Abstract

Anthrax lethal toxin (LT) was previously shown to enhance transcriptional activity of NF-κB in tumor necrosis factor-α-activated primary human endothelial cells. Here we show that this LT-mediated increase in NF-κB activation is associated with the enhanced degradation of the inhibitory proteins IκBα and IκBβ but not IκBϵ. Moreover, this was accompanied by enhanced activation of the IκB kinase complex (IKK), which is responsible for targeting IκB proteins for degradation. Importantly, LT enhancement of IκBα degradation was completely blocked by a selective IKKβ inhibitor, whereas IκBβ degradation was attenuated, suggesting a mechanistic link. Consistent with the above data, LT-cotreated cells show elevated phosphorylation of two IKK substrates, IκBα and p65, both of which were blocked by incubation with the IKKβ inhibitor. Consistent with NF-κB activation, LT increased transcription of the NF-κB regulated gene CD40. Conversely, LT inhibited transcription of another NF-κB-regulated gene, CCL2. This inhibition was linked to the LT-mediated suppression of another CCL2-regulating transcription factor, AP-1 (activator protein-1). These data suggest that LT-mediated enhancement of NF-κB is IKK-dependent, but importantly, the net effect of LT on the transcription of proinflammatory genes is driven by the cumulative effect of LT on the particular set of transcription factors that regulate a given promoter. Together, these findings provide new mechanistic insight on how LT may disrupt the host response to anthrax.

Anthrax is a disease caused by the Gram-positive spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Many of the symptoms of systemic anthrax can be attributed to the action of anthrax toxin, which is made up of three secreted proteins, protective antigen (PA),2 and lethal factor (LF), which combine to form lethal toxin (LT), and edema factor (EF), which combines with PA to form edema toxin (1, 2). PA binds to the cell-surface receptors ANTXR1 and ANTXR2, leading to endocytosis of the enzymatic moieties EF and LF (3). Once in the cytosol, EF is a calcium-calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase, causing accumulation of the secondary signaling molecule cAMP (4). LF is a zinc metalloprotease that cleaves proteins of the MEK family, disrupting MAPK signaling (5, 6).

The high mortality resulting from systemic anthrax infection is generally associated with profound vascular pathologies, including vascular leakage, edema, hemorrhage, vasculitis, and a poor immune response (7–9). Importantly, many of these symptoms are also observed in animals treated with purified LT (10–14). In addition, toxin receptor expression appears to be enriched on the endothelium (15). These findings have supported the idea that LT may directly target the endothelium during systemic anthrax infection, when serum levels of LF and PA can exceed 200 and 1000 ng/ml respectively (7, 16–20).

Data from our laboratory further support the hypothesis that vascular endothelium is an important target of LT. We previously reported that LT induces endothelial barrier dysfunction consistent with vascular leakage associated with anthrax (21). In addition, we showed that LT enhances vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression and monocyte adhesion on the surface of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF)-activated primary human endothelial cells, suggesting a possible link between LT and the vasculitis associated with anthrax (9, 22, 23). The enhanced expression of VCAM-1 was found to be transcriptionally driven by the cooperative activation of the VCAM1-regulating transcription factors, interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1), and NF-κB (24). Specifically, LT enhanced nuclear translocation of IRF-1 and NF-κB, which correlated with increased DNA binding of both transcription factors by electromobility shift assay. Considering the critical role of NF-κB in regulating the endothelial inflammatory response, we investigated the mechanisms underlying the enhancement of this pathway by LT.

In this study, we show that LT enhancement of NF-κB correlates temporally with the delayed reaccumulation of the inhibitory molecules IκBα and IκBβ. We also provide evidence that LT enhances activation and phosphorylation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex that is responsible for initiating and maintaining NF-κB activity via phosphorylation of the IκB proteins and the p65 subunit of NF-κB (25–27). In addition to these findings, we tested our previously reported postulate that LT may differentially regulate NF-κB genes in a promoter-dependent manner (24). We show that LT enhances transcription and expression of the surface receptor CD40 but significantly decreases the expression of MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1). The inhibitory effect on this latter gene is driven by LT-mediated inhibition of AP-1 (activator protein-1) activity. Together, these findings provide new mechanistic insight into how LT may alter immune and vascular function and contribute to the poor host response to anthrax infection.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Hanks' balanced salt solutions with calcium and magnesium (HBSS+), and Tris were obtained from Invitrogen. LF and PA were kindly provided by Dr. Stephen H. Leppla (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda) (28, 29). Toxin proteins were diluted in sterile PBS before cell treatment. The proteasome inhibitor MG-132 was purchased from Calbiochem. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma unless noted.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for IκBα and NF-κB (p65) and rabbit monoclonal antibodies specific for IKKβ and the phosphorylated forms of IκBα (Ser(P)-32), p65 (Ser(P)-536), and IKKα/β (recognizes Ser(P)-176/180 of IKKα and Ser(P)-177/181 of IKKβ) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Mouse IgG2a monoclonal antibody specific for CD40, mouse IgG2b monoclonal antibody specific for IκBβ, and rabbit IgG polyclonal antibodies specific for MEKK2, IKKα, IκBβ, IκBϵ, actin, and tubulin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Endothelial Cell Culture and Treatment

Primary human coronary artery endothelial cells were obtained from Cambrex (Walkersville, MD) and cultured as described previously (21). Cells were treated with medium alone (untreated cells), 0.2 ng/ml TNFα, and/or 100 ng/ml LF and 500 ng/ml PA (LT). Consistent with our previous findings, these treatment conditions did not produce any significant changes in monolayer density or cell viability over the course of 24 h (22).

Preparation of Whole Cell, Cytoplasmic, and Nuclear Extracts

Extraction protocols were described in depth previously (24). Protein concentrations were quantitated using the BCA method (Pierce).

Western Blotting

Reduced samples (3–6 μg) were run on NuPAGE 4–12% BisTris gels in MOPS/SDS running buffer. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and detected as described previously (24). Densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells were grown to confluence in 24-well dishes. Immunofluorescence analysis using a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for IκBβ (clone D-8) and an AlexaFluor 555-labeled secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was performed as described previously (14). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342.

IKK Activity Assay

IKK activity in cytoplasmic extracts was analyzed by the ability to phosphorylate exogenous IκBα as described previously (30, 31). Briefly, 0.5 μg of glutathione S-transferase-labeled full-length recombinant IκBα (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was conjugated to 40 μl of 50% glutathione-Sepharose 4B slurry (GE Healthcare) by shaking for 30 min. The beads were washed with PBS and incubated with 40 μg of cytoplasmic extracts for 2 h at room temperature. The beads were then washed with RIPA buffer, resuspended in 2× electrophoresis sample buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and analyzed by Western blot as described above. To confirm the role of IKK, some assays were run using TPCA-1, a selective IKKβ inhibitor (32).

Quantitation of IκBα Phosphorylation

ELISA kits for human IκBα and p-IκBα (Ser(P)-32) were purchased from Invitrogen and performed according to manufacturer's instructions using 3.5–6 μg of whole cell lysates per sample. Samples were analyzed in duplicate; and standards were run with each kit to determine the concentrations of p-IκBα (units/ml) and total IκBα (ng/ml) in each sample. Phosphorylated IκBα was presented as units/mg of protein. Additionally, the relative phosphorylation of IκBα was calculated as units of p-IκBα divided by nanograms of total IκBα.

Serine/Threonine Phosphatase Quantitation

Serine/threonine phosphatase activity was measured using the RediPlate EnzCheck serine/threonine phosphatase assay kit purchased from Invitrogen. Briefly, whole cell lysates were collected in a modified RIPA buffer containing no EDTA, NaF, or sodium orthovanadate. Lysates (4 μg) were analyzed in duplicate and incubated according to the manufacturer's instructions with a combination of tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors and the phosphatase substrate DiFMUP, which is converted to a fluorescent compound when dephosphorylated by cellular serine/threonine phosphatases. The assay was run for 30 min and the fluorescence was measured on a microplate reader with a 360-nm excitation filter and a 465-nm emission filter.

Proteasome Activity Quantitation

Chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity was measured using the Proteasome-Glo cell-based assay purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The assay was run according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were grown in white wall 96-well dishes. Reagent was then added directly to the media that contained cell lysis buffer, the peptide substrate Suc-LLVY-aminoluciferin, and luciferase. Cellular proteasomes cleaved the peptide resulting in a luminescent signal proportional to the amount of proteasome activity in the cells. Luminescence was measured on a microplate reader.

Real Time PCR

RNA extraction and gene expression procedures were described previously (24). Fold gene expression relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (33).

Cell-surface ELISA

Cell-surface ELISA was performed as described previously (21). A primary monoclonal antibody specific for CD40 (1:100) was used for detection. Background values due to detection reagent only were subtracted from the raw data to obtain the final values.

MCP-1 ELISA

Culture supernatants were collected from cells treated as described above and stored at −80 °C. Supernatants were centrifuged to remove debris and diluted (1:100) prior to use. ELISA kit for quantitation of human MCP-1 was purchased from BD Biosciences and performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate.

AP-1 DNA Binding Quantitation

Cells were treated, and extracts were obtained as described above. Binding activity was determined using the AP-1 (c-Jun) TransAM kit purchased from Active Motif. Samples were run in duplicate with 1 μg of nuclear extracts. Briefly, active AP-1 was captured to oligonucleotides containing the consensus binding motif immobilized on a 96-well dish. Bound AP-1 in each sample was then detected using an antibody specific for the phosphorylated form of c-Jun, followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. After addition of detection reagent, the reaction was stopped, and absorbance was read at 450 nm.

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as means ± S.E. for replicate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance with post hoc Student's t test using the JMP (version 5.1) software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

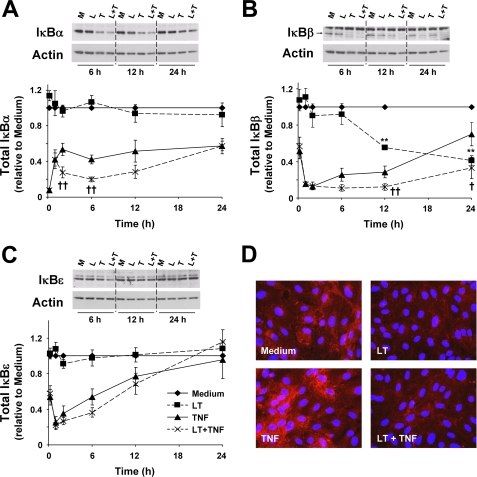

LT Augments Degradation of IκBα and IκBβ but Not IκBϵ

We previously showed that LT inhibits the reaccumulation of IκBα in TNF-treated primary human coronary artery endothelial cells at 6 and 12 h, and we postulated that this contributed to the enhanced NF-κB nuclear translocation and DNA binding observed in cells treated with LT and TNF (LT-cotreated cells) (24). To better understand how LT regulates NF-κB activity, we investigated the effect of LT on IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBϵ at a range of early and late time points. Together these three IκB isoforms regulate the intensity, duration, and the biphasic oscillatory pattern of NF-κB activity during prolonged stimulation (34–36). Of the three proteins, IκBα is degraded the quickest, thus regulating the early phase of NF-κB activity (i.e. <1 h). In cells treated with TNF for 10 min, IκBα is completely degraded (Fig. 1A). Between 10 min and 2 h, IκBα gradually reaccumulates to approximately half of the basal levels, and the expression remains relatively constant throughout the 24-h time course of the experiment. LT alone had no effect of IκBα expression at any time point. With LT-cotreated cells, IκBα levels are equivalent to TNF-treated cells at 10 min and 1 h. However, at 2 and 6 h, IκBα expression is significantly reduced by ∼2-fold in LT-cotreated cells compared with TNF alone. At 12 h, IκBα was also consistently reduced by nearly 2-fold in LT-cotreated cells compared with TNF alone, but this was not statistically significant due to variable expression in TNF-treated cells relative to untreated cells. By 24 h, there was no difference in IκBα expression in the LT-cotreated cells.

FIGURE 1.

LT enhances degradation of IκBα and IκBβ but not IκBϵ. Cells were treated with medium alone or medium containing LT (100 ng/ml LF + 500 ng/ml PA), 0.2 ng/ml TNF, or both. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for expression of IκBα (A), IκBβ (B), and IκBϵ (C) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” At least four blots were performed for each protein at each time point, and representative blots are shown. Graphs represent Western blot densitometry (n ≥4) for medium (diamond, solid line), LT (square, dashed line), TNF (triangle, solid line), and LT + TNF (×, dashed line). Data were normalized relative to cells treated with medium alone and presented as means ± S.E. D, IκBβ immunofluorescence at 24 h. Representative images are shown. M, medium; L, LT; T, TNF; L + T, LT + TNF. **, p < 0.01 versus medium; ††, p < 0.01 versus TNF; †, p < 0.05 versus TNF.

Compared with IκBα, IκBβ is characterized by slower rates of degradation and reaccumulation. Because of this, IκBβ has been reported to regulate the late phase of NF-κB activity in endothelial cells (36). In cells treated with TNF for 10 min, IκBβ expression was about 60% of basal levels (Fig. 1B). Degradation was complete by 1 h, and reaccumulation began at 6 h, with a slow increase to about 70% by 24 h. In LT-cotreated cells, there was no difference in IκBβ expression at 10 min, 1 h, or 2 h as compared with TNF-treated cells. However, at the late time points, IκBβ expression was significantly reduced, with reaccumulation almost completely blocked until a slight increase between 12 and 24 h. In contrast to IκBα, treatment with LT alone produced significant degradation of IκBβ. The degradation was delayed compared with TNF with significant reduction at 12 and 24 h, where expression was about 55 and 40% relative to untreated cells. Reduced IκBβ expression in cells treated with LT alone and in LT-cotreated cells was also observed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 1D).

Degradation of IκBϵ occurs with similar kinetics as IκBβ, whereas reaccumulation tends to be intermediate between IκBα and IκBβ. In cells treated with TNF for 10 min, IκBϵ expression was about 60% of basal levels (Fig. 1C). Degradation was maximal by 1 h, and reaccumulation began at 2 h, with a linear increase to basal levels by 24 h. In LT-cotreated cells, there was no significant difference in IκBϵ expression at any time point compared with TNF alone.

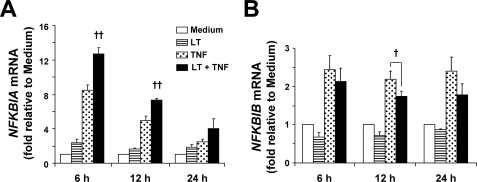

LT Enhances Transcription of NFKBIA and Causes Minor Perturbations in NFKBIB Transcription

To examine whether the effects of LT on IκBα and IκBβ could be explained by reduced transcription of the IκBα and IκBβ-encoding genes NFKBIA and NFKBIB, we analyzed mRNA expression by real time PCR. As shown in Fig. 2A, NFKBIA transcription was induced in TNF-treated cells at 6 and 12 h, and only slightly elevated at 24 h. Cotreatment with LT significantly enhanced transcription compared with TNF alone at 6 and 12 h suggesting the delayed reaccumulation of IκBα in LT-cotreated cells is not caused by inhibition of NFKBIA transcription. Compared with NFKBIA, transcription of the IκBβ-encoding gene NFKBIB was minimally induced in TNF-treated cells (Fig. 2B). LT-treated and LT-cotreated cells showed ∼20–30% reduction in NFKBIB mRNA compared with untreated or TNF-treated cells at 12 h. In addition, we analyzed mRNA stability using actinomycin D as described previously (24), and we found no differences in the stability of NFKBIA or NFKBIB mRNA between TNF-treated and LT-cotreated cells (data not shown). These data suggest that LT-dependent reduction in NFKBIB transcription may contribute to the reduced IκBβ protein expression, whereas the enhanced degradation of IκBα in LT-cotreated cells likely involves a post-transcriptional mechanism.

FIGURE 2.

LT enhances transcription of NFKBIA and causes minor perturbations in NFKBIB transcription. RNA was collected and analyzed for NFKBIA (A) and NFKBIB (B) transcript relative to GAPDH by real time PCR. Means ± S.E. for a minimum of three separate experiments are shown. ††, p < 0.01 versus TNF; †, p < 0.05 versus TNF.

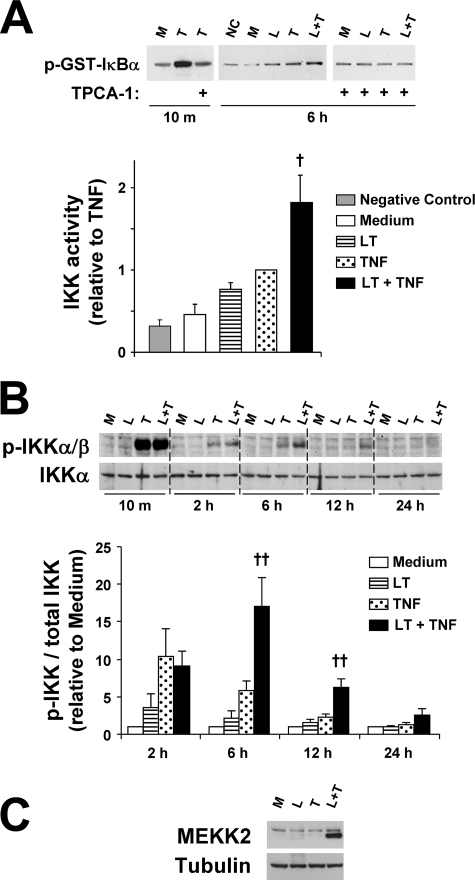

LT Enhances and/or Prolongs TNF-induced IKK Activation

To further examine the mechanism underlying the reduced rate of IκBα and IκBβ reaccumulation, we analyzed the effect of LT on IKK activity using a GST-IκBα assay. Fig. 3A shows that TNF induced maximal IKK activity at 10 min that was blocked when extracts were preincubated with the IKKβ inhibitor TPCA-1. At 6 h, IKK activity was detectable in TNF-treated cells and significantly enhanced by LT cotreatment. LT alone produced a small but consistent increase in IKK activity that did not reach statistical significance. At 12 h, LT induced a 40% increase in IKK activity compared with untreated cells (data not shown, n = 4, p = 0.023). LT cotreatment appeared minimally enhanced but was not statistically significant at 12 h. When extracts were preincubated with TPCA-1, no activity was observed in TNF- or LT-treated or LT-cotreated cells suggesting LT enhancement is dependent upon IKKβ activity (Fig. 3A). Because phosphorylation of IKK (p-IKK) is a prerequisite for its activity, we examined p-IKKα (Ser-176/180)/p-IKKβ (Ser-177/181) by Western blot. IKK phosphorylation was generally minimal under control conditions, and no significant differences were detected with LT alone (Fig. 3B). TNF induced intense p-IKK after 10 min that decreased substantially by 2 h. No differences were noted between TNF-treated and LT-cotreated cells at 10 min or 2 h. At 6 h, p-IKK was still detectable in TNF-treated cells, and phosphorylation was significantly enhanced in LT-cotreated cells. At 12 h, there was no detectable phosphorylation in TNF-treated cells, but phosphorylation was still evident with LT cotreatment. By 24 h, there was no detectable IKK phosphorylation with any treatment. Analysis of the p-IKK Western blots by densitometry suggests that LT cotreatment enhances phosphorylation of IKK by nearly 2.5-fold at 6 and 12 h (Fig. 3B), with no enhancement at 10 min (data not shown), 2 h, or 24 h. These data suggest that LT enhances and/or prolongs IKK activation and phosphorylation in TNF-stimulated cells.

FIGURE 3.

LT cotreatment enhances TNF-induced IKK activity and phosphorylation and MEKK2 expression. A, IKK activity assay was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Where indicated, lysates were incubated for 30 min with TPCA-1 (3 μm) prior to assay. Graph represents Western blot densitometry for three sets of 6-h samples. B, whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for p-IKKα/β and total IKKα levels. At least three blots were performed. Blots are shown for a representative set of 10-min and 2-h samples grouped on one gel and the 6-, 12-, and 24-h samples grouped on a second gel. Graphs represent Western blot densitometry (n ≥3). Data were normalized relative to cells treated with medium alone and presented as means ± S.E. C, whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for expression of MEKK2. A representative blot of four blots is shown. NC, negative control for IKK activity assay (no cell lysates); M, medium; L, LT; T, TNF; L + T, LT + TNF. ††, p < 0.01 versus TNF; †, p < 0.05 versus TNF.

With regard to the mechanism of IKK enhancement, we also tested whether LT enhances p-IKK in response to another pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. As shown in supplemental Fig. 1, LT did in fact enhance IKK phosphorylation in cells cotreated with IL-1β for 3 h. This suggests that the mechanism of IKK enhancement likely occurs downstream of cytokine receptor activation and shares a common link between the TNF receptor and IL-1 receptor pathways.

A number of kinases have been suggested to trigger IKK phosphorylation in response to TNF and IL-1β, including MEKK2 and MEKK3. Of these, MEKK3 has been linked to the initial burst of IKK activity (i.e. <1 h), whereas MEKK2 associates with IKK during the late phase (37, 38). Because LT appears to selectively enhance the late phase, we analyzed whether LT alters MEKK2 expression. MEKK2 was generally expressed at low levels in untreated cells and cells treated with LT or TNF alone, whereas LT-cotreated cells strongly expressed MEKK2 at 6 h (Fig. 3C). Enhanced MEKK2 expression was also occasionally observed in LT-cotreated cells at 12 and 24 h.

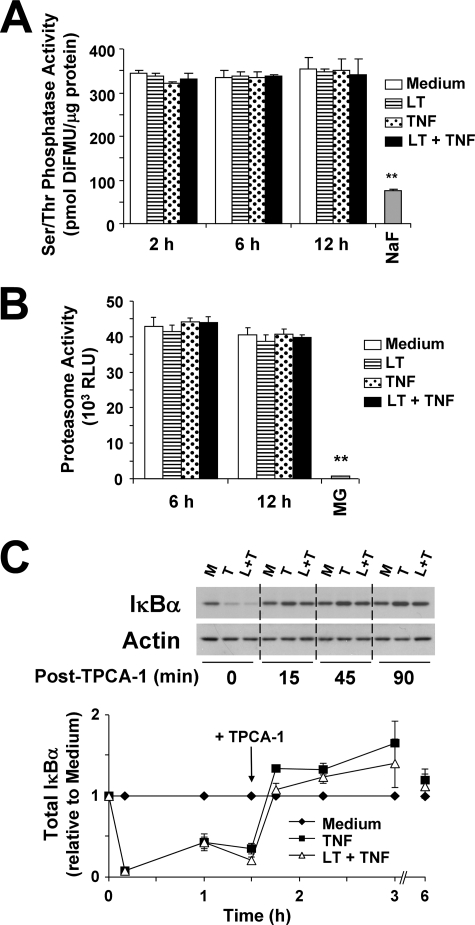

LT Has No Effect on Serine-Threonine Phosphatase Activity, Proteasome Activity, or IκBα Synthesis in the Presence of TPCA-1

In Fig. 1, LT was shown to enhance degradation of IκBα and IκBβ. To strengthen our argument that this is because of the enhanced IKK activity in LT-cotreated cells, we examined whether our observations were because of a generalized reduction in serine-threonine phosphatase activity. As shown in Fig. 4A, LT alone or in cotreatment with TNF had no effect on serine-threonine phosphatase activity at 2, 6, or 12 h. As a negative control, NaF treatment decreased phosphatase activity by 80%. This supports the idea that LT enhancement of IKK phosphorylation and activity is not because of a general inhibition of cellular phosphatase activity.

FIGURE 4.

LT does not alter serine-threonine phosphatase activity, proteasome activity, or IκBα synthesis in the presence of TPCA-1. Cells were treated with medium alone or medium containing LT, TNF, or both. A, whole cell lysates were collected using RIPA buffer containing no phosphatase inhibitors. Phosphatase activity was quantified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” As a negative control, cells treated with medium alone were analyzed in the presence of 50 mm NaF, a pan-serine-threonine phosphatase inhibitor. Data are presented as picomoles of 6,8-difluoro-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin (DiFMU) per μg of protein. Means ± S.E. for three separate experiments are shown. B, cellular chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are presented as relative luciferase units (RLU). As a negative control, cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (MG, 10 μm) for 30 min. Means ± S.E. for four separate experiments are shown. C, cells were treated for 90 min with medium alone, or with TNF, or LT + TNF. Cells were then treated with TPCA-1 (3 μm) to inhibit further IκBα degradation. IκBα accumulation was analyzed by Western blot of whole cell lysates. Representative blot is shown. Graph represents Western blot densitometry (n = 3). **, p < 0.01 versus medium.

Alternatively, the altered degradation and reaccumulation of IκB proteins could be caused by LT enhancement of proteasome activity or inhibition of translational machinery. As shown in Fig. 4B, LT alone or in cotreatment with TNF had no effect on chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity. As a negative control, activity was completely ablated in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG-132. We also analyzed whether LT delay of IκBα reaccumulation was because of inhibition of translational machinery or decreased protein stability independent of IKKβ. In this experiment, cells were treated with LT and TNF to initiate IκBα degradation and NFKBIA transcription. After 90 min, TPCA-1 was added to inhibit further IKKβ activity. Lysates from untreated, TNF-treated, or LT-cotreated cells were then analyzed for IκBα expression to see how quickly the protein would return to basal levels. As shown in Fig. 4C, IκBα levels were equivalently reduced in TNF and LT-cotreated cells at 10 min and 1 h. Just prior to addition of TPCA-1, IκBα was already slightly decreased in LT-cotreated cells compared with TNF alone. However, 15 min after addition of TPCA-1, IκBα expression had returned to basal levels in both TNF- and LT-cotreated cells. In addition, the IκBα levels stayed at or above basal levels through the 6-h time point. These data suggest that LT does not block translation of IκBα, nor does it inherently destabilize the protein, and further suggest the delayed reaccumulation is because of enhanced IKKβ activity.

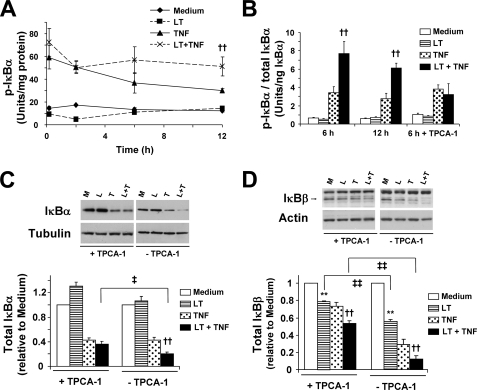

LT Enhances IKKβ-dependent Phosphorylation of IκBα

As discussed above, the major mechanism by which the IKK complex controls NF-κB activity is by phosphorylating the IκB proteins. Phosphorylation of IκBα (at serine residues 32 and 36), IκBβ, and IκBϵ targets each molecule for ubiquitination and proteasome degradation (25, 27, 39). To strengthen our argument that enhancement of IKK activity in LT-cotreated cells is responsible for the delayed reaccumulation of IκBα and IκBβ, we measured IκBα phosphorylation (p-IκBα) by quantitative ELISA, and we examined how pretreatment of cells with TPCA-1 would affect the delay in IκBα and IκBβ reaccumulation. As shown in Fig. 5A, TNF markedly induced p-IκBα after 10 min with slightly decreased levels at 2 h. Consistent with the IKK phosphorylation, no differences were noted between TNF-treated and LT-cotreated cells at these early time points. However, at 6 and 12 h, p-IκBα was markedly decreased in TNF-treated cells, although it remained high in LT-cotreated cells. When we accounted for IκBα degradation by normalizing p-IκBα relative to total IκBα, we found phosphorylation was enhanced by greater than 2-fold in LT-cotreated cells compared with TNF alone at 6 and 12 h (Fig. 5B). When cells were pretreated with TPCA-1, we found no inhibition of the TNF-induced p-IκBα but a complete attenuation of the enhanced levels in LT-cotreated cells (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

LT enhances TNF-induced phosphorylation of IκBα and IκBα and IκBβ degradation. A, quantitation of p-IκBα was performed by ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures” and presented as units of p-IκBα per mg of protein. Means ± S.E. for three separate experiments are shown. B, quantitation of p-IκBα relative to total IκBα was performed by ELISA and presented as units of p-IκBα relative to nanograms of total IκBα. Where indicated, cells were pretreated for 30 min with TPCA-1 (3 μm). Means ± S.E. for three separate experiments are shown. C and D, cells were pretreated for 30 min with TPCA-1 (3 μm). Whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for expression of IκBα (C) and IκBβ (D). Three blots were performed for each protein, and representative blots are shown. Graphs represent Western blot densitometry (n = 3) of total IκBα (C) and total IκBβ (D) in TPCA-1-pretreated cells. Data for samples without TPCA-1 are modified from Fig. 1 and are included here for comparison. M, medium; L, LT; T, TNF; L + T, LT + TNF. **, p < 0.01 versus medium; ††, p < 0.01 versus TNF; ‡‡, p < 0.01 comparing with TPCA-1 versus without TPCA-1; ‡, p < 0.05 comparing with TPCA-1 versus without TPCA-1.

Because IκBα phosphorylation is a signal for proteasomal degradation, we examined whether TPCA-1 could block the LT enhancement of IκBα degradation observed in Fig. 1. Indeed, TPCA-1 completely inhibited the LT enhancement of IκBα degradation compared with cells treated with TNF, suggesting that the reduced IκBα expression is IKKβ-dependent (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the inability of TPCA-1 to block the TNF-induced IκBα degradation agrees with the residual p-IκBα observed in Fig. 5B.

For IκBβ, TPCA-1 partially protected degradation for TNF-treated and LT-cotreated cells, although there was still a significant difference between the two treatments (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, TPCA-1 also afforded significant protection from IκBβ degradation in the cells treated with LT alone, suggesting the degradation in cells treated with LT alone may be partially attributed to the slight enhancement in IKK activity. These data suggest that IKKβ plays an important role in LT enhancement of IκBβ degradation, but unlike for IκBα degradation, there may be other contributing factors, including, for example, the reduced NFKBIB transcription observed in Fig. 2B.

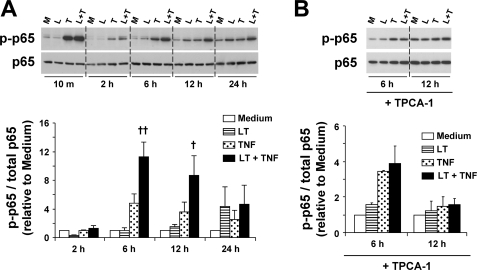

LT Enhances IKKβ-dependent Phosphorylation of p65

Another mechanism by which IKKβ controls NF-κB activity is through phosphorylation of the p65 NF-κB subunit at serine 536, which is thought to enhance transcriptional activity and nuclear localization of NF-κB (25–27, 39). Phosphorylation of p65 was detected at low levels under control conditions or in cells treated with LT alone (Fig. 6A). TNF markedly induced p-p65 after 10 min that declined substantially after 2 h. Again, no differences were noted between TNF-treated and LT-cotreated cells at these early time points. At 6 and 12 h, p-p65 was again elevated in TNF-treated cells. At both time points, densitometry analysis suggests that LT significantly enhances p-p65 by about 2-fold compared with treatment with TNF alone. At 24 h, low level p65 phosphorylation was observed in cells treated with LT alone and TNF alone and appeared slightly enhanced in LT-cotreated cells, but this did not reach the level of statistical significance. When cells were pretreated with TPCA-1, the enhancement in p-p65 at 6 and 12 h was completely blocked in LT-cotreated cells (Fig. 6B). However, we still observed TNF-induced p65 phosphorylation at 6 h, consistent with the data for p-IκBα. Interestingly, the magnitude of enhancement and kinetics of p65 phosphorylation correspond well with the results observed for p-IKK and p-IκBα in LT-cotreated cells. Taken together, these data suggest that LT cotreatment enhances phosphorylation of p65 via an IKKβ-dependent mechanism.

FIGURE 6.

LT enhances TNF-induced phosphorylation of p65. A, whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for p-p65 and total p65 levels. At least three blots were performed. Blots are shown for a representative set of 10-min and 2-h samples grouped on one gel and the 6-, 12-, and 24-h samples grouped on a second gel. Graphs represent Western blot densitometry (n ≥3). Data were normalized relative to cells treated with medium alone and presented as means ± S.E. B, cells were pretreated with TPCA-1 (3 μm) and analyzed for p-p65 and total p65 levels as described above. M, medium; L, LT; T, TNF; L + T, LT + TNF. ††, p < 0.01 versus TNF; †, p < 0.05 versus TNF.

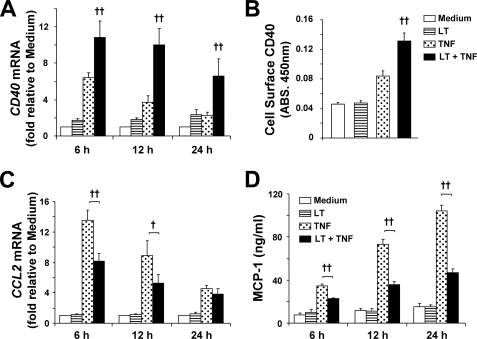

LT Differentially Regulates Transcription of Pro-inflammatory Genes

NF-κB plays a critical role in endothelial pro-inflammatory gene regulation. Having shown that LT enhances activity of the IKK-NF-κB pathway, we wanted to further investigate how LT affects transcription of pro-inflammatory genes. We have shown that LT enhances transcription of several such genes, including VCAM1, IRF1 (24), and NFKBIA (Fig. 2A), the latter being under the transcriptional control of three NF-κB-binding sites (40). To further extend these observations, we chose to investigate the effects of LT on transcriptional regulation of two additional genes with promoters that are regulated by different combinations of transcription factors, CD40 and CCL2.

Transcription of the cell-surface receptor CD40, which belongs to the TNF receptor superfamily, is regulated by NF-κB, signal transducers and activators of transcription-1 (STAT-1), and IRF-1 (41, 42). CD40 transcription was induced in TNF-treated cells at 6 h (Fig. 7A). LT cotreatment significantly enhanced CD40 expression at each time point consistent with our findings that LT enhances the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, STAT-1, and IRF-1 (24). In addition, cell-surface ELISA showed that LT cotreatment enhanced cell-surface expression of CD40 by greater than 50% compared with cells treated with TNF alone (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

LT differentially regulates transcription of NF-κB target genes. A, cells were treated with medium alone or medium containing LT, TNF, or both. RNA was collected and analyzed for CD40 transcript relative to GAPDH by real time PCR. Means ± S.E. for a minimum of three separate experiments are shown. B, cells treated for 24 h as indicated were analyzed by CD40 cell-surface ELISA. Values are reported as means ± S.E. for four separate experiments. C, RNA was collected and analyzed for CCL2 transcript relative to GAPDH by real time PCR. Means ± S.E. for a minimum of three separate experiments are shown. D, MCP-1 release was quantitated by ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Values are reported as means ± S.E. for four separate experiments. ††, p < 0.01 versus TNF; †, p < 0.05 versus TNF.

Expression of CCL2, which encodes for the chemokine MCP-1, is transcriptionally regulated by AP-1 and NF-κB (43, 44). In TNF-treated cells, CCL2 transcription was increased at each time point investigated (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, LT cotreatment significantly reduced transcription of CCL2. Consistent with this finding, MCP-1 secretion, as measured by ELISA, was reduced by more than 30% in LT-cotreated cells at 6 h and by more than 50% at 12 and 24 h (Fig. 7D). Having established that LT enhances NF-κB activity, we hypothesized that LT may be negatively regulating activity of AP-1.

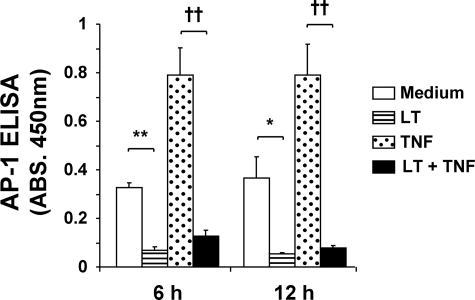

LT Inhibits Basal and Cytokine-induced AP-1 Activity

DNA binding activity of AP-1, a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of c-Fos and c-Jun, was quantified using a trans-binding ELISA (Fig. 8). We observed basal AP-1 activity that was enhanced greater than 2-fold by TNF treatment at 6 and 12 h. Importantly, LT nearly completely inhibited basal and TNF-induced AP-1 activity. This decrease is likely because of the LT-mediated reduction in nuclear c-Jun that we observed previously (24). Together with the previous section, these data demonstrate the dual regulatory action of LT on NF-κB target gene expression and highlight the underlying role of differential regulation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors by LT.

FIGURE 8.

LT inhibits AP-1 DNA binding activity. Cells were treated with medium alone or medium containing LT, TNF, or both. Binding activity of AP-1 was determined by trans-binding ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Means ± S.E. for four separate experiments are shown. **, p < 0.01 versus medium; *, p < 0.05 versus medium; ††, p < 0.01 versus TNF. ABS, absorbance.

DISCUSSION

Vascular pathologies associated with anthrax may be the result of the direct interaction of LT with the endothelium. We have shown in vitro that LT disrupts endothelial barrier function and has both enhancing and suppressive effects on endothelial inflammatory responses (21, 22, 24). The latter is likely to play an important role in the poor immune response and vasculitis associated with anthrax and occurs in part due to enhancement and prolonging of NF-κB activity under varying inflammatory stimuli, including IL-1β and TNFα. The duration and intensity of NF-κB activity are regulated by the degradation and reaccumulation of the inhibitory proteins IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBϵ. In endothelial cells as well as other cell types exposed to prolonged TNF treatment, the differential rates of degradation and reaccumulation of these three proteins account for the two distinct phases or “oscillations” of NF-κB activity (34–36). An early phase, which peaks within the first hour is characterized by the rapid degradation and resynthesis of IκBα. In endothelial cells, the late phase, (i.e. >2 h), has been attributed to the much slower degradation and reaccumulation of IκBβ (36). Importantly, we show that although LT has no effect on IκB expression during time points associated with the early phase, LT cotreatment significantly delayed the reaccumulation of IκBα (at 2 and 6 h) and IκBβ (at 12 and 24 h), but not IκBϵ, during the late phase. The fact that the reduced expression of IκB proteins was most striking at 6 and 12 h suggests a mechanistic link with the enhanced NF-κB activity that was observed at those time points in LT-cotreated cells. Although the reduced IκBβ expression could be partially explained by reduction in gene transcription, LT conversely enhanced transcription of NFKBIA. Importantly, the reduced IκB protein expression in LT-cotreated cells was not because of alterations in proteasome activity or phosphatase activity, and in the case of IκBα, it was not because of impaired translation of NFKBIA mRNA. Together these data suggest the involvement of the IKK complex in the delayed IκB reaccumulation.

The IKK complex, composed of two functionally distinct kinases, IKKα and IKKβ, and the structural subunit IKKγ, is activated in response to a variety of stimuli by phosphorylation as a triggering event in the NF-κB response. Both IKKα and IKKβ have been shown to phosphorylate IκB proteins, targeting them for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity (39, 45, 46). This results in the exposure of a nuclear localization sequence on the p50/p65 heterodimer and leads to nuclear import and subsequent transcription of NF-κB-responsive genes. IKKα and IKKβ have also been shown to phosphorylate p65, resulting in enhanced nuclear localization and transcriptional activity (27, 39, 47). Importantly, we show that LT cotreatment significantly enhanced IKKβ activity and phosphorylation. In addition, we observed phosphorylation of the IKK targets IκBα and p65 that correlated well with the IKK enhancement in terms of magnitude and kinetics. In addition, we showed that inhibition of IKKβ completely blocked the LT enhancement of p65 phosphorylation and IκBα phosphorylation and degradation. The LT-enhanced degradation of IκBβ was partially rescued by the IKKβ inhibitor. Together, these data suggest an active role for IKK in the LT enhancement of NF-κB activation observed in this study and as reported previously (24).

With regard to the mechanism leading to enhanced IKK activation, we provide evidence that LT cotreatment enhances expression of MEKK2, an upstream kinase that has been linked to IKK activation (38, 48). Indeed, MEKK2 is thought to specifically control the late phase of NF-κB activity through assembly of a complex with IKK and IκB proteins (37). The mechanisms underlying LT enhancement of MEKK2 expression are not yet clear, although one hypothesis is that this may represent a feedback response triggered by the LT-mediated cleavage of downstream MEK proteins. Significant attention has focused on LT-mediated MEK cleavage and the resulting downstream inhibition of MAPK signaling; however, to our knowledge, the present findings represent the first demonstration that LT can elicit increased expression of signaling components directly upstream of MEKs. However, it should be noted that MEKK2 expression only appeared enhanced in LT-cotreated cells and was not detectable in cells treated with LT alone. Besides pathways that stimulate IKK, another possibility that warrants further investigation is whether LT may inhibit endogenous endothelial mechanisms that are activated for resolution of the NF-κB response (49). Potential targets include the COX-2 produced cyclopentenone prostaglandins, anti-inflammatory molecules that are exclusively synthesized late in the inflammatory response and have been shown to inhibit IKK activity (50). Other molecules of interest include members of the ovarian tumor (OTU) family of deubiquitinating cysteine proteases that have been shown to be induced by TNF and IL-1 in endothelial cells and are believed to play a role in NF-κB resolution by deubiquitinating receptor-associated signaling intermediaries and inhibition of IKK activity (51).

Until recently, the NF-κB dogma has held that IKKβ and IKKα are functionally distinct kinases with the former being solely responsible for the canonical signaling pathway and the latter controlling the noncanonical pathway. However, it is known that both kinases are capable of phosphorylating IκB proteins, and recently it has been shown that, under certain conditions, IKKα can activate the canonical pathway in numerous cell types, including endothelial cells (47, 52). Indeed, IKKα may be the predominant kinase responsible for IκB degradation in IL-1-treated murine embryonic fibroblast, whereas IKKβ was shown to be generally dispensable (53). Interestingly, the present data show that pretreatment of TNF-treated cells with the selective IKKβ inhibitor TPCA-1 was unable to block p65 phosphorylation or IκBα phosphorylation and degradation at 6 h, a time point associated with the NF-κB late phase (Fig. 5, B and C, and Fig. 6B). This observation is intriguing given that post-treatment with TPCA-1 (90 min after TNF) produced no net IκBα degradation in 6-h TNF-treated cells (Fig. 4C). It is tempting to speculate whether IKKα may compensate for IKKβ in the cells that were pretreated with TPCA-1. Further investigation will be required to address this interesting finding.

Endothelial activation and subsequent gene expression in response to inflammatory stimuli are critical for coordinating the innate immune response to infection (54). The vast majority of inflammatory products produced by endothelium are regulated by the IKK-NF-κB pathway (54–57). In addition, recent studies have shown that abnormal or enhanced activity of the IKK-NF-κB pathway correlates with an unfavorable outcome in many diseases, including heart disease, cancer, and sepsis (58–60). Indeed, IKK inhibitor therapies are currently being developed as a promising treatment for many inflammatory disorders (61). Therefore, the fact that LT alters IKK activity could suggest an important link between LT and certain anthrax-associated pathologies, including vasculitis and the poor immune response. To further investigate the consequences of the enhanced IKK-NF-κB pathway, we examined the effect of LT on the expression of several genes that are regulated by one or varying combinations of inflammatory transcription factors. In the case of the previously discussed NFKBIA, the IκBα-encoding gene regulated solely by NF-κB, LT was shown to enhance mRNA expression. Transcription of NFKBIB, which unlike NFKBIA is only minimally responsive to NF-κB (62), was significantly decreased by LT cotreatment. The expression of CD40, which is regulated by NF-κB, IRF-1, and STAT-1, was likewise increased in LT-cotreated cells. However, transcription of CCL2 was significantly reduced by LT cotreatment and this was likely due to LT inhibition of AP-1. These observations may have pathogenic implications in that LT enhancement of CD40 expression in the presence of CD40L-expressing leukocytes could lead to a synergistic expansion of the inflammatory response through further NF-κB activation and endothelial adhesion molecule expression, suggesting a potential contribution to the vasculitic pathology associated with anthrax (63, 64). In addition, the inhibition of MCP-1 release combined with the reduced expression of the chemokines interleukin-8 and CCL5 may severely alter lymphocyte diapedesis, suggesting an important link between the effect of LT on the endothelium and the poor immune response observed in anthrax (22, 65). Indeed, in vitro studies from our laboratory have shown that, despite enhanced binding of human monocytes and neutrophils (22), LT-cotreated endothelial cells exhibit severe deficiencies in coordinating transmigration compared with cells treated with TNF alone (data not shown).

As mentioned above, the reduction in CCL2 transcription was linked to a dramatic reduction in basal and TNF-induced AP-1 binding activity in LT-treated endothelial cells. This is consistent with previous studies using other cell types and is likely due to the widely reported inhibition of JNK, which stabilizes c-Jun through phosphorylation (24, 66–69). Importantly, the MAPK family regulates other transcription factors involved in immune and inflammatory responses, as well as controlling the activity of additional components of the transcriptional machinery (70). In addition, p38 and JNK have been shown to augment expression of certain genes by enhancing post-transcriptional mRNA stability (71). By disrupting the above MAPK-regulated pathways, LT may influence the expression of many genes in cells exposed to the toxin.

The finding that LT exerts opposing effects on important pro-inflammatory transcription factors appears to lead to an interesting dynamic where pro-inflammatory genes are differentially regulated in LT-cotreated endothelial cells. Whether a particular gene is up- or down-regulated by LT depends on what transcription factors regulate its expression. For example, for some genes, including CD40 and NFKBIA discussed here as well as previously reported VCAM1 and IRF1 (24), the increased NF-κB and IRF-1 activity outweighs the reduction in AP-1 activity and results in enhanced transcription of these genes in LT-cotreated cells. However, for another subset of genes, including CCL2 discussed here and also SELE as reported previously (24), the reduction in AP-1 activity outweighs the increased NF-κB and IRF-1 activity and leads to reduced transcription in LT-cotreated cells.

In conclusion, LT-mediated enhancement of TNF-induced NF-κB activation is because of increased activation of the IKK complex. When combined with the inhibition of AP-1 activity by LT, this leads to potentially important downstream transcriptional up- or down-regulation driven by the cumulative effect of LT on the particular set of transcription factors that control a given promoter. Given the important role of the IKK-NF-κB pathway and AP-1 in immune and inflammatory signaling, the data presented here provide important mechanistic insight into how LT may interact with host cells to cause the characteristic dysregulated immune response and vasculitic pathology observed in anthrax.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. S. H. Leppla for kindly providing the anthrax toxin proteins.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health-Georgetown University Graduate Partnership Program (to J. M. W.) and by the Research Fellowship Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the United States Department of Energy and United States Food and Drug Administration.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- PA

- protective antigen

- EF

- edema factor

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- IL

- interleukin

- IRF-1

- interferon regulatory factor-1

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LF

- lethal factor

- LT

- lethal toxin

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- STAT-1

- signal transducers and activators of transcription-1

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor-α

- VCAM-1

- vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- MEK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- MOPS

- 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moayeri M., Leppla S. H. (2004) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7, 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mourez M. (2004) Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 152, 135–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scobie H. M., Young J. A. (2005) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 106–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leppla S. H. (1982) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 3162–3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turk B. E. (2007) Biochem. J. 402, 405–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duesbery N. S., Webb C. P., Leppla S. H., Gordon V. M., Klimpel K. R., Copeland T. D., Ahn N. G., Oskarsson M. K., Fukasawa K., Paull K. D., Vande Woude G. F. (1998) Science 280, 734–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tournier J. N., Quesnel-Hellmann A., Cleret A., Vidal D. R. (2007) Cell. Microbiol. 9, 555–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guarner J., Jernigan J. A., Shieh W. J., Tatti K., Flannagan L. M., Stephens D. S., Popovic T., Ashford D. A., Perkins B. A., Zaki S. R. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 163, 701–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grinberg L. M., Abramova F. A., Yampolskaya O. V., Walker D. H., Smith J. H. (2001) Mod. Pathol. 14, 482–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Culley N. C., Pinson D. M., Chakrabarty A., Mayo M. S., Levine S. M. (2005) Infect. Immun. 73, 7006–7010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui X., Moayeri M., Li Y., Li X., Haley M., Fitz Y., Correa-Araujo R., Banks S. M., Leppla S. H., Eichacker P. Q. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 286, R699–R709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moayeri M., Haines D., Young H. A., Leppla S. H. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 112, 670–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo S. R., Willingham M. C., Bour S. H., Andreas E. A., Park S. K., Jackson C., Duesbery N. S., Leppla S. H., Tang W. J., Frankel A. E. (2008) Microb. Pathog. 44, 467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolcome R. E., 3rd, Sullivan S. E., Zeller R., Barker A. P., Collier R. J., Chan J. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2439–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshpande A., Hammon R. J., Sanders C. K., Graves S. W. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 4172–4175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh J. J., Pesik N., Quinn C. P., Urdaneta V., Dykewicz C. A., Boyer A. E., Guarner J., Wilkins P., Norville K. J., Barr J. R., Zaki S. R., Patel J. B., Reagan S. P., Pirkle J. L., Treadwell T. A., Messonnier N. R., Rotz L. D., Meyer R. F., Stephens D. S. (2007) Clin. Infect. Dis. 44, 968–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabry R., Brasky K., Geiger R., Carrion R., Jr., Hubbard G. B., Leppla S., Patterson J. L., Georgiou G., Iverson B. L. (2006) Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13, 671–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoop W. L., Xiong Y., Wiltsie J., Woods A., Guo J., Pivnichny J. V., Felcetto T., Michael B. F., Bansal A., Cummings R. T., Cunningham B. R., Friedlander A. M., Douglas C. M., Patel S. B., Wisniewski D., Scapin G., Salowe S. P., Zaller D. M., Chapman K. T., Scolnick E. M., Schmatz D. M., Bartizal K., MacCoss M., Hermes J. D. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7958–7963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyer A. E., Quinn C. P., Woolfitt A. R., Pirkle J. L., McWilliams L. G., Stamey K. L., Bagarozzi D. A., Hart J. C., Jr., Barr J. R. (2007) Anal. Chem. 79, 8463–8470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molin F. D., Fasanella A., Simonato M., Garofolo G., Montecucco C., Tonello F. (2008) Toxicon 52, 824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warfel J. M., Steele A. D., D'Agnillo F. (2005) Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1871–1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steele A. D., Warfel J. M., D'Agnillo F. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337, 1249–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shieh W. J., Guarner J., Paddock C., Greer P., Tatti K., Fischer M., Layton M., Philips M., Bresnitz E., Quinn C. P., Popovic T., Perkins B. A., Zaki S. R. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 163, 1901–1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warfel J. M., D'Agnillo F. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 7516–7524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishore N., Sommers C., Mathialagan S., Guzova J., Yao M., Hauser S., Huynh K., Bonar S., Mielke C., Albee L., Weier R., Graneto M., Hanau C., Perry T., Tripp C. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32861–32871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakurai H., Suzuki S., Kawasaki N., Nakano H., Okazaki T., Chino A., Doi T., Saiki I. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36916–36923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perkins N. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S., Leppla S. H. (2000) Protein Expr. Purif. 18, 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramirez D. M., Leppla S. H., Schneerson R., Shiloach J. (2002) J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28, 232–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta R. A., Polk D. B., Krishna U., Israel D. A., Yan F., DuBois R. N., Peek R. M., Jr. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31059–31066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kupfer R., Scheinman R. I. (2002) J. Immunol. Methods 266, 155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podolin P. L., Callahan J. F., Bolognese B. J., Li Y. H., Carlson K., Davis T. G., Mellor G. W., Evans C., Roshak A. K. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 312, 373–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann A., Levchenko A., Scott M. L., Baltimore D. (2002) Science 298, 1241–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiecker M., Darius H., Liao J. K. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 3316–3322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson D. R., Douglas I., Jahnke A., Ghosh S., Pober J. S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16317–16322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt C., Peng B., Li Z., Sclabas G. M., Fujioka S., Niu J., Schmidt-Supprian M., Evans D. B., Abbruzzese J. L., Chiao P. J. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 1287–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Q., Lee F. S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 8355–8358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Häcker H., Karin M. (2006) Sci. STKE 2006, re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito C. Y., Kazantsev A. G., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 3787–3792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner A. H., Gebauer M., Pollok-Kopp B., Hecker M. (2002) Blood 99, 520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krzesz R., Wagner A. H., Cattaruzza M., Hecker M. (1999) FEBS Lett. 453, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park S. K., Yang W. S., Han N. J., Lee S. K., Ahn H., Lee I. K., Park J. Y., Lee K. U., Lee J. D. (2004) Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 19, 312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin T., Cardarelli P. M., Parry G. C., Felts K. A., Cobb R. R. (1997) Eur. J. Immunol. 27, 1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solt L. A., May M. J. (2008) Immunol. Res. 42, 3–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu C., Ghosh S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31980–31987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luedde T., Heinrichsdorff J., de Lorenzi R., De Vos R., Roskams T., Pasparakis M. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9733–9738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winsauer G., Resch U., Hofer-Warbinek R., Schichl Y. M., de Martin R. (2008) Cell. Signal. 20, 2107–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winsauer G., de Martin R. (2007) Thromb. Haemost. 97, 364–369 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossi A., Kapahi P., Natoli G., Takahashi T., Chen Y., Karin M., Santoro M. G. (2000) Nature 403, 103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Enesa K., Zakkar M., Chaudhury H., Luong le, A., Rawlinson L., Mason J. C., Haskard D. O., Dean J. L., Evans P. C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7036–7045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeBusk L. M., Massion P. P., Lin P. C. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 10223–10228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solt L. A., Madge L. A., Orange J. S., May M. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 8724–8733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pober J. S., Sessa W. C. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 803–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viemann D., Goebeler M., Schmid S., Klimmek K., Sorg C., Ludwig S., Roth J. (2004) Blood 103, 3365–3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denk A., Goebeler M., Schmid S., Berberich I., Ritz O., Lindemann D., Ludwig S., Wirth T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28451–28458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collins T., Read M. A., Neish A. S., Whitley M. Z., Thanos D., Maniatis T. (1995) FASEB J. 9, 899–909 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moss N. C., Stansfield W. E., Willis M. S., Tang R. H., Selzman C. H. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H2248–H2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karin M. (2006) Nature 441, 431–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu S. F., Malik A. B. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 290, L622–L645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strnad J., Burke J. R. (2007) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Budde L. M., Wu C., Tilman C., Douglas I., Ghosh S. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4179–4194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chakrabarti S., Blair P., Freedman J. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18307–18317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Henn V., Slupsky J. R., Gräfe M., Anagnostopoulos I., Förster R., Müller-Berghaus G., Kroczek R. A. (1998) Nature 391, 591–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Batty S., Chow E. M., Kassam A., Der S. D., Mogridge J. (2006) Cell. Microbiol. 8, 130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Musti A. M., Treier M., Bohmann D. (1997) Science 275, 400–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fang H., Cordoba-Rodriguez R., Lankford C. S., Frucht D. M. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 4966–4971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paccani S. R., Tonello F., Ghittoni R., Natale M., Muraro L., D'Elios M. M., Tang W. J., Montecucco C., Baldari C. T. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 325–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kang Z., Webster Marketon J. I., Johnson A., Sternberg E. M. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 389, 595–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Turjanski A. G., Vaqué J. P., Gutkind J. S. (2007) Oncogene 26, 3240–3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eberhardt W., Doller A., Akool el-S., Pfeilschifter J. (2007) Pharmacol. Ther. 114, 56–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.