Abstract

The PduX enzyme of Salmonella enterica is an l-threonine kinase used for the de novo synthesis of coenzyme B12 and the assimilation of cobyric acid. PduX with an N-terminal histidine tag (His8-PduX) was produced in Esch e richia coli and purified. The recombinant enzyme was soluble and active. Kinetic analysis indicated a steady-state Ordered Bi Bi complex mechanism in which ATP is the first substrate to bind. Based on a multiple sequence alignment of PduX homologues and other GHMP (galactokinase, homoserine kinase, mevalonate kinase, and phosphomevalonate kinase) family members, 14 PduX variants having changes at 10 conserved serine/threonine and aspartate/glutamate sites were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. Each variant was produced in E. coli and purified. Comparison of the circular dichroism spectra and kinetic properties of the PduX variants with those of the wild-type enzyme indicated that Glu-24 and Asp-135 are needed for proper folding, Ser-99 and Glu-132 are used for ATP binding, and Ser-253 and Ser-255 are critical to l-threonine binding whereas Ser-100 is essential to catalysis, but its precise role is uncertain. The studies reported here are the first to investigate the kinetic and catalytic mechanisms of l-threonine kinase from any organism.

The B12 coenzymes (adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl)2 and methylcobalamin) are the largest cofactors known in biology. They are essential for human health and have important metabolic roles in many microbes (1, 2). The B12 coenzymes are synthesized de novo only by certain prokaryotes and from corrinoid precursors by a broader range of organisms (1, 2). De novo synthesis by prokaryotes is the ultimate source of B12, and this process has been extensively studied because of its importance to diverse biological forms and to the commercial production of B12 as a dietary supplement (1). Salmonella enterica is an important model organism for studies of B12 synthesis (3, 4). This organism carries out de novo synthesis under anaerobic conditions and assimilates corrinoids such as cobinamide and cobyric acid (Cby) under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (3, 5). We recently showed that the PduX enzyme of S. enterica is an l-threonine (l-Thr) kinase, which is required for the de novo synthesis of AdoCbl and methylcobalamin and the assimilation of Cby (6). PduX catalyzes the conversion of l-Thr and ATP to ADP and l-threonine-O-3-phosphate (l-Thr-P), a required building block for the de novo synthesis of B12 (Fig. 1) (6). By sequence similarity, the PduX enzyme of S. enterica belongs to the galactokinase, homoserine kinase, mevalonate kinase, and phosphomevalonate kinase (GHMP) family (7), which is a novel family of kinases found in metabolic pathways of small molecules. Although there have been no three-dimensional structures of PduX or other l-Thr kinases reported to date, the crystal structures of several GHMP kinases have been solved (8–22). These structures reveal a unique kinase fold and a novel nucleotide-binding mode that are conserved among members of the GHMP kinase family. Members also contain three common sequence motifs consisting of about 10–15 contiguous amino acids (9, 23). Motif I is at the N-terminal region, and its function is uncertain. Motif II is the most conserved with a typical sequence of Pro-X-X-X-Gly-Leu-X-Ser-Ser-Ala. This region is involved in nucleotide binding and distinguishes the GHMP family from other protein kinase families. Motif III is near the C terminus and contains a small glycine-rich loop that appears well positioned to interact with substrate that is phosphorylated by ATP (24). However, there are highly divergent sequences outside these three motifs, and modes of oligomerization, substrate binding, and catalytic mechanism vary among different GHMP family members (14).

FIGURE 1.

Roles of PduX in B12 synthesis in S. enterica. PduX is required for both the de novo synthesis of AdoCbl and methylcobalamin (MeCbl) and the assimilation of cobyric acid. AdoCbl is required for growth of S. enterica on 1,2-PD and ethanolamine as well for the activity of the MetH methionine synthase that converts homocysteine to methionine. Btu, B12 uptake system; Cbi, cobinamide; AdoCbi, adenosylcobinamide; AdoCby, adenosylcobyric acid; AdoCbi-P, adenosylcobinamide phosphate; AP-P, (R)-1-amino-2-propanol-O-2-phosphate.

Based on structural and biochemical data, members of the GHMP family are subdivided into two groups depending on their catalytic mechanisms. In the first group, which includes rat mevalonate kinase, the crystal structure shows an aspartate residue in the active site positioned to act as a catalytic base that abstracts a proton from the substrate hydroxyl group. In addition, there is a lysine residue that is thought to reduce the pKa of the substrate hydroxyl group and to stabilize the pentacoordinated γ-phosphoryl group of ATP (18). In the second group, such as Escherichia coli homoserine kinase, there appears to be no suitable residue positioned to act as a catalytic base. Consequently it has been hypothesized that homoserine kinase achieves catalysis through transition state stabilization alone (14).

In the present study we investigated the catalytic mechanism of PduX by a series of kinetic studies and mutational analyses of 10 invariant serine/threonine and aspartate/glutamate residues. Results indicate a steady-state Ordered Bi Bi mechanism in which ATP binds first. We also identified several amino acids critical to substrate binding and catalysis. To our knowledge, these are the first reported studies on the catalytic mechanism of l-Thr kinase from any organism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Reagents

l-Thr ((2S,3R)-2-amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid), AMP-PNP, l-Thr-P, l-valine (l-Val), nucleoside triphosphates, and nucleoside diphosphates were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Pefabloc SC PLUS was purchased from ICN Biomedicals Inc. (Aurora, OH). Other chemicals were from Fisher Scientific.

Cloning Expression and Purification of His8-PduX and Native PduX

PCR was used to amplify the pduX coding sequence from pEM55 (25). The forward primer for fusing eight histidines to the N terminus was 5′-GCCGCCAGATCTATGAAACACCATCACCATCATCACCACCATATGCGCGCACACTATTCGTACC-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-GCCGCCAAGCTTATCACTGCAGTTTGACCCCGCC-3′. The cloning procedure and the protein production and purification procedure were carried out as described previously (6). For removal of the N-terminal His8 tag and purification of the non-tagged PduX protein, we used TAGZyme DAPase Enzyme (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. This procedure produced native PduX lacking the N-terminal methionine.

Kinase Activity Assay

The activity of PduX was measured by using an ADP Quest assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (DiscoverRx, Fremont, CA) as described previously (6). To minimize background fluorescence, 96-well black microplates were used (Greiner Bio-one, Frickenhausen, Germany). For kinetic studies, the concentrations of certain assay components were varied as indicated in the text. The data addressing the kinetic mechanism were analyzed by double reciprocal plots. Km and Vmax values for PduX variants were calculated by nonlinear curve fitting using the program GraFit (Erithacus Software Ltd.).

Site-directed Mutagenesis of His8-PduX

Mutations were introduced into the His8-PduX-pTA925 (6) construct using the QuikChange II-E Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Briefly PCR was used to amplify the entire plasmid from two complementary primers that both contained the desired mutation. The template plasmid was then digested with DpnI and transformed into E. coli XL-1 Blue. Pure cultures were prepared from selected transformants, and the plasmids were purified. Clones with the expected DNA sequence were used for further study. All mutant PduX proteins were produced and purified by the same method as used for the wild type.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectra

CD spectra of the mutants used in this study were collected using a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter (cell length = 1 cm). The samples contained enzyme (4.0 μm) and K2HPO4 (10 mm). CD data were collected from 190 to 250 nm with a scanning speed of 50 nm/min, resolution of 0.2 nm, bandwidth of 1.0 nm, sensitivity of 20 millidegrees, and response of 8 s at room temperature. CD data were analyzed by the program JFIT.

Protein Stability by Urea Unfolding

Protein unfolding by urea was measured by steady-state fluorescence with a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer at 25 °C. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 295 and 320 nm. Protein samples having an absorbance of 0.05 at 295 nm were used for the unfolding studies. Aliquots of 10 m urea were added to the samples. After correction for dilution of the sample, the fluorescence data were fitted with the following equations assuming the linear dependence of ΔGUN0(d) on denaturant concentration (26): F(d) = [1 − fU(d)][FN,0 − SN[d]] + fU(d)[FU,0 − SU[d]] where fU(d) = exp(−ΔGUN0(d)/RT)/[1 + exp(−ΔGUN0(d)/RT)] and ΔGUN0(d) = ΔGUN0 − m[d]. ΔGUN0 is the unfolding free energy. m is an index of responsiveness of the protein to unfolding by the denaturant. SN and SU are the slopes of the fluorescence intensity versus [d] for the native and unfolded states, respectively. FN,0 and FU,0 are the fluorescence intensities of the native and unfolded states, respectively, in the absence of denaturant. fu is the percent unfolded protein. A nonlinear least squares approach was used to obtain ΔGUN0.

Growth Tests for in Vivo Function of PduX

The minimal medium used was no-carbon E medium (27) supplemented with 0.4% 1,2-propanediol (1,2-PD), 1 mm MgSO4, 50 μm ferric citrate, 1 μm 5,6-dimethylbenzimidizole, and 3 mm each valine, isoleucine, leucine, and threonine. To prepare the inocula, 2-ml cultures were made using Luria-Bertani medium. Cultures were incubated overnight at 37 °C, and then cells were collected by centrifugation and suspended in growth curve medium. Media were inoculated to a density of 0.15 absorbance units, and the cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm using a BioTek Synergy microplate reader and 48-well flat bottom plates (Falcon) as described previously (28).

DNA Sequencing

DNA sequencing was carried out by Iowa State University (DNA facility of Iowa State University Office of Biotechnology) using automated sequencing equipment from Applied Biosystems Inc.

RESULTS

The PduX l-Thr Kinase Reaction Proceeds via a Steady-state Ordered Bi Bi Mechanism

For a bisubstrate reaction, there are two classes of kinetic mechanisms: one involves a ternary complex of both substrates and the enzyme, and the other is the “ping-pong” mechanism (29). In the ping-pong model, one substrate binds to the enzyme, and then a chemical change occurs such as covalent modification of the enzyme. Next the first product is released, and the second substrate binds, often receiving the chemical group from the enzyme. A diagnostic feature of this mechanism is that when the concentration of one substrate is fixed and the other is varied double reciprocal plots of rate versus concentration of the variable substrate will be parallel for different fixed substrate concentrations (29, 30). Kinetic analyses of His8-PduX showed that such lines were not parallel but converged, arguing against the ping-pong mechanism (Fig. 2). The data in Fig. 2 also exclude the rapid equilibrium Ordered Bi Bi mechanism because in this case lines would intersect at the y axis for plots of 1/v versus 1/B (l-Thr) at fixed various fixed concentrations of the first substrate to bind (31). Hence the PduX reaction most likely proceeds via a ternary complex mechanism in which the enzyme binds to both substrates before a chemical reaction occurs.

FIGURE 2.

Initial rate study of the PduX reaction. Double reciprocal plots of rate versus substrate concentration with one substrate varied and the other held at fixed levels are shown. The reaction conditions were as follows: 10 nm PduX enzyme and ATP and l-Thr concentrations as indicated. Standard assay mixtures contained 15 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 20 mm NaCl, and 10 mm MgCl2 in a total volume of 0.1 ml. The values and error bars shown are based on three replicates.

There are three possible ternary complex mechanisms, one random and two ordered. In a random mechanism, either of the substrates may bind first, and the binding of one may or may not influence the binding of the other. In an ordered mechanism, binding of the first substrate is a prerequisite for binding of the second substrate (30).

A number of kinetic methods have been used over the past 50 years to distinguish between random and ordered kinetic mechanisms. These protocols include the use of isotope exchange (32), dead-end competitive inhibitors (33, 34), and product inhibition experiments (35, 36). Here the latter two methods were used to investigate the kinetic mechanism of PduX. AMP-PMP and l-Val were used as competitive dead-end inhibitors versus ATP and l-Thr, respectively. AMP-PNP was found to be a competitive inhibitor of ATP and a noncompetitive inhibitor of l-Thr (Fig. 3). On the other hand, l-Val was a competitive inhibitor of l-Thr and an uncompetitive inhibitor of ATP (Fig. 4). These findings serve to eliminate the rapid equilibrium Random Bi Bi mechanism as a pathway for substrate interaction in the PduX reaction. In the random mechanism, a competitive inhibitor for either substrate is a noncompetitive inhibitor for the other substrate. For the Ordered Bi Bi kinetic mechanism, a similar inhibition pattern is observed for a dead-end competitive inhibitor for the first substrate to bind. On the other hand, a competitive inhibitor for the second substrate to add to the enzyme will exhibit uncompetitive inhibition relative to the first substrate. The latter pattern is precisely the type of inhibition observed with the PduX l-Thr kinase as illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4. Thus, an ordered mechanism in which ATP binds first is indicated. The unique rate equation for the Ordered Bi Bi mechanism using a competitive inhibitor for substrate B is depicted in Equation 1.

|

where v, Vm, Ka, Kb, Kia, Ki, A, B, and I represent initial velocity, maximal velocity, Michaelis constant for substrate A, Michaelis constant for substrate B, dissociation constant for substrate A, inhibition constant for the dead-end complex (enzyme-ATP-l-Val), substrate A, substrate B, and competitive inhibitor for substrate B, respectively.

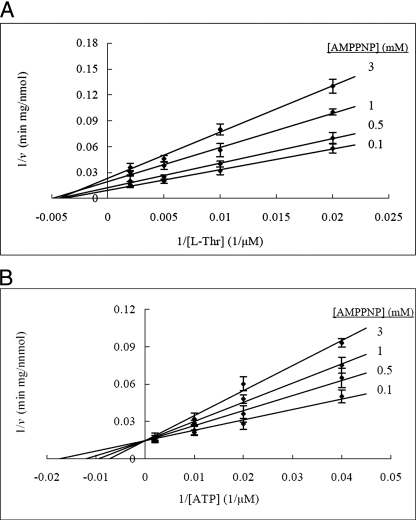

FIGURE 3.

Kinetic analysis of dead-end inhibition by the ATP analog AMP-PNP. A, AMP-PNP is a noncompetitive inhibitor of l-Thr in the PduX reaction. ATP concentration was held at 2 mm. B, AMP-PNP is a competitive inhibitor of ATP in the PduX reaction. l-Thr concentration was held at 5 mm. The reaction conditions were the same as those for the standard assay. The values and error bars shown are based on three replicates.

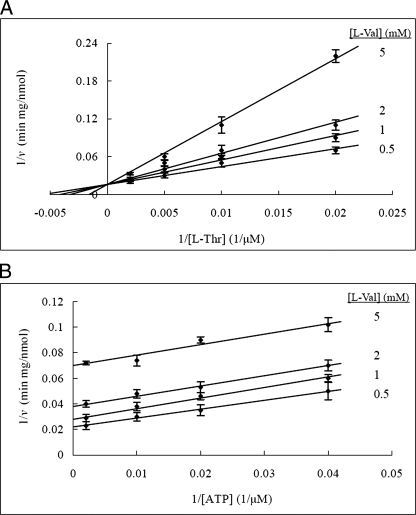

FIGURE 4.

Kinetic analysis of dead-end inhibition by the l-threonine analog l-valine. A, l-Val is a competitive inhibitor of l-Thr in the PduX reaction. ATP concentration was held at 100 μm. B, l-Val is an uncompetitive inhibitor of ATP in the PduX reaction. l-Thr concentration was held at 300 μm. The reaction conditions were the same as those for the standard assay. The values and error bars shown are based on three replicates.

Information about the order of substrate binding (as well as the formation of abortive complexes) can also be obtained by product inhibition studies (29, 33, 36). Therefore, we examined the effect of l-Thr-P on the PduX reaction over a range of concentrations (Fig. 5). l-Thr phosphate was noncompetitive versus both ATP and l-Thr. If the reaction proceeded by a random mechanism, l-Thr-P would be a competitive inhibitor of both substrates. If a ping-pong mechanism was used, l-Thr-P would be a competitive inhibitor versus the first substrate to bind (ATP). Hence random ternary complex and ping-pong mechanisms are inconsistent with the observed pattern of product inhibition that supports an ordered mechanism. Competitive inhibition is also observed in an ordered mechanism between the final product released and the first substrate to bind because both interact with the same form of the enzyme (30). Because l-Thr-P was a noncompetitive inhibitor with respect to both l-Thr and ATP as shown, we conclude that l-Thr-P is the first product released. This means that ADP must be the second product to be released, and symmetry suggests that ATP is the first substrate bound supporting the dead-end inhibitor studies described above. Slope and intercept replots of l-Thr-P inhibition were linear versus ATP and l-Thr indicating that abortive complexes were not significant under the assay conditions used (not shown). Thus, both dead-end inhibitor and product inhibition studies indicate that the PduX l-Thr kinase uses a steady-state Ordered Bi Bi mechanism (Fig. 6). The effects of the other product of the PduX reaction (ADP) as an inhibitor could not be assessed using the coupled enzyme assay system as ADP is a substrate for the coupling enzyme.

FIGURE 5.

Kinetic analysis of product inhibition by l-Thr-P. A, l-Thr-P is a noncompetitive inhibitor of l-Thr in the PduX reaction. ATP concentration was held at 2 mm. B, l-Thr-P is a noncompetitive inhibitor of ATP in the PduX reaction. l-Thr concentration was held at 5 mm. The reaction conditions were the same as those for the standard assay. The values and error bars shown are based on three replicates.

FIGURE 6.

Kinetic mechanism of PduX l-Thr kinase. The kinetic mechanism of PduX is an ordered ternary complex mechanism with ATP binding first.

Selection of Mutagenesis Targets

The choice of the appropriate amino acid targets for site-directed mutagenesis was based on sequence comparisons among related enzymes and previous mutation analysis on other members of GHMP family (37–40). Highly conserved residues in all members of the GHMP family are likely to participate in the common steps of catalysis, whereas residues that are conserved within one family but are different in others are candidates for specific interactions with the substrates. The amino acid sequences of 18 PduX homologues, which are predicted to function in B12 synthesis based on their location in operons involved in B12 synthesis or use (7), were aligned by using the ClustalX program. Four highly conserved motifs were identified (Fig. 7). Motif I of PduX occurs in approximately the same place as the non-ATP substrate-binding site in the other family members, but the sequence is quite different. Therefore, motif I of PduX may form part of the l-Thr-binding site. Motif II is well conserved throughout the GHMP family and interacts with the phosphates of ATP. Motif III is also well conserved across the GHMP family and is close to the substrate-binding sites. Motif IV (which is located between motifs II and III of the GHMP family) is unique to PduX. Because it is near the ATP-binding motif, it is possible that this motif forms part of the active site or ATP-binding site.

FIGURE 7.

Motifs found in a multiple sequence alignment of PduX and homologues. A multiple sequence alignment identified four conserved motifs among PduX homologues. The corresponding motif in the GHMP family is indicated. Motif four is characteristic of PduX. Motif I is only weakly conserved. Deduced amino acid sequences of 18 PduX homologues were aligned using the program ClustalX. Residue numbering corresponds to the PduX enzyme of Salmonella. Invariant residues are marked by stars and highlighted with black boxes and white font. The abbreviations for organisms in sequence after S. enterica are Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Photorhabdus luminescens, Yersinia enterocolitica, Listeria welshimeri, Alkaliphilus metalliredigens, Heliobacterium modesticaldum, Thermosinus carboxydivorans, Moorella thermoacetica, Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans, Natranaerobius thermophilus, Desulfitobacterium hafniense, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Actinoplanes friuliensis, Streptococcus sanguinis, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Clostridium botulinum.

To investigate the mechanism of PduX, we carried out site-directed mutagenesis of these four conserved motifs. Given that catalytic and substrate-binding functions of carboxylate side chains are well documented for several GHMP family enzymes (37, 40), we chose to investigate two conserved glutamates (Glu-24 and Glu-132) and two invariant aspartates (Asp-103 and Asp-135) that are located in the highly conserved motifs (Fig. 7). Each residue was replaced with alanine and its isosteric substitution (glutamine replaces glutamate and asparagine replaces aspartate).

There is also precedent for participation of hydroxyl groups from serine or threonine in substrate binding and/or catalysis in GHMP family members (14, 18, 38, 39). A proposed mechanistic role for such residues is H-bonding to oxygen atoms of the ATP phosphoryl chain (9, 18, 21). Elimination of side chains that function in phosphoryl chain orientation by hydrogen bonding interactions can correlate with large diminutions in catalytic rate (38, 39). From the sequence alignment shown in Fig. 7, we found four invariant serine residues (Ser-99, Ser-100, Ser-253, and Ser-255) and two conserved threonine residues (Thr-101 and Thr-134) in highly conserved motifs (Fig. 7). We replaced these residues with alanines. After verifying their DNA sequence, each of the 14 PduX variants was purified and analyzed for structural integrity and kinetic properties.

Structural Integrity of PduX Variants

We used CD spectra to detect protein secondary structure changes caused by amino acid replacements. CD data were analyzed and fitted by the JFIT program. The wild-type CD spectrum shows the PduX has 67.01% helical, 19.30% sheet, and 13.69% coil structure (Table 1). This result is consistent with the previously solved crystal structures of GHMP family kinases that contain a large proportion of helical structures (9, 17, 18). The CD spectra of the PduX variants were compared with that of the wild-type enzyme (Table 1). Mutations E24A and D135A resulted in a large decrease in helical structure (E24A drops to 54.27% and D135A decreases to 48.05%) indicating that these two conserved sites might be involved in proper folding of PduX enzyme. Other PduX variants showed no obvious changes in the CD spectra indicating that the mutations did not lead to major changes in folding.

TABLE 1.

CD fitted data and unfolding free energy of PduX variants

| Helix | Sheet | Coil | R factor | ΔGUN,25 °C0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | kcal/mol | |

| Wild type | 67.0 ± 3.77 | 19.30 ± 1.39 | 13.69 ± 0.98 | 8.57 ± 0.44 | 6.32 ± 0.43 |

| E24Q | 64.43 ± 5.91 | 20.33 ± 1.99 | 15.24 ± 0.41 | 6.08 ± 0.10 | 5.07 ± 0.30 |

| E24A | 54.27 ± 5.98 | 18.59 ± 0.77 | 27.14 ± 0.41 | 8.25 ± 0.46 | 1.78 ± 0.20 |

| S99A | 66.20 ± 4.45 | 19.61 ± 1.57 | 14.19 ± 0.53 | 7.43 ± 0.27 | 6.09 ± 0.57 |

| S100A | 65.17 ± 2.50 | 25.66 ± 0.78 | 9.17 ± 0.13 | 7.13 ± 0.14 | 6.01 ± 0.44 |

| T101A | 68.27 ± 3.76 | 22.76 ± 2.56 | 8.97 ± 0.92 | 7.35 ± 0.24 | 5.87 ± 0.36 |

| D103N | 63.22 ± 4.86 | 20.52 ± 0.94 | 16.26 ± 0.46 | 7.36 ± 0.25 | 6.18 ± 0.59 |

| D103A | 65.04 ± 3.69 | 20.72 ± 0.96 | 14.24 ± 0.69 | 8.37 ± 0.86 | 6.10 ± 0.49 |

| E132Q | 68.26 ± 3.98 | 22.08 ± 1.47 | 9.66 ± 0.73 | 9.45 ± 0.72 | 5.97 ± 0.42 |

| E132A | 68.41 ± 2.96 | 15.65 ± 2.23 | 15.94 ± 0.49 | 9.45 ± 0.30 | 5.73 ± 0.61 |

| T134A | 66.96 ± 3.64 | 24.20 ± 1.87 | 8.84 ± 0.87 | 7.91 ± 0.92 | 5.91 ± 0.75 |

| D135N | 63.56 ± 2.11 | 19.53 ± 0.53 | 16.91 ± 0.06 | 8.80 ± 0.95 | 4.44 ± 0.35 |

| D135A | 48.05 ± 2.68 | 21.82 ± 1.29 | 30.13 ± 0.76 | 8.18 ± 0.49 | 1.23 ± 0.28 |

| S253A | 66.02 ± 3.12 | 24.11 ± 0.83 | 9.87 ± 0.36 | 8.29 ± 0.21 | 6.21 ± 0.41 |

| S255A | 66.19 ± 3.50 | 17.79 ± 1.08 | 16.02 ± 0.85 | 7.52 ± 0.60 | 5.90 ± 0.59 |

There are six Trp residues in the PduX protein, and five of those are located at the surface based on a structural homology model made with the 3Djigsaw server (41–43). The wild-type protein has a classic pattern of fluorescence changes induced by urea denaturation (Fig. 8). Therefore, urea unfolding studies were used to further assess the stability of the PduX variants. The unfolding free energy of most of the mutants was similar to that of the wild type (Table 1). Consistent with CD analysis, E24A and D135A were found to have a significantly lower unfolding energy and denatured at much lower concentrations of urea (Fig. 8). Thus, both CD and unfolding studies suggest near normal folding by most of the PduX variants studied here.

FIGURE 8.

Stability of PduX variants. To estimate the stability of the PduX variants, unfolding by urea was followed by fluorescence spectroscopy. PduX variants were dissolved in 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.0) and 100 mm NaCl. The urea concentration was increased as indicated, and fluorescence intensity was measured. Data were taken at 25 °C, and ΔGUN0 was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” With the exception of E24A and D135A, most of the mutants exhibited unfolding curves with ΔGUN0 values similar to that of wild type (Table 1). Solid squares, wild type; open diamonds, E24A; solid triangles, D135A.

Kinetic Characterization of pduX Mutants

Using purified enzymes, kinetics constants were determined for the wild-type and mutant PduX enzymes. The purity of wild-type and mutant proteins was about 95% based on SDS-PAGE. Km and kcat values were determined by nonlinear regression with GraFit (Table 2). When the Km values for ATP were determined, saturating levels of l-Thr (5 mm) were added to assay mixtures, and the ATP concentration was varied from 0 to 500 μm. Similarly saturating levels of ATP (2 mm) and varying levels of l-Thr from 0 to 500 μm were used to determine the Km values for l-Thr. There were only small differences between the values of native PduX and His8-tagged PduX indicating that the tag had no major effect on the kinetic parameters (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Kinetics constants for PduX mutants

kcat,ATP is the apparent turnover number derived from experiments in which the ATP concentration was varied. kcat,l-Thr is the apparent turnover number derived when l-Thr was varied. The fixed substrate was used at saturating levels (>10-fold Km). Mean values of kcat and Km were used to calculate kcat/Km. Mutants without measurable activity (E24A, S100A, and D135A) are not shown in this table.

| Km,ATP | Km,l-Thr | kcat,ATP | kcat,l-Thr | kcat/Km,ATP × 10−4 | kcat/Km,l-Thr × 10−4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | min−1 | min−1 | μm−1min−1 | μm−1min−1 | |

| His8-PduX | 55 ± 4 | 127 ± 4 | 2.56 ± 0.16 | 2.62 ± 0.17 | 466 | 206 |

| Native PduX | 54 ± 6 | 146 ± 8 | 2.45 ± 0.12 | 2.56 ± 0.12 | 453 | 175 |

| E24Q | 117 ± 8 | 464 ± 4 | 1.12 ± 0.07 | 1.13 ± 0.05 | 95.6 | 24.4 |

| S99A | 1374 ± 96 | 176 ± 17 | 2.03 ± 0.22 | 1.95 ± 0.18 | 14.8 | 111 |

| T101A | 98 ± 6 | 220 ± 14 | 2.13 ± 0.13 | 2.22 ± 0.17 | 218 | 101 |

| D103N | 141 ± 13 | 184 ± 12 | 2.03 ± 0.21 | 2.15 ± 0.13 | 144 | 117 |

| D103A | 163 ± 11 | 258 ± 18 | 1.88 ± 0.09 | 1.93 ± 0.12 | 116 | 74.9 |

| E132Q | 1264 ± 152 | 144 ± 25 | 1.63 ± 0.08 | 1.55 ± 0.07 | 12.9 | 108 |

| E132A | 1979 ± 213 | 198 ± 23 | 1.23 ± 0.10 | 1.16 ± 0.11 | 6.22 | 58.6 |

| T134A | 87 ± 8 | 142 ± 16 | 2.05 ± 0.15 | 2.12 ± 0.15 | 236 | 149 |

| D135N | 68 ± 6 | 273 ± 9 | 1.04 ± 0.11 | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 154 | 35.2 |

| S253A | 76 ± 6 | 4698 ± 232 | 1.56 ± 0.14 | 1.72 ± 0.09 | 205 | 3.66 |

| S255A | 74 ± 7 | 3708 ± 404 | 1.36 ± 0.17 | 1.43 ± 0.16 | 185 | 3.86 |

Three mutants (E24A, S100A, and D135A) had no activity even with saturating levels of both substrates (2 mm ATP and 5 mm l-Thr), so their kinetic parameters could not be determined. Two of these (E24A and D135A) had abnormal CD spectra indicating improper folding. Six mutants (E24Q, T101A, D103A, D103N, T134A, and D135N) had kinetic parameters similar to those of wild-type PduX. The remaining five mutants had altered kinetic properties compared with wild-type PduX. Mutations S253A and S255A increased the Km for l-Thr more than 30-fold indicating that these residues may be involved in binding of l-Thr. Mutations S99A, E132Q, and E132A, had Km values for ATP more than 20-fold higher than wild type indicating a possible role in ATP binding.

In Vivo Activities of pduX Mutants

S. enterica pduX deletion mutants are impaired for the conversion of Cby acid to AdoCbl; consequently they grow poorly on 1,2-PD minimal medium supplemented with Cby (6). In previous work, we showed that this growth phenotype is corrected by production of PduX from an expression plasmid (6). Here similar experiments were used to assess the in vivo activity of the PduX variants. Three different growth patterns were observed (Fig. 9). E24A, D135A, and S100A were unable to support growth indicating that these three mutants lacked PduX activity in vivo. S253A and S255A grew slowly most likely because of the lower affinity of these variants for l-threonine. The other mutants (E24Q, S99A, T101A, D103N, D103A, E132Q, E132A, T134A, and D134N) grew similarly to the wild type. Although the S99A, E132A, and E132Q variants of PduX exhibited a large increase in Km values for ATP, they still supported normal growth. This may be due to the fact that the Km values of these variants are still in the normal range of ATP concentration within bacterial cells (1–3 mm).

FIGURE 9.

In vivo activities of PduX variants. Cells were grown in minimal 1,2-PD medium (described under “Experimental Procedures”) supplemented with 50 nm cobyric acid. PduX is required for growth under these conditions because it is essential for the conversion of Cby to AdoCbl, a required cofactor for 1,2-PD degradation by S. enterica. Three representative growth patterns are shown in the figure. The PduX variants displaying these patterns are described in the text. Solid diamond, wild type; open triangle, S253A; solid square, S100A.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies of GHMP family members have revealed three kinetic mechanisms depending on the enzyme. The first group uses an ordered mechanism in which ATP is the first substrate to bind and includes galactokinase from rat liver (44), yeast (45), and human (46) and homoserine kinases from E. coli (47) and Methanococcus jannaschii (48). The second group appears to have an ordered mechanism in which the non-ATP substrate binds first and includes broad bean galactokinase (49) and hog liver mevalonate kinase (50). The last group was shown to proceed by a random ternary complex mechanism such as E. coli galactokinase (51) and Streptococcus pneumoniae phosphomevalonate kinase (52). It is interesting that GHMP family members use different kinetic mechanisms despite the existence of highly similar tertiary structures. This suggests that this superfamily interacts with their substrates using analogous chemical and structural features but that their dynamics are quite different. The studies of PduX l-Thr kinase presented here are consistent with an ordered ternary complex mechanism in which ATP binds first and l-Thr binds second. The most likely explanation for an ordered mechanism is that the binding of the first substrate induces a conformational change in the enzyme resulting in the formation of a high affinity binding site for the second substrate.

Prior studies of GHMP family members indicate critical catalytic and substrate binding roles for carboxylate- and hydroxyl-containing side chains (37, 53–55). Here we changed 10 highly conserved amino acids of PduX that have such side chains and tested the effect of these mutations on structure and kinetic parameters. Our alignment results showed that there are four highly conserved motifs in PduX homologues. In motif I, Glu-24 is the only invariant residue, and it is also well conserved in the GHMP family. The replacement of Glu-24 with alanine resulted in large secondary structure changes (about 30 amino acids changed from a helical structure to random coil) and complete loss of activity. Because alanine has a small side chain without any charge or polarity, we made the isosteric substitution of glutamine for Glu-24. This mutant had almost the same secondary structure and had kinetic behavior similar to that of wild type with only a 2-fold decrease in specific activity and a modest increase in apparent Km values for both substrates (2-fold increase for ATP and 3.5-fold increase for l-Thr). These results indicate that Glu-24 is probably involved in folding rather than in having a direct role in catalysis.

Motif II is the most highly conserved motif in the GHMP family. It forms a distinct ATP binding loop not found in other kinase families (23). In this motif, we mutated four sites: Thr-101 and Asp-103 that are only highly conserved in PduX homologues and Ser-99 and Ser-100 that are conserved across the entire GHMP family. None of these mutations caused an obvious change in secondary structure based on CD analyses. T101A showed only a 15% decrease in apparent turnover number and approximately a 2-fold increase in Km for both ATP and l-Thr. Replacement of Asp-103 with alanine or asparagine did not cause a significant change in kinetic parameters. It seems that Thr-101 and Asp-103 have no key functions in substrate binding or catalysis even though they are conserved among PduX homologues. In contrast, mutant S99A had a 25-fold higher Km for ATP, a 1.4-fold higher Km for l-Thr, and 1.2-fold decrease in kcat indicating that Ser-99 is involved in ATP binding. Mutant S100A had no activity at all even with 2 mm ATP (40-fold Km,ATP for wild type). Hence we propose a critical role of the hydroxyl group of Ser-100 in catalysis of the PduX reaction. Ser-100 of PduX corresponds to Ser-145 in human and Ser-121 in yeast mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase. Previous mutagenesis analysis of human mevalonate kinase led to the proposal that Ser-145 functions also as a hydrogen bond donor to a phosphoryl oxygen of bound substrate or product nucleotide (38). In yeast mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase, it was proposed that Ser-121 functions in orienting the phosphoryl chain to optimize the angle of attack on the γ-phosphorus atom of ATP (39). We propose that Ser-100 of PduX has a similar role and serves to orient the γ-phosphate of ATP for reaction with the hydroxyl of l-Thr (14). However, an understanding of the exact function of Ser-100 in the PduX l-Thr kinase reaction will require further studies.

Mutagenesis was also used to examine the function of conserved motif III in PduX. S253A and S255A both showed large increases in apparent Km values for l-Thr (37- and 29-fold individually). Because both substitutions had no major impact (less than 2-fold) on turnover rates or the specificity constants for ATP, the large increase in Km,l-thr reflects a significant diminution in l-Thr binding efficiency.

Motif IV is conserved only in the PduX homologues, but the specific sites within this motif that were changed for this study are also well conserved across the GHMP family. Several crystal structures of GHMP members show that a glutamate residue, corresponding to Glu-132 in PduX, coordinates with Mg2+ ion and thus activates the γ-phosphate of ATP (14, 15, 18). When we changed Glu-132 of PduX to alanine or glutamine, the Km value for ATP increased 37- and 23-fold, respectively, with only a minor (less than 1.5-fold) change in the kcat or the kcat/Km for l-Thr. Hence in PduX, Glu-132 plays an important role in substrate binding (and probably binds the Mg-ATP chelate) but a less critical role in the catalytic mechanism. The T134A mutation had little effect on the kinetics of PduX. Motif IV also contains conserved residue Asp-135. Replacement of Asp-135 with alanine caused the loss of both structural integrity and enzyme activity, whereas its substitution with asparagine had little effect (only 2-fold decrease in apparent specificity activity). Hence in PduX, Asp-135 appears to have primarily a structural role.

Within the GHMP kinase family, different members are proposed to use one of two different catalytic mechanisms. Studies on mevalonate kinase and phosphomevalonate kinase have suggested a mechanism involving a conserved aspartate residue as a possible catalytic base whose role is to activate the acceptor hydroxyl group of the substrate. A conserved lysine residue near the acceptor hydroxyl group is proposed to lower its pKa facilitating proton abstraction (15, 17, 18, 24). In contrast, in homoserine kinase, no strong nucleophile sits near the acceptor hydroxyl group. Phosphoryl transfer in homoserine kinase has been suggested to occur by direct nucleophilic attack on the γ-phosphorus atom of ATP by the δ-hydroxyl of homoserine (14). In this proposed mechanism, deprotonation of the donor hydroxyl group is mediated by interaction with the γ-phosphate of ATP (14). In addition, the side chain hydroxyl group of Thr-183 interacts with the β-phosphate of the nucleotide and thus may also help to stabilize the transition state (14). In another GHMP member, galactokinase, there is a conserved Asp-183 positioned to abstract the proton from the hydroxyl group of galactose for its subsequent attack on the γ-phosphorus atom of ATP. Additionally there is an Arg-36 residue that corresponds to the lysine in mevalonate kinase that is hypothesized to lower the pKa of the substrate hydroxyl group (8). However, the role of Asp-183 as a catalytic base for galactokinase has been questioned on the basis of kinetic studies that found little variation in the turnover number and specificity constants with respect to pH and negligible effects on addition of increasing mole fractions of deuterium oxide in place of water (10, 45, 46). These findings suggested that an ionizable group was not directly involved in catalysis (10, 45, 46). In the case of PduX, Asp-135 (which corresponds to the proposed catalytic base of mevalonate kinase) appears to play primarily a structural role because the D135N substitution had little effect on enzyme activity whereas the D135A caused misfolding as described above. Hence the mechanism of PduX may be more like that of homoserine kinase that is proposed to increase catalysis primarily by transition state stabilization (14). A proposed model for the PduX transition state is shown in Fig. 10. In this model, a basic residue or an H-bond acceptor increases the nucleophilicity of the substrate hydroxyl. General acid catalysis stabilizes the transition state and allows formation of the ADP anion as the leaving group. In addition, hydrogen bonding (perhaps to Ser-100 in PduX) and Mg2+ further delocalize the negative charge that develops on the β-phosphate group stabilizing the transition state and enhancing catalysis.

FIGURE 10.

Proposed transition state for the PduX reaction. In this mechanism, “X” is either a catalytic base or a hydrogen bond acceptor that would help stabilize negative charge on the substrate hydroxyl increasing its nucleophilicity. The “Y” represents an acidic group on the enzyme that would stabilize developing negative charge and donate a proton to form the ADP dianion as the leaving group. In addition, the developing negative charge on the β-phosphate would likely be further stabilized by hydrogen bonding and coordination to divalent magnesium ion, which is not shown in the figure. Partial charges (δ) on groups X and Y were omitted because the exact nature of these groups is unknown.

In summary, the four conserved motifs in the PduX subfamily play different roles in the phosphoryl transfer process. Motifs II and IV are mainly for ATP binding whereas motif III is for l-Thr binding. Glu-24 and Asp-135 are needed for proper folding. Collectively the studies presented here help to define the catalytic mechanism of l-Thr kinase, a key enzyme in the de novo synthesis of coenzyme B12, and further expand our understanding of the catalytic properties of the GHMP superfamily.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Protein Facility of the Department of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Molecular Biology, Iowa State University for help with the CD spectroscopy.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB 0616008.

- AdoCbl

- adenosylcobalamin

- Cby

- cobyric acid

- l-Thr-P

- l-threonine-O-3-phosphate

- GHMP

- galactokinase, homoserine kinase, mevalonate kinase, and phosphomevalonate kinase

- AMP-PNP

- adenylyl imidodiphosphate

- CD

- circular dichroism

- 1,2-PD

- 1,2-propanediol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee R. (ed) (1999) Chemistry and Biochemistry of B12, John Wiley and Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider Z., Stroinski A. (1987) Comprehensive B12: Chemistry, Biochemistry, Nutrition, Ecology, Medicine, De Gruyter, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escalante-Semerena J. C. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 4555–4560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth J. R., Lawrence J. G., Rubenfield M., Kieffer-Higgins S., Church G. M. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 3303–3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth J. R., Lawrence J. G., Bobik T. A. (1996) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50, 137–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan C., Bobik T. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 11322–11329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodionov D. A., Vitreschak A. G., Mironov A. A., Gelfand M. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41148–41159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thoden J. B., Holden H. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33305–33311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartley A., Glynn S. E., Barynin V., Baker P. J., Sedelnikova S. E., Verhees C., de Geus D., van der Oost J., Timson D. J., Reece R. J., Rice D. W. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337, 387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoden J. B., Timson D. J., Reece R. J., Holden H. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9662–9670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thoden J. B., Holden H. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32784–32791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thoden J. B., Sellick C. A., Timson D. J., Reece R. J., Holden H. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36905–36911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou T., Daugherty M., Grishin N. V., Osterman A. L., Zhang H. (2000) Structure 8, 1247–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishna S. S., Zhou T., Daugherty M., Osterman A., Zhang H. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 10810–10818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang D., Shipman L. W., Roessner C. A., Scott A. I., Sacchettini J. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9462–9467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreassi J. L., 2nd, Bilder P. W., Vetting M. W., Roderick S. L., Leyh T. S. (2007) Protein Sci. 16, 983–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sgraja T., Smith T. K., Hunter W. N. (2007) BMC Struct. Biol. 7, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu Z., Wang M., Potter D., Miziorko H. M., Kim J. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18134–18142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romanowski M. J., Bonanno J. B., Burley S. K. (2002) Proteins 47, 568–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonanno J. B., Edo C., Eswar N., Pieper U., Romanowski M. J., Ilyin V., Gerchman S. E., Kycia H., Studier F. W., Sali A., Burley S. K. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12896–12901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miallau L., Alphey M. S., Kemp L. E., Leonard G. A., McSweeney S. M., Hecht S., Bacher A., Eisenreich W., Rohdich F., Hunter W. N. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9173–9178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada T., Kuzuyama T., Satoh S., Kuramitsu S., Yokoyama S., Unzai S., Tame J. R., Park S. Y. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30022–30027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bork P., Sander C., Valencia A. (1993) Protein Sci. 2, 31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreassi J. L., 2nd, Leyh T. S. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 14594–14601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bobik T. A., Havemann G. D., Busch R. J., Williams D. S., Aldrich H. C. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 5967–5975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eftink M. R., Ghiron C. A., Kautz R. A., Fox R. O. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 1193–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel H. J., Bonner D. M. (1956) J. Biol. Chem. 218, 97–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Leal N. A., Sampson E. M., Johnson C. L., Havemann G. D., Bobik T. A. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 1589–1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor K. B. (2002) Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanisms, pp. 66–121, Kluwer Academic Publishers,Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leskovac V. (2003) Comprehensive Enzyme Kinetics, pp. 117–208, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers,New York [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fromm H. J. (1975) Initial Rate Enzyme Kinetics, 1st Ed., pp.121–160, Springer-Verlag, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyer P. D. (1959) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 82, 387–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fromm H. J. (1979) Methods Enzymol. 63, 467–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fromm H. J., Zewe V. (1962) J. Biol. Chem. 237, 3027–3032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alberty R. A. (1958) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1777–1782 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fromm H. J., Nelson D. R. (1962) J. Biol. Chem. 237, 215–220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potter D., Miziorko H. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25449–25454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho Y. K., Ríos S. E., Kim J. J., Miziorko H. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12573–12578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krepkiy D. V., Miziorko H. M. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 2671–2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krepkiy D., Miziorko H. M. (2004) Protein Sci. 13, 1875–1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates P. A., Kelley L. A., MacCallum R. M., Sternberg M. J. (2001) Proteins 45, Suppl. 5,39– 46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bates P. A., Sternberg M. J. (1999) Proteins 37, Suppl. 3,47– 54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Contreras-Moreira B., Bates P. A. (2002) Bioinformatics 18, 1141–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ballard F. J. (1966) Biochem. J. 101, 70–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timson D. J., Reece R. J. (2002) Biochimie 84, 265–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Timson D. J., Reece R. J. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 1767–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shames S. L., Wedler F. C. (1984) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 235, 359–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daugherty M., Vonstein V., Overbeek R., Osterman A. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183, 292–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dey P. M. (1983) Eur. J. Biochem. 136, 155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beytia E., Dorsey J. K., Marr J., Cleland W. W., Porter J. W. (1970) J. Biol. Chem. 245, 5450–5458 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gulbinsky J. S., Cleland W. W. (1968) Biochemistry 7, 566–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pilloff D., Dabovic K., Romanowski M. J., Bonanno J. B., Doherty M., Burley S. K., Leyh T. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4510–4515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huo X., Viola R. E. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 16180–16185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huo X., Viola R. E. (1996) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 330, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Potter D., Wojnar J. M., Narasimhan C., Miziorko H. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5741–5746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]