepatitis B has a high prevalence (>8%) in China. We compared the safety and efficacy of entecavir with that of lamivudine for the treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B in China.

Methods

A total of 519 nucleoside-naive Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B were randomized (1:1) and treated with entecavir 0.5 mg/d or lamivudine 100 mg/d. The primary endpoint was serum HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay and alanine aminotransferase <1.25 × upper limit of normal (ULN) at week 48. Patients with missing week 48 measurements were considered non-responders.

Results

About 90% (231/258) of entecavir-treated versus 67% (174/261) of lamivudine-treated patients achieved the primary endpoint (P < 0.0001). The mean reduction from baseline in HBV DNA was greater with entecavir than lamivudine (5.90 vs. 4.33 log10 copies/ml, P < 0.0001). Greater proportions of entecavir-treated patients achieved undetectable HBV DNA (<300 copies/ml) by polymerase chain reaction assay (76% vs. 43%, P < 0.0001) and alanine aminotransferase normalization (≤1 × ULN, 90% vs. 78%, P = 0.0003). Entecavir and lamivudine achieved comparable rates of HBeAg seroconversion (15% and 18%, respectively). Safety was comparable between the two treatments.

Conclusions

For nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B, entecavir achieves superior virological and biochemical benefit over lamivudine, with a comparable safety profile.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, China, Clinical trial, Efficacy, Superiority, Safety, Tolerability

Introduction

Approximately 400 million people worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) [1]. Of these, 275 million (67%) live in the Asia-Pacific region, including approximately 170 million people in China, where the disease is endemic [1, 2]. Persons with chronic hepatitis B are at a high risk of developing liver failure, hepatic cirrhosis, and primary hepatocellular carcinoma [3]. The goal of treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B is to eliminate or permanently suppress HBV replication, the initiating factor for liver disease. A recent study has shown that antiviral therapy with lamivudine can reduce liver complications and slow disease progression in patients with chronic HBV and advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis [4]. However, prolonged treatment with lamivudine is associated with the emergence of YMDD mutations, with up to 70% of patients developing resistance to lamivudine after 4 years of treatment [5].

Chronic hepatitis B is a treatable disease. Currently available therapeutic options include oral antiviral agents (lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil, and entecavir) and parenteral interferon-α (standard and pegylated). Entecavir, a guanosine analog, is a potent and selective inhibitor of HBV DNA polymerase [6, 7]. In vitro studies demonstrate that entecavir has a low EC50 (4 nM) for wild-type virus, and that entecavir is >300-fold more potent against wild-type virus than other antiviral agents that are either approved or under development (e.g., lamivudine, adefovir, telbivudine, or tenofovir) [7]. The selection of the 0.5 mg dose of entecavir for evaluation in phase III studies in nucleoside-naïve patients resulted from phase II dose-ranging studies conducted multinationally and in China [8, 9]. The results of two large, multinational phase III studies conducted outside of mainland China in nucleoside-naïve HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients have recently been reported and demonstrated that the rates of histologic, virologic, and biochemical improvement after 48 weeks of treatment were significantly higher with entecavir than with lamivudine [10, 11]. The phase III study presented here was designed to compare the efficacy and safety of entecavir 0.5 mg once daily to lamivudine in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B who had not previously been treated with a nucleoside analog.

Patients and methods

Patients

Eligible patients were at least 16 years of age and had a documented history of chronic HBV infection (hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg]-positive for ≥6 months) and compensated liver disease (total bilirubin ≤2.5 mg/dl, international normalized ratio ≤1.5, albumin ≥3.0 g/dl, and no current evidence or history of variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, or ascites requiring diuretics or paracentesis). Eligible patients also had a serum HBV DNA level ≥3.0 MEq/ml by branched-chain DNA (bDNA) assay at screening and evidence of HBV DNA by any commercial assay ≥12 weeks prior to screening, and had serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels 1.3–10 × the upper limit of normal (ULN) at screening and at least once ≥12 weeks prior to screening. Patients with either hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive or HBeAg-negative/hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb)-positive disease were eligible.

Exclusion criteria included the following: co-infection with hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, or human immunodeficiency virus; other forms of liver disease; more than 12 weeks of therapy with a nucleoside or nucleotide analog with activity against HBV; and therapy with any anti-HBV drug within 24 weeks prior to randomization. During the study patients were not allowed to use traditional Chinese medicines and other herbal medicines intended to improve or protect liver function, or improve or prevent fibrosis.

Study design and outcome measures

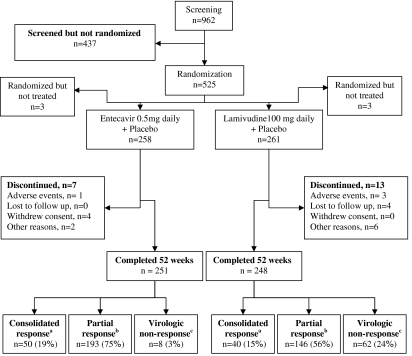

This randomized (1:1), double-blind, controlled study was conducted at 26 sites in China. The study compared oral entecavir 0.5 mg once daily (Baraclude, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wallingford, CT, U.S.A.) to oral lamivudine 100 mg once daily (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, UK) for up to 96 weeks in patients with chronic hepatitis B (Fig. 1). Randomization was performed centrally and stratified by HBeAg status and investigative site. Response to therapy was initially assessed at week 52, based on results obtained at week 48. Patients were seen for scheduled visits at baseline (day 1), weeks 2 and 4, and every 4 weeks for the first year of treatment. HBV DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was determined at baseline and at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 48 during the first year.

Fig. 1.

Study design and patient disposition. a—Consolidated response: HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay and HBeAg-negative for at least 24 weeks (weeks 24–48) and ALT <1.25 × ULN at week 48. Patients discontinued study drug and were followed up for 24 weeks off-treatment; b—Partial response: HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay but not yet meeting the criteria for a Consolidated response. Patients continued blinded treatment in the second year of the study. c—Virologic nonresponse: HBV DNA ≥0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA. Patients were to discontinue study drug at week 52 and could either enroll in an entecavir rollover study or be followed in the present study for 24 weeks post-dosing

A clinical trial permit was granted by the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA) to conduct the study. All 26 medical centers participating in the study were certified by the SFDA as clinical trial sites. The study protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board and local ethics committee of each of the participating medical centers. All patients gave written informed consent before any study-related procedures were performed.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients at week 48 who achieved the composite endpoint of HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay (Bayer Quantiplex HBV DNA Version 1.0, Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, NY, USA; limit of quantitation = 0.7 MEq/ml) and ALT <1.25 × ULN. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the mean reduction from baseline in HBV DNA by PCR assay (Roche Cobas Amplicor HBV Monitor version 2, LOQ = 300 copies/ml) at week 48; and the proportions of patients who achieved each of the following endpoints at week 48: HBV DNA <300 copies/ml (by PCR assay), HBeAg loss, HBeAg seroconversion (HBeAg loss/HBeAb gain), and ALT normalization (ALT ≤1 × ULN).

HBeAg-positive patients achieved a consolidated response at week 48 by having HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay and being HBeAg-negative for at least 24 weeks (i.e., week 24 through week 48) plus having ALT <1.25 × ULN at week 48. HBeAg-negative patients achieved a consolidated response by having HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA for at least 24 weeks and ALT <1.25 × ULN at week 48. Patients achieving a consolidated response at week 48 discontinued study drug at week 52 and were followed for 24 weeks off-treatment. Efficacy analyses also evaluated the proportions of these patients who had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml by PCR, ALT normalization, and HBe seroconversion (for patients who were HBeAg-positive at baseline) at the time of discontinuing study drug and sustained responses 24 weeks off-treatment. Patients who achieved a partial response at week 48 (HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay but not yet meeting criteria for a consolidated response) were eligible to continue blinded treatment in the second year of the study. Virologic non-responders at week 48 (HBV DNA ≥0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA) were to discontinue study drug at week 52 and could either enroll in an entecavir rollover study or be followed for 24 weeks post-dosing and begin marketed anti-HBV therapy as recommended by their physician.

Safety information was obtained from all patients who received at least one dose of study medication. Safety endpoints included adverse events, laboratory abnormalities, and discontinuation of study medication owing to adverse events or laboratory abnormalities. The proportion of patients who experienced an ALT flare (defined as an on-treatment ALT measurement >2 × baseline and >10 × ULN) was also assessed.

Statistical analysis

The target sample size of 225 patients per treatment group provided 90% power to demonstrate superiority of entecavir over lamivudine for the primary efficacy endpoint. Analyses of efficacy endpoints focused on treated patients and were based on the intent-to-treat data set. In the principal analysis of binary endpoints, patients with a missing week 48 measurement for an endpoint were treated as having non-response for that endpoint. Treatment comparisons for binary variables were stratified by baseline HBeAg status with Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel weights. Confidence intervals for difference estimates were based on the normal approximation to the binomial distribution. Comparisons of continuous variables used t-tests based on linear regression models with covariates for baseline measurement, baseline HBeAg status (positive or negative), and treatment group. P values were based on two-sided tests.

Results

Study population

Of the 962 patients enrolled and screened, 525 met the criteria and were randomized (entecavir 261, lamivudine 264), and 519 received at least one dose of study drug (entecavir 258, lamivudine 261). The two treatment groups were well balanced at baseline for demographic and disease characteristics (Table 1). Most patients were male (82%) and all were Asian; the mean age was 30 years. Eighty-six percent of patients were HBeAg-positive and, as expected, mean HBV DNA was higher for these patients than for HBeAg-negative patients. Fifteen percent of patients had been previously treated with interferon-α. Most patients completed 52 weeks of dosing (entecavir, 96%; lamivudine, 94%). An overview of the study design and patient flow is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | Entecavir 0.5 mg (n = 258) | Lamivudine 100 mg (n = 261) |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 211 (82) | 217 (83) |

| Age, years; mean (SD) | 30 (9) | 30 (9) |

| HBeAg(+), n (%) | 225 (87) | 221 (85) |

| HBV DNA by PCR assay, log10 copies/ml; mean (SD) | ||

| Total population | 8.64 (0.99) | 8.48 (1.12) |

| HBeAg(+) population | 8.77 (0.86) | 8.65 (1.0) |

| HBeAg(−) population | 7.70 (1.28) | 7.59 (1.33) |

| ALT, U/L; mean (SD) | ||

| Total population | 196 (140) | 198 (180) |

| HBeAg(+) population | 191 (135) | 204 (192) |

| HBeAg(–) population | 225 (169) | 164 (83) |

| Prior interferon-α treatment, n (%) | 37 (14) | 42 (16) |

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; SD, standard deviation; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen

Treatment efficacy

Entecavir was superior to lamivudine for the proportion of patients in each treatment arm achieving the primary endpoint (HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay and ALT <1.25 × ULN) at week 48 (90% vs. 67%, P < 0.0001; Table 2). For this composite endpoint, results consistently favored entecavir over lamivudine within baseline subgroups (HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative status; HBV DNA <3 log10 or ≥3 log10 MEq/ml by bDNA assay; ALT <2.6 × ULN or ≥2.6 × ULN; interferon-naïve or interferon-pretreated; and male or female). Among entecavir-treated patients, a higher proportion of HBeAg-negative patients versus HBeAg-positive patients achieved the primary endpoint (97% vs. 88%, respectively). No differences were observed among HBV DNA and ALT subgroup responses.

Table 2.

Virological, biochemical and serologic endpoints at week 48a

| Endpoint | Entecavir 0.5 mg | Lamivudine 100 mg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBeAg(+) population (n = 225) | HBeAg(−) population (n = 33) | Total population (n = 258) | HBeAg(+) population (n = 221) | HBeAg(−) population (n = 40) | Total population (n = 261) | P valueb | |

| Composite endpoint (HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by bDNA assay and ALT <1.25 × ULN) | 119 (88%) | 32 (97%) | 231 (90%) | 143 (65%) | 31 (78%) | 174 (67%) | <0.0001 |

| HBV DNA by PCR assay | |||||||

| Mean (SE) change from baseline at week 48, log10 copies/ml | −6.00 (0.072) | −5.22 (0.230) | −5.90 (0.071) | −4.30 (0.134) | −4.50 (0.282) | −4.33 (0.122) | <0.0001 |

| HBV DNA <300 copies/ml at week 48 | 116 (74%) | 31 (94%) | 197 (76%) | 83 (38%) | 29 (73%) | 112 (43%) | <0.0001 |

| ALT normalization (ALT ≤1 × ULN) | 200 (89%) | 31 (94%) | 231 (90%) | 172 (78%) | 31 (78%) | 203 (78%) | 0.0003 |

| HBeAg loss and seroconversion (acquisition of antibodies to HBeAg) | |||||||

| HBeAg loss, No./No. HBeAg(+) at baseline | 41 (18%) | NA | 41/225 (18%) | 44 (20%) | NA | 44/221 (20%) | NS |

| HBeAg seroconversion, No./No. HBeAg(+) at baseline | 33 (15%) | NA | 33/225 (15%) | 39 (18%) | NA | 39/221 (18%) | NS |

aFor all analyses with the exception of mean reduction in HBV DNA by PCR assay, patients with a missing value for an endpoint were considered nonresponders for that endpoint

bP value refers to the significance of the differences between the total populations except for serology, which is between HBeAg(+) populations in each treatment arm

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SE, standard error; NS, not significant; ULN, upper limit of normal

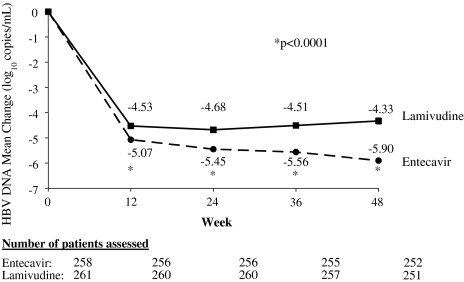

Patients treated with entecavir demonstrated a rapid reduction in HBV DNA levels; the mean reduction in HBV DNA at week 12 (the first on-treatment visit with HBV DNA measurements) was significantly greater for the entecavir group (−5.07 log10 copies/ml) than for the lamivudine group (−4.53 log10 copies/ml; P < 0.0001). Mean reduction in HBV DNA was also greater for entecavir-treated patients at weeks 24, 36, and 48, when the mean reduction was −5.90 log10 copies/ml for entecavir-treated patients versus −4.33 log10 copies/ml for lamivudine-treated patients (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2). Mean HBV DNA reduction was greater in entecavir- versus lamivudine-treated patients within baseline subgroups (HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative status; HBV DNA <3 log10 or ≥3 log10 MEq/ml by bDNA assay; ALT <2.6 × ULN or ≥2.6 × ULN). Among entecavir-treated patients, a greater HBV DNA reduction was observed in the high-baseline HBV DNA subgroup (>3 log10 MEq) and the HBeAg-positive subgroup.

Fig. 2.

Change from baseline in HBV DNA by PCR assay through week 48

Significantly greater proportions of entecavir- than lamivudine-treated patients achieved the secondary endpoints of HBV DNA <300 copies/ml by PCR assay at 48 weeks (76% vs. 43%, P < 0.0001; Table 2) and ALT normalization by week 48 (90% vs. 78%, P = 0.0003; Table 2). Subgroup analysis on the proportion of patients achieving HBV DNA <300 copies/ml showed that entecavir was consistently better than lamivudine for each subgroup. Among entecavir-treated patients, subgroup analysis also showed that higher proportions of HBeAg-negative patients, patients with lower baseline viral load (<3 log10 MEq/ml by bDNA), patients with baseline ALT ≥2.6 × ULN, and interferon-naïve patients achieved HBV DNA reductions of <300 copies/ml by PCR. There was no difference between subgroups for ALT normalization.

Among patients who were HBeAg-positive at baseline, entecavir was comparable to lamivudine for proportions of patients who achieved loss of HBeAg (entecavir: 18%; lamivudine: 20%) and HBeAg seroconversion (entecavir: 15%; lamivudine: 18%) at week 48 (P = NS for both comparisons).

Nineteen percent of entecavir-treated patients and 15% of lamivudine-treated patients achieved a consolidated response at week 48. A higher proportion of patients achieved a consolidated response in the baseline HBeAg-negative subgroup (entecavir 76%, lamivudine 60%) than in the baseline HBeAg-positive subgroup (entecavir 11%, lamivudine 7%). More patients in the entecavir group than the lamivudine group achieved a partial response at week 48 (entecavir 75%, lamivudine, 56%) and were therefore eligible to continue to a second year of blinded dosing. Virologic non-response occurred in fewer patients treated with entecavir (3%) than with lamivudine (24%).

Off-treatment efficacy

About 50 entecavir- and 40 lamivudine-treated patients achieved a consolidated response at week 48, discontinued study drug at week 52, and were followed for 24 weeks off-treatment. Of these entecavir-treated patients, 49 had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml, 46 had ALT <1 × ULN, and 19 achieved HBe seroconversion (among patients who were HBeAg-positive at baseline) at week 48. These responses were sustained for 24 weeks off-treatment in 20%, 83%, and 68% of patients, respectively. Among lamivudine-treated patients with a consolidated response at week 48, 35 had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml; 39 had ALT <1 × ULN; and 13 had achieved HBeAg seroconversion (among patients who were HBeAg-positive at baseline). By the end of the 24-week follow-up period, these responses were sustained in 20%, 56%, and 69% of patients, respectively.

Adverse events

During the first year of dosing, the mean exposure to study therapy was 51.1 weeks for the entecavir group and 50.5 weeks for the lamivudine group. The proportion of patients experiencing at least one adverse event, irrespective of severity or relationship to study drug, was comparable between the two treatment groups (entecavir 60%; lamivudine 56%). The most frequently occurring on-treatment adverse events were nasopharyngitis, increased ALT, upper respiratory tract infection, fatigue, upper-abdominal pain, and diarrhea (Table 3). The number of serious adverse events was also comparable between the two treatment groups (entecavir, 9 [3%] patients; lamivudine, 12 [5%] patients). Few patients discontinued blinded treatment due to adverse events during the first year of dosing (entecavir, 1 patient; lamivudine, three patients). There were no deaths or malignant neoplasms reported.

Table 3.

Summary of safety during first year of dosing

| Entecavir 0.5 mg (n = 258) | Lamivudine 100 mg (n = 261) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 154 (60%) | 145 (56%) |

| Most frequent adverse eventsa | ||

| Nasopharyngitis | 52 (20%) | 35 (13%) |

| ALT increased | 17 (7%) | 23 (9%) |

| Upper-respiratory-tract infection | 15 (6%) | 10 (4%) |

| Fatigue | 13 (5%) | 27 (10%) |

| Upper-abdominal pain | 13 (5%) | 15 (6%) |

| Diarrhoea | 13 (5%) | 4 (2%) |

| ALT flareb | 11 (4%) | 15 (6%) |

| Grade 3–4 adverse events | 18 (7%) | 19 (7%) |

| Serious adverse events | 9 (3%) | 12 (5%) |

| Discontinuations due to adverse events | 1 (<1%) | 3 (1%) |

aAdverse events occurring in ≥5% of patients in either treatment group

bALT flare was defined as an on-treatment ALT measurement >2 × baseline and >10 × ULN

There were no notable differences in the type or frequency of laboratory abnormalities on treatment between the two groups. The proportion of patients with hematologic abnormalities was low and comparable. Most patients had normal renal function tests at baseline and on treatment. Elevations in serum amylase occurred in 26% of patients receiving entecavir and 29% of patients receiving lamivudine, but no patients were reported to have a diagnosis of clinical pancreatitis.

ALT flares occurred in 11 (4%) patients receiving entecavir and in 15 (6%) patients receiving lamivudine. In the entecavir group, ALT flares in all 11 patients occurred temporally in the setting of at least a 2 log10 reduction in HBV DNA, and all flares resolved during continued entecavir treatment. None of the entecavir-treated patients who experienced ALT flares had concurrent abnormalities of total bilirubin levels, serum albumin levels, or INR and none of the patients experienced hepatic decompensation. In the lamivudine group, 9 of the 15 patients had ALT flares occurring in the setting of at least a 2 log10 reduction in HBV DNA; four patients had ALT flares associated with increasing or persistently elevated HBV DNA levels; one patient had two ALT flares (the first ALT flare associated with at least a 2 log10 reduction in HBV DNA, and the second associated with increasing HBV DNA levels); and one patient had an ALT flare within 3 weeks of initiating lamivudine, discontinued, and had no HBV DNA levels obtained on treatment. The ALT flares had resolved when lamivudine was continued for 9 patients, resolved after discontinuation of lamivudine for 1 patient, and were ongoing at the time of data cut-off in 2 patients (both patients were virologic non-responders and rolled over into entecavir rollover study at week 52). Of the lamivudine-treated patients who experienced ALT flares, 1 patient had a concurrent increase in the INR and 2 patients had concurrent increases in total bilirubin levels.

Discussion

After 48 weeks of treatment, entecavir was superior to lamivudine across all primary and secondary virological and biochemical endpoints. Entecavir was also significantly better than lamivudine in reaching the composite endpoint, 90% vs. 67% (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, entecavir produced a mean reduction in serum HBV DNA from baseline after 48 weeks of treatment that was approximately 1.5 log10 copies/ml (>30-fold) greater than lamivudine. Serum ALT levels, which serve as a marker for hepatic inflammation in chronic hepatitis B patients, normalized in a significantly greater proportion of patients receiving entecavir compared to those receiving lamivudine.

The findings of this study are in agreement with 2 multinational studies [10, 11]. In HBeAg-positive patients entecavir showed superiority over lamivudine for HBV DNA <300 (67% vs. 37%), ALT <1 × ULN (68% vs. 60%), and HBeAg seroconversion (21% vs. 18%). In HBeAg-positive patients, entecavir showed superiority over lamivudine for HBV DNA <300 (90% vs. 72%) and ALT normalization (78% vs. 71%). In addition, these studies also looked at histologic improvement as a primary endpoint, the results of which were 72% vs. 62% for HBeAg-positive patients and 70% vs. 61% for HBeAg-negative patients for entecavir- and lamivudine-treated patients respectively [10, 11].

The results of subgroup analysis (HBeAg-positive and -negative; baseline HBV DNA <3.0 log10 MEq copies/ml and baseline HBV DNA ≥3.0 log10 MEq/ml; baseline ALT <2.6 × ULN and baseline ALT ≥2.6 × ULN; prior interferon treatment and interferon-naïve subgroups) consistently favored entecavir over lamivudine for all evaluated endpoints. Results also showed that entecavir was effective for all virologic and biochemical endpoints in the majority of patients, irrespective of subgroup.

The design of this study included a 24-week off-treatment follow-up of patients who had achieved a consolidated response by week 48 in order to assess whether the cessation of treatment for patients who had responded well to therapy could be part of future therapeutic strategies. Although more entecavir- than lamivudine-treated patients achieved a consolidated response at week 48, the proportion of patients in each treatment arm who sustained virologic, biochemical, and serological responses after 24 weeks of off-treatment were comparable, with approximately 70% of patients in both treatment arms sustaining HBeAg seroconversion.

The presence and elevation of HBV DNA are risk factors for development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in persons with chronic hepatitis B [13, 14]. Recently updated treatment guidelines recognize these risks by establishing suppression of HBV replication as the primary goal of therapy [12, 15, 16]. Treatment with entecavir produced rapid and profound reductions in HBV DNA levels in this study. As early as the first HBV DNA assessment after 12 weeks of treatment, the mean reduction in HBV DNA was significantly greater for the entecavir group (5.07 log10 copies/ml) than for the lamivudine group (4.53 log10 copies/ml; P < 0.0001). Moreover, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with entecavir had undetectable HBV DNA levels by PCR assay after 48 weeks of treatment compared to lamivudine (76% vs. 43%). The marked suppression in HBV DNA levels produced by entecavir compares favorably to that reported in nucleoside-naïve patients treated with adefovir. One year of treatment with adefovir dipivoxyl 10 mg daily has been shown to suppress HBV DNA levels to undetectable levels (<400 copies/ml) in 21% of nucleoside-naïve, HBeAg-positive patients and 51% of nucleoside-naïve, HBeAg-negative patients [17, 18].

In this study, entecavir was found to be safe and well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to that of lamivudine. ALT flares during entecavir treatment were infrequent, were temporally associated with reductions in HBV DNA levels, and resolved with continued entecavir therapy. Further monitoring will be important to confirm the long-term safety of entecavir.

The findings of the present study are encouraging because they demonstrate the superior efficacy of entecavir compared to lamivudine in nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B, with comparable safety and tolerability. They are in agreement with the findings of multinational studies in which entecavir consistently demonstrated superior virological and biochemical responses in patients with HBeAg-positive or -negative chronic hepatitis B [10, 11]. On the basis of these findings, entecavir shows considerable promise for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- bDNA

branched-chain DNA

- HBeAg

hepatitis B e antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ULN

upper limit of normal

Footnotes

Other members of the study group

In addition to the authors, the AI463023 Study Group included the following investigators: Shuqing Cai, Weixiong Chen, Yagang Chen, Jinlin Hou, Darong Hu, Yanyan Ji, Jidong Jia, Lin Lin, Aimin Sun, Deying Tian, Mobin Wan, Qinhuan Wang, Lai Wei, Weimin Xu, Youkuan Yin, Minde Zeng, Lingxia Zhang, Shuncai Zhang, Xiaqiu Zhou, Limin Zhu.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12072-007-9043-0.

References

- 1.Hepatitis B Foundation [Web site]. Available at: http://www.hepb.org/02-0360.hepb. Accessed January 19, 2005.

- 2.Sun Z, Ming L, Zhu X, Lu J. Prevention and control of hepatitis B in China. J Med Virol 2002;67:447–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1733–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Liaw YF, Sung JJY, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1521–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NWY, Atkins M, Hunt C, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:687–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Colonno RJ, Genovesi EV, Medina I, Lamb L, Durham SK, Huang ML, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment results in sustained antiviral efficacy and prolonged life span in the woodchuck model of chronic hepatitis infection. J Infect Dis 2001;184:1236–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Innaimo SF, Seifer M, Bisacchi GS, Standring DN, Zahler R, Colonno RJ. Identification of BMS-200475 as a potent and selective inhibitor of hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997;41:1444–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lai C-L, Rosmawati M, Lao J, Van Vlierberghe H, Anderson FH, Thomas N, et al. Entecavir is superior to lamivudine in reducing hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1831–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Yao GB, Xu DZ, Wang BE, Zhou X-Q, Lei B-J, Zhang DF, et al. A phase II study in China of the safety and antiviral activity of entecavir in adults with chronic hepatitis B infection. Hepatology 2003;38(suppl 1):711A. [DOI]

- 10.Chang T-T, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao Y-C, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1001–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Lai C-L, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang T-T, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, et al. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1011–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lok ASF, McMohan BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2007;45:507–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Iloeje UH, Yang H-I, Su J, Jen C-L, You S-L, Chen C-J. Predicting cirrhosis risk based upon the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology 2006;130:678–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chen C-J, Yang H-I, Su J, Jen C-L, You S-L, Lu S-N, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 2006;295:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Liaw YF, Leung N, Guan R, Lau GKK, Merican I, McCaughan G, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatiitis B: a 2005 update. Liver Int 2005;25:472–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han S-HB, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;8:936–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Marcellin P, Chang T-T, Lim SG, Tong MJ, Sievert W, Shiffman ML, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2003;348:808–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang T-T, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2003;348:800–7. [DOI] [PubMed]