Abstract

Members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and T-box gene families play several critical roles in the early embryonic development and tissue homeostasis. Although BMP proteins are the upstream regulators of T-box genes, few studies have investigated the molecular mechanisms between these two protein families. Here, we report that Tbx6 interacts directly with Smad6, an inhibitory Smad that antagonizes the BMP signal. This interaction is mediated through the Mad homology 2 (MH2) domain of Smad6 and residues 90–180 of Tbx6. We demonstrate that Smad6 facilitates the degradation of Tbx6 protein through recruitment of Smurf1, a ubiquitin E3 ligase. Consequently, Smad6 reduces Tbx6-mediated Myf-5 gene activation. Furthermore, specific knockdown of endogenous Smad6 and Smurf1 by small interfering RNA increases the protein levels of Tbx6 and enhance the expression of Tbx6 target genes. Collectively, these findings reveal that Smad6 serves as a critical mediator of BMP signal via a functional interaction with Tbx6, thus regulating the activation of Tbx6 downstream genes during cell differentiation.

Members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)2 family are multifunctional cytokines that play critical roles in embryogenesis and other biological processes, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and cell fate determination (1, 2). BMPs trigger cell responses mainly via the Smad pathway, which requires two types of receptor kinases and a family of signal transducers called R-Smads (Smad1, -5, and -8) (3). Upon phosphorylation, R-Smads form complexes with the common partner Smad4 (co-Smad) and then translocate into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes. The third subclass of Smads is composed of Smad6 and Smad7. Once induced by BMP signal, Smad6 functions as a potent antagonist in a negative feedback loop (4, 5).

The T-box genes encode a phylogenetically conserved family of transcription factors that share a common DNA-binding motif known as the T-box domain. T-domain proteins are essential for a variety of developmental events ranging from mesoderm specification to limb and heart development (6, 7). Mutations of T-box genes are implicated in human disorders such as DiGeorge and Holt-Oram syndromes (8). Brachyury (also known as T), the founding member of this gene family, was originally identified in short-tailed mice. Tbx6 (T-box 6) is expressed in the primitive streak, nascent mesoderm and later in the tailbud region of the developing mouse embryo, largely overlapping with the expression pattern of Brachyury (9). The defect in mouse Tbx6 leads to embryonic lethality with ectopic neural tube-like structures instead of posterior somites, indicating that Tbx6 is necessary for the specification of mesoderm precursor cells (10).

Accumulating evidence implies that the functions of BMPs and T-box proteins are closely related (11–14). During some stages of embryogenesis, both BMPs and T-box proteins participate in common developmental processes. For instance, Dorsocross, a Tbx6-related gene in Drosophila, exhibits an expression pattern similar to that of pMad (the phosphorylated form of the Mad protein) in the early blastoderm and the lateral ectoderm after germband elongation, implying a functional association between these two proteins (11). Several T-box genes are downstream targets of BMP signal. BMP-2 can promote Tbx2 and Tbx3 expression in chick, whereas Tbx2 expression is greatly reduced in homozygous Bmp-2 mouse mutants (12). In particular, BMP-4 induces ectopic Tbx6 expression in Xenopus animal cap explants (13), and BMP signal regulates zebrafish Tbx6 expression through a novel BMP-response element within the promoter (14). Beyond the upstream regulation of T-box gene expression by BMP signal, specific protein interactions with other factors in this signaling cascade are also suggestive of their intrinsic links. However, few reports describe interaction partners for T-domain proteins. Here, we have identified Smad6 as a novel Tbx6-interacting protein. We further demonstrate that Smad6 reduces Tbx6-mediated transcriptional activity by accelerating Tbx6 ubiquitination and degradation, thus regulating the expression of Tbx6 target genes during cell differentiation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

Full-length cDNAs encoding mouse Tbx6 and its serial deletion mutants were amplified by a PCR-based approach and verified by DNA sequencing. The sequences were cloned into pcDNA3 vectors (Invitrogen) with a hemagglutinin or Myc tag at the N terminus. Tbx6 and Smad6 were subcloned into PET-28b(+) (Novagen) and pGEX-4T-3 (Amersham Biosciences) vectors for expression in bacteria. The siRNAs for Tbx6, Smad6, Smurf1, and Smurf2 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. FLAG-tagged Smad1–7 constructs were kind gifts from Dr. Y. G. Chen (Tsinghua University, China). FLAG-tagged Smad6 deletion mutants were kindly provided by Dr. X. H. Feng (Baylor College of Medicine). Hemagglutinin-tagged Smurf1 and point mutant Smurf1C699A were generously provided by Dr. Joan Massagué (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center). The Myf-5 promoter-reporter (Myf-5-pGL3), 4×Tbx-TK and 4×mTbx-TK reporter constructs, and Xenopus Tbx6 and Brachyury expression plasmids with a 6×Myc tag at the N terminus were described in our previous papers (15, 16).

Cell Culture and DNA Transfection

HEK 293T and COS-7 cells, obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA), were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere. TT-D6 cells (a kind gift from Dr. M. Noda) were cultured in α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biochrom) at 33 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere. Transient transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

GST Pulldown Assay

Recombinant proteins expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) were induced with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 16 h at 22 °C. The cells were collected, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and mixture protein inhibitors), and sonicated. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) or GST-Smad6 fusion protein was bound to glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma) and incubated for 3 h with total lysates from His6-Tbx6-expressing E. coli cells. The beads were washed three times with GST lysis buffer. The proteins were eluted with 2× SDS loading buffer and analyzed by Western blotting analysis using anti-GST and anti-His monoclonal antibodies (Sigma).

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with various expression plasmids as indicated and incubated for 24 h before analysis. For the ubiquitination assay, cells were treated with MG132 (Sigma) at a final concentration of 10 μm for 4 h prior to harvesting. Cell lysate preparation and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously (17, 18). Bound proteins were then eluted and subjected to Western blotting analysis using anti-ubiquitin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to detect the Tbx6-ubiquitin conjugation.

To detect the potential interaction between endogenous Smad6 and Tbx6, 1 × 107 TT-D6 cells were lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, and a mixture protein inhibitors (Bio Basics). Immunoprecipitation was carried out using anti-Smad6 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or normal rabbit IgG. The proteins were then eluted and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Tbx6 polyclonal antibody (Aviva Systems Biology). Other primary antibodies described in this article include anti-Myf-5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-p-Smad1/5/8 (Cell Signaling), anti-Smurf1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Smurf2 (Abcam), and anti-β-actin (Sigma) antibodies.

Luciferase Assay

To evaluate the transcriptional activity of Tbx6, we used the reporter construct Myf-5-pGL3, which contains a 5.4-kb upstream region of the Myf-5 promoter driving luciferase expression (15). The 4×Tbx-TK reporter contains four tandem repeats of T-box binding site upstream of the thymidine kinase (TK) basal promoter. The 4×mTbx-TK reporter with four mutant T-box binding sites was used as a negative control (16). TT-D6 cells (5 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate) were transiently transfected with plasmids as indicated in Figs. 3–5. Empty vector pCS2+ was used to keep the total amount of transfected DNA constant (500 ng/well) in each well in all experiments. Luciferase activity in the samples was measured after 24 h of transfection using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity in each sample. All assays were performed in triplicate, and the data are shown as the mean ± S.E. of at least two independent experiments.

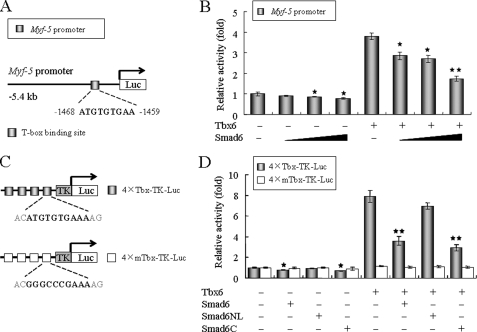

FIGURE 3.

Smad6 inhibits Tbx6-dependent transcriptional activity. A, schematic diagram depicts the Myf-5 promoter-reporter used in the luciferase assay. The upstream region of the Myf-5 promoter contains a conserved T-box binding site that is activated by Tbx6 (16). B, Smad6 significantly represses Tbx6-mediated Myf-5 gene activation in a dose-dependent manner. The Myf-5 promoter-reporter (50 ng) was co-transfected with Tbx6 (100 ng) and increasing doses of Smad6 construct (0, 100, 200, and 400 ng; represented by the black triangles) into TT-D6 cells. pRL-SV40 plasmid (2.5 ng) expressing Renilla luciferase was co-transfected in each well as an internal control. C, schematic representations of 4×Tbx-TK and 4×mTbx-TK reporter constructs. D, similar studies were carried out using the 4×Tbx-TK or 4×mTbx-TK reporter construct. The Smad6 deletion mutant Smad6NL, which lacks the Tbx6-binding domain, failed to reduce Tbx6-mediated transcriptional activity, indicating that Smad6 reduces the transcriptional activity of Tbx6 via its C terminus. Data for all panels are reported as relative luciferase activity standardized to Renilla luciferase protein. All assays were performed in triplicate, and the data are shown as the mean ± S.E. of at least two independent experiments. Asterisks denote significant differences (p < 0.05) within the experiments using Student's t test.

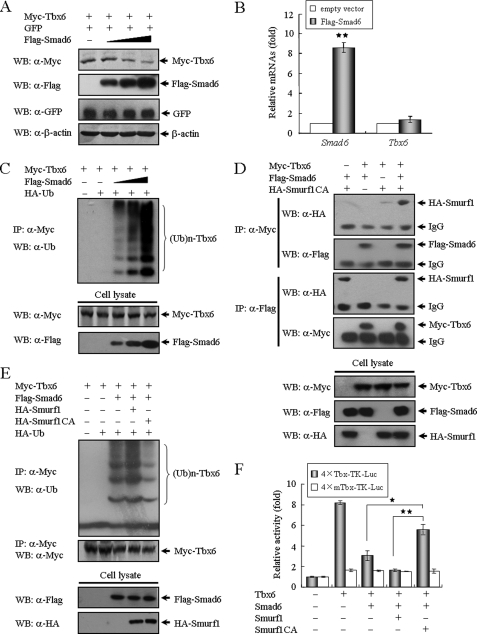

FIGURE 4.

Smad6 mediates Tbx6 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. A, Smad6 induces Tbx6 degradation in a dose-dependent manner. Tbx6 expression construct (100 ng) was co-transfected with increasing amounts of Smad6 (0, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 μg/well in a 12-well plate; represented by the black triangle) expression plasmid into HEK 293T cells. In each transfection, an equal amount of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression plasmid (50 ng) was included as an internal control. The protein levels of Tbx6 and Smad6 in whole cell lysates were detected by Western blotting (WB). β-Actin was used as a loading control. B, overexpression of Smad6 has no obvious effect on the mRNA level of Tbx6. TT-D6 cells transfected with control or Smad6 expression plasmids were subjected to RT-PCR analysis for related gene expression. The relative value for each target gene was normalized to the average intensity of the endogenous control gene, GAPDH. **, p < 0.01. C, Smad6 mediates Tbx6 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in a dose-dependent manner. 293T cells were transfected with expression constructs in the indicated combinations. After 24 h of transfection, cells were treated with 10 μm MG132 for 4 h before harvesting. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using anti-Myc antibody and followed by Western blotting using anti-ubiquitin antibody. D, Tbx6 forms a ternary complex with Smad6 and Smurf1. Protein extracts from 293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc or anti-FLAG antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. E, Smurf1 promotes Smad6-mediated Tbx6 ubiquitination. Tbx6 ubiquitination was assessed as described above. HA, hemagglutinin; Ub, ubiquitin. F, Smurf1 cooperates with Smad6 to dramatically reduce Tbx6-dependent transcriptional activity. TT-D6 cells were co-transfected with 4×Tbx-TK or 4×mTbx-TK reporter and additional expression constructs including Tbx6, Smad6, Smurf1, and its inactive mutant, in different combinations as indicated. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 using Student's t test.

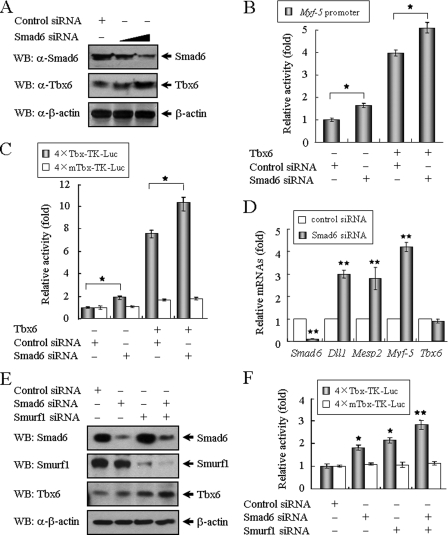

FIGURE 5.

Knockdown of Smad6 and Smurf1 enhance Tbx6-mediated transcriptional activity. A, knockdown of Smad6 increases the levels of endogenous Tbx6 protein. TT-D6 cells were transfected with control or Smad6 siRNA and then assayed by Western blotting (WB) using anti-Smad6 and anti-Tbx6 antibodies. B, siRNA against Smad6 partially relieved the Smad6-mediated suppression of Myf-5 transcription. Control or Smad6 siRNA was co-transfected with Myf-5 promoter-reporter in the absence or presence of Tbx6 expression plasmid. An asterisk denotes significant differences (p < 0.05) within the experiments using Student's t test. C, similar studies were carried out using the 4×Tbx-TK or 4×mTbx-TK reporter constructs. An asterisk denotes significant differences (p < 0.05) within the experiments using Student's t test. D, knockdown of Smad6 enhances the expression of Tbx6 downstream genes. TT-D6 cells transfected with control or Smad6 siRNA were subjected to RT-PCR analysis for related gene expression. The relative value for each target gene was normalized to the average intensity of an endogenous control, GAPDH. **, p < 0.05. E, Smad6 and Smurf1 cooperate to regulate Tbx6 protein levels. TT-D6 cells were transfected with Smad6 siRNA and/or Smurf1 siRNA. After 48 h of culture, cell lysates were assayed by Western blotting using anti-Smad6, anti-Smurf1, and anti-Tbx6 antibodies. F, inhibition of Smad6 and Smurf1 expression enhance the transcriptional activity of Tbx6. 4×Tbx-TK reporter construct was co-transfected with Smad6 and/or Smurf1 siRNA. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 using Student's t test.

Histochemical Assessment for Osteoblastic Differentiation

TT-D6 cells were seeded into 24-well plates and cultured with or without 500 ng/ml rhBMP-2 (R&D Systems) for 72 h. The activity of alkaline phosphatase was evaluated using the alkaline phosphatase substrate kit III (Vector Laboratories) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. For the mineralization assay, the cell layers were fixed with 10% formaldehyde solution for 15 min and stained with 1% Alizarin Red S (Sigma) for 5 min. Cells were then washed with distilled water and air-dried. The stained calcified nodules, which appeared bright red in color, were identified by light microscopy.

Immunofluorescence Staining

As described previously (17), TT-D6 cells grown on coverslips were fixed and then stained with anti-Smad6 (1:100) and anti-Tbx6 polyclonal antibodies (1:1000) followed by Cy2-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and Cy3-conjugated anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription were performed as described previously (18). All assays were performed in triplicate for each sample. The intensity of each amplified band was measured and normalized to its corresponding GAPDH content. The optimal primers for PCR are as follows: ALP (fwd, 5′-TGCCTACTTGTGTGGCGTGAA-3′; rev, 5′-TCACCCGAGTGGTAGTCACAATG-3′); Dll1 (fwd, 5′-ACTCCTTCAGCCTGCCTGA-3′, rev, 5′-TATCGGATGCACTCATCGC-3′); GAPDH (fwd, 5′-CGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTAT-3′, rev, 5′-AGCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGAC-3′); Myf-5 (fwd, 5′-GGATGAGTTTGGGGACCAGTTTG-3′, rev, 5′-GTCCCGGCAGGCTGTAATAGTTC-3′); MyoD (fwd, 5′-AGGCTCTGCTGCGCGACC-3′, rev, 5′-TGCAGTCGATCTCTCAAAGCACC-3′); Mesp2 (fwd, 5′-TGGCTGTCCTGAACTTTGG-3′, rev, 5′-GGAGTATGGAACGACCCTCT-3′); osteocalcin (fwd, 5′-CCAAGCAGGAGGGCAATA-3′, rev, 5′-AGGGCAGCACAGGTCCTAA-3′); Runx2 (fwd, 5′-GGCAGCACGCTATTAAATCCAAA-3′, rev, 5′-TGACTGCCCCCACCCTCTTAG-3′); Smad6 (fwd, 5′-CCACTGGATCTGTCCGATTC-3′, rev, 5′-AAGTCGAACACCTTGATGGAG-3′); and Tbx6 (fwd, 5′-TTCCCTGCTTGCCGAGTATCAG-3′, rev, 5′-GGCATCCCGCTCCCTCTTACAG-3′).

RESULTS

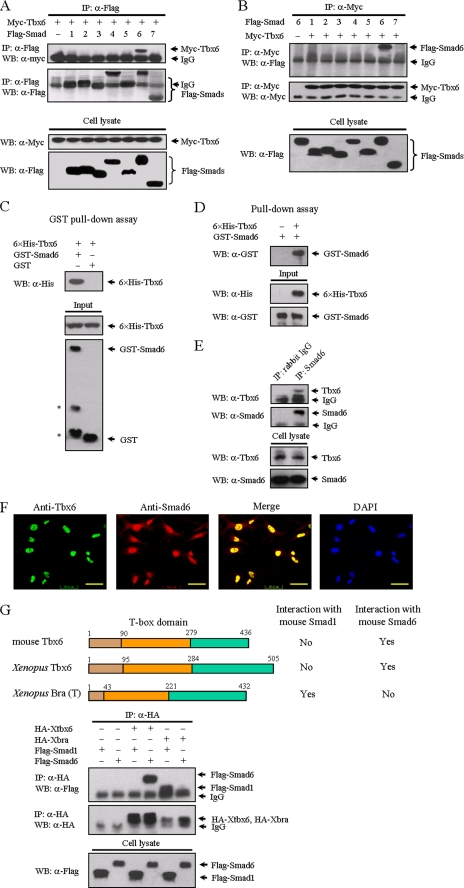

Tbx6 Interacts with Smad6

As a homologue of Brachyury, Tbx6 shares a high degree of sequence similarity. The expression pattern of Tbx6 and Brachyury mostly overlaps during early embryo development (9), implying a functional redundancy between these two proteins. Given that Xenopus Brachyury is reported to interact with Smad1 (19), we wondered whether Tbx6 protein might also interact with Smad1 or other Smad molecules. To address this possibility, we co-transfected Myc-tagged Tbx6 with FLAG-tagged Smad expression constructs into HEK 293T cells. The potential interaction between Tbx6 and Smad proteins was analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody followed by Western blotting using anti-Myc antibody. Interestingly, we found that, instead of interacting with Smad1, Tbx6 interacted with Smad6 but not other Smads (Fig. 1A). Reciprocal immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc was subsequently performed to confirm the specific interaction between Tbx6 and Smad6 (Fig. 1B). To further explore whether the association between these two proteins is direct, we carried out an in vitro GST pulldown assay using bacterially expressed GST-Smad6 and His6-Tbx6 fusion proteins. GST-Smad6 fusion protein, but not GST alone, was able to pull down His6-Tbx6, indicating that Tbx6 directly interacts with Smad6 (Fig. 1C). A reciprocal pulldown assay was applied to confirm the direct binding of Tbx6 and Smad6 in vitro (Fig. 1D). We then evaluated the ability of endogenous Tbx6 to associate with Smad6 in vivo. Because Tbx6 and Smad6 are both expressed endogenously in TT-D6 mesenchymal stem cells, we used this cell model for the following analyses. Total extracts from TT-D6 cells were incubated with beads conjugated to anti-Smad6 polyclonal antibody. As shown in Fig. 1E, Tbx6 was readily detected in the immunoprecipitated complex of Smad6, demonstrating that Tbx6 indeed interacts with Smad6 in vivo. Next, we focused on the subcellular localization of Tbx6 and Smad6 proteins. Tbx6 was detected in the nucleus, and Smad6 was distributed predominantly in the nucleus of TT-D6 cells (Fig. 1F). We also found that the co-localization of Tbx6 and Smad6 in the nucleus was not affected by BMP-2 (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Tbx6 interacts with Smad6. A, identification of Smad6 as a novel Tbx6-interacting protein. FLAG-tagged Smads 1–7 were individually co-transfected with Myc-tagged Tbx6 into HEK 293T cells as indicated. After transfection for 24 h, cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody, and analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with anti-Myc antibody (top panels). Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted directly with anti-Myc or anti-FLAG antibodies to demonstrate the expression of Myc-Tbx6 and FLAG-Smads, respectively (bottom panels). B, reciprocal immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc was carried out. Only Smad6 was co-precipitated with Tbx6. C, Tbx6 directly binds to Smad6 in vitro. Bacterially expressed GST-Smad6 fusion protein was purified using glutathione-agarose beads and incubated with His6-Tbx6 fusion protein. Associated His6-Tbx6 protein was readily detected by immunoblotting (top panel). The asterisks denote degraded bands of GST-Smad6 fusion protein (bottom panel). An equimolar amount of GST was used as a negative control. D, purified His6-Tbx6 fusion protein was incubated with GST-Smad6 and precipitated with anti-His antibody. Associated GST-Smad6 protein was detected by Western blot. E, interaction between endogenous Tbx6 and Smad6 in TT-D6 cells. TT-D6 cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Smad6 polyclonal antibody. Normal rabbit IgG was used as a negative control. The immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Tbx6 antibody. F, Tbx6 is co-localized with Smad6 in the nucleus. TT-D6 cells were fixed and stained with the indicated antibodies to determine the localization of Tbx6 (green) and Smad6 (red). Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. The bar represents 50 μm for each section. G, T-box proteins have distinct affinities for different Smad proteins. Top, schematic diagrams depict Tbx6 homologues in mouse and Xenopus. Their interactions with Smad1 or Smad6 from co-immunoprecipitation experiments are shown in the bottom panels. HA, hemagglutinin.

Subsequently, we investigated whether Tbx6 homologues also share the ability to associate with Smad6. We found that both mouse and Xenopus Tbx6 showed similar affinities for mouse Smad6, whereas Xenopus Brachyury, the canonical member of the T-box gene family, does not interact with mouse Smad6 (Fig. 1G). Taking into account the recent finding that Xenopus Brachyury specifically interacts with Smad1 (19), our data suggest that T-box proteins have distinct affinities for different Smad proteins.

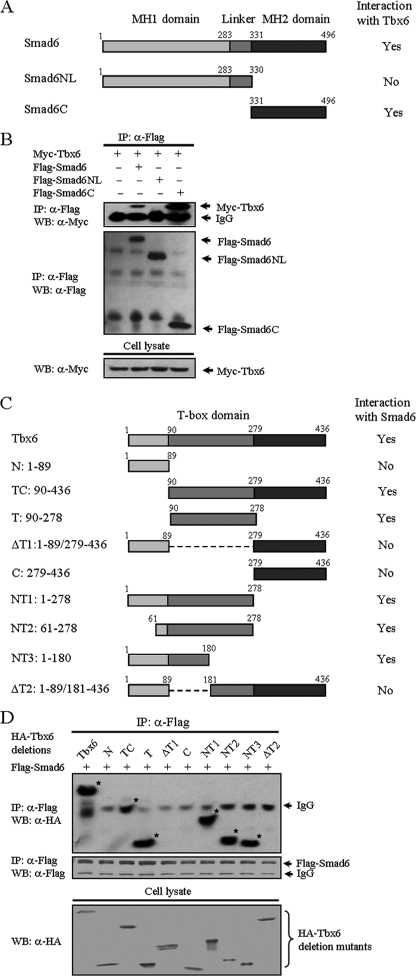

Determination of Mutual Interaction Regions in Smad6 and Tbx6

Smad proteins contain highly conserved N- and C-terminal regions termed Mad homology 1 (MH1) and Mad homology 2 (MH2) domains, respectively. The MH1 and MH2 domains are linked by a region of variable length and sequence. Smad6 has a conserved MH2 domain, whereas its N-terminal region is divergent from that of other Smads (Fig. 2A) (20). To identify the region of Smad6 involved in the association with Tbx6, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments using truncated mutants of Smad6. Compared with full-length Smad6, Smad6C protein (MH2 domain, residues 331–496) exhibited a stronger interaction with Tbx6. In contrast, deletion of the C-terminal domain (MH1 domain with the linker region referred to as Smad6NL, residues 1–330) completely abolished its ability to form a complex with Tbx6 (Fig. 2B), indicating that the MH2 domain of Smad6 mediates its interaction with Tbx6.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of domains for mutual interaction between Smad6 and Tbx6. A, schematic diagram of Smad6 and its deletion mutants. Functional domains of Smad6 are characterized above the schematic diagram. The interaction with Tbx6 from co-immunoprecipitation experiments is summarized on the right. B, mapping of the domain in Smad6 for interaction with Tbx6. HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with Myc-tagged Tbx6 and FLAG-tagged Smad6 deletion mutants. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody and then immunoblotted (WB, Western blot) with anti-Myc (top panel). The total level of Tbx6 protein expressed in whole cell lysates is also shown (bottom panel). The MH2 domain of Smad6 mediates its interaction with Tbx6. C, schematic representation of wild-type and deletion mutants of Tbx6. The T-box domain of Tbx6 protein (residues 90–279) is illustrated above the schematic diagram, and relative positions of the remaining fragment(s) in each deletion mutant are numbered on the left. The interaction with Smad6 is summarized on the right. D, identification of Smad6 binding sites on Tbx6. The region of residues 90–180 in Tbx6 contributes to its interaction with Smad6. *, bands consistent with protein-protein interaction. HA, hemagglutinin.

To delineate the interaction interface of Tbx6, we then constructed a series of Tbx6 deletion mutants (Fig. 2C). The rationale for designing these mutants was based on an existing understanding of important domains within Tbx6. Like the full-length Tbx6, deletion mutants T, TC, NT1, NT2, and NT3 retained their binding affinities for Smad6. However, Tbx6 deletion mutants N, ΔT1, C, and ΔT2 failed to bind to Smad6 (Fig. 2D). These results demonstrate that the region encompassing residues 90–180 in Tbx6 is responsible for its specific interaction with Smad6.

Smad6 Inhibits the Transcriptional Activity of Tbx6

To date, several downstream target genes of Tbx6 have been successfully identified. Myf-5, a myogenic regulatory factor, is one of these target genes. The skeletal muscle was conspicuously absent in teratomas derived from mouse Tbx6-null tailbud cells, implying a potential requirement for Tbx6 in myogenic specification or differentiation (21). Previously, we cloned a 5.4-kb fragment of the 5′-flanking sequence of the Myf-5 promoter (15) and identified a conserved T-box binding site in this fragment that mediated the activation of Myf-5 expression (16). To ascertain the functional significance of Tbx6/Smad6 complex formation, we first tested whether Smad6 could modulate Tbx6-mediated transcriptional activation using the Myf-5 promoter-reporter (Fig. 3A). As expected, overexpression of Tbx6 increased Myf-5 luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. S1A), whereas co-transfection with increasing amounts of Smad6 constructs resulted in a dramatic repression of Tbx6-induced Myf-5 transcriptional activity (p < 0.01; Fig. 3B).

The Myf-5 promoter contains a host of regulatory elements, including a T-box binding site, two Smad binding elements, and an interferon regulatory factor-like binding element (15, 16, 22). To verify that the repression of Myf-5 transcription by Smad6 was indeed mediated through the T-box binding site in the Myf-5 promoter, we used a 4×Tbx-TK reporter that contains four tandem repeats of the T-box binding site inserted upstream of the TK basal promoter (Fig. 3C) (16). As expected, overexpression of Tbx6 increased the 4×Tbx-TK reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. S1B). When Tbx6 and Smad6 were both expressed, a dramatic decrease of the reporter activity was observed (supplemental Fig. S1C). However, the Smad6 deletion mutant Smad6NL, which lacks the Tbx6-interacting domain, failed to reduce Tbx6-mediated transcriptional activity (Fig. 3D). Similar experiments were repeated in mouse C2C12 myoblast cells with essentially the same results (data not shown), indicating that Smad6 inhibits the transcriptional activity of Tbx6 through its interaction with Tbx6.

Smad6 Mediates Tbx6 Degradation

The above observations prompted us to further assess the protein levels of Tbx6 in Smad6-overexpressing cells. Tbx6 was co-transfected with different amounts of the Smad6 expression construct into HEK 293T cells, a cell line that has been used extensively in protein degradation studies of Smad2 and BMP receptors (23). It is noteworthy that Tbx6 protein was down-regulated by Smad6 in a dose-dependent manner (∼60% decrease) (Fig. 4A). Overexpression of Smad6 did not have an obvious effect on the transcriptional level of Tbx6 (Fig. 4B), and we thus speculated that it might be the result of Tbx6 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. To test our hypothesis, we examined the ubiquitination of Tbx6 after co-expression of Smad6. We found that Smad6 could induce Tbx6 polyubiquitination in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C). Moreover, when cells were treated with proteasome inhibitor (MG132), the interaction of Tbx6 with Smad6 was enhanced (supplemental Fig. S2A).

It is reported that Smurf1 can be recruited by Smad6 to BMP receptors to trigger the degradation of these receptors (24). Therefore, we checked whether Smad6 could also recruit Smurf1 to facilitate Tbx6 ubiquitination. First we examined the involvement of Smurf1 in the Tbx6-Smad6 interaction. Because Smurf1 is a ubiquitin E3 ligase, the catalytically inactive mutant Smurf1C699A was utilized to avoid protein degradation in the following assays. As shown in Fig. 4D, Tbx6 cannot directly interact with Smurf1 protein alone. When Smad6 was co-transfected with Tbx6 and Smurf1, both Smad6 and Smurf1 were present in the Tbx6-immunoprecipitated complex. Similarly, immunoprecipitation of Smad6 also led to detection of Smurf1 and Tbx6 in the same complexes. These data together indicate that Tbx6 forms a ternary complex with Smad6 and Smurf1. Because Tbx6 protein levels were significantly reduced in the presence of exogenous Smad6 and Smurf1 (supplemental Fig. S2B), we then explored the role of Smurf1 in regulating Smad6-mediated ubiquitination of Tbx6. As shown in Fig. 4E, Smad6 induced Tbx6 ubiquitination, presumably because of the basal expression of Smurf1. Wild-type Smurf1 elicited a significant increase in Smad6-induced Tbx6 ubiquitination, and the catalytically inactive mutant of Smurf1 largely blocked the ubiquitination of Tbx6, suggesting the requirement of Smurf1 in Smad6-mediated Tbx6 ubiquitination. Subsequently, we tested the effect of Smurf1 on Tbx6-induced transcriptional activity. As expected, Smad6 on its own showed only a partial inhibitory effect on Tbx6 activity, whereas Smad6 in cooperation with Smurf1 dramatically suppressed the transcriptional activity of Tbx6 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4F). Collectively, these data indicate that Smad6 reduces Tbx6-induced transcriptional activity through functional interaction with Tbx6 and mediates Tbx6 protein degradation through the recruitment of Smurf1 E3 ligase.

Knockdown of Smad6 and Smurf1 Enhances Tbx6-mediated Transcriptional Activity

To further investigate the role of endogenous Smad6 in the regulation of Tbx6 protein stability and Tbx6-dependent gene expression, we applied RNA interference techniques to TT-D6 cells, a cell line that endogenously expresses both Tbx6 and Smad6. The siRNA against Smad6 was highly effective in blocking endogenous Smad6 expression (∼75% suppression), whereas the endogenous levels of Tbx6 protein were increased by 2.5-fold (Fig. 5A). We tested the effects of Smad6 siRNA on Tbx6-mediated transcriptional activity. As shown in Fig. 5B, knockdown of endogenous Smad6 elevated the basal activity of the Myf-5 promoter. Compared with control cells, Myf-5 promoter activity was enhanced in Smad6 siRNA-treated cells in a manner that correlated highly with the percentage of loss of Smad6. Similar results were obtained using the 4×Tbx-TK reporter (Fig. 5C), showing that knockdown of Smad6 enhances Tbx6-induced transcriptional activity.

We then examined whether the loss of Smad6 impairs the endogenous expression of Tbx6 downstream genes in TT-D6 cells. In addition to Myf-5, Dll1 (Delta-like 1) and Mesp2 (mesoderm posterior 2) are also downstream targets of Tbx6 (25, 26). Application of Tbx6 siRNA markedly decreased the mRNA expression of Dll1, Mesp2, and Myf-5, supporting the idea that Tbx6 is required for the expression of these mesoderm markers (supplemental Fig. S3). Alternatively, knockdown of endogenous Smad6 resulted in significant augmentation of Dll1, Mesp2, and Myf-5 mRNAs (2.8–4.2-fold increases) (Fig. 5D). Moreover, Smad6 suppression had subtle effects on Tbx6 mRNA transcription, providing new evidence that Tbx6 is regulated by an interaction with Smad6 at the level of post-translational modification rather than transcriptional regulation.

To further determine the role of Smad6 and Smurf1 in the regulation of Tbx6 protein stability, we transfected TT-D6 cells with Smad6 and Smurf1 siRNAs. As shown in Fig. 5E, knockdown of endogenous Smad6 and Smurf1 increase Tbx6 protein levels. Similarly, inhibition of Smad6 and Smurf1 expression enhanced the transcriptional activity of Tbx6 (Fig. 5F). Unlike Smurf1, Smurf2 had no obvious effect on Tbx6 protein expression and transcriptional activity (supplemental Fig. S4). These results demonstrate that Smad6 and Smurf1 cooperate to regulate Tbx6 protein levels in TT-D6 cells.

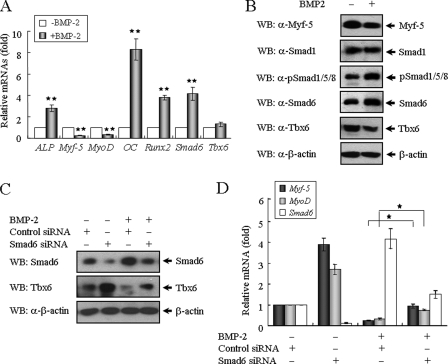

Smad6 Is Required for BMP2-mediated Inhibition of Myogenic Genes

Because BMP signal induces a switch in the differentiation of myogenic cells to the osteogenic lineage (27, 28), we examined the effects of BMP-2 on the osteoblastic differentiation of TT-D6 cells, a pluripotent mesenchymal stem cell line with multiple differentiation capabilities (29). Compared with the control culture, BMP-2 successfully induced the differentiation of TT-D6 cells into osteoblast phenotypes, resulting in a prominent increase of alkaline phosphatase activity, a typical index of osteoblastic differentiation (supplemental Fig. S5A). BMP-2 also promoted calcified nodule formation, as observed following Alizarin Red staining (supplemental Fig. S5B). BMP-2 stimulation increased the expression of osteoblastic marker genes such as ALP (alkaline phosphatase), osteocalcin (OC), and Runx2 (3–8-fold increases). At the same time, BMP-2 treatment reciprocally blocked the expression of Myf-5 (∼75% decrease) and MyoD (∼68% decrease), two master control genes that are critical for myogenic differentiation during early embryogenesis (Fig. 6A). When BMP-2 induced the differentiation of TT-D6 mesenchymal stem cells into the osteogenic lineage, the endogenous levels of Tbx6 and Myf-5 proteins were reduced (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

BMP-induced Smad6 expression is required for the inhibition of myogenic genes. A, TT-D6 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 500 ng/ml rhBMP-2 for 72 h. RT-PCR was performed to detect the effects of BMP-2 on gene expression levels related to osteoblast and myoblast markers in the TT-D6 cells. The quantitative ratios are shown as relative optical densities that are normalized to GAPDH expression. B, protein extracts from TT-D6 cells pretreated with or without BMP-2 were immunoblotted (WB, Western blot) with antibodies against the indicated targets, including β-actin as a loading control. C, Smad6 is required for the BMP-induced degradation of Tbx6 protein during osteoblastic differentiation. TT-D6 cells were transfected with control or Smad6 siRNA and treated with or without BMP-2 for 48 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted using anti-Smad6 and anti-Tbx6 antibodies. D, knockdown of endogenous Smad6 partially relieves the inhibitory effect of BMP signal on the expression of myogenic genes. Data are represented as means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; and **, p < 0.01 versus control.

Smad6 is transiently induced by BMP signal in a negative feedback mechanism (30, 31). Because Tbx6 associates with Smad6 in vivo (Fig. 1E), we hypothesized that Smad6 functions as a mediator of the BMP-induced degradation of Tbx6 protein during osteoblastic differentiation. TT-D6 cells were transfected with control or Smad6 siRNA and treated with or without BMP-2 for 48 h. We confirmed that both the mRNA and protein levels of Smad6 were enhanced after BMP-2 treatment (Fig. 6, A and B). In Smad6-knockdown cells, the Tbx6 protein levels were apparently not affected by BMP-2 treatment (Fig. 6C). Likewise, BMP failed to inhibit the expression of Myf-5 and MyoD when the expression of Smad6 was knock downed (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that BMP-induced Smad6 expression is required for both Tbx6 protein degradation and the inhibition of myogenic gene expression during cell differentiation. In conclusion, our data collectively show that Smad6 interacts with Tbx6 and acts as a negative regulator of Tbx6-mediated transcriptional activity by facilitating Tbx6 protein degradation.

DISCUSSION

BMPs are known as multifunctional regulators of vertebrate development (1, 2). Although the BMP/Smad signaling cascade is well characterized, it remains largely unknown how BMPs exert such diverse functions. The answer lies in the cross-talk between BMPs and other signaling pathways, as well as in the distinct transcription factors that are recruited by BMP signal. Our current results add to the short list of Smad6-interacting transcriptional factors and disclose a novel cross-talk between BMP signal and T-box proteins. Much evidence suggests that the MH2 domain of Smad6 is an effector domain, whereas the N-terminal region inhibits the biological activities of the MH2 domain through the interaction between these two distal sites (32–34). Our data in Fig. 2 indicate that the interaction of Tbx6 with the C terminus of Smad6 is much stronger than that with full-length Smad6, suggesting that the N terminus of Smad6 can negatively regulate the interaction between these two proteins. Likewise, an intact C-terminal domain in Smad7 is necessary and sufficient for association with TGF-β family receptors. Recent studies have shown that an intact C terminus of Smad7 is required for interaction with STRAP (serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein), a protein that stabilizes the interaction of Smad7 with the intracellular domain of TGF-β receptors and thus potentiates its inhibitory effects (35, 36). These data together support the idea that the C-terminal domain of inhibitory Smads is primarily responsible for protein interactions and biological activities.

The present study also provides novel evidence for the functional association between Smad6 and Tbx6. The unique role of Tbx6 as a transcriptional activator in the specification of mesoderm precursor cells is gradually becoming clear based on studies of vertebrate embryo development (10, 37, 38). Our finding that Tbx6 interacts with an inhibitory Smad may reflect an important instance of cross-talk between BMP signal and key developmental determinants such as T-box proteins. Furthermore, our results elucidate a physiological role for the Tbx6-Smad6 interaction in cell differentiation. Mesenchymal cells differentiate into distinct cell types such as adipocytes, osteoblasts, and myoblasts. Commitment to a specific lineage depends on mutually exclusive factors. Thus, external signals that induce a particular cell lineage must repress other differentiation potentials. Abundant reports have shown that BMP-2 inhibits the expression of myogenic genes during osteoblastic differentiation (27, 28) and that high concentrations of BMP-4 completely block the expression of myotomal markers, including Myf-5 in chick embryos (39). However, the actual mechanism has not been fully defined. Smad6 is a downstream target gene of BMP signal (30, 31). Therefore, it can be presumed that the BMP signal induces the expression of Smad6, which subsequently interacts with Tbx6 and accelerates Smad6-mediated Tbx6 protein degradation through the recruitment of Smurf1 E3 ligase, thus leading to the inhibition of myogenic genes during osteoblastic differentiation. In fact, when TT-D6 mesenchymal stem cells were induced to differentiate into osteoblasts by BMP-2 treatment, the levels of Tbx6 protein together with the expression of Myf-5 and MyoD were reduced to an extent consistent with the increase in Smad6 expression (Fig. 6). Based on our hypothesis, BMP-induced Smad6 expression is more than just a negative feedback loop of BMP signal. Increased BMP-dependent Smad6 expression may also lead to important modulation of Tbx6 protein stability and Tbx6-induced gene expression. Taking into account the eventual development of paraxial mesoderm into bones (sclerotome), muscles (myotome), and dermis (dermatome), we thus have highlighted the biological function of the physiological interaction between Tbx6 and Smad6. Overall, this study provides new insight into the potential mechanisms involved in the regulation of mesoderm cell fate determination and cell differentiation.

In this study, we have uncovered a novel aspect of T-box protein modification. Protein post-translational modification by ubiquitination is the primary mechanism that modulates the activity of specific proteins and mediates the selective degradation of master regulatory proteins by the proteasome. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway functions in numerous cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and pathogenesis (40, 41). However, the role of this pathway in the regulation of T-box proteins remains unclear. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that T-box proteins could be modified by ubiquitination. Because Smad6 was co-localized in the nucleus with Tbx6, it is possible that Smad6-mediated Tbx6 degradation takes place in the 26S proteasome, which is also located in the nucleus.

Finally, the current study sheds light on the functional specificity and diversity of T-box proteins, which are crucial for a variety of developmental processes. The functional differences between T-box proteins are in part due to the variable affinities for their binding sites but also to their distinct interactions with other regulators. For instance, the T-box family member Tbx5 interacts with the cardiac lineage marker Nkx2.5 and zinc finger protein GATA4, synergistically promoting cardiomyocyte differentiation (42, 43). In this report, we point out that Tbx6 interacts with an inhibitory Smad at residues 90–180, whereas Xenopus Brachyury shares low protein sequence similarity within this region and thereby loses its ability to bind Smad6. Additionally, Tbx6 fails to associate with Smad1, presumably because of the absence of a HLL(S/N)AV(E/Q) motif at its N terminus, which is required for the specific interaction of Xenopus Brachyury with Smad1 (19). Hence, these findings suggest that the distinct roles of T-box proteins are conferred by their variable affinities for different cofactors. However, further investigation is still necessary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues Wei Mo, Liang Zhang, Yang-Er Ye, and Min-Ying Liu for helpful discussion and technical assistance. We are grateful to Dr. Xin-Hua Feng (Baylor College of Medicine) for kindly providing the Smad6 deletion mutants; Dr. Joan Massagué (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for kindly providing Smurf1 constructs; and Dr. M. Noda (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Japan) for generously sending TT-D6 cells. We especially thank Dr. Ye-Guang Chen (Tsinghua University, China) and Dr. Di Chen (University of Rochester) for expert comments.

This work was supported by Grants 2005CB522704, 2007CB947903, and 2009CB941101 from the National Basic Research Program of China and Grants 30623003, 30771077, and 30871411 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (to X. D.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- TK

- thymidine kinase

- RT

- reverse transcriptase

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MH

- Mad homology

- E3

- ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hogan B. L. (1996) Genes Dev. 10,1580–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen D., Zhao M., Mundy G. R. (2004) Growth Factors 22,233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massagué J. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67,753–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massagué J., Chen Y. G. (2000) Genes Dev. 14,627–644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massagué J., Wotton D. (2000) EMBO J. 19,1745–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Showell C., Binder O., Conlon F. L. (2004) Dev. Dyn. 229,201–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naiche L. A., Harrelson Z., Kelly R. G., Papaioannou V. E. (2005) Annu. Rev. Genet. 39,219–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Packham E. A., Brook J. D. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12,37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman D. L., Agulnik I., Hancock S., Silver L. M., Papaioannou V. E. (1996) Dev. Biol. 180,534–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman D. L., Papaioannou V. E. (1998) Nature 391,695–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamaguchi T., Yabe S., Uchiyama H., Murakami R. (2004) Dev. Biol. 265,355–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada M., Revelli J. P., Eichele G., Barron M., Schwartz R. J. (2000) Dev. Biol. 228,95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchiyama H., Kobayashi T., Yamashita A., Ohno S., Yabe S. (2001) Dev. Growth Differ. 43,657–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szeto D. P., Kimelman D. (2004) Development 131,3751–3760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mei W., Yang J., Tao Q., Geng X., Rupp R. A., Ding X. (2001) FEBS Lett. 505,47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin G. F., Geng X., Chen Y., Qu B., Wang F., Hu R., Ding X. (2003) Dev. Dyn. 226,51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Z., Li J., Zhen C., Feng L., Ding X. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335,676–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lou X., Fang P., Li S., Hu R. Y., Kuerner K. M., Steinbeisser H., Ding X. (2006) Cell Res. 16,771–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messenger N. J., Kabitschke C., Andrews R., Grimmer D., Núñez Miguel R., Blundell T. L., Smith J. C., Wardle F. C. (2005) Dev. Cell 8,599–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanyu A., Ishidou Y., Ebisawa T., Shimanuki T., Imamura T., Miyazono K. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155,1017–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman D. L., Cooper-Morgan A., Harrelson Z., Papaioannou V. E. (2003) Mech. Dev. 120,837–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y., Lin G. F., Hu R., Chen Y., Ding X. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 310,121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen R., Chen M., Wang Y. J., Kaneki H., Xing L., O'Keefe R. J., Chen D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281,3569–3576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murakami G., Watabe T., Takaoka K., Miyazono K., Imamura T. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14,2809–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White P. H., Chapman D. L. (2005) Genesis 42,193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuhiko Y., Haraguchi S., Kitajima S., Takahashi Y., Kanno J., Saga Y. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103,3651–3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katagiri T., Yamaguchi A., Komaki M., Abe E., Takahashi N., Ikeda T., Rosen V., Wozney J. M., Fujisawa-Sehara A., Suda T. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 127,1755–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto N., Akiyama S., Katagiri T., Namiki M., Kurokawa T., Suda T. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238,574–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salingcarnboriboon R., Yoshitake H., Tsuji K., Obinata M., Amagasa T., Nifuji A., Noda M. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 287,289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishida W., Hamamoto T., Kusanagi K., Yagi K., Kawabata M., Takehara K., Sampath T. K., Kato M., Miyazono K. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275,6075–6079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Q., Wei X., Zhu T., Zhang M., Shen R., Xing L., O'Keefe R. J., Chen D. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282,10742–10748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y., Wang Y. F., Jayaraman L., Yang H., Massagué J., Pavletich N. P. (1998) Cell 94,585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai S., Shi X., Yang X., Cao X. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275,8267–8270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai S., Cao X. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277,4176–4182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Datta P. K., Chytil A., Gorska A. E., Moses H. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273,34671–34674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Datta P. K., Moses H. L. (2000) Mol. Cell Biol. 20,3157–3167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann M., Schuster-Gossler K., Watabe-Rudolph M., Aulehla A., Herrmann B. G., Gossler A. (2004) Genes Dev. 18,2712–2717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wittler L., Shin E. H., Grote P., Kispert A., Beckers A., Gossler A., Werber M., Herrmann B. G. (2007) EMBO Rep. 8,784–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reshef R., Maroto M., Lassar A. B. (1998) Genes Dev. 12,290–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer R. J. (2000) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1,145–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pickart C. M. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70,503–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiroi Y., Kudoh S., Monzen K., Ikeda Y., Yazaki Y., Nagai R., Komuro I. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28,276–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garg V., Kathiriya I. S., Barnes R., Schluterman M. K., King I. N., Butler C. A., Rothrock C. R., Eapen R. S., Hirayama-Yamada K., Joo K., Matsuoka R., Cohen J. C., Srivastava D. (2003) Nature 424,443–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.