Abstract

Taste disorders, including taste distortion and taste loss, negatively impact general health and quality of life. To understand the underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms, we set out to identify inflammation-related molecules in taste tissue and to assess their role in the development of taste dysfunctions. We found that 10 out of 12 mammalian Toll-like receptors (TLRs), type I and II interferon (IFN) receptors and their downstream signaling components are present in taste tissue. Some TLRs appear to be selectively or more abundantly expressed in taste buds than in non-gustatory lingual epithelium. Immunohistochemistry with antibodies against TLRs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 confirmed the presence of these receptor proteins in taste bud cells, of which TLRs 2, 3 and 4 are expressed in the gustducin-expressing type II taste bud cells. Administration of TLR receptor ligands, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) that mimics bacterial or viral infection, activates the IFN signaling pathways, up-regulates the expression of IFN-inducible genes but down-regulates the expression of c-fos in taste buds. Finally, systemic administration of IFNs augments apoptosis of taste bud cells in mice. Taken together, these data suggest that TLR and IFN pathways function collaboratively in recognizing pathogens and mediating inflammatory responses in taste tissue. This process, however, may interfere with normal taste transduction and taste bud cell turnover and contributes to the development of taste disorders.

Keywords: chemosensory disorders, Toll-like receptors, interferons, inflammation

Introduction

Taste disorders, including ageusia, hypogeusia and dysgeusia, can have a substantial, negative impact on general health and quality of life. For example, taste disorders are known to contribute to or exacerbate anorexia, malnutrition, and depression. In other clinical situations, such as cancer and AIDS, ensuing taste abnormalities are associated with poor patient outcome.1–3 In spite of the clinical significance of taste dysfunction, its underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. At present, there is no specific treatment for severe generalized taste loss.4

Inflammation has been shown to be a common factor in many of the conditions and diseases associated with taste disorders. Patients with infectious diseases such as upper respiratory viral infection, oral cavity infection, or viral hepatitis, frequently develop taste abnormalities characterized by increased detection and recognition thresholds for various taste stimuli.5–9 Autoimmune diseases, e.g. Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosis, are known to affect taste function as well.10–12 Lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice display a reduced preference for sucrose along with the elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and interferon (IFN)-γ.13, 14 The strong association between inflammation and taste disorders suggests that inflammation may play a role in the pathogenesis of taste dysfunction.

Inflammation is initiated when Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are activated by inflammatory stimuli derived from pathogens, damaged tissues, or stress.15, 16 TLR signaling induces the expression of a large number of cytokines, including IFNs. As extracellular signaling proteins, cytokines orchestrate immune reactions by regulating the cellular activities, survival and death of many types of immune and non-immune cells.17, 18 How inflammation affects gustation remains to be understood. It is possible that activation of TLRs and IFN receptors may disrupt normal taste transduction or cell renewal in taste buds. In this study, we explore the possible role of TLR and IFN pathways in the onset of taste disorders.

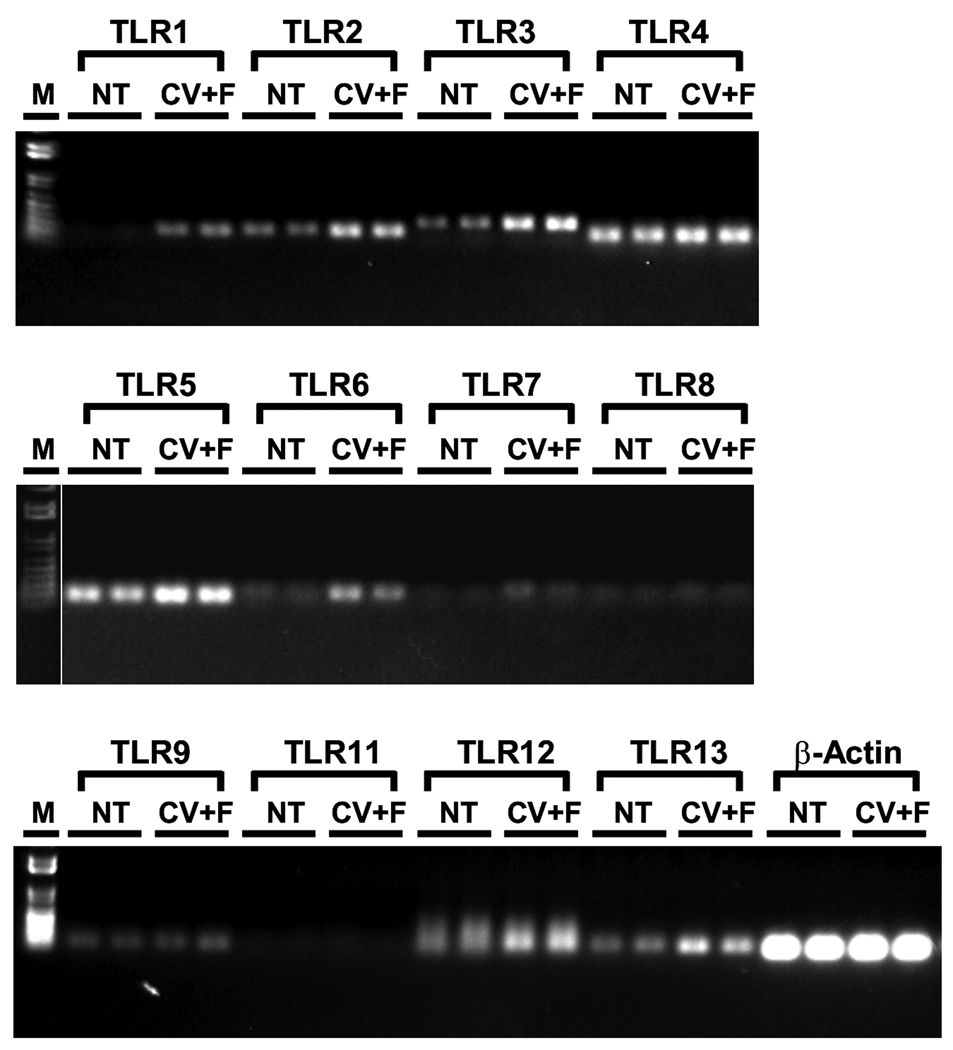

Expression of TLR receptors in taste bud cells

The TLR receptor family plays an essential role in the initiation of inflammation. Some of these receptors reside on the cell surface and recognize microbial membrane lipids and cell wall components or molecules released from damaged tissues while other TLRs are found in intracellular organelles and bind to microbial nucleic acids.15, 16 To investigate whether inflammatory agents can directly stimulate taste bud cells through TLRs, we examined the expression of these receptors in taste buds. RNAs were extracted from mouse taste epithelium and from non-gustatory lingual epithelium as a control, and reverse transcribed into cDNAs as described previously.19 PCR analyses were performed using gene-specific PCR primers derived from 12 known mouse Tlrs (Table 1). As shown in Figure 1, transcripts for 10 of these 12 genes: Tlrs 1-7, 9, 12, 13, were successfully amplified, and their identities were confirmed with DNA sequencing analysis. The other two Tlrs, Tlr 8 and 11, seemed to be absent in both taste and non-taste lingual epithelia. Among the ten expressed genes, Tlrs 1, 6 and 7 appeared to be selectively expressed in taste papillae while Tlrs 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 12 and 13 were more abundantly expressed in taste tissue than in the non-taste lingual epithelium.

Table 1.

RT-PCR primers.

| Gene Name |

GenBank Accession Number |

Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tlr1 | NM_030682 | CCCTACAGAAACGTCCTATAC | GCTCACATTCCTCAGATAATTG | 166 |

| Tlr2 | NM_011905 | ACCGAAACCTCAGACAAAGC | GAGGGAATAGAGGTGAAAGA | 178 |

| Tlr3 | NM_126166 | CTCTGTGCAGAAGATTCAAG | CCGACTCCAAATCTTCAAATG | 266 |

| Tlr4 | NM_021297 | TTCAGAACTTCAGTGGCTGG | GTTAGTCCAGAGAAACTTCC | 147 |

| Tlr5 | XM_977935 | AGGATGTTGGCTGGTTTCTC | CTAGGAAATGGTTGCTATGG | 110 |

| Tlr6 | NM_011604 | CCGTCAGTGCTGGAAATAGA | AGGGCGCAAACAAAGTGGAA | 136 |

| Tlr7 | NM_133211 | CACCAGACCTCTTGATTCCA | CACAAGGTAGAGTTTTAGGA | 148 |

| Tlr8 | NM_133212 | CGTTTTACCTTCCTTTGTCT | CTTCTGGAATAGTTCGCTTT | 125 |

| Tlr9 | NM_031178 | GAATCCTCCATCTCCCAACA | TCAGCTCACAGGGTAGGAAG | 131 |

| Tlr11 | NM_205819 | GTTTCTGGAGCCCCTTGATA | TGCAGTCCTTAATCTCTTTC | 174 |

| Tlr12 | NM_205823 | AACCCATTTCTCGGCACCAG | AATTCACATGCACCACCCCA | 175 |

| Tlr13 | NM_205820 | AGCAGAGTTCAGAATGAGTG | CAAAGCTGCTCCCATTCATC | 155 |

| β-Actin | NM_007393 | GATTACTGCTCTGGCTCCTA | ATCGTACTCCTGCTTGCTGA | 142 |

Figure 1.

Multiple TLR transcripts are expressed in taste epithelium. Shown here are the gel images of RT-PCR products for 12 currently known mouse TLRs as well as the positive control β-actin from nontaste lingual epithelium (NT) or from lingual epithelium containing circumvallate and foliate taste buds (CV+F). Transcripts for all TLRs except TLRs 8 and 11 were successfully amplified. M: 1 kb DNA ladder.

To verify the presence of these TLR receptor proteins in taste bud cells, we performed immuno-fluorescent staining with antibodies against TLRs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7.20–23 Figure 2 shows the immunostaining patterns of these antibodies on taste papillae sections. The specificity of the immunoreactivity was confirmed by the following control experiments: 1) omission of primary antibodies; and 2) preincubation of primary antibodies (anti-TLR2 and anti-TLR3) with antigenic blocking peptides. No specific immunoreactivity in taste buds was observed in these controls (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

TLR receptor proteins are localized to taste bud cells. Top two rows are the confocal images of immunostaining of taste tissue sections with antibodies against TLR1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-30000, raised against the antigenic peptide of amino acid residues 161–250 of human TLR1), TLR2 (Cell Signaling Technology, #2229, raised against the antigenic peptide of amino acid residues 179–203 of human TLR2), TLR3 (Cell Signaling Technology, #2253, raised against the antigenic peptide of amino acid residues 883-904 of human TLR3), TLR4 (eBioscience, #24–9048, raised against bacterially expressed recombinant human TLR4), TLR6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-5662, raised against an 18-amino acid peptide between residues 75–125 of mouse TLR6) and TLR7 (eBioscience, #14–9079, raised against a 14-amino acid peptide between residues 400–450 of mouse TLR7). The antibodies raised against human TLR1-4 cross-react with the corresponding mouse TLR. Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies were used except for TLR6 antibody, which was paired with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Bottom panels show the controls with primary antibody omitted or preincubated with antigenic peptides. Images were taken using a Leica (Nussloch, Germany) TCS SP2 spectral confocal microscope, which were then arranged and adjusted for contrast and brightness by using Photoshop v8 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

The immunostaining patterns indicated that the immunoreactivities to the antibodies of these TLRs, particularly, TLRs 2, 3, and 4, were much stronger in taste buds than in intergemmal epithelial cells (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Although at mRNA level, the expression of TLR4 in taste epithelium was only about two-fold higher than in nontaste epithelium (Figure 1 and quantitative PCR data not shown), the signal from TLR4 antibody staining was much brighter in taste buds than in surrounding nontaste epithelial cells, suggesting the possible post-transcriptional regulation. Another possible cause of this discrepancy may originate from the differences in sample preparation procedures: for immunostaining, the lingual tissue was immediately fixed, whereas for RNA preparation, lingual epithelia were peeled off from the rest of the tongue, which would inevitably cause tissue damage and may trigger an inflammatory response, possibly altering gene expression profiles in both taste and non-taste lingual epithelia. Therefore, immunostaining results are probably a more accurate representation of normal TLR expression in lingual tissues.

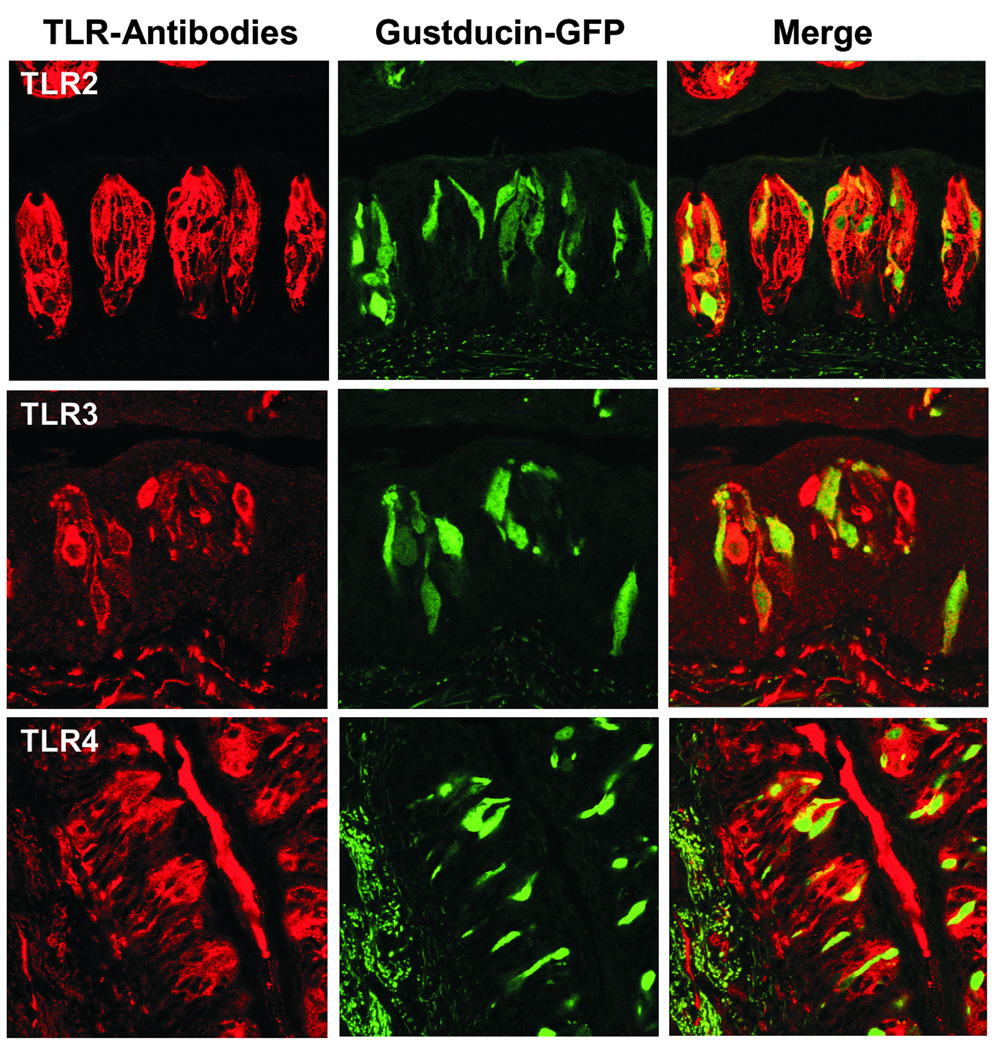

Figure 3.

Colocalization of TLRs 2, 3, and 4 with gustducin. Circumvallate sections from gustducin-GFP transgenic mice were immunostained with the same antibodies against TLRs 2, 3 and 4 as those described in Figure 2 legend. Cells positive for TLRs 2, 3, and 4 are shown in red (left panels). Gustducin-positive cells are represented by GFP (middle panels). Merged images show the colocalization of TLRs with gustducin (right panels).

To localize the TLRs to subsets of taste bud cells, we performed immunostaining with tissue sections prepared from transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the gustducin promoter (gustducin-GFP).24 As shown in Figure 3, most gustducin-positive cells were also positive for TLRs 2, 3, and 4, suggesting that these TLRs are expressed in gustducin-positive type II taste receptor cells. The staining patterns of the three TLR antibodies differed with fewer TLR3-expressing cells than TLR2- or TLR4-positive taste bud cells. These distinct distribution patterns may be related to the receptors’ unique functions: TLR3 binds to viral dsRNA whereas TLR2 and TLR4 recognize bacterial or fungal pathogens. Activation of TLRs by bacterial cell wall components, fungal cell membrane lipids or viral nucleic acids initiates intracellular signaling cascades, which eventually lead to the activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), IFN regulatory factor (IRF) −3, and −7 and the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IFNs.15, 16

In addition to immune cells, many other types of cells, such as various epithelial cells and neurons, express TLRs.25, 26 Interestingly, enteroendocrine cells, which express taste receptors and taste signaling components, have also been found to express TLR1, TLR2, TLR4 and TLR6.20 These TLRs can detect microbial components and likely play a role in initiating inflammatory responses.20

Activities of the IFN signaling pathways in taste buds

IFNs are one of the major groups of cytokines that are highly induced during viral and bacterial infections and in autoimmune conditions.27, 28 Medicinal use of IFN-α for cancer or viral infection is often accompanied by subsequent taste disorders.29–31 To investigate whether IFNs are involved in the onset of taste deficits, we studied the expression of types I and II IFN signaling pathways, again in taste buds-containing lingual epithelium. RT-PCR results demonstrated the expression of types I and II IFN receptors, Janus kinases JAK1, JAK2 and TYK2, and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins STAT1 and STAT2 in taste epithelium.19 More importantly, quantitative real-time RT-PCR showed that the ligand-binding subunits of types I or II IFN receptors, IFNAR2 and IFNGR1, are preferentially expressed in taste epithelium compared with the surrounding nongustatory epithelium. Immunofluorescent staining using an antibody against IFNGR1, the receptor subunit for type II IFN (IFN-γ), confirmed its expression in taste bud cells. Immuno-colocalization studies with antibodies against IFNGR1 and the taste cell type markers neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and α-gustducin revealed that IFNGR1 is expressed in most NCAM-positive type III cells and about half of gustducin-positive type II cells. Treatment of cultured lingual epithelium with IFN-α or IFN-γ rapidly stimulated phosphorylation of STAT1 transcription factor in taste papillae. Inflammation induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS or poly (I:C), a synthetic dsRNA, into mice, dramatically down-regulated the expression of a cellular activity-related gene, c-fos, but up-regulated the expression of several IFN-inducible genes in taste buds.19 Among these up-regulated genes is the IFN-regulatory factor-1 (Irf-1), which plays a critical role in initiating apoptosis.32 Consistent with this result, administration of IFN-α or IFN-γ in mice significantly augmented apoptosis in taste buds as revealed by cleaved caspase-3 immunostaining and cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) Western blotting, two commonly used methods for detecting apoptosis.33, 34

Collectively, these findings suggest that taste bud cells express cytokine signaling pathways and that inflammation may affect taste function through these pathways. Inflammatory cytokines, such as IFNs, can trigger apoptotic cell death and therefore may cause abnormal cell turnover in taste buds. The actions of these cytokines may result in the net losses of taste bud cells and/or skewing the representation of different types of taste cells and ultimately lead to the development of taste dysfunction.

Conclusions

Inflammation has been suggested as an underlying cause of taste disorders. However, the molecular and cellular mechanisms remain to be determined. Here we investigate the TLR and IFN signaling pathways in taste buds. Unlike the surrounding non-gustatory lingual epithelium, taste bud cells are directly exposed to the external environment at the taste pore. Stimulation of the TLRs by bacterial and viral pathogens in the oral cavity can activate their downstream signaling pathways and alters gene expression, including the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IFNs in taste buds. Activation of IFN receptors by local or circulating IFNs also triggers signaling cascades and further changes gene expression in taste cells. TLR and IFN pathways may act collaboratively in combating microbial pathogens. As a result, however, the normal taste transduction and cell turnover in taste buds can be adversely affected, contributing to the development of taste dysfunction.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants DC007974 (HW) and DC007487 (LH) and a National Science Foundation Grant DBJ-0216310 (N. Rawson).

References

- 1.Heald AE, Schiffman SS. Taste and smell. Neglected senses that contribute to the malnutrition of AIDS. N. C. Med. J. 1997;58:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherry WV. Taste alterations among patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:73–77. doi: 10.1188/02.CJON.73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wickham RS, Rehwaldt M, Kefer C, et al. Taste changes experienced by patients receiving chemotherapy. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 1999;26:697–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pribitkin E, Rosenthal MD, Cowart BJ. Prevalence and causes of severe taste loss in a chemosensory clinic population. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2003;112:971–978. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henkin RI, Larson AL, Powell RD. Hypogeusia, dysgeusia, hyposmia, and dysosmia following influenza-like infection. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1975;84:672–682. doi: 10.1177/000348947508400519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodspeed RB, Gent JF, Catalanotto FA. Chemosensory dysfunction. Clinical evaluation results from a taste and smell clinic. Postgraduate Med. 1987;81:251–260. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1987.11699680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen MM, Leopold DA. Disorders of smell and taste. Med. Clin. North Am. 1999;83:57–74. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham CS, Graham BG, Bartlett JA, et al. Taste and smell losses in HIV infected patients. Physiol. Behav. 1995;58:287–293. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00049-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith FR, Henkin RI, Dell RB. Disordered gustatory acuity in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:568–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiffenbach JM, Schwartz LK, Atkinson JC, et al. Taste performance in Sjögren's syndrome. Physiol. Behav. 1995;57:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00211-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez FE, Cassís-Nosthas L, Morales-de-León JC, et al. Detection and recognition thresholds to the 4 basic tastes in Mexican patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;58:629–636. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell SM, Montanaro A, Bardana EJ. Head and neck manifestations of autoimmune disease. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 1983;4:187–216. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(83)80042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakic B, Szechtman H, Braciak T, et al. Reduced preference for sucrose in autoimmune mice: a possible role of interleukin-6. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwant A, Sakić B. Behavioral effects of infection with interferon-gamma adenovector. Behav. Brain Res. 2004;151:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brikos C, O'Neill LA. Signalling of toll-like receptors. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;183:21–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72167-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kishimoto T, Taga T, Akira S. Cytokine signal transduction. Cell. 1994;76:253–262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ihle JN. Cytokine receptor signalling. Nature. 1995;377:591–594. doi: 10.1038/377591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Zhou M, Brand J, et al. Inflammation activates the interferon signaling pathways in taste bud cells. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10703–10713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3102-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogunovic M, Dave SH, Tilstra JS, et al. Enteroendocrine cells express functional Toll-like receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1770–G1783. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00249.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shuto T, Kato K, Mori Y, et al. Membrane-anchored CD14 is required for LPS-induced TLR4 endocytosis in TLR4/MD-2/CD14 overexpressing CHO cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:1402–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu H, Wang H, Xiong W, et al. Expression patterns and functions of toll-like receptors in mouse sertoli cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4402–4412. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triantafilou M, Gamper FG, Haston RM, et al. Membrane sorting of toll-like receptor (TLR)-2/6 and TLR2/1 heterodimers at the cell surface determines heterotypic associations with CD36 and intracellular targeting. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31002–31011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang L, Shanker YG, Dubauskaite J, et al. Ggamma13 colocalizes with gustducin in taste receptor cells and mediates IP3 responses to bitter denatonium. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/15981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uehara A, Fujimoto Y, Fukase K, et al. Various human epithelial cells express functional Toll-like receptors, NOD1 and NOD2 to produce anti-microbial peptides, but not proinflammatory cytokines. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:3100–3111. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen PH, Holm TH, Owens T. Toll-like receptors in brain development and homeostasis. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:pe47. doi: 10.1126/stke.4022007pe47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalvakolanu DV. Alternate interferon signaling pathways. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2003;100:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theofilopoulos AN, Baccala R, Beutler B, et al. Type I Interferons in Immunity and Autoimmunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:307–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P, Nordman E, Toivanen A. Combined interferon and vinblastine treatment of advanced melanoma: evaluation of the treatment results and the effects of the treatment on immunological functions. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1989;28:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00204991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones GJ, Itri LM. Safety and tolerance of recombinant interferon alfa-2a (Roferon-A) in cancer patients. Cancer. 1986;57:1709–1715. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860415)57:8+<1709::aid-cncr2820571315>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdollahi M, Radfar M. A review of drug-induced oral reactions. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2003;4:010–031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka N, Ishihara M, Kitagawa M, et al. Cellular commitment to oncogene-induced transformation or apoptosis is dependent on the transcription factor IRF-1. Cell. 1994;77:829–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholson DW, Ali A, Thornberry NA, et al. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 1995;376:37–43. doi: 10.1038/376037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garnier P, Ying W, Swanson RA. Ischemic preconditioning by caspase cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7967–7973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-07967.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]