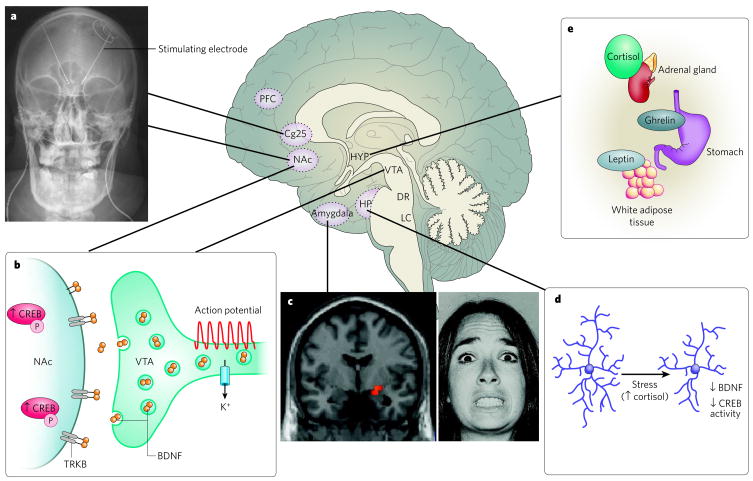

Figure 1. Neural circuitry of depression.

Several brain regions are implicated in the pathophysiology of depression. a, Deep brain stimulation of the subgenual cingulate cortex (Cg25)17 or the nucleus accumbens (NAc)18 has an antidepressant effect on individuals who have treatment-resistant depression. This effect is thought to be mediated through inhibiting the activity of these regions either by depolarization blockade or by stimulation of passing axonal fibres. (Image courtesy of T. Schlaepfer and V. Sturm, University Hospital, Bonn, Germany.) b, Increased activity-dependent release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) within the mesolimbic dopamine circuit (dopamine-producing ventral tegmental area (VTA) to dopamine-sensitive NAc) mediates susceptibility to social stress25, probably occurring in part through activation of the transcription factor CREB (cyclic-AMP-response-element-binding protein)20 by phosphorylation (P). c, Neuroimaging studies strongly implicate the amygdala (red pixels show activated areas) as an important limbic node for processing emotionally salient stimuli, such as fearful faces7. (Image courtesy of D. Weinberger, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland). d, Stress decreases the concentrations of neurotrophins (such as BDNF), the extent of neurogenesis and the complexity of neuronal processes in the hippocampus (HP), effects that are mediated in part through increased cortisol concentrations and decreased CREB activity 2,14. e, Peripherally released metabolic hormones in addition to cortisol, such as ghrelin95 and leptin96, produce mood-related changes through their effects on the hypothalamus (HYP) and several limbic regions (for example, the hippocampus, VTA and NAc). DR, dorsal raphe; LC, locus coeruleus; PFC, prefrontal cortex.