Abstract

Compulsive hoarding (the acquisition of and failure to discard large numbers of possessions) is associated with substantial health risk, impairment, and economic burden. However, little research has examined separate components of this definition, particularly excessive acquisition. The present study examined acquisition in hoarding. Participants, 878 self-identified with hoarding and 665 family informants (not matched to hoarding participants), completed an internet survey. Among hoarding participants who met criteria for clinically significant hoarding, 61% met criteria for a diagnosis of compulsive buying and approximately 85% reported excessive acquisition. Family informants indicated that nearly 95% exhibited excessive acquisition. Those who acquired excessively had more severe hoarding; their hoarding had an earlier onset and resulted in more psychiatric work impairment days; and they experienced more symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and anxiety. Two forms of excessive acquisition (buying and free things) each contributed independent variance in the prediction of hoarding severity and related symptoms.

Keywords: obsessive compulsive disorder, hoarding, compulsive buying, excessive acquisition

Compulsive hoarding has come to light as an important yet little-studied psychopathology (Steketee & Frost, 2003). It represents a serious and sometimes life-threatening behavior (Frost, Steketee, & Williams, 2000), particularly for the elderly (Steketee, Frost, & Kim, 2001), and it poses significant economic and family burden (Tolin, Frost, Steketee, & Fitch, 2008; Tolin, Frost, Steketee, Gray, & Fitch, 2008). Historically resistant to treatment (see Steketee & Frost, 2003), development of a specific cognitive behavior therapy for hoarding has shown some promise (Steketee & Frost, 2007; Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2007).

Further improvements in treatment efficacy would likely be facilitated by a more precise definition of the syndrome. Frost and Hartl (1996) defined hoarding as consisting of the following key elements: (1) The acquisition of a large number of possessions, (2) subsequent failure to discard possessions, and (3) resulting clutter that precludes the use of living spaces in the manner for which those spaces were designed. Clutter is the most visible manifestation of compulsive hoarding, and the distinction in living conditions between hoarding and non-hoarding samples is clear (Frost, Steketee, Tolin, & Renaud, 2008). Difficulty discarding is evident by exaggerated beliefs about responsibility toward, attachment, to, and need to control possessions (Frost, Hartl, Christian, & Williams, 1995; Steketee, Frost, & Kyrios, 2003), as well as hoarding patients’ higher subjective ratings of anxiety during decisions about whether to keep or discard possessions, longer time to discard possessions, and greater refusal to discard possessions compared to healthy control participants (Tolin, Kiehl, Worhunsky, Book, & Maltby, 2007).

By comparison, Frost and Hartl’s (1996) first criterion, the acquisition of a large number of possessions, has received less empirical study and its role in compulsive hoarding is less clear. People who hoard must acquire things in order to clutter their homes, but is their acquisition always excessive or different from normal? In 14 case studies of hoarding involving 37 different patients, specific mention of aberrant collecting behavior was evident in 59% (22) of the cases (Cole, 1990; Cermele, Melendez-Pallitto & Pandina, 2001; Damecour & Charron, 1998; Drummond, Turner, & Reid, 1996; Fitzgerald, 1997; Frost, Steketee, Youngren & Mallya, 1998; Greenberg, 1997; Greenberg, Witzum, & Levy, 1990; Greve, Curtis, & Bianchini, 2004; Hartl & Frost, 1999; Rosenthal, 1999; Shafran & Tallis, 1996; Thomas, 1997; Vostanis & Dean, 1992). Compulsive buying, collecting free things, and occasionally stealing constituted the types of acquisition. Several of the reports that did not mention acquisition contained only short descriptions of each case. In these reports it was unclear whether abnormal acquisition was absent or overlooked.

One common method of acquisition is buying. Compulsive buying afflicts roughly six percent of the U.S. population (Koran, Faber, Aboujaoude, Large, & Serpe, 2007) and can have serious personal, social, and financial consequences (McElroy, Keck, Pope, Smith, & Stakowski, 1994). Compulsive buying has been found to be associated with a number of disorders including depression (Christenson et al., 1994), obsessive compulsive disorder (Frost, Steketee, & Williams, 2002; Lejoyeux, Bailly, Moula, Loi, & Ades, 2005), anxiety disorders (Christenson et al., 1994), eating disorders (Christenson et al., 1994), and pathological gambling (Frost, Meagher, & Riskind, 2001). Several studies have suggested an association between compulsive buying and hoarding severity. Self-identified hoarders report significantly more buying of extra items in anticipation of potential need (Frost & Gross, 1993), and report higher levels of compulsive buying than do control participants (Frost et al., 1998). Severity of hoarding symptoms (e.g., clutter, difficulty discarding) is also significantly correlated with severity of compulsive buying (Coles et al., 2003; Frost et al., 1998; Frost, Steketee, & Grisham, 2004; Frost et al., 2002; Mueller et al., 2007). Individuals identified with compulsive buying report significantly higher levels of compulsive hoarding than do community controls (Frost et al., 2002) and endorse beliefs about possessions that appear similar to those seen in hoarding patients (Kyrios, Frost, & Steketee, 2004). Approximately half of compulsive buyers display elevated levels of hoarding (Mueller et al., 2007).

Other acquired items may be obtained for free (e.g., free brochures, giveaways, and discarded items). In the hoarding case studies described above, the majority (20 out of 37 cases) described the tendency to excessively acquire free things. In fact, among the case studies, this behavior was mentioned more frequently than was compulsive buying (only 4 out of 37 cases). Other research has found that hoarders attending a self-help group reported higher levels of acquisition of free things than people without hoarding problems (Frost et al., 1998), and the degree of acquisition of free things correlated significantly with other symptoms of hoarding as well as with compulsive buying (Frost et al., 2002).

These studies suggest that compulsive hoarding is associated with both compulsive buying and the excessive acquisition of free things, though the relatively small sample sizes in these studies make the conclusions tentative, and it remains to be seen how often hoarding is accompanied by excessive acquisition. In our own experience, we have seen cases in which the acquisition was more passive in nature. For example, some patients report that they do not actively go out and acquire objects; rather, items such as newspapers, “junk” mail, and empty food containers accumulate in the home during routine use because of the individual’s difficulty discarding. In addition, Frost et al. (2004) found lower correlations between the acquisition subscale of the Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R) and hoarding-related beliefs than were observed for the other SI-R subscales, suggesting that acquisition may not be a core feature of hoarding.

The first purpose of the present investigation was to determine the frequency of excessive acquisition in a large sample of compulsive hoarding cases. A second aim was to determine the frequency with which the acquisition occurred in the form of compulsive buying, excessive acquisition of free things, or both. If there is a subset of people who hoard but do not acquire excessively (i.e., acquisition is passive, rather than active), it would be important to know whether they differ from people who both hoard and acquire excessively in the severity of their hoarding symptoms, age of onset, and psychiatric comorbidity. Because hoarding has been associated with lack of insight (Tolin, Fitch, Frost, & Steketee, 2007), self-reports of excessive acquisition may be subject to distortion. For instance, people with hoarding problems may acquire excessively, but not recognize it. Accordingly, we also surveyed a large cohort of family members of hoarders about their hoarding family members’ behaviors, including acquiring.

Finally, little is known about the excessive acquisition of free things. Although strongly correlated with compulsive buying (Frost et al., 2002), excessive acquisition of free things appears associated with other constructs. For instance, while compulsive buying correlated with measures of materialism, the excessive acquisition of free things did not (Frost, Kyrios, McCarthy, & Mathews, 2007). A final purpose of this study was to examine the relationship of the excessive acquisition of free things (versus compulsive buying) with symptoms of psychopathology (e.g., depression, obsessive compulsive disorder), as well as hoarding-related measures.

Method

Participants

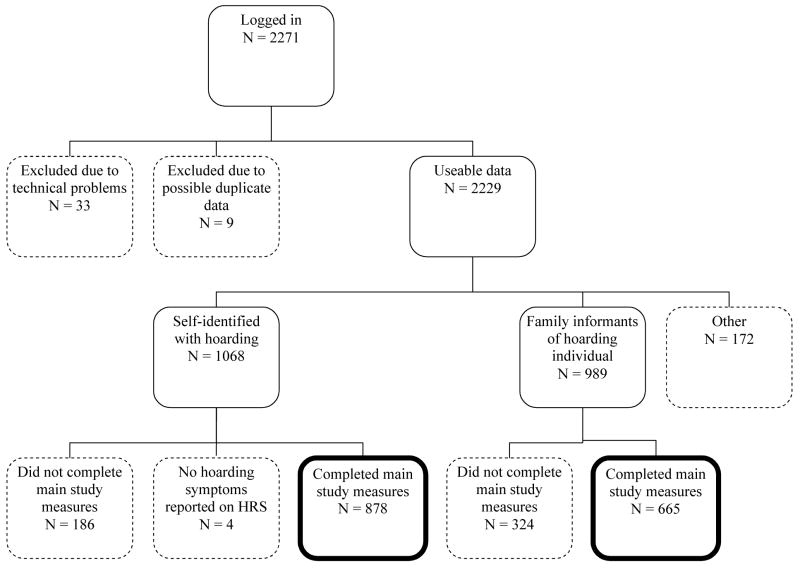

The present sample was recruited from a database of over 8,000 individuals who have contacted the researchers over the past 3 years for information about compulsive hoarding after several national media appearances. Potential participants were sent an e-mail invitation to participate in the study, and were also allowed to forward the invitation to others with similar concerns. Data collection occurred from November 14, 2006 to January 15, 2007. Consistent with current recommendations (Kraut, Olson, & Banaji, 2004), prior to analysis the data were checked for apparent duplicates (i.e., a participant completing the survey more than once). A flowchart of participation is shown in Figure 1. Of 2271 respondents, 878 people who self-identified with hoarding problems (hoarding participants) completed the main study measures (93% female). In addition, 665 family informants reported on acquisition and hoarding behavior of a family member who hoarded (hoarding family members). Findings from this sample are reported elsewhere (Tolin, Frost, Steketee, & Fitch, 2008). Only data from the family members’ Hoarding Rating Scale-Self Report were used in the present study. We note that the hoarding family members were not assessed directly in the present study. Among the full sample of hoarding participants, 37.8% met or exceeded the cutoff for clinically significant OCD (4) based on the OCI-SV obsessing subscale (Foa et al., 2002)

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Participation.

Note: exclusions are indicated by dashed lines. Final samples are indicated by bold lines.

Materials

Diagnosis and severity of compulsive hoarding was determined using a self-report version of the Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview (HRS-I; Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2007b), termed the Hoarding Rating Scale-Self-Report (HRS-SR). Like the interview, the HRS-SR consists of 5 Likert-type ratings from 0 (none) to 8 (extreme) of clutter, difficulty discarding, excessive acquisition, distress, and impairment. The HRS-I has shown high internal consistency and inter-rater reliability, correlated strongly with other measures of hoarding, and reliably discriminated hoarding from non-hoarding participants (Tolin et al., 2008).

Severity of hoarding on the HRS-SR was determined by calculating the sum of all 5 items. For selected analyses, an HRS-SR subtotal was calculated (HRS-SR Sub) by subtracting the acquisition item. Participants were considered to meet criteria for clinically significant hoarding if they described moderate (4) or greater clutter and difficulty discarding, as well as either moderate (4) or greater distress or impairment caused by hoarding on the HRS-SR. The cutoff of 4 is arbitrary, although this is consistent with diagnostic strategies used for other disorders on similar rating scales (Brown, DiNardo, & Barlow, 1994). Hoarding participants completed the HRS-SR for their own symptoms and family informants completed the HRS-SR for the identified hoarding family member. We tested the reliability of HRS-SR on a separate sample of 31 participants in another study for whom an HRS-I was also available. The HRS-I and HRS-SR correlated strongly (r =.92, p <.001), with individual item correlations ranging from .74–.91. Hoarding diagnostic status (see above) showed 73% agreement between self and interviewer report.

The Compulsive Acquisition Scale (CAS ; Frost et al., 2002) is an 18-item Likert-type scale (from 1 = not at all or rarely to 7 = very much or very often) that measures the extent to which individuals acquire and feel compelled to acquire possessions. Two sub-scales were used: CAS-Buy and CAS-Free. The 12-item CAS-Buy subscale is a broad measure of compulsive buying behavior and its consequences. Two items refer to interference of buying in financial, social, or work functioning, and the remaining items focus on reasons for acquiring possessions, including four questions of the frequency of inappropriate buying, two on feeling compelled to buy, and four on emotional reactions to buying. The CAS-Free, a 6-item subscale, measures the excessive acquisition of free objects. Both the CAS-Buy and CAS-Free have been found to be reliable (Frost et al., 2002; Kyrios et al., 2004). Both have been found to be correlated with buying-related cognitions, OCD symptoms, perfectionism, and indecisiveness. In addition, CAS-buy discriminates compulsive buyers from controls (Frost et al., 2002; Kyrios et al., 2004). Reliability in the present sample was satisfactory (αs = 0.90 and 0.73, respectively). In the present sample the two subscales were significantly correlated (r =.50).

Cutoff scores for clinically significant compulsive buying on the CAS were established from an earlier study (Frost et al., 2002) by constructing receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) distinguishing individuals with clinical significant compulsive buying (N = 75) from non compulsive buyers (N=114). The area under the curve was significant (AUC =.922, p <.001), and a cutoff score of 47.8 maximized sensitivity (.85) and specificity (.84).

The Frost Indecisiveness Scale (FIS; Frost & Shows, 1993) is a 15-item scale measuring difficulties with decision-making, and comprises two subscales: (1) Fears about Decision-Making consisting of nine items, and (2) Positive Attitudes towards Decision-Making consisting of six items. The FIS demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in undergraduate samples (Frost & Shows, 1993), with Fears about Decision-Making previously shown to be associated with both compulsive hoarding and buying (Frost et al., 2002; Kyrios, et al., 2004). Both subscales demonstrated satisfactory reliability (αs = 0.86 and 0.81, respectively) in the present study.

We also administered the Clutter Image Rating (CIR; Frost et al., 2008), a series of 9 photographs each of a kitchen, living room, and bedroom with varying levels of clutter. Family informants select the photograph that most closely resembles each of the three rooms in the hoarding family member’s home. Scores for each room are scaled from 1 to 9, and a mean composite score is calculated across the three rooms (range 1–9). In the original study, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability for the CIR were high, as were correlations with validated hoarding measures (Frost et al., 2008). Internal consistency was high in the present sample (α =.85).

Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002). The OCI-R is an 18-item self-report measure of OCD symptoms containing subscales covering Hoarding, Checking, Neutralizing, Obsessing, Ordering, and Washing. In a large clinical sample, the subscales showed good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity with other measures of OCD symptoms (Foa et al., 2002). In the present sample, acceptable internal consistency was obtained for Checking (α =.82), Hoarding (α =.87), Neutralizing (α =.88), Obsessing (α =.93), Ordering (α =.86), and Washing (α =.89).

The short form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) is a 21-item version of the original DASS (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) and contains three subscales, depression, anxiety, and stress. Psychometric analyses indicate that the short form is a reliable and valid instrument (Henry & Crawford, 2005).

An Economic Impact Questionnaire (EIQ) was developed by the present authors to examine the economic and social burden of hoarding (see Tolin, Frost, Steketee, Gray, & Fitch, 2008). Questions on the EIQ were taken verbatim from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) interview (Kessler, McGonagle, & Zhao, 1994). Specifically, hoarding participants were asked about psychiatric work loss days (number of days in the past month that the respondent was unable to work or carry out usual activities due to mental health issues) and psychiatric work cutback days (number of days in the past month that the respondent was less effective at work or in activities due to mental health issues) (Kessler & Frank, 1997). Consistent with previous research (Kessler, Mickelson, & Barber, 2001), total psychiatric work impairment was calculated as the number of psychiatric work loss days plus 50% of the number of psychiatric work cutback days. Although studies have differed in how psychiatric work impairment was calculated, this method is now preferred and is being used in analyses from the NCS replication study (R.C. Kessler, personal communication, February 10, 2007). In addition, participant income was collected using a NCS-adapted question.

Age of onset of hoarding problems was assessed by asking participants to report the extent to which hoarding was no problem, a mild problem, a moderate problem, or a severe problem at each five year interval beginning from birth (e.g., 1 = age 0–5; 2 = age 6–10; 3 = age 11–15, etc.). The age of onset scores used for this study reflected the intervals at which hoarding severity first became mild (noticeable) and moderate (clinically significant) since these represented indices of onset. The midpoints of each interval were used as data points in the statistical analyses.

Procedure

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Hartford Hospital, Smith College, and Boston University. Human subjects’ protection was consistent with current recommendations for web-based studies (Kraut et al., 2004). Prior to data collection, participants read an informed consent page and indicated consent by clicking an icon on the page. No protected health information was collected and it was not possible to link study data to an individual or computer. As incentive, participants were given an email address to enroll in a raffle to receive one of 10 copies of a self-help book on compulsive hoarding. Participants responded to the survey by computer. They were allowed to skip any questions they wished, or to complete only portions of the survey. Data were stored on a password-protected server. A summary of aggregate research results was emailed to all individuals in the original database.

Results

Frequency of Excessive Acquisition in Hoarding

Six-hundred and fifty-three participants met criteria for clinically significant hoarding based on their responses to the HRS-SR, though all 878 participants reported hoarding behavior that had a negative impact on their lives. Examination of the HRS-SR acquisition item revealed that 85.5% of clinically significant hoarding participants (558/653) reported at least moderate acquisition problems (a score of 4 or higher). Among informants with a clinically significant hoarding family member, 94.7% (540/570). reported excessive acquiring (4 or higher on the HRS) by their hoarding family member.

Among the 653 clinically significant hoarding participants, 61.1% met diagnostic criteria for compulsive buying based on their Compulsive Acquisition Scale buying scores (CAS-buy > 47.8). Many more reported excessive levels of buying. Seventy-four percent (482/653) scored more than one standard deviation above the mean of community controls (> 41.1) from Frost et al. (2002).

Regarding scores on the CAS-free subscale, 57.4% (375/653) scored higher than one standard deviation above that mean of community controls (>23.1) from Frost et al. (2002).. A total of 80.9% (528 of 653) scored higher than one standard deviation above the mean for community controls on one or both the CAS-buy and CAS-free subscales. Only 7% (46) exceeded this criterion for CAS-free but not CAS-buy, while 23.4% (153) exceeded the criterion for CAS-buy but not CAS-free.

Comparison of Hoarding Participants with and without Excessive Acquisition

Although excessive acquisition occurs in a large portion of people with hoarding problems, it appears that up to 20% of compulsive hoarding cases do not report excessive levels of acquisition. To determine whether hoarders with and without significant acquisition problems differed on key characteristics, one way (three group) analyses of variance were conducted comparing participants meeting our criteria for significant hoarding who experienced none (n = 125), one (n = 199), or two (n = 329) forms of excessive acquisition. Participants who scored greater than one standard deviation above the mean for the general population on CAS-Buy (Criterion = 41.1) and CAS-Free (Criterion = 23.1) were considered excessive based on data provided by Frost et al. (2002). Since only 7% (n=46) of participants engaged in excessive acquisition of free things without also buying excessively, and since a comparison of participants who only bought versus those who only acquired free items revealed no differences on any of the dependent variables, these groups were combined to form the single method of acquisition group.

The analyses comparing groups revealed a significant effect for age, F(2,619) = 4.35, p <.05. Tukey b multiple comparisons indicated that participants who experienced no excessive acquisition (M = 51.9, SD = 10.4) were significantly older than participants who experienced one (M = 48.7, SD = 9.9) or both (M = 48.6, SD = 10.9) forms of acquisition; the latter two groups did not differ from one another. There were no significant differences for income and chi square analyses failed to reveal any significant differences for gender.

We then examined differences among groups on dependent measures of interest. Because controlling for age via covariance analyses did not affect the significance of the findings, we report only analyses of variance here.

Regarding hoarding-related symptoms, ANOVAs comparing acquisition groups revealed significant differences among groups on the HRS-SR subtotal, CIR ratings, and impairment days (see Table 1). For HRS-SR subtotal and CIR ratings, post hoc analyses indicated that participants who had no excessive acquisition had lower scores than did both of the excessive acquisition groups which did not differ from each other. For impairment days, participants who had both forms of excessive acquisition reported significantly more impairment days than those who had no or only one form of excessive acquisition. The magnitude of the overall F-test effects is indicated by partial eta-squared (η2p) where .01 indicates a small effect, .06 a medium effect and .14 a large effect. Effect sizes for these comparisons were small to moderate.

Table 1.

Means, (s.d’s), and Analyses of Variance Comparing Acquisition Groups on Hoarding Severity and Related Variables

| Dependent Variable | No Acquisition | One Form of Acquisition | Both Forms of Acquisition | F | p | partial ETA2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRS-SR sub | 23.8 (4.0) a | 25.9 (3.9) b | 26.7 (3.5) b | 26.5 | .001 | .075 |

| CIR | 3.3(1.3) a | 3.7(1.5) b | 4.0(1.4) b | 10.1 | .001 | .031 |

| Impairment days | 4.5(7.4) a | 6.1(7.8) a | 8.5(8.8) b | 10.5 | .001 | .036 |

| Onset Age of Mild Hoarding | 17.6(11.2) a | 13.8(9.7) b | 13.0(9.2) b | 6.7 | .001 | .022 |

| Onset Age of Moderate Hoarding | 30.4(11.7) a | 25.4(12.9) b | 24.2(12.5) b | 6.1 | .002 | .021 |

| DASS – Dep | 15.0(10.9) a | 17.9(10.9) a | 21.2(11.7) b | 13.9 | .001 | .045 |

| DASS – Anx | 8.1(7.7) a | 9.1(8.2) a | 13.0(10.0) b | 17.3 | .001 | .055 |

| DASS – Str | 13.5(9.1) a | 16.7(9.8) b | 21.4(10.8) c | 28.7 | .001 | .088 |

| OCI total | 10.9(9.0) a | 13.5(9.4) b | 17.4(12.0) c | 16.8 | .001 | .055 |

| Fear of Decisions | 27.0(7.3) a | 30.7(7.3) b | 34.5(6.2) c | 60.2 | .001 | .159 |

| Positive Decision Making | 17.3(4.6) a | 16.6(4.9) a | 14.6(4.4) b | 21.8 | .001 | .064 |

Note: HRS-SR Sub = Hoarding Rating Scale without acquisition item; CIR = Clutter Image Rating; DASS - Dep = Depression; DASS – Anx = Anxiety; DASS – Str = Stress

Means with different superscripts differ significantly at p <.05 using Tukey’s B.

The onset of mild as well as moderate hoarding symptoms was earlier for participants with one or both forms of excessive acquisition than for those without excessive acquiring. The two acquisition groups did not differ from each other. Mild symptoms for the excessive acquisition groups began around age 13, while for the non-acquisition group they began around age 18. Moderate hoarding symptoms began around ages 35 for the excessive acquisition groups and 44 for the non-acquisition group.

There were significant differences across the groups on all three subscales of the DASS (see Table 1). For both the Depression and Anxiety subscales, participants with both forms of excessive acquisition had higher scores than did the participants with only one form or no excessive acquisition. These two groups did not differ from each other. For the Stress subscale, all three groups differed significantly; participants with both forms of excessive acquisition were highest followed by the group with one form of excessive acquisition and then the no acquisition group. A similar pattern was observed for the OCI total score and fear of decision making. Participants with both forms of excessive acquisition scored significantly lower on positive decision making than the other two groups which did not differ. Effect sizes for these comparisons were moderate, with the exception of fear of decisions which showed a large effect.

Correlation of Compulsive Buying and Excessive Acquisition of Free Things with hoarding, decision-making, OCD symptoms, and DASS

Correlations were used to determine the association between acquisition and other indices of hoarding, indecisiveness, OCD symptoms, distress, and depression (see Table 2) using all 878 participants to provide the broadest range of severity of acquiring behavior. Both CAS-buy and CAS-free were significantly correlated with all study variables (p’s <.001). The magnitude of the correlations were similar for each form of acquisition, though compulsive buying appeared more closely associated with DASS scores than excessive acquisition of free things.

Table 2.

Correlations of CAS-Buy and CAS-Free with study variables

| CAS-Buy | CAS-Free | |

|---|---|---|

| HRS-SR Subtotal | .46 | .40 |

| CIR | .32 | .25 |

| Impairment Days | .30 | .21 |

| Fear of Decisions | .38 | .43 |

| Positive Decision Making | −.15 | −.25 |

| OCI-neutralization | .23 | .22 |

| OCI-obsessions | .31 | .24 |

| OCI-order | .24 | .26 |

| OCI-washing | .19 | .21 |

| OCI-checking | .24 | .29 |

| OCI-hoarding | .46 | .53 |

| DASS-depression | .32 | .21 |

| DASS-anxiety | .34 | .25 |

| DASS-stress | .38 | .31 |

All r’s significant at p <.001.

Relative Contribution of Compulsive Buying and Excessive Acquisition of Free Things

In order to determine whether buying and free acquiring contributed independently to other indices of hoarding and related phenomena, we conducted a series of multiple regressions including all 878 participants. With regard to demographic variables, correlational analyses indicated that buying, but not free item acquisition, was significantly associated with age (r = −.14, p <.001; buyers were younger) and conversely that acquiring free things, but not buying, was negatively correlated with income (r = −.13, p <.001; those who acquired free items were poorer). Also, women in the current sample had significantly higher scores on the buying measure, t(874) = 2.5, p <.05. For these reasons, age, income, and gender were entered into the equation at step one. In addition, to determine whether excessive acquisition was related to hoarding independent of OCD symptoms and mood, the DASS depression subscale and the OCI subtotal (without hoarding) were also entered at step one. CAS-buy and CAS-free were entered at step 2. Although the CAS subscales were significantly correlated (as were the DASS subscales), multicolinearity indices were within normal limits (VIF’s ranged from 1.44 to 1.57).

Compulsive buying and the excessive acquisition of free things both made significant and independent contributions to the prediction of HRS-SR subtotal as well as each individual item on the scale (see Table 3). Only compulsive buying predicted CIR scores and psychiatric work impairment days due to hoarding, while only the excessive acquisition of free things predicted the onset of both mild and moderate hoarding symptoms. Both forms of acquisition predicted significant and independent variance in fears of decision making, but only the excessive acquisition of free things negatively predicted positive decision making (those who acquired free items were less confident in their decision-making). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Standardized Regression Coefficients Predicting Hoarding Severity while controlling for age, gender, income, OCI and DASS -D.

| Dependent and Predictor Variables | Standardized Coefficient Beta | t | p | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRS-SR Sub | 40.1 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .295 | 7.4 | .001 | ||

| CAS-Free | .189 | 4.9 | .001 | ||

| HRS –SR #1: Clutter | 19.7 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .243 | 5.6 | .001 | ||

| CAS-Free | .119 | 2.8 | .005 | ||

| HRS –SR #2: Discarding | 18.5 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .129 | 3.0 | .003 | ||

| CAS-Free | .266 | 6.3 | .001 | ||

| HRS –SR 3: Acquisition | 74.5 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .540 | 15.1 | .001 | ||

| CAS-Free | .218 | 6.3 | .001 | ||

| HRS –SR #4: Distress | 36.0 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .295 | 7.3 | .001 | ||

| CAS-Free | .134 | 3.4 | .001 | ||

| HRS-SR #5: Interference | 29.0 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .283 | 6.8 | .001 | ||

| CAS-Free | .101 | 2.5 | .012 | ||

| Clutter Image Rating | 17.3 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .278 | 6.3 | .001 | ||

| CAS-Free | .047 | 1.1 | .272 | ||

| Impairment Days | 37.0 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .138 | 3.3 | .001 | ||

| CAS-Free | .030 | 0.73 | .465 | ||

| Onset Age for Mild Hoarding | 17.0 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | −.062 | −1.4 | .158 | ||

| CAS-Free | −.114 | −2.7 | .007 | ||

| Onset Age for Moderate Hoarding | 41.5 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .024 | 0.53 | .596 | ||

| CAS-Free | −.114 | −2.6 | .02 | ||

| Fear of Decisions | 48.7 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .114 | 2.9 | .004 | ||

| CAS-Free | .307 | 8.1 | .001 | ||

| Positive Decision Making | 13.8 | .001 | |||

| CAS-Buy | .033 | 0.74 | .459 | ||

| CAS-Free | −.224 | −5.2 | .001 |

HRS-SR Subtotal = Hoarding Rating Scale-Self Report without acquisition item; CAS = Compulsive Acquisition Scale.

Discussion

The findings of the present study indicate that excessive acquisition occurs with a very high frequency among people with significant hoarding defined as at least moderate difficulty discarding and clutter and moderate distress or interference. Only a small subset of these participants did not acquire excessively. Furthermore, both forms of excessive acquisition were related to hoarding severity and indecisiveness independent of OCD and distress. These findings have implications for the definition of hoarding and the development of diagnostic criteria if this problem is to be considered as a disorder separate from OCD as some have recommended (McKay, Abramowitz, & Taylor, 2008; Saxena, 2007).

The high frequency and levels of excessive acquisition in a large compulsive hoarding sample and the fact that acquisition indices predicted hoarding independent of OCD and measures of distress/depression suggest that excessive acquisition can be considered a central component of the disorder. However, a small group of participants (ranging from 5 to 19% in these samples) reported significant hoarding but little acquisition. Several alternatives might explain this. One possibility is that some people with hoarding acquire passively and not excessively, so clutter accumulates gradually over time because they are unable to discard items. Consistent with this explanation is the somewhat later onset age for those with moderate hoarding (mid 40’s) who reported no acquiring compared to those with one or more forms of acquiring whose onsets occurred on average in their middle 30’s.

Another explanation is that some people who hoard engage in excessive acquisition, but do not recognize it. The frequency of excessive acquisition reported by family informants of people meeting our criteria for significant hoarding was nearly 95% in the present study compared to 85% for self-reported excessive acquiring, indicating that people who hoard might under-report their acquisition. Research suggests that individuals who hoard often lack insight regarding the behavior (Frost & Gross, 1993; Samuels et al., 2002; Tolin et al., 2007), and anecdotally, we have seen some hoarding patients who initially claimed to have no problems with acquisition only to have such problems become apparent later in therapy. Sometimes people who hoard control their acquisition urges by avoiding the contextual cues that unleash their acquisitive behavior. This can work for a period of time and may lead to the belief that they do not have a problem with acquisition. Usually the avoidance strategy fails because acquisition cues are ubiquitous in U.S. culture. In such cases, it is likely that these people acquired excessively in the past, but were not doing so at the time of the study. Investigations into these possibilities are needed.

Nonetheless, it is possible that there are two forms of hoarding, an acquiring form into which most people fall and a less frequent non-acquiring type. Differences between these types may tell us something about the nature of hoarding. Findings from the current study suggest that any form of excessive acquiring is associated with more severe hoarding, including clutter, difficulty discarding, distress, and interference. Furthermore, hoarders who engage in both buying and acquisition of free things generally have more severe symptoms than those who only acquire through one method. In addition, excessive acquisition was associated with greater psychopathology more generally, including OCD symptoms, depression, anxiety, and stress. Indecisiveness was also greater among participants with excessive acquisition. In sum, the presence of excessive acquisition in hoarding was associated with more severe symptoms and greater co-morbidity, and in some cases experiencing both types of excessive acquisition was associated with more severe symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, stress, OCD) than experiencing only one. Hoarding without excessive acquisition appears to be a milder form of the problem and is associated with less co-morbidity.

While the age differences were statistically significant, the no acquisition group participants were only three years older than participants in the other two groups. Such a small difference is unlikely to be clinically meaningful.

Any form of excessive acquisition was associated with an earlier onset of symptoms. This may be understandable in that without excessive acquisition, clutter takes longer to accumulate. Interestingly, only the excessive acquisition of free things predicted onset independently, suggesting that it may be more important with respect to onset of hoarding. What distinguishes acquiring of free versus bought items is not clear from this study but from a developmental psychopathology perspective, these two forms of hoarding may develop differently and require different treatment emphases.

Compulsive buying has been the subject of considerable research in recent years, but little attention has been paid to the excessive acquisition of free things, and few studies have assessed this behavior. Several early reports found varying patterns of correlation for the acquisition of free things and excessive buying, particularly regarding culturally sanctioned attitudes like materialism (Frost et al., 2007), but findings provided insufficient information to inform our understanding of hoarding. Though there is considerable overlap between compulsive buying and the excessive acquisition of free things, the findings from this study suggest that the compulsive acquisition of free things adds significantly and independently to the prediction of hoarding severity and indecisiveness, among people with hoarding problems. In contrast to excessive buying, acquiring many free things was not affected by gender, but it was correlated with income (people with lower income acquired more free things), suggesting that economic status may play a role in acquiring and in the severity of hoarding and other pathology, although there were no differences between acquisition groups on income.

One implication of these findings is the importance of measurement in studies of hoarding. Unidimensional measures that do not assess the separate components of hoarding may not adequately capture the phenomena. Separate assessment of each dimension (acquisition including both buying and free items, difficulty discarding, clutter) is imperative at this early stage of research to best understand the problem. We suggest that many existing general measures of hoarding (e.g., the hoarding item of the YBOCS checklist) do not adequately assess important dimensions of hoarding. While they may be useful for detecting hoarding in a general sample, their ability to improve our understanding of its psychopathology or aid in treatment is limited.

There are several clinical implications to these findings. First, the high frequency of excessive acquisition in hoarding indicates that it must be addressed in treatment. Unless acquisition is curtailed, progress on clearing clutter will be hampered. Second, acquisition of free items appears to differ from excessive buying and may have different causal factors and require different interventions.

Finally, these findings raise questions for how disorders like compulsive buying are conceptualized. Is compulsive buying a disorder separate from hoarding? While the vast majority of people with hoarding problems acquire excessively, only about half of compulsive buyers suffer from difficulty discarding or excessive clutter (Mueller et al., 2007). If someone engages in both, as the majority of people with hoarding do, should they receive two separate diagnoses –acquiring and hoarding? Compulsive hoarding, compulsive buying, the excessive acquisition of free things, and perhaps kleptomania may all be part of a larger construct/disorder linked with attachment to possessions. Future research is needed to determine the similarities and differences among these forms of possession obsession.

Several limitations qualify the conclusions to be drawn from this study. First, the internet-derived sample of people with hoarding problems may differ from the entire population of people with hoarding problems. For instance, older adults with less computer access and comfort may be underrepresented. Further, people with hoarding problems have frequently been described as having limited insight, yet volunteering for this study required a certain degree of recognition of the problem. It isn’t quite clear how the absence of insight would be related to excessive acquisition. Data from the family member sample would be less likely to be affected by this bias. Though limited, the acquisition findings from family members suggests even higher rates of excessive acquisition than the data provided by hoarding sufferers themselves. A second limitation of the sample was the high percentage of women. Recruitment for this study may have resulted in an overrepresentation of women in the sample. While most studies of compulsive hoarding enroll more women than men, recent findings suggest a more equal gender distribution (Samuels et al., 2008). Finally, the findings of this study relied on internet based self-report questionnaires which may not be entirely consistent with interview based measures. Future studies are needed examining these issues with interview and observation-based measures.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH068008 and MH068007 (Frost and Steketee), R01 MH074934 (Tolin), and R21 MH068539 (Steketee). Oxford University Press supplied copies of a book used in a raffle for participants. The authors thank Dr. Nicholas Maltby for his technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Mckay D, Taylor S. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Subtypes and spectrum conditions. New York: Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, Tx: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cermele JA, Melendez-Pallitto L, Pandina GJ. Intervention in Compulsive Hoarding: A Case Study. Behavior Modification. 2001;25(2):214–232. doi: 10.1177/0145445501252003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MR. Operant hoarding; A new paradigm for the study of self-control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1990;53(2):247–261. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1990.53-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, Frost RO, Heimberg RG. Hoarding behaviors in a large college sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:179–194. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damecour CL, Charron M. Hoarding: A Symptom, Not a Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(5):267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond LM, Turner J, Reid S. Diogenes’ syndrome – a load of old rubbish? . Irish Journal of Psychiatric Medicine. 1996;14(3):99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson GA, Faber RJ, de Zwaan M. Compulsive buying: Descriptive characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994;55:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PB. ‘The bowerbird symptom’: a case of severe hoarding of possessions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:597–600. doi: 10.3109/00048679709065083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Lieberg S, Langer R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, Salkovskis PM. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:485–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Gross RC. The hoarding of possessions. Research and Therapy. 1993;31:367–381. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90094-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Hartl TL. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:341–350. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Hartl T, Christian R, Williams N. The value of possessions in compulsive hoarding: Patterns of use and attachment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:897–902. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00043-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Kim HJ, Morris C, Bloss C, Murray-Close M, Steketee G. Hoarding, compulsive buying and reasons for saving. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Kyrios M, McCarthy KD, Mathews Y. Self-ambivalence and attachment to possessions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2007;21:232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Meagher BM, Riskind JH. Obsessive-compulsive features in pathological lottery and scratch-ticket gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2001;17:5–19. doi: 10.1023/a:1016636214258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: Saving Inventory-Revised. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:1163–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF, Renaud S. Development and validation of the Clutter Image Raging. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2008;30:180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Shows DL. The nature and measurement of compulsive indecisiveness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:683–692. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90121-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams LF. Mood, personality disorder symptoms and disability in obsessive compulsive hoarders: A comparison with clinical and nonclinical controls. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams L. Compulsive buying, compulsive hoarding, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Youngren VR, Mallya GK. The threat of the housing inspector: A case of hoarding. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1999;6:270–278. doi: 10.3109/10673229909000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D. Compulsive Hoarding. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1987;41(3):409–416. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1987.41.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Witzum E, Levy A. Hoarding as a Psychiatric Symptom. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1990;51:417–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve KW, Curtis KL, Bianchini KJ. Personality disorder masquerading as dementia: A case of apparent Diogenes syndrome. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):703–705. doi: 10.1002/gps.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl TL, Frost RO. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of compulsive hoarding: a multiple baseline experimental case study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-212): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Frank RG. The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:861–873. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Barber C. The association between chronic medical conditions and work impairment. In: Rossi AC, editor. Caring and doing for other: Social responsibility in the domains of family, work, and community. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001. pp. 403–426. [Google Scholar]

- Koran LM, Faber RJ, Aboujaoude E, Large MD, Serpe RT. Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying behavior in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1806–1812. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Olson J, Banaji M. Psychological research online: report of board of scientific affairs’ advisory group on the conduct of research on the Internet. American Psychologist. 2004;59:105–117. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrios M, Frost RO, Steketee G. Cognitions in compulsive buying and acquisition. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Lejoyeux M, Bailly F, Moula H. Study of compulsive buying in patients presenting obsessive-compulsive disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005;46:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Sydney: Psychology Foundation; 1995 . [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Keck PE, Pope HG, Smith JMR, Strakowski SM. Compulsive buying: A report of 20 cases. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994;55:242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller A, Mueller U, Albert P, Mertens C, Silbermann A, Mitchell JE, de Zwann M. Hoarding in a compulsive buying sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2754–2763. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Stelian J, Wagner J. Diogenes syndrome and hoarding in the elderly: Case Reports. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences. 1999;36(1):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, Cullen BA, Riddle MA, Liang KY, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels J, Bienvenu OJ, Riddle MA, Cullen BA, Grados MA, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G. Hoarding in obsessive compulsive disorder: Results from a case-control study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:517–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S. Is compulsive hoarding a genetically and neurobiologically discrete syndrome? Implications for diagnostic classification. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:380–384. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R, Tallis F. Obsessive-compulsive hoarding: A cognitive-behavioural approach. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1996;24:209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost RO, Kim HJ. Hoarding by elderly people. Health & Social Work. 2001;26:176–184. doi: 10.1093/hsw/26.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost R. Compulsive hoarding: Current status of the research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:905–927. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost RO. Compulsive hoarding and acquiring: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost RO, Kyrios M. Beliefs about possessions among compulsive hoarders. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:467–479. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ND. Hoarding: Eccentricity or Pathology: When to Intervene? . Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1997;29(1):45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Fitch KE, Frost RO, Steketee G. Insight in compulsive hoarding: A survey of family and friends. 2007 Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007a;45:1461–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. A brief interview for assessing compulsive hoarding: The Hoarding Rating Scale. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.001. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Fitch KE. Family burden of compulsive hoarding: Results of an Internet survey. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Gray KD, Fitch KE. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Research. 2008;160:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Kiehl KA, Worhunsky P, Book GA, Maltby N. An exploratory study of the neural mechanisms of decision-making in compulsive hoarding. 2007 doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003371. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vostanis P, Dean C. Self-neglect in adult life. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;161:265–267. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]