Abstract

Objective

Our previous studies revealed upregulation of stanniocalcin-1 (STC1) in cardiac vessels in dilated cardiomyopathy. However, the functional significance of STC1 is unknown. The objective of this study was to determine the effects of STC1 on TNF-α-induced monolayer permeability of human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs).

Methods and Results

Cells were pretreated with STC1 for 30 minutes followed by treatment with TNF-α (2 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Monolayer permeability was studied using a trans-well system. STC1 pretreatment significantly blocked TNF-α-induced monolayer permeability in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. STC1 effectively blocked TNF-α-induced downregulation of endothelial tight junction proteins zonula occluden-1 and claudin-1 at both mRNA and protein levels. STC1 also significantly decreased TNF-α-induced superoxide anion production. The inhibitory effect of STC1 was specific to TNF-α, as it failed to inhibit VEGF-induced endothelial permeability. Furthermore, STC1 partially blocked NF-κB and JNK activation in TNF-α-treated endothelial cells. JNK inhibitor and antioxidant also effectively blocked TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation and monolayer permeability in HCAECs.

Conclusions

STC1 maintains endothelial permeability in TNF-α-treated HCAECs through preservation of tight junction protein expression, suppression of superoxide anion production and inhibition of the activation of NFκB and JNK, suggesting an important role for STC1 in regulating endothelial functions during cardiovascular inflammation.

Keywords: stanniocalcin-1, TNF-α, endothelial cell, permeability, superoxide anion

Introduction

Stanniocalcin 1 (STC1) is a 25-kDa disulfide-linked homodimeric glycoprotein, which was originally identified as a secretory hormone of the corpuscles of Stannius, an endocrine gland unique to bony fish.1 The mammalian homolog of STC1 has been found in many species including humans, rats, and mice.2,3 Human STC1 is encoded by a single copy gene located on chromosome 8p11.2–p21 and comprises four exons that encode 247 amino acids with 11 cysteine residues.2,3 Human and mouse STC1 proteins have 98% amino acid identity and share 73% overall sequence homology to fish STC.2 Unlike the localized expression of STC1 in fish, mammalian STC1 is not detected in the blood and is expressed in many organs including the kidneys, intestine, heart, thyroid, lung, placenta, brain and bone,4,5 suggesting a paracrine rather than an endocrine role for STC1 in mammals. The primary function of STC in fish is to prevent hypercalcemia6 by inhibiting calcium influx through the gills and gut and stimulating phosphate reabsorption by the kidneys7 Similarly, in rodents, STC1 reduces the intestinal uptake of calcium while enhancing that of phosphate.8 Furthermore, this gene seems to play diverse roles in numerous developmental, physiological and pathological processes including cancer, pregnancy, lactation, angiogenesis, organogenesis, cerebral ischemia, and hypertonic stress.9 Studies also indicate that STC1 modulates inflammation. For examples, STC1 inhibited chemotaxis of mouse macrophages and human monoblasts in response to monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha (SDF1-α)10 and decreased transmigration of macrophages and T-lymphocytes across quiescent or interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β)-activated human endothelial cells.11 Despite the growing body of knowledge about STC1, little is known about its effects on the vascular system and how it might affect endothelial barrier function during inflammation.

The endothelial barrier is established and maintained mainly by endothelium-endothelium junction structures including adherens junctions, tight junctions (TJ), desmosomes and gap junctions. Cohesive interactions between TJ molecules localized on apposing strands occlude the lateral intercellular space, thus restricting the paracellular diffusion of solutes. TJ are composed of integral membrane proteins including occludin and claudins; junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A); and intracellular proteins such as zonula occluden-1 (ZO-1) and cingulin.12 Increased vascular permeability is a common feature in many pathological conditions such as obstruction of airways during asthma and related pulmonary disorders,13 circulatory collapse in sepsis, cancer growth and metastatic spread,14 and many inflammatory conditions. Increased vascular permeability is also associated with the development of atherosclerosis.15 We have previously shown increased expression of STC1 in cardiac vessels and cardiomyocytes of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.16 The expression of STC1 mRNA in endothelial cells, and the remarkable increase in the expression of STC1 protein in blood vessels of the failing heart suggested an important role for this protein in the vascular system. Studies from our laboratories also suggest that STC1 suppresses inflammation;11,17 however, it is unknown whether STC1 plays a role in endothelial barrier function, particularly during inflammation. Since heart failure and atheresoclerosis are characterized by increased oxidative stress18 and upregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6,19 we hypothesized that STC1 may inhibit cyctokine-induced endothelial permeability and thus may maintain endothelial integrity in the failing heart and atherosclerotic vessels. In this study, we examined the effects of STC1 on TNF-α-induced permeability of human coronary artery endothelial cell (HCAEC) monolayer and determined the effects of STC1 on cytokine-induced changes in the expression of TJ molecules; generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS); activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs); and transcription factor NF-kB. This study demonstrates a new role for STC1 in the regulation of inflammation and endothelial functions.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

Recombinant human STC1 protein and rabbit anti-human STC1 antibodies were kindly provided by Dr. Henrik Olsen, Human Genome Sciences (Rockville, MD).20 STC1 protein was expressed in a baculovirus expression system and is greater than 90% pure.21 Endotoxin levels of the STC1 preparation are no detectable.21 Detail information about materials and methods is provided in the online supplementary materials.

Endothelial Permeability

Permeability indicated by paracellular influx across the HCAEC monolayer was studied in a Coaster Transwell system. They were pre-treated with different concentrations of STC1 (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 ng/mL) for 30 minutes and then treated with TNF-α (2 ng/mL) or vehicle for up to 48 hours. In separate experiments, cells were treated with anti-STC1 antibody, VEGF, nifedipine, JNK inhibitor (SP600125) or SOD mimetic Mn (III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP).22 After treatment, equal amount of Texas-Red-labeled dextran tracer was added to the upper chamber. The amount of tracer penetrating through the cell monolayer into the lower chamber was measured by a fluorometer.

Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis

The mRNA levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1 were determined by real-time PCR as described in our previous publication.23 Expression for each target gene in each sample was normalized to β-actin.

Western Blot

Total cell extract, nuclear extract or cytoplasmic extract of HCACEs was prepared. Equal amounts of proteins (50 μg) were loaded onto SDS PAGE gel for electrophoresis, and proteins were transblotted overnight at 4°C onto Hybond-P PVDF membrane, probed with the respective primary antibodies against human ZO-1, claudin-1, p-IκBα, total IκBα, NF-κB p56, and β-actin, respectively.

Flow Cytometery

The FITC-conjugated primary antibody against ZO-1 and non-conjugated primary antibody against claudin-1 (1:200) were used to detect protein levels, respectively, analyzed by flow cytometry. The oxidative fluorescent dye dihydroethidium (DHE) was used to evaluate the production of intracellular superoxide anion. In the presence of superoxide anion, DHE is oxidized to ethidium bromide (EtBr), which is trapped by intercalating with the DNA and emits red fluorescence. Thus, the amount of EtBr correlates well with the level of cellular superoxide anion.

Bio-Plex Luminux Assay

Bio-Plex phosphoprotein and total target assay kits were used on a Luminex multiplex system (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer's instructions. The kits can detect the amount of phosphorylated and total JNK and IκBα in a small amount of cell lysates. Results were presented as the ratio of phosphorylated versus total target proteins.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SD. Comparisons were made using the Student's t-test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

STC1 Specifically Blocks TNF-α-Induced Endothelial Monolayer Permeability in HCAECs

To determine whether STC1 could protect endothelial cells from cytokine-mediated effects, STC1 was added to TNF-α-treated HCAECs and endothelial permeability was analyzed using the Transwell system and Texas-Red-labeled dextran tracer. As shown in Figure 1A and B, treatment of HCAEC monolayer with TNF-α (2 ng/mL) for 24 hours significantly increased endothelial permeability by 55% as compared with untreated cells (n=4, P<0.05). Within the same system, co-treatment with TNF-α and STC1 (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 ng/mL) blocked TNF-α-induced increase in permeability of HCAECs, in a dose-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 12.5 ng/ml STC1, and complete inhibition of TNF-α-induced changes in endothelial permeability by STC1 at a concentration greater than 25 ng/ml (n=4, P<0.05). In the control experiment, STC1 alone had no effects on endothelial permeability. Thus, STC1 effectively blocks TNF-α-induced EC permeability.

Figure 1.

Effects of STC1 on TNF-α-induced monolayer permeability in HCAECs. A and B. Concentration-dependent study. HCAECs were treated with TNF-α and increasing concentrations of STC1 for 24 hours. Endothelial permeability was analyzed using the Transwell system and Texas-Red-labeled dextran tracer. C. Time course study. D. Antibody blocking study. n=4. *P<0.05.

As a time course study, co-treatment of HCAECs with STC1 (50 ng/mL) and TNF-α effectively blocked TNF-α-induced increase in permeability for extended periods (12, 24 and 48 hours) (Figure 1C). In a separate experiment, we examined the effect of STC1 (50 ng/ml) on TNF-α-induced changes in endothelial permeability at earlier time points (30, 90, 120, and 240 minutes). As shown in Figure I, TNF-α (2 ng/ml) did not increase endothelial permeability at 30, 90, and 120 minutes, while it significantly increased endothelial permeability by 66% at 240 minutes compared with untreated controls (n=4, P<0.05). STC1 could significantly block TNF-α-induced endothelial permeability by 27% at 240 minutes compared with TNF-α-treated groups (n=4, P<0.05). Thus, the effects of STC1 on endothelium permeability occur within 3 hours and precede TNF-α-induced changes.

To further demonstrate the specificity of STC1 effect on HCAECs, a specific neutralizing antibody against STC1 was used. Indeed, anti-STC1 antibody could block the effects of STC1 on TNF-α-treated HCAECs in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1D, n=4, P<0.05). Isotype control IgG or heat-inactivated anti-STC1 antibody had no effect on TNF-α–induced rise in permeability of HCAEC monolayer.

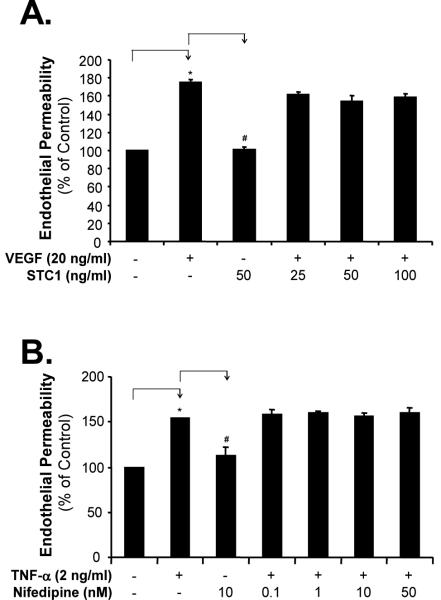

STC1 Does Not Block VEGF-Induced Endothelial Monolayer Permeability in HCAECs

Since TNF-α and VEGF increase endothelial permeability through different mechanisms,24,25 we determined whether STC1 could affect VEGF-induced changes in endothelial permeability. Treatment of HCAECs with VEGF (20 ng/mL) for 24 hours significantly increased monolayer cell permeability compared with vehicle-treated controls, and addition of STC1 at concentrations that effectively blocked TNF-α-induced increase in endothelial permeability (25, 50, and 100 ng/mL) failed to block VEGF-induced increase in HCAEC monolayer permeability (Figure 2A). These data indicate that STC1 specifically inhibits TNF-α-induced changes in endothelial permeability, but not VEGF-induced signaling pathways regulating endothelial permeability.

Figure 2.

Effects of STC1 and nifedipine on monolayer permeability in HCAECs. A. VEGF-induced monolayer permeability. HCAECs were treated with VEGF (20 ng/mL) with or without STC1 for 24 hours. B. Effect of nifedipine. HCAECs were treated with TNF-α (2 ng/mL) with or without nifedipine for 24 hours. n=4. *P<0.05.

Calcium Channel Blocker Nifedinine Does Not Block TNF-α-Induced HCAEC Monolayer Permeability

Since STC1 is an L-type calcium channel blocker,1,2 we determined whether L-type calcium channels could be involved in TNF-α-induced changes in endothelial permeability. As shown above, TNF-α induced a significant increase in HCAECs monolayer permeability. However, increasing concentrations of an L-type calcium channel blocker nifedipine (0.1, 1, 10, and 50 nM) had no effects on TNF-α-induced permeability increase in HCAECs (Figure 2B). These data indicate that TNF-α-induced changes in endothelial permeability are not L-type calcium channel-mediated; and that STC1 modulates endothelial permeability through a mechanism which is L-type calcium channel independent.

STC1 Blocks TNF-α-Induced Down-Regulation of ZO-1 and Claudin-1 in HCAECs

Since the mechanism of TNF-α-induced endothelial permeability involves the destruction of endothelial junction structures,26,27 we determined whether STC1 could affect the expression of junction molecules in TNF-α-treated cells. The mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1 were analyzed by real time PCR, Western blot and flow cytometery, respectively. As shown in Figure 3A, TNF-α (2 ng/ml) treatment for 24 hours significantly reduced mRNA levels of ZO-1 by 34% and claudin-1 by 57% compared with untreated groups (n=4, P<0.05) and STC1 (25, 50 and 100 ng/ml) significantly blocked TNF-α-induced decrease in ZO-1 and claudin-1 mRNA levels compared with TNF-α-treated groups (n=4, P<0.05). Protein levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1 were also decreased substantially in TNF-α-treated cells, while STC1 effectively blocked the effect of TNF-α on ZO-1 and claudin-1 proteins expression in HCAECs (Figure 3B and Figure II).

Figure 3.

Effects of STC1 on TNF-α-induced downregulation of ZO-1 and claudin-1 in HCAECs. HCAECs were treated with TNF-α (2 ng/mL) with or without STC1 for 24 hours. A. The mRNA levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1 were analyzed by real time PCR. n=4. *P<0.05. B. The protein levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1 analyzed with Western blot.

STC1 Blocks TNF-α-Induced Superoxide Anion Production in HCAECs

Since oxidative stress is involved in TNF-α-induced increase in endothelial permeability, we determined whether STC1 could inhibit TNF-α-induced superoxide anion production in HCAECs. Cellular superoxide anion levels were determined by fluorescent dye DHE staining and flow cytometery analysis. There were 30% of DHE-positive cells in untreated controls, compared with 63% in TNF-α-treated cells (Figure 4). TNF-α and STC1 co-treatment decreased DHE staining from 63% to 43%. These data demonstrate that STC1 can effectively inhibit TNF-α-induced oxidative stress in HCAECs.

Figure 4.

Effects of STC1 on TNF-α-induced superoxide anion production in HCAECs. HCAECs were treated with TNF-α (2 ng/mL) with or without STC1 (50 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Cellular superoxide anion levels were determined by fluorescent dye DHE staining and flow cytometery analysis.

STC1 Partially Blocks TNF-α-Induced Activation of JNK and NF-κB in HCAECs

Since the effect of TNF-α is mediated through signal transduction pathways including MAPK JNK and transcription factor NF-κB,28 we determined whether STC1 could inhibit TNF-α-induced activation of JNK and NF-κB in HCAECs. JNK activation was directly measured as phospho-JNK/total JNK by Bio-Plex luminex immunoassay. NF-κB activation was studied indirectly by measuring the activity of IκBα an inhibitor NF-κB, determined as phospho-IκBα/total IκBα.29 HCAECs were treated with TNF-α in the presence or absence of STC1 for increasing times (from 1 to 120 minutes). TNF-α treatment substantially increased JNK phosphoarylation, which peaked at 90 minutes (Figure 5A), and IκBα phosphorylation, which peaked at 20 minutes (Figure 5B). Addition of STC1 partially inhibited TNF-α-induced phosphorylation of both JNK and IκBα in HCAECs. Furthermore, we performed Western blot analysis to determine cytoplasmic IκBα phosphorylation and nuclear NF-κB levels. As shown in Figure 5C, TNF-α (2 ng/ml) treatment for 20 minutes increased cytoplasmic IκBα phosphorylation, while STC1 (50 ng/ml), JNK inhibitor SP600125 (10 μM) or SOD mimetic MnTBAP (3 μM) effectively blocked TNF-α induced cytoplasmic IκBα phosphorylation compared with TNF-α-treated groups. Concomitantly, TNF-α treatment for 20 min, but not 1 min, increased nuclear NF-κB (p65) levels, while STC1, SP600125 or MnTBAP effectively blocked TNF-α-induced increase in nuclear NF-κB (p65) levels compared with TNF-α treated groups. These data suggest that oxidative stress and JNK activation are responsible for TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation. STC1 may inhibit TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB through suppression of superoxide generation and inhibition of JNK.

Figure 5.

Effects of STC1 on TNF-α-induced phosphorylation of JNK and IκBα and nuclear NF-κB levels in HCAECs. HCAECs were treated with TNF-α with or without STC1, JNK inhibitor (SP600125), or antioxidant (MnTBAP) for different time points. A and B. The phosphorylation of JNK and IκBα was determined by Bio-Plex luminex immunoassay. C. Cytoplasmic IκBα and nuclear NF-κB levels were determined with Westen blot analysis. D. Effects of JNK inhibitor and antioxidant on TNF-α-induced monolayer permeability. n=4, *P<0.05.

JNK Inhibitor and Antioxidant Block TNF-α-Induced HCAEC Monolayer Permeability

We performed experiments of endothelial permeability with TNF-α, STC1, JNK inhibitor (SP600125), and MnTBAP. As shown in Figure 5D, SP600125 (10 μM) or MnTBAP (3 μM) significantly blocked TNF-α-induced endothelial permeability compared with TNF-α alone-treated cells (n=4, P<0.05). These data suggest oxidative stress and JNK activation are directly responsible for the TNF-α-induced endothelial permeability. STC1 may inhibit TNF-α-induced increase in endothelial permeability through suppression of superoxide generation and inhibition of JNK.

Discussion

It is well known that TNF-α can induce endothelial permeability in many inflammatory conditions including cardiovascular disease and tumor progression. However, it is largely unknown whether naturally occurring molecules could inhibit the effects of TNF-α during inflammation. In the present study, we demonstrate a novel function of STC1 which can inhibit TNF-α-induced increase in endothelial permeability in HCAECs. STC1 specifically inhibits a series of TNF-α-induced events in HCAECs including the attenuation of tight junction molecules ZO-1 and claudin-1, over-production of superoxide anion, and activation of JNK and NF-κB in HCAECs.

Endothelial cells form the main physical barrier for blood constituents. They also actively control the extravasation of blood components to the surrounding tissues. In many inflammatory conditions, endothelial permeability increases in response to inflammatory cytokines and growth factors. Several edema-producing agents, including thrombin, VEGF, histamine, IL-1, interferon-γ and TNF-α stimulate protein tyrosine phosphorylation and other signaling pathways in endothelial cells to increase permeability.30 Increased endothelial permeability to circulating macromolecules is an early and important event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.31 In the current study, we have confirmed that TNF-α significantly increases HCAEC monolayer permeability using the Transwell system, a well characterized and accepted simple and reliable model for in vitro endothelial cell permeability assay. More importantly, STC1 can effectively inhibit the increase in endothelial permeability in response to TNF-α treatment in the same model. Inhibitory action of STC1 is very potent since a very small concentration of STC1 (25 ng/mL) could completely block the effect of TNF-α in HCAECs. These novel findings identify a new role for STC1 in stabilizing the endothelial barrier during inflammation. These discoveries are complementary to recent observations suggesting that STC1 inhibits transendothelial migration of macrophages and T-lymphocytes through quiescent or IL-1β-activated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro.11 In addition, STC1 regulates gene expression in cultured endothelial cells, and is detected on the apical surface of endothelial cells in vivo. We previously showed increased expression of STC1 in cardiac vessels and cardiomyocytes of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.16 The increase in STC1 protein expression in blood vessels of the failing heart suggested an important role for this protein in heart failure. Heart failure is characterized by increased oxidative stress18 and upregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6.19 Upregulated expression of TNF-α and other cytokines in the failing heart is expected to induce ROS and activate JNK and NF-kB in endothelial cells, and thus affect endothelial barrier. Our studies strongly suggest that STC1 plays a critical role in regulating endothelial function under normal conditions and during inflammation including heart failure and atherosclerosis, and could advance our understanding of anti-inflammation pathways, which may have therapeutic value in many inflammatory diseases.

Specificity of the inhibitory effect of STC1 on TNF-α-induced endothelial permeability is carefully addressed in the current study. Effects of STC1 are concentation- and time-dependent. Specific antibodies against STC1, but not other control antibodies, could effectively block STC1 effect on HCAECs. Although both TNF-α and VEGF can induce endothelial permeability in HCAECs, they act through different receptors and signal pathways.24,25 To determine whether STC1 could be a specific inhibitor for TNF-α, we performed additional experiments with STC1 and VEGF using the Transwell system. Interestingly, STC1 fails to inhibit VEGF-induced increase in monolayer permeability in HCAECs, indicating that the inhibitory effect of STC1 is specific to TNF-α and possibly other cytokines. Are the effects of STC1 on endothelial permeability related to changes in calcium homeostasis? Recent data from our lab suggest that STC1 inhibits L-type calcium channel in cardiomyocytes,16 and diminishes intracellular calcium in cultured murine macrophages.17 Hence, we examined whether STC1 could modulate the effect of TNF-α through inhibition of calcium channels. Notably, increasing concentrations of the L-type calcium channel inhibitor nifedinine failed to block TNF-α-induced increase in endothelial permeability in HCAECs. These important data indicate that the inhibitory effects of STC1 on TNF-α-induced changes in endothelial permeability are independent of L-type calcium channels. Furthermore, we have also shown STC1 to regulate the expression of many genes in human endothelial cells.11 Collectively, these data indicate that STC1 plays a protective role in regulating endothelial cell functions.

Endothelial tight junctions consist of claudins, occludins and junctional adhesion molecules that are anchored in the membranes of two adjacent cells. Tight junction membrane proteins interact with scaffold proteins (e.g., ZO-1) to connect them with various signal transduction and transcriptional pathways involved in the regulation of tight junction function. It is well documented that TNF-α can down regulate several tight junction molecules.32 In the current study, we have confirmed that TNF-α significantly decreased the mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1 in HCAECs, which could contribute to the increase in endothelial permeability. Importantly, STC1 effectively blocks TNF-α-induced downregulation of ZO-1 and claudin-1 at both mRNA and protein levels.

Oxidative stress is an important factor which can increase endothelial permeability. ROS such as superoxide anion (·O 2-) contribute to endothelial barrier dysfunction in response to TNF-α.33 ROS are known to quench NO.34 Thus, inhibition of NO pathway can potentiate agonist-induced increases in vascular permeability or increase basal microvascular permeability.35 ROS can directly activate MAPKs and transcription factor NF-κB, which regulate the expression of many genes.36 In the current study, we have demonstrated that TNF-α significantly increases the production of superoxide anion in HCAECs, while STC1 effectively blocks this effect of TNF-α. These data are important and could explain the molecular mechanisms of STC1 inhibitory action on TNF-α-induced endothelial dysfunction. Indeed, STC1 significantly inhibits TNF-α-induced activation of JNK and NF-κB in HCAECs, thereby regulating the expression of ZO-1 and claudin-1. Accordingly, JNK inhibitor and antioxidant can effectively block TNF-α-induced NK-κB activation and endothelial permeability in HCAECs.

TNF-α is expressed as 24 kDa membrane bound protein that is proteolytically cleaved into its 17 kDa soluble form.37 TNF-α in its soluble, trimerized form binds to two receptors, TNFR1 (p55) and TNFR2 (p75). Human endothelial cells express both of these receptors.38 Binding of TNF-α to TNFR1 or TNFR2 induces receptor oligomerization and recruitment of several downstream adaptor and signaling proteins to their cytoplasmicdomains.39 It is not clear whether STC1 could act on the TNF-α receptors or upstream signaling molecules to block TNF-α activities. Further investigation in this regard is warranted.

In summary, human STC1 has diverse roles in developmental, physiological and pathological conditions. In the current study, we demonstrate, for first time, that STC1 can counteract the effect of TNF-α on endothelial permeability. STC1 inhibits TNF-α-induced signaling pathways including oxidative stress, and the activation of MAPK JNK and transcriptional factor NF-κB. This action of STC1 does not appear to be mediated through changes in L-type calcium channel conductance in human endothelial cells. This study suggests that STC1 is actively involved in the inflammation process as an effective inhibitor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding This work is partially supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (Chen: HL65916, HL72716, and EB-002436; Yao: DE15543; and Sheikh-Hamad: O'Brien Kidney Center grant DK064233-01 and DK062828).

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

References

- 1.Wagner GF, Hampong M, Park CM, Copp DH. Purification, characterization, and bioassay of teleocalcin, a glycoprotein from salmon corpuscles of Stannius. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1986;63:481–491. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(86)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang AC, Janosi J, Hulsbeek M, de Jong D, Jeffrey KJ, Noble JR, Reddel RR. A novel human cDNA highly homologous to the fish hormone stanniocalcin. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995;112:241–247. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varghese R, Wong CK, Deol H, Wagner GF, DiMattia GE. Comparative analysis of mammalian stanniocalcin genes. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4714–4725. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.11.6313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worthington RA, Brown L, Jellinek D, Chang AC, Reddel RR, Hambly BD, Barden JA. Expression and localisation of stanniocalcin 1 in rat bladder, kidney and ovary. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:2071–2076. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990701)20:10<2071::AID-ELPS2071>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang KZ, Westberg JA, Paetau A, von Boguslawsky K, Lindsberg P, Erlander M, Guo H, Su J, Olsen HS, Andersson LC. High expression of stanniocalcin in differentiated brain neurons. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:439–445. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65587-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner GF, Milliken C, Friesen HG, Copp DH. Studies on the regulation and characterization of plasma stanniocalcin in rainbow trout. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991;79:129–138. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu M, Wagner GF, Renfro JL. Stanniocalcin stimulates phosphate reabsorption by flounder renal proximal tubule in primary culture. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R1356–R1362. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen KL, Tavernini MM, Yachimec C, Mendrick DL, Alfonso PJ, Buergin M, Olsen HS, Antonaccio MJ, Thomson AB, Fedorak RN. Stanniocalcin: a novel protein regulating calcium and phosphate transport across mammalian intestine. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G96–G102. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.1.G96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang AC, Jellinek DA, Reddel RR. Mammalian stanniocalcins and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:359–373. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanellis J, Bick R, Garcia G, Truong L, Tsao CC, Etemadmoghadam Poindexter B, Feng L, Johnsonn RJ, Sheikh-Hamad D. tanniocalcin-1, an inhibitor of macrophage chemotaxis and chemokinesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;286:F356–F362. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00138.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakraborty A, Brooks H, Zhang P, Smith W, McReynolds MR, Hoying JB, Bick R, Truong L, Poindexter B, Lan H, Elbjeirami W, Sheikh-Hamad D. Stanniocalcin-1 regulates endothelial gene expression and modulates transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F895–F904. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00219.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bazzoni G. Endothelial tight junctions: permeable barriers of the vessel wall. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groeneveld AB. Vascular pharmacology of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;39:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald DM, Baluk P. Significance of blood vessel leakiness in cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5381–5385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen LB. Transfer of low density lipoprotein into the arterial wall and risk of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1996;123:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh-Hamad D, Bick R, Wu GY, Christensen BM, Razeghi P, Poindexter B, Taegtmeyer H, Wamsley A, Padda R, Entman M, Nielsen S, Youker K. Stanniocalcin-1 is a naturally occurring L-channel inhibitor in cardiomyocytes: relevance to human heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H442–H448. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01071.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanellis J, Bick R, Garcia G, Truong L, Tsao CC, Etemadmoghadam D, Poindexter B, Feng L, Johnson RJ, Sheikh-Hamad D. Stanniocalcin-1, an inhibitor of macrophage chemotaxis and chemokinesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F356–F362. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00138.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sam F, Kerstetter DL, Pimental DR, Mulukutla S, Tabaee A, Bristow MR, Colucci WS, Sawyer DB. Increased reactive oxygen species production and functional alterations in antioxidant enzymes in human failing myocardium. J Card Fail. 2005;11:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumgarten G, Knuefermann P, Mann DL. Cytokines as emerging targets in the treatment of heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:216–223. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen HS, Cepeda MA, Zhang QQ, Rosen CA, Vozzolo BL. Human stanniocalcin: a possible hormonal regulator of mineral metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1792–1796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Alfonso P, Thotakura NR, Su J, Buergin M, Parmelee D, Collins AW, Oelkuct M, Gaffney S, Gentz S, Radman DP, Wagner GF, Gentz R. Expression, purification, and bioassay of human stanniocalcin from baculovirus-infected insect cells and recombinant CHO cells. Protein Expr Purif. 1998;12:390–398. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuzzocrea S, Costantino G, Mazzon E, De Sarro A, Caputi AP. Beneficial effects of Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP), a superoxide dismutase mimetic, in zymosan-induced shock. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1241–1251. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan S, Chai H, Wang H, Yang H, Nan B, Yao Q, Chen C. Effects of lysophosphatidylcholine on monolayer cell permeability of human coronary artery endothelial cells. Surgery. 2005;138:464–473. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinores SA, Xiao WH, Shen J, Campochiaro PA. TNF-alpha is critical for ischemia-induced leukostasis, but not retinal neovascularization nor VEGF-induced leakage. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;182:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zittermann SI, Issekutz AC. Endothelial growth factors VEGF and bFGF differentially enhance monocyte and neutrophil recruitment to inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:247–257. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozaki H, Ishii K, Horiuchi H, Arai H, Kawamoto T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kita T. Cutting edge: combined treatment of TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma causes redistribution of junctional adhesion molecule in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:553–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wachtel M, Bolliger MF, Ishihara H, Frei K, Bluethmann H, Gloor SM. Down-regulation of occludin expression in astrocytes by tumour necrosis factor (TNF) is mediated via TNF type-1 receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J Neurochem. 2001;78:155–162. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin CW, Chen LJ, Lee PL, Lee CI, Lin JC, Chiu JJ. The inhibition of TNF-alpha-induced E-selectin expression in endothelial cells via the JNK/NF-kappaB pathways by highly N-acetylated chitooligosaccharides. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1355–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monaco C, Paleolog E. Nuclear factor kappaB: a potential therapeutic target in atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blum MS, Toninelli E, Anderson JM, Balda MS, Zhou J, O'Donnell L, Pardi R, Bender JR. Cytoskeletal rearrangement mediates human microvascular endothelial tight junction modulation by cytokines. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;273:H286–H294. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen LB, Stender S, Jauhiainen M, Nordestgaard BG. Preferential influx and decreased fractional loss of lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic compared with nonlesioned rabbit aorta. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:563–571. doi: 10.1172/JCI118824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patrick DM, Leone AK, Shellenberger JJ, Dudowicz KA, King JM. Proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma modulate epithelial barrier function in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells through mitogen activated protein kinase signaling. BMC Physiol. 2006;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aslan M, Ryan TM, Townes TM, Coward L, Kirk MC, Barnes S, Alexander CB, Rosenfeld SS, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide-dependent generation of reactive species in sickle cell disease. Actin tyrosine induces defective cytoskeletal polymerization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4194–4204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubanyi GM, Vanhoutte PM. Superoxide anions and hyperoxia inactivate endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:H822–H827. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.5.H822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldwin AL, Thurston G, al Naemi H. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis increases venular permeability and alters endothelial actin cytoskeleton. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1776–H1784. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cerimele F, Battle T, Lynch R, Frank DA, Murad E, Cohen C, Macaron N, Sixbey J, Smith K, Watnick RS, Eliopoulos A, Shehata B, Arbiser JL. Reactive oxygen signaling and MAPK activation distinguish Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-positive versus EBV-negative Burkitt's lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:175–179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408381102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kriegler M, Perez C, DeFay K, Albert I, Lu SD. A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF. Cell. 1988;53:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slowik MR, De Luca LG, Fiers W, Pober JS. Tumor necrosis factor activates human endothelial cells through the p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor but the p75 receptor contributes to activation at low tumor necrosis factor concentration. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1724–1730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, Goeddel DV. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1996;84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.