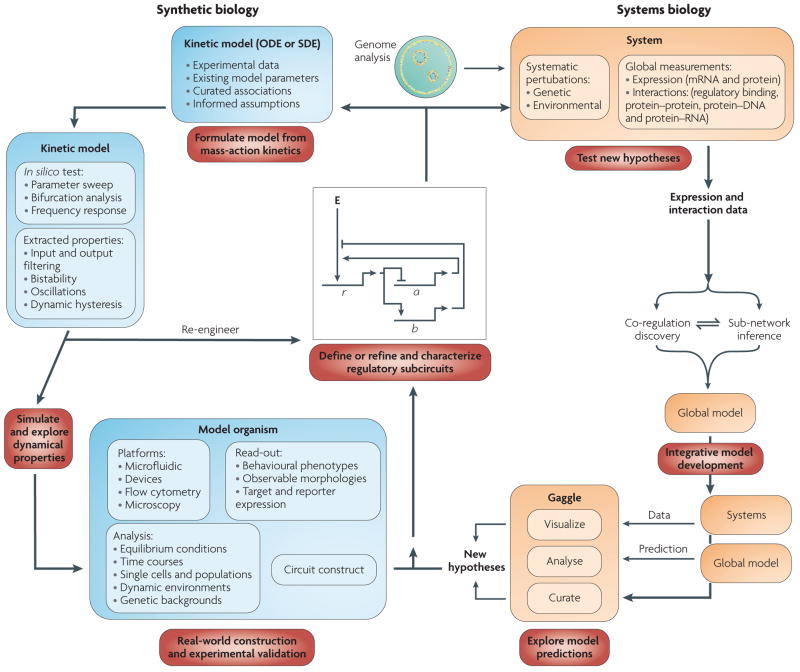

Figure 2. convergence of systems and synthetic biology.

The systems biology cycle begins with a specific hypothesis that is tested by systematic perturbations through targeted environmental and genetic changes. Molecular changes are measured globally at multiple levels (for example, transcription, translation and physical interactions) using high-throughput technologies. This produces large and diverse data sets that drive the development of algorithms to process raw signal and integrate all available information to infer predictive models of how the inputs (environmental and genetic perturbations) were converted to outputs (for example, phenotypes, transcriptional changes and interactions)102. Owing to the complexity of these models, their exploration requires a framework that enables the integration and interoperation of diverse databases and applications for visualizing and analysing the data used to construct the models103. The exploration of systems models enables a biologist to design experiments to test model predictions using classical genetics, biochemistry and molecular biology approaches. This helps define subcircuits and feeds the next iterations of the systems and synthetic biology cycles. In the synthetic biology cycle, the hypothesis begins as a specific network topology, regulatory subcircuit or set of molecular interactions. The system is mathematically formulated as systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), stochastic differential equations (SDEs) or a stochastic reaction network to produce a quantitative and kinetic representative model that is fit for computational simulation and testing. Key parameters of the system (synthesis and degradation rates, binding cooperativities and association or dissociation constants) are derived based on estimates from other models of well known systems. The system is analysed by focusing on exploring the parameter space and testing the kinetic properties of the system (for example, through frequency response analysis) to locate the regimes of desired dynamic behaviour and define their limits. Simulations elucidate revisions in the topology of the system to produce the desired output or enhance unexpected, but desirable, dynamic characteristics. Once these characteristics are well defined computationally, they are verified experimentally through system construction and implementation. Experimental exploration of the parameter space is performed using flow cytometry and microfluidics83-based assays, which provide high-throughput measurements at population and single cell scales simultaneously. Finally, the experimental implementation incorporates revisions, leading to another iteration of computational modelling to validate the dynamics of the system. New challenges to construct hybrid models that link detailed ODE or SDE models of subcircuits to the statistically learned systems models will emerge. We suggest that such a tandem ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approach will be essential to precisely manipulate a biological circuit and accurately predict its system-level outcomes. E represents an effector (either global regulatory influences or environmental factors), r represents a regulator gene, a represents gene A and b represents gene B.