Abstract

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are used with increasing frequency in neuroengineering applications. CNT scaffolds are used to transmit electrical stimulation to cultured neurons and to control outgrowth and branching patterns of neurites. CNTs have been reported to disrupt normal neuronal function including alterations in endocytotic capability and inhibition of ion channels. Calcium ion channels regulate numerous neuronal and cellular functions including endo and exocytosis, neurite outgrowth, and gene expression. Strong CNT interactions with neuronal calcium ion channels would have profound biological implications. Here we show that physiological solutions containing CNTs inhibit neuronal voltage-gated calcium-ion channels in a dose dependent and CNT-sample-dependent manner with IC50 as low as 1.2 ug/ml. Importantly, we demonstrate that the inhibitory activity does not involve tubular graphene as previously reported, but rather very low concentrations of soluble yttrium released from the nanotube growth catalyst. Cationic yttrium potently inhibits calcium ion channel function with an inhibitory efficacy, IC50, of 0.07 ppm w/w. Because of this potency, unpurified and even some reportedly “purified” CNT samples contain sufficient bioavailable yttrium to inhibit channel function. Our results have important implications for emerging nano-neurotechnology and highlight the critical role that trace components can play in the biological response to complex nanomaterials.

1. Introduction

Carbon nanotubes show promise as scaffolds for neuronal growth[1-4] and stimulation[5-7], nano-pipettes for cell delivery and sampling[8], and electrode coatings for enhanced recording[9]. Keefer and colleagues recently reported that metal wire electrodes can be coated with CNTs to enhance charge transfer, recording, and electrical stimulation of neurons at the brain-machine interface[9]. Intelligent design of this interface may enable the treatment of epilepsy, depression, and Parkinson's disease; and provide hope for restoration of function in paralysis[9,10].

Essential to the success of CNTs in neurotechnologies is their successful integration with electrically active cells. Studies of the patterns of neurites grown upon CNT scaffolds[2,3] have revealed altered neurite outgrowth. Additionally, neurons grown in the presence of water soluble SWNTs demonstrated similar outgrowth patterns to those grown upon CNT scaffolds [4] possibly resulting from interference of stimulated endocytosis from CNTs in the cell external solution[11]. Each of these studies suggests that CNTs alter calcium dependent cellular functions of growing neurons. An earlier study suggests that SWNTs can physically occlude ion channels[12]. The present study was therefore designed to fundamentally assess and characterize the possible effects of CNTs on voltage-gated calcium ion channels, which are present in all excitable cells and underlie many essential cellular functions. In neurons, these channels control calcium entry that triggers transmitter release, gene expression, neuronal excitability, and growth cone extension. Dysfunctional voltage-gated calcium ion channels are implicated in a number of diseases and disorders, and are the targets of many pharmaceutical drugs and neurotransmitters.

2. Materials

2.1 Source, processing, and characterization of SWNTs

A variety of commercial arc-synthesized SWNTs were acquired, characterized, and labeled SWNT A-D. Sample B, C, and D were described by the vendor as “purified” and sample A “as-produced”. Sample C was supplied in functionalized form with 4-6 atom-% carboxylate groups. To obtain uniform suspensions in the electrophysiology buffer, SWNTs were rendered hydrophilic through covalent functionalization with aryl-sulfonate groups. Briefly, SWNTs were immersed in 8.4 mM sulfanilic acid solution at 70°C. While maintaining constant temperature and agitation, 1.5 mL of .2 M sodium nitrite solution was added and allowed to incubate for 2 hours. The SWNTs were subsequently washed with distilled water six times and dried at 100 °C for 8 hours. Aryl-sulfonated SWNTs were then suspended in external solution (see below) through mild bath sonication. Because functionalization may alter metal bioavailability, we performed the bioavailable metal assays (vida infra) after the functionalization step.

Transmission electron microscopy was carried out on JEOL 2010 high-resolution microscope at 200 kV and a Philips 420 microscope at 120 kV. Partial oxidation was carried out to simulate oxidative purification processes for removal of amorphous carbon by heating the carbon nanotubes in a TA Instrument 951 thermogravimetric analyzer at 10 °C/min followed by a 60 min isothermal hold at target temperature. X-ray diffraction analysis of the TGA residues was performed on a Bruker AXS D8 Advance. To remove functional groups on the surface for selected experiments, a ceramic boat was placed in a bench-top tube furnace and purged with nitrogen for 30 min before raising the furnace temperature to 1000°C for 60 min hold time. The furnace was allowed to cool under nitrogen to room temperature.

2.2 Transient expression of CaV2.2 calcium channels in tsA201 cell line

Calcium channel subunits CaV2.2 (AF055477[13]) together with CaVβ3 (sequence homologous to M88751), CaVα2δ1 (AF286488[14]), and enhanced green fluorescent protein cDNAs (eGFP; BD Bioscience) were transiently expressed in tsA201 cells as described previously using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen)[15].

2.3 Cell Studies

Prior to cell exposure, SWNTs were dispersed through 2-hr bath sonication in the identical cell external solution used in the electrophysiology experiments. The solution in the electrophysiology chamber was then replaced with the external solutions containing varying doses of SWNTs. The supernatant sample was generated by transferring the sonicated suspensions to a 5000 NMWL Amicon Ultra-Centrifuge tube (Millipore, MA) and subjecting the samples to centrifugal ultrafiltration at 4500 RPM and 4°C for 30 min. We have shown that this protocol removes essentially all of the nanotubes[16].

2.4 Electrophysiology

Calcium currents were recorded using the standard whole cell patch clamp method as described elsewhere[15]]. The extracellular solution contained 1 mM CaCl2, 4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 135 mM choline chloride, pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The recording electrode solution contained 100 mM CsCl, 10 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM MgATP, pH 7.2 with CsOH. Recording electrodes had resistances of 2-4 MΩ when filled with internal solution. Series resistances (< 6 MΩ for whole cell recording) were compensated 70-80% with a 10 μs lag time. Calcium currents were evoked by voltage-steps and currents leak subtracted on-line using a P/−4 protocol. Data were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz (−3 dB) using pClamp V8.1 software and the Axopatch 200A amplifier (Molecular Devices). All recordings were obtained at room temperature. Cells were typically held at −100 mV to remove closed-state inactivation before applying test pulses 20-25 ms in duration every 6 seconds[15].

2.5 Assays for metal bioavailability assay and cation surface binding

Metal bioavailability (mobilization) assays were performed by dispersing the SWNTs in the identical cell external solution used in the electrophysiology experiments or in lysosomal simulant fluid at pH 5.5 (acetate buffer) and removing the SWNTs through centrifugal ultrafiltration (See Cell Studies). Nickel and yttrium content in the clear filtrate were measured by a Jobin Yvon JY2000 Ultrace inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES) as described previously[16]. Measurements were made at a wavelength of 221.647 nm for Ni and 371.030 nm for Y and intensities were calibrated using standards ranging in concentration from 0 to 5 ug/ml for Ni and from 0 to 10 ug/ml for Y. ICP is accurate at concentrations down to 10 ppb. The interactions between yttrium cation and CNT surface functional groups was studied by adding 0.05-1.0 mg/ml SWNTs to −0.1mM YCl3 aqueous solution (in DI water, saline or acetate buffer) and ultrasonicated in water bath for 1 hr and rotated overnight at 60 rpm. The solids were then removed by centrifugal ultrafiltration and the filtrate analyzed for Y by ICP as above.

3. Results

We used a human embryonic kidney cell line, tsA201, to express cloned neuronal CaV2.2 N-type calcium ion channel chosen for its established role in regulating neurite outgrowth, transmitter release, and neuronal signaling.[17,18] This technique avoids current from other types of channels and thus isolates the behavior of the CaV2.2 N-type calcium ion channel. Calcium currents originating from synchronous activation of CaV2.2 channels were recorded using the whole-cell patch clamp recording method (Fig 1a, and Supplemental). We exposed cells to physiological solutions containing different concentrations of water soluble (aryl-sulfonate functionalized[19]) arc synthesized single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) and monitored the magnitude and voltage-dependence of calcium currents.

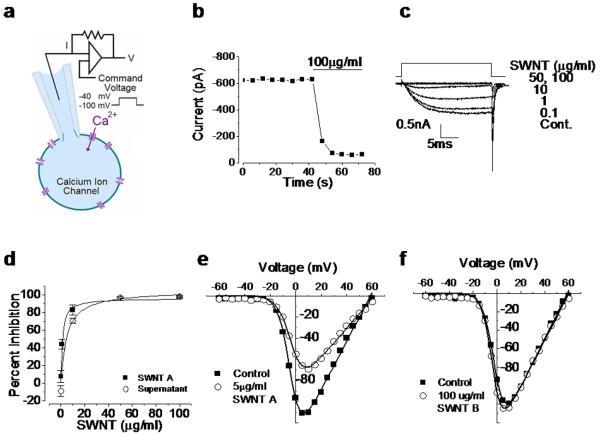

Figure 1.

SWNT sample A inhibits calcium ion channels, while SWNT sample B does not. a: Schematic of whole cell patch clamp experiment. b: Time course of calcium current under constant voltage step exposed to 100 μg/ml SWNT A. Horizontal bar indicates the time of nanotube application. c: Calcium current traces from cell exposed to 0.1, 1, 10, 50 and 100 μg/ml SWNT A. X axis is time in ms and the Y axis is calcium current in mA. d: Dose response of calcium current inhibition resulting from exposure to varying concentrations of SWNT A (solid squares) and associated supernatant (i.e. nanotube-exposed buffer solution after nanotube removal) (open circles). Strong inhibition is seen even in the CNT-free supernatant! Error bars represent standard error (n=3). SWNT A data fit with a hyperbolic non-linear curve, y = 96.3x /(1.22 + x) ; the IC50 of SWNT A is 1.22 μg/ml ± 0.13. The supernatant is fit with hyperbolic non-linear curve y = 105x /(5.0 + x) and the associated IC50 is 5.00 μg/ml ± 2.3. e: Entering calcium current as a function of command voltage over the range −60 mV to 60 mV of control (solid square) and 5 μg/ml SWNT A exposed cell (open circle). The maximum current observed in the control cell occurred at 5 mV and is −111 pA. The maximum current after exposure to 5 μg/ml is at 10 mV and is −69.4 pA. f: Entering calcium current as a function of command voltage over the range −60 mV to 60 mV of control (solid square) and 100 μg/ml SWNT B exposed cell (open circle). Maximum current of −199 pA was observed at 10 mV in control and −125 pA at 5 mV. Panel 1a adapted from Dunlop et al Nature Reviews 2008 [32]

Calcium currents were inhibited rapidly when cells were exposed to SWNT-containing solutions (Fig 1b; sample “A”). Inhibition was dose-dependent (Fig. 1c) and apparent at all voltages without altering the voltage-dependence of channel activation (Fig. 1e). The magnitude and speed of inhibition was unexpected and indicative of direct inhibitory effects on the calcium ion channel (Fig. 1b). We removed the SWNTs from solution through centrifugal ultrafiltration and, surprisingly, observed an almost equivalent level of inhibitory activity (Fig. 1d), which was similar in time course to the action of the original SWNT-containing solution (Fig. 1c). This inhibition occurs in the absence of the original nanotubes.

The inhibitory action of the supernatant indicates a mechanism involving nanotube-induced alteration of the fluid medium, rather than direct interaction between tubular graphene and the ion channel or other cellular targets. High-surface-area SWNTs have been shown to significantly alter cell culture medium through adsorption of folic acid[20] and molecular probes[21] and can release soluble metal forms[16,22,23] through oxidative attack on metal catalyst residues that are not fully encapsulated by graphenic carbon shells[16,24]. To assess the role of metals, we therefore tested the effects of SWNT B, a sample determined to be unusually well purified with respect to free metal (Fig 2 c, d). Physiological solutions containing SWNT B had no detectable inhibitory activity on voltage-gated calcium channels up to 100 μg/ml (Fig. 1f). Since the supernatant of SWNT A had similar inhibitory capability to SWNT A containing solutions, and the unusually well purified sample SWNT B did not have any inhibitory action, this strongly suggests a metals effect rather than an alteration of the buffer composition through adsorption.

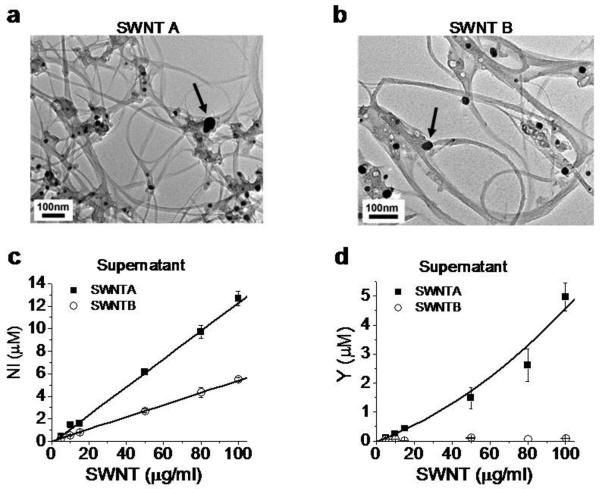

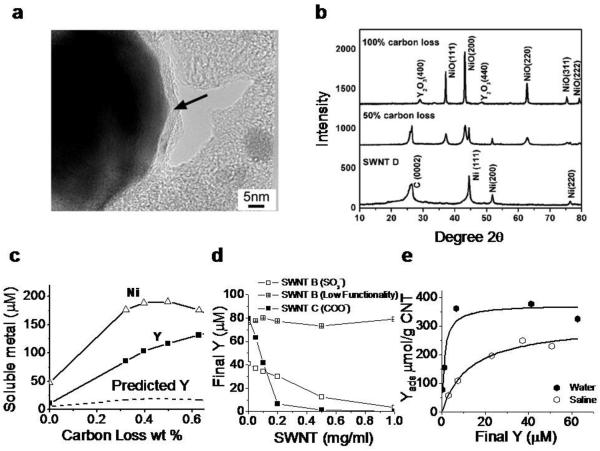

Figure 2.

Bioavailable nickel and yttrium in SWNT samples. a, b: Metal catalyst nanoparticles visible by TEM. Scale bar: 100 nm. Arrows point to catalytic particles. The total metal mass percentages by digestion and ICP-ES are 23.3% nickel and 5.77% yttrium for SWNT A, and 6.7% nickel and 1.3 % yttrium for SWNT B. c,d: Results of quantitative dose-dependent metal mobilization (bioavailability) assays. Figures give total soluble Ni and Y concentrations after SWNT samples were sonicated in CES buffer for 2 hours at pH 7.2 followed by centrifugal ultrafiltration and ICP analysis of the filtrate. These were the same conditions used for electrophysiological characterization. Error bars represent standard deviation from triplicate determination.

The nanotubes in our studies were fabricated using a nickel-yttrium catalyst, and abundant metal nanoparticles are visible in both SWNT samples by TEM (Fig. 2). Previous studies have reported that a small portion of CNT-imbedded metal is typically fluid accessible through defective carbon shells, and can become solubilized in physiological buffers by slow oxidation[16,24]. This “bioavailable” metal fraction is not always eliminated by current purification protocols, and does not correlate well with total metal content[16,24]. As both SWNT samples contain visible metal nanoparticles, we hypothesized that nickel and yttrium are released and solubilized into the recording solution in sufficient quantities to inhibit the channels from SWNT A but not B. We used inductively coupled plasma- atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) to measure levels of bioavailable nickel and yttrium (Figs 2c, 2d) in the recording solution (See Supplemental). Figure 2 shows that both SWNT samples contain bioavailable nickel, but only SWNT A contains detectable quantities of bioavailable yttrium.

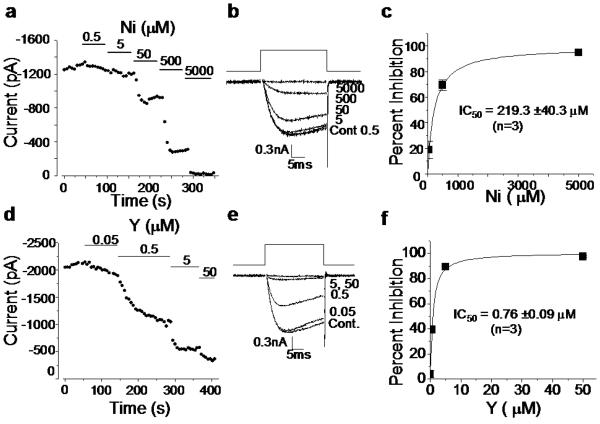

We next tested the sensitivity of N-type calcium channels to nickel and yttrium cations in control salt solutions. Both metals inhibited calcium current rapidly, but yttrium was 300-fold more potent than nickel (Nickel IC50 = 219 ± 40 μM; Yttrium IC50 = 0.76 ± 0.15 μM; n = 3; Fig. 3). Similar inhibitory effects of yttrium have been documented on native calcium channels and calcium-dependent processes[25-27] consistent with inhibitory effects of other ions of the lanthanide series at protein calcium binding sites[25]. Of the trivalent ions in the lanthanide series, yttrium is the most potent inhibitor of high voltage-activated calcium channels[27]. Yttrium like cadmium, another potent inhibitor of high voltage-activated calcium channels, is thought to inhibit calcium flow by competing for calcium binding sites of the ion selectively filter of the pore[26-28] (see Fig. 5). To characterize the factors governing yttrium release from nanotubes, we included two additional SWNT samples (C and D) and studied the location, form, and behavior of CNT-associated yttrium. SWNT C has been commercially functionalized with carboxylate groups. SWNT D was included to show that significant concentrations of bioavailable metal may remain in vendor purified samples. A majority of CNT-associated metal in these samples is in the form of metal-rich nanoparticles encapsulated by thin carbon shells of variable thickness (Fig. 4). Partial oxidation of SWNT D was carried out to simulate oxidative purification processes for removal of amorphous carbon by heating. Air oxidation attacks carbon shell structures (See Supplemental), greatly increasing the mobilization of Y and Ni into media (Fig. 4c). The dissolved Y:Ni ratio is much higher than the initial condensed-phase Y:Ni ratio of 1:7. This indicates preferential oxidation and solution release of Y over Ni, consistent with the higher oxidation potential of Y (2.37 V[29]) relative to Ni (0.25 V). While SWNT D has been “purified” by the supplier, it nevertheless contains sufficient free Y to inhibit channel function, even before air oxidation is employed to remove carbon shells and increase metal bioavailability (~ 10 μM at zero carbon loss in Fig. 4c, which by Fig. 3f, is 13 times the IC50 of Y).

Figure 3.

Control experiments with soluble salts isolate the effects of Ni and Y on neuronal voltage-gated calcium ion channels. a-c: Nickel effects. a: Time course showing decreasing calcium current with increasing nickel dose. Solid bars represent time and dose of application. b: Representative traces of nickel inhibition across the range 0.5 to 5000 μM. c: Nickel dose response curve fit with a hyperbolic non-linear function of the equation: y = 99.3x/(219.3 + x) . From these results, the IC50 for nickel inhibition of CaV2.2-type neuronal calcium channels is 219 μM. d-f: Yttrium effects. d: Time course showing decreasing calcium current with increasing dose of yttrium. Solid bars represent time and dose of application. e: Representative traces of yttrium inhibition across the range 0.05 to 50 μM. f: Yttrium dose response curve fit with a hyperbolic non-linear function of equation: y = 100.7x /(.76 + x) . From these results, the IC50 for yttrium inhibition of CaV2.2-type neuronal calcium channels is 0.76 μM. Yttrium is an extremely potent calcium-ion-channel blocker.

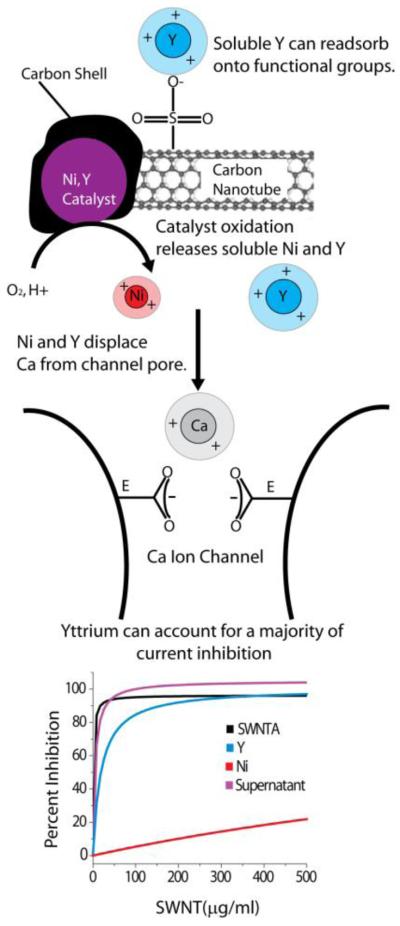

Figure 5.

Summary of proposed mechanism through which carbon nanotube suspensions inhibit neuronal calcium ion channels. Nickel-yttrium catalyst nanoparticles (Purple) are oxidatively corroded by fluid-phase attack through defects or cracks in the surrounding carbon shells leading to solubilization of nickel (Red) and yttrium (Blue) into the media. Purification protocols reduce but do not typically eliminate this bioavailable metal. For functionalized nanotubes, soluble metal can become re-associated during purification or processing by adsorption onto anionic functional groups, to become an additional source of bioavailable metal in nanotube samples[24]. Nickel and especially yttrium ions in solution compete with and displace calcium ions (Gray) from the channel pore. The putative selectivity filter of the calcium ion channel consists of four glutamate residues (E). Two glutamates are shown pointing into the calcium ion pore, creating a calcium ion binding site which is predicted to be part of the ion selectively filter[28]. Calcium is believed to coordinate these residues to enable both high throughput permeability and ion selectivity of the channel. Yttrium cation has a similar ionic radius to calcium, and thus exhibits a good geometric match to the selectivity filter, but is trivalent and has a higher binding coefficient for carboxyl residues than calcium, likely leading to its very high potency as a channel inhibitor. Nickel has a smaller ionic radius than calcium suggesting it is unable to coordinate the carboxyl side chains as effectively as calcium and yttrium consistent with its lower potency as an inhibitor[26]. The figure (bottom) shows model curves generated from our combined data (Figs. 1,2,3) in order to estimate the contribution of yttrium and nickel to the overall inhibition by the whole SWNT A sample. The SWNT A inhibition curve is forecast from our experimental data. The equation of the curve (from Fig. 1d) is SWNT _ Ainh = 96.3x /(1.22 + x) with IC50 1.22 μg/ml SWNT A. Similarly, the equation of the supernatant curve (Fig. 1d) is y = 105x /(5.0 + x) with IC50 of 5.0 μg/ml SWNT A. The concentration of yttrium released from higher doses of SWNT A is given by Yconc = .04[SWNT _ A]. These yttrium concentrations are then substituted into the inhibition curve provided in Fig. 3f. The inhibition associated with each yttrium concentration is shown as a function of corresponding SWNT A concentration to yield the inhibition model shown by equation Yinh = 100.7x /(19.0 + x) with IC50 19.0 μg/ml SWNT A. The concentration of nickel released from higher doses of SWNT A is given by Niconc = .124[SWNT _ A]. These nickel concentrations are then substituted into the inhibition curve provided in Fig. 3c. The inhibition associated with each nickel concentration is shown as a function of corresponding SWNT A concentration to yield the inhibition model shown by equation Niinh = 99.3x /(1768 .5 + x) with IC50 of 1768.5 μg/ml SWNT A. It is evident that yttrium is responsible for a majority of the channel inhibition during nanotube exposure. We find no evidence that the tubular graphene structure is involved in channel inhibition.

Figure 4.

Yttrium phases in SWNTs and mechanisms of yttrium ion release and recapture by SWNT surface functional groups. a: Typical metal catalyst morphology in arc-synthesized SWNT (sample D): Ni/Y nanoparticles are encapsulated in thin (2 – 10 nm) carbon shells (arrow). Previous studies on nanotube nickel and iron show that carbon-shells protect most but not all metal from fluid-phase attack by dioxygen or protons that leads to oxidation and soluble ion release[16,24,33]. b: X-ray diffraction spectra show that most metal is in the form of zero-valent metal nanoparticles with nickel lattice spacing, which upon extensive dry air oxidation can be converted to separate NiO and Y2O3 phases. c: Effect of controlled air oxidation of SWNT D on metal phases and ionic release into a cellular lysosomal simulant buffer at pH 5.5 (2 hr incubation at room temperature of 1.0 mg/ml SWNTs). The dashed curve gives the soluble Y concentration expected if the release were proportional to the Ni release at the initial Ni:Y ratio of 7:1 w/w. SWNT D is marketed as purified and contains a total metal content of 14.3 wt-% Ni and 2.1 wt-% Y by independent analysis. d,e: Fundamental adsorption isotherms that characterize the interactions of soluble yttrium with nanotube surface functional groups. D: sulfonated and carboxylated nantubes remove yttrium ion from solution by surface binding, while the graphenic surfaces of unfunctionalized nanotubes have little effect. e: Adsorption isotherms for yttrium ion binding on SWNT-COOH in pure water and saline. pKa of these COOH groups determined here to be 3.5 by mass titration. Panel E data allow estimation of the fundamental equilibrium constants for competitive Y3+/Na+ binding (see dashed curves and analysis in Supplemental). Kd = 1.2 μM (for Y3+/SWNT-COO−); and Kd = 9060 μM (for Na+/SWNT-COO−).

In samples subjected to acid purification, yttrium salt re-deposition on surface functional groups is also possible and may be an unappreciated source of bioavailable metal in nanotubes. Figure 4d shows that sulfonate and carboxylate functional groups introduced on CNTs can bind soluble yttrium from solution. The adsorption isotherms in panel 4e were used to derive fundamental equilibrium constants for yttrium binding to CNT-carboxylate (See Supplemental) and the competitive effects of Na+ binding on yttrium adsorption from saline solutions. We report dissociation constants: Kd = 1.2 μM (for Y3+/SWNT-COO−); and Kd = 9060 μM (for Na+/SWNT-COO−). The low Kd for soluble Y is consistent with the expected strong binding of the hard Lewis acid Y3+ to the hard carboxylate anion. This strong binding allows significant Y3+ adsorption to occur even in the presence of Na+, which is the major ion in physiological saline (~1500 factor higher concentration than yttrium). The Kd for Ca2+ (Ca2+/SWNT-COO-) is 26.5 μM[24], which is also much higher than Kd for Y3+ (1.2 μM), implying that Y3+ has the potential to replace Ca2+ on carboxylic binding sites.

4. Discussion

Figure 5 summarizes our findings on the chemical pathways for yttrium responsible for SWNT-induced channel inhibition. Included in Fig. 5 is a set of calculated curves derived from the combined data set that give quantitative estimates of the contribution of CNT-derived yttrium and nickel to the overall inhibition seen in the whole nanotube sample. SWNT-derived yttrium can account for the inhibition within experimental error, while nickel is not a factor in this dose range. The modest difference between the whole nanotubes and the yttrium salt solutions may be due to differences in yttrium speciation or cooperative (synergistic) effects of Y and Ni, which were not studied here. The difference cannot reflect a contribution from tubular graphene, because the nanotube-free supernatant shows the same behavior as the whole nanotubes (Fig. 1f) and the nanotube sample with ultra-low-yttrium (B) shows no inhibition (Fig. 1f) even when all the tubular graphene is present.

The potency of yttrium as a channel blocker here is not unexpected, and is likely due to strong yttrium/carboxylate binding, as already discussed for the case of carboxylate groups on nanotube surfaces. The putative selectivity filter within the ion conducting pore of high voltage-gated calcium channels contains four glutamates, one contributed by each of the four domains of the channel[28] (Fig. 5). The carboxyl residues of the glutamate side chains are thought to coordinate two calcium ions; creating the selectively filter and supporting ion permeation[28]. Yttrium is likely to compete for and displace calcium ions from their binding sites within the ion pore without permeating The ionic radii of calcium and yttrium are similar (0.99 and 0.90 Å, respectively) consistent with the proposal that they could occupy the same narrow binding site within the ion pore. Smaller ions like Ni (0.69 Å) have lower affinity perhaps because they cannot coordinate the carboxylate side of the selectivity filter as well as calcium, yttrium, and cadmium. If the trivalent yttrium has a higher binding affinity as compared to calcium, it will occlude calcium entry[25-27]. Unlike calcium, which is present at concentrations high enough to carry charge (2 mM), Y levels are insufficient to support significant current, so the net effect is current inhibition.

Our finding that CNT-yttrium blocks calcium-ion channels has important implications for nanotube-enabled drug delivery, biolabeling, and tissue engineering in bone, muscle, nerve, and other excitable cells. Channel inhibition may also follow unintended nasal inhalation and translocation across the olfactory bulb to the brain[30]. The Ni:Y catalyst is the most common formulation in arc-synthesized SWNTs today[31], and yttrium's high potency on voltage-gated calcium ion channels (IC50 of 70 ppb) suggests SWNTs at levels as low as 1 ug/ml (1 ppm w/w) could disrupt normal calcium signaling in neurons and other electrically active cells.

Our results also indicate that current purification practices do not reliably reduce free yttrium content to levels below 70 ppb, therefore effects on calcium signaling in neurons and other excitable cells may be expected from many arc-synthesized tubes. Tissue engineering applications may be especially sensitive to yttrium released from CNTs because nanotubes are close-packed in scaffolds or on substrates to produce high effective local nanotube concentrations in the near-cellular space. In light of our results, it is possible that soluble metals are the underlying cause of some literature reports of calcium-dependent effects and nanotube-induced ion channel blocking. We note, however, that many studies of nanotube/neuronal interactions use other nanotube types that do not contain yttrium, and thus cannot trigger the mechanism reported here (see for example [7], which uses MWNTs grown using an Fe catalyst). In general, the influence of metal ions in CNT/neuroengineering studies will be highly variable and dependent on the specific nanotube material and its processing history. Future studies should carefully control for the release of metal ions, especially yttrium, to ensure proper interpretation of the observed interaction between nanotubes and electrically active cells.

5. Conclusions

Aqueous suspensions of arc-synthesized single-wall carbon nanotubes are observed here to inhibit neuronal calcium ion channels at low nanotube doses. The electrophysiological characterization of the nanotube-suspensions combined with the control experiments using supernatant solutions and salt solutions clearly show that this inhibition is not due to tubular graphene, the primary nanotube structure, but rather bioavailable yttrium released from the nanotube catalyst. Yttrium is such a potent inhibitor of high voltage-gated calcium ion channels (IC50 of 0.76 uM or 0.07 ppm w/w) that yttrium-related effects on excitable cells are likely to occur for other arc-synthesized SWNT samples. The present finding highlights the complexity of nanomaterial samples and the potential for secondary or trace material features to trigger adverse biological responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful for financial support from the National Institutes of Health (NS29967 and SBRP grant P42 ES013660), the US National Science Foundation (DMI-050661) and the US Environmental Protection Agency (RD-83386201). The technical contributions of Dr. David Murray and Joseph Orchardo are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Seidlits SK, Lee JY, Schmidt CE. Nanostructured scaffolds for neural applications. Nanomedicine. 2008;3(2):183–99. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattson MP, Haddon RC, Rao AM. Molecular Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes and Use as Substrates for Neuronal Growth. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2000;14:175–82. doi: 10.1385/JMN:14:3:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu H, Ni Y, Montana V, Haddon RC, Parpura V. Chemically Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes as Substrates for Neuronal Growth. Nano Letters. 2004;4(3):507–11. doi: 10.1021/nl035193d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ni Y, Hu H, Malarkey EB, Zhao B, Montana V, Haddon RC, et al. Chemically Functionalized Water Soluble Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Modulate Neurite Outgrowth. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 2005;5:1707–12. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2005.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovat V, Pantarotto D, Lagostena L, Cacciari B, Grandolfo M, Righi M, et al. Carbon Nanotube Substrates Boost Neuronal Electrical Signaling. Nano Letters. 2005;5(6):1107–10. doi: 10.1021/nl050637m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzatenta A, Giugliano M, Campidelli S, Gambazzi L, Businaro L, Markram H, et al. Interfacing Neurons with Carbon Nanotubes: Electrical Signal Transfer and Synaptic Stimulation in Cultured Brain Circuits. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;27(26):6931–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1051-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cellot G, Cilia E, Cipollone S, Rancic V, Sucapane A, Giordani S, et al. Carbon Nanotubes might improve neuronal performance by favouring electrical shortcuts. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;4:126–33. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrlau MG, Falls EM, Ziober BL, Bau HH. Carbon nanopipettes for cell probes and intracellular injection. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(015101):1–4. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/01/015101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keefer EW, Botterman BR, Romero MI, Rossi AF, Gross GW. Carbon nanotube coating improves neuronal recordings. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:434–9. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochberg LR, Serruya MD, Friehs GM, Mukand JA, Saleh M, Caplan AH, et al. Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature. 2006;442:164–71. doi: 10.1038/nature04970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malarkey EB, Reyes RC, Zhao B, Haddon RC, Parpura V. Water Soluble Single-walled Carbon Nanotubes Inhibit Stimulated Endocytosis in Neurons. Nano Letters. 2008;8(10):3538–42. doi: 10.1021/nl8017912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park KH, Chhowalla M, Iqbal Z, Sesti F. Single-walled Carbon Nanotubes are a New Class of Ion Channel Blockers. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(50):50212–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Z, Haus S, Edgerton J, Lipscombe D. Identification of Functionally Distinct Isoforms of the N-Type Ca 2+ Channel in Rat Sympathetic Ganglia and Brain. Neuron. 1997;18(1):153–66. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Y, McDonough SI, Lipscombe D. Alternative Splicing in the Voltage-Sensing Region of N-Type Cav2.2 Channels Modulates Channel Kinetics. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92:2820–30. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thaler C, Gray AC, Lipscombe D. Cumulative inactivation of N-type Cav2.2 calcium channels modified by alternative splicing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101(15):5675–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303402101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Gurel V, Morris D, Murray DW, Zhitkovich A, Kane AB, et al. Bioavailability of Nickel in Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Advanced Materials. 2007;(19):2790–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catterall WA, Few AP. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59(6):882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raingo J, Castiglioni AJ, Lipscombe D. Alernative splicing controls G protein-dependent inhibition of N-type calcium channels in nociceptors. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10(3):285–92. doi: 10.1038/nn1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan A, Xiao X, Külaots I, Sheldon BW, Hurt RH. Controlling water contact angle on carbon surfaces from 5° to 167°. Carbon. 2006;44:3113–48. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo L, Von Dem Bussche A, Beuchner M, Yan A, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Adsorption of essential micronutrients by carbon nanotubes and the implications for nanotoxicity testing. Small. 2008;4(6):721–7. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worle-Knirsch JM, Pulskamp K, Krug HF. Oops They Did It Again! Carbon Nanotubes Hoax Scientists in Viability Assays. Nano Letters. 2006;6(6):1261–8. doi: 10.1021/nl060177c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kagan VE, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Konduru NV, Potapovich AI, Osipov AN, et al. Direct and indirect effects of single walled carbon nanotubes on RAW 264.7 macrophages: Role of iron. Toxicology Letters. 2006;165:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulskamp K, Diabaté S, Krug HF. Carbon Nanotubes show no sign of acute toxicity but induce intracellular reactive oxygen species in dependence on contaminants. Toxicology Letters. 2007;168:58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Guo L, Morris D, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Targeted Removal of Bioavailable Metal as a Detoxification Strategy for Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon. 2008;43(3):489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mlinar B, Enyeart JJ. Block of current through T-type calcium channels by trivalent metal cations and nickel in neural rat and human cells. Journal of Physiology. 1992;(469):639–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nachshen DA. Selectivity of the Ca Binding Site in Synaptosome Ca Channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1984;83:941–67. doi: 10.1085/jgp.83.6.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beedle AM, Zamponi G. Inhibition of Transiently Expressed Low- and High- Voltage-Activated Calcium Channels by Trivalent Metal Cations. Journal of Membrane Biology. 2002;(187):225–38. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sather WA, McCleskey EW. Permeation and Selectivity in Calcium Channels. Annual Review of Physiology. 2003;65:133–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horovitz CT. Biochemistry of Scandium and Yttrium, Part 1: physical and chemical fundamentals. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publisher; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oberdörster G, Oberdörster E, Oberdörster J. Nanotoxicology: An Emerging Discipline Evolving from Studies of Ultrafine Particles. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113(7):823–39. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plata DL, Gschwend PM, Reddy CM. Industrially synthesized single-walled carbon nanotubes: compositional data for users, environmental risk assessments, and source apportionment. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:1–13. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/18/185706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunlop J, Bowlby M, Peri R, Vasilyev D, Arias R. High-throughput electrophysiology: an emerging paradigm for ion channel screening and physiology. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008;7:358–68. doi: 10.1038/nrd2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo L, Morris DG, Liu X, Vaslet C, Hurt RH, Kane AB. Iron Bioavailability and Redox Activity in Diverse Carbon Nanotube Samples. Chemistry of Materials. 2007;19(14):3472–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turkel N, Aydin R, Ozer U. Stability of complexes of scandium (III) and yttrium (III) with salicylic acid. Turkish Journal of Chemistry. 1999;23:249–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson DJ, Amm DT, Laureson T, Gupta SK. Monolayers and Langmuir-Blodgett films of yttrium stearate. Thin Solid Films. 1998;326:223–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.