Abstract

Neonatal alloimmune neutropenia (NAN) is an uncommon disease of the newborn provoked by the maternal production of neutrophil-specific alloantibodies, whereby neutrophil IgG antibodies cross the placenta and induce the destruction of fetal neutrophils. Affected newborns are usually identified by the occurrence of bacterial infections. The most frequent antigens involved in NAN are the human neutrophil antigen-1a (HNA-1a), HNA-1b, and HNA-2a. We report a neonate who was delivered at 36 weeks and had a severe neutropenia but who responded well to recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rhG-CSF). Anti-HNA-1a antibody was identified by mixed passive hemagglutination assay in both the sera of the baby and the mother. The baby had HNA-1a and HNA-1b but the mother had only HNA-1b on granulocytes. This is the first Korean report of NAN in which the specificity of the causative antibody was identified.

Keywords: Infant, Newborn; Neutropenia; neutrophil-specific antigen NA1, human; Antibodies

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal alloimmune neutropenia (NAN) occurs when a mother becomes sensitized to a foreign antigen of paternal origin that is present on fetal granulocytes (1, 2). These fetal granulocyte antigens sensitize the mother and provoke antibody production. Moreover, immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody readily crosses the placenta and destroys fetal granulocytes by providing opsonic assistance to splenic macrophages (2). Neutropenia is typically self-limiting and last for several weeks, but can persist for as long as 6 months. During this period, neonates are at high risk of developing infections (2, 3). In NAN, symptomatic infants often present with delayed separation of the umbilical cord, skin infections, otitis media, or pneumonia within the first 2 weeks of life (2), and whereas most infections are mild, severe sepsis is known to occur. The mortality rate in NAN has been reported to be about 5% (2), and the severity of neutropenia is influenced by antibody titer and IgG subclass (1, 2). A wide variety of antigenic targets have been identified in NAN, but the antigens most commonly involved are human neutrophil antigen-1a (HNA-1a), HNA-1b, and HNA-2a (2, 4). Diagnosis of immune neutropenia is dependent on the demonstration of granulocyte-specific antibody in serum, which can be performed using (2, 5, 6) the granulocyte agglutination test (GAT), the granulocyte immunofluorescence test (GIFT), the monoclonal antibody immobilization of granulocyte antigens assay (MAIGA), and the mixed passive hemagglutination assay (MPHA). In the present study, MPHA was used to detect granulocyte-specific antibody.

Here we report a neonate with neonatal alloimmune neutropenia associated with anti-human neutrophil antigen-1a (anti-HNA-1a) antibody.

CASE REPORT

Clinical and laboratory history

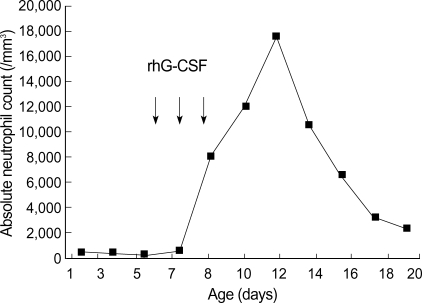

A female neonate was born from a healthy 30-yr-old, gravida 1, para 1 mother, whose first child was born without specific problems. The neonate, weighing 2,810 g, was born at gestation week-36 by spontaneous vaginal delivery. The baby appeared to be healthy and physical examinations revealed no abnormality. However, routine laboratory examinations on day 1 showed severe neutropenia: total white blood cell count (WBC) 7,200/µL, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) 430/µL. Other hematological and biochemical profiles were within normal limits. Blood and urine cultures were obtained and prophylactic gentamicin and ampicillin/sulbactam were administered for potential sepsis. On days 3 and 5, complete blood counts showed persistent severe neutropenia (ANC 320/µL and 200/µL, respectively). On day 6, recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rhG-CSF) therapy was started at 10 µg/kg/day. After 3 days of therapy, ANC increased to 8,100/µL (day 10) and rhG-CSF therapy was stopped. Blood and urine were sterile and thus to further evaluate neutropenia, blood samples were obtained from the patient and mother. Genotyping of granulocytes from patient and mother, and serum assays for granulocyte-specific antibody were performed. Polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP) was used for the granulocyte typing, and showed that the patient's granulocytes had both HNA-1a and HNA-1b but that the mother's had HNA-1b only. Patient's and maternal sera were found to contain granulocyte-specific antibodies against HNA-1a by mixed passive hemagglutination assay (MPHA). Antibodies were detected at 1:8 (patient) and 1:16 (mother) dilutions, respectively. Patient ANC peaked at 17,560/µL on day 12, and subsequently fell to more than 2,000/µL (Fig. 1). She was discharged home at 21 days of age.

Fig. 1.

Absolute neutrophil counts of patient during the day of life. Each arrow represents a single dose of rhG-CSF administered.

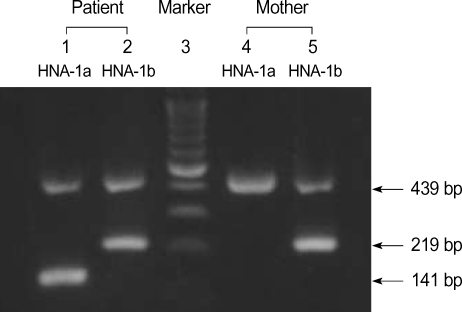

HNA-1a and HNA-1b genotyping

DNA was isolated from blood samples of the patient and her mother using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). To type HNA-1a and -1b, PCR-SSP was performed according to the protocols described by Bux et al. (7). NA1 (5'CAGTGGTTTCACAATGAA3') was used as a sense primer specific for HNA-1a (FCGR3B*1) and NA2 (5'CAATGGTACAGCGTGCTT3') for HNA-1b (FCGR3B*2). NA reverse (5'ATGGACTTCTAGCTGCAC3') was used as an antisense primer common to HNA-1a and HNA-1b. And, for internal control purposes, two primers (HGH I and HGH II) amplifying a 439 bp fragment of the human growth hormone gene (HGH) were used. Amplification was performed in a 20-µL reaction mixture containing the following: 0.2 µM of each primer; 200 µM (each) dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP; 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KCl; 1 unit of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Cetus, CT, U.S.A.); and 1 µL of DNA sample. Thirty cycles of amplification were preformed in a DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR 9600 system, Perkin-Elmer, Cetus, CT, U.S.A.). Each cycle consisted of the followings: predenaturation at 95℃ for 3 min, 30 amplification cycles of (denaturation at 95℃ for 1 min, primer annealing at 58℃ for 1 min, and extension at 72℃ for 1 min). The sizes of the amplified DNA fragments were 141 bp and 219 bp for the HNA-1a and HNA-1b genes, respectively (7). The mother had no HNA-1a and the patient had both HNA-1a and HNA-1b (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

NA-1a and -1b genotyping by PCR-SSP. Lane 3 shows a DNA ladder marker (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). The amplification products (439 bp) of the internal control (the HGH gene) is present in every lane. The genotype can be deduced from the presence of amplification products that are specific for HNA-1a (FCGR3B*1, 141 bp) and HNA-1b (FCGR3B*2, 219 bp). The patient had both HNA-1a and HNA-1b, but mother had HNA-1b (lane 5) only.

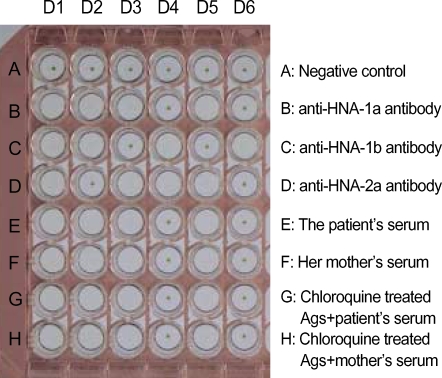

Granulocyte-specific antibody test using MPHA

To detect granulocyte-specific antibodies, sera from patient and mother were tested using MPHA. Extracted granulocyte antigens from 6 voluntary donors, whose granulocyte types were known, were coated in the well of U-bottomed microplates (Maxisorp Lockwellmodule, Nunc, Roskide, Denmark). The negative control serum used was derived from a healthy male donor with no history of transfusion, and positive control sera (anti-HNA-1a, anti-HNA-1b, and anti-HNA-2b) and indicator cells (sheep RBCs coated with rabbit F (ab')2 anti-human IgG) were provided by Prof. K. Takahashi (The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). The tests were performed according to the protocols described by Araki et al. (5). The sera of both patient and mother were reactive to the granulocyte antigens of donors 1, 2, 3, 5, which all contained HNA-1a (Fig. 3). To differentiate human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antibody and granulocyte-specific antibody, granulocyte antigens coated microwells were treated with 0.8 M chloroquine solution (5). After the chloroquine treatment, the sera were reactive in the same pattern (Fig. 3). Both patient and maternal serum were diluted, and anti-HNA-1a antibody reactivity persisted to dilutions of 1:8 and 1:16, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Granulocyte-specific antibody test by mixed passive hemagglutination assay (MPHA). The patient's and maternal sera (row E and F) reacted with granulocyte antigens of donors 1, 2, 3, and 5, which had HNA-1a in common (see row B). The reactive pattern did not change after treating granulocyte antigens with 0.8 M chloroquine (row G, H). Thus, both patient and mother had granulocyte-specific antibodies against HNA-1a. The granulocyte antigen types of the six donors were as follows (donor 1: HNA-1a, -1b, -2a; donor 2: HNA-1a, -1b; donor 3: HNA-1a, -2a; donor 4: HNA-1b, -2a; donor 5: HNA-1a, -2a; donor 6: HNA-1b).

D1-6, granulocyte donor 1-6; Ags, extracted granulocyte antigens.

DISCUSSION

Granulocyte antigens-NA1 (HNA-1a), NA2 (HNA-1b), and NB1 (HNA-2a) were first characterized by Lalezari and Radel in 1974 (8) and the human neutrophil antigens (HNA) system was proposed by Bux in 1999 (9). The HNA nomenclature is based on the glycoprotein locations of various antigens and the nomenclature of alleles according to the Guidelines of the International Workshop on Human Gene Mapping. The HNA system comprises seven antigens, which are assigned to five glycoproteins (9).

Antibodies against granulocyte antigens have been implicated in NAN, autoimmune neutropenia, and transfusion related acute lung injury (6, 10). However, no confirmed clinical report has been issued on these disorders in Korea, since the techniques required to identify granulocyte-specific antibodies are complicated. Here we used the MPHA technique to detect granulocyte-specific antibodies. Patient's serum samples were tested against a panel of granulocytes from six donors with known phenotypes to identify antibody specificities. However, the presence of HLA antibodies can make the detection of granulocyte-specific antibodies difficult (6). To remove HLA from extracted granulocyte antigens, we treated antigens with chloroquine. Subsequently, the panel of extracted granulocyte antigens did not react with anti-HLA antibody.

This is the first case of NAN due to anti-HNA-1a in Korea. The mother was a HNA-1b-homozygote and her baby was a HNA-1a/-1b heterozygote. The mother might have been sensitized with HNA-1a antigen during her first pregnancy, and this may have provoked the production of anti-HNA-1a antibody. HNA-1a and -1b are biallelic granulocyte antigens and are located on FcγRIIIb.

The frequencies of HNA-1a and -1b differ significantly in Caucasian and Asians (11, 12). HNA-1a and -1b gene frequencies have been reported to be 0.35 and 0.65 in Caucasians, 0.69 and 0.31 in Chinese, and 0.52 and 0.48 in Koreans, respectively (7, 11-13). Thus, HNA-1b homozygote pregnancies are more common in Caucasians than in Asians. In Caucasians, anti-HNA-1a antibodies are the most commonly detected in NAN (14, 15). However, no data is available on NAN antibody frequencies in Asians. However, in view of the reported HNA-1a and -1b gene frequencies, fetomaternal granulocyte mismatches due to HNA-1b may be more common in Asians than in Caucasians, and anti-HNA-1b antibodies may be more common in Asians. Zupanska et al. reported fetomaternal granulocyte antigen mismatches (HNA-1a and -1b only) in 19.6% of mothers, and granulocyte-specific antibodies in 4.5% of fetomaternal incompatible mothers (alloimmunization in 0.9% of mothers). The authors suggested that NAN related to the two antigens (HNA-1a and -1b) occurs in less than 0.1% and severe NAN in 0.06% (14). However, similar information is unavailable on other antigens implicated in NAN, and a much higher frequency of NAN would be expected based on considerations of all possible fetomaternal granulocyte antigen mismatches. Estimates of the frequency of NAN can vary widely and range from 0.2 to 20% (1, 2), but such estimates are not easily compared because of differences in study designs, period, and the different laboratory methods used. A wide variety of antigens including the HNA system and HLA have been identified in NAN (1, 2, 16). However, the antigens involved are unidentified in almost half of all cases (2, 16), and nearly a half of all cases are mediated by antibodies that bind to HNA-1a, -1b, or -2a (2, 15). Our unpublished data suggest that the incidence of alloimmunization against granulocyte antigens is 3.5% (6/170) in mothers (HNA-1a and -1b, 2.4% [4/170]), and that the incidence of NAN is more than 0.07% (1/1,500) among Korean newborns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Prof. Y. Shibata and Prof. K. Takahashi for their kind advice and support.

References

- 1.Maheshwari A, Christensen RD, Calhoun DA. Resistance to recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in neonatal alloimmune neutropenia associated with anti-human neutrophil antigen-2a (NB1) antibodies. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E64. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maheshwari A, Christensen RD, Calhoun DA. Immune-mediated neutropenia in the neonate. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2002;91:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb02912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore MM, Stroncek DF, Korones DN. Treatment of alloimmune neonatal neutropenia with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Pediatr. 1994;125:948–951. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bux J, Chapman J. Report on the second international granulocyte serology workshop. Transfusion. 1997;37:977–983. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37997454028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araki N, Nose Y, Kohsaki M, Mito H, Ito K. Anti-granulocyte antibody screening with extracted granulocyte antigens by a micro-mixed passive hemagglutination method. Vox Sang. 1999;77:44–51. doi: 10.1159/000031073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stroncek D. Granulocyte antigens and antibody detection. Vox Sang. 2004;87:91–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6892.2004.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bux J, Stein EL, Santoso S, Mueller-Eckhardt C. NA gene frequencies in the German population, determined by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers. Transfusion. 1995;35:54–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35195090663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalezari P, Radel E. Neutrophil-specific antigens: immunology and clinical significance. Semin Hematol. 1974;11:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bux J. Nomenclature of granulocyte alloantigens. Transfusion. 1999;39:662–663. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39060662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroncek D. Neutrophil alloantigens. Transfus Med Rev. 2002;16:67–75. doi: 10.1053/tmrv.2002.29406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas GF, Metcalfe P. Platelet and granulocyte glycoprotein polymorphisms. Transfus Med. 2000;10:157–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2000.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han KS, Um TH. Frequency of neutrophil-specific antigens among Koreans using the granulocyte indirect immunofluorescence test (GIFT) Immunohematology. 1997;13:15–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo DH, Park SS, Han KS. Genotype analysis of granulocyte-specific antigens in Koreans. Korean J Clin Pathol. 1997;17:1144–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zupanska B, Uhrynowska M, Guz K, Maslanka K, Brojer E, Czestynska M, Radomska I. The risk of antibody formation against HNA1a and HNA1b granulocyte antigens during pregnancy and its relation to neonatal neutropenia. Transfus Med. 2001;11:377–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2001.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bux J, Jung KD, Kauth T, Mueller-Eckhardt C. Serological and clinical aspects of granulocyte antibodies leading to alloimmune neonatal neutropenia. Transfus Med. 1992;2:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.1992.tb00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagimoto R, Koike K, Sakashita K, Ishida T, Nakazawa Y, Kurokawa Y, Kamijo T, Saito S, Hiraoka A, Kobayashi M, Komiyama A. A possible role for maternal HLA antibody in a case of alloimmune neonatal neutropenia. Transfusion. 2001;41:615–620. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41050615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]