Abstract

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy is a surgical procedure used worldwide for the treatment of grade III and IV hemorrhoids in all age groups. However, life-threatening complications occur occasionally. The following case report describes the development of pelvic sepsis after stapled hemorrhoidopexy. A literature review of techniques used to manage major septic complications after stapled hemorrhoidopexy was performed. There is no standardized treatment currently available. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy is a safe, effective and time-efficient procedure in the hands of experienced colorectal surgeons.

Keywords: Hemorrhoids, Hemorrhoids/treatment, Sepsis, Stapled hemorrhoidopexy, Circular mucosectomy

INTRODUCTION

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy is used worldwide for the treatment of grade III and IV hemorrhoids, because it is a safe, effective and time-efficient procedure for all age groups[1,2]. However, life-threatening complications occur occasionally[3,4]. We carried out a literature search to review the treatment options for managing major septic complications after stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Since there is no standardized treatment, we propose diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for this complication.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old female patient was referred to our hospital with grade III-IV hemorrhoids. She underwent a circular mucosectomy by a stapling device (PPH03, 33 mm, Ethicon EndoSurgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Clinical examination showed fully intact doughnuts. The patient recovered well, and left the hospital without any complaints.

After 4 d, she was readmitted with fever and pain over the lower abdomen, without any rebound tenderness. Laboratory tests showed leucocytes count of 16.9 × 109/L (reference 4.0-10 × 109/L) and a C-reactive protein of 298 mg/L (reference CRP < 6 mg/L). Computer tomography (CT) scan with rectal contrast showed a presacral fluid collection with gas extending to the retroperitoneal space (Figures 1 and 2). A rectal perforation with a presacral abscess was diagnosed. Laparotomy showed the presence of hematomas in the sigmoid mesentery and in the retroperitoneum. A loop ileostomy was performed. Rectal examination showed a perforation at the right dorsolateral side of the rectum. A Foley catheter was inserted into the presacral space. Postoperatively, the patient received antibiotics, and she was discharged after 19 d.

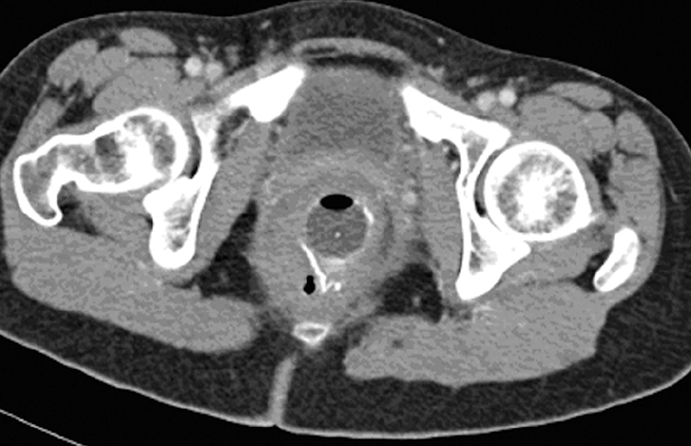

Figure 1.

Axial image CT scan: Free air near the staple line.

Figure 2.

Sagital reconstruction CT scan with rectal contrast: presacral abscess.

DISCUSSION

During the last decade, stapled hemorrhoidopexy has become increasingly popular for the treatment of symptomatic grade III and IV hemorrhoids. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy does not remove the hemorrhoids, but rather a strip of mucosa and submucosa at the top of the hemorrhoids is removed. An anastomosis of the proximal and distal mucosa and submucosa is made through the staple line, approximately 4 cm above the dentate line[4,5].

Septic complications after stapled hemorrhoidopexy such as in the present case are rare. Brusciano et al[5] evaluated the causes of reintervention in patients with complicated or failed stapled hemorrhoidopexy. The reoperation rate was 5.1%. Anorectal sepsis was the indication for reintervention in 16.9% of patients, which is 0.9% of all patients, whereas retro-rectal hematoma occurred in 1.5% patients. An survey of 224 departments of surgery in Germany, involving a total of 4635 stapled hemorrhoidopexies, revealed three cases of rectal perforation, one case of a large retro-rectal hematoma and one patient with lethal sepsis from Fournier’s gangrene[6]. The cause of severe sepsis and retroperitoneal sepsis associated with both surgical and non-surgical treatment of hemorrhoids remains uncertain. It has been postulated that stapling itself may allow bacterial entry into the perirectal region. Full-thickness wall stapling may also allow organism to reach the perirectal space. By contrast, the presence of muscle tissue in the excised specimens is not uncommon. Several studies have observed muscle tissue in the doughnuts in 100% of patients[7,8].

There is no standard treatment for sepsis after stapled hemorrhoidopexy, and several different approaches have been used. Molloy and Kingsmore[3] reported a case of retroperitoneal sepsis, which required exploratory laparotomy and an end colostomy. The presacral space was drained. The staple line appeared to be normal and no rectal perforation was identified. Maw et al[9] reported a case of retroperitoneal sepsis, which was treated with intravenous antibiotics alone, without any surgical intervention. The staple line appeared to be intact on rectal examination. Wong et al[10] described a patient who had an interrupted line and a rectal perforation just above the peritoneal reflection resulting in a fecal peritonitis. The patient was treated with an end colostomy. Pessaux et al[11] reported a patient with an incomplete staple line, resulting in pelvic sepsis, that was treated with debridement and a temporary end colostomy.

When the staple line is intact, a conservative approach appears to be sufficient. However, surgery is mandatory when a rectal tear is diagnosed or the staple line is not intact. In our opinion, the latter situation compares with rectal perforation. Several different treatment approaches have been employed for the management of rectal perforations. In a recent review, de Feiter et al[12] noted that surgery is not always indicated for rectal perforation occurring after a barium enema. Intramural or a small retroperitoneal perforation can be treated with conservative measures such as bowel rest, total parenteral feeding, intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Surgical debridement is only required in patients not responding to conservative treatment, and in patients with intramural abscesses. Perirectal abscesses always require drainage. By contrast, conservative treatment has been used even for major rectal perforation occurring after barium enema. This approach can be employed if the perforation was restricted to the retroperitoneum, the patient’s general condition was good, the bowel was clean and the rectal tear was minor[13].

Di Venere et al[14] have attempted to standardize the treatment of rectal perforation. These workers argued that intraperitoneal rectal perforation should be considered as colonic or sigmoid perforation. Such patients should undergo surgical treatment depending upon the size of the bowel injury, the duration of intestinal spillage, comorbid conditions, and the surgeon’s experience. Hartmann procedure was considered as the most appropriate technique if the wound exceeded 50% of the bowel circumference, with extended bowel wall loss and severe peritoneal contamination. Smaller lesions with less peritoneal contamination were considered more suitable for primary closure of the rectal wound followed by a diverting colostomy. A loop colostomy was proposed as the only possible treatment in severely ill and older patients with extraperitoneal rectal perforation. In all other cases of extraperitoneal rectal perforations, these workers recommended primary closure of the rectal wound with a diverting colostomy.

We prefer not to perform a primary closure of such perforations. In patients with intraperitoneal perforation, we recommend resection of the injured rectum, with anastomosis, and with or without a diverting (loop) colostomy or ileostomy. If severe peritonitis is present, we employ the Hartmann procedure. In patients with extraperitoneal perforation, the treatment is based on the extent of the perforation. Antibiotics and bowel rest as sole therapy is used for small perforations. For large perforations and/or severe sepsis, a diverting (loop) colostomy or ileostomy is performed. Closure of the rectal perforation is not an option, because adequate drainage is the treatment of choice for (presacral) abscesses.

In conclusion, stapled hemorrhoidopexy is a safe, effective and time-efficient procedure. However, life-threatening complications can occur. There is no standard treatment for the management of pelvic sepsis. We recommend that only experienced colorectal surgeons, who are familiar with the technique and its complications, should perform such procedures. Further studies are needed to investigate and classify the best treatment for pelvic sepsis after stapled hemorrhoidopexy.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Avdyl S Krasniqi, Associate Professor, Department of Abdominal Surgery, University Clinical Centre of Kosova, “Uke Sadiku” 13A, QKUK - Klinika e Kirurgjise, Fakulteti i Mjekesise, Universiteti i Prishtines, Prishtine 10000, Yugoslavia

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Anand BS E- Editor Zhang WB

References

- 1.Lan P, Wu X, Zhou X, Wang J, Zhang L. The safety and efficacy of stapled hemorrhoidectomy in the treatment of hemorrhoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of ten randomized control trials. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:172–178. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0786-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson DB, DiSiena MR, Fanelli RD. Circumferential mucosectomy with stapled proctopexy is a safe, effective outpatient alternative for the treatment of symptomatic prolapsing hemorrhoids in the elderly. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1990–1995. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molloy RG, Kingsmore D. Life threatening pelvic sepsis after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Lancet. 2000;355:810. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02208-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stamos MJ. Stapled hemorrhoidectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:627–628. doi: 10.1007/BF03239965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brusciano L, Ayabaca SM, Pescatori M, Accarpio GM, Dodi G, Cavallari F, Ravo B, Annibali R. Reinterventions after complicated or failed stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1846–1851. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0721-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herold A, Kirsch JJ. Painafter stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Lancet. 2000;356:2187; author reply 2190. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheetham MJ, Mortensen NJ, Nystrom PO, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Persistent pain and faecal urgency after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Lancet. 2000;356:730–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fazio VW. Early promise of stapling technique for haemorrhoidectomy. Lancet. 2000;355:768–769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maw A, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F. Retroperitoneal sepsis complicating stapled hemorrhoidectomy: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:826–828. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6304-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong LY, Jiang JK, Chang SC, Lin JK. Rectal perforation: a life-threatening complication of stapled hemorrhoidectomy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:116–117. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pessaux P, Lermite E, Tuech JJ, Brehant O, Regenet N, Arnaud JP. Pelvic sepsis after stapled hemorrhoidectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:824–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Feiter PW, Soeters PB, Dejong CH. Rectal perforations after barium enema: a review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madhala O, Greif F, Cohen M, Lelcuk S. Major rectal perforations caused by enema: is surgery mandatory? Dig Surg. 1998;15:270–272. doi: 10.1159/000018627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Venere B, Testini M, Miniello S, Piccinni G, Lissidini G, Carbone F, Bonomo GM. Rectal perforations. Personal experience and literature review. Minerva Chir. 2002;57:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]