Abstract

Expression of human tau in Caenorhabditis elegans neurons causes accumulation of aggregated tau leading to neurodegeneration and uncoordinated movement. We used this model of human tauopathy disorders to screen for genes required for tau neurotoxicity. Recessive loss-of-function mutations in the sut-2 locus suppress the Unc phenotype, tau aggregation and neurodegenerative changes caused by human tau. We cloned the sut-2 gene and found it encodes a novel sub-type of CCCH zinc finger protein conserved across animal phyla. SUT-2 shares significant identity with the mammalian SUT-2 (MSUT-2). To identify SUT-2 interacting proteins, we conducted a yeast two hybrid screen and found SUT-2 binds to ZYG-12, the sole C. elegans HOOK protein family member. Likewise, SUT-2 binds ZYG-12 in in vitro protein binding assays. Furthermore, loss of ZYG-12 leads to a marked upregulation of SUT-2 protein supporting the connection between SUT-2 and ZYG-12. The human genome encodes three homologs of ZYG-12: HOOK1, HOOK2 and HOOK3. Of these, the human ortholog of SUT-2 (MSUT-2) binds only to HOOK2 suggesting the interaction between SUT-2 and HOOK family proteins is conserved across animal phyla. The identification of sut-2 as a gene required for tau neurotoxicity in C. elegans may suggest new neuroprotective strategies capable of arresting tau pathogenesis in tauopathy disorders.

INTRODUCTION

In several aging associated neurodegenerative diseases, tau aggregates into abnormal filaments forming neurofibrillary and glial tangles (1,2). These disorders, collectively called tauopathies, include Alzheimer's disease, Down syndrome, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick's disease, Guam amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/Parkinson's dementia complex and frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism chromosome 17 type (FTDP-17) (1,3). In FTDP-17, autosomal dominant mutations in the gene encoding tau (MAPT) cause the disorder (4–6). Therefore, abnormal tau can be pathogenic rather than merely serving as a marker for neurodegeneration. How mutated or normal tau produces the constellation of phenotypes seen in tauopathy disorders remains unclear. One hypothesis suggests tau aggregates are intrinsically toxic and kill neurons directly. In this case, tau mutations would cause disease by promoting tau self-aggregation. Mechanisms of mutation-driven tau aggregation may involve reducing the affinity of tau for microtubules (MTs) resulting in an increase in free tau concentrations (7) and accelerating the rate of tau self-aggregation (8,9) and/or preventing the degradation of abnormal tau (10).

Aggregated protein deposits are observed in numerous neurodegenerative diseases, and in some cases more than one type of deposit is seen in a single disease. For many of these protein aggregates, rare mutations in the gene encoding the deposited protein cause neurodegeneration (11–14). In at least some cases, these mutations increase in vitro aggregation rates. This is true for some FTDP-17 MAPT mutations that accelerate tau aggregation, as well as at least one amyloid precursor protein mutation that accelerates Aβ aggregation. These findings indicate that aggregation is a critical part of pathogenesis and that the aggregated protein itself may be the toxic entity that disrupts cellular function. Whether the toxic entity is a dimer, protofibril or mature aggregated mass remains to be resolved. However, the recurring theme of aggregating abnormal proteins in neurodegenerative disease suggests that protein degradation pathways responsible for preventing protein aggregation fail in a number of these disorders.

We developed a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans model of human tauopathy diseases by expressing human tau in worm neurons (15) to explore pathways that contribute to tau-induced neurodegeneration. Expression of mutated human tau causes uncoordinated locomotion (Unc), a phenotype characteristic of a variety of C. elegans nervous system defects. Tau expression in worm neurons produces several hallmarks of human tauopathies including the accumulation of detergent insoluble phosphorylated tau protein and neurodegeneration. To identify genes that control tau neurotoxicity, we carried out a forward genetic screen for mutations that prevent the tau-induced Unc phenotype. We previously described a gene whose loss-of-function suppresses the tau-induced Unc phenotype and called this mutated gene suppressor of tau 1 (sut-1). Animals carrying a loss-of-function mutation in sut-1 are resistant to the toxic effects of tau indicating that the SUT-1 protein is essential for tau neurotoxicity in C. elegans. In this report, we describe a different well-conserved gene named sut-2 that when mutated prevents tau neurotoxicity. The identification of SUT-2 as a participant in tau-induced neurotoxicity suggests novel potential neuroprotective strategies for the treatment of tauopathy disorders.

RESULTS

We used the transgenic C. elegans tauopathy model previously described (15). In this model, mutated human tau protein is expressed in all neurons causing neuronal dysfunction, accumulation of insoluble tau and neurodegeneration leading to an Unc phenotype. The C. elegans protein closest to human tau is the protein with tau-like repeats-1 (ptl-1). In adult worms, PTL-1 is only expressed in six touch neurons, but is not required for normal mechanosensory function of these neurons (16,17) or normal motor function (unpublished findings). This suggests normal ptl-1 does not impact the tauopathy phenotype in this model.

To identify genes required for this Unc phenotype, we mutagenized Unc strain T337 (expressing mutant human tau carrying the FTDP-17 V337M mutation) and screened for mutant worm lines with normal (non-Unc) locomotion. We identified two mutant alleles, bk87 and bk741, which partially suppress the tauopathy phenotype. When either is present in the homozygous state in the parental T337 line, motility is restored to near wild-type levels (Fig. 1). Here, we describe the characterization of the bk87 and bk741 mutant strains. In these lines, the tau transgene was not altered by mutagenesis because out-crossed mutant lines had Unc progeny similar to those of the T337 parental strain.

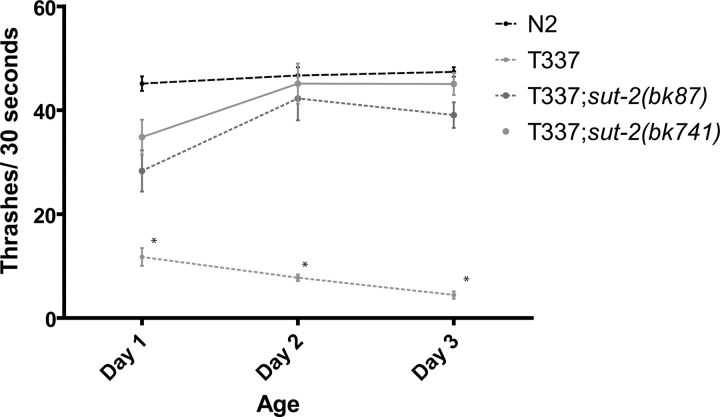

Figure 1.

Loss of sut-2 suppresses tau-induced locomotion defects. Liquid thrashing assays for staged 1- to 3-day-old worms. N2 is wild-type. T337 is tau transgenic. T337;sut-2(bk87) and T337;sut-2(bk741) are tau suppressor strains. Each data point is the mean (±SEM) thrashing rate for 15 worms. Statistical comparison was made using one-way ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) with Dunn's post hoc comparison. Asterisks denote that T337 animals are significantly different (P < 0.0001) from N2, T337;sut-2(bk87) and T337;sut-2(bk741).

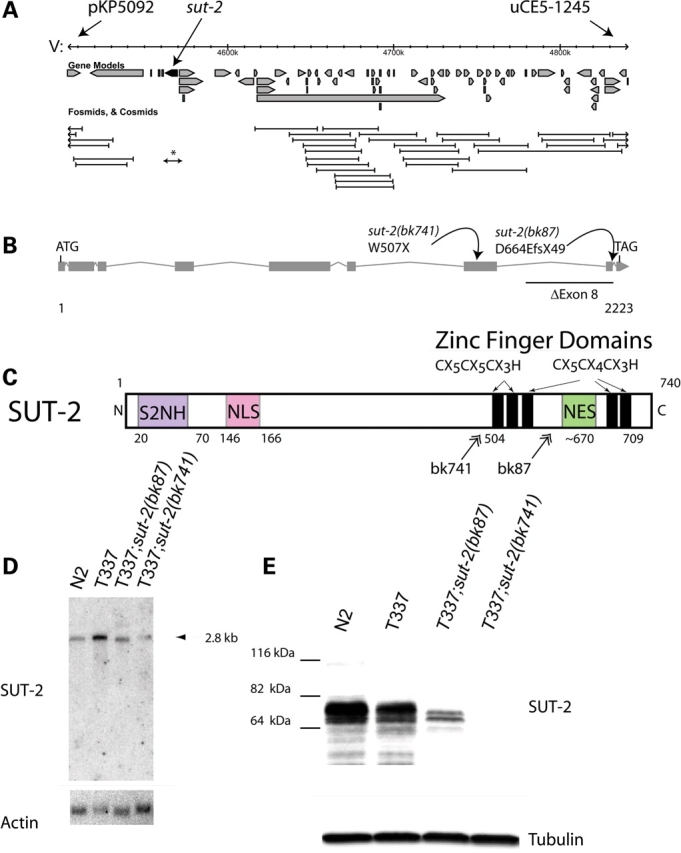

We used single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mapping (18) to localize the bk87 and bk741 mutations to chromosome II between polymorphic markers pKP5092 and uCe5-1245, an interval of ∼404 kb (Fig. 2A). To clone the responsible mutated gene, we injected both bk87and bk741 mutant line with pools of cosmid and fosmid clones spanning the genomic interval between pKP5092 and uCe5-1245. No cosmids/fosmids tested restored the Unc phenotype of the original T337 line. However, there was a 70 kb gap in cosmid/fosmid coverage. To span this gap, for each gene, long-range PCR (LRPCR) products were generated and injected into bk87 to form extrachromasomal transgene arrays. One gene, Y61A9LA.8, alleviated the suppression of the tau-induced Unc phenotype caused by bk741 and bk87. This gene has nine predicted exons and covers ∼10 kb of genomic sequence (Fig. 2B). We sequenced all exons of Y61A9LA.8 in both mutant strains. For bk741, we found a nonsense mutation in exon 6 encoding a W507X change. Allele bk87 contained an ∼1.6 kb deletion completely removing exon 8 and most of the flanking intronic sequences resulting in a frameshift at amino acid 664 and premature stop codon after appending 49 novel amino acids. Therefore, strains bk87 and bk741 contain mutations in gene Y61A9LA.8 which we call sut-2.

Figure 2.

Structure and expression of the sut-2 gene. (A) The minimum sut-2 region as determined by genetic mapping was between SNP markers pKP5092 and uCe5-1245, a physical interval of ∼404 kb. Predicted gene transcripts are shown as boxed arrows. Cosmid coverage is shown below the transcripts. A single 10 kb long-range PCR product containing the genomic sequence for Y61A9LA.8 is sufficient to rescue the sut-2 phenotype (asterisk). Other flanking cosmids did not rescue. (B) Predicted sut-2 mRNA transcript structure. Boxes depict exons, whereas forked lines show introns. The positions of bk87 and bk741 mutations are shown. (C) Predicted SUT-2 protein domains. SUT-2 N-terminal homology (S2NH) is a novel domain found in SUT-2 related proteins. Other domains are putative CCCH type ZF domains, a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a nuclear export signal (NES). Double arrows represent positions of premature termination of SUT-2 as a result of mutations in strains carrying bk87 and bk741 alleles. (D) Northern blot of polyA selected RNA from wild-type (N2), tau transgenic (T337) and both sut-2(bk87) and sut-2(bk741) mutants. Upper panel, wild-type sut-2 mRNA is ∼2.8 kb as detected by radiolabled probe complementary to sut-2. Lower panel, the same blot probed for actin. (E) Upper panel, an immunoblot of N2, T337, sut-2(bk87) and sut-2(bk741) worm total protein lysates probed with anti-SUT-2 protein antibodies. Lower panel, immunoblot of the same lysates probed for β-tubulin.

To validate the predicted sut-2 gene product, we sequenced seven cDNAs (yk490f4, yk559c2, yk644c2, yk1185e9, yk1337d10, yk1455d1 and yk1559d8) confirming the predicted open reading frame for sut-2 (Fig. 2C). Northern blot analysis shows a single species of sut-2 transcript of ∼2.8 kb consistent in size with the predicted 2.3 kb sut-2 open reading frame (Fig. 2D). To study SUT-2 protein, antibodies were raised against a truncated recombinant SUT-2 protein containing amino acids 503–740. Immunoblotting revealed a full length SUT-2 protein corresponding to a doublet band of ∼76 kDa consistent with the predicted 79 kDa size. The observed doublet could arise from post-translational modifications (PTMs) or alternative splicing. A faint higher molecular weight band of ∼115 kDa is also present and may arise from alternative splicing, PTMs, or alternative transcriptional start sites. Wormbase, the C. elegans genomic database, does not predict any variant sut-2 transcripts nor are these evident by northern blot analysis. The SUT-2 protein is abundantly expressed in both N2 and T337 lines, but is dramatically reduced in sut-2(bk87) and undetectable in sut-2(bk741) mutants (Fig. 2E).

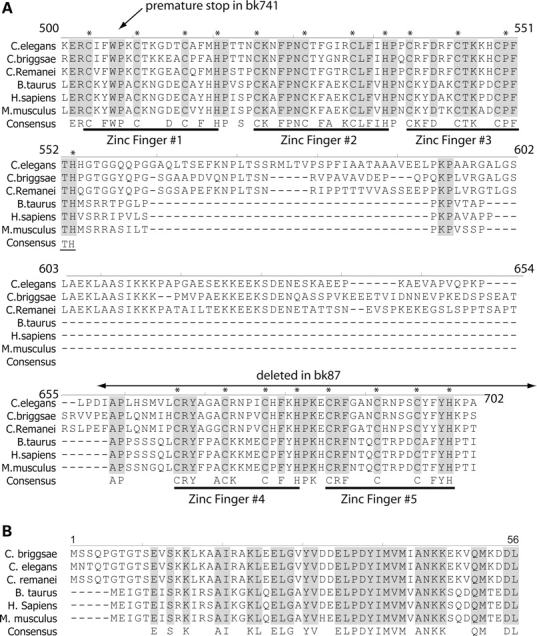

The C. elegans sut-2 gene encodes a protein predicted to contain five distinct C-terminal CCCH type zinc finger (ZF) domains, a short highly conserved N-terminal domain (S2NH), a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a nuclear export signal (NES) (Fig. 2C). The five SUT-2 ZF domains are distinguished from other CCCH type ZFs based on the spacing of the predicted zinc chelating residues. The first two ZF domains have an amino acid the arrangement of C-X5-C-X5-C-X3-H, whereas latter three are C-X5-C-X4-C-X3-H. Homology searching with these SUT-2 ZF domains revealed a small subfamily of ZF proteins with absolutely conserved spacing of the zinc chelating residues (Fig. 3A, alignment numbering corresponds to SUT-2 convention). This subfamily has a single member in most other animal species including: human, mouse, rat, cow, monkey, chicken, fish, sea urchin, beetle and fly (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). A stretch of 47 highly conserved amino acids near the N terminus is also shared among all members of this protein family, but not by any other ZF proteins (Fig. 3B). This SUT-2 N-terminal homology (S2NH) domain has not been previously described, but bears very limited homology to proline tryptophan isolucine (PWI) domains, although it lacks the core definitive PWI motif. The PWI domain is thought to bind either RNA or DNA and may be involved in transport or splicing of mRNAs (19).

Figure 3.

SUT-2 is conserved between nematodes and man. Shown is an alignment of the SUT-2 homologs from three nematode and three mammalian species. (A) Alignment of CCCH domains. (B) Alignment of SUT-2 N-terminal homology domain. * Represents putative metal chelating residues in CCCH finger domains. Also see Supplementary Material, Fig. S1 for full length protein alignment.

The intervening sequence between the N-terminal conserved sequences and the C-terminal ZF domains has limited sequence conservation among the species listed above. Although SUT-2 proteins do appear to have a NLS (20), the position of the NLS is not conserved. Similarly, prediction algorithms identifying NESs (21) suggest all SUT-2 family members have a NES sequence, although the position and sequence of the NES for each family member is not well conserved. The homologous mammalian SUT-2 (MSUT-2) protein from both humans and rodents share both the five CCHC and S2NH domains (Fig. 3). However, the C-terminal ZF sequence differs between mammals and nematodes in that nematodes harbor a C-terminal insert of ∼100 amino acids between ZFs 3 and 4.

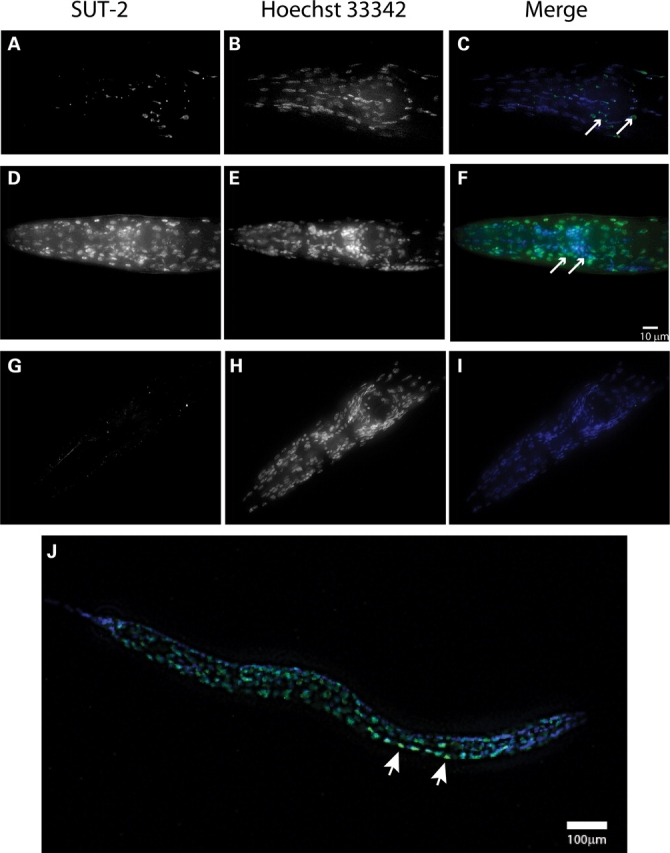

To investigate the expression pattern and sub-cellular localization of SUT-2 protein, we constructed transgenic strains expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagged version of SUT-2 protein under control of sut-2 promoter sequences (strain CK195). When we examined GFP fluorescence in CK195, we observed GFP present in a variety of tissues including neurons, germ cells, hypodermal cells and intestinal cells. Because the tauopathy phenotype is neuronal in origin (15), we examined the sub-cellular localization of SUT-2::GFP in the neurons of fixed animals (Fig. 4A). The neuronal SUT-2::GFP protein in strain CK195 is expressed throughout the nucleus and in intensely labeled nuclear and peri-nuclear foci. SUT-2::GFP protein shows significant overlap with Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain (Fig. 4C). We placed the CK195 transgene in the background of the T337 transgene and observed no change in SUT-2 GFP localization; the SUT-2::GFP transgene partially rescues sut-2(bk87) suggesting that the reporter produces some functional SUT-2 protein (data not shown). To directly observe native SUT-2 protein, we conducted immunostaining of fixed animals with SUT-2 antibodies which recapitulated the SUT-2::GFP protein expression pattern (Fig. 4D–F). SUT-2 protein substantially overlapped with Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain (Fig. 4E), confirming the SUT-2 proteins primary localization to the nucleus. However, faint cytoplasmic staining may indicate a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of SUT-2 protein. SUT-2 specific antibodies fail to stain sut-2(bk741) animals (Fig. 4G–I and E) consistent with western blotting data. In larvae, SUT-2 stains the nuclei of a variety of cell types, but is particularly prominent in motor neurons (Fig. 4J).

Figure 4.

SUT-2 protein is expressed primarily in the nucleus of neurons and other cell types. (A–C) Expression of SUT-2::GFP reporter transgene in the head of an adult N2 animal. (A) SUT-2::GFP fluorescence. (B) Hoechst 33342 nuclear marker fluorescence staining. (C) Merged images of (A and B), green is GFP-fluorescence, blue is Hoechst 33342. Arrows represent nerve ring neurons. (D–F) Depict immunocytochemical staining of wild-type worms with anti-SUT-2 specific antibodies (D) and Hoechst 33342 nuclear marker (E) and a Merged image (F) (green = SUT-2, blue = Hoechst 33342). Arrows represent nerve ring neurons. (G–I) Depict immunocytochemical staining of sut-2(bk741) worms with anti-SUT-2 specific antibodies and Alexa 488 fluorescent secondary antibodies (G) and Hoechst 33342 nuclear marker (H) and a merged image (I). (B and C) Are high magnification views of the heads of adult sut-2(bk87) and sut-2(bk741) animals, respectively. (D) Shows a high magnification view of the head of an adult N2 animal. (J) Shows an L2 stage wild-type larvae stained with SUT-2 specific antibodies (green) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Arrows represent nerve ring neurons. Arrowheads indicate normal ventral cord neurons with SUT-2 protein staining.

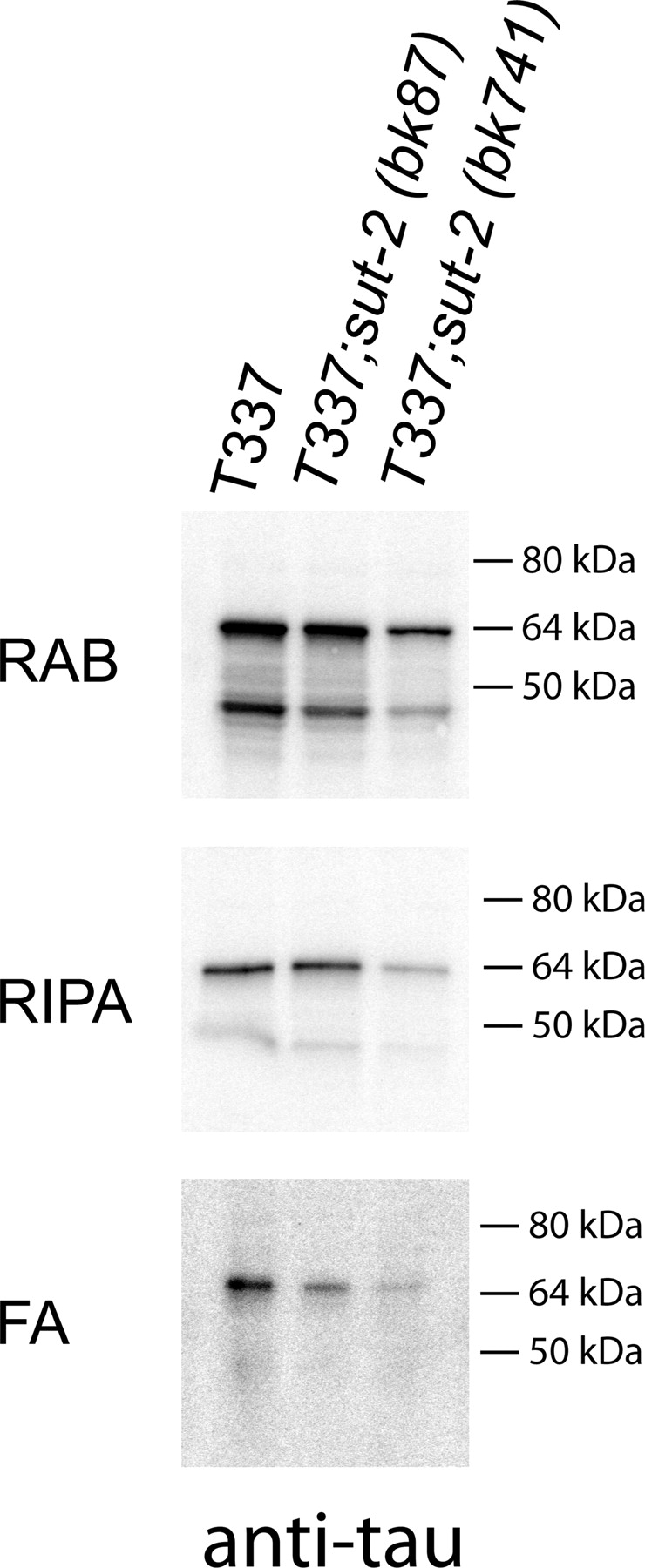

Insoluble aggregates of tau protein characterize human tauopathy disorders. Likewise, insoluble tau protein accumulates in the neurons of tau transgenic worms (15,22,23). To investigate how loss of sut-2 function affects tau aggregation, we examined the formation of insoluble tau protein in worms homozygous for the human tau T337 transgene and sut-2 mutations. To determine whether loss of sut-2 alters tau aggregation, we sequentially extracted worm lysates using buffers of increasing solublizing strength. We initially homogenized T337, T337;sut-2(bk87) or T337;sut-2(bk741) worm pellets in reassembly buffer (RAB), a high salt buffer, yielding the soluble tau fraction. We re-extracted material insoluble in RAB with RIPA, an ionic and non-ionic detergent containing buffer yielding the detergent soluble fraction. Subsequently, we recovered detergent insoluble material by extraction with formic acid (Fig. 5). We observed both sut-2(bk87) and sut-2(bk741) mutations caused a dramatic decrease in the levels of detergent insoluble aggregated tau. Therefore, SUT-2 normally plays a role in the accumulation of insoluble tau protein as sut-2 activity is required for the accumulation of appreciable amounts of insoluble tau in worm neurons.

Figure 5.

Loss of SUT-2 reduces accumulation of detergent insoluble tau species. Sequential extraction of insoluble tau protein from T337, T337;sut-2(bk87) and T337;sut-2(bk741) worm lysates yields soluble and insoluble tau. RAB contains tau solublized by high salt soluble tau fraction; RIPA contains detergent soluble tau, whereas FA contains the detergent insoluble material formic acid (FA) solublized protein.

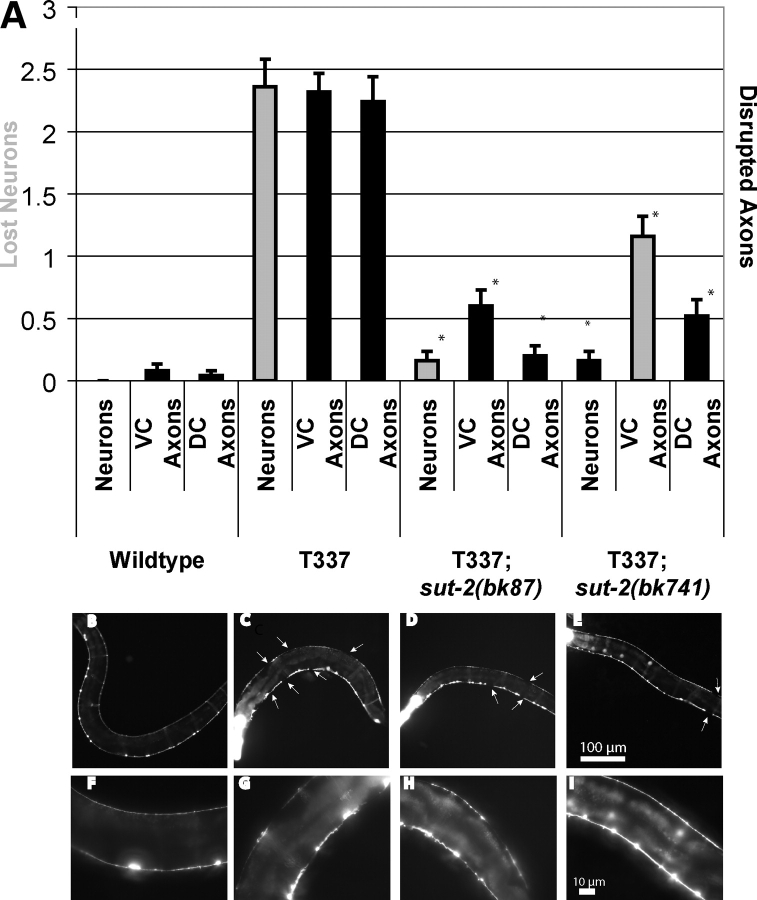

We monitored tau-induced neurodegeneration by observing the structural integrity of GABAergic neurons and their processes in tau transgenic animals with or without sut-2 mutations. To visualize neurons in living animals, we used the unc-25::GFP reporter transgene that expresses GFP in all 19 GABAergic motor neurons (24). In the wild-type worms, both the dorsal and ventral nerve cords are continuous and contain the normal complement of 19 inhibitory motor neurons (13 ventral D-type and 6 dorsal D-type GABAergic neurons—Fig. 6B and F). Previous work with tau transgenic animals demonstrated age-dependent discontinuities in both dorsal and ventral cord axons of GABAergic neurons (15). Both sut-2 mutations partially ameliorate the tau-induced neurodegenerative disruption of axons and loss of neurons (Fig. 6A). Partial suppression of neurodegeneration fits with the incomplete suppression of the locomotion phenotype in sut-2 mutants (Fig. 1).

Figure 6.

Loss of sut-2 reduces tau-induced neuronal damage. All strains shown contain a reporter transgene that marks the 19 VD and DD class GABAergic neurons with GFP (unc-25::GFP) from strain CZ1200. Left is anterior, down is ventral. (A) Measurement of neurodegenerative changes seen in wild-type, T337, T337;sut-2(bk87) and T337;sut-2(bk741). Three types of neurodegenerative changes were scored: neuronal loss (neurons), interruption of ventral cord continuity (VC axons) or interruption of dorsal cord continuity (DC axons). Measurements are the average from 25 animals for each strain and error bars are SEM. Using a ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test), both T337;sut-2(bk87) and T337;sut-2(bk741) are significantly different from the parental T337 strain for neuronal loss, ventral cord interruptions and dorsal cord interruptions (P < 0.0001). (B) Reporter strain CZ1200 in a non-transgenic wild-type background at 4 days of age. No neurodegenerative changes observed. (F) Higher magnification view of wild-type. (C) Four-day-old T337 animal exhibits loss of neurons, and interruptions of both dorsal and ventral nerve cords (white arrows) in all animals. (D) Four-day-old T337;sut-2(bk87) animal showing that loss of sut-2 ameliorates many of the defects seen in T337 alone. (E) Four-day-old T337;sut-2(bk741) animal showing that loss of sut-2 ameliorates many of the defects seen in T337 alone. (F–I) Higher magnification views of (B–E). Bright head fluorescence (in C–E) is myo-2::GFP, the marker transgene used to identify tau transgenic worms.

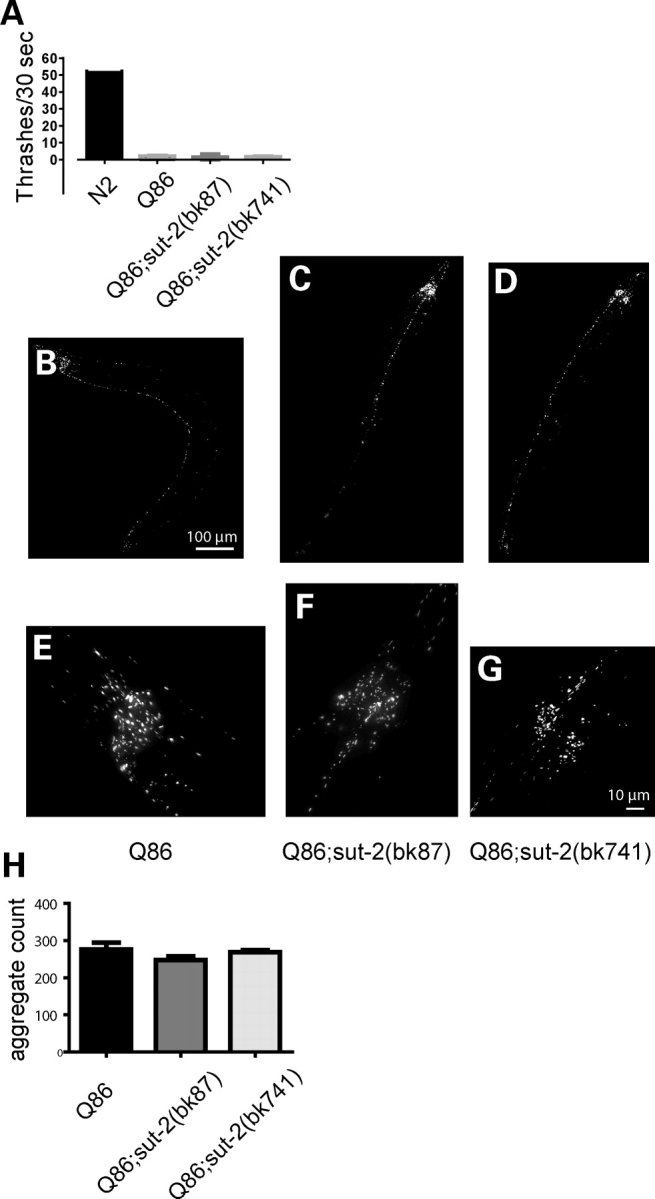

The work above demonstrates loss of sut-2 suppresses a phenotype related to protein-aggregation in tauopathies. We also investigated whether sut-2 could influence a polyglutamine-induced Unc phenotype in C. elegans. Like FTDP-17, polyglutamine-expansion diseases are caused by specific mutant proteins that form abnormal neuronal aggregates occurring in degenerating neurons. We used a transgenic polyglutamine C. elegans model (25) that has pan-neuronal expression of an 86 amino acid glutamine tract fused to yellow fluorescent protein (strain Q86-YFP). This strain has an Unc phenotype and visible yellow-fluorescent protein aggregates (26). When the Q86-YFP transgene was crossed with either sut-2 allele, there was no change in the Unc phenotype (Fig. 7A) or in the number of visible Q86-YFP aggregates relative to the parental Q86-YFP line (Fig. 7B–H). Thus sut-2 is not a general suppressor of protein-aggregation phenotypes.

Figure 7.

Loss of sut-2 does not modify polyglutamine phenotypes. (A) Graph of liquid thrashing assays for staged 4-day-old worms. Each column depicts the mean thrashing rate value (±SEM) for 20 worms: wild-type (N2)—52.6 ± 1.8, YFP-Q86—2.2 ± 0.4, YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk87)—1.6 ± 0.4 and YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk741)—1.9 ± 0.4; using the Kruskal–Wallis test, there are no statistically significant differences between YFP-Q86, YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk87) and YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk741) suggesting sut-2 does not modify the Q86 induced Unc phenotype. (B–G) Live image of polyQ aggregates of living worms. YFP-Q86 at low (B) and high magnification (E). YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk87) at low (C) and high magnification (F). YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk741) at low (D) and high magnification. (H) Graph of total number of YFP+ aggregates found per worm. Each data point represents the total number of YFP+ fluorescent polyQ86 deposits. The mean aggregate count (±SEM) for 10 worms scored: YFP-Q86–276 ± 19, YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk87)—247 ± 33 and YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk741)—269 ± 15. Using the Kruskal–Wallis test, there are no statistically significant differences between YFP-Q86, YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk87), and YFP-Q86;sut-2(bk741) suggesting sut-2 does not modify Q86 aggregate count.

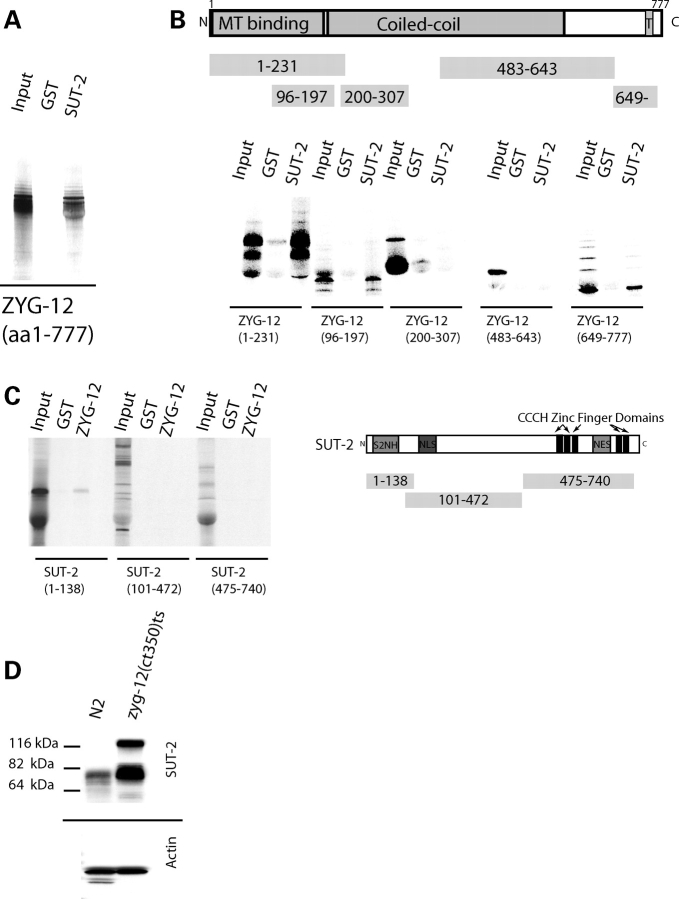

As the function of SUT-2 protein has not been previously investigated, we searched for interacting protein binding partners of SUT-2 to explore potential functions of SUT-2. To identify interacting proteins, we conducted a yeast two hybrid screen (27) using a lexA–SUT-2 fusion protein as bait. Briefly, we transformed yeast reporter strain L40ura− containing the lexA–SUT-2 bait expressing construct with the C. elegans cDNA library pRB-2. From 5 200 000 transformants, we recovered 41 colonies that activated both HIS3 and lacZ reporter genes under control of lexA operator sequences. From these, we isolated 22 cDNA clones specifically interacting with the SUT-2 protein but not a negative control protein (MS2 phage coat protein). All 22 specific clones encoded ZYG-12. To test whether SUT-2 and ZYG-12 proteins can bind in the absence of yeast proteins, we employed an in vitro protein binding assay. To generate SUT-2 protein, we expressed hexahistidine (HIS) tagged SUT-2 in Escherichia coli and purified the recombinant protein using nickel affinity resin. We mixed recombinant SUT-2 protein coated agarose beads with 35S labeled ZYG-12 protein generated by in vitro translation of a full length zyg-12 cDNA. 35S labeled ZYG-12 bound specifically to HIS-tagged SUT-2 protein coated beads but not HIS-tagged glutathione S-transferase (GST)-coated beads (Fig. 8A), demonstrating SUT-2 and ZYG-12 proteins interact into two independent assays.

Figure 8.

SUT-2 physically interacts with ZYG-12. (A) In vitro confirmation of the yeast two hybrid interaction between SUT-2 and ZYG-12. Radiolabled ZYG-12 protein was tested against immobilized recombinant GST–SUT-2 fusion protein or recombinant GST alone using GST pull-down assays. (B) SUT-2 binds both N- and C-terminal domains containing fragments of ZYG-12 in GST pull-down assays. T is a single pass transmembrane domain. (C) A radiolabled SUT-2 protein fragment containing the S2NH domain is sufficient for binding to immobilized ZYG-12. (D) Loss of zyg-12 causes upregulation of SUT-2 protein. SUT-2 80 kDa band is ∼3-fold more abundant in zyg-12(bw54) than in N2.

ZYG-12, the sole HOOK protein family member encoded by the C. elegans genome, has previously been implicated in embryonic centrosomal attachment to the nucleus (28). The Drosophila HOOK gene is the founding member of the HOOK gene family, and was first identified as the gene harboring mutations that caused hooked bristles (29). HOOK proteins consist of an N-terminal MT binding domain and central coiled-coil domain involved in dimerization (30).

We generated truncations of both ZYG-12 and SUT-2 to determine the protein domains involved in the ZYG-12/SUT-2 interaction, and tested them in the in vitro binding assay described above. We observe that both the N- and C-terminal portions of ZYG-12 are competent to bind MSUT-2 in vitro (Fig. 8B). Likewise, the SUT-2 S2NH domain is sufficient for binding to full length ZYG-12 in the same in vitro binding assay (Fig. 8C). This demonstrates two distinct SUT-2 S2NH domain binding sites on ZYG-12.

To explore the importance of the SUT-2/ZYG-12 interaction, we examined zyg-12(bw54), a mutant strain exhibiting temperature sensitive loss-of-function ZYG-12 for the expression of SUT-2 protein. We observe a dramatic compensatory upregulation of SUT-2 protein in response to loss of zyg-12 function (Fig. 8D). SUT-2 protein levels increase at least 3-fold in zyg-12(bw54). In addition, zyg-12 deficient animals produce an ∼115 kDa SUT-2 band of unknown origin suggesting possible PTM, covalent crosslinking or alternative splice isoforms of SUT-2.

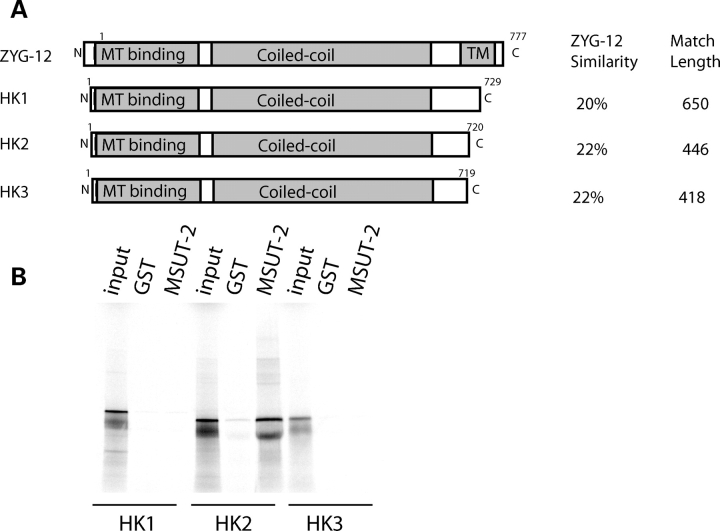

Both the human and mouse genomes encode three different HOOK proteins when compared with a single family member in C. elegans (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). HOOK1 binds MTs and regulates endocytic processing (30,31). HOOK2 may play a role in aggresome formation and/or centrosomal function (32,33). HOOK3 protein is required for organization and maintenance of Golgi apparatus (GA) through its binding to both the MT cytoskeleton and the GA membranes (34,35). ZYG-12 shares 20% identity with HOOK1 over 650 amino acids, 22% identity with HOOK2 over 446 amino acids and 22% identity with HOOK3 over 418 amino acids (Fig. 9A). Since ZYG-12 binds SUT-2, we investigated whether any of the human HOOK protein homologs bind to human MSUT-2 using the in vitro protein binding assay described above. HOOK2, but not HOOK1 or HOOK3, binds to MSUT-2 (Fig. 9B), suggesting analogous function for HOOK2 and ZYG-12.

Figure 9.

Human MSUT-2 binds HOOK2. (A) Comparison of shared domains in ZYG-12 and human HOOK1-3. See Supplementary Material, Fig. S2 for detailed alignments. (B) In vitro protein binding assays between radiolabled human MSUT-2 and immobilized recombinant human HOOK1, HOOK2 and HOOK3 proteins. Immobilized recombinant GST is negative control.

DISCUSSION

We generated a C. elegans model for tauopathy disorders by expressing a human mutant tau cDNAs in neurons (15). The resulting model system exhibits many of the biochemical and cellular features of bona fide human tauopathies. Here we describe the identification of sut-2, a gene essential for tau-induced neurodegeneration. Loss of sut-2 ameliorates the tau-induced neuronal dysfunction seen in tau transgenic worms. In sut-2 mutants, the Unc phenotype is markedly reduced. Detergent insoluble tau, a characteristic of human diseases with tau pathology and this transgenic tauopathy model, is also reduced. Furthermore, neurodegenerative changes in GABAergic neurons are significantly decreased. Thus loss of a single gene restores worms to a near normal phenotype in the presence of pathological levels of mutant human tau. Conversely, sut-2 fails to modulate either poly-glutamine aggregation or poly-glutamine neurotoxicity. Thus, sut-2 is not likely a global regulator of protein aggregation or neurotoxicity.

SUT-2 protein family members contain five distinct C-terminal CCCH type ZF domains, a highly conserved S2NH domain, a NLS and a NES. The distinctive spacing of the putative Zn chelating residues distinguishes SUT-2 ZF domains from other CCCH ZF domain proteins. The ZF domains 1 and 2 follow the pattern C-X5-C-X5-C-X3-H, whereas ZFs 3, 4 and 5 are C-X5-C-X4-C-X3-H. The SUT-2 family of proteins has absolutely conserved spacing of the zinc chelating residues (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1), and a single family member is observed in the genomes of all sequenced animal species. Although only limited experimental data exist for the function of the SUT-2 family of ZF proteins, they are related to a larger group of C-X8-C-X4-C-X3-H type ZF proteins, some of which have been intensively studied. There are many different C-X8-C-X4-C-X3-H type ZF domain proteins with over 2600 complied into the PFAM database (36). Proteins with C-X8-C-X4-C-X3-H type ZF motifs have been demonstrated to carry out diverse functions in the cell including binding DNA, binding RNA, mediating protein–protein interactions and shuttling protein cargoes between nucleus and cytoplasm (37). Thus, by inference with homology to the C-X8-C-X4-C-X3-H type ZF motifs, the SUT-2 family of proteins could be involved in a wide array of different cellular processes. Interestingly, SUT-2 family members typically contain both an NLS and NES, although the relative position of each is not well conserved. The juxtaposition of both an NES and NLS in the same molecule suggests the SUT-2 family of proteins may shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm as part of its normal function.

The physical interaction between the C. elegans hook proteins, ZYG-12 and SUT-2, is the key finding concerning SUT-2's normal function (Fig. 8A). We demonstrate that the conserved S2NH domain mediates the interaction between SUT-2 and the N terminus of ZYG-12 (Fig. 8B and C). The compensatory upregulation of SUT-2 protein levels in zyg-12(bw54) mutant animals provides in vivo support for the observed physical interaction between SUT-2 and ZYG-12 and suggests a regulatory relationship between ZYG-12 and SUT-2 levels (Fig. 8D). ZYG-12 is a member of the HOOK protein family, and has been demonstrated to mediate the attachment of centrosomes to the nucleus during C. elegans embryogenesis (28). The HOOK protein family includes the original founding Drosophila melanogaster ortholog HOOK, its paralog HOOK-like and three mammalian hook protein family members (HOOK1, HOOK2 and HOOK3) (38). All members of this protein family have an N-terminal MT binding and central coiled-coil domain. The N-terminal domain binds either centrosomal or normal MTs, whereas the coiled-coil domain has been shown to mediate homo-dimerization (30). Functionally, HOOK proteins link sub-cellular structures to the MT cytoskeleton and participate in diverse processes including aggresome formation, centrosomal attachment, endosomal processing and GA organization. At the molecular level, HOOK proteins self-associate and bind MTs to promote proper localization, motility or function of sub-cellular membranous compartments (31–33,35,38). In worms, ZYG-12 may carry out one or more of these roles. Previous work has demonstrated that ZYG-12 binds several other proteins including dynein and SUN-1, a regulator of centrosomal attachment to the nucleus (28). Here, we show the sole C. elegans HOOK protein ZYG-12 binds SUT-2. However, in mammals, the three HOOK homologs specialize in distinct functions. HOOK1 binds MTs and regulates endocytic processing (30). HOOK2 participates in the transport or accumulation of aggregated proteins into large pericentriolar aggresomes (32,33). HOOK3 protein participates in the cellular localization or organization of the GA through its binding to both the MT cytoskeleton and membranes on the GA surface (34,35). The binding of C. elegans SUT-2 with ZYG-12 and human MSUT-2 to HOOK2 suggests that SUT-2 protein family members may play a conserved role in centrosome function and processing of protein aggregates via the aggresome.

Aggresomes arise when the cell accumulates excessive levels of misfolded or aggregated proteins. The constituents of aggresomes include misfolded proteins, protein aggregates and the chaperones and proteasomes tasked with degrading abnormal proteins. HOOK2 protein is a component of aggresomes (32,33). Aggresomes form when the ubiquitin proteasome and chaperone systems become overwhelmed (39). Peri-nuclear foci reminiscent of centrosomes are observed for proteins localized to aggresomes (40,41). Aggresome formation depends upon MT-based transport to concentrate small protein aggregates dispersed throughout the cell into a single centrally located juxtanuclear/centrosomal site (40). The dynein motor complex mediates transport of protein aggregate cargos allowing for centralized concentration or sequestration of protein aggregates (41). Once centralized, aggresome contents can be degraded by autophagy. For example, autophagosomes were implicated in the turnover of peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22), because this protein was observed in aggresomes in the Schwann cells of mice overexpressing mutant PMP22 (42). Taken together, these findings suggest aggregated protein may be turned over by the aggresome/autophagy pathway as a mechanism of last resort when other mechanisms including the ubiquitin proteasome system and chaperone-mediated protein refolding activities are no longer capable of clearing protein aggregates. As abnormal tau has been shown to disrupt MT transport (43), pathological tau may also impair the MT-based transport required for aggresome formation resulting in a feedback inhibition of degradation of aggregates.

Mutations in MAPT, pathological Aβ, abnormal tau phosphorylation, physical neuronal injury or other neuronal insults can lead to excess tau release from MTs. Hypothetically, if excess free tau is not rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin/proteasome system as mediated by CHIP (44) or tau proteases (45,46), tau aggregates may form highly neurotoxic low level tau oligomers. If not degraded, oligomeric tau can fibrillize into neurotoxic protofilaments that in turn organize into neurofibrillary tangles. Oligomeric or protofilamentous tau can be degraded prior to the formation of mature neurofibrillary tangles by an active transport mediated process. Tau aggregates can be transported to aggresomes and subsequently degraded by incorporation into autophagosomes. The rapid degradation of abnormal tau is critical to continued neuronal function. Otherwise, pathological tau inhibits transport and thus degradation of multimeric tau species, activating a self-reinforcing cascade of tau aggregation and neurotoxicity culminating in neurodegeneration and the formation of end stage neurofibrillary tangles.

How SUT-2 modulates tau aggregation and neurotoxicity remains unclear. However, the interaction of MSUT-2 with HOOK2 may be informative. Since HOOK2 is implicated in aggresome formation and loss of SUT-2 prevents the accumulation of insoluble tau, the mechanism may involve the removal of abnormal or toxic tau species via an aggresome dependent mechanism. However, other equally plausible mechanisms for SUT-2 function are clearly consistent with this data.

In summary, we demonstrated that loss of a single gene ameliorates the toxic effects of tau in a transgenic C. elegans model of tauopathy disorders. Hence, in human tauopathies, the functional inhibition of a single protein may be a valid neuroprotective strategy. We suggest MSUT-2 may be an attractive target for the generation of small molecule inhibitors. Clearly, more needs to be understood about MSUT-2 function before the full ramifications of MSUT-2 inhibition can be fully appreciated. Nonetheless, MSUT-2 serves as a novel candidate pharmacological target for the inhibition of tau pathology. The functions of SUT-2 in nematodes and MSUT-2 in mammals will be a topic of future investigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains

N2 (Bristol) was used as wild-type C. elegans and maintained as previously described (47). Tau transgenic line T337-1 (CK10) was used for the suppressor screen. Line CK10–bkIs10[Paex-3::tau–V337M), Pmyo-2::GFP] carries a chromosomally integrated transgene encoding the 1N4R isoforms of human tau carrying the V337M FTDP-17 mutation with expression driven by the pan-neuronal promoter aex-3, and has a pronounced Unc phenotype (15). Strain CZ1200 has an integrated unc-25::GFP transgene expressed in GABAergic neurons (48).

Positional cloning of sut-2

Tau transgenic worms were mutagenized using ethyl nitrosurea essentially as described (49). Worms were mutagenized and screened as previously described (50). Sut-2 mutant lines were subjected to SNP mapping conducted as described using CK15 as the Hawaiian strain (50). The rapid SNP mapping method of Davis et al. (51) was adopted for mapping sut-2. Using these methods, sut-2(bk87) was mapped to the interval between markers pKP5092 and uCe5-1245. To rescue the Sut-2 phenotype, pools of cosmids were injected at 30 ng/μl each with Pmyo-2::dsRED at 10 ng/μl as a co-injection marker. Individual gene rescue was carried out using genomic LRPCR as recommended by the manufacturer (Takara, Inc.). These LRPCR products were subsequently injected individually at 70 ng/μl with 90 ng/μl pBluescript II KS(+) as carrier and 10 ng/μl of Pmyo-2::dsRED. The exons and flanking sequences for Y61A9LA.8 were amplified by PCR and sequenced. The sequences for sut-2 mutant exons were compared with the sequence for N2 and CK10 to identify mutations.

Behavioral assays

Liquid thrashing assays were performed in 20 μl of M9 media (42 mm Na2HPO4, 22 mm KH2PO4, 86 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgSO4) on Teflon-printed slides as previously described (15). Worms were allowed to settle and thrashes counted for 30 s.

Protein extraction

Tau fractions were obtained as described (52). To determine whether aggregated tau accumulates or is absent from sut-2 animals strains were sequentially extracted using buffers of increasing solublizing strengths and compared with the parental T337 strain (15). First, worms were homogenized in high salt reassembly buffer [RAB-High Salt (0.1 m MES, 1 mm EGTA, 0.5 mm MgSO4, 0.75 m NaCl, 0.02 m NaF, 0.5 mm PMSF, 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.0)] and ultra-centrifuged at 50 000× gravity yielding the soluble fraction (supernatant) and an insoluble pellet. Next, the RAB insoluble material was re-extracted with an ionic and non-ionic detergent containing RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 1% NP40, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% DOC, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mm PMSF, 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 8.0) and centrifuged as above yielding abnormal tau in the supernatant. Finally, the detergent insoluble pellet was re-extracted with 70% formic acid to solublize detergent insoluble tau. The three fractions were analyzed using quantitative western blotting with tau specific primary and 125I-labeled secondary antibodies.

C. elegans polyglutamine model

The polyQ neurotoxicity model of Brignull et al. (53) was partially recapitulated by generating a transgene derived from the PF25B5.3::Q86-YFP plasmid, a generous gift from Richard Morimoto. The PF25B5.3::Q86-YFP plasmid was microinjected at a concentration of 65 ng/μl with pBS KS II (+) as a carrier at 60 ng/μl for a total injected DNA concentration of 125 ng/μl. Resulting extrachromasomal lines were integrated by exposure to a gamma ray dosage of 3600 R. Line bkIS241 was out-crossed twice. Strains carrying bk87 and bk741 were crossed with bkIS241 yielding strains CK245 and CK246, respectively. bkIS241, CK245 and CK246 were scored for the severity of the Unc phenotype at 3 days of age using liquid thrashing assays as described above. Comparisons of polyQ aggregate abundance were made by photographing 3-day-old animals and counting the discrete number of YFP positive foci in the entire animal (see below).

Live mount fluorescence microscopy

Live worms were mounted as described (54). Imaging of live worms was done on a Nikon Eclipse TE300 epi-fluorescent microscope. Images were acquired using a Photometrics SenSys™ cooled CCD camera and IPLab acquisition software (BD Biosciences Bioimaging). Images were deconvolved using MicroTome™ deconvolution software (BD Biosciences Bioimaging). Image segmenting to count aggregates was done with IPLab software.

Immunoblotting

Protein samples were boiled 5 min and loaded onto 10% pre-cast SDS–PAGE gels (Biorad). For quantitative immunoblotting, we detected human tau using antibody 17026 at a dilution of 1:3000 (a gift from Virginia Lee) as described previously. We used anti-tubulin antibody at a dilution of 1:1000 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). SUT-2 antibody was prepared as described below and used at a dilution of 1:1000. 125I-labled goat anti-mouse or goat-anti-rabbit IgG were the secondary antibody reagents used at a dilution of 1:1000 (New England Nuclear). Signals were measured using a Packard Cyclone phosphorimager.

Immunocytochemistry

Worms were fixed in paraformaldehyde and permeablized by freeze cracking as described (55). Fixed and permeablized animals were counterstained with 16 µm Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain in PBS. Fixed whole animals were stained with SUT-2 specific affinity purified rabbit antibodies at a dilution of 1:500. Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes) was used as the secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:500.

Measurement of neuronal degeneration

The unc-25::GFP transgene was crossed into the background of the tau transgenic strains assayed. Fifty worms of each genotype were developmentally staged and analyzed for neuronal structure defects as previously described (50).

Yeast two hybrid screening

Yeast two hybrid screening was carried out as described (56), except that yeast strain L40ura− carrying pLexA–SUT-2 plasmid was transformed with the LamdaACT RB-2 library and plated on SD-trp-leu-his, 100 mm 1,2,4 3-amino triazole. Colonies were picked after 5 days and cDNA-containing plasmids were rescued into E. coli. Recovered cDNA plasmids were reintroduced into L40 containing either pLexA–SUT-1 or pLexA–MS2 coat protein. Those cDNAs that activated expression with SUT-1, but not MS2 coat protein, were analyzed further.

Recombinant protein purification

The SUT-2 protein expression construct was prepared by inserting the sut-2cDNA into the pGEX 6P-1 expression vector (Pharmacia) to generate a construct encoding a GST–SUT-2 fusion protein. The GST moiety allows one step affinity purification of recombinant protein on glutathione coupled sepharose beads. A log phase culture of BL21(DE3) cells carrying the pGEX–SUT-2 vector was induced for 3 h at 37°C with shaking. Glutathione sepharose (Pharmacia) was used as the affinity resin; cells were harvested, lysed and recombinant protein was purified as previously described (57).

SUT-2 antibody preparation

SUT-2 and MSUT-2 antibodies were prepared commercially using the Sigma Genosys antibody service. Purified recombinant GST–SUT-2 protein was used as the immunogen. Antisera were affinity purified using pure SUT-2 protein cleaved from the GST moiety using the Genosys antibody affinity purification service.

GST pull-down assays

In vitro protein-binding assays were performed as described except the binding buffer contained 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Tween-20, 100 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4 (56). His-tagged GST or GST–SUT-2 fusion protein was bound to glutathione-sepharose as described (56). The amount of GST or GST–SUT-2 protein bound to beads was determined by eluting the bound protein and analyzing them by SDS–PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining. Radiolabeled (35S) proteins were produced using the TNT reticulocyte lysate (Promega) according to the manufacturer's methods. Labeled protein was then added to equivalent amounts of glutathione beads to which either GST alone or GST–SUT-2 fusion protein was bound and incubated with beads at 4°C with gentle rotation for 60 min. Beads were pelleted, washed five times in binding buffer and eluted by boiling in SDS–PAGE sample buffer. Eluted, labeled proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE. In the figures, the amount of material shown in lanes marked ‘input’ is 10% of the amount added in the pull-down experiments.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Grant (B.C.K.) and by NIA grant PO1 AG17586 (G.D.S.).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank James H. Thomas for advice regarding C. elegans genetics and strains. We thank the C. elegans Genetics Center for providing strains. We thank Leo Anderson, Harmony Danner, Elaine Loomis, Lindsey Foley, Shannon Thomas and Tobin Martin for outstanding technical assistance. We thank Yuji Kohara for the sut-2 cDNAs, Andrew Fire for providing C. elegans expression vectors, Yishi Jin for strain CZ1200, Richard Morimoto for the PF25B3.3::Q86-YFP plasmid, Virginia Lee for antibody 17026 and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (NICHD) for the β-tubulin antibody E7.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee V.M.Y., Goedert M., Trojanowski J.Q. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingram E.M., Spillantini M.G. Tau gene mutations: dissecting the pathogenesis of FTDP-17. Trends Mol. Med. 2002;8:555–562. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spillantini M.G., Bird T.D., Ghetti B. Frontotemporal Dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: a new group of tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:387–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutton M., Lendon C.L., Rizzu P., Baker M., Froelich S., Houlden H., Pickering-Brown S., Chakraverty S., Isaacs A., Grover A., et al. Association of missense and 5'-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poorkaj P., Bird T.D., Wijsman E., Nemens E., Garruto R.M., Anderson L., Andreadis A., Wiederholt W.C., Raskind M., Schellenberg G.D. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spillantini M.G., Murrell J.R., Goedert M., Farlow M.R., Klug A., Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong M., Zhukareva V., Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V., Wszolek Z., Reed L., Miller B.I., Geschwind D.H., Bird T.D., McKeel D., Goate A., et al. Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct Tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science. 1998;282:1914–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goedert M., Jakes R., Crowther R.A. Effects of frontotemporal dementia FTDP-17 mutations on heparin-induced assembly of tau filaments. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:306–311. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nacharaju P., Lewis J., Easson C., Yen S., Hackett J., Hutton M., Yen S.H. Accelerated filament formation from tau protein with specific FTDP-17 missense mutations. FEBS Lett. 1999;447:195–199. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yen S., Easson C., Nacharaju P., Hutton M., Yen S.H. FTDP-17 tau mutations decrease the susceptibility of tau to calpain I digestion. FEBS Lett. 1999;461:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goate A.M. Monogenetic determinants of Alzheimer's disease: APP mutations. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 1998;54:897–901. doi: 10.1007/s000180050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrer M., Gwinnhardy K., Hutton M., Hardy J. The genetics of disorders with synuclein pathology and parkinsonism. Hum. Mol. Gen. 1999;8:1901–1905. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medori R., Tritschler H.J., LeBlanc A., Villare F., Manetto V., Chen H.Y., Xue R., Leal S., Montagna P., Cortelli P., et al. Fatal familial insomnia, a prion disease with a mutation at codon 178 of the prion protein gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992;326:444–449. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202133260704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitamoto T., Ohta M., Doh-ura K., Hitoshi S., Terao Y., Tateishi J. Novel missense variants of prion protein in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease or Gerstmann–Straussler syndrome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;191:709–714. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraemer B.C., Zhang B., Leverenz J.B., Thomas J.H., Trojanowski J.Q., Schellenberg G.D. Neurodegeneration and defective neurotransmission in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of tauopathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9980–9985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533448100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goedert M., Baur C.P., Ahringer J., Jakes R., Hasegawa M., Spillantini M.G., Smith M.J., Hill F. PTL-1, a microtubule-associated protein with tau-like repeats from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 1996;109:2661–2672. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.11.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mcdermott J.B., Aamodt S., Aamodt E. ptl-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans gene whose products are homologous to the tau microtubule-associated proteins. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9415–9423. doi: 10.1021/bi952646n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wicks S.R., Yeh R.T., Gish W.R., Waterston R.H., Plasterk R.H. Rapid gene mapping in Caenorhabditis elegans using a high density polymorphism map. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:160–164. doi: 10.1038/88878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blencowe B.J., Ouzounis C.A. The PWI motif: a new protein domain in splicing factors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:179–180. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange A., Mills R.E., Lange C.J., Stewart M., Devine S.E., Corbett A.H. Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:5101–5105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600026200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.la Cour T., Kiemer L., Molgaard A., Gupta R., Skriver K., Brunak S. Analysis and prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2004;17:527–536. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandt R., Gergou A., Wacker I., Fath T., Hutter H. A Caenorhabditis elegans model of tau hyperphosphorylation: induction of developmental defects by transgenic overexpression of Alzheimer's disease-like modified tau. Neurobiol. Aging. 2009;30:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyasaka T., Ding Z., Gengyo-Ando K., Oue M., Yamaguchi H., Mitani S., Ihara Y. Progressive neurodegeneration in C. elegans model of tauopathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005;20:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kabashi E., Valdmanis P.N., Dion P., Spiegelman D., McConkey B.J., Vande Velde C., Bouchard J.P., Lacomblez L., Pochigaeva K., Salachas F., et al. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:572–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brignull H.R., Morley J.F., Morimoto R.I. The stress of misfolded proteins: C. elegans models for neurodegenerative disease and aging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007;594:167–189. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-39975-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gidalevitz T., Ben-Zvi A., Ho K.H., Brignull H.R., Morimoto R.I. Progressive disruption of cellular protein folding in models of polyglutamine diseases. Science. 2006;311:1471–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1124514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fields S., Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein–protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malone C.J., Misner L., Le Bot N., Tsai M.C., Campbell J.M., Ahringer J., White J.G. The C. elegans hook protein, ZYG-12, mediates the essential attachment between the centrosome and nucleus. Cell. 2003;115:825–836. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohr O.L. The second chromosome recessive hook bristles in Drosophila melanogaster. Hereditas. 1927;9:169–179. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer H., Phistry M. Mutations in the Drosophila hook gene inhibit endocytosis of the boss transmembrane ligand into multivesicular bodies. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:1205–1215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer H., Phistry M. Genetic analysis of hook, a gene required for endocytic trafficking in Drosophila. Genetics. 1999;151:675–684. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szebenyi G., Hall B., Yu R., Hashim A.I., Kramer H. Hook2 localizes to the centrosome, binds directly to centriolin/CEP110 and contributes to centrosomal function. Traffic. 2007;8:32–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szebenyi G., Wigley W.C., Hall B., Didier A., Yu M., Thomas P., Kramer H. Hook2 contributes to aggresome formation. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sano H., Ishino M., Kramer H., Shimizu T., Mitsuzawa H., Nishitani C., Kuroki Y. The microtubule-binding protein Hook3 interacts with a cytoplasmic domain of scavenger receptor A. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7973–7981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walenta J.H., Didier A.J., Liu X., Kramer H. The Golgi-associated hook3 protein is a member of a novel family of microtubule-binding proteins. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:923–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bateman A., Birney E., Cerruti L., Durbin R., Etwiller L., Eddy S.R., Griffiths-Jones S., Howe K.L., Marshall M., Sonnhammer E.L. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:276–280. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthews J.M., Sunde M. Zinc fingers—folds for many occasions. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:351–355. doi: 10.1080/15216540216035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpson F., Martin S., Evans T.M., Kerr M., James D.E., Parton R.G., Teasdale R.D., Wicking C. A novel hook-related protein family and the characterization of hook-related protein 1. Traffic. 2005;6:442–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olzmann J.A., Li L., Chin L.S. Aggresome formation and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:47–60. doi: 10.2174/092986708783330692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kopito R.R. Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:524–530. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnston J.A., Ward C.L., Kopito R.R. Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1883–1898. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fortun J., Dunn W.A., Jr, Joy S., Li J., Notterpek L. Emerging role for autophagy in the removal of aggresomes in Schwann cells. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:10672–10680. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10672.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandelkow E.M., Stamer K., Vogel R., Thies E., Mandelkow E. Clogging of axons by tau, inhibition of axonal traffic and starvation of synapses. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:1079–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dickey C.A., Yue M., Lin W.L., Dickson D.W., Dunmore J.H., Lee W.C., Zehr C., West G., Cao S., Clark A.M., et al. Deletion of the ubiquitin ligase CHIP leads to the accumulation, but not the aggregation, of both endogenous phospho- and caspase-3-cleaved tau species. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6985–6996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0746-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karsten S.L., Sang T.K., Gehman L.T., Chatterjee S., Liu J., Lawless G.M., Sengupta S., Berry R.W., Pomakian J., Oh H.S., et al. A genomic screen for modifiers of tauopathy identifies puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase as an inhibitor of tau-induced neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2006;51:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sengupta S., Horowitz P.M., Karsten S.L., Jackson G.R., Geschwind D.H., Fu Y., Berry R.W., Binder L.I. Degradation of tau protein by puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase in vitro. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15111–15119. doi: 10.1021/bi061830d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cinar H., Keles S., Jin Y. Expression profiling of GABAergic motor neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Stasio E.A., Dorman S. Optimization of ENU mutagenesis of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mutat. Res. 2001;495:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(01)00198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kraemer B.C., Schellenberg G.D. SUT-1 enables tau-induced neurotoxicity in C. elegans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:1959–1971. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis M.W., Hammarlund M., Harrach T., Hullett P., Olsen S., Jorgensen E.M. Rapid single nucleotide polymorphism mapping in C. elegans. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishihara T., Hong M., Zhang B., Nakagawa Y., Lee M.K., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M.Y. Age-dependent emergence and progression of a tauopathy in transgenic mice overexpressing the shortest human tau isoform. Neuron. 1999;24:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brignull H.R., Moore F.E., Tang S.J., Morimoto R.I. Polyglutamine proteins at the pathogenic threshold display neuron-specific aggregation in a pan-neuronal Caenorhabditis elegans model. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:7597–7606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0990-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mello C., Fire A. In: Caenorhabditis elegans Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Epstein H., Shakes D., editors. Vol. 48. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 452–480. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crittenden S.L., Kimble J. Confocal methods for Caenorhabditis elegans. Meth. Mol. Biol. 1999;122:141–151. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-722-x:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kraemer B., Crittenden S., Gallegos M., Moulder G., Barstead R., Kimble J., Wickens M. NANOS-3 and FBF proteins physically interact to control the sperm-oocyte switch in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frangioni J.V., Neel B.G. Solubilization and purification of enzymatically active glutathione S-transferase (pGEX) fusion proteins. Anal. Biochem. 1993;210:179–187. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.