Abstract

Introduction

Almost all descriptions of attempts to quit smoking have focused on what happens after an abrupt quit attempt and end once a smoker relapses. The current study examined the day-to-day process preceding a quit or reduction attempt in addition to the daily process after a failure to quit or reduce.

Methods

We recruited 220 adult daily cigarette smokers who planned to quit abruptly, to quit gradually, to reduce only, or to not change on their own. Participants called a voice mail system each night for 28 days to report cigarette use for that day and their intentions for smoking for the next day. No treatment was provided.

Results

Three main findings emerged: (a) The large majority of participants did not show a simple pattern of change but rather showed a pattern of multiple transitions among smoking, abstinence, and reduction over a short period of time; (b) most of those who reported an initial goal to quit abruptly actually reduced; and (c) daily intentions to quit strongly predicted abstinence, while daily intentions to reduce weakly predicted reduction.

Discussion

We conclude that the day-to-day process of attempts to change smoking among nontreatment seekers is much more dynamic than previously thought. This suggests that extended treatment beyond initial lapses and relapses and during postcessation reduction may be helpful.

Introduction

Current descriptions of smoking behavior focus on whether individuals smoke as usual, abstain from smoking according to point prevalence or continuous abstinence measures, lapse (i.e., smoke one puff of a cigarette), or relapse (i.e., return to usual smoking; Hughes et al., 2003). More recent descriptions focus on other outcomes, such as the transtheoretical model’s progressive stages toward smoking cessation (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1992; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). Most of these descriptive studies measure behavior only once every few months (Collins & Graham, 2002); thus, it is unclear how often and how rapidly transitions among these outcomes can occur. Furthermore, natural history studies of self-quitters and randomized controlled trials of treatment seekers usually focus only on outcomes related to abstinence and relapse, stop data collection when a smoker lapses, do not distinguish between lapses and relapses, and do not distinguish reduction in cigarettes per day (CPD) from smoking as usual (Cohen et al., 1989; Hughes, Keely, & Naud, 2004; Hughes et al., 2003).

Prior work has challenged these descriptions, finding that smokers often quit impulsively (Larabie, 2005; West & Sohal, 2006) and that attempts to stop smoking can result in reduced smoking rather than abstinence or return to usual level of smoking (Hughes & Carpenter, 2005). When assessed more often than once every few months, intentions related to smoking, such as plans to quit, reduce, or not change smoking, can change rapidly (Hughes, Keely, Fagerström, & Callas, 2005). However, none of these studies examined smoking and intention transitions on a daily basis. Although some studies have examined whether smoking occurs or does not occur on a daily basis (Shiffman, Paty, Gnys, Kassel, & Hickcox, 1996), none have analyzed these data to determine how often smokers transition among different intention stages (i.e., to quit, reduce, or not change smoking) and different smoking stages (i.e., abstinence, lapse, relapse, and reduction).

Such a study examining these transitions on a daily basis has been accomplished with marijuana users. In a study of regular marijuana users who were trying to quit or reduce on their own, we found the daily process of changing intentions and marijuana use to be complex, with frequent and rapid fluctuations (Hughes, Peters, Callas, Budney, & Livingston, 2008). Intentions to quit or reduce changed from day to day, and there were multiple transitions among usual use, reduction, and abstinence over the course of just 1 month. The purpose of the current study was to investigate whether this complexity also occurs with self-attempts to change smoking.

To do this, we conducted a prospective study of adult daily cigarette smokers who reported initial goals to (a) quit abruptly, (b) quit gradually, (c) reduce only, or (d) not change their use on their own. We have previously used data from this study in a preliminary report that found initial goals indicate motivation to quit smoking in an order where the goal to quit abruptly indicates the strongest motivation to quit, followed by the goal to quit gradually, then the goal to reduce only, and then the goal to not change (Peters, Hughes, Callas, & Solomon, 2007). In this paper, we address the day-to-day processes preceding a quit attempt, during abstinence and after relapse. We believe a more detailed understanding of the descriptive patterns of quitting or reducing in nontreatment seekers might be helpful to public health efforts to assist the majority of smokers who attempt to change on their own (Cokkinides, Ward, Jemal, & Thun, 2005; Shiffman, Brockwell, Pillitteri, & Gitchell, 2008).

Methods

Study design

The study was a prospective 28-day natural history investigation of four groups of cigarette smokers who, in the next 30 days, planned to (a) quit abruptly, (b) quit gradually, (c) reduce only, or (d) not change their smoking. Participants called a confidential voice mail system each night and reported the number of cigarettes smoked that day and their intentions for smoking for the following day. This study offered no treatment. Participants were compensated on a schedule that prior work has shown increases compliance rates (Budney, Moore, Vandrey, & Hughes, 2003; Helzer, Badger, Rose, Mongeon, & Searles, 2002). The maximum compensation that a participant could earn was $228.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via three different types of newspaper advertisements in 12 cities in the northeastern and mid-Atlantic United States. Advertisements that recruited two groups of smokers who planned to quit abruptly or gradually read: “Cigarette smokers who plan to quit smoking wanted for University of Vermont research study. This study does not offer treatment. Compensation for completing brief phone interviews and mailed questionnaires about experiences trying to quit.” This advertisement did not specify whether the study targeted smokers planning to quit via abrupt or gradual cessation. Advertisements that recruited one group of smokers who planned to reduce substituted the word “reduce” for the word “quit” in the above advertisement. This advertisement did not distinguish between reducing as a prelude to cessation and reducing for its own sake (i.e., without planning to make a quit attempt). A third advertisement for the fourth group of those who did not plan to change their smoking substituted the words “not change” for “quit” in the above advertisement.

Procedure

Initial telephone call—screen.

Interested smokers were screened via telephone for initial criteria of being at least 18 years of age, smoking at least 1 cigarette/day, owning a touch-tone phone, and not having made a quit attempt or having reduced by more than 20% from their usual level of smoking in the past month. Callers selected one of four mutually exclusive options representing their goal for the next 30 days: quit abruptly, quit gradually, reduce only, or not change. Eligible participants provided verbal consent and began the study that day. Recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the University of Vermont Committees on Human Research.

Initial telephone call—baseline assessment.

Immediately after providing verbal consent, participants completed baseline assessments. Participants were again asked to report their goal for the next 30 days to ensure a consistent report; however, they were not asked if they had set a specific target date to quit or reduce. Participants were then asked to rate how much they planned to quit smoking for good in the next 30 days on a previously validated 11-rung Intention to Quit Ladder (Carpenter, Hughes, Solomon, & Callas, 2004; Hughes et al., 2005) with anchors at 0 for “definitely do NOT” and 10 for “definitely DO.” Mailed questionnaires collected information on demographics; nicotine dependence (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence [FTND]; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991); and histories of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and caffeine use.

Monitoring.

Each night for the next 28 days, participants with goals of quitting abruptly, quitting gradually, and reducing only, as well as the first 35 participants with a goal of not changing, called a confidential, toll-free voice mail system. They were specifically instructed to report the exact number of cigarettes smoked that day and only one of the following choices about their intention for smoking for the following day: “quit for good,” “quit for the day,” “reduce,” or “do not plan to try to quit or reduce.” Because the incidence of endorsements of quit for the day was small (6%), we combined the first two categories. We did not ask whether an intention to reduce was part of a quit attempt or for its own sake nor whether reduction represented reduction to a level less than their usual CPD or from the prior day.

The second 35 participants with a goal of not changing did not report CPD or intentions daily. Instead, they were contacted weekly by research assistants who administered timeline follow-back (Brown et al., 1998) procedures so that we could test for reactivity to the daily monitoring. The daily monitoring and weekly monitoring control groups’ reports of CPD both showed a very small nonsignificant decline over time (−1.5 cigarettes/28 days) that did not differ between the two groups; that is, we found no evidence of reactivity. Because the first 35 control participants completed procedures similar to the three other groups, we include only this group in the analyses below.

Data analysis

Because of the many possible outcomes that could be gleaned from daily data, we structured our results according to relevant clinical questions. We include all descriptive outcomes in Table 1 but highlight results that we deem clinically important.

Table 1.

Outcomes during the 28-day study period

| Initial goal |

||||

| Outcome | Quit abruptly (n = 36) | Quit gradually (n = 43) | Reduce only (n = 42) | Not change (n = 31) |

| % With at least one episode of abstinence | 44 | 21 | 14 | 6 |

| % With at least one episode of reduction | 67 | 74 | 53 | 16 |

| % With multiple episodes of abstinence | 14 | 2 | 10 | 3 |

| % With multiple episodes of reduction | 42 | 44 | 31 | 10 |

| % With ≥7 days of consecutive abstinence | 19 | 12 | 2 | 3 |

| % With ≥7 days of consecutive reduction | 19 | 14 | 2 | 0 |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) no. of abstinent days | 0 (0–8.25) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) no. of reduced days | 8.5 (1–17.75) | 3 (0–11) | 1 (0–4.5) | 0 (0–0) |

Note. Abstinence is defined as at least 1 day of reporting smoking zero cigarettes. Reduction is defined as at least 1 day of reporting smoking 50% of baseline cigarettes per day.

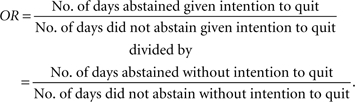

SAS (version 9, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for survival analysis, and trends over time were determined using multilevel growth modeling or binary growth modeling with dichotomous outcomes (MLwiN v1.1, Multilevel Models Project, Institute of Education, University of London, London, UK). SPSS 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all other analyses. For the analysis evaluating whether daily intentions predicted abstinence or reduction, only the participants who reported at least twice an intention to change (abstain or reduce) as well as 2 days of no intention to change were retained. Less than half of participants reported a mix of both intentions to quit/reduce and intentions to not change. We computed odds ratios (ORs) for each participant:

|

We then used the Mantel–Haenszel method for combining the ORs (Cooper & Hedges, 1994).

We defined a quit attempt as a report of at least 1 day of not smoking any cigarettes. We assumed that an entire 24 hr of abstinence due to unavailability of cigarettes or smoking restrictions would be very rare, and thus, daylong abstinence represented a quit attempt. Although this definition excludes individuals who may attempt to quit but do not last an entire day without smoking (Carpenter & Hughes, 2005), a 24-hr quit attempt is the most commonly used definition (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999). Like most reduction studies (Hughes & Carpenter, 2005), we considered a reduction in cigarette use to be clinically significant if the reduction from baseline was at least 50%. Among those included, we are missing data on 7% of days. To prevent 1 or 2 days of missing data from falsely truncating episodes of abstinence or reduction, we imputed missing values using the mean of the preceding and succeeding values when possible and last observation carried forward when not possible.

Results

Recruitment

We recruited 235 participants; 15 (6%) prematurely terminated the study for various reasons (e.g., did not want to provide Social Security numbers to receive compensation). Of the 220 participants who completed the study, 50 reported a goal to quit abruptly, 50 to quit gradually, 50 to reduce only, and 70 to not change.

We excluded the data from participants for four reasons: assignment to the group that reported CPD and intentions only weekly (see above; 35 participants), noncompliance defined as completing less than 70% of the daily calls (21 participants), absence of baseline self-report of usual CPD (9 participants), or discrepant goals at the screen versus baseline assessment portions of the initial telephone call (3 participants). For the analyses below, there remained 152 smokers: 36 with a goal to quit abruptly, 43 with a goal to quit gradually, 42 with a goal to reduce only, and 31 with a goal to not change.

Participant characteristics

We reported on participant characteristics in our prior paper (Peters et al., 2007). Our participants were mostly female, White, middle-aged, high school graduates, not married, and not employed full time. They smoked about a pack of CPD on average, had a mean FTND score at the threshold of defining dependence (Mikami et al., 1999), and started smoking cigarettes during late adolescence. Our participants were similar to smokers in the 2000 National Health Interview Survey (Hughes, 2004) in terms of race (76% vs. 78% White), CPD (20 vs. 18 CPD), and age of onset of smoking (17.8 vs. 17.7 years) but appeared to be slightly older (47 vs. 41 years), more likely to be female (59% vs. 47%), and more likely to be high school graduates or of higher education (92% vs. 77%).

Due to the use of different recruitment cities for different advertisements, the groups varied on race (p < .01) and marital status (p = .01). Analyses using these two variables as covariates did not change results. For simplicity, we present only the unadjusted analyses.

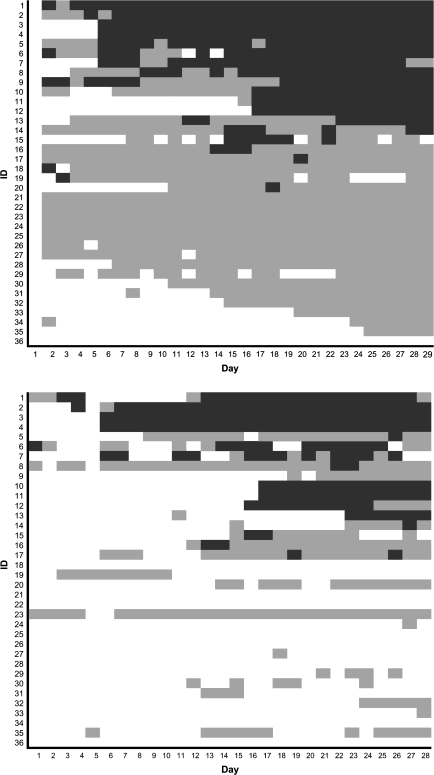

Example outcomes

Figure 1 uses the data from those whose initial goal was to quit abruptly to illustrate outcomes for individual participants. The top panel illustrates intention outcomes, and the bottom panel represents actual smoking outcomes. Those participants who intended to change the most are placed at the top of the first panel, and the second panel reflects the same order of participants.

Figure 1.

Panel 1: Intention outcomes for individual participants with an initial goal to quit abruptly. Panel 2: Smoking outcomes for individual participants with an initial goal to quit abruptly. Abstinence is represented by thick diagonal crosshatches, reduction of ≥50% from baseline cigarettes per day by thin horizontal stripes, and no change by an absence of texture. Participant identification numbers were reassigned, and the most successful participants placed at the top of the first panel. Participants reported their intentions for the following day, for example, on Day 1, participants reported what they intended to do on Day 2, and these intentions are represented on Day 2. The second panel reflects the order of participants in the first panel.

The most commonly described pattern in the cessation literature is that a smoker decides to not change his smoking and smokes the same number of cigarettes for multiple days, followed by an intention to quit, then an attempt to not smoke any cigarettes for several days, and then relapses back to his usual number of CPD. Very few participants showed this pattern: only three (8%) participants (no. 3, 4, and 12) did so for daily intentions and only four (11%) participants (no. 3, 4, 10, and 11) did so for actual smoking behavior. In contrast, the resultant pattern for many smokers was one of multiple transitions among abstinence, reduction, and no change in smoking. For example, participant no. 7 did not change for 5 days, abstained for 2 days, returned to usual smoking for 3 days, abstained for 2 days, returned to usual smoking for 2 days, vacillated between abstinence and reduction eight times in 12 days, and then returned to usual smoking for 2 days. In addition, the figure illustrates that many participants who stated they planned to quit in the next month made no changes whatsoever during the study: for example, 16 (44%) never reported 1 day of intending to quit in the month and 20 (56%) never reported 1 day of a quit attempt. In addition, many of the outcomes were incongruent with initial goals for smoking change: For example, 32 participants (89%) who said they planned to quit abruptly in the next month reported a daily intention to reduce and 24 (67%) reported at least 1 day of reduction.

Graphs for those whose initial goal was to quit gradually or only to reduce showed similar patterns. These graphs and the graph for the no-change group are available at http://www.uvm.edu/∼hbpl. Other descriptive outcomes are described in Table 1.

How often did daily intentions change?

Among the three groups with an initial goal to change their smoking (goals to quit abruptly, quit gradually, or only reduce), daily intentions changed a median of two times (25th–75th percentile = 0–6) during the month. Over half (59%) reported multiple transitions among intentions to change.

How often did participants attempt to quit or reduce their smoking?

Among the 79 participants whose initial goal was to stop abruptly or gradually, 32% actually quit smoking during the 28 days (i.e., achieved at least 1 day of abstinence) and 71% reduced at least 1 day. Of the 42 participants who planned only to reduce, 53% reduced and 14% abstained. Among the 121 participants in the three groups with an initial goal to change their smoking, 8% of participants reported multiple episodes of abstinence and 39% reported multiple episodes of reduction during the 28 days.

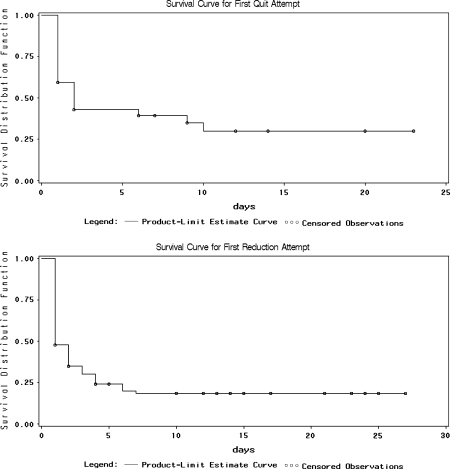

What was the duration of attempts to quit or reduce?

To determine the duration of quit and reduction attempts, we used survival curves for the first attempt to quit or reduce (Figure 2). Among the 33 participants who attempted to quit, the median duration of the first quit attempt was 2 days (95% CI = 1–10 days). Among the 103 participants who attempted to reduce, the median duration of the first reduction attempt was 1 day (95% CI = 1–2 days).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for attempts to quit and to reduce. The first panel represents the survival curve for participants’ first attempt to quit. The second panel represents the survival curve for participants’ first attempt to reduce.

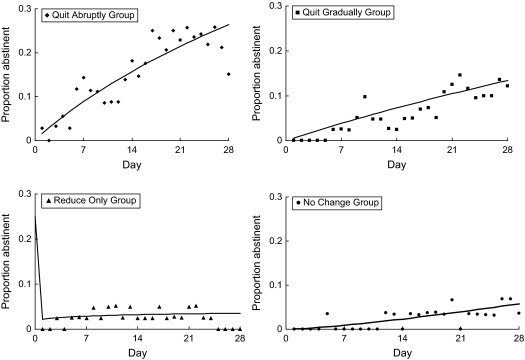

Did the probability of intending to quit or actually quitting smoking change over time?

Figure 3 shows how the probability of intending to quit or actually quitting smoking changed over time. Daily intentions to quit increased over time among those with a goal to quit abruptly (e.g., 12% on Day 1 of the study to 39% on Day 28, p < .01), quit gradually (0%–15%, p < .01), and reduce only (0%–11%, p < .01). Intentions to quit did not show a significant trend among those with a goal to not change (4%–4%, p = .73).

Figure 3.

Probability of abstinence. Trends over time in the proportion of participants who abstained from smoking on each day of the study. The first panel represents this trend for participants with a goal to quit abruptly, the second panel represents the trend for participants with a goal to quit gradually, the third panel represents the trend for participants with a goal to reduce only, and the fourth panel represents the trend for participants with a goal to not change.

The probability of abstinence increased over time for the quit abruptly group (3%–15%, p < .01), the quit gradually group (0%–12%, p < .01), and even for the no-change group (0%–4%, p = .02). The reduction group showed virtually no trend over time in the probability of abstinence (0% on Day 1 to 0% on Day 28, p = .38).

Did daily intentions prospectively predict abstinence or reduction?

The observed mean percentage of abstinence given an intention to quit was 46.0% and given an intention to reduce or not change was 6.5%. Thus, the mean OR (95% CI) that an intention to quit was followed by a day of abstinence versus a day of either reduction or no change in the same participant was 13.6 (8.4–21.9, p < .01). Forty participants were retained in this meta-analysis. The test of homogeneity was not rejected (p = .08).

Across the 54 participants who reported an intention to reduce, the observed mean percentage of reduction/abstinence given an intention to reduce was 17.4% and given an intention to not change was 13.5%. Thus, the mean OR (95% CI) that an intention to reduce was followed by a day of reduction or abstinence versus a day of no change was 1.5 (1.0–2.3, p = .05; homogeneity test p = .96).

Discussion

Our three major findings are (a) the large majority of smokers who attempted to change on their own did not show a simple pattern of change; they reported multiple transitions across smoking, reduction, abstinence, lapse, and relapse states over a short period of time; (b) many of those who stated they planned to quit actually reduced; thus, reduction was much more common than anticipated; and (c) daily intentions to quit strongly predicted abstinence but daily intentions to reduce only weakly predicted reduction. Other findings include (d) most attempts to change only lasted 1 or 2 days and (e) daily intentions to quit increased over time, as did the likelihood of quitting smoking.

Complexity of attempts to stop or reduce smoking

Many smokers made no change in their smoking over the month, but among those who did, few showed the simple pattern of smoking, abstinence, and relapse. Few self-changers achieved prolonged abstinence or reduction, and many actually made multiple attempts at change, both of abstinence and reduction, even over the course of 1 month. These results are consistent with our prior report that intentions often change over short periods of time (Hughes et al., 2005). Whether it is best to describe these repeated attempts as part of the initial quit attempt, new quit attempts, recycling, or recovery is unclear. Regardless, the multiple attempts to change in a short period of time contradict the simplistic descriptions of outcomes in randomized controlled trials (i.e., do individuals quit smoking or not, do they relapse or not; Shiffman, 2006) and suggest that fluctuations in smoking and intentions are more common than implied in most models of change. Our findings support other complex descriptions of smoking change (Resnicow & Page, 2008), including different factors that promote lapse versus promote recovery (Swan & Denk, 1987; Wileyto et al., 2005), variable resumption patterns following relapse (Conklin et al., 2005), fluctuations between abstinence and smoking over time (Wetter et al., 2004), and variability in quit date adherence (Borelli, Papandonatos, Spring, Hitsman, & Niaura, 2004).

Prevalence of reduction

Many participants actually reduced their smoking instead of quitting or in addition to quitting. Although we expected to observe reduction as an outcome in smokers who reported an initial goal to quit gradually or reduce only, we were surprised by the amount of reduction in those who reported a goal to quit abruptly. The incidence of reduction was high in this group (67%), and according to Figure 1, reduction preceded 15 of 24 quit attempts. Several studies have found that smoking reduction among smokers who are not trying to quit is common (Meyer, Rumpf, Schumann, Hapke, & John, 2003; West, McEwen, Bolling, & Owen, 2001) and often leads to abstinence (Hughes & Carpenter, 2006). Fewer studies have examined smoking reduction among smokers who are trying to quit (Hughes & Carpenter, 2005). One analysis found that smokers who tried to quit and then reduced their smoking were more likely to quit by the end of the following year (Hyland et al., 2005). Our study replicated this finding, notably over the shorter time period of 1 month.

Predictive findings

Our previous report from this sample of self-changers demonstrated that initial goals predict the probability of making a quit attempt (Peters et al., 2007). These initial goal predictions were based on a single self-report at the onset of the study. The current study found that intentions reported daily also predict outcomes.

Reporting intentions to quit or reduce on a daily basis might be expected to be reactive, that is, to increase the probability of quitting or reducing (Rowan et al., 2007). However, we found no evidence of reactivity when we compared outcomes in those who did versus did not monitor intentions daily. We did find that the likelihood of intending to quit or actually quitting increased over the month for most goal groups. These increases could indicate that motivation builds over time, even in the face of failed quit or reduction attempts.

Further, we found that an intention to quit on 1 day strongly predicted abstinence, but an intention to reduce on 1 day only weakly predicted reduction or abstinence. Many current models of health behavior change hypothesize that a change in intention produces a behavior change (Azjen & Madden, 1986; Prochaska et al., 1992). Our results support these models for quitting intentions but not for reduction intentions. This difference is also consistent with our prior work that initial intentions to reduce are less serious than intentions to quit (Peters et al., 2007). Reports of intentions to reduce may have been due to experimenter demand. Although we attempted to minimize experimenter demand via an impersonal voice mail system, smokers may still have been reluctant to admit that they did not want to change their smoking.

Implications for treatment

Our finding that many smokers fail after 1 or 2 days of a change attempt yet try to change again in the very near future suggests that treatment should not focus so much on the outcome of a single quit attempt but rather on working through several rapidly occurring quit or reduction attempts to achieve eventual abstinence. Because behavior and intentions change so rapidly, smoking change should be considered a process (Shiffman, 2006). Instead of a lapse being understood as a treatment failure, it should be considered an important signal during the cessation process that indicates a time to intervene before the lapse progresses to a relapse. For example, treatment providers ought to recognize that motivation to change smoking may still be high after an initial lapse and should urge individuals to immediately change their cessation strategy or treatment. In fact, intensifying treatment use, rather than stopping treatment, may be more appropriate upon a lapse. For example, although labeling on nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products instructs smokers to stop NRT upon a lapse, continuing NRT during a lapse increases later abstinence sevenfold (Shiffman et al., 2006). As another example, the three studies with the largest long-term quit rates (Anthonisen et al., 1994; Hall, Humfleet, Reus, Muñoz, & Cullen, 2004; Hughes, Hymowitz, Ockene, Simon, & Vogt, 1981) all continued treatment after a lapse.

Our finding that reduction is common, even in those with a goal to quit, may also have implications for cessation. Because reduction often preceded or followed cessation, reduction might serve as a signal that smokers are motivated to change their smoking, even after a failed quit attempt. Reduction may be a stage in the process of changing smoking, similar to a lapse, rather than an outcome analogous to abstinence failure.

Assets and limitations

The major asset of this study is the prospective, daily examination of intentions and smoking behavior among smokers after they developed an intention to change their smoking but before they implemented any behavior to that end. Although a series of analyses from a prior study has utilized daily collection of data to examine the processes surrounding a quit attempt, these analyses were among treatment seekers (e.g., Shiffman et al., 2007) and focused more on situational antecedents of lapses and relapses. Our description of behavior before, during, and after multiple quit/reduction attempts is unusual. In addition, the use of nontreatment seekers, smokers trying to quit both abruptly and gradually, and smokers trying only to reduce provides a more diverse and generalizable sample than prior studies. The use of an impersonal method to record intentions and smoking and the inclusion of a control group of smokers not trying to change are also assets.

The major limitations of this study are the small sample size and the absence of data on long-term (i.e., beyond 28 days) outcomes. In addition, the different goal groups were recruited via convenience sampling in different cities and thus may not be a generalizable sample to all smokers. This study did not use biochemical or collateral verification of quit or reduction attempts; however, verification may not be essential in nonintervention studies (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002). Another limitation is our definition of a 50% reduction from baseline CPD. If a participant reported an intention to reduce and then reduced by less than 50%, this scenario was classified as an intention failing to predict behavior. Thus, our observed weak correspondence between intentions to reduce and reduction outcomes may be due to a discrepancy between participants’ versus our definition of reduction. Finally, the study did not ask several relevant questions such as whether smokers set a quit or reduction date, whether they used NRT in their change attempts, social influences on intentions and outcomes, and reasons for not seeking treatment.

Conclusions

Our findings contradict traditional models of change and indicate that the day-to-day process of changing smoking among self-changers is more dynamic and complex than previously described. Daily, prospective observations revealed multiple fluctuations of intentions, abstinence and reduction, and a less than robust relationship between intentions and behavior change. These results suggest that quitting is more of a dynamic process (i.e., a “chronic, relapsing disorder”), even over the short term. Thus, treatments need to accommodate these shifts through uninterrupted intervention across a series of abstinence episodes, lapses, and relapses. Although such treatment may be occurring in the field, with a few exceptions (Hall et al., 2004; Shiffman et al., 2006), empirical studies on how best to intervene on these multiple transitions are lacking and sorely needed.

Funding

This study was funded by Institutional Training Grant DA07242 (ENP), DA11557 (JRH), and Senior Scientist Award DA-00490 (JRH), all from the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Declaration of Interests

Dr. Hughes has accepted honoraria or consulting fees from Abbot Pharmaceuticals; Academy for Educational Development; Acrux DDS; Aradigm; American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry; Atrium; Cambridge Consulting; Celtic Pharmaceuticals; Cline, Davis, and Mann; Constella Group; Concepts in Medicine; Consultants in Behavior Change; Cowen Inc.; Cygnus; Edelman PR; EPI-Q; Evotec; Exchange Limited; Fagerström Consulting; Free and Clear; Health Learning Systems; Healthwise; Insyght; Invivodata; Johns Hopkins University; J Reckner; Maine Medical Center; McNeil Pharmaceuticals; Nabi Pharmaceuticals; Novartis Pharmaceuticals; Oglivy Health PR; Pfizer Pharmaceuticals; Pinney Associates; Reuters; Shire Health London; Temple University of Health Sciences; United Biosource; University of Arkansas; University of Auckland; University of Cantabria; University of Greifswald; University of Kentucky; U.S. National Institutes of Health; Xenova and ZS Associates. Ms. Peters has no competing interests to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laura Solomon, Peter Callas, and Shelly Naud for assistance in data analysis and writing of the paper; Saul Shiffman, Karl Fagerström, and Matthew Carpenter for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript; and Amy Livingston, Patti Gannon, Casey Tuck, and Kelsey Hughes for their assistance in conducting this study.

References

- Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azjen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1986;22:453–474. [Google Scholar]

- Borelli B, Papandonatos G, Spring B, Hitsman B, Niaura R. Experimenter-defined quit dates for smoking cessation: adherence improves outcomes for women but not for men. Addiction. 2004;99:378–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans MD, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Vandrey RG, Hughes JR. The timecourse and significance of cannabis withdrawal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:393–402. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Hughes JR. Defining quit attempts: What difference does a day make? Addiction. 2005;100:257–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Callas PW. Both smoking reduction and motivational advice increase future cessation among smokers not currently planning to quit. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:371–381. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1999. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1999;50:869–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Lichtenstein E, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Gritz ER, Carr CR, et al. Debunking myths about self-quitting: Evidence from 10 prospective studies of persons who attempt to quit smoking by themselves. American Psychologist. 1989;44:1355–1365. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.11.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides VE, Ward E, Jemal A, Thun MJ. Under-use of smoking-cessation treatments: Results from the National Health Interview Survey, 2000. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Graham JW. The effect of the timing and spacing of observations in longitudinal studies of tobacco and other drug use: Temporal design considerations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:S85–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Perkins KA, Sheidow AJ, Jones BL, Levine MD, Marcus MD. The return to smoking: 1-year relapse trajectories among female smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7:533–540. doi: 10.1080/14622200500185371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Muñoz RF, Cullen J. Extended nortriptyline and psychological treatment for cigarette smoking. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2100–2107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T, Kozlowski L, Frecker R, Fagerström K.-O. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A review of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Badger GJ, Rose GL, Mongeon JA, Searles JS. Decline in alcohol consumption during two years of daily reporting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:551–558. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GH, Hymowitz N, Ockene JK, Simon N, Vogt TM. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) Preventive Medicine. 1981;10:476–500. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(81)90061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Data to estimate the similarity of tobacco research samples to intended populations. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:177–179. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. The feasibility of smoking reduction: An update. Addiction. 2005;100:1074–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. Does smoking reduction increase future cessation and decrease disease risk? A qualitative review. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;6:739–749. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely JS, Fagerström KO, Callas PW. Intentions to quit smoking change over short periods of time. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:653–662. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Peters EN, Callas PW, Budney AJ, Livingston AE. Attempts to stop or reduce marijuana in non-treatment seekers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Levy DT, Rezaishiraz H, Hughes JR, Bauer JE, Giovino G, et al. Reduction in amount smoked predicts future cessation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:221–225. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larabie L. To what extent do smokers plan quit attempts? Tobacco Control. 2005;14:425–428. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C, Rumpf H.-J., Schumann A, Hapke U, John U. Intentionally reduced smoking among untreated general population smokers: Prevalence, stability, prediction of smoking behaviour change and differences between subjects choosing either reduction or abstinence. Addiction. 2003;98:1101–1110. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami I, Akechi T, Kugaya A, Okuyama T, Nakano T, Okamura H, et al. Screening for nicotine dependence among smoking-related cancer patients. Cancer Science. 1999;90:1071–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Hughes JR, Callas PW, Solomon LJ. Goals indicate motivation to quit smoking. Addiction. 2007;102:1158–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. In: Hersen M, Eisler RM, Miller PM, editors. Progress in behavior modification. Sycamore, IL: Sycamore Press; 1992. pp. 184–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Page SE. Embracing chaos and complexity: A quantum change for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1382–1389. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan PJ, Cofta-Woerpel L, Mazas CA, Vidrine JI, Reitzel LR, Cinciripini PM, et al. Evaluating reactivity to ecological momentary assessment during smoking cessation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:382–389. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Reflections on smoking relapse research. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:15–20. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Gwaltney CJ, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, et al. Prediction of lapse from associations between smoking and situational antecedents by ecological momentary assessment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JA, Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: Within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:366–379. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Scharf DM, Shadel WG, Gwaltney CJ, Dang Q, Paton SM, et al. Analyzing milestones in smoking cessation: Illustration in a nicotine patch trial in adult smokers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4:129–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Denk CE. Dynamic models for the maintenance of smoking cessation: Event history analysis of late relapse. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1987;10:527–554. doi: 10.1007/BF00846653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, McEwen A, Bolling K, Owen L. Smoking cessation and smoking patterns in the general population: A 1-year follow-up. Addiction. 2001;96:891–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96689110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Sohal T. “Catastrophic” pathways to smoking cessation: Findings from national survey. British Medical Journal. 2006;332:458–460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38723.573866.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Cofta-Gunn L, Fouladi RT, Cinciripini PM, Sui D, Gritz ER. Late relapse/sustained abstinence among former smokers: A longitudinal study. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:1156–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wileyto EP, Patterson F, Niaura R, Epstein LH, Brown RA, Audrain-McGovern J, et al. Recurrent event analysis of lapse and recovery in a smoking cessation clinical trial using bupropion. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7:257–268. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.