Abstract

Non-weight-bearing, pre- and postsurgical immobilization, neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy are known to act on bone turnover, causing osteoporosis over short and long time periods. Treatment of fracture insurgence is very difficult because it really depends on being able to choose the right time (i.e., when immunodeficiency is less important). We report a case of spontaneous neck femur fracture during adjuvant chemotherapy in a young girl treated with resection and prosthesis reconstruction for distal femur osteosarcoma. Possible prevention and the correct approach and surgical timing are emphasized considering immunodeficiency following chemotherapy.

Keywords: Chemotherapy osteoporosis, Juvenile osteoporosis, Osteoporosis fracture children, Methotrexate complications

Introduction

Non-use osteoporosis is well known in the literature; it is caused by a decrease in osteoblastic activity arising from an absence of weight bearing and motion. Chemotherapy in patients who have undergone bone tumor surgery causes osteoblast inhibition and consequently a decrease in bone apposition and body mass density [1–6]. Methotrexate directly locks onto osteoblastic proliferation in the epiphyseal plate, inducing apoptosis and a drop off in type-II collagen synthesis; in spongy bone, it appears to act directly on osteoclast cell differentiation; osteoporotic fracture is a possible complication [7].

The other three drugs used in our therapeutic protocols, are doxorubicin, cisplatin and ifosfamide, and they can also diminish bone apposition; their effects on bone resistance become more evident with advanced age [8]. Osteoporotic fractures are common complications in patients who have undergone chemotherapy [9, 10].

Case report

A 14-year-old Caucasian girl showed up at our department for the onset of a tumefaction located in the posteromedial aspect of the distal right femur. Examination showed a mass seven centimeters in apparent size that was painful, hard, mobile on the overlying layers and fixed in the underlying layers.

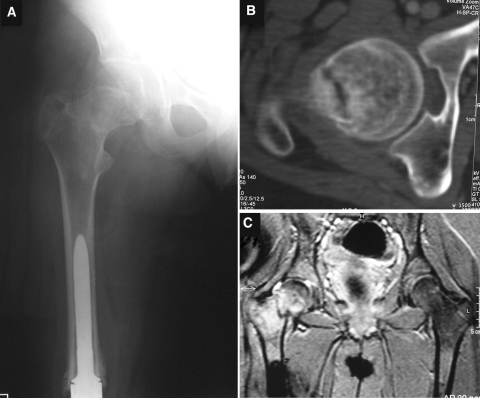

Distal femur X-rays indicated an osteolytic lesion with cortical erosion and minimal periosteal reaction (Codman’s triangle). Imaging was suggestive of a high-grade osseous sarcoma (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a–c Preoperative images showing a mass in the medial aspect of the distal femur. d Postoperative X-rays showing the prosthesis at the site

MRI (Fig. 1b) showed neoformation with various aspects that was more evident on STIR-weighted images and hypointense on T1-weighted images. It extended throughout the whole distal femur eroding medial cortex and periosteum without exceeding the epiphyseal plate; this condition was confirmed by TC (Fig. 1c). Bone scans revealed intense local uptake and no bone metastasis; this condition was also evident in total-body TC.

A needle biopsy was performed by medial access and following histopathology-documented osteosarcoma. The patient was placed in an oncology ward for neoadjuvant chemotherapy with methotrexate, cisplatin, adriamycin and ifosfamide (Italian Sarcoma Group Protocol) [11, 12].

The surgical operation was performed seven days after the last chemotherapy cycle. A tumor resection and reconstruction with global modular replacement system arthroplasty (GMRS, Stryker®) was performed (Fig. 1d). Postoperative days were normal, and when the wound had healed completely the patient was treated with adjuvant chemotherapy.

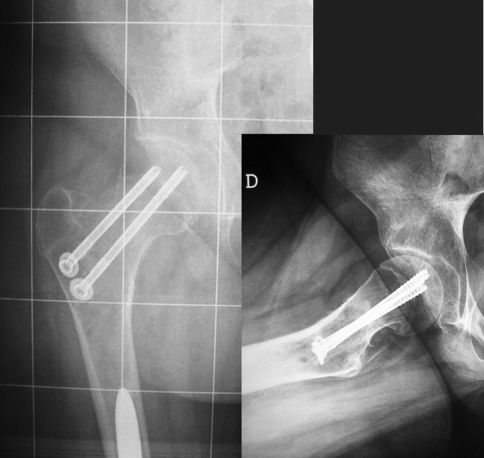

Seven months after the surgery, a nondisplaced asymptomatic neck fracture of the right femur was diagnosed by routine X-ray and CT scans (Fig. 2a, b). The patient related no trauma but suffered sudden pain after twisting her right leg. MRI with contrast clearly showed that it was not a metastasis, so biopsy was considered unhelpful (Fig. 2c) [13]. A percutaneous fixation with cannulated screws was performed in the period between the last chemotherapy and the next, when immunodeficiency was less important.

Fig. 2.

a X-rays showing a nondisplaced fracture; b CT scan showing correct fragment apposition; c T1-weighted MRI image showing no metastasis on the proximal right femur

Postoperative days were normal, and weight-bearing was not allowed for 40 days. X-rays taken 60 days after surgery showed the healing process (Fig. 3). The fracture had healed at one year of follow up (Fig. 4). The patient and her parents gave their consent to the publication of the clinical case.

Fig. 3.

Postoperative check showing that the fracture had been stabilized by cannulated screws

Fig. 4.

X-rays showing that the fracture had healed at one year of follow up

Discussion

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy caused a revolution in the treatment of musculoskeletal sarcoma, increasing the percentage of treatment success. The most popular treatment protocol is based on the administration of four chemotherapy drugs: methotrexate, cisplatin, adriamycin, and ifosfamide. Above all, methotrexate is known to be related to a drop in bone mass density, a decrease in osteoblastic activity, and a stimulation of osteoclast cell differentiation over the short term, as well as a decrease in peak adolescent bone mass and a facilitation of future osteoporosis over the long term [14–16]; moreover, methotrexate osteopathy, characterized by osteoporosis and joint pain, has been described [17].

Toxic effects of ifosfamide on bone were recently reported [18]. Pre- and postsurgery immobilization and a decline in normal activity are other important causes of worsening osteoporosis. Osteopenia was first described in long-term survivors of osteosarcoma in 1988, and remains evident many years after chemotherapy [19].

Although osteoporosis is well known in patients undergoing chemotherapy for osteosarcoma, there are no cases of spontaneous fracture in adolescents and preadolescents. In our case, the therapeutic issue was whether to perform a surgical operation or use conservative management. The fracture occurred about 20 days before, and in a healthy young girl this is a sufficient length of time for the fracture to heal. However, in these patients, chemotherapy retards the healing process, so this fracture was probably destined to evolve into a pseudarthrosis. The other problem was to choose the best time for the operation, because chemotherapy causes immunodeficiency, which can increase the risk of infections and wound closure problems. The patient had been administered high-dose ifosfamide, and growth factors were administered to decrease the risk of myelotoxicity, meaning that surgery was possible about one week after chemotherapy without the need to postdate the next cycle [20]. Prevention may be a valid approach for patients that have undergone chemotherapy. Bisphosphonates derive from the union of two phosphonic acids joined to one carbon atom; particular formulations are able to interfere with osteoclast precursor activation, preventing bone linkage and slowing bone resorption [21]. As it is already done for osteoporosis associated with other pathologies (like lymphoblastic leukemia) [22], their assumed use is rational, but new clinical trials are needed to evaluate a possible decrease in bone growth and retarded prosthesis integration.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Carmine Zoccali, Phone: +39-338-6355040, FAX: +39-06-52662778, Email: carminezoccali@libero.it.

Umberto Prencipe, Email: prencipe@ifo.it.

Virginia Ferraresi, Email: ferraresi@ifo.it.

Nicola Salducca, Email: salducca@ifo.it.

References

- 1.Aisenberg J, Hsieh K, Kalaitzoglou G, Whittam E, Heller G, Schneider R, Sklar C (1998) Bone mineral density in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 20:241–245 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Arikoski P, Komulainen J, Riikonen P, Voutilainen R, Knip M, Kroger H (1999) Alterations of bone turnover and impaired development of bone mineral density in newly diagnosed children with cancer: a 1-year prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:3174–3181 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Henderson RC, Madsen CD, Davis C, Gold SH (1996) Bone density in survivors of childhood malignancies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 18:367–371 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Henderson RC, Madsen CD, Davis C, Gold SH (1998) Longitudinal evaluation of bone mineral density in children receiving chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 20:322–326 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Kelly J, Damron T, Grant W, Anker C, Holdridge S, Shaw S, Horton J, Cherrick I, Spadaro J (2005) Cross-sectional study of bone mineral density in adult survivors of solid pediatric cancers. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 27:248–253 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Brosnan P, Delpassand A, Zietz H, Klein MJ, Jaffe N (1999) Osteopenia in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol 32:272–278 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ecklund K, Laor T, Goorin AM, Connolly LP, Jaramillo D (1997) Methotrexate osteopathy in patients with osteosarcoma. Radiology 202(2):543–547 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Virolainen P, Inoue N, Nagao M, Frassica FJ, Chao EY (2002) The effect of a doxorubicin, cisplatin and ifosfamide combination chemotherapy on bone turnover. Anticancer Res 22(4):1971–1975 [PubMed]

- 9.Neglia JP, Nesbit ME Jr (1993) Care and treatment of long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer 71(10 Suppl):3386–3391 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Pfeilschifter J, Diel IJ (2000) Osteoporosis due to cancer treatment: pathogenesis and management. J Clin Oncol 18(7):1570–1593 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ferrari S, Smeland S, Mercuri M, Bertoni F, Longhi A, Ruggieri P, Alvegard TA, Picci P, Capanna R, Bernini G, Müller C, Tienghi A, Wiebe T, Comandone A, Böhling T, Del Prever AB, Brosjö O, Bacci G, Saeter G, Italian, Scandinavian Sarcoma Groups (2005) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with high-dose ifosfamide, high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and doxorubicin for patients with localized osteosarcoma of the extremity: a joint study by the Italian and Scandinavian Sarcoma Groups. J Clin Oncol 23(34):8845–8852 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Bacci G, Ferrari S, Longhi A, Picci P, Mercuri M, Alvegard TA, Saeter G, Donati D, Manfrini M, Lari S, Briccoli A, Forni C, Italian Sarcoma Group/Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (2002) High dose ifosfamide in combination with high dose methotrexate, adriamycin and cisplatin in the neoadjuvant treatment of extremity osteosarcoma: preliminary results of an Italian Sarcoma Group/Scandinavian Sarcoma Group pilot study. J Chemother 14(2):198–206 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Campanacci M (1999) Bone and soft tissue tumors, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

- 14.Holzer G, Krepler P, Koschat MA, Grampp S, Dominkus M, Kotz R (2003) Bone mineral density in long-term survivors of highly malignant osteosarcoma. J Bone Jt Surg Br 85(2):231–237 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ripamonti C, Avella M, GNudi S, Figus E (1993) Effect of high and low doses of methotrexate (MTX) on bone mass in subjects treated for osteosarcoma of the limb. Minerva Med 84:131–134 [PubMed]

- 16.Xian CJ, Cool JC, Scherer MA, Macsai CE, Fan C, Covino M, Foster BK (2007) Cellular mechanisms for methotrexate chemotherapy-induced bone growth defects. Bone 41(5):842–850 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Rooney P (1996) Methotrexate osteopathy. J Rheumatol 23(12):2156–2159 [PubMed]

- 18.De Schepper J, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Louis O, Maurus R, Otten J (1994) Bone metabolism and mineralisation after cytotoxic chemotherapy including ifosfamide. Arch Dis Child 71:346–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Gnudi S, Butturini L, Ripamonti C, Avella M, Bacci G (1988) The effects of methotrexate (MTX) on bone: a densitometric study conducted on 59 patients with MTX administered at different doses. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 14:277–331 [PubMed]

- 20.Antman KH, Elias A, Ryan L (1990) Ifosfamide and mesna: response and toxicity at standard-and high-dose schedules. Semin Oncol 17(2 Suppl 4):68–73 [PubMed]

- 21.Fleisch H (1998) Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 19:80–100 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lethaby C, Wiernikowski J, Sala A, Naronha M, Webber C, Barr RD (2007) Bisphosphonate therapy for reduced bone mineral density during treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood and adolescence: a report of preliminary experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 29(9):613–616 [DOI] [PubMed]