Abstract

Background

Endothelin (ET) and angiotensin mediate glomerular responses to systemic nitric oxide (NO) inhibition. Acute systemic NO synthase (NOS) inhibition in the rat causes marked increases in both preglomerular (RA) and efferent arteriolar (RE) resistances and a fall in the glomerular capillary ultrafiltration coefficient (Kf). In contrast, local intrarenal NOS inhibition increases RA, but has no effect on RE while producing a similar Kf lowering effect as seen with systemic NOS inhibition. These studies were designed to assess whether the increase in RE during systemic NOS inhibition is mediated by endogenous ET and whether angiotensin II (Ang II) also contributes.

Methods

Micropuncture measurements were made before and during acute systemic NOS inhibition with N-monomethyl l-arginine (NMA) alone, NMA + the nonpeptide ETA and ETB receptor antagonist, bosentan, NMA + the Ang II type 1 receptor blocker, losartan, and NMA during combined bosentan and losartan.

Results

The falls in single nephron glomerular filtration rate (SNGFR) and glomerular plasma flow seen with systemic NOS inhibition were prevented by concomitant administration of bosentan and losartan alone and in combination. The increases in systemic blood pressure (BP), glomerular BP (PGC), RA, and RE and the reduction in Kf seen with systemic NOS inhibition were attenuated by either bosentan or losartan. An attenuation in the elevation in total renal vascular resistance seen with systemic NOS inhibition was also observed with bosentan. Combined ET and Ang II type 1 blockade completely prevented the increase in systemic BP, PGC, and RE and the fall in Kf with systemic NOS inhibition, leaving only a very attenuated rise in RA.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that endogenous ET and Ang II partially mediate the glomerular hemodynamic responses (including the increased RE) to acute systemic NOS inhibition. The actions of ET and Ang II are mainly additive, and almost all of the vasoconstrictor responses to acute NOS inhibition are prevented when both vasoconstrictor systems are blocked.

Keywords: vasoconstriction, bosentan, losartan, N-monomethyl l-arginine, efferent arteriolar resistance, single nephron glomerular filtration rate

Nitric oxide (NO) is a potent, physiologically important vasodilator that maintains blood pressure (BP) and renal hemodynamics in the basal state [1–4]. Acute systemic NO synthase (NOS) inhibition in the conscious rat produces a large sustained rise in BP and renal vascular resistance (RVR) [1, 5, 6]. In the anesthetized rat, acute systemic NOS inhibition leads to complex changes in glomerular hemodynamics, with marked increases in both preglomerular (RA) and efferent arteriolar (RE) resistances, such that glomerular BP (PGC) rises significantly [7–9]. In contrast, local intrarenal NOS inhibition has no effect on RE of cortical glomeruli while producing a blunted increase in RA, and because systemic BP remains constant, PGC changes little. A reduction in the glomerular capillary ultrafiltration coefficient (Kf) occurs with both acute systemic and intrarenal NOS inhibition, probably mediated by mesangial cell contraction, because in vitro NO relaxes the glomerular mesangial cells [3, 10, 11]. These observations suggest that the increased RE of cortical glomeruli seen with systemic NOS inhibition is not due to direct inhibition of tonically produced NO in the efferent arteriole, but reflects some secondary phenomenon resulting from systemic NOS inhibition.

The mechanism(s) whereby RE increases during systemic NOS inhibition has not yet been identified. It is possible that a vasoconstrictor system is potentiated or activated during systemic NOS inhibition. There is evidence to suggest participation of both endothelin (ET) and the renin-angiotensin system in the glomerular hemodynamic responses to acute systemic NOS inhibition. For example, acute systemic NOS inhibition potentiates the vasoconstrictor actions of ET [12, 13] and enhances the synthesis and release of ET [14, 15]. In the conscious rat, concomitant ET blockade attenuates the increases in BP and RVR seen with acute systemic NOS inhibition [6]. Angiotensin II (Ang II) contributes to the renal vasoconstrictor response to acute systemic NOS inhibition in situations in which the Ang II system is activated, for example, by acute surgery and/or volume depletion or when circulating Ang II levels are raised by infusion [3, 16, 17].

The aim of these studies was to assess whether endogenous ET and/or Ang II play a role in mediating the glomerular microcirculatory changes during acute systemic NOS inhibition, with particular emphasis on the increased RE. Specifically, we compared the effects on glomerular hemodynamics of acute systemic NOS inhibition during concomitant ET or Ang II blockade, with acute systemic NOS inhibition alone. These studies were conducted in the normal anesthetized, euvolemic (volume restored) rat using micropuncture of the cortical nephrons.

Methods

Studies were conducted on 26 male Sprague-Dawley rats (aged four to five months) obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Rats were housed in laminar flow hoods and were allowed free access to food (approximately 20% protein, approximately 1% NaCl) and drinking water until the day of the experiment. All animal procedures were approved by the West Virginia University Animal Care and Use Committee.

On the day of micropuncture, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of thiobarbiturate, Inactin (120 mg/kg; Research Biochemicals International, Natick, MA, USA). Further supplemental doses (5 to 10 mg/kg) were given intraperitoneally, as required during the experiment. When anesthetized, rats were placed on a temperature-controlled micropuncture table, and the core temperature was maintained at 36 to 38°C. The rat was surgically prepared for glomerular micropuncture studies using the euvolemic (volume restored) preparation [18]. Surgery included a tracheotomy, placement of intravenous lines in the left femoral and both jugular veins for infusion of synthetic plasma, 3H-inulin (approximately 100 to 150 μCi/hr), and drugs and a femoral arterial line to monitor BP and to collect blood samples. The left kidney was exposed through a ventral midline and was left subcostal incision. The left ureter was catheterized. The left renal vein was cannulated, and the left kidney was immobilized and prepared for micropuncture as described previously [19]. The surface of the kidney was illuminated and bathed in warm, 0.9% NaCl solution (34 to 36°C).

After equilibration, control measurements were made as follows: Two exactly timed urine collections (25 to 30 minute) were made. The urine volume was measured, and midpoint blood samples were taken from the femoral artery and renal vein. During the urine collections, the following micropuncture measurements were made in the superficial cortex: Exactly timed (two to three minutes) collections of fluid from four to six superficial proximal tubule segments were taken. Efferent arteriolar blood was collected by puncture of three to five superficial efferent arterioles. Hydrostatic pressures were measured in surface proximal tubules, efferent arterioles, and proximal segments of obstructed tubules (to measure PGC using the indirect stop flow pressure method, as described previously) [20].

At the end of the control measurements, one of the following studies was carried out: Group I [N-monomethyl l-arginine (NMA); N = 6] rats were given an intravenous bolus of the NO synthesis inhibitor NMA (30 mg/kg), followed by a continual intravenous infusion of NMA (2 mg/kg/min). Group II [bosentan (BOS) + NMA; N = 7] received an intravenous bolus of BOS (10 mg/kg, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel Switzerland), the mixed ETA/ETB receptor antagonist. This dose was chosen based on in vivo studies by Clozel et al, in which the initial depressor and sustained pressor response to administered ET-1 was abolished [21]. Ten minutes after the administration of BOS, NMA was given, as in group I. Group III [losartan (LOS) + NMA; N = 8] received an intravenous bolus of the Ang II type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker LOS (3 mg/kg; Du Pont Merck), and 10 minutes later, NMA was given. Group IV (LOS + BOS + NMA) received intravenous LOS followed immediately by intravenous BOS, and 10 minutes later, NMA was given. In all groups, 10 to 15 minutes after the last drug had been administered, two further urine clearances and complete micropuncture measurements were made as described for control.

At the end of all collections in groups II and III, the efficacy of antagonists was confirmed because the dose of BOS prevented both the initial fall and prolonged increase in BP in response to intravenous ET-1 (1 nmol/kg), and LOS completely blocked the pressor response to intravenous Ang II (5 ng).

The activity of 3H-inulin was measured in aliquots of arterial and renal venous plasma, urine, and the entire tubule fluid sample and allowed the calculation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR), renal plasma flow (RPF), and single nephron GFR (SNGFR). Protein concentration of systemic and efferent arteriolar plasma was measured using a microadaptation of the Lowry method [22]. All of these measurements permit calculations of preglomerular (πA) and efferent arteriolar (πE) oncotic pressures, RA and RE, RVR, and Kf. These techniques have been described in detail by us elsewhere [19, 23].

Statistical analyses were by paired t-test within one group and by one-way analysis of variance by the general linear models procedure using SAS [24]. Analysis of variance was done on the percentage change from control to compare the responses with NMA alone (group I) versus BOS + NMA (group II), LOS + NMA (group III), or LOS + BOS + NMA (group IV). Statistical significance was defined as a P of less than 0.05. Data were expressed as mean ± se.

Results

Data for whole kidney and single nephron function in all groups are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. In group I rats receiving NMA alone, BP increased substantially and GFR fell slightly, whereas a more pronounced reduction in RPF occurred because of increased RVR; thus, the filtration fraction (FF) rose. At the single nephron level, acute systemic NOS inhibition caused increases in both RA and RE. As a result, QA decreased, but a large rise in PGC, resulting from the substantial increase in RE, meant that SNGFR fell only slightly. Proximal tubule pressure (PT) is unaffected by acute systemic NOS inhibition, thus the transglomerular hydrostatic pressure gradient (ΔP) increased. Kf was also markedly reduced with acute systemic NOS inhibition. These observations confirm earlier work by us and others [7, 8].

Table 1.

Summary of left kidney and single nephron hemodynamic responses in the normal anesthetized rat

| BP mm Hg |

GRF | RPF | FF | RVR mm Hg/(ml/min) |

SNGFR | QA | PGC | PT | RA | RE | Kf nl/sec/mm Hg |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ml/min | nl/min | mm Hg | 1010dyn × sec × cm−5 | |||||||||

| Group I (NM A; N = 6) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 99±1 | 1.35±0.04 | 3.5±0.1 | 0.39±0.02 | 15±1 | 57±1 | 231±18 | 57±1 | 13±1 | 0.85±0.08 | 0.95±0.08 | 0.042±0.003 |

| +NMA | 131±2 | 1.16±0.06 | 2.3±0.1 | 0.50±0.02 | 29±2 | 44±2 | 120±14 | 79±3 | 14±2 | 1.96±0.30 | 2.87±0.26 | 0.019±0.001 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Group II (BOS + NMA; N = 7) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 101±1 | 1.82±0.06 | 5.1±0.4 | 0.37±0.03 | 11±1 | 67±6 | 220±21 | 62±1 | 14±1 | 0.82±0.08 | 1.17±0.10 | 0.044±0.003 |

| +BOS + NMA | 123±3a | 1.72±0.08 | 3.5±0.2 | 0.49±0.02 | 19±1a | 70±10a | 197±30a | 70±2a | 14±1 | 1.31±0.17a | 1.67±0.21a | 0.037±0.005a |

| P value | <0.001 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.001 | NS | NS | <0.005 | NS | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| Group III (LOS + NMA; N = 8) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 100±1 | 1.52±0.08 | 4.5±0.5 | 0.36±0.02 | 13±1 | 54±3 | 176±15 | 59±2 | 14±1 | 1.06±0.10 | 1.36±0.13 | 0.043±0.003 |

| +LOS +NMA | 125±3a | 1.59±0.16 | 3.3±0.4 | 0.50±0.02 | 22±3 | 56±4a | 153±26a | 73±2a | 14±1 | 1.58±0.20a | 2.23±0.30a | 0.033±0.003a |

| P value | <0.001 | NS | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.005 | NS | NS | <0.001 | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Group IV (LOS + BOS + NMA; N = 5) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 108±3 | 1.17±0.07 | 4.1±0.4 | 0.30±0.02 | 15±2 | 39±2 | 119±11 | 65±2 | 12±1 | 1.66±0.26 | 2.27±0.32 | 0.026±0.002 |

| LOS+BOS + NMA | 111±6 | 1.09±0.10 | 4.1±0.4 | 0.27±0.02 | 15±2 | 40±2 | 113±11 | 60±3 | 11±1 | 2.11±0.31 | 2.37±0.32 | 0.030±0.002 |

| P value | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | <0.05 | NS | NS | <0.05 | NS | NS |

Values are mean ± se. Group I (NMA), acute systemic nitric oxide inhibition with N-monomethyl l-arginine (NMA) alone; Group II (BOS+NMA), combination of both ET blockade with a non-peptide ETA and ETB receptor antagonist bosentan (BOS) and NMA; Group III (LOS + NMA), combination of both angiotensin II inhibition with a selective AT1 receptor blocker losartan (LOS) and NMA; Group IV (LOS+BOS+NMA) combined angiotensin II AT1 and endothelin ETA and ETB receptor antagonism during acute systemic NOS inhibition with NMA. Abbreviations are: BP, mean blood pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; RPF, renal plasma flow; FF, filtration fraction; RVR, renal vascular resistance; SNGFR, single nephron GFR; QA, glomerular plasma flow. PGC, glomerular blood pressure; PT, proximal tubule pressure; RA, preglomerular arteriolar resistance; RE, efferent arteriolar resistance; Kf, glomerular capillary ultrafiltration coefficient; NS, not significant. P values show significant difference by paired t-test.

Significant difference between the change from control to experimental for BOS + NMA (Group II) or LOS + NMA (Group III) versus NMA alone (Group I)

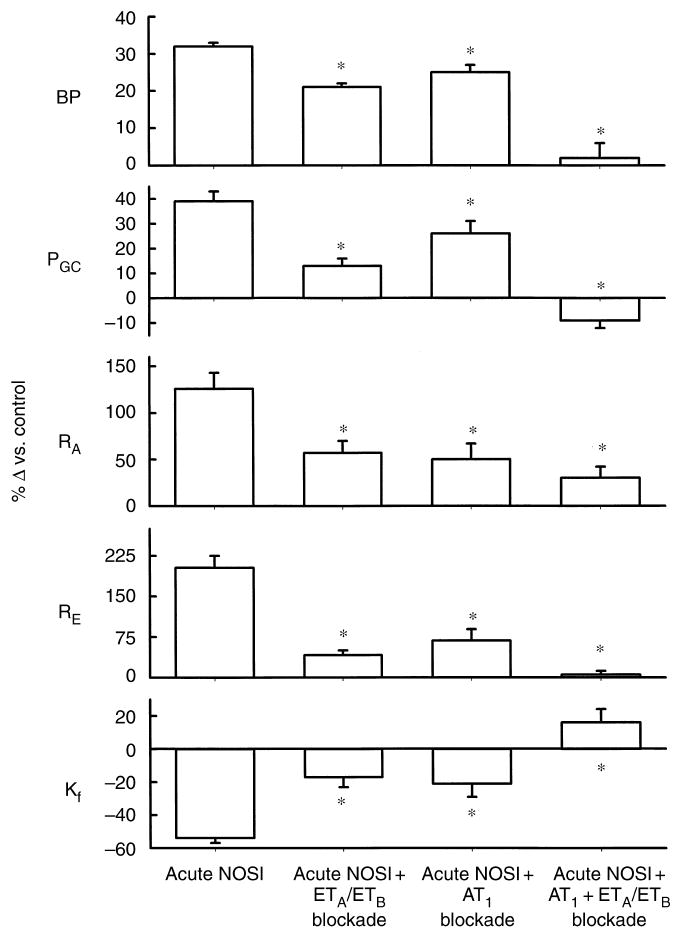

Fig. 1. The percentage change in mean arterial blood pressure (BP), mean glomerular blood pressure (PGC), afferent and efferent arteriolar resistances (RA and RE, respectively), and the glomerular capillary ultrafiltration coefficient (Kf) in the normal anesthetized rat.

Rats received acute systemic NO synthesis inhibition (NOSI) alone, with NMA (group I), combined endothelin blockade of ETA and ETB receptors and NOSI with bosentan and NMA (group II), combined NOSI and angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade with losartan and NMA (group III), and NOSI during combined ETA, ETB, and AT1 receptor blockade (group IV). The asterisk denotes a significant difference in the response versus NOSI alone.

Group II rats received a combination of acute ET blockade with the nonpeptide ETA and ETB receptor antagonist BOS, and acute systemic NOS inhibition with NMA. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, BOS attenuated the increase in BP and RVR and prevented the fall in GFR seen in group I rats receiving NMA alone. In the outer cortical single nephron population, BOS prevented the falls in QA and SNGFR seen with acute systemic NOS inhibition. BOS markedly attenuated the increases in RA and RE and blunted the rise in PGC. BOS also attenuated the fall in Kf seen with NMA alone.

In group III experiments, rats received a combination of acute AT1 blockade with LOS and NMA. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, LOS attenuated the increase in BP and prevented the fall in GFR seen with NMA alone. At the single nephron level, LOS prevented the falls in QA and SNGFR and attenuated the increases in RA, RE, and PGC and the reduction in Kf seen with NMA alone.

Group IV rats received combined AT1 and ETA/B blockade during systemic NOS inhibition with NMA. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, blockade of both AT1 and ET completely prevented the increases in BP, RVR, and FF, as well as the fall in GFR seen in group I rats receiving NMA alone. In outer cortical nephrons, combined LOS and BOS completely prevented the falls in QA, SNGFR, and Kf, as well as the increase in RE and PGC seen with acute systemic NOS inhibition.A markedly attenuated increase in RA persisted.

Discussion

In these studies, we confirmed earlier observations that acute systemic NOS inhibition in the anesthetized, euvolemic rat produced a marked pressor and renal vasoconstrictor response [7–9]. Systemic NOS inhibition caused complex glomerular hemodynamic changes, including reductions in SNGFR and QA, large increases in both RA and RE leading to a marked rise in PGC, and a decline in Kf. However, some of the rise in RA and much of the increased RE in the outer cortical nephrons was indirect (that is, not due to inhibition of intrarenal NOS) because with local intrarenal administration of NOS inhibitor (in which systemic BP did not change), we reported a smaller rise in RA and no increase in RE versus systemic NOS inhibition [7]. The effect on Kf was maintained during local NOS inhibition, suggesting that tonic control of cortical glomerular hemodynamics by NO is confined to the mesangial cell (regulating Kf) and preglomerular resistance vessels (via vascular endothelial and macula densa control) [3, 4, 7, 25]. The exaggerated rise in RA during systemic NOS inhibition probably results from an autoregulatory response to the rise in BP. Most workers conclude that renal autoregulation remains intact during NOS inhibition [3, 4]. However, RE does not participate in normal autoregulatory responses [26], and thus, autoregulation is unlikely to account for the large rise in RE with systemic NOS inhibition.

An alternative explanation is that some underlying vasoconstrictor system is activated and mediates the increase in RE during systemic NOS inhibition. NO is a major endogenous vasodilator that functionally counterbalances active vasoconstrictor systems. Both in vitro and in vivo, acute NOS inhibition potentiates the vasoconstrictor responses to both ET and Ang II [2, 3, 6, 12, 13]. Thus, these studies were designed to investigate the role of endogenous ET and Ang II in mediating the cortical glomerular hemodynamic responses, and particularly the rise in RE, to acute systemic NOS inhibition. It should be noted that although in vivo and in vitro studies have indicated that locally released NO has little role in relaxing the efferent arteriole of superficial nephrons [7, 27], the situation is apparently different in the juxtamedullary population, in which a direct vasodilatory action of NO is seen at both RA and RE [28].

Endothelin is a potent renal vasoconstrictor that increases RA and RE both in vivo and in vitro, although the relative magnitude of these effects varies according to the experimental preparation [11, 27, 29–31]. ET can also contract the mesangial cell and lower Kf when administered in high concentrations [11, 29]. Thus, ET administration mimics the glomerular hemodynamic responses to systemic NOS inhibition. However, acute ET blockade in the normal rat produces a fall in PGC because of an increase in RA [32]. This suggests that endogenous ET tonically dilates, rather than contracts, the preglomerular arteriole via an ETB mediated effect [3, 10, 11], probably secondary to endothelial ETB-stimulated NO and/or prostaglandin production [32].

Acute systemic NOS inhibition not only potentiates the vasoconstrictor actions of ET [12, 13], but also enhances the synthesis and release of ET [14, 15, 33]. In addition, because the tonically active ETB-mediated renal vasodilation is predominantly secondary to NO release in the rat (via endothelial ETB receptors), NOS inhibition unveils the renal vasoconstrictor action of activated ETB receptors on vascular smooth muscles [13, 34, 35]. Furthermore, NO terminates the actions of ET, both by displacing ET from its receptor and by inhibiting the postreceptor response to ET of calcium mobilization [36]. Our previous studies suggested that the pressor and renal vasoconstrictor actions of acute systemic NOS inhibition in the conscious rat are partially mediated by endogenous ET [6]. In the anesthetized rat, ETA-mediated vasoconstriction contributes to the pressor and renal vasoconstrictor actions of acute systemic NOS inhibition [37]. Thus, it is likely that some of the glomerular hemodynamic responses to acute systemic NOS inhibition result from the unrestrained vasoconstrictor actions of ET.

In these studies, we have confirmed our earlier report [6] that concomitant ET blockade attenuates the increases in BP and RVR seen with acute systemic NOS inhibition. At the single nephron level, concomitant ET blockade attenuates the segmental renal vasoconstrictor, glomerular hypertensive, and Kf-lowering effects of systemic NOS inhibition. Of note, the increase in RE caused by NMA was substantially reduced by ET blockade. Thus, the falls in SNGFR and QA with systemic NOS inhibition were prevented by ET blockade. These results suggest that the glomerular microcirculatory changes, including the increased RE during acute systemic NOS inhibition, are partially the result of secondary effects of ET.

Therefore, when renal perfusion pressure (RPP) rises because of NOS inhibition, the kidney exhibits an exaggerated vasoconstriction mediated by ET. In separate studies, we reported that even transient (5 min) exposure of the kidney to a NOS inhibition-induced rise in RPP leads to a prolonged (more than 40 min) renal vasoconstriction [38, 39]. The rise in RVR is not reversible despite normalization of RPP with either vasodilators (NO donor or Ca channel blocker) or by mechanical reduction. Recently, we reported that this “memory” of a transient NOS induced rise in RPP by the kidney is ET mediated, because BOS restores normal renal vascular responses [39]. This prolonged ET-dependent rise in RVR fits well with the extended vasoconstriction action of ET following binding to its vascular receptor [40, 41].

Administered Ang II also produces glomerular hemodynamic responses that closely resemble the response to systemic NOS inhibition [3]. In this study, we found that concomitant Ang II inhibition with LOS also prevents the decreases in SNGFR and QA and attenuates the increases in BP, PGC, RA, and RE, and the reduction in Kf seen with systemic NOS inhibition alone. These findings are consistent with earlier reports [9, 28], which suggests that endogenous Ang II mediates some of the glomerular hemodynamic responses to acute systemic NOS inhibition in the anesthetized animal and in the in vitro juxtamedullary nephron preparation.

These studies therefore show that inhibition of either ET or Ang II will eradicate much of the cortical glomerular hemodynamic responses to systemic NOS inhibition. When both vasoconstrictor systems (ET and Ang II) are blocked simultaneously, the pressor action of acute NOS inhibition is eradicated. The renal vasoconstrictor response is considerably attenuated, with the increase in RE being abolished and only approximately 25% of the increased RA being preserved. Thus, the acute glomerular hypertension seen with NMA is converted to a slight fall in PGC when ET and Ang II are inhibited. These findings implicate a major role for the combined actions of ET and Ang II in mediating the peripheral and renal vasoconstrictor responses to acute systemic NOS inhibition in the anesthetized, euvolemic rat. Only a small fraction of the increased afferent arteriolar tone is apparently mediated by removal of a direct vasodilatory action of NO. Based on the response to combined blockade, most of the vasoconstrictor actions of ET and Ang II are additive, although individual inhibition of the separate vasoconstrictor agonists led to greater than 50% attenuation of the increase in RA and RE. This appears paradoxical; how can each pathway be responsible for the majority of the response? It is now becoming evident, however, that ET and Ang II signal through common intracellular pathways [42], and in fact some of the actions of Ang II can be largely prevented by ET inhibition [43, 44]. Therefore, the glomerular hemodynamic responses (particularly the increase in RE) to acute systemic NOS inhibition are largely mediated by the additive effects of the endogenous ET and Ang II pathways, although there is apparently some overlap between the systems, possibly due to shared intracellular signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant #DK-45517. The excellent technical assistance of Mr. Kevin Engels and Mr. Lennie Samsell are gratefully acknowledged. Bosentan was courteously provided by Dr. Martine Clozel, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. (Basel, Switzerland), and Losartan was provided by Dr. Ronald Smith, Du Pont Merck (Wilmington, DE, USA).

Appendix

Abbreviations used in this article are

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- AT1

angiotensin II type 1

- BOS

bosentan

- BP

blood pressure

- ΔP

hydrostatic pressure gradiant

- ET

endothelin

- FF

filtration fraction

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- Kf

ultrafiltration coefficient

- LOS

losartan

- NMA

N-monomethyl l-arginine

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- πA and πE

preglomerular and efferent arteriolar oncotic pressures

- PGC

glomerular blood pressure

- PT

proximal tubule pressure

- RA

preglomerular arteriolar resistance

- RE

efferent arteriolar resistance

- RPF

renal plasma flow

- RVR

renal vascular resistance

- SNGFR

single nephron glomerular filtration rate

References

- 1.Baylis C, Harton P, Engels K. Endothelial derived relaxing factor (EDRF) controls renal hemodynamics in the normal rat kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1990;1:875–881. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V16875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moncada S, Palmer RMJ, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: Physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raij L, Baylis C. Nitric oxide and the glomerulus. Kidney Int. 1995;48:20–32. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baylis C, Qiu C. Importance of nitric oxide in the control of renal hemodynamics. Kidney Int. 1996;49:1727–1731. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baylis C, Engels K, Samsell L, Harton P. Renal effects of acute endothelial derived relaxing factor blockade are not mediated by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F74–F78. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.1.F74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu C, Engels K, Baylis C. Endothelin modulates the pressor actions of acute systemic nitric oxide blockade. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;6:1476–1481. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V651476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng A, Baylis C. Locally produced EDRF controls preglomerular resistance and ultrafiltration coefficient. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F212–F215. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.2.F212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zata R, De Nucci G. Effects of acute nitric oxide inhibition on rat glomerular microcirculation. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:F360–F363. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.2.F360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Nicola L, Blantz RC, Gabbai FB. Nitric oxide and angiotensin II: Glomerular and tubular interaction in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1248–1256. doi: 10.1172/JCI115709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shultz PJ, Schorer AE, Raij L. Effects of endothelium-derived relaxing factor and nitric oxide on rat mesangial cells. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F162–F167. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.1.F162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badr KF, Murray JJ, Breyer MD, Takahashi K, Inagami T, Harris RC. Mesangial cell, glomerular and renal vascular responses to endothelin in the rat kidney. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:336–342. doi: 10.1172/JCI113880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerman A, Sandok EK, Hildebrand FL, Jr, Burnett JC., Jr Inhibition of endothelium- derived relaxing factor enhances endothelin-mediated vasoconstriction. Circulation. 1992;85:1894–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.5.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richard V, Hogie M, Clozel M, Loffler BM, Thuillez C. In vivo evidence of an endothelin-induced vasopressor tone after inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in rats. Circulation. 1995;91:771–775. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kourembanas S, McQuillan LP, Leung GK, Faller DV. Nitric oxide regulates the expression of vasoconstrictors and growth factors by vascular endothelium under both normoxia and hypoxia. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:99–104. doi: 10.1172/JCI116604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulanger C, Luscher TF. Release of endothelin from porcine aorta: Inhibition by endothelium-derived nitric oxide. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:587–590. doi: 10.1172/JCI114477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigmon DH, Beierwaltes WH. Angiotensin II: Nitric oxide interaction and the distribution of blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R1276–R1283. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.6.R1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baylis C, Harvey J, Engels K. Acute nitric oxide blockade amplifies the renal vasoconstrictor actions of angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;5:211–214. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V52211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichikawa I, Maddox DA, Cogan MC, Brenner BM. Dynamics of glomerular ultrafiltration in euvolemic Munich Wistar rats. Renal Physiol. 1978;1:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baylis C, Deen WM, Myers BD, Brenner BM. Effects of some vasodilator drugs on transcapillary fluids exchange in renal cortex. Am J Physiol. 1976;230:1148–1158. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.4.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baylis C. Immediate and long-term effects of pregnancy on glomerular function in the SHR. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F1140–F1145. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.6.F1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clozel M, Breu V, Gray GA, Kalina B, Loffler BM, Burri K, Cassal JM, Hirth G, Muller M, Neidhart W, Ramuz H. Pharmacological characterization of Bosentan, a new potent orally active non-peptide endothelin receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:228–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munger K, Baylis C. Sex differences in renal hemodynamics in rats. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:F223–F231. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.254.2.F223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT Guide (version 6) Cary: SAS Institute; 1983. pp. 183–260. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito S, Ren Y. Evidence for the role of nitric oxide in macula densa control of glomerular hemodynamics. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1093–1098. doi: 10.1172/JCI116615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navar LG. Renal autoregulation: Perspectives from whole kidney and single nephron studies. Am J Physiol. 1978;234:F357–F370. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1978.234.5.F357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baylis C. Acute interactions between endothelin and nitric oxide in control of renal hemodynamics. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:253–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohishi K, Carmines PK, Inscho EW, Navar LG. EDRF-angiotensin II interactions in rat juxtamedullary afferent and efferent arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:F900–F906. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.5.F900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King AJ, Brenner BM, Anderson S. Endothelin: A potent renal and systemic vasoconstrictor peptide. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:F1051–F1058. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.6.F1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kon V, Yoshioka T, Fogo A, Ichikawa I. Glomerular actions of endothelin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1762–1767. doi: 10.1172/JCI114079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanese DM, Yuan BH, McMurtry IF, Conger JD. Comparative sensitivities of isolated rat renal arterioles to endothelin. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:F894–F899. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.5.F894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiu C, Samsell L, Baylis C. Actions of endogenous endothelin on glomerular hemodynamics in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:R469–R473. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.2.R469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saijonmaa O, Ristimaki A, Fyhrquist F. Atrial natriuretic peptide, nitroglycerine, and nitroprusside reduce basal and stimulated endothelin production from cultured endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:514–520. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verhaar MC, Strachan FE, Newby DE, Cruden NL, Koomans HA, Rabelink TJ, Webb DJ. Endothelin-A receptor antagonist-mediated vasodilatation is attenuated by inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis and by endothelin-B receptor blockade. Circulation. 1998;97:752–756. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuura T, Miura K, Ebara T, Yukimura T, Yamanaka S, Kim S, Iwao H. Renal vascular effects of the selective endothelin receptor antagonists in anaesthetized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:81–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goligorsky MS, Tsukahara H, Magazine H, Anderson TT, Malik AB, Bahou WF. Termination of endothelin signaling: Role of nitric oxide. J Cell Physiol. 1994;158:485–494. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041580313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson A, Valeri CR, Lieberthal W. Endothelin receptor A blockade alters hemodymamic response to nitric oxide inhibition in rats. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H743–H748. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baylis C, Masilamani S, Losonczy G, Samsell L, Harton P, Engels K. Blood pressure (BP) and renal vasoconstrictor responses to acute blockade of nitric oxide: Persistence of renal vasoconstriction despite normalization of BP with either verapamil or sodium nitroprusside. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1135–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang XZ, Baylis C. Endothelin mediates the renal vascular “memory” of a transient rise in perfusion pressure due to acute systemic NOS inhibition. Am J Physiol. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.4.F629. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohan DE. Endothelins in the normal and diseased kidney. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:2–26. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabelink TJ, Kaasjager KAH, Stroes ESG, Koomans HA. Endothelin in renal pathophysiology: From experimental to therapeutic application. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1827–1833. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Heugten HA, Eskildsen-Helmond YE, de Jonge HW, Bezstarosti K, Lamers JM. Phosphoinositide-generated messengers in cardiac signal transduction. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;157:5–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00227875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajagopalan S, Laursen JB, Borthayre A, Kurz S, Keiser J, Haleen S, Giaid A, Harrison DG. Role for endothelin-1 in angiotensin II-mediated hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;30:29–34. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herizi A, Jover B, Bouriquet N, Mimran A. Prevention of the cardiovascular and renal effects of angiotensin II by endothelin blockade. Hypertension. 1998;31:10–14. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]