Abstract

Background

Alcohol use frequently onsets and shows rapid growth during the adolescent years, but few studies have examined growth in two indicators, namely in use and in volume given use, with prediction from key risk factors measured across the adolescent years.

Methods

Based on a dynamic developmental systems framework, we predicted that the general risk pathway associated with the development of antisocial behavior (namely poor parental practices and antisocial behavior/deviant peer association) would be associated with both indicators of use in Grade 6. Specific proximal social influences, namely alcohol use by parents and peers, were also hypothesized, with growth in peer use of alcohol expected to be predictive of growth. Predictors were assessed by youth, parent, and teacher reports, with alcohol use and volume assessed yearly by youth self-reports. Models were tested separately for the 3-year middle school period and the 4-year high school period. Hypotheses were tested for the Oregon Youth Study sample of approximately 200 at-risk boys.

Results

Findings indicated that alcohol use by both parents and peers were associated with initial levels of alcohol use and volume, but increases in peer use predicted growth in these indicators. Parental monitoring showed a protective effect on growth in volume in high school.

Conclusion

Alcohol use by members of the adolescent’s social network is critical to initiation of use, and peer use is critical to growth. With these predictors specific to alcohol use in the model, none of the general risk factors for antisocial behavior were significant.

Keywords: alcohol growth, adolescence, monitoring, antisocial behavior, parent alcohol use, peer alcohol use

1. Introduction

Alcohol use frequently onsets and shows rapid growth during the adolescent years (Duncan et al., 2006). Almost one half of eighth graders report initiation of alcohol use and 13% report recent heavy episodic drinking (Maggs and Schulenberg, 2006), and use in middle school predicts alcohol abuse or dependence at age 21 years (Guo et al., 2000). Therefore, a better understanding of factors related to the onset and escalation of alcohol use across adolescence is of critical importance.

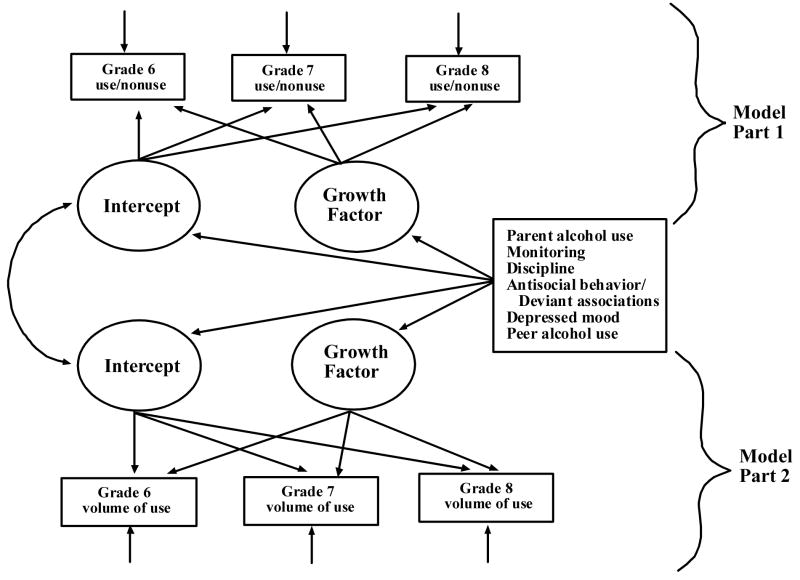

We have developed a dynamic developmental systems (DDS) framework (Capaldi et al., 2005) that seeks to explain onset and changes in behaviors such as substance use from (a) general developmental risk pathways (e.g., parental monitoring and poor discipline, boy’s antisocial behavior and deviant peer associations, boy’s depressed mood) and (b) social influences from key developmental interactants that are specifically related to the outcome under study (e.g., use of alcohol by parents and peers). The goal of the current study was to examine prediction models of growth in alcohol use for the middle and high school periods, spanning ages 11–12 to 17–18 years, using the Oregon Youth Study (OYS) sample of boys, who were at risk for conduct problems because of their disadvantaged neighborhoods. Models were tested by using a two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous data (Olsen and Schafer, 2001), which has been used in recent studies of alcohol use at adolescence (e.g., Blozis et al, 2007; Brown et al., 2005). Part I involved prediction to use vs. nonuse; Part II involved prediction to yearly volume given use.

It has been observed with other U.S. samples that the slope of the increase in frequency of alcohol use rises in the first year of high school, and thus there is discontinuity from middle to high school in growth rate. One strategy to address this issue has been to examine piecewise models of growth across these two developmental periods (Brown et al., 2005; Li et al., 2001). In the current study, because of model size and complexity, the issue was addressed by estimating models separately for middle school (Grades 6–8) and high school (Grades 9–12). To test changing influences over time (e.g., increases in peer alcohol use) more systematically, time-varying influences (i.e., change scores of the predictors from the prior time period) on both indicators of alcohol use were examined, in addition to prospective predictors from the initial years of middle and high school (Grades 6 and 9, respectively).

1.1. The Etiology of Alcohol Use at Adolescence

Risk factors associated with problem behavior more generally have been found to be associated with alcohol use at adolescence, including parental monitoring and discipline practices and the adolescent’s antisocial behavior and association with deviant peers. Parental supervision or monitoring and discipline, along with related constructs of parenting (e.g., clear behavioral expectations, low family conflict), have been found protective against alcohol use during adolescence (Getz and Bray, 2005). Antisocial behavior has been found in numerous studies to be predictive of early alcohol use (Dishion et al., 1999; Getz and Bray, 2005), as has deviant peer association (Li et al. 2001).

The DDS model emphasizes the importance of influences in close social relationships that are specific to the behavior under study and the variation in sources of such influence by developmental stage. Whereas parents are influential in childhood, and parental alcohol use is related to adolescent substance use (e.g., Chassin et al., 1993), peers have arguably the strongest influence on problem behaviors at adolescence (e.g., Dishion et al., 1996). Duncan et al. (2006) found that higher levels of parental alcohol use were associated with higher initial levels of use, whereas higher levels of peer deviance and friends’ encouragement of alcohol use were related to increases in alcohol use from ages 9–16 years, controlling for general risk factors.

The self-medication hypothesis posits that individuals will attempt to alleviate distressing symptoms by substance use (Khantzian, 1985), yet the association of depressed mood with growth in alcohol use at adolescence has been little examined. There is some evidence of an association between depression in childhood and levels of subsequent alcohol use in adolescence and young adulthood (Crum et al., 2008) for those who used any alcohol. However, in the Crum et al. study, depressed mood in childhood was assessed by only four items, two of which were nonspecific to depressed mood (namely “being in a bad mood” and “feeling crabby or cranky”), and the conduct problem control was a dichotomous measure rather than a continuous score. Fleming et al. (2008) found that higher levels of depressive symptoms in early adolescence predicted less increase in alcohol use through ages 16–17 years. Peers are posited to be a critical factor in alcohol use at adolescence, and depressed mood is related to poor social relations at this age (Capaldi, 1991); thus, we expected that depressed mood might be a protective rather than a risk factor.

1.2. Summary of Hypotheses

The general risk pathway associated with antisocial behavior (namely poor parental practices and antisocial behavior/deviant peer association) will predict the intercepts of the two indicators of alcohol use (i.e., use and volume of use) in middle school.

Of these factors, parental monitoring is expected to be protective against growth in both of the use indicators in the middle and high school periods.

Alcohol use by both parents and peers will predict initial levels of both indicators of use in middle and high school.

Change in levels of use by peers but not by parents will be predictive of growth in use and volume of use over time in middle and high school.

Specific, rather than general, risk factors will be predictive of the high school intercepts of the alcohol use indicators (controlling for middle school use).

Depressive symptoms will be associated with less growth in the two indicators of alcohol use across adolescence.

2. Method

2.1. Sample

The entire fourth grade of boys (ages 9–10 years) and their families from schools with higher incidences of juvenile delinquency in the neighborhood for a medium-sized metropolitan area (Eugene-Springfield in Oregon) were invited to participate in the study. The recruitment rate was 74.4% (N = 206), and retention was at least 97% at each wave through the senior year of high school (Capaldi et al., 1997). The sample size of boys was 203 (99%) in Grade 6 and 201 (98%) in Grade 12 (age 17–18 years). The sample was predominantly Caucasian (90%), with 10% being African-American, Hispanic, Native-American, or mixed race, and 75% lower or working class.

2.1.1 Parent participation

At Grade 6, family composition included intact parents (38%), single-parent (19%), step-parent (29%), and multiple parent transition (14%). The proportion of single-parent families was between 14% and 17% through Grade 12. Parents living with the youth were invited to participate at each wave. At Grade 6, 191 mothers and 140 fathers participated, and at Grade 12, 188 mothers and 128 fathers participated. Both parents participated in 53% to 64% of the families across the period. The values for mothers and fathers were computed separately, standardized for each construct, and then the mean was computed.

2.2. Procedures

The OYS involved yearly data collection with alternating major (Grades 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) and minor waves. The major assessments were multimethod and multiagent, including interviews and questionnaires for the youth and parents at the Oregon Social Learning Center (the appointment lasted approximately 2 hours), brief telephone interviews that provided multiple samples of recent behaviors (a total of six, 3 days apart), unstructured home observations (a total of three 45-minute observations at Grades 4 and 6 only), videotaped family problem-solving interaction tasks, school data (including teacher questionnaires and records data), and court records data. Rating scales were filled out by the interviewer on their impressions of the youth’s behavior and by the observers on their impressions of family members’ behavior. Minor waves were more limited in scope and focused mainly on the dependent variables, including measures of alcohol use. The data in the current study were taken from Wave 3 (ages 11 to 12 years, Grade 6) through Wave 9 (ages 17 to 18 years, Grade 12), over a period of 7 years. Family consent was mandatory. Participants were compensated for their time at each assessment wave.

3. Measures

3.1. Dependent Variables

The alcohol indicators were assessed by the boys’ reports in the youth’s yearly interview of any use, frequency, and typical amount of use of alcohol, including use of beer, wine, or hard liquor, over the past year during middle school (ages 11 to 14 years) and high school (ages 15 to 18 years). For each type of alcohol, the youth was asked (a) whether he had drunk any in the past year (e.g., “Have you tried beer, even a sip, in the last year?”); (b) for users, the number of times used in the past year (any responses over 365 were recoded to 365); and (c) how much he usually drank each time (i.e., less than one unit, one unit, two units, three units, four to five units, six units or more). The unit of volume was one can or bottle for beer, one glass for wine, and one drink (shot) for hard liquor. Frequency was multiplied by the amount usually consumed – taking into account the serving sizes for beer, wine, and hard liquor due to differences across these drink categories in ethanol content – to create the approximate yearly volume scores for beer, wine, and hard liquor separately, and then these three values were summed to create the total yearly alcohol volume score. The dependent variables were log transformed prior to use in the modeling analysis to reduce skew and to improve scaling for the Mplus maximum likelihood estimation procedure.

3.2. Predictor Construct Development Strategy

The construct development strategy used in the study has been described in detail elsewhere (e.g., Dishion et al., 1999; Patterson and Bank, 1986) and involved reliability and validity assessments. To form a construct, scales that met established criteria were standardized to ensure equal weight and aggregated by computing the mean of the scales.

3.2.1. Middle School Model

Grade 6 intercepts and Grade 6 to 8 slopes were predicted by the Grade 6 constructs. The change scores of the predictors (from Grades 6 to 8) were also used in predicting to the slopes.

3.2.2. High School Model

Grade 9 intercepts and Grade 9 to 12 slopes were predicted by the Grade 9 constructs. The change scores used in the high school model are described in more detail in the analytic plan.

Shown in Table 1 for Grades 6 and 10, providing examples of the middle and high school periods, are the number of items, sample items, standardized item alphas, and correlations for each of the scales within the constructs. Further description of each construct is provided below (note that references are provided for a questionnaire the first time it is mentioned only). Technical reports that provide further details are available from the authors.

Table 1.

Representative Measures from Middle and High School Periods

| Construct and Wave | Assessment Instrument | Respondent | Number of items | Sample item | Cronbach’s alpha | Pearson corr. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisocial Behavior and Association | |||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Mean of Antisocial Behavior and Deviant Peer Association | .73 | |||||

| Wave 7 (Grade 10) | Mean of Antisocial Behavior and Deviant Peer Association | .78 | |||||

| Antisocial Behavior | |||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Construct | .88 | |||||

| Home Observations, Family Process Code | Coder | 16 | Mean of 16 negative behavior category duration proportions | ||||

| Home Observer Impressions | Observer | 4 | Youth demonstrated a hostile, arrogant, noncompliant attitude toward mother | .83 | |||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Overt | M,F | 7,7 | Gets in many fights | .79,.79 | .59 | ||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Covert | M,F | 8,7 | Steals at home | .69,.77 | .51 | ||

| OCAQ questionnaire, Overt | M,F | 11,10 | Talks back to an adult | .86,.89 | .69 | ||

| OCAQ questionnaire, Covert | M,F | 21,26 | Takes off without permission | .83,.84 | .60 | ||

| Telephone Interview, Overt | Parent | 7 | In the last 24 hrs, did your son scream or yell? | .79 | |||

| Peers Questionnaire | M,F | 1,1 | How often does your son get in conflicts with other kids around the home? | .31 | |||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Overt | Teacher | 11 | Argues a lot | .92 | |||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Covert | Teacher | 8 | Lying or cheating | .85 | |||

| Teacher Peer Social Skills Questionnaire | Teacher | 1 | How often does he exert negative influence on his friends? | ||||

| Interview, Overt | Youth | 9 | How often do you hit or threaten to hit? | .80 | |||

| Interview, Covert | Youth | 24 | How often do you make excuses to get out of trouble? | .87 | |||

| Telephone Interview, Overt | Youth | 8 | In the last 24 hrs, did you tease anyone? | .89 | |||

| Interview, Impressions | Interviewer | 1 | How likely is it that this boy will have future trouble with the police? | ||||

| Wave 7 (Grade 10) | Construct | .74 | |||||

| Agent Indicator | Parent | .74 | |||||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Overt | M,F | 7,7 | Disobedient at home | .82,.74 | .65 | ||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Covert | M,F | 8,8 | Destroys others things | .84,.87 | .73 | ||

| Peers Questionnaire | M,F | 1,1 | How often does your son get in conflicts with other kids around the home? | .24 | |||

| Agent Indicator | Teacher | .87 | |||||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Overt | Teacher | 11 | Cruelty, bullying, meanness to others | .93 | |||

| Child Behavior Checklist, Covert | Teacher | 8 | Lying or cheating | .86 | |||

| Teacher Peer Social Skills Questionnaire | Teacher | 1 | How often does he exert negative influence on his friends? | ||||

| Interview, Impressions | Interviewer | 1 | How likely is it that this boy will have future trouble with the police? | ||||

| Deviant Peer Association | |||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Construct | .67 | |||||

| Child Behavior Checklist | M,F | 1,1 | Hangs out with kids who get in trouble | .41 | |||

| OCAQ Questionnaire | M,F | 2,2 | Does your son hang out with kids who steal? | MF r = .33 | .07,.22 | ||

| Child Behavior Checklist and | Teacher | 1+3 | Does this student associate with kids involved in stealing or vandalism? | .90 | |||

| Teacher Peer Social Skills Questionnaire (TPRSK) | |||||||

| Interview and Describing Friends Questionnaire | Youth | 7+9 | During the last year, how many of your friends stole something worth <$5? | .80 | |||

| Wave 7 (Grade 10) | Construct | .76 | |||||

| Child Behavior Checklist and Peers Questionnaire | M,F | 1+2,1+2 | Hangs out with kids who get in trouble | .83,.84 | .71 | ||

| Child Behavior Checklist and TPRSK Questionnaire | Teacher | 1+3 | Does this student associate with kids involved in stealing or vandalism? | .92 | |||

| Interview and Describing Friends Questionnaire | Youth | 10+5 | During the past year, how many of your friends stole something worth <$5? | .86 | |||

| Depressive Symptoms | |||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Construct | .62 | |||||

| Child Behavior Checklist | M,F | 8,8 | Feels or complains that no one loves him | .76,.73 | .48 | ||

| Child Behavior Checklist | Teacher | 8 | Unhappy, sad or depressed. | .67 | |||

| Home Observation, Impressions | Observer | 1 | Boy seemed sad, down or depressed | ||||

| Child Depression Rating Scale | Youth | 18 | I feel so sad I can hardly stand it. | .76 | |||

| Telephone Interview | Parent | 1 | In the last three days, was your son depressed? | ||||

| Telephone Interview | Youth | 1 | In the last three days, have you been sad, down or depressed? | ||||

| Wave 7 (Grade 10) | CESD-D | Youth | 20 | During the past week, I felt sad. | .86 | ||

| Peer Alcohol Use | |||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Construct | .46 | |||||

| Interview | Youth | 6 | How often do your friends usually drink? | .88 | |||

| Describing Friends Questionnaire | Youth | 1 | In the last year, have you seen kids around your age drinking alcohol? | ||||

| Wave 7 (Grade 10) | Construct | .47 | |||||

| Interview | Youth | 8 | How often do your friends usually drink? | .87 | |||

| Describing Friends Questionnaire | Youth | 1 | In the last year, have you seen kids around your age drinking alcohol? | ||||

| Parent Monitoring | |||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Construct | .62 | |||||

| Interview | Mother | 5 | How often is an adult home within 1 hr. after school? | .64 | |||

| Interview | Youth | 5 | Before going out, how often do you tell your parents when you will be back? | .64 | |||

| Telephone Interview | Parent | 2 | In the last 24 hrs., did you talk to your son about what he did today? | .11 | |||

| Telephone Interview | Youth | 2 | During the last 24 hrs., did your parents talk to you about your plans for tomorrow? | .58 | |||

| Interview, Impressions | Interviewer | 3 | How carefully does this parent monitor the child? | .60 | |||

| Wave 7 (Grade 10) | Construct | .75 | |||||

| Interview, Parent Monitoring | M,F | 12,15 | On the average, how many hours per week is your son alone or with siblings only? | .82,.79 | .73 | ||

| Interview, Impressions | Interviewer | 1,1 | This parent seemed to monitor the child carefully. | .77 | |||

| Interview | Youth | 9 | Your parents let you go any place you please without asking. | .79 | |||

| Interview, Impressions | Interviewer | 1 | This boy seems to be well supervised by his parents. | ||||

| Parent Discipline | |||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Construct | .76 | |||||

| Interview, Parent Monitoring | M,F | 10,10 | How often is your son able to get out of a punishment when he really sets his mind to it? | .80,.79 | .48 | ||

| Telephone Interview | Parent | 1 | Did he do anything (in last 3 days) that he should have been disciplined for (but wasn’t)? | ||||

| Home Observations, Impressions | Observer | 7,7 | Mother seemed to discipline child well. | .90,.88 | .83 | ||

| Interview, Impressions | Interviewer | 1,1 | How would you rate this parent on discipline? | .62 | |||

| Home Observations, Family Process Code | Coder | 1,1 | Nattering | .36 | |||

| Interview, Impressions | Interviewer | 1 | Did the child seem to be well disciplined by his parents? | ||||

| Wave 5 (Grade 8) | Construct | .59 | |||||

| Problem-Solving Task, Family Process Coder | |||||||

| Impressions | Coder | .59 | |||||

| of Mother discipline | Coder | 2 | M .65 | ||||

| of Father discipline | Coder | 3 | .64 | ||||

| Global family ratings | Coder | 3 | .64 | ||||

| Interview | Youth | 5 | How often do your parents agree on how to punish you? | .59 | |||

| Problem-Solving Task, Family Process Code, M,F | Coder | Rate per minute: aversive codes in any valence and neutral codes in negative valence | .45 | ||||

| Parent Alcohol Use | Indicator | ||||||

| Wave 3 (Grade 6) | Substance Use Questionnaire | M,F | 1,1 | How often do you drink alcohol? | .50 | ||

| Wave 7 (Grade 10) | Substance Use Questionnaire | M,F | 1,1 | How often do you drink alcohol? | .43 | ||

Note. M = mother, F = father

3.3. Grade 6 Constructs

3.3.1. Youth antisocial behavior and deviant peer associations

Scales for antisocial behavior were created from parent (a. Child Behavior Checklist – CBC-L – Achenbach and Edelbrock, 1983; b. Overt Covert Antisocial Behavior Questionnaire – OCAQ – Oregon Social Learning Center, 1984a; c. Telephone Interview; d. Peers Questionnaire), teacher (a. Teacher Report Form – TRF – Achenbach, 1981; b. Teacher Peer Social Skills Questionnaire – TPRSK –Dishion and Capaldi, 1985b; Walker and McConnell, 1988), youth (a. Telephone Interview; b. annual interview), interviewer (Interviewer Rating Scales), and home observations (a. Youth Negative Behavior from the Family Process Code; b. observer ratings from the home observations). Cronbach’s alpha for these indicators at Grade 6 was .88.

Deviant peer associations were assessed by parent (CBC-L and OCAQ), teacher (TRF and TPRSK), and youth self-report (youth interview and Describing Friends Questionnaire; Dishion and Capaldi, 1985a). Cronbach’s alpha for these indicators at Grade 6 was .67.

Antisocial behavior and deviant peer association are highly associated and play similar roles in predicting problem outcomes, including substance use (Capaldi et al., 2002; Dishion et al., 1999). The constructs were strongly associated at Grade 6 (r = .73, p <.001). Similar results for the two as separate predictors were found in preliminary analyses, thus a combined construct of antisocial behavior and deviant peer association was used in subsequent analyses.

3.3.2. Youth depressive symptoms

Scales were created from parent (CBC-L; Telephone Interview), teacher (TRF), home observer ratings, and youth reports (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale – CES-D – Radloff, 1977; Telephone Interview). Cronbach’s alpha for the indicators at Grade 6 was .62.

3.3.3. Peer alcohol use

The frequency and amount of peer alcohol use was assessed by scales from youth reports (Youth Interview; Describing Friends Questionnaire). Substantial associations have been found between perceived and actual peer use (Wilks et al., 1989). The scale items assessed alcohol use-related behaviors such as getting drunk, selling or giving alcohol to peers, and general frequency of use. As shown in Table 1, the correlation between the two Grade 6 Peer Alcohol Use indicators was .46. Although not used in the current study as they were only available at limited grades, peer reports of their own alcohol use were available at Grades 8, 10, and 12. Correlations between youth reports of peer use and peer self-reports were .42, .44, and .37, respectively (all p < .001), indicating reasonable validity of youth report of peer alcohol use. Note that peer reports were only for their own alcohol use, whereas the youth reports cover all their peers.

3.3.4. Parent alcohol use

Parental frequency of alcohol use was assessed by parental reports on the Substance Use Questionnaire (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1984b). At Grade 6, the correlation between the mother and father items was .50 (p < .001).

3.3.5. Parental monitoring

Scales were created from the Mother Interview, Youth Interview, interviewer ratings, and the Telephone Interviews of parent and youth. Cronbach’s alpha for the indicators at Grade 6 was .62.

3.3.6. Parental discipline

Scales were created from parent (a. interview; b. Telephone Interview), home observer ratings, the Family Process Code, and parent and youth interviewer ratings. Cronbach’s alpha for these computed indicators was .76.

3.4. Representative High School Constructs from Grade 10

3.4.1. Youth antisocial behavior and deviant association

Scales were created from parent (Peers Questionnaire and CBC-L), teacher (TRF and TPRSK), and interviewer ratings from the Youth Interviewer. Cronbach’s alpha for these indicators was .74.

Deviant peer association was assessed by parent (CBC-L and Peers Questionnaire), teacher (TRF and TPRSK), and youth report (Youth Interview and Describing Friends Questionnaire). Cronbach’s alpha for the indicators was .76. The antisocial behavior and deviant peer association constructs were highly associated (r = .78, p <.001) and, as for the middle school model, were combined for the high school model.

3.4.2. Youth depressive symptoms

Youth’s self-report (CESD only) was used. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .86.

3.4.3 Peer alcohol use

Scales from youth report (Youth Interview and Describing Friends Questionnaire) were used. The correlation of the two indicators was .47 (p < .001).

3.4.4. Parent alcohol use

Parental reports from the Substance Use Questionnaire were used. The correlation of the two indicators was .43 (p < .001).

3.4.5. Parental monitoring

Scales were created from the Parent Interview, parent interviewer ratings, Youth Interview, and youth interviewer ratings. Cronbach’s alpha for the indicators was .75.

3.4.6. Parental discipline

Parental discipline was not extensively measured during the high school period. Measures included an observational indicator of aversive behaviors for each parent obtained from the Family Process Code for the Problem-Solving Task; by indicators of mother, father, and global family discipline formed from the Family Process Coder ratings; and by a scale of items obtained from the Youth Interview. Cronbach’s alpha for the indicators was .59.

3.5. Analysis Plan

Olsen and Schaffer (2001) proposed a growth model for semicontinuous outcomes (e.g., alcohol use) that have a substantial portion of identical values, typically zero (e.g., nonusers), and then a continuous and typically skewed distribution for the rest of the values (representing variations in drinking levels among users). Part I is a growth model for a binary variable that indicates any alcohol use versus nonuse. Part II is a standard growth model for, in the current study, volume of alcohol use given any use at all, and individuals only have a non-missing score at a particular assessment if the alcohol score is above zero.

The basic structure of the two-part model tested in middle school is depicted in Figure 1, illustrating prediction to intercept and slope of both use and volume of use from Grade 6 predictors. In addition, the change scores for each predictor between Grades 6 and 8 (i.e., Grade 8 score minus Grade 6 score) were modeled to predict to the slopes. This allowed for a test of effects of changes in predictors on the slope factors while controlling for the initial predictor values. Paths from all Grade 6 predictors and the alcohol intercepts to each change score were included, and their residual influences were allowed to covary.

Figure 1.

Basic Two-Part Latent Growth Model

(Illustrated for Middle School and Grade 6 Predictors Only)

Prediction to the intercepts of alcohol use and volume were similar for the high school model as for the middle school model. Because of the use of four time points for the high school model (Grades 9 through 12), however, change scores from one assessment period to the next were used to predict alcohol use and volume at Grades 10, 11, and 12. Two of the predictors, antisocial behavior/deviant associations and depressive symptoms, were assessed in all 4 years of high school; thus, change scores from Grades 9 to 10, 10 to 11, and 11 to 12 were calculated as predictors. For parental monitoring, parental alcohol use, and peer alcohol use, change scores from Grade 8 to 10 were used to predict the dependent variables at Grades 10 and 11, and change scores from Grades 10 to 12 were used to predict the dependent variables at Grade 12. This design, although a little complex, made the best use of the multiple assessments to test the hypotheses regarding prediction to growth.

Multiple imputation prior to model estimation was used to estimate the very minimal missing data. Five data sets were imputed using the EM algorithm in NORM (Schafer, 1999), and the IMPUTATION option was used in Mplus to repeat the analyses for each of the data sets and produce parameter estimates that were averaged over the five sets. Standard errors were computed by combining the average of the squared standard errors across the set of analyses and the parameter variation between analyses.

The dependent variables were log transformed to improve computational efficiency during the modeling procedure. In the high school model, because of the number of parameters and the fact that there were no expectations of differential prediction of the time-varying predictors with the alcohol slopes across the high school years, the regression of the individual time points on the time-varying predictors were set to be equal across time. Models were tested using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2006).

4. Results

4.1. Prevalence and Volume of Alcohol Use

Shown in Table 2 are prevalence rates for the prior 12-month period and N by Grade for first alcohol use, any alcohol use, and also average volume of use (untransformed), which included zero use (i.e., nonusers). Just over one half of the sample indicated alcohol use at Grade 6, and the prevalence rate increased over time to 84% by Grade 12. Similarly, the volume of alcohol used increased substantially over time, with large yearly increases from Grades 8 through 11, in particular.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Alcohol Use and Average Volume of Use in the Prior 12 Months by Grade

| Grade | Total N | % N First Use | % N Any Use | Average Volume of use | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 202 | 53 (107) | 53 (107) | 3.29 | 12.41 |

| 7 | 200 | 14 (27) | 49 (98) | 4.54 | 15.04 |

| 8 | 203 | 11 (23) | 58 (117) | 6.54 | 18.37 |

| 9 | 202 | 6 (13) | 63 (127) | 26.60 | 70.34 |

| 10 | 200 | 2 (4) | 66 (131) | 90.23 | 279.97 |

| 11 | 202 | 6 (12) | 79 (159) | 153.10 | 361.41 |

| 12 | 201 | 3 (6) | 84 (169) | 165.27 | 165.27 |

4.2. Two-Part Latent Growth Model of Alcohol Use and Volume in Middle School

Shown in Table 3 is the model predicting to alcohol use and volume through the 3 yearly assessments across the middle school period (ages 11–14 years). In predicting to use versus nonuse (Part I), we found that parental alcohol use and peer alcohol use were associated with a higher likelihood of use at Grade 6 (the intercept). None of the Grade 6 predictors were significantly associated with the slope of use from Grades 6 to 8. Examination of the change score predictors indicated that increases in peer alcohol use from Grades 6 to 8 were associated with higher levels of growth in the likelihood of alcohol use, but change scores in the other predictors were not associated with increased likelihood of use versus nonuse across the period.

Table 3.

Middle School Model

| Intercept | Slope | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Part 1: Use versus nonuse | ||||

| Grade 6 predictors: | ||||

| Parent alcohol use | .94*** | (.22) | −.13 | (.15) |

| Monitoring | .15 | (.24) | −.29 | (.23) |

| Discipline | .11 | (.30) | .17 | (.24) |

| Boys’ antisocial behavior/deviant peer | .34 | (.34) | .34 | (.30) |

| Depressed mood | .05 | (.27) | −.41 t | (.23) |

| Peer alcohol use | .53* | (.25) | .21 | (.27) |

| Change score predictors (Grade 8–Grade 6): | ||||

| Parent alcohol use | .07 | (.20) | ||

| Monitoring | −.32 | (.20) | ||

| Discipline | .19 | (.17) | ||

| Boy’s antisocial behavior/deviant peer | .46 t | (.27) | ||

| Depressed mood | −.23 | (.22) | ||

| Peer alcohol use | .41* | (.20) | ||

|

Part 2: Volume of Use | ||||

| Grade 6 predictors: | ||||

| Parent alcohol use | .16*** | (.04) | −.05* | (.03) |

| Monitoring | −.06 | (.04) | .05 | (.03) |

| Discipline | .02 | (.04) | −.00 | (.03) |

| Boys’ antisocial behavior/deviant peer | .01 | (.04) | .06 | (.05) |

| Depressed mood | .01 | (.04) | −.05 | (.04) |

| Peer alcohol use | .11** | (.04) | .08* | (.03) |

| Change score predictors (Grade 8–Grade 6): | ||||

| Parent alcohol use | .02 | (.03) | ||

| Monitoring | .00 | (.03) | ||

| Discipline | −.01 | (.02) | ||

| Boy’s antisocial behavior/deviant peer | .01 | (.04) | ||

| Depressed mood | −.02 | (.03) | ||

| Peer alcohol use | .10*** | (.03) | ||

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10.

In predicting to volume of alcohol use (Part II, lower panel of Table 3), again both parent and peer alcohol use at Grade 6 were significantly associated with a higher intercept at Grade 6. However, parent alcohol use at Grade 6 was negatively associated with the slope of alcohol volume; likely indicating that because of the initially relatively high levels associated with this predictor there was less-than-average growth across the middle school period. Peer alcohol use was positively associated with the slope of alcohol volume. Prediction from the change scores indicated that increases in peer alcohol use from Grades 6 to 8 were associated with increases in the volume of use in the same periods. Note that none of the paths from the Grade 6 alcohol intercepts to the change scores were significant.

4.3. Two-Part Latent Growth Model of Alcohol Use and Volume in High School

Shown in Table 4 is the model predicting alcohol use and volume across the 4 years of high school (Grades 9–12). The average level of alcohol volume across middle school was included as a control variable and was a significant predictor of the Grade 9 intercept. Findings for prediction to use versus nonuse (Part 1) indicated that the high school use intercept was predicted by the youths’ antisocial behavior and by peer alcohol use. The use slope in high school was negatively predicted by both the use intercept and by peer alcohol use at Grade 9, possibly indicating that because of the relatively high initial use levels associated with these predictors, there was less than average growth in likelihood of use across the period. Prediction from the change scores indicated that increases across time in peer use were associated with a greater likelihood of use versus nonuse.

Table 4.

High School Model

| Intercept | Slope | Time specific | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Part 1: Use versus nonuse | ||||||

| Grade 9 predictors: | ||||||

| Middle school use | 5.23** | (1.65) | .75 | (.64) | ||

| Use intercept | −.23*** | (.06) | ||||

| Parent alcohol use | −.27 | (.42) | .28 t | (.16) | ||

| Monitoring | −.82 t | (.47) | .20 | (.19) | ||

| Discipline | −.13 | (.44) | −.10 | (.14) | ||

| Boys’ antisocial behavior/deviant peer | 1.29* | (.53) | .32 t | (.16) | ||

| Depressed mood | .09 | (.35) | −.15 | (.13) | ||

| Peer alcohol use | 1.61** | (.54) | −.45* | (.21) | ||

| Change score predictors to each time point: | ||||||

| Parent alcohol use | .13 | (.22) | ||||

| Monitoring | .01 | (.28) | ||||

| Boy’s antisocial behavior/deviant peer | .42 t | (.23) | ||||

| Depressed mood | .03 | (.12) | ||||

| Peer alcohol use | 1.03*** | (.25) | ||||

|

Part 2: Volume of use | ||||||

| Middle school use | .51*** | (.13) | −.04 | (.06) | ||

| Volume intercept | −.11 | (.11) | ||||

| Parent alcohol use | .04 | (.05) | .00 | (.02) | ||

| Monitoring | −.08 | (.05) | .01 | (.02) | ||

| Discipline | −.09 t | (.05) | .02 | (.02) | ||

| Boys’ antisocial behavior/deviant peer | .26*** | (.06) | .01 | (.04) | ||

| Depressed mood | −.03 | (.04) | −.05* | (.02) | ||

| Peer alcohol use | .24*** | (.06) | −.02 | (.03) | ||

| Change score predictors: | ||||||

| Parent alcohol use | −.04 | (.03) | ||||

| Monitoring | −.07* | (.03) | ||||

| Boy’s antisocial behavior/deviant peer | .08** | (.03) | ||||

| Depressed mood | .01 | (.02) | ||||

| Peer alcohol use | .10*** | (.03) | ||||

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10.

In predicting to volume of alcohol use in high school given any alcohol use (Part II, lower panel of Table 4), findings indicated that, in addition to average alcohol levels in middle school, the intercept at Grade 9 was predicted by both peer alcohol use and by the boy’s antisocial behavior/deviant associations, also assessed at Grade 9. None of the Grade 9 predictors were significantly associated with the volume slope in a positive direction. Depressed mood was negatively associated with the slope. Regarding the change-score predictors, increases in antisocial behavior/deviant associations and peer alcohol use were associated with increases in volume of use, whereas relative increases in parental monitoring were associated with decreases in the volume of use.

5. Discussion

Findings for prediction to the alcohol outcomes in middle school indicated that the specific effects of parent and peer alcohol use alone were predictive of the intercept of both use and volume of use, and in the presence of these factors, none of the general risk factors for antisocial behavior were significant. Thus, alcohol use by members of the young adolescent’s social network was critical to the initiation of alcohol use. As hypothesized, changes in levels of peer alcohol were associated with the slope of both use and volume of use of alcohol in middle school and, in fact, were the sole positive predictors of the slopes, confirming the importance of this specific social influence on early adolescent alcohol use.

Surprisingly, the intercepts of both use versus nonuse and volume of use in high school (ages 14–15 years) were predicted by the boy’s antisocial behavior/deviant peer associations in addition to peer alcohol use, controlling for middle school use. Taken together with the middle school findings, this would suggest that proximal influences, including the parents own use, have a substantial effect on early use but that antisocial behavior/deviant peer associations become a more critical factor for use later in adolescence. Findings for prediction to growth in volume of use in high school indicated that peer alcohol use was a significant predictor, as were increases in levels of antisocial behavior/deviant peer association. In addition, increases in levels of parental monitoring over time (or possibly maintenance of levels versus decreases) were associated with less growth across the high school years. It has been posited that parental monitoring is mainly driven by adolescent disclosure (Stattin and Kerr, 2000), which certainly is part of the overall monitoring process. In addition to disclosure items (see Table 1), the measures in the current study included items that assessed active parental monitoring and supervision, or the lack of it (e.g., “Your parents let you go any place you please without asking.”). Thus, the findings from the current study provide evidence that active efforts by the parents to supervise their adolescent may limit their growth in alcohol use.

As hypothesized, depressed mood was negatively associated with growth, which replicates the finding by Fleming et al. (2008) for the high school years and is contrary to predictions based on the self-medication hypothesis of a positive association of depressed mood and future alcohol use. Depressed mood is related to poor peer relations or social withdrawal at this age (Capaldi, 1991) and thus may relate to lower levels of associations with deviant peers and exposure to social drinking. However, antisocial behavior/deviant peer association was included in the prediction model, indicating that the effect of depressed mood was not mediated by this construct. It is possible that less socializing with peers overall at adolescence is associated with lower levels of drinking, given the high prevalence of alcohol use among adolescents. Prediction from changes in levels of depressed mood across the high school years did not explain additional variance in growth.

Despite representing a number of advances on prior research, the study has some limitations. First, the sample was predominantly White and included male adolescents only. The extent to which these findings would generalize to other ethnic groups and to girls requires testing. Second, reports of peer alcohol use were limited to reports by the adolescent and did not include assessment of volume of use. Third, although serving size was assessed for the main alcohol categories (beer, wine, and liquor) in an attempt to control for variation in ethanol levels across them, youth may not be very accurate in reporting serving sizes, and there are variations within categories in ethanol levels (e.g., strong versus regular beer). Fourth, the parental discipline measure had relatively low reliability. Fifth, predictors were not assessed every year and, therefore, some of the change score predictors spanned more than 1 year. Finally, the sample size was relatively modest for the models tested, although a strength was the repeated measurements of the dependent variables across the period. In the current study, growth in the middle and high school periods was examined in separate models, partly to address the change in slope of frequency of alcohol use and volume between the two developmental periods. Future work should examine additional approaches to this issue, such as testing transition models (Nylund et al., 2006).

Findings from the current study indicate the importance of alcohol use by parents and peers on the initial levels of use and volume of use in middle school and of peers to growth in use across the middle school and high school periods. This confirms the predictions from the DDS model of the need to examine such specific social influences on problem behaviors (Capaldi et al., 2008) and indicates that limiting the exposure of adolescents to alcohol use by parents and peers is likely both to delay onset and reduce growth in use. As parental monitoring was protective against increased drinking, parents’ efforts to reduce the opportunities for youth to engage in alcohol use with their peers may be the most important prevention strategy at adolescence. The protective effect of parental monitoring may also indicate that interventions emphasizing positive parent-child relationships may also be helpful. The positive associations of antisocial behavior/deviant peer association and volume of use in high school would also indicate that limiting associations and unsupervised time with deviant peers should also have preventive effects. Finally, strategies to prevent growth in antisocial behavior in childhood may also be expected to reduce the risk of any use and in growth of volume of use of alcohol in adolescence. Given the high costs to society of adolescent alcohol use, this indicates the value of further preventive efforts in these directions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jane Wilson, Rhody Hinks, and the data collection staff for their commitment to high quality data, as well as Sally Schwader for editorial assistance with manuscript preparation.

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by NIMH Grant MH 37940 from the Psychosocial Stress and Related Disorders Branch, U.S. PHS. The NIMH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Authors Capaldi and Stoolmiller designed the study and wrote the protocol. Author Capaldi managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work . Authors Stoolmiller and Yoerger undertook the statistical analysis, and author Capaldi wrote the first draft of the manuscript and Stoolmiller, Kim, and Yoeger contributed to further drafts. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for Teacher’s Report Form and 1991 profile. University of Vermont; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and the revised Child Behavior Profile. University of Vermont; Burlington: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Blozis SA, Feldman B, Conger RD. Adolescent alcohol use and adult alcohol disorders: A two-part random-effects model with diagnostic outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S85–S96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EC, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Adolescent substance use outcomes in the raising healthy children project: A two-part latent growth curve analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:699–710. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. The co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: I. Familial factors and general adjustment at Grade 6. Dev Psychopathol. 1991;3:277–300. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Chamberlain P, Fetrow RA, Wilson JE. Conducting ecologically valid prevention research: Recruiting and retaining a “whole village” in multimethod, multiagent studies. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25:471–492. doi: 10.1023/a:1024607605690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Kerr DCR, Owen LD. Intergenerational and partner influences on fathers’ negative discipline. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36:347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9182-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A life span developmental systems perspective on aggression toward a partner. In: Pinsof WM, Lebow J, editors. Family Psychology: The Art of the Science. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M, Clark S, Owen LD. Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Prevalence, prediction, and STD contraction. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:394–406. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pillow DE, Curran PJ, Molina BSG, Barrera M., Jr Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: A test of three mediating mechanisms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;102:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Green KM, Storr CL, Chan YF, Ialongo N, Stuart EA, Anthony JE. Depressed mood in childhood and subsequent alcohol use through adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;633:702–712. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM. Describing Friends Questionnaire. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1985a. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM. Peer Involvement and Social Skills Questionnaire. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1985b. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM, Yoerger K. Middle childhood antecedents to progression in male adolescent substance use: An ecological analysis of risk and protection. J Adolesc Res. 1999;14:175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DW, Patterson GR. Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behav Ther. 1996;27:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Stryker LA. Alcohol use from ages 9 to 16: A cohort-sequential latent growth model. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Mason WA, Mazza JJ, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Latent growth modeling of the relationship between depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:186–197. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz JG, Bray JH. Predicting heavy alcohol use among adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:102–116. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Collins LM, Hill KG, Hawkins JD. Developmental pathways to alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:799–808. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. Piecewise growth mixture modeling of adolescent alcohol use data. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Initiation and course of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults. In: Galanter M, editor. Alcohol Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults: Epidemiology, Neurobiology, Prevention, and Treatment. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 29–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 4. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Muthén BO, Nishina A, Bellmore A, Graham S. Stability and instability of peer victimization during middle school: Using latent transition analysis with covariates, distal outcomes, and modeling extensions. 2006 Web Document, available online at www.statmodel.com.

- Olsen MK, Schafer JL. A two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous longitudinal data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2001;96:730–745. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Social Learning Center. Overt Covert Antisocial Behavior. Eugene: Author; 1984a. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Social Learning Center. Parent Substance Use. Eugene: Author; 1984b. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Bank L. Bootstrapping your way in the nomological thicket. Behav Assess. 1986;8:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. NORM: Multiple Imputation of Incomplete Multivariate Data under a Normal Model [computer software] Penn. State University. Department of Statistics; University Park: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HM, McConnell S. The Walker-McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment. PRO-ED; Austin, TX: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks J, Callan VJ, Austin DA. Parent, peer and personal determinants of adolescent drinking. British J Addiction. 1989;84:619–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]