Abstract

We present three cases of patients (at the age of 56 years, 49 years and 74 years respectively) with severe acute pancreatitis (SAP), complicated by intra-abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) and respiratory insufficiency with limitations of mechanical ventilation. The respiratory situation of the patients was significantly improved after decompression laparotomy (DL) and lung protective ventilation was re-achieved. ACS was discussed followed by a short review of the literature. Our cases show that DL may help patients with SAP to recover from severe respiratory failure.

Keywords: Severe acute pancreatitis, Intra-abdominal compartment syndrome, Decompression laparotomy, Intensive care unit, Respiratory failure

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is associated with organ failure leading to a mortality rate of 10%-20% that is often related to respiratory failure. Approximately one third of SAP patients develop respiratory complications[1,2]. In the majority of cases, this lung injury is characterized by an increased permeability of pulmonary microvasculature and subsequent leakage of protein-rich exudates into the alveolar spaces[1]. Furthermore, concomitant diseases, such as intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) defined by intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) greater than 12 mmHg[3], may result in restrictive ventilation disorders and deteriorate the pulmonary situation.

Surgical debridement was the preferred treatment to control necrotizing pancreatitis in the past. However, management of necrotizing pancreatitis has changed since the last decade. The first approach now tends to be non-surgical and relies on conservative strategies including early transfer of patients to intensive care units at specialized centres. Indication for necrosectomy is still given in cases of infected necrosis as well as intestinal infarction, perforation or bleeding, but there is a clear trend towards surgical treatment as late and as rare as possible[2]. In contrast, more and more studies are published promoting decompression laparotomy (DL) for SAP patients developing abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) defined by IAP greater than 20 mmHg associated with new organ failure[3-7]. This procedure can not only prevent critical decrement of intestinal and renal perfusion, but may lead to improvement in the respiratory situation.

We present three patients with SAP and abdominal compartment syndrome, who developed respiratory insufficiency with limitations of mechanical ventilation associated with high peak pressure levels, low tidal volumes and poor Horowitz-indices (pO2/FiO2; HI). The three patients showed a benefit from decompression laparotomy so that ventilation with adequate oxygenation could be re-achieved. Surgery was performed at the Intensive Care Unit of our hospital without transportation of the patients to the operating room.

CASE REPORT

Patient 1

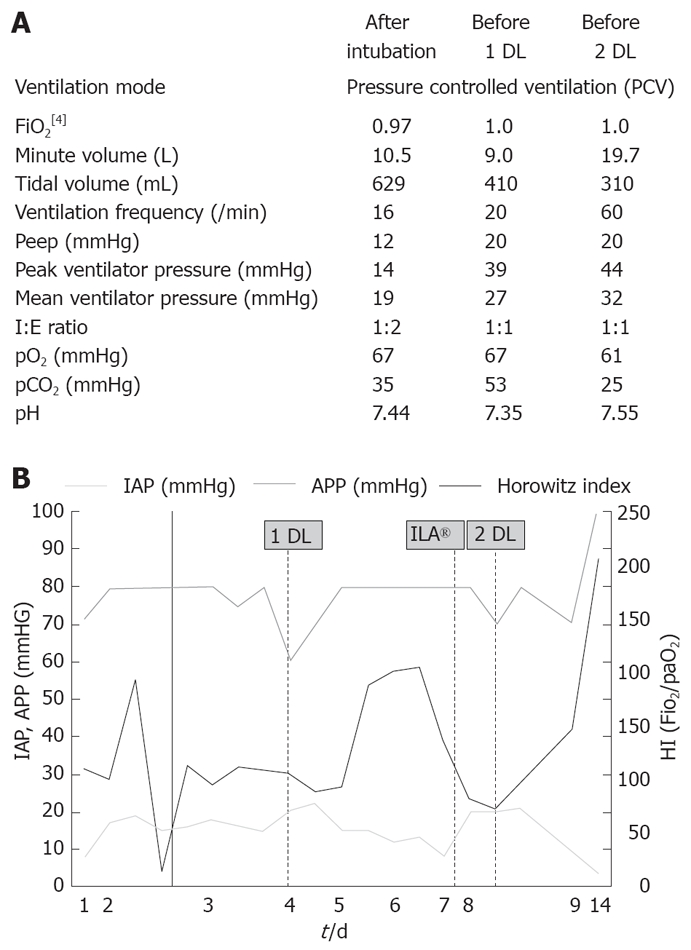

A 56-year-old male electrician was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit of our hospital because of necrotizing pancreatitis. One week prior to admission, he underwent an ambulant gastroduodenoscopy in the referring hospital and resection of pancreatic papilla minor due to misinterpretation as a polyp. Following endoscopy, progredient upper abdominal pain developed with rising serum lipase and CRP levels. Diagnostic procedures including abdominal sonography, CT-scan and endoscopic-retrograde-cholangio-pancreaticography (ERCP) confirmed pancreatitis. At admission, intubation was performed followed by mechanical ventilation because of respiratory insufficiency (Figure 1A). In the next days, fluid resuscitation was performed, and increasing peak inspiratory and mean airway pressures were needed to achieve sufficient oxygenation. Meanwhile, IAP determined by an indwelling transurethral bladder catheter increased. On day 4, criteria for an ACS were fulfilled (Figure 1B). Simultaneously, Horowitz index decreased (75 mmHg) with 100% oxygen, a positive end expiratory pressure of 20 mmHg and a peak inspiratory airway pressure of 39 mmHg. Sonography revealed an elevation of the diaphragm without any movement. On day five, we decided to perform decompression laparotomy to improve pulmonary gas exchange. A median laparotomy of approximately 30 cm was performed. The abdominal cavity was closed with absorbable Vicryl®-Mesh. Postoperative oxygenation improved with decreasing ventilation pressures and chest wall compliance. Nevertheless the respiratory situation deteriorated again with low oxygenation values and hypercapnia, while IAP equally rose. A pumpless extracorporeal lung assist system (ILA®) was installed on day eight, resulting in a marked decrease in pCO2, but the Horowitz index did not improve. Since the IAP values increased again (> 20 mmHg), the laparotomy was extended from xiphoid process to symphysis, thereby leading to a significant improvement in the respiratory situation. Again, the abdominal cavity was closed with Vicryl®-Mesh. During the next days, CT scan-guided retroperitoneal drainage was performed for debridement of pancreatic necrosis. As a result, IAP further decreased (Figure 1B). The patient was successfully weaned, therapy with ILA® system could be quickly terminated and the abdomen healed by secondary wound healing.

Figure 1.

Ventilation adjustment of patient 1 after intubation, before 1 DL and 2 DL (A), and development of IAP, APP and HI in this patient over 14 d of ICU hospitalisation (B). The spotted lines refer time points of the first and second DL as well as installation of ILA®.

Patient 2

A 49-year-old man with morbid obesity (172 cm, 150 kg, BMI = 50.7 kg/m2) presented in the Emergency Department of our hospital for colicky abdominal pain. His past medical history included a limited cardiac function due to ischemic heart disease and recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Laboratory and radiological findings as well as endoscopy revealed biliary pancreatitis. Three days after admission, his respiratory situation worsened and he was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit. Mechanical ventilation had to be initiated. On the second day of intensive care treatment, intra-abdominal inflammation, massive fluid resuscitation (fluid intake about 10 L/d, urine output 1 L/d the first day, up to 7 L/d the next days) and pre-existing obesity led to ACS with a measured IAP above 25 mmHg. Limitations of ventilation therapy with decreased lung and chest compliance prompted us to perform decompression laparotomy. IAP, APP, Horowitz index as well as compliance values significantly improved after surgical therapy and lung protective ventilation could be re-achieved. Secondary wound healing of the open abdomen was improved after vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy (Figure 2B). Unfortunately, the patient developed cardiovascular complications and died of fulminant lung bleeding two weeks later.

Figure 2.

Open abdomen after surgical decompression. A and C: Intra-abdominal drains further reduce intra-abdominal tension; B: Vacuum bondage improves wound healing. A: Patient No. 1; B: Patient No. 2; C: Patient No. 3.

Patient 3

A 74-year-old woman was admitted with post-ERCP pancreatitis after an ERCP was performed for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. She was transferred to our hospital from another hospital due to aggravation of her condition with rising inflammation parameters. On the day of admission, she had to be intubated, mechanical ventilation was started and fluid resuscitation was performed. Within 3 d the HI dramatically dropped with simultaneously increasing peak pressure levels (Figure 3). Under 100% oxygen ventilation, inverse ventilation ratio (2:1), peak pressure of 45 mmHg and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 22 mmHg, and PO2 of 70 mmHg could be achieved. Clinically, she presented with massive abdominal tenderness. IAP-values above 20 mmHg were measured and decompression laparotomy was performed due to respiratory failure. Immediately after the intervention, her respiratory situation improved significantly. During the next days, interventional CT-guided drainage therapy was performed and led to a further decrease in intra-abdominal pressure. Weaning was successful and spontaneous breathing was re-achieved after dilatation tracheotomy and prolonged respiratory therapy due to septic complications. Three months after recovery, the abdominal laparotomy wound was closed along with elective cholecystectomy.

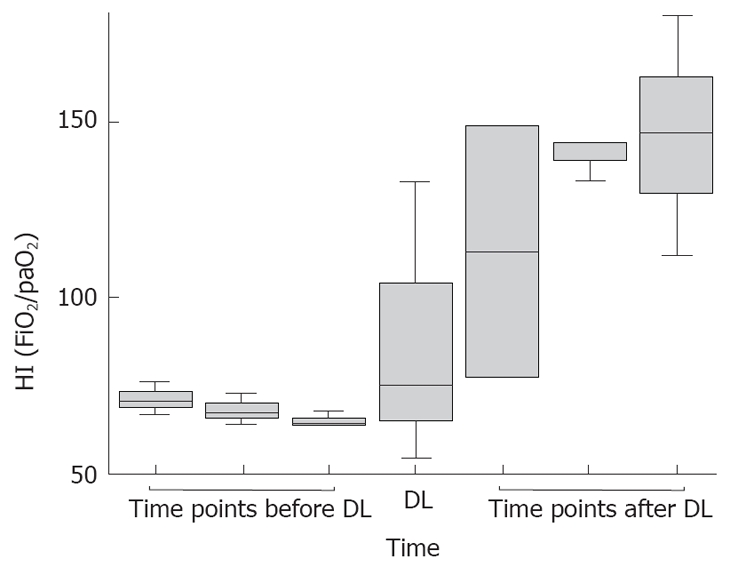

Figure 3.

Development of Horowitz-indices (HI). In the Box blots, the HI 3, 2 and 1 d before, at and 1, 2 and 3 d after DL of all 3 patients is shown. The line refers to the median, whereas the boxes refer to the interquartile ranges. The whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We present three cases of patients with SAP developing ACS leading to severe limitations of respiratory therapy. In each of these patients, decompression laparotomy caused immediate improvement in pulmonary function and led to definite survival in two cases.

Approximately 30%-40% of SAP patients develop ACS because of pancreatic-retroperitoneal inflammation, edema of peripancreatic tissue, fluid formation or abdominal distension, subsequently leading to intestinal ischemia with ileus and renal failure[5]. Besides, additional fluid resuscitation is known to further increase IAP. It was reported that ACS generally affects cardiac, pulmonary and renal function, and contributes to multi-organ dysfunction with a mortality rate ranging 10%-50% within two weeks[6,8-11]. The degree of IAP in patients with SAP seems to correlate with the degree of organ dysfunction, the severity of disease, the length of intensive care unit stay and mortality[6,8-11].

Pulmonary side effects mediated by IAH, such as atelectasis, edema, decreased oxygen transport and increased intrapulmonary shunt fraction, are caused by compression of pulmonary parenchyma. IAP is transmitted to the thorax through the elevated diaphragm and causes pulmonary parenchyma compression. The abdominal pressure on lung parenchyma is aggravated in mechanically ventilated patients due to high positive airway pressure, thereby leading to an elevated risk of alveolar barotraumas[12]. Furthermore, a study in ACS trauma patients demonstrated an increased rate of pulmonary infections[13].

Animal and human studies showed that abdominal decompression laparotomy can reverse the cardiopulmonary and abdominal effects of ACS[9,10]. In our patients, decompression laparotomy led to decreased IAP levels, improved Horowitz indices and increased lung compliance (Figure 3). Ventilation pressures could be reduced in order to re-achieve a lung protective ventilation regime. In addition, all three patients benefited from improving renal perfusion (rising urine volume and decreasing creatinine and urea levels), mesenterial perfusion (declining lactate levels) and cardiac output (less need for catecholamines). Moreover, patients with SAP may specifically profit from decompression laparotomy since elevated IAP influences pancreatic and intestinal perfusion and might therefore contribute to pancreatic necrosis[14].

Although decompression laparotomy can lead to recovery of patients with SAP from respiratory failure, its complications, such as massive intra-abdominal bleeding, need to be taken into account. Moreover, not only surgical complications but also persisting open abdomen is associated with risks and subsequent extensive abdominal wall reconstruction. New surgical concepts like subcutaneous anterior abdominal fasciotomy[15] may minimize complications and reach comparable clinical improvement in patients with SAP and ACS. Randomized studies are few so far, and the use of decompression laparotomy for ACS has been criticized by several authors since the mortality remains high in these patients[5,16].

Abdominal decompression laparotomy may help to overcome respiratory failure in patients with abdominal compartment syndrome and severe acute pancreatitis. Therefore, serial indirect measurement of IAP through an indwelling transurethral bladder catheter should be used routinely in critically ill patients with SAP in order to detect ACS. We hold that decompression laparotomy should be performed in patients with SAP and IAH/ACS with severe limitation of mechanical ventilation. However, prospective randomized studies are needed to further define the role of surgical decompression in SAP.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Capecomorin S Pitchumoni, Professor, Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine, New Brunswiuc NJ D8903, United States

S- Editor Zhong XY L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Yin DH

References

- 1.De Campos T, Deree J, Coimbra R. From acute pancreatitis to end-organ injury: mechanisms of acute lung injury. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2007;8:107–120. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner J, Feuerbach S, Uhl W, Buchler MW. Management of acute pancreatitis: from surgery to interventional intensive care. Gut. 2005;54:426–436. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheatham ML, Malbrain ML, Kirkpatrick A, Sugrue M, Parr M, De Waele J, Balogh Z, Leppaniemi A, Olvera C, Ivatury R, et al. Results from the International Conference of Experts on Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. II. Recommendations. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:951–962. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gecelter G, Fahoum B, Gardezi S, Schein M. Abdominal compartment syndrome in severe acute pancreatitis: an indication for a decompressing laparotomy? Dig Surg. 2002;19:402–404; discussion 404-405. doi: 10.1159/000065820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Waele JJ, Hesse UJ. Life saving abdominal decompression in a patient with severe acute pancreatitis. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105:96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keskinen P, Leppaniemi A, Pettila V, Piilonen A, Kemppainen E, Hynninen M. Intra-abdominal pressure in severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2007;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong K, Summerhays CF. Abdominal compartment syndrome: a new indication for operative intervention in severe acute pancreatitis. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:1479–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang WF, Ni YL, Cai L, Li T, Fang XL, Zhang YT. Intra-abdominal pressure monitoring in predicting outcome of patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:420–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang MC, Miller PR, D'Agostino R Jr, Meredith JW. Effects of abdominal decompression on cardiopulmonary function and visceral perfusion in patients with intra-abdominal hypertension. J Trauma. 1998;44:440–445. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obeid F, Saba A, Fath J, Guslits B, Chung R, Sorensen V, Buck J, Horst M. Increases in intra-abdominal pressure affect pulmonary compliance. Arch Surg. 1995;130:544–547; discussion 547-548. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430050094016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugerman HJ, Bloomfield GL, Saggi BW. Multisystem organ failure secondary to increased intraabdominal pressure. Infection. 1999;27:61–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02565176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quintel M, Pelosi P, Caironi P, Meinhardt JP, Luecke T, Herrmann P, Taccone P, Rylander C, Valenza F, Carlesso E, et al. An increase of abdominal pressure increases pulmonary edema in oleic acid-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:534–541. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1060OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aprahamian C, Wittmann DH, Bergstein JM, Quebbeman EJ. Temporary abdominal closure (TAC) for planned relaparotomy (etappenlavage) in trauma. J Trauma. 1990;30:719–723. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199006000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotzampassi K, Grosomanidis B, Dadoukis D, Eleftheriadis E. Retroperitoneal compartment pressure elevation impairs pancreatic tissue blood flow. Pancreas. 2007;35:169–172. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000281355.67633.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leppaniemi AK, Hienonen PA, Siren JE, Kuitunen AH, Lindstrom OK, Kemppainen EA. Treatment of abdominal compartment syndrome with subcutaneous anterior abdominal fasciotomy in severe acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2006;30:1922–1924. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Waele JJ, Hoste EA, Malbrain ML. Decompressive laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome--a critical analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R51. doi: 10.1186/cc4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]